1. Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a dysfunctional immune disorder characterized by an excessive activation of macrophages and lymphocytes and an overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in systemic inflammation and tissue damages [

1,

2]. Two main forms of HLH are known: primary HLH, usually related to genetic disorders, and acquired HLH, which is secondary to other diseases such as neoplasms (mainly haematological), autoimmune disorders or infectious diseases. Most common infectious causes are viruses like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [

3]. Tuberculosis (TB) is a communicable disease with a great burden of morbidity and mortality especially in low and middle-income countries; according to the World Health Organization, 7.5 million people were newly diagnosed with TB in 2022 with 1.3 million deaths worldwide [

4]. Italy is a low TB burden country with an estimated incidence of 4.1 per 100,000 people in 2021; about 57% of cases are diagnosed in non-native people, mainly migrants from highly endemic countries [

5]. Active TB is an uncommon cause of HLH, causing 9-25% of HLH secondary to infections cases [

2]. Here we report a case of HLH associated with miliary TB (MTB) in an apparently immunocompetent healthy man.

2. Detailed Case Description

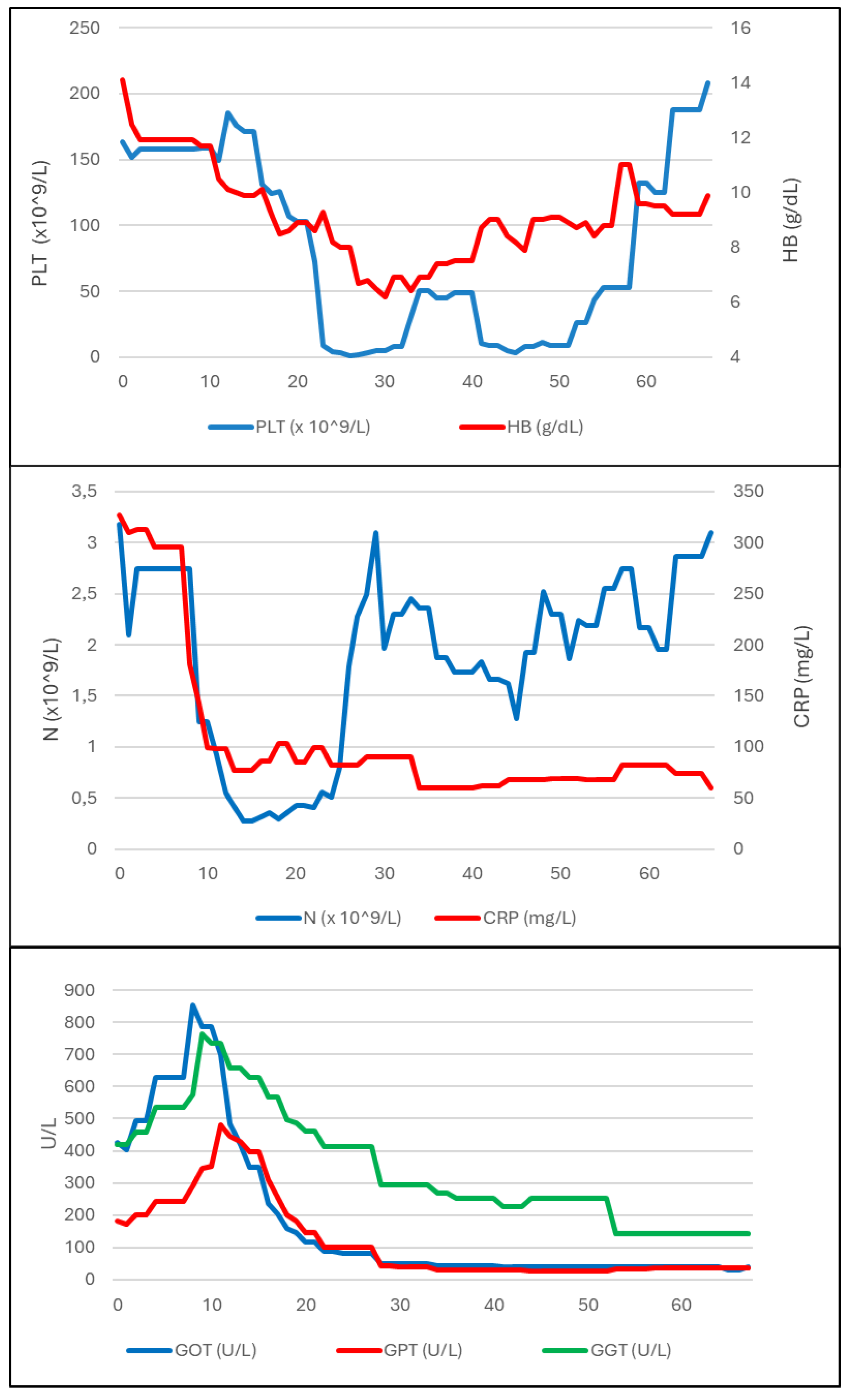

The patient was a healthy 26-year-old man born in Gambia (Western Africa) and had lived in Italy since 2017. He presented to the Emergency Department (ED) of S. Jacopo Hospital in Pistoia, Italy, at the end of August 2022 with fever and history of about five kg weight loss in the previous weeks; chest X-ray (CXR) resulted normal and blood tests (BT) evidenced mild leukopenia and increase of C-reactive protein (CRP). He was discharged home with antipyretic therapy. Due to persistence of symptoms, he returned to the same ED after three weeks: CXR was repeated with evidence of multiple pulmonary micronodules and BT showed persistent leukopenia (white blood cells, WBC, 3.7 x 10^9 cells/L) and increased inflammation indexes (CRP 320 mg/L with normal value <5 mg/L, procalcitonin, PCT, 24 ng/mL with normal value < 0.5 ng/mL, ferritin >7500 ng/mL with normal value 30-400 ng/mL) and cholestasis indexes (gamma glutamyl transferase, GGT, 420 U/L, total bilirubin, BLR, 2.5 mg/dL). Therefore, he was admitted to the Infectious Diseases Department on 15 September 2022.

On clinical examination he was alert and oriented, eupneic and pyretic. He had a mild scleral jaundice, palpable neck lymphadenopathies, tense abdomen and splenomegaly. On suspicion of bacterial infection, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin was initially started (days 1-5 of hospitalisation); several microbiological tests, including HIV test, were performed and resulted negative, while interferon gamma release assay (IGRA, QuantiFERON-TB) resulted repeatedly indeterminate. A chest-abdomen computed tomography (CT) evidenced pulmonary micro-nodularities and multiple lymphadenopathies at thoracic, abdominal, supraclavicular, and latero-cervical levels, associated with splenomegaly (15.5 cm); on suspicion of TB, sputum and bronchial aspirate (BA) with microbiological tests for mycobacteria were performed. Additionally, due to blurred vision in left eye, an ophthalmologic examination with fluorescein angiography raised the suspicion of choroidal tuberculoma.

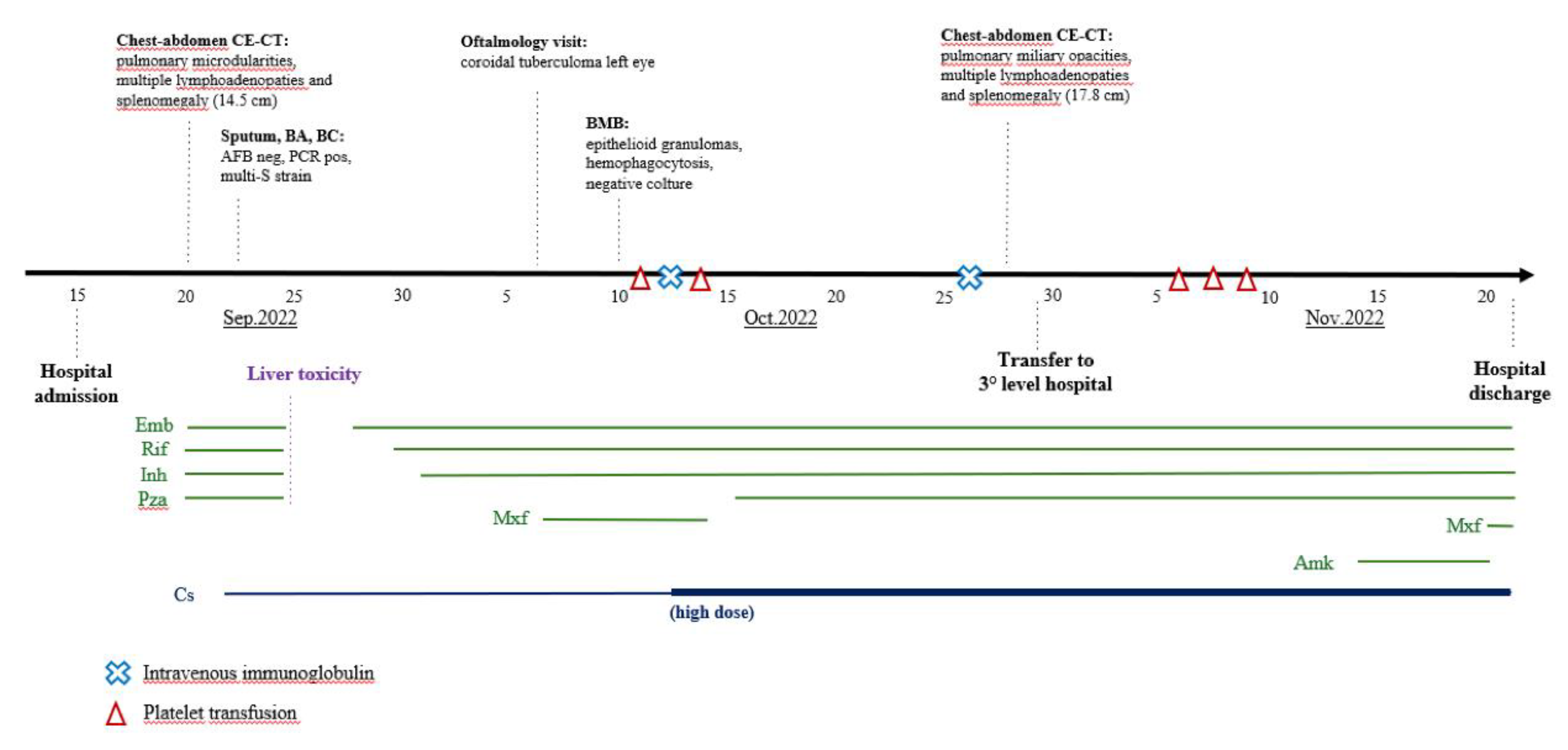

On seventh day after admission, with the positive result on sputum and BA of polymerase-chain reaction (PCR) for M. tuberculosis complex with no evidence of rifampicin resistance mutations, we started four-drug antitubercular therapy (ATT) with rifampin (RIF), isoniazid (INH), pyrazinamide (PZA) and ethambutol (EMB). Examination for acid-fast bacilli was negative, and culture exam on the same samples resulted positive for M. tuberculosis with a total sensitivity to first-line TB drugs. Moreover, blood cultures were positive for M. tuberculosis, while PCR for M. tuberculosis complex on stool and urine resulted negative. Together with ATT, steroid therapy (CS, prednisone 25 mg/day) was started. However, anti-TB drugs were discontinued after 5 days due to a further increase of hepatic cytolysis (up to 700 U/L of glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, GPT) and cholestasis indexes (GGT up to 700 U/L, BLR 8 mg/dL). Following a 48-hours of wash-out, ATT was gradually reintroduced by replacing PZA with moxifloxacin (MXF) due to its lower hepatotoxicity and better ocular penetration; subsequently, transaminases and cholestasis indexes gradually decreased.

Figure 1 shows a summary of the diagnostic and microbiological tests and treatments administered. The development of biochemical parameters during the disease course is summarized in

Figure 2.

In order to investigate the pancytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy (BMB) was performed on day 24 of hospitalisation. In the following days, platelet count (PLT) abruptly decreased with a persistently positive Coombs test; this was first attributed to an autoimmune and iatrogenic mechanism related to the introduction of MXF, which was therefore discontinued. However, PLT and haemoglobin (HB) counts further decreased (up to 1000 cells/mL and 6.7 g/dL, respectively), so PLT transfusion, therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG, 1 mg/kg/day, days 27-28 of hospitalisation) and high-dose CS (dexamethasone 40 mg/day from day 27) were started.

In subsequent days a clinical improvement was observed, together with normalisation of temperature, decreased ferritin trend and slight increase in PLT and HB count. Histologic examination on BMB showed Langhans-type multinucleated giant cells, epithelioid granulomas, and macrophage activation with aspects of hemophagocytosis. Microbiological culture on BMB was negative for

M. tuberculosis. At this time, patient presented six of eight diagnostic criteria for HLH (fever, splenomegaly, trilinear cytopenia, hyperferritinemia, bone marrow hemophagocytosis and decline of natural killer, NK, cells) [

3] and the diagnosis of HLH secondary to MTB was raised. Therefore, HLH treatment protocol [

3] was applied (dexamethasone 10 mg/m2/day from day 33 of hospitalisation) and PZA was reintroduced as fourth antitubercular drug to ensure adequate treatment of the underlying disease.

Due to ongoing thrombocytopenia, on day 37 the patient was transferred to a tertiary level hospital (Careggi University Hospital of Florence, Italy) where TB therapy was implemented with intravenous amikacin (from day 48) and CS therapy was confirmed, with a gradual improvement of clinical and biochemical parameters. Therefore, in agreement with immunology and haematology specialists, immunosuppressive therapy was not escalated, given the concomitant multi-organ infectious disease and the hypothesis of autoimmune activation (IRIS-like) after TB therapy beginning. The patient was discharged after 62 total days of hospitalisation in good clinical condition with ATT (RIF-INH-EMB-MXF) and CS (prednisone 50 mg/day in tapering regimen) treatment.

After discharge, the patient continued ATT and CS treatment with regular follow-up visits and good clinical course. Blood counts and hepatic function indexes were persistently within normal range, even after CS therapy discontinuation at ninety days after discharge. Immunophenotype on peripheral blood evidenced a reduction of interferon-gamma production by NK cells. Total body CT performed three months after treatment beginning showed reduction of pulmonary micronodularities, abdominal lymphadenopathies and splenomegaly. Patient’s condition continuously improved and ATT was discontinued after a total of twelve months.

3. Discussion

Secondary HLH is a serious haematologic condition triggered by an immune hyperactivation in response to various antigenic challenges, including autoimmune diseases, persistent infections, and malignancies [

1]. Most common infectious agents associated with HLH are EBV, Cytomegalovirus, HIV and most recently SARS-CoV-2 among viruses, Leishmania among protozoans, Rickettsiae and Mycobacteria among bacteria. These infections can trigger an hyperactivation of macrophages and CD8+ T lymphocytes with an overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines [

6,

7,

8]. To the best of our knowledge, two systematic reviews were recently published about association between TB and HLH; most of the cases described involve immunocompromised patients and the mortality rate is higher when diagnosis and treatment are delayed [

2,

9].

According to Kurver

et al., a big proportion of patients with TB-triggered HLH have extrapulmonary localizations of TB, with a high percentage of bone marrow involvement [

9]. In our patient,

M. tuberculosis was isolated from respiratory specimens and blood cultures; there was also evidence of eye involvement, although a microbiological confirmation from this site was not feasible. Bone marrow biopsy showed a histological pattern consistent with TB, but

M. tuberculosis was not isolated.

Consistently with our case, most patients with TB-associated HLH show anergy, defined by the absence of interferon-γ–mediated T-cell memory [

9]; this suggests that a failure in controlling the infection, as evidenced by the high number of disseminated forms, may stimulate the immune hyperactivation that contributes to HLH development.

Diagnosis of HLH is based on criteria applied in the HLH-2004 [

3]. Our patient fulfilled six out of eight criteria (namely fever, splenomegaly, trilinear cytopenia, hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, reduction of NK-cells and hyperferritineamia); level of soluble CD25 was not assessed because it was not performed by our laboratory.

Tuberculosis associated HLH diagnosis can be challenging because HLH and MTB have several non-specific, overlapping characteristics, particularly fever, splenomegaly and anaemia; thrombocytopenia and markedly increase in ferritin levels are less common in TB but can still be observed [

6]

. In our case, the rapid drop in PLT count was not attributed to TB and prompted further evaluation which led to HLH diagnosis.

Treatment of HLH is described in 2004 guidelines [

3] and it is based on high dose CS, IVIG and immunosuppressive drugs like cyclosporin and etoposide in refractory cases. Nevertheless, in TB-HLH, a prompt start of ATT is of paramount importance: in studies by Fauchald and Kurver, mortality rate was 100% in patients who did not receive ATT, suggesting that removal of mycobacterial antigenic drivers is crucial to interrupt immune hyperactivation [

2,

9].

Our patient developed HLH when TB diagnosis had already been established and he was already on ATT, while at the hospital admission HLH criteria were not fulfilled. There are reports of patients who developed TB-HLH during ATT as a paradoxical reaction (PR) [

9]. PR are defined as the worsening of pre-existing tuberculous lesions or the appearance of new lesions in patients whose clinical symptoms initially improved with ATT and, although their pathogenesis is not well established, may be linked to the release of mycobacterial antigens during the destruction of infected macrophages [

10]. In our case, the release of antigens due to the bactericidal effect of ATT may have furtherly stimulated immune system; nevertheless, given the inability to control the infection, this may have contributed to HLH development.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this case emphasizes that HLH should be considered in patients with MTB, especially with paradoxical worsening during ATT, as timely diagnosis and treatment are crucial to increase the chances of survival. Cytopenia and markedly increased levels of serum ferritin may help to distinguish TB-associated HLH from other conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.M., P.B. and A.B.; Methodology: J.M and C.F.; Resources: F.D., F.M., C.F., A.F.M. and D.M.; Data curation: F.D. and F.M; Writing—original draft preparation: F.D. and F.M.; Writing—review and editing: J.M.; Visualization: F.D. and F.M.; Supervision: P.B. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Allen, C. E.; Mcclain, K. L. Pathophysiology and Epidemiology of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015, 177, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauchald, T.; Blomberg, B.; Reikvam, H. Tuberculosis-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Review of Current Literature. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henter, J. I.; et al. . et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatric Blood and Cancer 2007, 48, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

WHO Global Tuberculosis Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Volume XLIX, ISBN 9789240013131.

- Tuberculosis surveillance and monitoring in Europe 2022–2024; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Trovik, L. H. et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and miliary tuberculosis in a previously healthy individual: a case report. J Med Case Rep, 2020, 14.

- Rouphael, N.G.; et al. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007, 12, 814–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerolle, N.; et al. Diversity and combinations of infectious agents in 38 adults with an infection-triggered reactive haemophagocytic syndrome: A multicenter study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2016, 22, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurver, L.; et al. Tuberculosis-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: diagnostic challenges and determinants of outcome. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geri, G.; et al. Paradoxical reactions during treatment of tuberculosis with extrapulmonary manifestations in HIV-negative patients. Infection 2013, 41, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).