Submitted:

26 July 2024

Posted:

30 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

2.2. Bacteriophage Isolation, Purification, and Titration

2.3. Spot Assay

2.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.5. DNA Extraction, Whole-Genome Sequencing, and Bioinformatic Analysis

2.6. Optimal Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) of Phage

2.7. Host Range Analysis

2.8. Temperature and pH Stability

3. Results

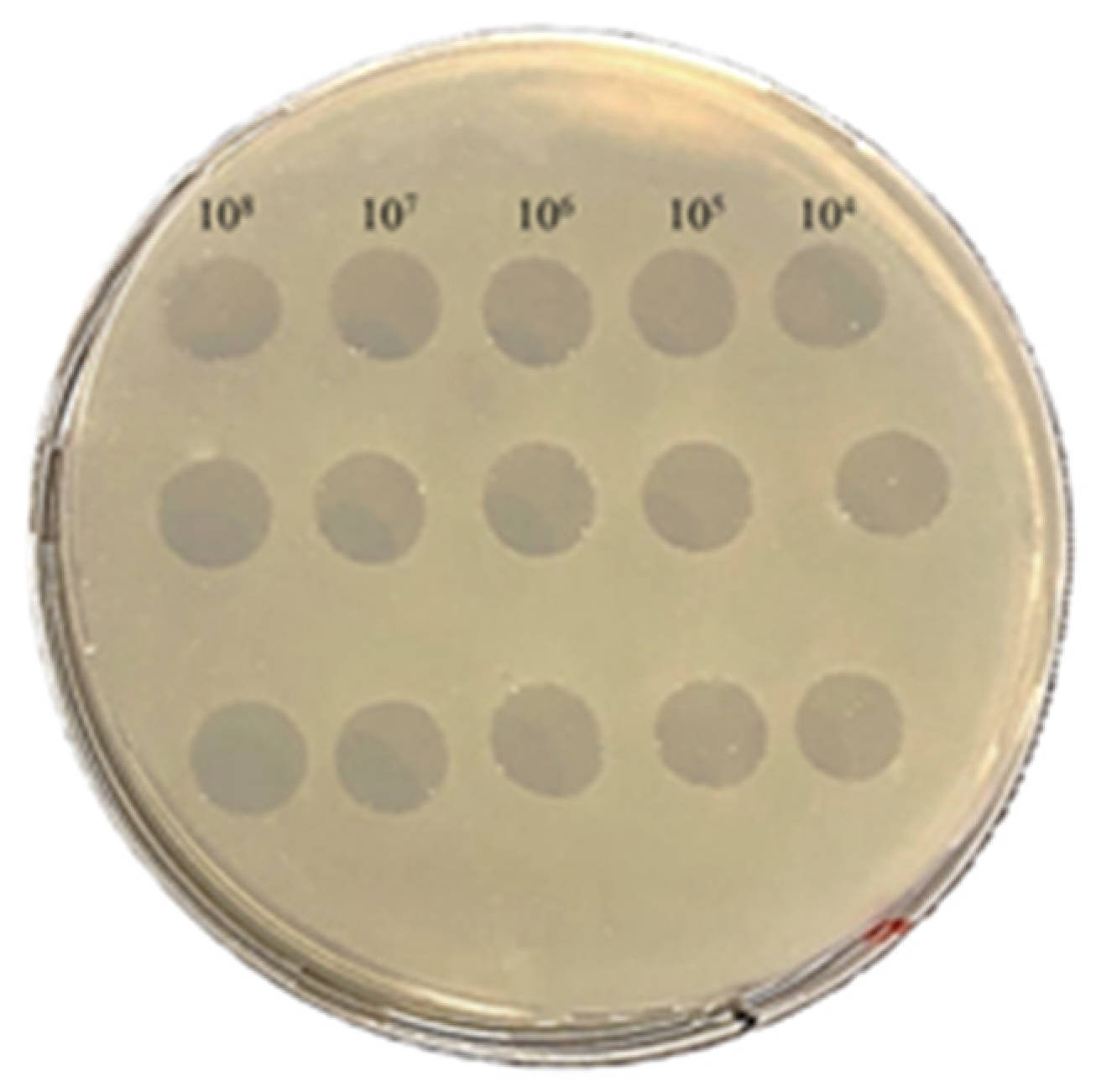

3.1. Spot Assay

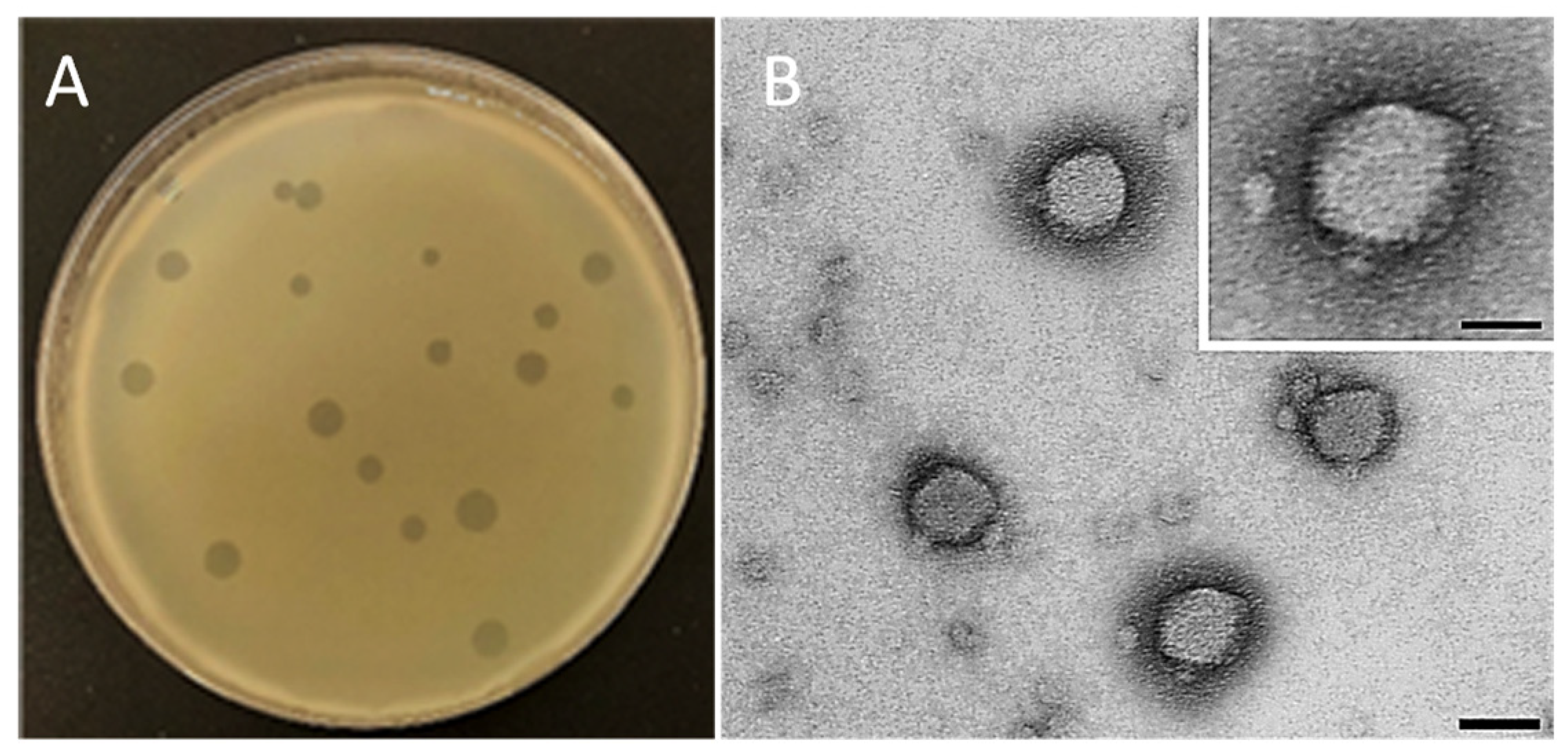

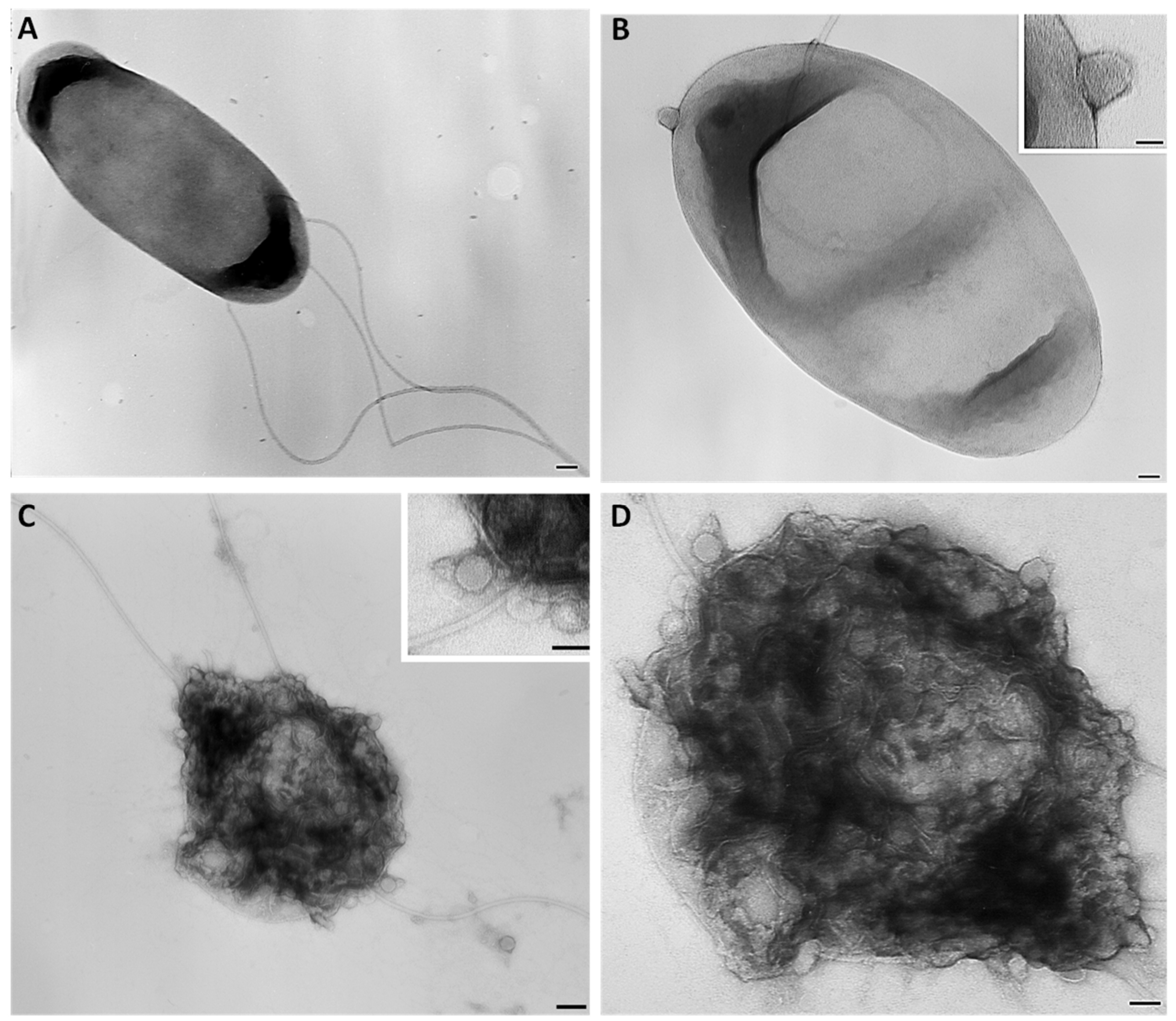

3.2. Morphological and Lytic Properties of PAT1

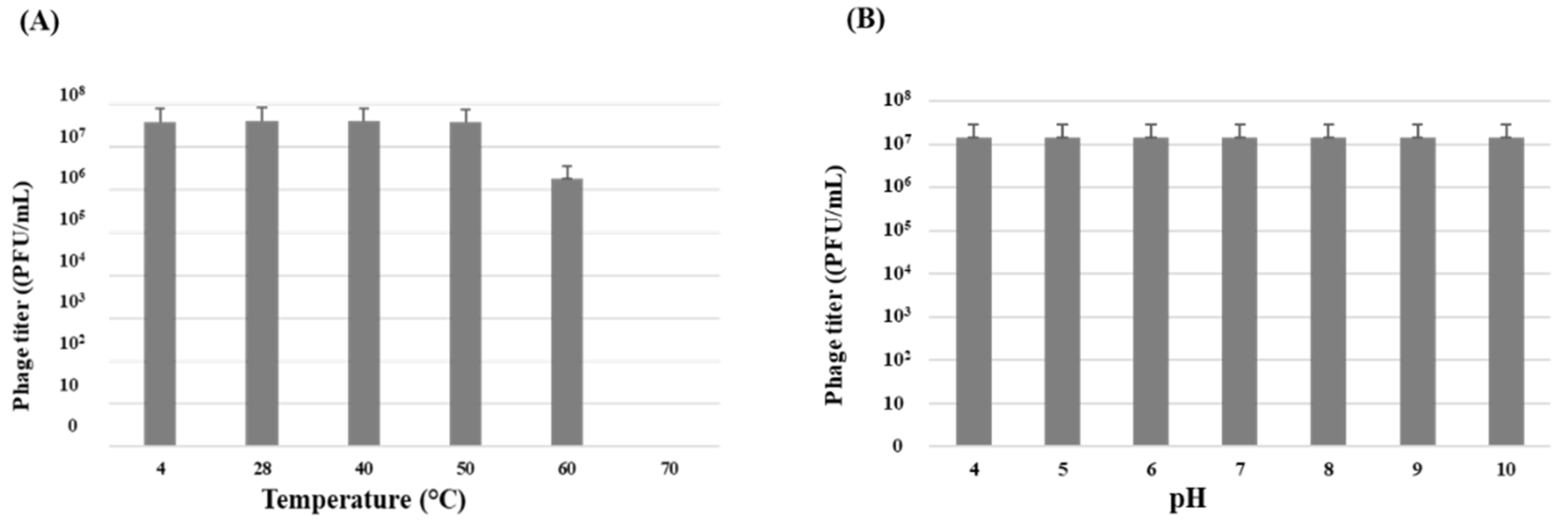

3.3. Phage Stability and Host Range Determination

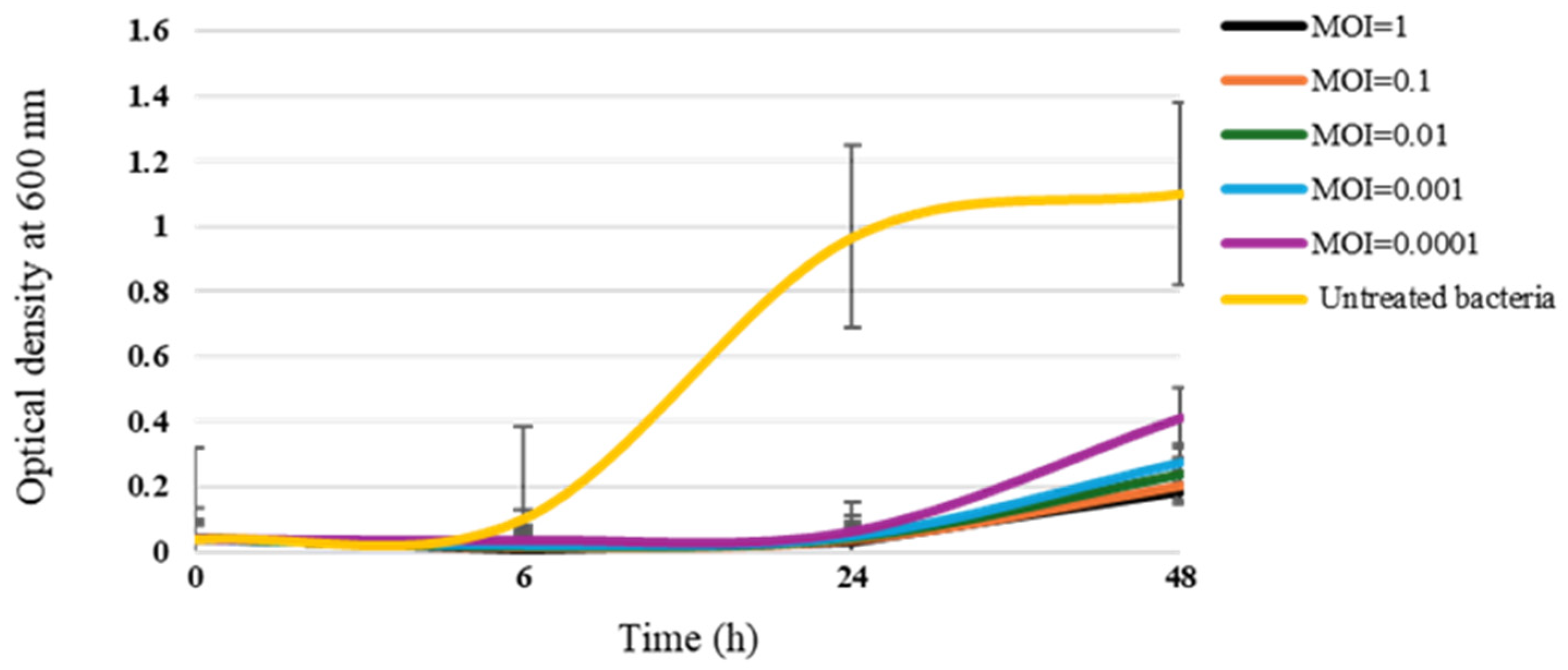

3.4. Bacteriolytic Effect of PAT1 on A. tumefaciens Growth

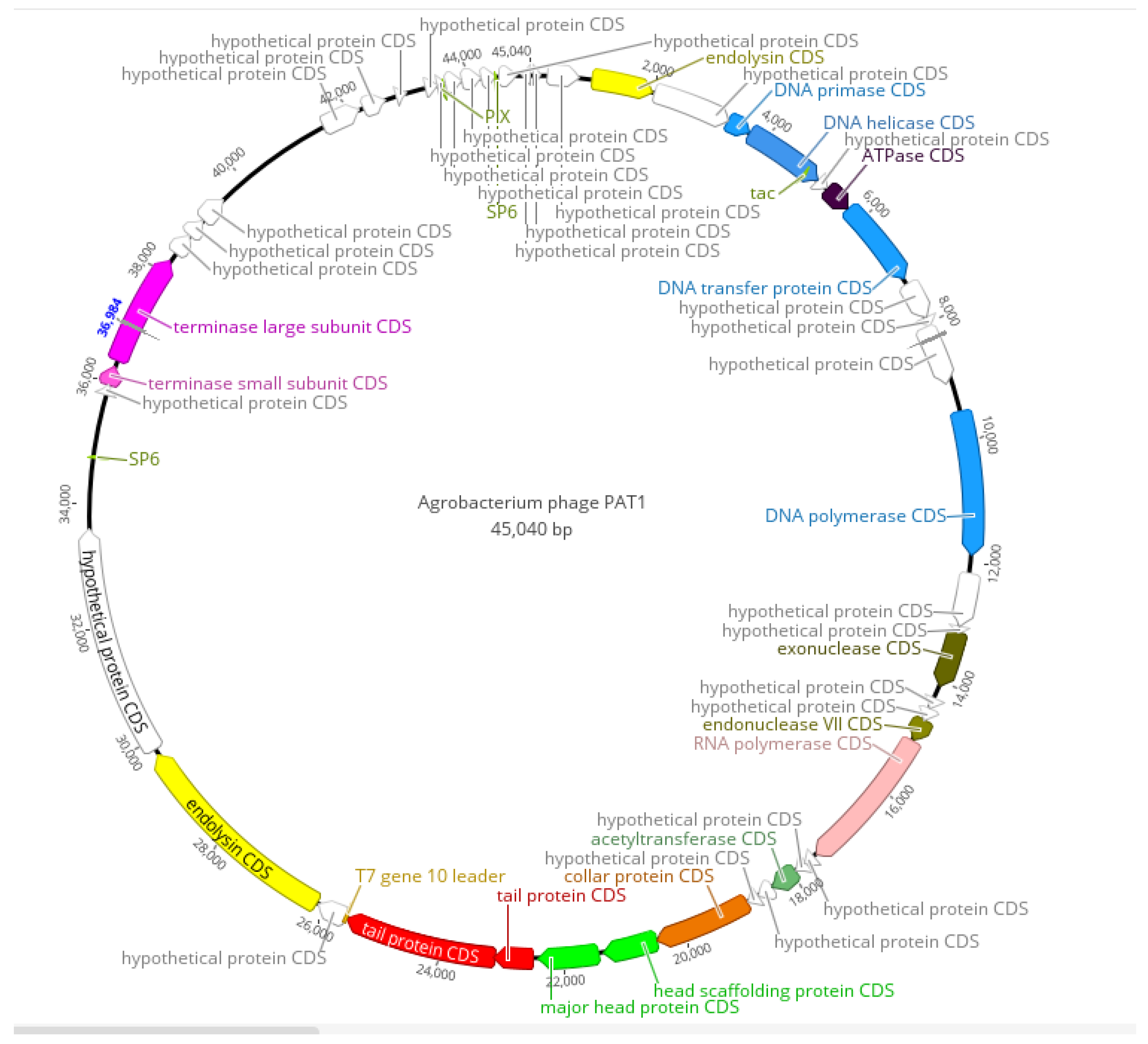

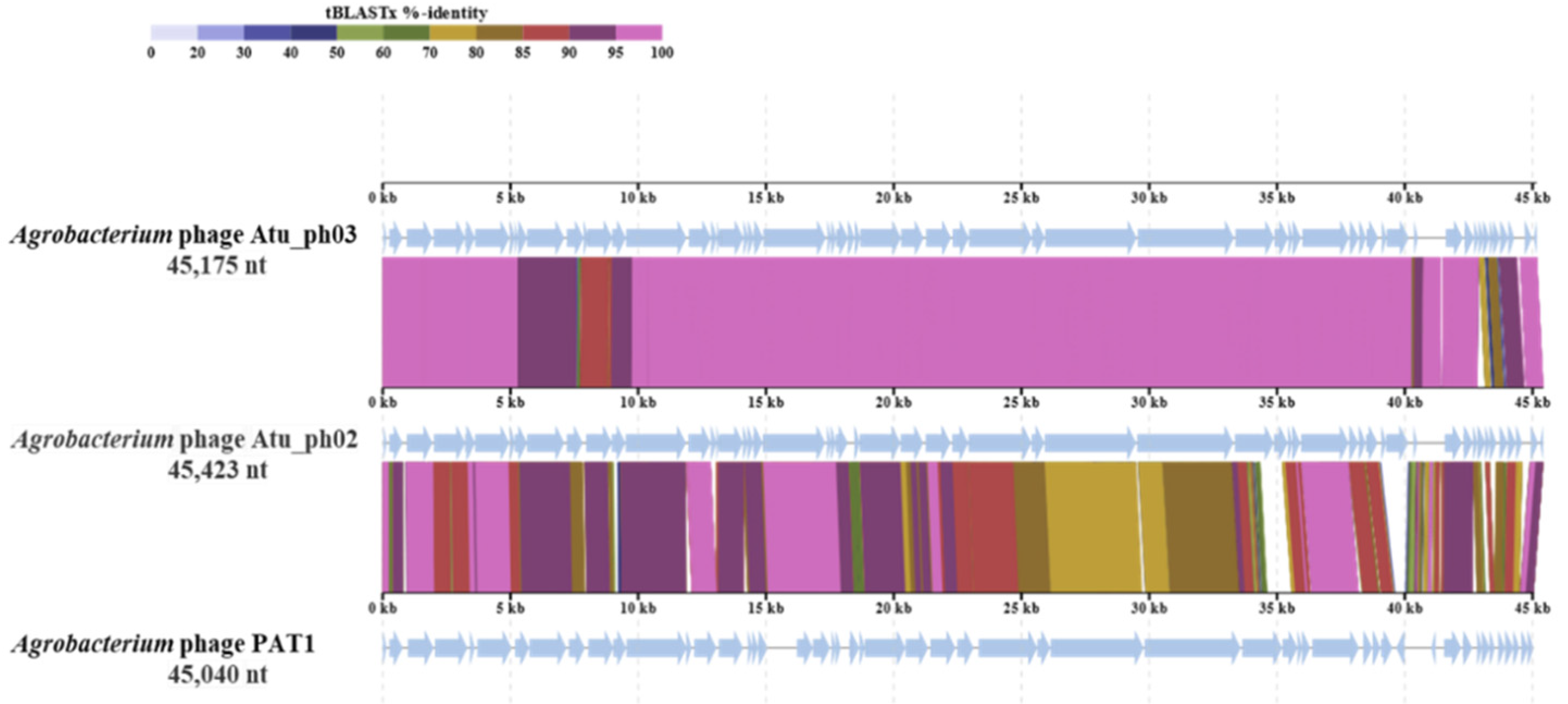

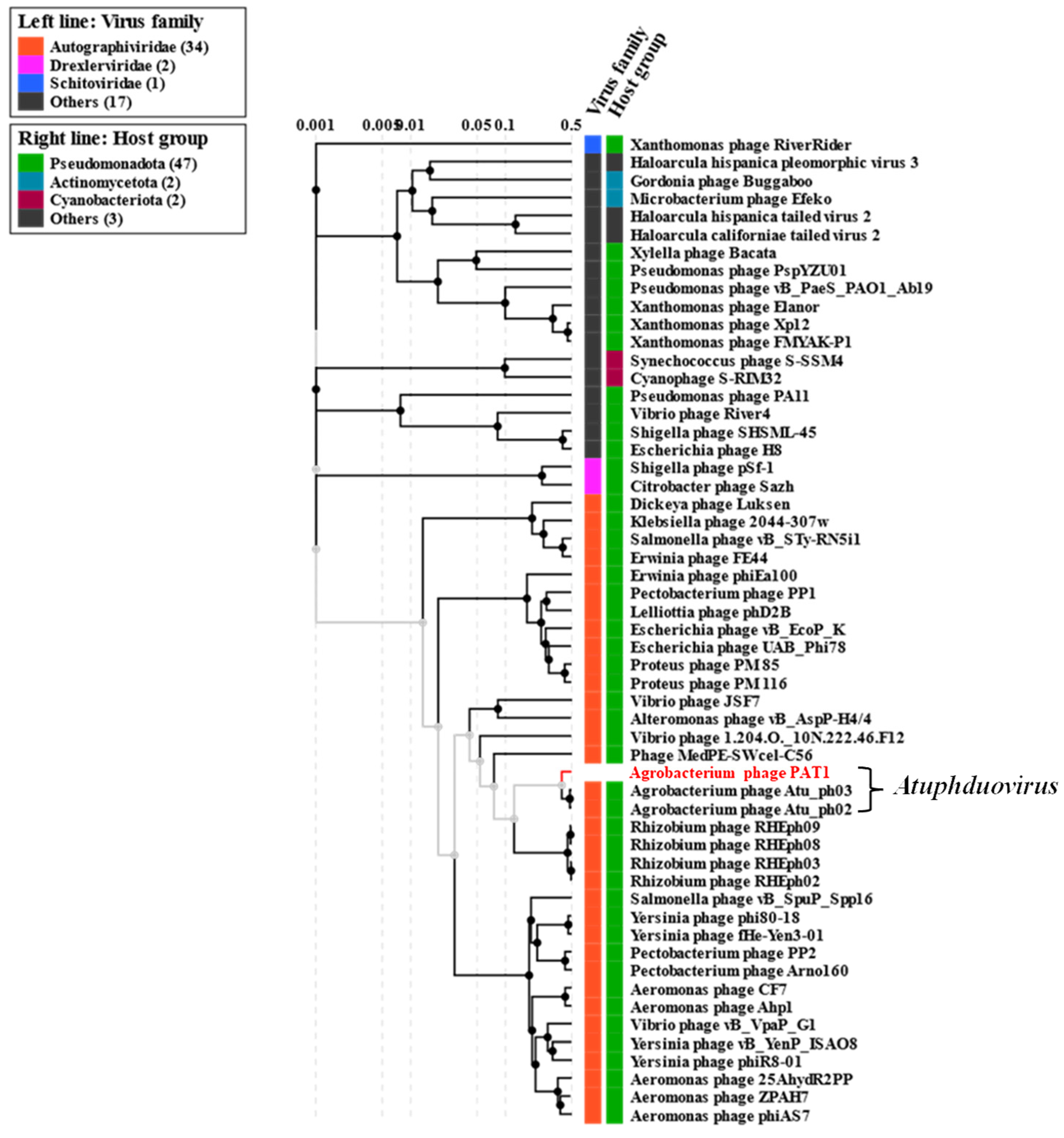

3.5. Genomic and Phylogenetic Analyses of PAT1

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Etminani, F.; Harighi, B.; Mozafari, A.A. Effect of Volatile Compounds Produced by Endophytic Bacteria on Virulence Traits of Grapevine Crown Gall Pathogen, Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 10510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-W.; Efetova, M.; Engelmann, J.C.; Kramell, R.; Wasternack, C.; Ludwig-Müller, J.; Hedrich, R.; Deeken, R. Agrobacterium Tumefaciens Promotes Tumor Induction by Modulating Pathogen Defense in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2948–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, O.; Bae, J.; Kang, B.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Fuqua, C.; Kim, J. Simple and Economical Biosensors for Distinguishing Agrobacterium-Mediated Plant Galls from Nematode-Mediated Root Knots. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 17961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckardt, N.A. A Genomic Analysis of Tumor Development and Source-Sink Relationships in Agrobacterium-Induced Crown Gall Disease in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 3350–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.G.; Moore, W.M.; Hummel, N.F.C.; Pearson, A.N.; Barnum, C.R.; Scheller, H.V.; Shih, P.M. Agrobacterium Tumefaciens: A Bacterium Primed for Synthetic Biology. BioDesign Research 2020, 2020, 8189219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, A.; Nita, M.; Ishii, T.; Watanabe, M.; Noutoshi, Y. Biological Control Agent Rhizobium (=Agrobacterium) Vitis Strain ARK-1 Suppresses Expression of the Essential and Non-Essential Vir Genes of Tumorigenic R. Vitis. BMC Res Notes 2019, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, S.; Harighi, B.; Ashengroph, M.; Clement, C.; Aziz, A.; Esmaeel, Q.; Ait Barka, E. Induction of Systemic Resistance to Agrobacterium Tumefaciens by Endophytic Bacteria in Grapevine. Plant Pathology 2020, 69, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penyalver, R.; Vicedo, B.; López, M.M. Use of the Genetically Engineered Agrobacterium Strain K1026 for Biological Control of Crown Gall. European Journal of Plant Pathology 2000, 106, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicedo, B.; Peñalver, R.; Asins, M.J.; López, M.M. Biological Control of Agrobacterium Tumefaciens, Colonization, and pAgK84 Transfer with Agrobacterium Radiobacter K84 and the Tra- Mutant Strain K1026. Appl Environ Microbiol 1993, 59, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez, B.; López, M.M.; Biosca, E.G. Biocontrol of the Major Plant Pathogen Ralstonia Solanacearum in Irrigation Water and Host Plants by Novel Waterborne Lytic Bacteriophages. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri, M.; El Handi, K.; Valentini, F.; De Stradis, A.; Achbani, E.H.; Benkirane, R.; Resch, G.; Elbeaino, T. Identification and Characterization of Erwinia Phage IT22: A New Bacteriophage-Based Biocontrol against Erwinia Amylovora. Viruses 2022, 14, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svircev, A.; Roach, D.; Castle, A. Framing the Future with Bacteriophages in Agriculture. Viruses 2018, 10, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri, M.; El Handi, K.; Cara, O.; De Stradis, A.; Valentini, F.; Elbeaino, T. Xylella Phage MATE 2: A Novel Bacteriophage with Potent Lytic Activity against Xylella Fastidiosa Subsp. Pauca. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loc-Carrillo, C.; Abedon, S.T. Pros and Cons of Phage Therapy. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropinski, A.M.; Van den Bossche, A.; Lavigne, R.; Noben, J.-P.; Babinger, P.; Schmitt, R. Genome and Proteome Analysis of 7-7-1, a Flagellotropic Phage Infecting Agrobacterium Sp H13-3. Virol J 2012, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attai, H.; Rimbey, J.; Smith, G.P.; Brown, P.J.B. Expression of a Peptidoglycan Hydrolase from Lytic Bacteriophages Atu_ph02 and Atu_ph03 Triggers Lysis of Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017, 83, e01498-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attai, H.; Boon, M.; Phillips, K.; Noben, J.-P.; Lavigne, R.; Brown, P.J.B. Larger Than Life: Isolation and Genomic Characterization of a Jumbo Phage That Infects the Bacterial Plant Pathogen, Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attai, H.; Brown, P.J.B. Isolation and Characterization T4- and T7-Like Phages That Infect the Bacterial Plant Pathogen Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Viruses 2019, 11, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nittolo, T.; Ravindran, A.; Gonzalez, C.F.; Ramsey, J. Complete Genome Sequence of Agrobacterium Tumefaciens Myophage Milano. Microbiol Resour Announc 2019, 8, e00587-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kropinski, A.M.; Mazzocco, A.; Waddell, T.E.; Lingohr, E.; Johnson, R.P. Enumeration of Bacteriophages by Double Agar Overlay Plaque Assay. Methods Mol Biol 2009, 501, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kuronishi, M.; Uehara, H.; Ogata, H.; Goto, S. ViPTree: The Viral Proteomic Tree Server. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2379–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschamps, S.; Mudge, J.; Cameron, C.; Ramaraj, T.; Anand, A.; Fengler, K.; Hayes, K.; Llaca, V.; Jones, T.J.; May, G. Characterization, Correction and de Novo Assembly of an Oxford Nanopore Genomic Dataset from Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 28625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federici, S.; Nobs, S.P.; Elinav, E. Phages and Their Potential to Modulate the Microbiome and Immunity. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.-M.; Xu, W.-M.; Zhang, L. Current Status of Phage Therapy against Infectious Diseases and Potential Application beyond Infectious Diseases. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2022, 2022, 4913146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, A.L. How to Train Your Bacteriophage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2109434118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.-J.; Jia, P.-P.; Yin, S.; Bu, L.-K.; Yang, G.; Pei, D.-S. Engineering Bacteriophages for Enhanced Host Range and Efficacy: Insights from Bacteriophage-Bacteria Interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gencay, Y.E.; Jasinskytė, D.; Robert, C.; Semsey, S.; Martínez, V.; Petersen, A.Ø.; Brunner, K.; de Santiago Torio, A.; Salazar, A.; Turcu, I.C.; et al. Engineered Phage with Antibacterial CRISPR–Cas Selectively Reduce E. Coli Burden in Mice. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egido, J.E.; Costa, A.R.; Aparicio-Maldonado, C.; Haas, P.-J.; Brouns, S.J.J. Mechanisms and Clinical Importance of Bacteriophage Resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2022, 46, fuab048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P.; Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage Host Range and Bacterial Resistance. Adv Appl Microbiol 2010, 70, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knezevic, P.; Aleksic Sabo, V. Combining Bacteriophages with Other Antibacterial Agents to Combat Bacteria. 2019; 257–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guo, Q.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Liu, X. Bacteriophage Endolysin: A Powerful Weapon to Control Bacterial Biofilms. Protein J 2023, 42, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.M.; Rasheed, F.; Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, R. Endolysins: A New Antimicrobial Agent against Antimicrobial Resistance. Strategies and Opportunities in Overcoming the Challenges of Endolysins against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.Y.; Megat Mazhar Khair, M.H.; Song, A.A.-L.; Masarudin, M.J.; Chong, C.M.; In, L.L.A.; Teo, M.Y.M. Endolysins against Streptococci as an Antibiotic Alternative. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischetti, V.A. Development of Phage Lysins as Novel Therapeutics: A Historical Perspective. Viruses 2018, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.-H.; Park, W.B.; Cho, J.E.; Choi, Y.J.; Choi, S.J.; Jun, S.Y.; Kang, C.K.; Song, K.-H.; Choe, P.G.; Bang, J.-H.; et al. Effects of Phage Endolysin SAL200 Combined with Antibiotics on Staphylococcus Aureus Infection. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2018, 62, 10.1128/aac.00731-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, A.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Phage Endolysins: Advances in the World of Food Safety. Cells 2023, 12, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, N.T.; Oh, C.-S. Bacteriophage Usage for Bacterial Disease Management and Diagnosis in Plants. Plant Pathol J 2020, 36, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Isolate | Host plant | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris | CFBP 1710 | Brassica oleracea var. botrytis | France |

| Xanthomonas albilineans | CFBP 1943 | - | Burkina Faso |

| Erwinia amylovora | PGL Z1* | Pyrus communis | Italy |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae | CFBP 311 | Pyrus communis | France |

| Dickeya chrysanthemi biovar chrysanthemi | CFBP 1346 | Chrysanthemum maximum | Italy |

| Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. savastanoi | CFBP 5050 | Olea europaea | Portugal |

| Agrobacterium larrymoorei | CFBP 5473 | Ficus benjamina | USA |

| Agrobacterium rubi | CFBP 5521 | Rubus sp. | Germany |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | CFBP 5770 | Prunus persica | Australia |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | YD 5156-2018 | Prunus domestica | Greece |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | YD 5660-2007 | Prunus dulcis | Greece |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | BPIC 139 | Vitis vinifera | Greece |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | BPIC 284 | Prunus dulcis | Greece |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | BPIC 310 | Pyrus amygdaliformis | Greece |

| Agrobacterium vitis | CFBP 2738 | Vitis vinifera | Greece |

| Agrobacterium vitis | BPIC 1009 | Vitis vinifera | Greece |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).