Submitted:

04 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

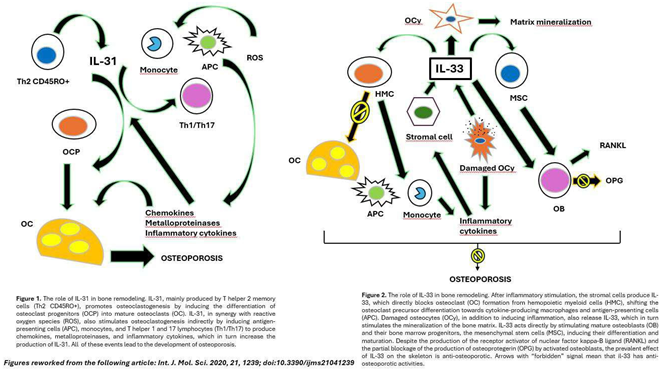

Osteoporosis and the IL-31/33 Axis

Overview of OCS Available and Conversion of Doses of OCS

| CORTICOSTEROIDS (OCS) |

APPROXIMATE EQUIVALENT DOSE (MILLIGRAMS) |

|---|---|

| Cortisone | 25 mg |

| Hydrocortisone | 20mg |

| Deflazacort | 7,5mg |

| Prednisolone | 5mg |

| Prednisone | 5mg |

| Methylprednisolone | 4mg |

| Triamcinolone | 4mg |

| Betamethasone | 0,75mg |

| Dexamethasone | 0,75mg |

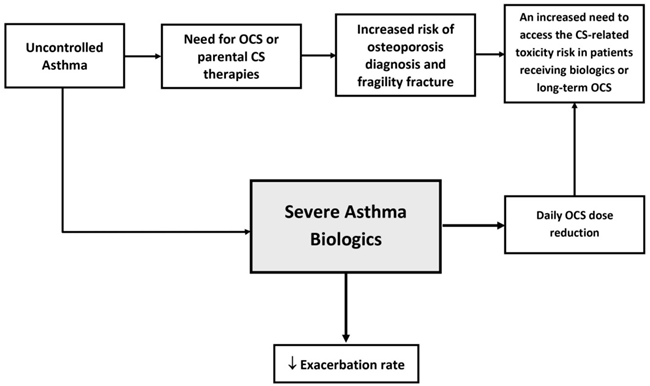

The Impact of Severe Asthma Biologics in Sparing Steroid Therapy

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2024. Update May 2024. Available online: http://www.ginasthma.org/.

- Kearney, D.M.; Lockey, R.F. Osteoporosis and asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006, 96, 769–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalitsios, C.V.; Shaw, D.E.; McKeever, T.M. Corticosteroids and bone health in people with asthma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2021, 181, 106374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalitsios, C.V.; McKeever, T.M.; Shaw, D.E. Incidence of osteoporosis and fragility fractures in asthma: a UK population-based matched cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2021, 57, 2001251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heffler, E.; Madeira, L.N.G.; Ferrando, M.; Puggioni, F.; Racca, F.; Malvezzi, L.; Passalacqua, G.; Canonica, G.W. Inhaled Corticosteroids Safety and Adverse Effects in Patients with Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018, 6, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.J.; Phillips, P.J.; Heller, R.F. Asthma and chronic obstructive airway diseases are associated with osteoporosis and fractures: a literature review. Respirology. 1999, 4, 101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalitsios, C.V.; Shaw, D.E.; McKeever, T.M. Risk of osteoporosis and fragility fractures in asthma due to oral and inhaled corticosteroids: two population-based nested case-control studies. Thorax. 2021, 76, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardet, J.C.; Bulkhi, A.A.; Lockey, R.F. Nonrespiratory Comorbidities in Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021, 9, 3887–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weare-Regales, N.; Hudey, S.N.; Lockey, R.F. Practical Guidance for Prevention and Management of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis for the Allergist/Immunologist. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021, 9, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpaij, O.A.; van den Berge, M. The asthma-obesity relationship: underlying mechanisms and treatment implications. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018, 24, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslan, J.; Mims, J.W. What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and health care costs. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014, 47, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Barcala, F.J.; Muñoz-Gall, X.; Mariscal, E.; García, A.; Yang, S.; van de Wetering, G.; Izquierdo-Alonso, J.L. Cost-effectiveness analysis of anti-IL-5 therapies of severe eosinophilic asthma in Spain. J Med Econ. 2021, 24, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virchow, J.C.; Barnes, P.J. Asthma. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012, 33, 577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of asthma and COPD. Clin Sci (Lond). 2017, 131, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J.; Adcock, I.M. How do corticosteroids work in asthma? Ann Intern Med. 2003, 139, 359–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginaldi, L.; De Martinis, M.; Ciccarelli, F.; Saitta, S.; Imbesi, S.; Mannucci, C.; Gangemi, S. Increased levels of interleukin 31 (IL-31) in osteoporosis. BMC Immunol. 2015, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Martinis, M.; Sirufo, M.M.; Suppa, M.; Ginaldi, L. IL-33/IL-31 Axis in Osteoporosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirufo, M.M.; Suppa, M.; Ginaldi, L.; De Martinis, M. Does Allergy Break Bones? Osteoporosis and Its Connection to Allergy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malerba, M.; Romanelli, G.; Grassi, V. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in asthma and respiratory diseases. Front Horm Res. 2002, 30, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J. Pathophysiology of asthma. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996, 42, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.J.; Phillips, P.J.; Heller, R.F. Asthma and chronic obstructive airway diseases are associated with osteoporosis and fractures: a literature review. Respirology. 1999, 4, 101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.F.; Barnes, P.J. Role of inflammatory mediators in asthma. Br Med Bull. 1992, 48, 135–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parente, L. Deflazacort therapeutic index, relative potency and equivalent doses versus other corticosteroids, BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2017, 18,1.

- RCP Cortisone.

- RCP Hydrocortisone.

- RCP Deflazacort.

- RCP Prednisolone.

- RCP Prednisone.

- RCP Methylprednisolone.

- RCP Triamcinolone.

- RCP Betamethasone.

- RCP Dexamethasone.

- Chung, K.F.; Wenzel, S.E.; Brozek, J.L.; Bush, A.; Castro, M.; Sterk, P.J.; Adcock, I.M.; Bateman, E.D.; Bel, E.H.; Bleecker, E.R.; et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014, 43, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, K.F.; Wenzel, S.E.; Brozek, J.L.; Bush, A.; Castro, M.; Sterk, P.J.; Adcock, I.M.; Bateman, E.D.; Bel, E.H.; Bleecker, E.R.; et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014, 43, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Difficult-to-treat and severe asthma in adolescent and adult patients. 2019. Available online: https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/GINA-Severe-asthma-Pocket-Guide-v2.0-wms-1.pdf.

- Price, D.B.; Trudo, F.; Voorham, J.; Xu, X.; Kerkhof, M.; Ling, Zhi Jie, J.; Tran, T.N. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy. 2018, 11, 193–204. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahy, J.V. Type 2 inflammation in asthma—present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015, 15, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambrecht, B.N.; Hammad, H.; Fahy, J.V. The cytokines of asthma. Immunity. 2019, 50, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teach, S.J.; Gill, M.A.; Togias, A.; Sorkness, C.A.; Arbes, S.J. Jr.; Calatroni, A.; Wildfire, J.J.; Gergen, P.J.; Cohen, R.T.; Pongracic, J.A.; et al. Preseasonal treatment with either omalizumab or an inhaled corticosteroid boost to prevent fall asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015, 136, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, M.; Kozawa, M.; Yoshisue, H.; Milligan, K.L.; Nagasaki, M.; Sasajima, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Ohta, K. Real-world safety and efficacy of omalizumab in patients with severe allergic asthma: a long-term post-marketing study in Japan. Respir Med. 2018, 141, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevaert, P.; Omachi, T.A.; Corren, J.; Mullol, J.; Han, J.; Lee, S.E.; Kaufman, D.; Ligueros-Saylan, M.; Howard, M.; Zhu, R. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in nasal polyposis: 2 randomized phase 3 trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020, 146, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, L.; Platts-Mills, T.A.; Finegold, I.; Schwartz, L.B.; Simons, F.E.R.; Wallace, D.V. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy; Asthma and Immunology joint task force report on omalizumab-associated anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007, 120, 1373–1377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, C. Interleukin-5, eosinophils, and disease. Blood. 1992, 79, 3101–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.A.; Minthorn, E.A.; Beerahee, M. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of mepolizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 monoclonal antibody. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011, 50, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flood-Page, P.T.; Menzies-Gow, A.N.; Kay, A.B.; Robinson, D.S. Eosinophil’s role remains uncertain as anti–interleukin-5 only partially depletes numbers in asthmatic airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003, 167, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, H.G.; Liu, M.C.; Pavord, I.D.; Brusselle, G.G.; FitzGerald, J.M.; Chetta, A.; Humbert, M.; Katz, L.E.; Keene, O.N.; Yancey, S.W.; Chanez, P.; MENSA Investigators. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bel, E.H.; Wenzel, S.E.; Thompson, P.J.; Prazma, C.M.; Keene, O.N.; Yancey, S.W.; Ortega, H.G.; Pavord, I.D. SIRIUS Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, J.E.; d’Ancona, G.; Elstad, M.; Green, L.; Fernandes, M.; Thomson, L.; Roxas, C.; Dhariwal, J.; Nanzer, A.M.; Kent, B.D.; Jackson, D.J. Real-world effectiveness and the characteristics of a ‘super-responder’ to mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest 2020, 158, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazi, A.; Trikha, A.; Calhoun, W.J. Benralizumab – a humanized mAb to IL-5Rα with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity – a novel approach for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012, 12, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolbeck, R.; Kozhich, A.; Koike, M.; Peng, L.; Andersson, C.K.; Damschroder, M.M.; Reed, J.L.; Woods, R.; Dall’acqua, W.W.; Stephens, G.L. MEDI-563, a humanized anti-IL-5 receptor alpha mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010, 125, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, P.; Wenzel, S.; Rabe, K.F.; Bourdin, A.; Lugogo, N.L.; Kuna, P.; Barker, P.; Sproule, S.; Ponnarambil, S.; Goldamn, M.; Zonda Trial Investigators. Oral glucocorticoid–sparing effect of benralizumab in severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 2448–2458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Menzies-Gow, A.; Gurnell, M.; Heaney, L.G.; Corren, J.; Bel, E.H.; Maspero, J.; Harrison, T.; Jackson, D.J.; Price, D.; Lugogo, N.; et al. Oral corticosteroid elimination via a personalised reduction algorithm in adults with severe, eosinophilic asthma treated with benralizumab (PONENTE): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022, 10, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, K.F.; Nair, P.; Brusselle, G.; Maspero, J.F.; Castro, M.; Sher, L.; Zhu, H.; Hamilton, J.D.; Swanson, B.N.; Khan, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in glucocorticoid-dependent severe asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 2475–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanagh, J.E.; Hearn, A.P.; Jackson, D.J. A pragmatic guide to choosing biologic therapies in severe asthma. Breathe (Sheff). 2021, 17, 210144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, S.F.; Roan, F.; Bell, B.D.; Stoklasek, T.A.; Kitajima, M.; Han, H. The biology of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP). Adv Pharmacol. 2013, 66, 129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, S.; O’Connor, B.; Ratoff, J.; Meng, Q.; Mallett, K.; Cousins, D.; Robinson, D.; Zhang, G.; Lee, T.H.; Corrigan, C. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression is increased in asthmatic airways and correlates with expression of Th2-attracting chemokines and disease severity. J Immunol. 2005, 174, 8183–8190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, M.E.; Colice, G.; Griffiths, J.M.; Almqvist, G.; Skärby, T.; Piechowiak, T.; Kaur, P.; Bowen, K.; Hellqvist, A.; Mo, M.; Garcia Gil, G. SOURCE: a phase 3, multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of tezepelumab in reducing oral corticosteroid use in adults with oral corticosteroid dependent asthma. Respir Res. 2020, 21, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AstraZeneca. Update on SOURCE Phase III trial for tezepelumab in patients with severe, oral corticosteroid-dependent asthma. Date date last updated: 22 December 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2020/update-on-source-phase-iii-trial-for-tezepelumab-in-patients-with-severe-oral-corticosteroid-dependent-asthma.html (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Chalitsios, C.V.; McKeever, T.M.; Shaw, D.E. Incidence of osteoporosis and fragility fractures in asthma: a UK population-based matched cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2021, 57, 2001251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, D. B.; Trudo, F.; Voorham, J.; Xu, X.; Kerkhof, M.; Ling Zhi Jie, J.; Tran, T.N. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: Long-term observational study. J. Asthma Allergy. 2018, 11, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, L.; Guyatt, G.; Fink, H. A.; Cannon, M.; Grossman, J.; Hansen, K. E.; Humphrey, M.B.; Lane, N.E.; Magrey, M.; Miller, M.; et al. American college of rheumatology guideline for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo Hernández, A.; Díaz Del Campo Fontecha, P.; Aguado Acín, M.P.; Arboleya Rodríguez, L.; Casado Burgos, E.; Castañeda, S.; Arestè, J.F.; Gifre, L.; Gòmez Vaquero, C.; Rodrìguez, G.C.; et al. Recommendations by the Spanish society of rheumatology on osteoporosis. Reumatol. Clin. Engl. 2019, 15, 188–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, P. J.; Stone, J. H.; Zhang, Y.; Honeyford, K.; Dunn, L.; Logan, R. J.; Butler, C.A.; McGarvey, L.P.A.; Heaney, L.G. Quantification of glucocorticoid-associated morbidity in severe asthma using the Glucocorticoid Toxicity Index. J. Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021, 9, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portacci, A.; Dragonieri, S.; Carpagnano, G.E. Super-Responders to Biologic Treatment in Type 2-High Severe Asthma: Passing Fad or a Meaningful Phenotype? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023, 11, 1417–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caminati, M.; Vaia, R.; Furci, F.; Guarnieri, G.; Senna, G. Uncontrolled Asthma: Unmet Needs in the Management of Patients. J Asthma Allergy. 2021, 14, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutroneo, P.M.; Arzeton, E.; Furci, F.; Scapini, F.; Bulzomì, M.; Luxi, N.; Caminati, M.; Senna, G.; Moretti, U.; Trifirò, G. Safety of Biological Therapies for Severe Asthma: An Analysis of Suspected Adverse Reactions Reported in the WHO Pharmacovigilance Database. BioDrugs. 2024, 38, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weare-Regales, N.; Hudey, S. N.; Lockey, R. F. Practical guidance for prevention and management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis for the allergist/immunologist. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol Pract. 2021, 9, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lommatzsch, M.; Buhl, R.; Canonica, G.W.; Ribas, C.D.; Nagase, H.; Brusselle, G.G.; Jackson, D.J.; Pavord, I.D.; Korn, S.; Milger, K.; et al. Pioneering a paradigm shift in asthma management: remission as a treatment goal. Lancet Respir Med. 2024, 12, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).