1. Introduction

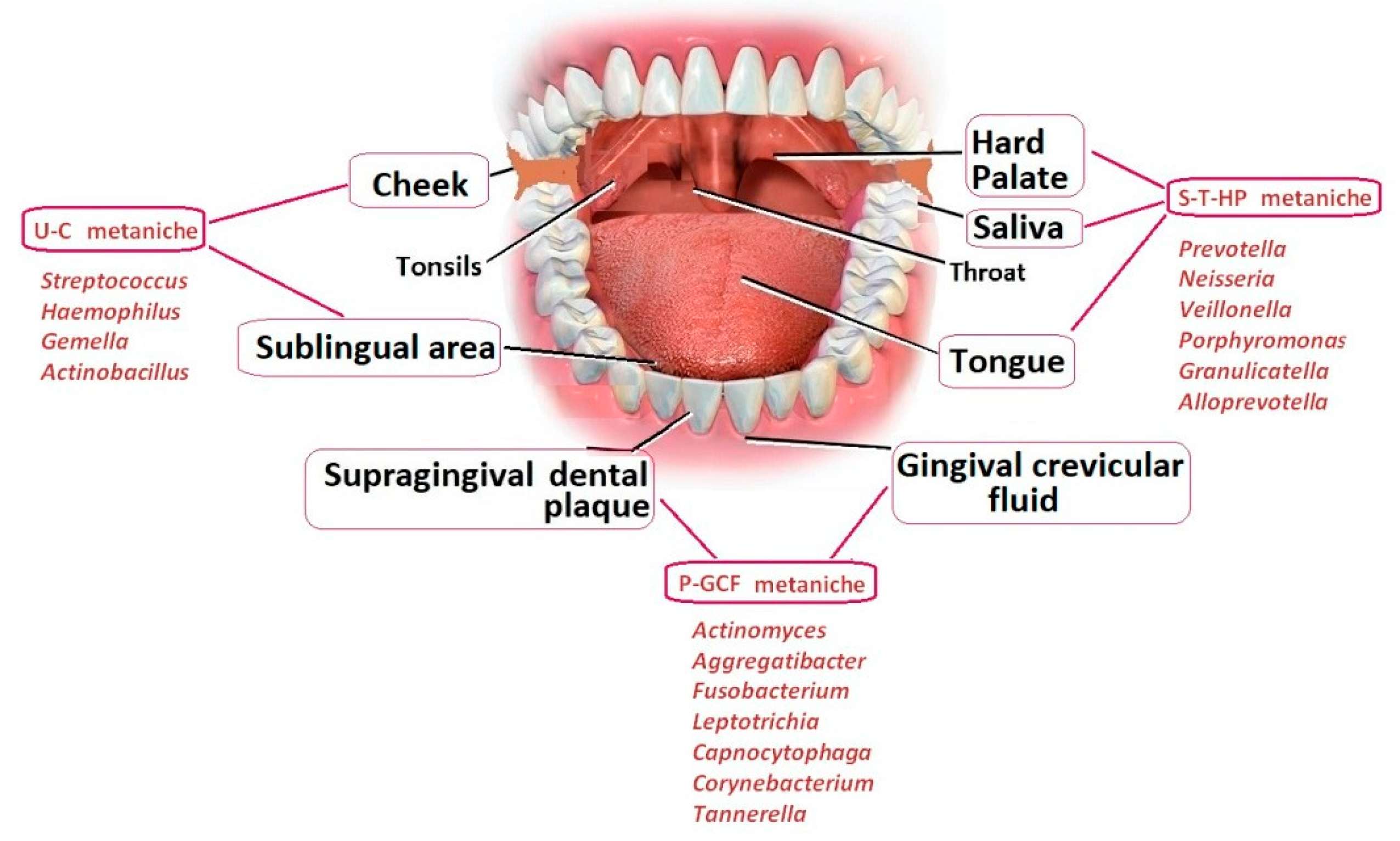

The human microbiome is known to play a role in the development of major systemic diseases. In particular, experimental and clinical studies suggest a possible link between these biomarkers, oral health and cognitive decline. The mechanism by which the oral microbiota, the second most diverse and populous one in the mammalian body (as shown in

Figure 1 by Orr, Miranda E et al, 2020), affects cognition is likely to be mediated by modifications in the oral microenvironment that select for pathogens and facilitate the transmission of bacteria outside the mouth [

1].

Different species of Spirochaetes were correlated to various neurodegenerative diseases and other pathologies, particularly the genus Treponema, a microaerophilic bacterium that survives for short time outside the infected organism. It is closely related (>99% DNA homology) with other species that were falling in the Spirochaete Phylum. Pathogenic Treponemes are not culturable in the laboratory, unlike nonpathogenic Treponemes; in fact, we can distinguish: the Treponema pallidum, the etiologic agent of syphilis, the Treponema carateum that causes pinta, the Treponema pertenue, the etiologic agent of framboesia and the Treponema endemicum that causes bejel or "endemic syphilis." [

2]. Previous reports have also documented amplification of T. pallidum nucleic acid from oral or pharyngeal swabs [

3,

4], or in one instance, saliva [

5], in individuals with syphilis.

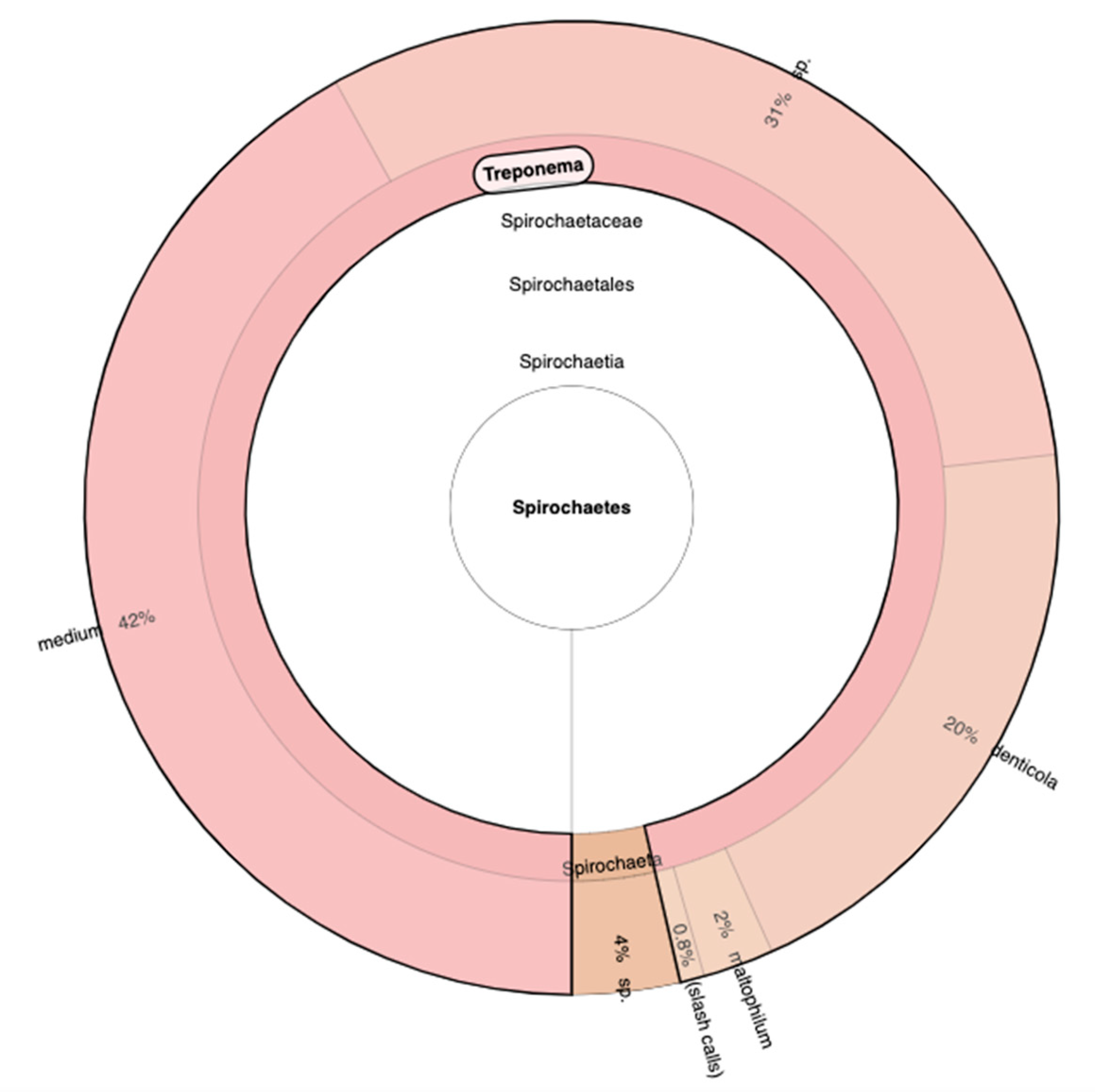

Actually, Spirochaetes are highly neurotropic and can spread along nerve fibers and the lymphatic system. They have been identified in the trigeminal nerve and ganglia, which might be the preferential access to brain. It has also been shown that typical oral species of the phylum Spirochaetes (including multiple species of the genus Treponema) often comprise amyloid plaques (as shown in

Figure 2 by Bacali C et al, 2022) [

6].

In 2021, Su et al. confirmed that oral Treponema denticola can induce β-amyloid accumulation in the hippocampus of C57BL/6 mice [

7].

Here we present a patient with dementia tested for Huntington disease, which resulted with a normal number of CAG repeat in HTT gene but presented, at oral microbiome analysis from buccal swabs, the presence of a new Phylum that we had never encountered, the Spirochaetes Phylum, of which 20% represented by the species denticola. Our goal is to understand if beyond the genetic diagnostic test, it was a particular condition linked to dementia that was proinflammaging for the patient.

2. Case Presentation

We describe the case of an 83-year-old woman, evaluated genetically due to dementia and late-onset dyskinesia. At first the neurologist made the diagnosis of Lewy Body Dementia but then she had been started to present akathisia, and somatic dyskinesia involving even the diaphragm and the abdomen. Moreover, she was suffering of sleep disorder, complex mood disorder, psychosis including unintelligible confabulations, and parkinsonism. Last head CT scan revealed signs of marked cerebral atrophy and slight pallidal calcifications. Her medical history included previous deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and femoral fracture. She’s being treated with Pradaxa, Xenazine, Madopar, Astazin, Quietapine and Tavor. She was an elementary school teacher and there was no clear family history of neurodegenerative disorders. She is a widow and has two sons. Genetic testing for Huntington disease revealed a normal number of CAG repeats. However, when we processed the extraction of DNA to perform the analysis we noticed an unparalleled reaction, in the filter column we usually use for the buccal swab with the buffer reaction. Generally, when we perform the extraction of the DNA, we obtain a transparent colour of the elution of DNA. In this case, after centrifugation and before to proceed for the authomatic extraction of DNA, we observed a black volume of elution. This led us to consider whether any medications the patient was taking might have interfered with the reaction. After a careful literature review, we came to no conclusion and consequently decided to proceed with an analysis of the oral microbiota to assess the presence of possible pathogens.

3. Materials and Methods

Starting from buccal swab, bacterial DNA was extracted using the MagPurix instrument and the Bacterial DNA Extraction Kit (Zinexts Life Science Corp, Taipei, Taiwan-CatZP02006), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The bacterial DNA was quantified with Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (ThermoFisher). NGS was performed with the Ion 16S™ Metagenomics Kit, designed for analyses of mixed microbial populations using the Ion Torrent™ semiconducter sequencing workflow. The kit permits PCR amplification of hypervariable regions of the 16S rDNA gene from bacteria. The kit includes two primer sets that selectively amplify the corresponding hypervariable regions of the 16S region in bacteria:

Primer set V2-4-8

Primer set V3-6, 7-9

After quantification of libraries with the Real-Time Step One PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), the amplified fragments can then be sequenced using the Ion S5™ (ThermoFisher) platform, loaded onto an Ion 520TM chip and analyzed using the Ion 16S™ metagenomics analyses module within the Ion Reporter™ software, enabling a rapid and semi-quantitative assessment of complex microbial samples. These comprehensive primer sets allow for accurate detection and identification of a broad range of bacteria down to the genus or species level. The primer sets are paired with Environmental Master Mix v2.0 that is optimized to tolerate high levels of PCR inhibitors and amplify targets from complex samples such as environmental, food, tissue and other challenging samples. The combination of the two primer pools allows for sequence-based identification of a broad range of bacteria within a mixed population.

4. Results

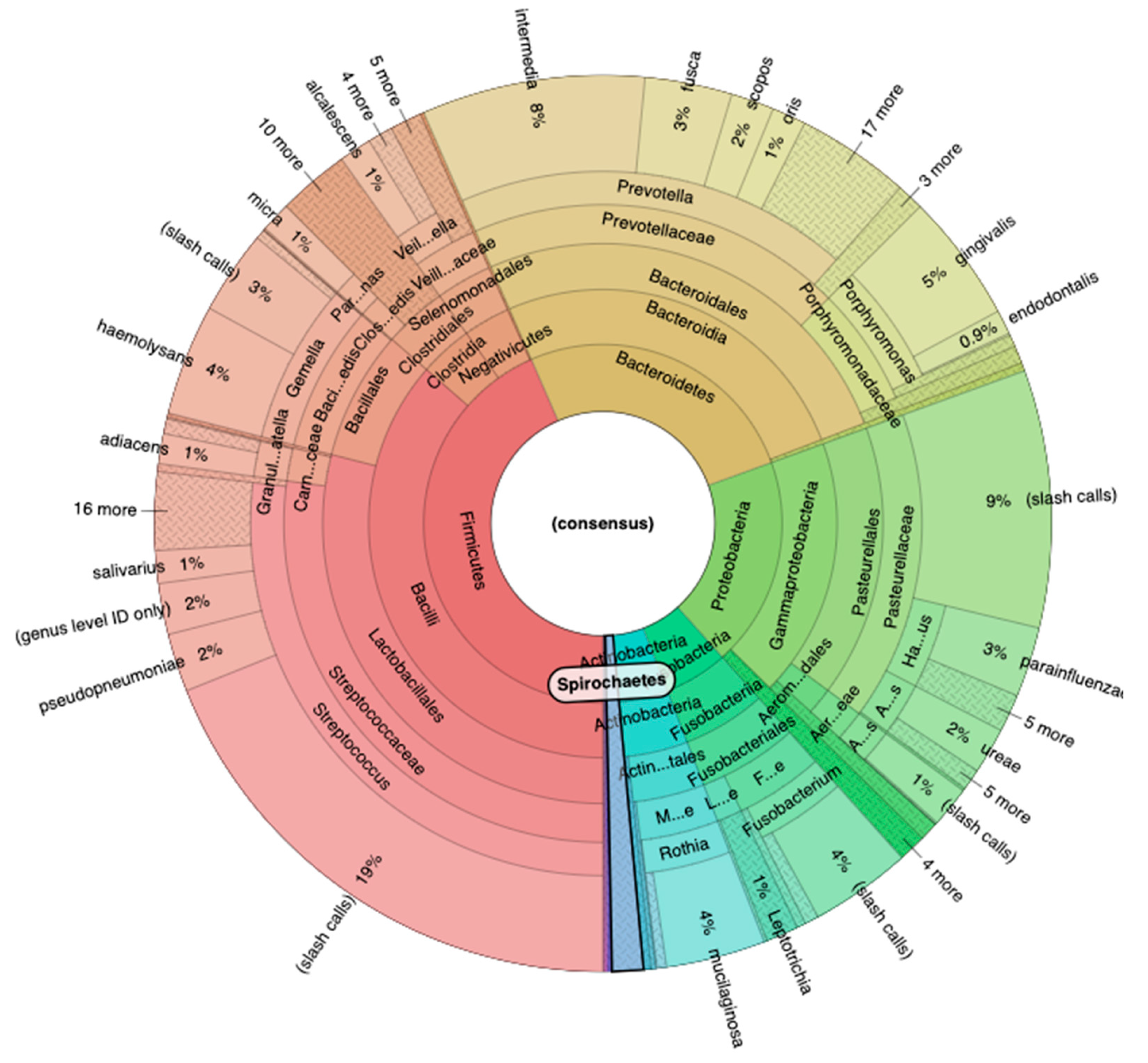

The sequencing performed with 16S Metagenomics Kit reveled an important result. Using the Ion Reporter Software, with the Krona software we analyzed all the phylogenetic classes, starting from the major Phyla. In particular, the Phylum Firmicutes reveled the 43% of the entire microbial population, while the Phylum Bacteroidetes the 26%, the Phylum Proteobacteria 19%, the Phylum Fusobacteria 6% and Actinobacteria the 4% (

Figure 3).

Due to the characterization of all the bacteria community based on hypervariable regions, we discover and detect with Primer V2, V3, V6, V7 and V8 the presence of a new Phylum that we had never encountered, the Spirochaetes Phylum. In particular, the Genre Treponema was over the 90% of the entire Phylum, and continuing the Phylogenetic analysis, the more abundant species are Medium with 42%, sp. with 31% and Denticola with 20% (

Figure 4)

5. Discussion

Different microorganisms belonging to the oral and intestinal microbiota have been linked to various diseases. Within the Spirochaetes phylum, Treponema denticola is known to be able to migrate to the Central Nervous System (CNS) along the peripheral and central nerves, like the trigeminal pathway which is out of the brain blood barrier control, or lymphatic vessels proven by the finding of the spirochetal chemokine CXCL13 in high concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid but not in the serum. It is the larger bacterium upon which other pathogens, like

P. gingivalis, could easily enter the CNS thanks to the marked neurotrophism displayed by all Spirochaetes. The above-mentioned pathway is likely to evade the initial immune recognition of these microorganisms because of their ability to hide within the ganglia, perhaps for many years, then invading the neighboring areas of the brain, like the locus coeruleus, affecting neurotransmitter release in the host [

8]. Recent research indicates that also oral infections could be possible contributing factors to various neurodegenerative conditions [

9].

More studies are required to establish the causal link between oral infections and neurodegeneration. The research relies on fairly small samples and cross-sectional surveys, which only allow for hypotheses regarding the presence of an oral-brain connection. Therefore, most findings still seem preliminary, as their authors generally acknowledge. To elucidate the nature of the connection between the oral microbiome and the CNS, it is crucial to create and validate a methodological approach grounded in a precise definition of oral dysbiosis and the mental disorders analyzed. The identification of specific oral dysbiosis signatures associated with various mental disorders raises the question of whether the CNS modulate the oral microbiome. This would constitute the complementary element of a bidirectional relationship suggesting the existence of an oral cerebral axis equivalent to the gastrointestinal axis. If the bidirectional connection between the oral microbiome and the CNS were confirmed, rebalancing microbial homeostasis with probiotics could offer a potential therapeutic pathway [

10]. Our study, even if, at the moment, we cannot state with certainty the causal role of our findings, suggests correlations between oral microbiota and cognitive disorders or dementia and supports the hypothesis that analyzing oral other than the fecal microbiota could be potentially useful in diagnostic practice of various diseases. The patient's microbial profile might serve as biomarker for evaluating disease risk, early treatment, assessing therapy response, or guiding new treatments and preventive measures [

6].

6. Conclusions

Future microbiome analysis could become a novel approach for preventing systemic diseases and for applying possible therapies in individuals with dysbiosis or the presence of pathogenic microorganisms, especially in the era of precision medicine. This field is still underexplored, and further research with larger sample sizes and involving various types of mental diseases is necessary to clarify the biological connection or interactions between oral microbiota and all mental health disorders, and to develop consistent patterns to generate more definitive data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M; F.A, and D.C; methodology, F.A; software, M.M. and F.A; validation, M.M and F.A. formal analysis, M.M., F.A. and D.C.; investigation, M.M and D.C.; resources, M.O., I.A., V.G. and L.S; data curation, M.M and F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M and F.A; writing—review and editing, M.M, F.A and D.C; visualization, M.M, F.A. and D.C; supervision, M.O., I.A., V.G. and L.S.; project administration, V.G. and L.S; funding acquisition, M.O., V.G. and L.S; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the subject involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Orr ME, Reveles KR, Yeh C-K, Young EH, Han X. Can oral health and oral-derived biospecimens predict progression of dementia? Oral Dis. 2020; 26:249–258. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ropper AH. Neurosyphilis. Longo DL, editor. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;381:1358–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden M, O’Donnell M, Lukehart S, et al. Treponema pallidum Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing To Augment Syphilis Screening among Men Who Have Sex with Men. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57(8).

- Yang CJ, Chang SY, Wu BR, et al. Unexpectedly high prevalence of Treponema pallidum infection in the oral cavity of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with early syphilis who had engaged in unprotected sex practices. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(8):787 e1–7.

- Wang C, Hu Z, Zheng X, et al. A new specimen for syphilis diagnosis: Evidence by high loads of Treponema pallidum DNA in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. 2020.

- Bacali, C.; Vulturar, R.; Buduru, S.; Cozma, A.; Fodor, A.; Chis, A.; Lucaciu, O.; Damian, L.; Moldovan, M.L. Oral Microbiome: Getting to Know And Befriend Neighbors, a Biological Approach. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 671. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemergut M, Batkova T, Vigasova D, Bartos M, Hlozankova M, Schenkmayerova A, Liskova B, Sheardova K, Vyhnalek M, Hort J, Laczó J, Kovacova I, Sitina M, Matej R, Jancalek R, Marek M, Damborsky J. Increased occurrence of Treponema spp. and double-species infections in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Sci Total Environ. 2022 Oct 20.

- Pisani, F.; Pisani, V.; Arcangeli, F.; Harding, A.; Singhrao, S.K. The Mechanistic Pathways of Periodontal Pathogens Entering the Brain: The Potential Role of Treponema denticola in Tracing Alzheimer ’s Disease Pathology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9386. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano-Kelhoffer, B.; Lorca, C.; March Llanes, J.; Rábano, A.; del Ser, T.; Serra, A.; Gallart-Palau, X. Oral Microbiota, Its Equilibrium and Implications in the Pathophysiology of Human Diseases: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1803. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitre Y, Micheneau P, Delpierre A, Mahalli R, Guerin M, Amador G, Denis F. Did the Brain and Oral Microbiota Talk to Each Other? A Review of the Literature. J Clin Med. 2020 Nov 28;9(12):3876. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).