Generalized resistance to antibiotics increases the pressure to find new effective and safe substances from natural plants. Natural substances and their potential molecules for the treatment of diseases can be effectively mapped with current techniques and the most suitable ones can be selected for further development. Lingonberries have a versatile spectrum of antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiproteolytic, anticarcinogenic and antioxidant effects. The effects of lingonberries are based on the vitamins, minerals, fibers and phenolic compounds they contain. Most of the lingonberry studies have been done with animal experiments, which only give indications of possible effects in humans. A problem in interpreting the research results of clinical human trials has been the fact that berry mixtures have often been used, and thus it has been impossible to determine the effects of lingonberries alone.

This review presents the effects of lingonberry berries, fractions isolated from them in the laboratory, lingonberry juice, lingonberry nectar, lingonberry puree and fermented lingonberry juice on general and oral health and disease prevention, based on the research data accumulated so far on humans and human cells. The interpretation of the results of the studies is complicated by the different isolation methods and concentration of the phenolic substances in the berry fractions, which affect the potency. Web of Science/ Pubmed database searches have been made with the following keywords and their combinations: > Vaccinium vitis- idaea L.> (910/112) > lingonberry > (501/376) > lingonberry fruit > cowberry > cowberries > cowberry fruit > lingonberry juice > fermented lingonberry juice> lingonberry extract > lingonberry fraction > clinical trial> general health > oral > human > cell > in vitro > in vivo > candidiasis, excluding studies with lingonberry leaves or berry mixtures.

Composition of Lingonberries

The composition of lingonberry (

Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) berries has been mapped in numerous studies. The main groups of phenolic substances in lingonberries are flavonoids [anthocyanins, flavonols (quercetin), flavanols (catechins) and phenolic polymers (proanthocyanidins)], phenolic acids, lignans, and stilbenes (resveratrol) [

1]. In addition, lingonberries contain e.g., A, C and E vitamins and minerals that participate in antioxidant reactions, as well as plenty of natural sugars (mainly glucose, fructose and sucrose) 8.2 g/100 g. The profile of lingonberry anthocyanins differs from its close relatives, such as the blueberry (

Vaccinium myrtillus) and cranberry (

Vaccinium oxycoccus L.,

Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) compositions. Lingonberries contain more than 9000 compounds, of which more than 900 are characteristic to lingonberry, especially cyanidin-3-galactoside, cyanidin-3-arabinoside and cyanidin-3-glucoside [

1]. Lingonberries have approximately four times more proanthocyanidins than cranberries. Processing of lingonberries, for example by heating or using different extraction methods of the fractions, causes changes in its composition, which can reduce the antimicrobial effect.

Absorption and Excretion of Lingonberry Polyphenols

The polyphenolic compounds of the lingonberries are fermented by intestinal bacteria (possible prebiotic effect) and excreted in the urine as metabolites. The cyanidin-3-galactoside and its metabolites from whole lingonberry berries are excreted in the urine within 4–12 hours [

2]. Polyphenols isolated from lingonberries by extraction are metabolized in the large intestine by intestinal bacteria, but retain their activity [

3]. According to a study with CaCo-2 cells, the ethanol extract of the lingonberry berries do not significantly affect the absorption of well-absorbed drugs [

4].

Effects on General Health and Disease Prevention

Polyphenolic substances have been found to have a protective effect against many aging-related diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, asthma, damage caused by UV radiation, overweight, diabetes and neurodegeneration [

5]. Wild berries have their characteristic polyphenol composition [

6]. Polyphenols neutralize oxygen radicals and eating enough vegetables and fruits has been found to prevent the occurrence of aging diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and cancer by preventing the oxidation of DNA, proteins and lipids in the body [

7]. Anthocyanidins play an important role in protecting cells from damage caused by oxidation.

In Vitro Studies

Antioxidant Effects

Lingonberry cyanidin-3-galactoside acts as the main antioxidant [

6,

8] and lingonberries have a better antioxidant effect than blueberries, cranberries, raspberries or strawberries [

8]. Lingonberry catechins and procyanidins inhibit the oxidation of human LDL in vitro [

9].

Cancer Cell Studies

The juice squeezed from lingonberries has been found to inhibit the growth of human leukemia cells HL60 by inducing apoptosis, partly based on the antioxidant effect [

8]. Fermented lingonberry juice inhibits the growth and infiltration of aggressive human tongue epithelial carcinoma cells (HSC-3, SCC-25) [

10]. Lingonberry ethanol extract (anthocyanins) has an inhibitory effect on the growth of human estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells (MCF-7, ATCC) and human colon cancer cells (HT29, ATCC) [

11]. The proliferation of human cervical cancer cells (HeLa) and human colon cancer cells (CaCo-2) is inhibited by proanthocyanidins type A and B of lingonberry [

12]. Lingonberry methanol extract inhibits the proliferation of HT-29 and hepatocellular carcinoma cells HEPG2 [

13]. The proanthocyanidin fraction of lingonberry induces apoptosis of SW480 (primary) and SW620 (metastatic) colon cancer cells [

14]. Human malignant melanoma (IGR39, colon adenocarcinoma (HT-29), and human renal cell carcinoma (CaKi-1) cells lose their viability with A-type dimers with proanthocyanidins and quercetin [

15].

Effects on the Liver, Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation, Overweight and Diabetes Risk

Liver α-amylase and α- glucosidase are inhibited and liver glucose uptake is improved by lingonberry extract in human HepG2 cells [

16]. This may be important in preventing overweight and diabetes. Lingonberry polyphenols prevent inflammation caused by obesity-related hypertrophic fat cells and endothelial cell dysfunction in human 3T3-L1 fat cells and HUVEC placental endothelial cells [

17]. Glycosylation - end products (Advanced Glycosylation End products, AGE) cause complications. Lingonberry ethanol extract prevents this [

18]. Lingonberry extract inhibits the pancreatic digestive enzyme lipase, which breaks down triglycerides in the intestines, causing their absorption into the bloodstream to deteriorate. This prevents the development of excess weight. Proanthocyanidins, kaempferol and resveratrol change the macrophages of fat cells into an anti-inflammatory form, reducing the expression of IL-6 and TNF-alpha cytokines, reducing the adverse effects of obesity-related low-grade inflammation, and activating the transcription factor STAT6, affecting gene expression [

19].

Antimicrobial Effects

According to numerous studies, lingonberry has antimicrobial (bacteria, yeasts and viruses) effects. Most microbes are able to use their enzymes to modify the host’s proteins or structures, or to secrete proteins that modulate the virulence of other microbes, influencing the host’s immunological response against pathogens. A dysbiotic microbiome can predispose to disease. Probiotics may prevent the course of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases by improving the dysbiotic gut microbiome [

20] and the symptoms of asthma, allergy and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) through immunomodulation [

21].

Lingonberries inhibit the growth of

Salmonella,

Escherichia coli and staphylococcal bacteria [

22,

23]. Anthocyanin and anthocyanidin fractions inhibit

Neisseria meningitis - adhesion of meningococcal bacteria to human HEC-1B epithelial cells [

24]. Lingonberry fractions inhibit biofilm formation of

S. mutans,

S. sobrinus and

S. sanguinis bacteria [

25]. The effects of fermented lingonberry juice have been studied on oral microbes:

C. albicans, C. dubliniensis,

C. glabrata,

C. krusei and

C. tropicalis,

Fusobacterium nucleatum,

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans,

P. gingivalis,

S. mutans,

S. sanguinis,

S. salivarius and lactobacilli. Fermented lingonberry juice inhibits the growth of yeasts, periodontal pathogens and streptococci [

26], but not lactobacilli. Lactobacilli are considered to be probiotic and health promoting. Laboratory experiments have shown the ability of

C. glabrata cell wall-bound proteases to activate and process pro- matrix metalloprotease-8 (pro-MMP-8) to its active form (aMMP-8) – this MMP-8 activation is inhibited by fermented lingonberry juice [

26]. Lingonberry phenolic compounds have also been found to have antiviral properties and inhibit the replication of influenza A and Coxsackie B1 enteroviruses [

27].

Clinical Trials

General Health and Disease Prevention

When consumed together with sucrose, lingonberries or lingonberry nectar prevent the rise in postprandial glucose and insulin levels and hypoglycemia, as well as the rise in free fatty acids [

28]. The effects are due to the slower breakdown and absorption of sucrose. With light or dark bread, the glucose response was weaker [

29]. This is thought to be due to the weaker inhibition of pancreatic alpha-amylase by phenols compared to alpha- glucose oxidase (specific for sucrose).

There is no clinical evidence of the effects of lingonberry in the prevention of urinary tract infection, but lingonberries contain more dimeric and trimeric proanthocyanidins of type A than cranberry [

V. oxycoccus (European variety)] or

V. macrocarpon [North American variety] [

30]. These A-type proanthocyanidins are thought to be the most important inhibitors of bacterial adhesion.

Oral Effects

Dry mouth caused by drugs, cytostatic and radiation therapy, broad-spectrum antibiotics, aging, ill-fitting prostheses or weakened immunity caused by disease exposes the oral microbiome to changes, such as yeast infection. Reduced salivation weakens the protective effect on the teeth, gums and mucous membranes, which also changes the thickness and composition of the biofilm. Although natural berries are beneficial for health, in addition to active substances, they also contain a lot of natural sugars, such as glucose, fructose and sucrose.

The effect of lingonberry on the mouth has been studied very little. There are six oral clinical studies on humans in the literature [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36], one of which was conducted with lingonberry juice and five with fermented lingonberry juice.

Chronic mucocutaneous 2 ½-year remission of yeast symptoms in an APECED patient with candidiasis without yeast medication was achieved using a fermented lingonberry juice as a mouthwash supplement in oral self-care [

31]. Pale, thick deposits on the mucous membrane of the mouth, which resembled

a Candida infection, have been studied in infants under 12 months of age [

32]. Four children out of 32 had mucosal changes, one of which was confirmed to have

C. parapsilosis by cultivation. Lingonberry juice was compared to lemon juice and soda water administered as drops in the mouth when a change appeared, and follow-up took place after two weeks by calling nursing mothers from the clinic. It was found that acidity alone did not remove the appearance of oral thrush in three children, and their etiology remained unclear.

Fermented lingonberry juice increases saliva secretion, lowers

Streptococcus mutans and

Candida - yeasts, is prebiotic by increasing the amount of lactic acid bacteria, lowers the risk of caries, reduces the amount of plaque and gingivitis. It has a positive effect on the clinical parameters of periodontitis, lowering the levels of active matrix metalloprotease-8 (aMMP-8) in the oral fluid, as well as reducing the low-grade inflammation associated with periodontal diseases, and due to its safety, it is well suited to support oral self-care. Lingonberry mouthwash enhances tooth brushing, maintenance of oral hygiene and contributes to the control of plaque [

33,

34,

35,

36,38]. Fermented lingonberry mouthwash has been developed for safe oral use: the sugars have been reduced to a fraction using a patented method. Reducing sugars is essential because oral microbes such as

Candida yeasts and streptococci use sugars for food.

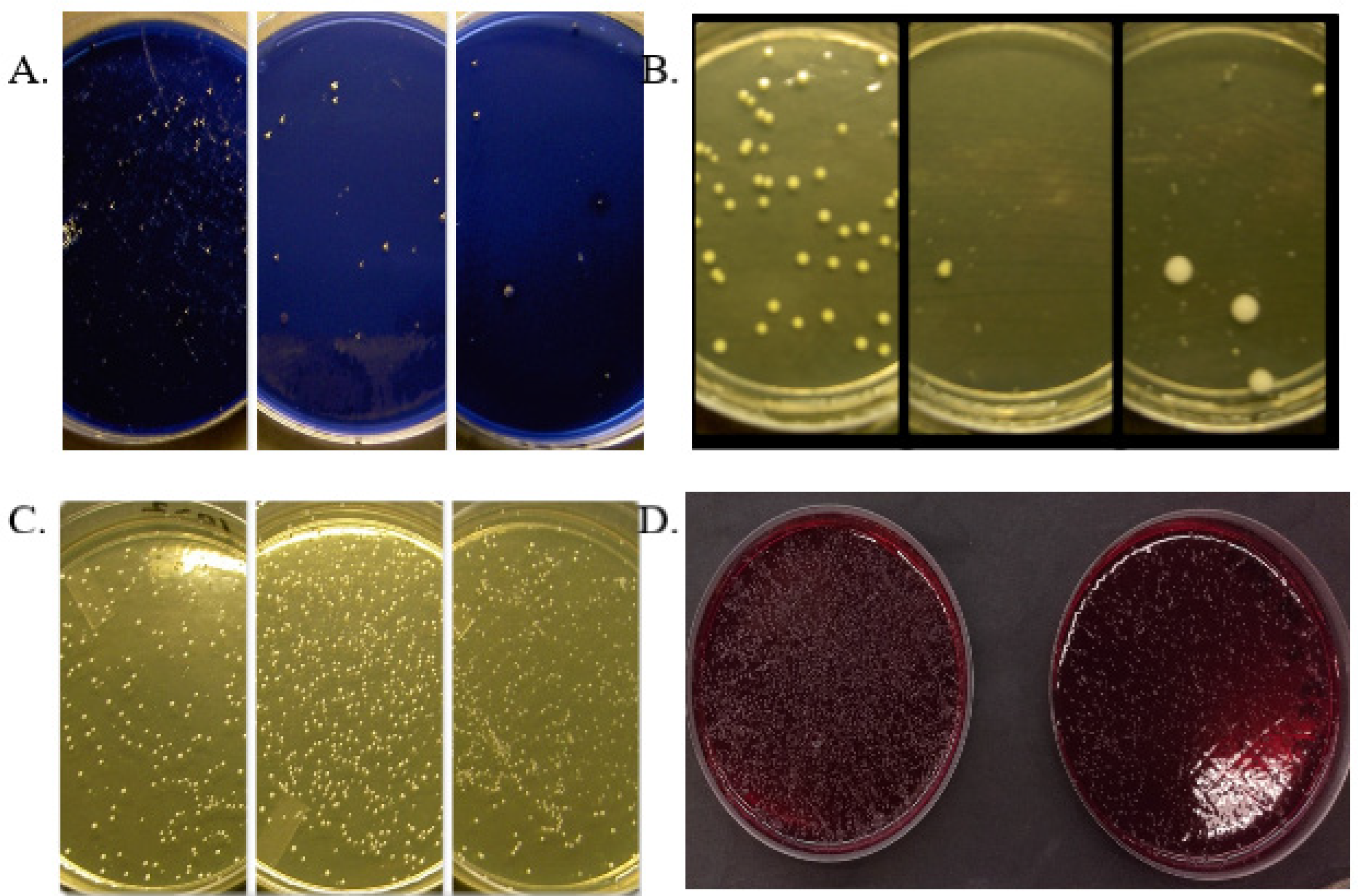

Effects of Fermented Lingonberry Juice on Oral Microbes

Old age and mouth-drying drugs affect the number of oral microbes: a dry mouth predisposes to caries, which can be seen in the results of

S. mutans smears as high values (

Figure 1A). After using the mouthwash, the levels of

S. mutans decrease significantly and the effect remains even afterwards (6 months) after the use of the mouthwash is stopped [

33]. Oral

Candida -yeast levels decrease significantly during the use of fermented lingonberry mouthwash (

Figure 1B) and it is also effective against non-

Candida albicans species such as

C. glabrata and

C. parapsilosis. The number of lactobacilli increase during mouthwash use (

Figure 1C). The changes in the amounts of

S. mutans,

Candida yeasts and lactobacilli remain long after the use of the mouthwash is stopped [

36]. The development of gingivitis, periodontitis, implant mucositis and peri- implantitis is a multifaceted process, in which home care of the mouth and regular professional cleaning of the mouth are of central importance, especially in the prevention and maintenance of the diseases concerned. Fermented lingonberry mouthwash significantly reduces periodontitis- related bleeding -on- probing (BOP) - and visible plaque index (VPI) indices [

33,

35,

36].

Figure 1D shows the clear growth-limiting effect of mouthwash on anaerobic bacteria in a clinical trial [

33].

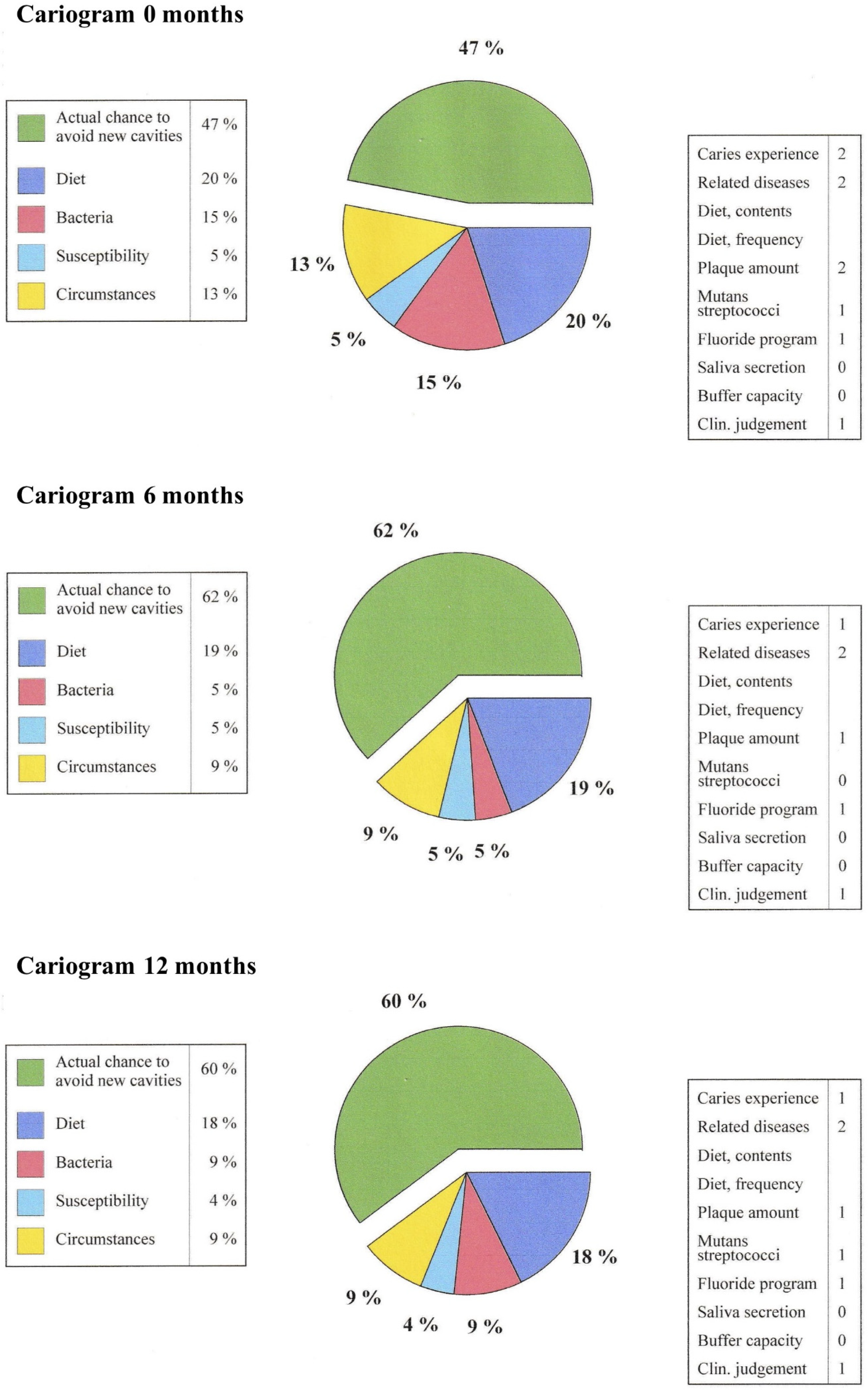

Fermented lingonberry juice significantly increases saliva secretion and improves the buffer capacity of saliva, but does not lower saliva pH, reduces the sensation of dry mouth, and significantly reduces

Candida - yeasts and

Streptococcus mutans bacteria. The amount of caries, low-grade inflammation of attachment tissues, gingival bleeding and the amount of plaque also decreases significantly [

33,

35,

36]. Caries risk can be assessed using a cariogram (Cariogram, Version 3.00) [

37]. The effect of different components on caries risk (36) can be seen in

Figure 2. The average data of the patient material (n= 25) on different parameters from the time points 0, 6 and 12 months have been entered into the cariogram program; the effect of the fermented lingonberry mouthwash can be seen in the reduction of caries risk (0–6 months) and the preservation of this caries protection for 6–12 months. Low-grade inflammation of the attachment tissues can be monitored by measuring the concentration of active matrix metalloprotease-8 (aMMP-8) in a mouthwash sample [

38]. Fermented lingonberry juice reduces low-grade inflammation and is anti-inflammatory [

35,

36,

39]. aMMP-8 levels can also be measured when investigating the level of low-grade inflammation in common diseases, such as pre-diabetes screenings at the dentist’s office [

40], and COVID-19 as a risk disease [

41].

Summary

Based on the literature, lingonberries have a versatile, beneficial effect on general health and oral health. Particularly fermented foods have been found to be anti-inflammatory. Based on various studies, lingonberries may have a beneficial antioxidant effect in cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammation, obesity and diabetes, as well as inhibition of the growth of oral and intestinal microbes. They may also prevent the growth or invasion of cancer cells. Based on in vivo studies, lingonberries have been found to have a stabilizing effect on blood sugar, insulin secretion and post-meal levels of free fatty acids. In the oral area, the increase in saliva secretion and the buffer capacity of saliva, the inhibition of the growth of opportunistic microbes, the reduction of low-grade inflammation and the reduction of plaque and gingival bleeding with fermented lingonberry juice have been found to reduce the risk of gum disease and caries. However, more clinical studies are needed to provide evidence of the versatile, beneficial effects of lingonberry phenolic substances on health.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing and reviewing of this manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by Helsinki Research Foundation TYH2022225.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this article to the memory of professor, senior physician Annamari Ranki, who passed away during our study of fermented lingonberry juice mouthwash in APECED patients (31).

Conflicts of Interest

The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kylli, P.; Nohynek, L.; Puupponen-Pimiä, R.; Westerlund-Wikström, B.; Leppänen, T.; Welling, J.; Moilanen, E.; Heinonen, M. Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) and European cranberry (Vaccinium microcarpon) proanthocyanidins: isolation, identification, and bioactivities. J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59, 3373–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehtonen, H.M.; Rantala, M.; Suomela, J.P.; Viitanen, M.; Kallio, H. Urinary excretion of the main anthocyanin in lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea), cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, and its metabolites. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 4447–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E. M.; Nitecki, S.; Pereira-Caro, G.; McDougall, G. J.; Stewart, D.; Rowland, I.; Crozier, A.; Gill, C. I. Comparison of in vivo and in vitro digestion on polyphenol composition in lingonberries: potential impact on colonic health. BioFactors (Oxford, England) 2014, 40, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laitinen, L. A.; Tammela, P. S.; Galkin, A.; Vuorela, H. J.; Marvola, M. L.; Vuorela, P. M. Effects of extracts of commonly consumed food supplements and food fractions on the permeability of drugs across Caco-2 cell monolayers. Pharm Res 2004, 21, 1904–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Meo, F.; Valentino, A.; Petillo, O.; Peluso, G.; Filosa, S.; Crispi, S. Bioactive Polyphenols and Neuromodulation: Molecular Mechanisms in Neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, M. Antioxidant activity and Antimicrobial effect of berry phenolics – a Finnish perspective. Mol Nutr. Food Res 2007, 51, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ames, B.N.; Shigenaga, M.K.; Hagen, T.M. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90, 7915–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.Y.; Feng, R.; Bowman, L.; Penhallegon, R.; Ding, M.; Lu, Y. Antioxidant activity in lingonberries (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) and its inhibitory effect on Activator protein-1, nuclear factor-kappaB, and mitogen- activated protein kinases activation. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 3156–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Määttä-Riihinen, K.R; Kähkönen, M.P.; Törrönen, A.R.; Heinonen, I.M. Catechins and procyanidins in berries of Vaccinium species and their antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 8485–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoornstra, D.; Vesterlin, J.; Pärnänen, P.; Al-Samadi, A.; Zlotogorski -Hurvitz, A.; Vered, M.; Salo, T. Fermented lingonberry juice inhibits oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma invasion in vitro similarly to curcumin. In Vivo 2018, 32, 1089–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, M.E.; Gustavsson, K.E.; Andersson, S.; Nilsson, A.; Duan, R.D. Inhibition of cancer cell proliferation in vitro by fruit and berry extracts and correlations with antioxidant levels. J Agric Food Chem 2004, 52, 7264–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, G.J.; Ross, H.A.; Ikeji, M.; Stewart, D. Berry extracts exert different antiproliferative effects against cervical and colon cancer cells grown in vitro. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 3016–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, J.R. Cold-field fruit extracts exert different antioxidant and antiproliferative activities in vitro. Food Chem 2011, 129, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minker, C.; Duban, L.; Karas, D.; Järvinen, P.; Lobstein, A.; Muller, C.D. Impact of Procyanidins from Different Berries on Caspase 8 Activation in Colon Cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015:154164. [CrossRef]

- Vilkickyte, G.; Raudone, L.; Petrikaite, V. Phenolic Fractions from Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities Assessment. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, G.T.T.; Nguyen, T.K.Y.; Kase, E.T.; Tadesse, M.; Barsett, H.; Wangensteen, H. Enhanced Glucose Uptake in Human Liver Cells and Inhibition of Carbohydrate Hydrolyzing Enzymes by Nordic Berry Extracts. Molecules 2017, 22, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalska, K.; Dembczyński, R.; Gołąbek, A.; Olkowicz, M.; Olejnik, A. ROS Modulating Effects of Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) Polyphenols on Obese Adipocyte Hypertrophy and Vascular Endothelial Dysfunction. Nutrients 2021, 13, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, L.P.; Harris, C.S.; Saleem, A.; Cuerrier, A.; Haddad, P. S.; Martineau, L. C.; Bennett, S. A.; Arnason, J. T. Inhibitory effect of the Cree traditional medicine wiishichimanaanh (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) on advanced glycation endproduct formation: identification of active principles. Phytother Res 2010, 24, 741–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryyti, R.; Hämäläinen, M.; Leppänen, T.; Peltola, R.; Moilanen, E. Phenolic Compounds Known to Be Present in Lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L.) Enhance Macrophage Polarization towards the Anti-Inflammatory M2 Phenotype. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, S.; Lomis, N.; Kahouli, I.; Dia, S.Y.; Singh, S.P.; Prakash, S. Microbiome, probiotics and neurodegenerative diseases: deciphering the gut brain axis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017, 74, 3769–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortaz, E.; Adcock, I.M.; Folkerts, G.; Barnes, P.J.; Paul Vos, A.; Garssen, J. Probiotics in the management of lung diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2013, 2013: 751068. [CrossRef]

- Puupponen-Pimiä, R.; Nohynek, L.; Meier, C.; Kähkönen, M.; Heinonen, M.; Hopia, A.; Oksman- Caldentey, K.M. Antimicrobial properties of phenolic compounds from berries. J Appl Microbiol 2001, 90, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puupponen-Pimiä, R.; Nohynek, L.; Hartmann-Schmidlin, S.; Kähkönen, M.; Heinonen, M.; Määttä-Riihinen, K.; Oksman Caldentey, K.M. Berry phenolics selectively inhibit the growth of intestinal pathogens. J Appl Microbiol 2005, 98, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toivanen, M.; Huttunen, S.; Lapinjoki, S.; Tikkanen- Kaukanen, C. Inhibition of adhesion of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial cells by berry juice polyphenolic fractions. Phytother Res 2011, 25, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokubu, E.; Kinoshita, E.; Ishihara, K. Inhibitory Effects of Lingonberry Extract on Oral Streptococcal Biofilm Formation and Bioactivity. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll 2019, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärnänen, P.; Lähteenmäki, H.; Tervahartiala, T.; Räisänen, I.T.; Sorsa, T. Lingonberries-General and Oral Effects on the Microbiome and Inflammation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaeva-Glomb, L.; Mukova, L.; Nikolova, N.; Badjakov, I.; Dincheva, I.; Kondakova, V.; Doumanova, L.; Galabov, A. S. In vitro antiviral activity of a series of wild berry fruit extracts against representatives of Picorna -, Orthomyxo - and Paramyxoviridae. Nat Prod Commun 2014, 9, 51–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Törrönen, R.; Kolehmainen, M.; Sarkkinen, E.; Mykkänen, H.; Niskanen, L. Postprandial glucose, insulin, and free fatty acid responses to sucrose consumed with blackcurrants and lingonberries in healthy women. Am J Clin Nutr 2012, 96, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törrönen, R.; Kolehmainen, M.; Sarkkinen, E.; Poutanen, K.; Mykkänen, H.; Niskanen, L. Berries reduce postprandial Insulin Responses to wheat and Rye breads in healthy women. J Nutr 2013, 143, 430–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, E.; Zimmermann, B.F.; Jungfer, E.; Chrubasik -Hausmann, S. Prevention of urinary tract infections with Vaccinium products. Phytother Res 2014, 28, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärnänen, P.; Suojanen, J.; Laine, M.; Sorsa, T.; Ranki, A. Long-term remission of candidiasis with fermented lingonberry mouth rinse in an adult patient with APECED. Int J Infect Dis 2024, 144, 107066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainionpää, A.; Tuomi, J.; Kantola, S.; Anttonen, V. Neonatal thrush of newborns: Oral candidiasis? Clin Exp Dent Res 2019, 5, 580–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärnänen, P.; Nikula-Ijäs, P.; Sorsa, T. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory lingonberry mouthwash- a clinical pilot study in the oral cavity. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärnänen, P.; Lomu, S.; Räisänen, I.T.; Tervahartiala, T.; Sorsa, T. Effects of Fermented Lingonberry Juice Mouthwash on Salivary Parameters—A One-Year Prospective Human Intervention Study. Dent J (Basel) 2022, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lähteenmäki, H.; Tervahartiala, T.; Räisänen, I.T.; Pärnänen, P.; Sorsa, T. Fermented lingonberry juice’s effects on active MMP-8 (aMMP-8), bleeding on probing (BOP), and visible plaque index (VPI) in dental implants- A clinical pilot mouthwash study. Clin Exp Dent Res 2022, 8, 1322–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pärnänen, P.; Lomu, S.; Räisänen, I.T.; Tervahartiala, T.; Sorsa, T. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory oral effects of fermented lingonberry juice- a one-year prospective human intervention study. Eur J Dent 2023, 17, 1235–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratthall, D.; Hänsel Petersson, G. Cariogram --a multifactorial risk assessment model for a multifactorial disease. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005, 33, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorsa, T.; Räisänen, I.; Gupta, S.; Tervahartiala, T.; Garlo, N.; Mäkitie, A.; Pätilä, T. Finnish dental innovations enable rapid diagnosis of gum disease and plaque control. The healing power of medicine - 100 science stories from cells to applications. Anne Pitkäranta, Kaija-Leena Kolho, Kimmo Kontula (ed.) Duodecim, 1st edition 2024, 152–154.

- Berries United’s lingonberry mouthwash is effective against yeast, plaque, bacteria and oral tissue-destructive enzymes. Br Dent J. [CrossRef]

- Grigoriadis, A.; Räisänen, I.T.; Pärnänen, P.; Tervahartiala, T.; Sorsa, T.; Sakellari, D. Prediabetes/diabetes screening strategy at the periodontal clinic. Clin Exp Dent Res 2021, 7, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S; Saarikko, M.; Pfützner, A.; Räisänen, I.T.; Sorsa, T. Compromised periodontal status could increase mortality for patients with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 314. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).