1. Introduction

Until now, the mechanisms controlling iron homeostasis during fetal development remain unclear. Both iron deficiency and iron overload during fetal and neonatal period may lead to dysfunction of the developing organs [

1,

2,

3]. Ferritin plays essential roles in cellular and systemic iron homeostasis, sequesters excess intracellular iron, thus protecting cells from oxidative stress, and stores iron for future use in conditions of deficiency or high demand [

2,

4,

5]. Low ferritin concentration is highly specific as an indirect marker for deficiency of total body iron stores. High ferritin concentration may indicate increased iron stores, but it may also be as a result of ferritin being released from damaged cells, increased synthesis and/or increased cellular secretion of ferritin upon various stimuli such as cytokines, oxidants, hypoxia, oncogenes and growth factors [

6].

The complex process of iron homeostasis control in the human body depends on a close coordination of iron absorption, storage and transfer within the body involving proteins with distinct biological functions [

3,

7]. Mammalian iron metabolism is tightly regulated both at cellular and systemic levels [

4]. Sufficient equipment and proper distribution of iron in the intrauterine environment may affect the conditions for fetal growth and development. In the present study, meconium was used as a biological material specific to the fetal development, which contains numerous proteins representing the intrauterine environment [

8]. The selection of proteins to be determined in meconium samples was based on the well-established knowledge of their highly specialized role in maintaining iron homeostasis, including intracellular iron storage function (ferritin - FT, lactoferrin - LTF) [

4,

6,

9,

10], iron transport through the blood to various tissues (transferrin - TF) [

11], iron delivery and export from cells (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

- NGAL) [

12,

13], iron chelation which deprives bacteria of their essential nutrient (calprotectin - protein S100-A8) [

14,

15,

16], heme iron recovery (haptoglobin - HP) [

17], and oxidizing of Fe

2+ (ferrous iron) to Fe

3+ (ferric iron) (ceruloplasmin - CP, myeloperoxidase - MPO) [

18,

19,

20,

21].

The aim of the study was to investigate the relationship between increasing ferritin concentrations in meconium and a panel of proteins, controlling iron metabolism through various mechanisms, which concentrations were adjusted to ferritin tertiles ranges and to assess the possible impact of proteins on the newborn's body size.

2. Results

The mean concentration of ferritin (µg/g) in 122 meconium samples was 78.57 ± 49.6, range 13.01 - 286.25.

Table 1 presents meconium ferritin concentrations in each tertile and the corresponding concentrations of transferrin, haptoglobin, ceruloplasmin, myeloperoxidase, lactoferrin, NGAL and calprotectin measured in meconium.

Statistically significant increases of proteins concentrations in meconium concentrations parallel to ferritin concentrations in consecutive tertiles were found for NGAL only (p<0.05). Considering these changes in NGAL concentrations, parallel to those in ferritin concentrations, meconium concentrations of iron regulatory proteins were compared against NGAL tertiles (

Table 2).

Consecutive NGAL tertiles were associated with increases in lactoferrin, myeloperoxidase, transferrin and haptoglobin concentrations (p<0.05) and calprotectin, ferritin and ceruloplasmin concentrations (p<0.1).

Correlations between individual proteins were assessed for consecutive ferritin tertiles (

Table 3) and consecutive NGAL tertiles (

Table 4).

No correlation was established between meconium ferritin concentration and any of the other proteins (p>0.05). Based on the results presented in

Table 3 two groups of proteins can be distinguished which maintained their correlations in consecutive meconium ferritin tertiles (p<0.05). These are transferrin, haptoglobin and NGAL and the neutrophil-derived proteins lactoferrin, myeloperoxidase and calprotectin. Meconium ceruloplasmin was found to correlate with the neutrophil-derived proteins only (p<0.05). The largest in numbers and the strongest correlations between proteins were found at ferritin concentrations in meconium below 50 µg/g.

Meconium NGAL concentrations were found to significantly correlate with transferrin and haptoglobin (p<0.05). The largest in numbers of correlations between proteins were found at NGAL concentrations in meconium over 2.52 µg/g.

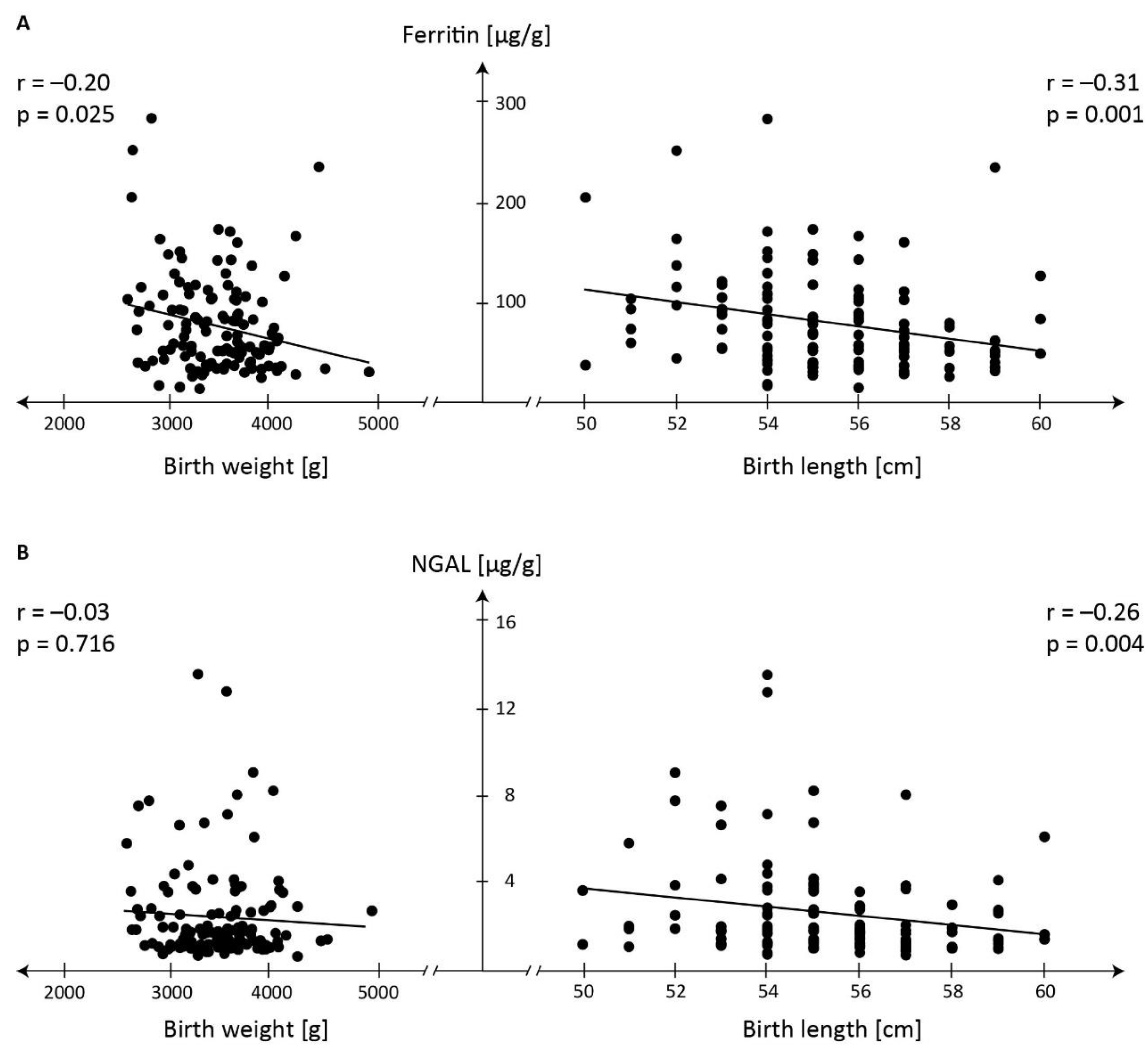

The graph in

Figure 1 shows associations between concentration of ferritin (A) and NGAL concentration (B) in meconium and newborn's body size.

Negative correlations between ferritin concentration in meconium and birth weight and length (r=-0.20, r= -0.31, respectively) and of NGAL and birth length (r= -0.26) indicate involvement of these proteins in fetal development and effect on the size.

3. Discussion

The characteristic associations between ferritin concentrations and a panel of protein regulators of iron metabolism found in meconium at birth may suggest possible non-invasive insight into the iron homeostasis of the intrauterine environment and provide new knowledge about fetal development. Unlike conventional laboratory tests performed in the newborn, measurements of proteins accumulated in the fetal intestine from 12 weeks gestation and excreted with meconium after birth may offer specific information about their involvement in sustained metabolic processes active during the period of fetal development [

22,

23,

24].

A developing fetus needs to be supplied with adequate amounts of iron, which is essential for the key physiological and developmental processes [

25]. At term, 70-80% of fetal iron is present in red blood cells as hemoglobin, 10% in tissues as myoglobin and cytochromes and the remaining 10-15% stored in reticuloendothelial and parenchymal tissues as ferritin and hemosiderin [

2,

26]. In humans, iron incorporated into proteins controls formation of reactive oxygen species, thus protecting cells against damage to the lipid membranes, proteins and DNA, cell death and tissue injury [

25]. Iron endowment of the fetus is entirely dependent on iron transport through the placenta from the maternal circulation and on iron recycling from aged cells [

1,

2,

17,

25,

27,

28]. These processes involve functional proteins which perform the essential task of protecting the body against iron toxicity and at the same time maintaining iron homeostasis.

Meconium contains proteins [

8], whose properties and involvement in the regulation of iron metabolism may explain the role(s) they play during fetal development [

23,

29]. A question arises whether the panel of meconium proteins presented in this study may aid understanding of metabolic processes involved in iron endowment of the fetus. The answer may provide practical diagnostic tools to assess the effect of the intrauterine environment on the fetal health.

The diagnostic significance of high meconium concentrations of ferritin and their variations, presented for the first time in this paper, remains unclear. Ferritin is the most frequently requested laboratory test as an indirect marker for total iron stores, plays essential roles in cellular and systemic iron homeostasis, sequesters excess intracellular iron, thus protecting cells from oxidative stress and stores iron for future use in conditions of deficiency or high demand [

2,

4,

5]. A tight control of iron homeostasis in the body is ensured by functionally differentiated proteins and macrophages which have an essential role in iron recycling in the body [

28]. Macrophages with cytosolic iron deposited in ferritin are considered ‘a relay station’ for iron redistribution [

28,

30]. Macrophages specialized in the ingestion and degradation of red blood cells mainly acquire heme iron, while other types of macrophages to prevent the release of potentially toxic free heme can obtain iron through alternative mechanisms. These include cell-free hemoglobin bound to haptoglobin and the resulting complex bound by macrophage transmembrane receptor CD163 and transferrin-bound iron as the main form of iron present in the bloodstream which delivers iron by transferrin receptor (TFR1) [

30]. Iron overload is a typical effect of iron recycling by reticuloendothelial macrophages. Macrophage-specific mechanisms can internalize large amounts of heme iron also under pathological conditions that are characterized by an oxidative microenvironment and have a remarkable capacity to tolerate iron excess [

28,

30]. These observations from the literature may explain the absence of any changes and correlations between increasing meconium ferritin concentrations and other meconium proteins, except for NGAL, found in this study. Independent of ferritin concentrations, the significant correlations between the meconium concentrations of haptoglobin, transferrin and NGAL are evidence of their shared biological task of controlling intra- and extravascular iron and its delivery to macrophages. The findings indicate a significant interaction between transferrin, NGAL and haptoglobin in their role as a transporter of hemoglobin released from senescent or damaged red blood cells at different anatomical sites in the fetus.

A question arises which properties of NGAL may be responsible for selective adjustment of its concentrations in response to increases in meconium ferritin concentrations. NGAL, a 25 kDa protein secreted mostly by immune cells such as neutrophils, macrophages and dendritic cells is an iron transporter, a member of the lipocalin superfamily. NGAL does not bind iron directly but tightly binds ferric siderophores and is an essential component of the innate immune system. The molecule of NGAL containing iron interacts with receptors on the cell surface, transports iron into the cell and releases it inside. NGAL that is not bound to iron also interacts with the cells surface receptors which results in an intracellular iron transfer out of the cell [

12,

13,

28,

31]. During pregnancy NGAL is expressed in trophoblast cells and its gene is upregulated in cytotrophoblast via stimulation by TNF-alfa. Higher levels of NGAL protein were found in placental tissues of patients with preeclampsia compared with normal pregnancies [

12,

13].

The main features of ferritin and NGAL suggest that the control over iron homeostasis exerted by these proteins plays an essential role in the development of inflammation. Cellular and systemic ferritin levels are not only crucial indicators of iron status but are also important markers of inflammation, and immunological and malignant disorders [

1,

26,

27]. Pathologic conditions are related not only to systemic dysregulation but also affect tissue iron balance. High ferritin may indicate increased iron stores and is also a result of ferritin being released from damaged cells, increased synthesis and increased cellular secretion of ferritin upon stimuli such cytokines, oxidants, hypoxia, oncogenes and growth factors [

6]. NGAL protects against bacterial sepsis and also as an acute phase protein increases inflammatory states involved in a variety of physiological and pathophysiological processes such as arterial hypertension, apoptosis, infection, immune response and metabolic complications such as obesity, diabetes, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and gestational diabetes [

12,

13,

31]. Negative correlations between meconium ferritin and NGAL concentrations and birth weight and length found in this study may indicate an adverse effect of high concentrations of the two proteins on newborn body measurements.

The findings of the present study distinguish specific properties of NGAL in meconium, as the significant correlations between its concentrations and those of transferrin and haptoglobin and of neutrophil granule proteins support its special role in the intrauterine environment. The correlations between the meconium concentrations of proteins present in neutrophils may provide additional information from this study about the function of one of a host of innate immune cells detected at the maternal-fetal interface [

32,

33].

Additionally, our findings indicate individual correlations between ceruloplasmin and neutrophil granule proteins in meconium. As observed by Sokolov et al. [

34], ceruloplasmin is involved in the regulation of neutrophils, which suggests that it may also control neutrophils during fetal development.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Group

A total of 122 neonates 36 to 41 weeks gestation, with birth weight [g] above 2500, mean±SD: 3511±426 and birth length [cm]: mean±SD: 55±2, born in the Department of Obstetrics, Women’s Diseases and Gynecologic Oncology at the Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration (present name The National Medical Institute of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration) in Warsaw. The study was conducted from 2021 to 2023.

The inclusion criteria were singleton deliveries with clear amniotic fluid, and the neonates did not pass meconium in the uterus or during delivery, but after birth. The women giving birth had no anemia or clinical signs associated with an acute or chronic hypoxic event. The exclusion criteria were multiple pregnancies, colored amniotic fluid, and birth weight below 2500 g. At the time of birth, a qualified medical professional conducted measurements of each neonate's weight and length. Weight measurements were recorded in grams, while length measurements, measured in centimeters, extended from the top of the head to the heel of the foot and were rounded to the nearest centimeter. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians prior to inclusion of the neonates in the study. This study was performed in line with principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Committee for Human Experiments at the Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration (The National Medical Institute of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration) in Warsaw (Decision No. 71/2011).

4.2. Meconium Collection and Homogenate Preparation

The sample of first meconium was collected from a neonate in the hospital ward from the nappy with a disposable spatula and transferred into a 50-mL graduated plastic tube and frozen at −20 °C for up to 7 days, and next, a meconium homogenate was prepared. The empty tubes were weighed prior to adding the meconium and reweighed after filling. The date, time, and weight of each meconium collection were recorded. The weight of the meconium sample (n = 122) ranged from 0.484 to 9.899 g (mean ± SD 5.105 ± 2.442; median 5.174).

To prepare the homogenate, PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline pH 7.4) was added to a tube with the meconium: one part by weight of meconium per four parts by weight of PBS added in two equal portions. After the first PBS portion was added, the tube was placed on a hematology mixer for 15 min and then shaken in a horizontal position using an LP300Hk shaker for 1 h. After adding the second PBS portion, the procedure was repeated. The homogenate was transferred to Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80 °C. Prior to protein measurements, the homogenates were thawed for 24 h in a refrigerator. Next, they were mixed on a hematology mixer at room temperature for one hour.

4.3. Laboratory Methods

Meconium proteins were measured by ELISA using Assaypro LLC ELISA kits (St. Charles, MO 63301, USA, www. assaypro.com) according to the manufacturer‘s instructions for each individual protein. The following kits were used: AssayMaxTM Human Lactoferrin ELISA Kit, AssayMaxTM Human Lipocalin-2 ELISA Kit, AssayMaxTM Human Myeloperoxidase (MPO) ELISA Kit, AssayMaxTM Human Calprotectin ELISA Kit, AssayMaxTM Human Ceruloplasmin ELISA Kit, AssayMaxTM Human Haptoglobin ELISA Kit, AssayMaxTM Human Ferritin ELISA Kit, AssayMaxTM Human Transferrin ELISA Kit.

Measurements were performed in accordance with the principles of Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) in duplicate, and then the mean value was calculated and reported as a final concentration.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistica Version 13 software, developed by Stat Soft Inc. (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, California, USA). The normality of distributions of iron regulatory proteins in the meconium ferritin and NGAL tertiles and of birth weights and lengths was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Since distributions were other than the normal, the non-parametric tests were used. The Spearman test was used to determine coefficients of correlation (r) between concentrations of proteins in each tertile. The Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA test and the median test were applied to compare and assess differences in concentrations of individual proteins between tertiles. The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median, range. A statistical significance level of p < 0.05 was considered for all analyses.

5. Conclusions

The panel of proteins determined in meconium and involved in iron metabolism may indicate their role in the development of a fetus. Parallel increases in the meconium concentrations of ferritin and NGAL may be specifically characteristic for neonates with low body size. The correlations between the meconium concentrations of transferrin, haptoglobin and NGAL may indicate their shared involvement in iron transport in the intrauterine environment. The characteristic associations between NGAL and measured proteins may indicate the individual role of NGAL in the control and transport of iron in the intrauterine environment. The presence of ceruloplasmin in meconium and the demonstrated correlations may confirm its involvement in neutrophil control in the intrauterine environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and B.L.-M.; methodology, E.S.; software, E.S.; validation, E.S.; formal analysis, E.S.; investigation, E.S. and B.L.-M.; data curation, E.S., B.L.-M., T.I. and A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S. and B.L.-M.; writing—review and editing, E.S., A.J. and B.L.-M.; visualization, E.S.; supervision, B.L.-M., T.I. and A.J.; project administration, B.L.-M., A.J. and T.I.; funding acquisition, A.J. and T.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Institute of Mother and Child nr OPK 510-15-31.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local Committee for Human Experiments at the Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration in Warsaw (Decision No. 71/2011), Approval date: 7 December 2011.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sangkhae V, Fisher AL, Wong S, Koenig MD, Tussing-Humphreys L, Chu A, et al. Effects of maternal iron status on placental and fetal iron homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(2):625-40. [CrossRef]

- Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(4):516-24.

- Dev S, Babitt JL. Overview of iron metabolism in health and disease. Hemodial Int. 2017;21 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S6-s20. [CrossRef]

- Kotla NK, Dutta P, Parimi S, Das NK. The Role of Ferritin in Health and Disease: Recent Advances and Understandings. Metabolites. 2022;12(7). [CrossRef]

- Kämmerer L, Mohammad G, Wolna M, Robbins PA, Lakhal-Littleton S. Fetal liver hepcidin secures iron stores in utero. Blood. 2020;136(13):1549-57. [CrossRef]

- Sandnes M, Ulvik RJ, Vorland M, Reikvam H. Hyperferritinemia-A Clinical Overview. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9). [CrossRef]

- Holbein BE, Lehmann C. Dysregulated Iron Homeostasis as Common Disease Etiology and Promising Therapeutic Target. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(3). [CrossRef]

- Lisowska-Myjak B, Skarżyńska E, Wojdan K, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A. Protein and peptide profiles in neonatal meconium. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45(3):556-64. [CrossRef]

- Kolstø Otnaess AB, Meberg A, Sande HA. Plasma lactoferrin measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Measurements on adult and infant plasma. Scand J Haematol. 1983;31(3):235-40. [CrossRef]

- Cao X, Ren Y, Lu Q, Wang K, Wu Y, Wang Y, et al. Lactoferrin: A glycoprotein that plays an active role in human health. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1018336. [CrossRef]

- DePalma RG, Hayes VW, O'Leary TJ. Optimal serum ferritin level range: iron status measure and inflammatory biomarker. Metallomics. 2021;13(6). [CrossRef]

- Romejko K, Markowska M, Niemczyk S. The Review of Current Knowledge on Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL). Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13). [CrossRef]

- Yin X, Huo Y, Liu L, Pan Y, Liu S, Wang R. Serum Levels and Placental Expression of NGAL in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Endocrinol. 2020;2020:8760563. [CrossRef]

- Jarlborg M, Courvoisier DS, Lamacchia C, Martinez Prat L, Mahler M, Bentow C, et al. Serum calprotectin: a promising biomarker in rheumatoid arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):105. [CrossRef]

- Jukic A, Bakiri L, Wagner EF, Tilg H, Adolph TE. Calprotectin: from biomarker to biological function. Gut. 2021;70(10):1978-88. [CrossRef]

- Nakashige TG, Zhang B, Krebs C, Nolan EM. Human calprotectin is an iron-sequestering host-defense protein. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(10):765-71. [CrossRef]

- Fagoonee S, Gburek J, Hirsch E, Marro S, Moestrup SK, Laurberg JM, et al. Plasma protein haptoglobin modulates renal iron loading. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(4):973-83. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Wang M, Zhang C, Zhou S, Ji G. Molecular Functions of Ceruloplasmin in Metabolic Disease Pathology. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2022;15:695-711. [CrossRef]

- Samygina VR, Sokolov AV, Bourenkov G, Petoukhov MV, Pulina MO, Zakharova ET, et al. Ceruloplasmin: macromolecular assemblies with iron-containing acute phase proteins. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67145. [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Penha L, Caldeira-Dias M, Tanus-Santos JE, de Carvalho Cavalli R, Sandrim VC. Myeloperoxidase in Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Its Relation With Nitric Oxide. Hypertension. 2017;69(6):1173-80. [CrossRef]

- Mayyas FA, Al-Jarrah MI, Ibrahim KS, Alzoubi KH. Level and significance of plasma myeloperoxidase and the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with coronary artery disease. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8(6):1951-7. [CrossRef]

- Lisowska-Myjak B, Wilczyńska P, Bartoszewicz Z, Jakimiuk A, Skarżyńska E. Can aminopeptidase N determined in the meconium be a candidate for biomarker of fetal intrauterine environment? Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2020;115:104446.

- Skarżyńska E, Mularczyk K, Issat T, Jakimiuk A, Lisowska-Myjak B. Meconium Transferrin and Ferritin as Markers of Homeostasis in the Developing Fetus. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(21). [CrossRef]

- Shitara Y, Konno R, Yoshihara M, Kashima K, Ito A, Mukai T, et al. Host-derived protein profiles of human neonatal meconium across gestational ages. Nature Communications. 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Gammella E, Correnti M, Cairo G, Recalcati S. Iron Availability in Tissue Microenvironment: The Key Role of Ferroportin. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6). [CrossRef]

- Siddappa AM, Rao R, Long JD, Widness JA, Georgieff MK. The assessment of newborn iron stores at birth: a review of the literature and standards for ferritin concentrations. Neonatology. 2007;92(2):73-82. [CrossRef]

- Shao J, Lou J, Rao R, Georgieff MK, Kaciroti N, Felt BT, et al. Maternal serum ferritin concentration is positively associated with newborn iron stores in women with low ferritin status in late pregnancy. J Nutr. 2012;142(11):2004-9. [CrossRef]

- Jung M, Weigert A, Mertens C, Rehwald C, Brüne B. Iron Handling in Tumor-Associated Macrophages-Is There a New Role for Lipocalin-2? Front Immunol. 2017;8:1171.

- Skarżyńska E, Jakimiuk A, Issat T, Lisowska-Myjak B. Meconium Proteins Involved in Iron Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(13). [CrossRef]

- Recalcati S, Cairo G. Macrophages and Iron: A Special Relationship. Biomedicines. 2021;9(11). [CrossRef]

- Abella V, Scotece M, Conde J, Gómez R, Lois A, Pino J, et al. The potential of lipocalin-2/NGAL as biomarker for inflammatory and metabolic diseases. Biomarkers. 2015;20(8):565-71.

- Bert S, Ward EJ, Nadkarni S. Neutrophils in pregnancy: New insights into innate and adaptive immune regulation. Immunology. 2021;164(4):665-76. [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-Molina B, Muller I, Kropf P, Sykes L. The Role of Neutrophils in Pregnancy, Term and Preterm Labour. Life (Basel). 2022;12(10). [CrossRef]

- Sokolov AV, Zakharova ET, Kostevich VA, Samygina VR, Vasilyev VB. Lactoferrin, myeloperoxidase, and ceruloplasmin: complementary gearwheels cranking physiological and pathological processes. Biometals. 2014;27(5):815-28.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).