1. Introduction

Despite renal cancer being a relatively infrequent neoplasia, its incidence has increased in the last decades [

1]. It is the urologic malignancy with worst prognosis, largely due to the incurability of metastatic disease [

2]. The excess mortality associated to COVID-19 pandemics has caused an apparent global cancer death rate decline, but the absolute number of cancer deaths increase due to both aging and population growth [

3,

4]. However, as with leukemia and melanoma, metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) is one of the malignancies with outstanding therapeutic advances that may also account for mortality reduction [

5].

The targeted therapy era of metastatic renal cancer started two decades ago along with the relatively recent advent of immunotherapy and immune-oncology (IO) combination therapy in the field, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have greatly contributed to the increased survival of this dreadful disease [

6]. In the absence of specific molecular markers, many prognostic factors have been evaluated and identified for mRCC. Most are inherent to the patient (Performance Status), tumor burden (cytoreductive nephrectomy, metastatic weight, biochemical and hematologic parameters) or treatment related (therapeutic response, disease-free interval, time from first diagnosis to development of metastatic disease and treatment tolerance and compliance) [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, the continuous therapeutic advances in the field have made difficult to universalize a prognostic model for all the different therapeutic scenarios. The risk stratification classification of International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) has been the major criteria used for the selection of treatment during the last decade. Under this schema antiangiogenic agents tend to be primarily used in patients with more favorable prognosis whereas patients with intermediate or poor risk tend to be treated with combination of antiangiogenic agents and immunotherapy, targeting immune checkpoints inhibitors (ICIs) such as programmed cell death receptor (PD-1) or its ligand (PD-L1), or the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) receptor [

11]. However, this treatment approach is not without controversy and some of the most important trials upon which IO combinations were originally tested did not in fact show significant benefit in the good prognosis group [

12,

13,

14]. Consequently, TKI treatment continues to be used with a significant proportion of mRCC patients and sequential treatment with targeted agents is highly recommended despite uncertainty surrounding what is the best sequence of agents for clinical use. The goal of treatment for mRCC is to prolong survival while maintaining good quality of life, and in real-life clinical practice this determines the choice of second-line and later-line agents [

15]. Also, the access to treatment options widely varies among health systems [

16].

The objective of our study is to analyze the clinical and pathological variables that determine long-term survival in patients with clear-cell (CC) mRCC receiving sequential targeted therapy initiated by first-line VEGFR-targeted therapy in a real-world setting. Based on this data we developed a nomogram to predict survival that could also be useful to promote risk stratification and treatment planning and segregate patients at higher risk of death that may need more aggressive treatment combinations front-line. Besides, this analysis could help as reference data to search for and validate new markers of prognosis in these patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

This is a non-interventional retrospective-prospective cohort multicenter study including patients with CC mRCC treated in two tertiary reference centers (Cruces and Donostia University Hospitals, Basque Country, Spain) treated with first-line TKI from 2008 to 2018. The study protocol was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee (CEIm-Euskadi approval umber PI2015059X, approval date 4/6/2015). All patients had radical nephrectomy, thus confirming histopathological diagnosis of CC RCC. Metastases were diagnosed by imaging modalities, often confirmed by biopsy and sometimes surgical resection. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) stage were used for tumor classification at the time of nephrectomy.

All patients received at least 1 cycle (4 weeks) of VEGFR TKI (sunitinib, pazopanib or sorafenib) until progression or unresponsiveness. Response to therapy was assessed both with Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) and Morphology, Attenuation, Size, and Structure (MASS) criteria on the first contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) study after initiating therapy. Cases lost for follow-up were not eligible for the study and patients with a diagnosis of non-clear-cell mRCC were also excluded. Participation in clinical trials was not considered a reason for exclusion. Patients were followed until death or last follow-up (December 2022).

2.2. Assessments

Clinical characteristics of the patents were obtained from medical records and by revision of the histopathology laboratory archive. There was confirmation of histopathological data by two specialized pathologists (J.D. S-I. and J.I.L). Performance status (PS) was measured with the ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) PS scale. Age, gender, stage at initial diagnosis, date of nephrectomy, date of surgery of metastases, number and site of metastases, date of treatment initiation, International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) risk criteria at initiation of treatment, response according to RECIST and MASS criteria, time and reason of discontinuation, second- and third-line therapies used (also with response and length of each treatment), date of last follow-up or date of death. Cause of death was assessed individually for each patient by two independent observers (J.D. S-I. and D.L.). When disagreement existed regarding the cause of death, it was assigned by a third party (J.C.A.) according to the information provided in the clinical records. The effectiveness of treatment was analyzed based on the clinical and pathological criteria investigated. Safety was not evaluated in this study.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Clinical and pathological characteristics were described using descriptive analytics. Differences between groups were compared with the chi-x2 test for qualitative measures and Student’s t test for quantitative measures. Overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) were analyzed with the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox regression analysis for CSS was performed, including the prognostic factors significant in univariate analysis, to adjust for covariates. The significance value cut-off was p<0.05 for the results. A nomogram to predict CSS using the independent variables identified is proposed and internally validated by bootstrapping. Accuracy of the predictive model is provided [

17]. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Analysis System 9.4 (SASS Institute Inc., Cary, NY, USA) and the R Project for Statistical Computing (free software environment for statistical computing and graphics; version 3.5.0;

http://www.r-project.org).

3. Results

3.1. Patients Characteristics at the Time of Nephrectomy

A total of 170 patients with CC mRCC treated with sunitinib as first-line were considered for the study. However, 25 were ineligible either because response criteria could not be determined (n=5), histology was not consistent with diagnosis of CC (n=4) or lost to follow-up (n=16). Therefore, 145 patients were finally included into the study and followed until death or December 2022.

In this cohort, the male to female ratio was 2.5:1. Nephrectomy was performed in all patients. Median tumor size was 8 (IQR 4.6) cm. Fuhrman grade was 1 in 6 (4.1%), 2 in 29 (20%), 3 in 44 (30.4%) and 4 in 66 (45.5%). For AJCC T category 22 patients (15.2%) were pT1, 18 (12.4%) pT2, 96 (66.2%) pT3 and 9 (6.2%) pT4. At the time of nephrectomy NCCN Stage was I in 18 (12.4%), II in 10 (6.9%), III in 51 (35.2%) and IV in 66 (45.5%). Positive nodes were identified in 23 (15.9%) of cases with a single positive node (N1) in 15 (65.2%) and several (N2) in 8 (34.8%). Metastatic disease was present at the time of diagnosis in 59 (40.7%) patients, 15 (25%) with single and 44 (75%) with multiple metastasis. In 86 (59.3%) metachronous metastasis developed at a median 20 (IQR 42, range 1-201) months after nephrectomy. Metastases were pathologically confirmed in 32 cases (22%) and surgical resected in 12 (8.3%).

3.2. Patients Characteristics at Initiation of Treatment of mRCC

The median age of the patient at time of treatment was 60 (IQR 14, 95% CI 57.9-61.4) years. The ECOG scale and IMDC risk classification are depicted in

Table 1. Treatment was initiated in all cases after diagnosis of mRCC. Patients were followed for a median 48 (IQR 72; 95% CI 56-75.7) months after sunitinib initiation.

3.3. Response to First-Line Treatment

Table 2 presents the classification of response to VEGFR TKI at 3 months. At a median 17 ± 26.4 months, disease progression was confirmed in 129 patients (89%). At last follow-up 8 cases (5.5%) continued initial treatment. Reasons for discontinuation were 86 (59.3%) ineffectiveness, 33 (22.8%) intolerance, 12 (8.3%) death and 6 (4.1%) other reasons.

3.4. Other Treatments Received

Second-line therapy was used in 89 patients (59.3%) and consisted on small molecule TKI axitinib or multi-TKI cabozantinib (n=56), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors everolimus or temsirolimus (n=23) and ICIs nivolumab and/or ipilimumab (n=10). Third-line therapies were used in 30 patients (20%) and consisted on multi-TKI cabozantinib (n=11), mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus (n=7) and combination of ICIs plus TKI (pembrolizumab or avelumab plus axitinib) (n=12). Rechallenge with TKI as fourth-line was used in 9 patients (6.2%), all with duration of tumor control ≥ 6 months on first-line therapy.

3.5. Overall and Cancer-Specific Survival

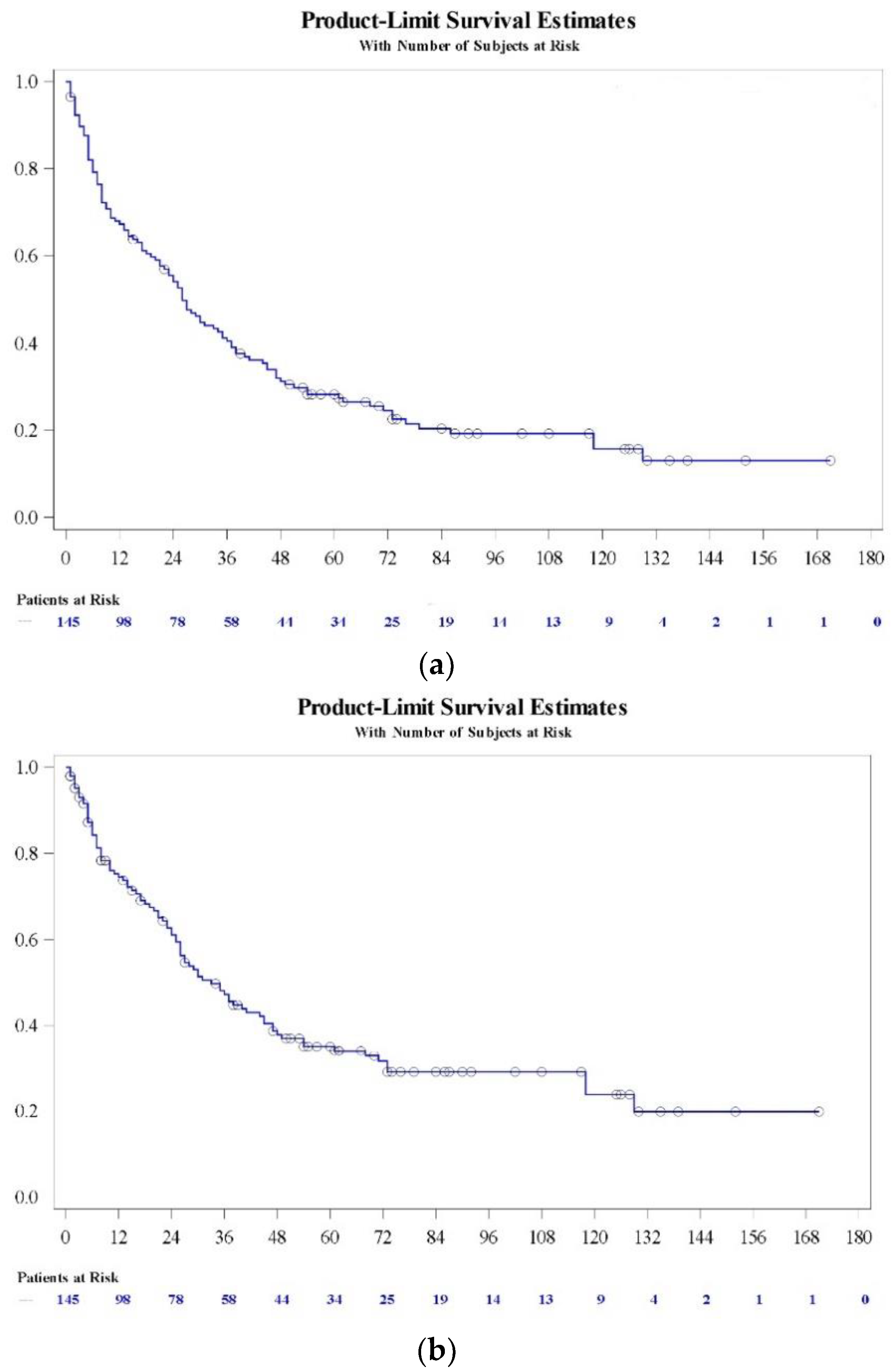

Survival (OS and CSS) at different times is presented in

Table 3 and in

Figure 1.

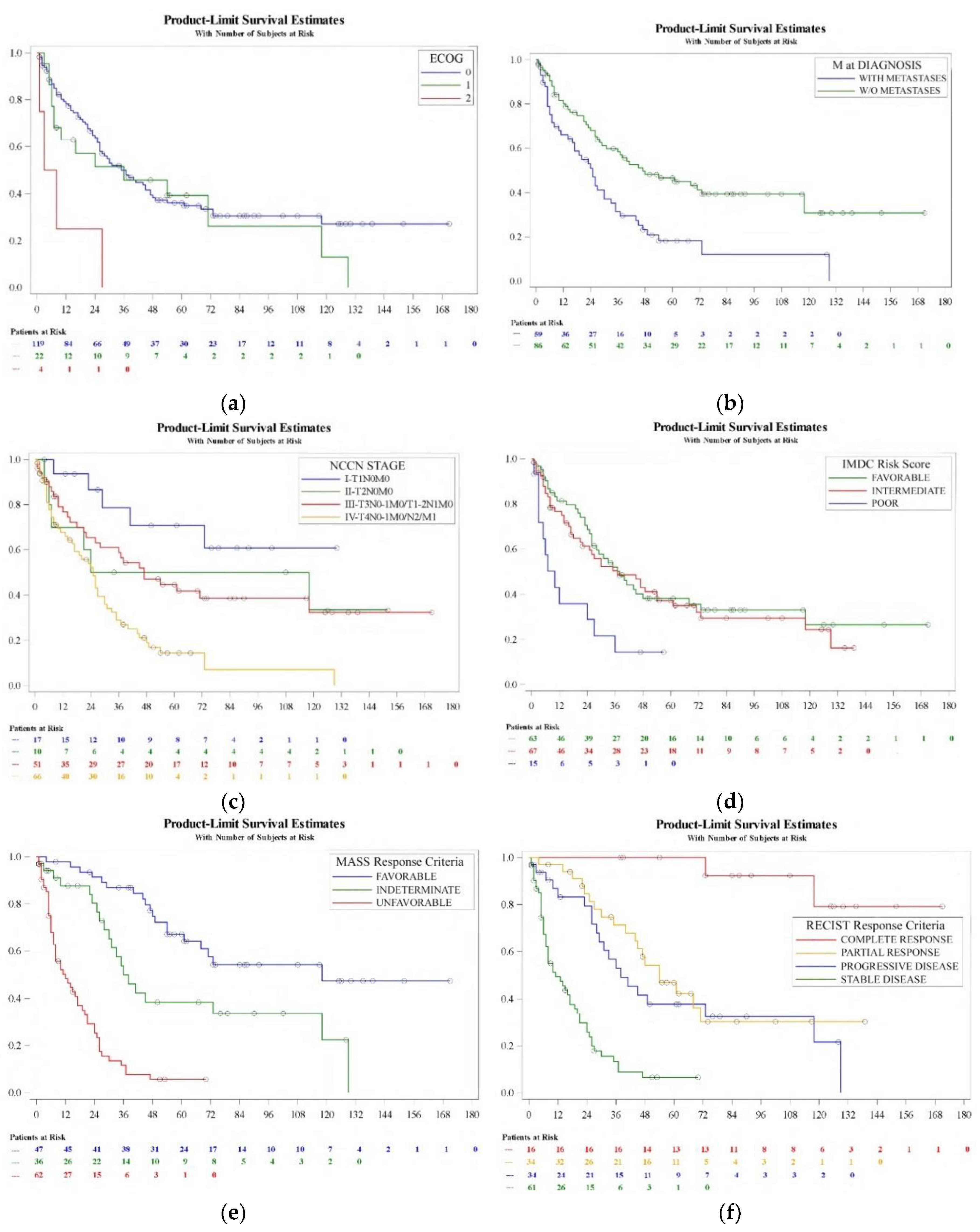

Kaplan-Meier analysis of CSS detected variables predicting prognosis include ECOG status (log-rank, p=0.004), metastasis at diagnosis (log-rank, p=0.0004), NCCN stage at diagnosis (log-rank, p=0.0001), IMDC risk classification at initiating treatment (log-rank, p=0.005), MASS response criteria (log-rank, p<0.0001) and RECIST response criteria (log-rank, p<0.0001) (

Figure 2). Patient age (log-rank, p=0.1), gender (log-rank, p=0.2) and pT category (log-rank, p=0.1), pN category (log-rank, p=0.09) and Fuhrman grade (log-rank, p=0.5) at the time of diagnosis were not determinants of prognosis in this series.

Table 4 shows the corresponding hazard ratios and confidence interval limits for each variable by univariate analysis. Patient age, ECOG performance status, synchronicity of metastases, NCC stage, IMDC risk group, MASS and RECIST response criteria at 3 months were significant (p<0.05). Multivariate analysis revealed ECOG performance status, (0-1 vs 2, HR 3.36 (95% C.I. 1.88-5.97); p=0.0004), RECIST of first-line therapy at 3 months (stable and partial response vs complete response, HR 7.1 (95% C.I. 1.58-31.99); progression vs complete response, HR7.46 (95% C.I. 1.07-52.07); p=0.008), MASS response criteria at 3 months (1 vs 3, HR 0.16 (95% C.I. 0.04-0.61); 2 vs 3, HR 0.25 (95% C.I. 0.07-0.9); p<0.0001) and IMDC risk group (poor vs favorable and intermediate, HR 2.09 (95% C.I. 1.07-4.07); p=0.028) stayed as independent factors (p<0.05) of CSS after TKI based sequential therapy.

3.6. Nomogram for the Prediction of Prognosis

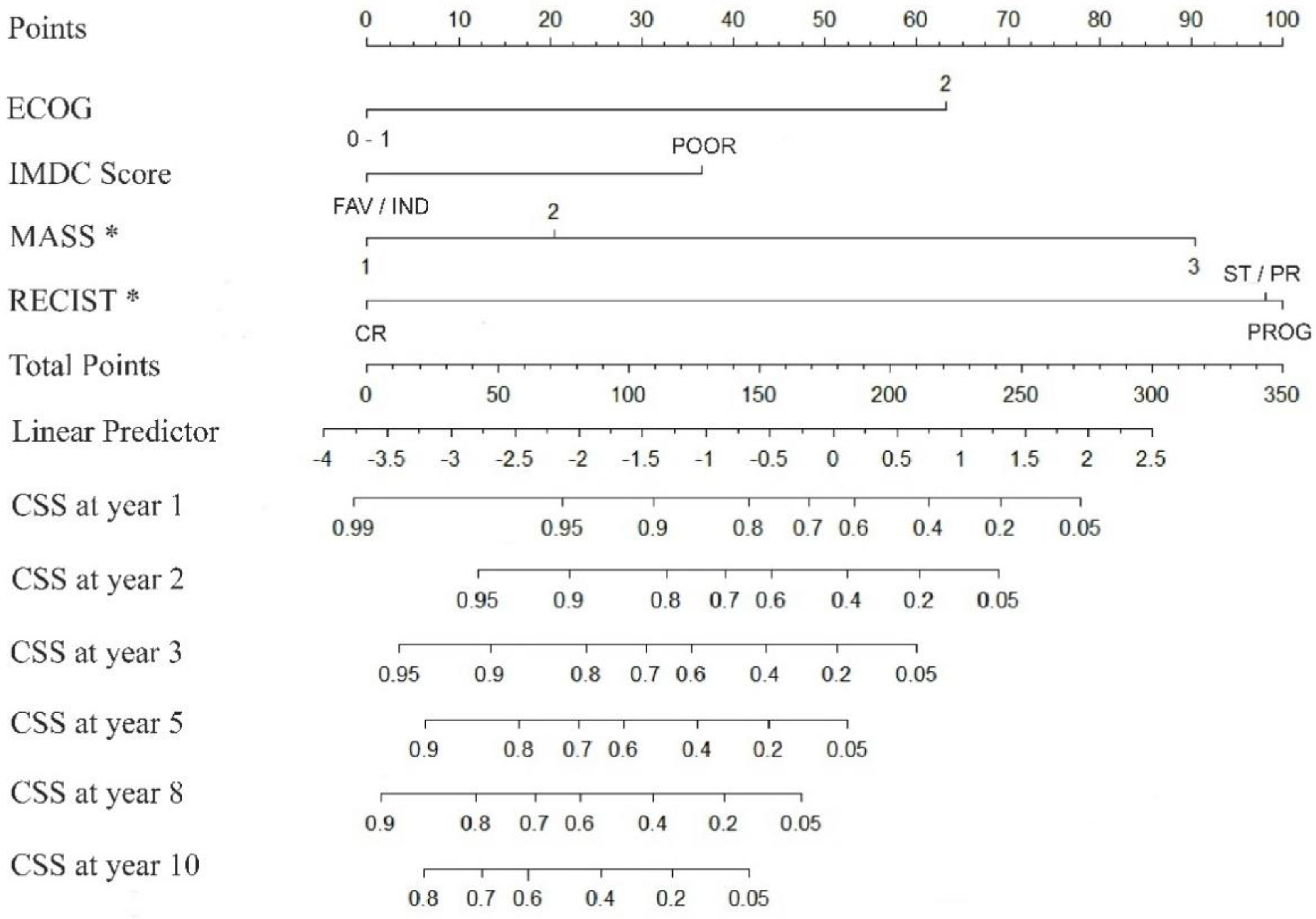

Using the multivariate Cox model presented, a nomogram-predicted 1 to 10 years CSS probability was generated (

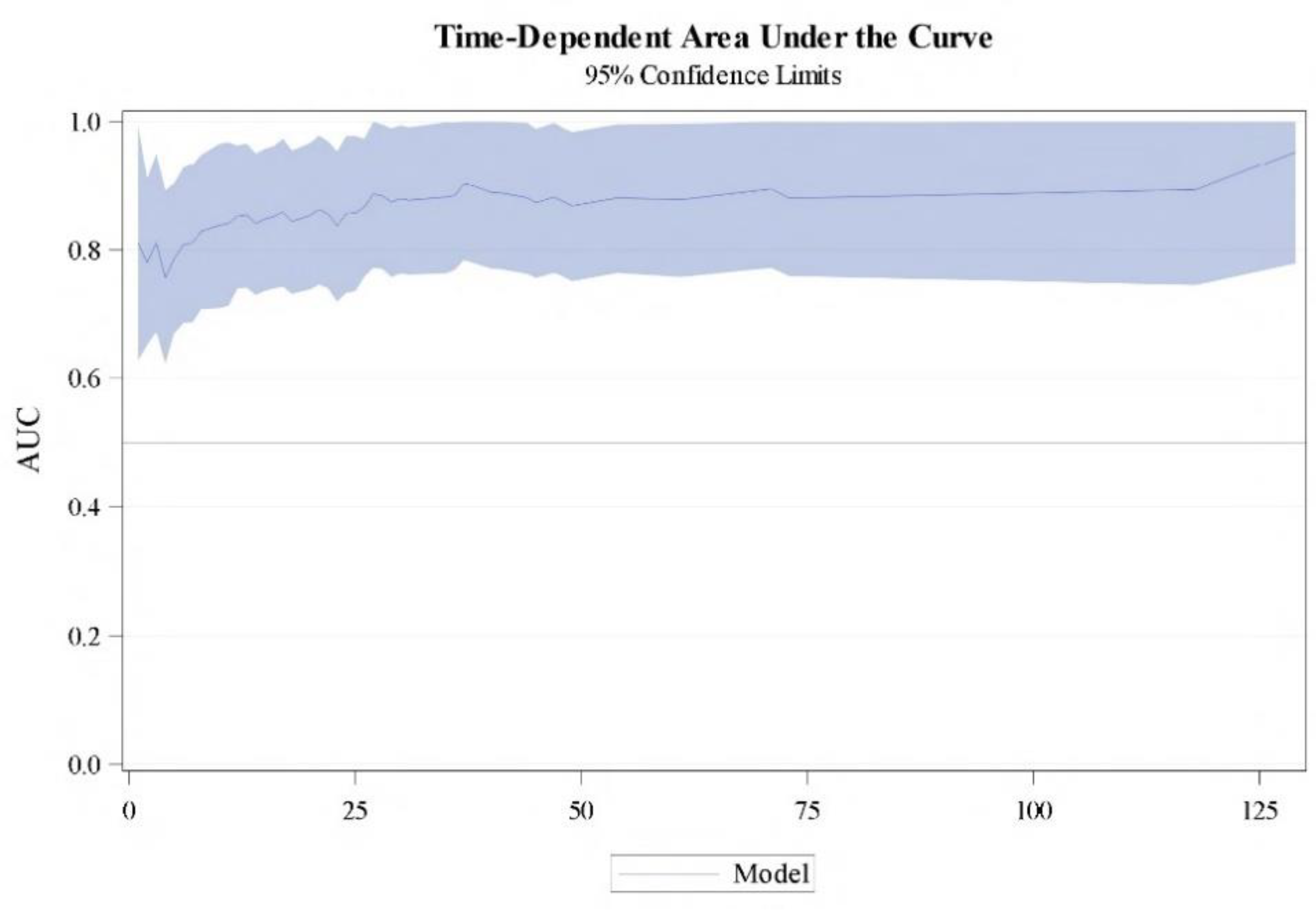

Figure 3). The model was internally validated using 500 bootstrap samples, the concordance was 0.778 (95% CI 73,3% - 81,6%). Time-dependent area under the curve (AUC) based on 50 perturbed samples is represented for CSS at different time of follow-up (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

The survival of mRCC patients has vastly improved since the advent of targeted therapy [

15]. In real-life setting VEGFR-targeted agents such as sunitinib, sorafenib and pazopanib have been widely used in the last two decades. Axitinib and cabozantinib, often considered after the failure of sunitinib, have also consolidated the sequential use of TKI based treatment. Everolimus and, more recently, nivolumab have been used after disease progression with first-line sunitinib or pazopanib as well [

16]. Prolonged survival of patients with mRCC who received sequential targeted agents has been demonstrated in many clinical trials, but the optimal sequences remain unidentified. However, clinical trials are not always representative of the real-life population [

18].

The landscape for sequential treatment of mRCC has become more diverse with the advent of immunotherapy, thus complicating the definition of the optimal treatment succession. However, several lessons have been learnt. On one hand, the benefit with ICI nivolumab after TKIs did not depend on the prior therapy, the number of antiangiogenic drugs used or the duration of response [

15]. On the other, the discovery and approval of ICIs has revolutionized management of mRCC and several ICI-based combinations have become the new standard of care for these patients [

11]. Options have expanded in recent years to include as standard first-line therapy the combinations of the IO agents ipilimumab and nivolumab, and VEGFR-targeted therapy with IO agents [

19]. Nonetheless monotherapy with antiangiogenic TKIs (e.g.,; pazopanib or sunitinib) still represents a first-line treatment option for selected patients in the favorable risk group according to the IMDC model and ICI monotherapy with the anti-PD-1 nivolumab is currently the main second-line option. For third line and subsequent therapies rechallenge a drug that previously achieved tumor control for 6 month or longer, and in cases in which treatment was stopped due to toxicity, is another alternative [

18].

Different combination therapies tend to be used for intermediate and poor risk groups. Both the heterogeneity of RCC and its constantly changing therapeutic scenario have complicated the establishment of prognostic markers [

20,

21]. Other continued controversies have also contributed to the undefinition, such as whether cytoreductive nephrectomy is valuable and/or how to optimize managements of adverse effects to minimize dose reduction and treatment discontinuation [

22,

23,

24]. To make matters worse, not all patients have access to novel immunotherapy-based combinations [

25].

We present a nomogram to predict long-term survival in patients with mRCC treated with first-line VGFR-TKI sunitinib, sorafenib or pazopanib and with successive treatment options including cabozantinib, everolimus or nivolumab. This graphic prediction tool takes into account factors that have an independent impact on outcome. They are ECOG status and IMDC risk score at the time of treatment initiation and both RECIST and MASS response criteria on the first CECT study performed after initiating therapy.

The IMDC prognostic model was also developed and validated in patients with mRCC receiving VEGF-TKIs based on six prognostic criteria: time from initial diagnosis to systemic therapy <1 year, Karnofsky performance status <80, serum hemoglobin, platelet count, absolute neutrophil count and corrected serum calcium [

10,

26]. Patients are characterized as having favorable (no criteria), intermediate (1-2 criteria), or poor (≥3 criteria) risk. It is widely admitted that the IMDC model provides essential information to guide treatment decisions and also predict the effectiveness of systemic therapy and prognosis [

16,

27]. There is an interesting discussion whether assessment of the therapeutic response in mRCC on CECT for changes in morphology, attenuation, size and structure according to MASS Citeria is more accurate than response assessment based on RECIST Criteria widely adopted by academic institutions, cooperative groups and in clinical trials [

28,

29]. Out study supports that both criteria are valid and complementary to assess treatment response, and also that a response to first-line VGFR-TKI has a clinical impact on CSS in the long-term [

30].

The main limitation of this model stands on the fact that it has been based on data from two institutions and external validation is advisable before it can be generalized. Additionally, variables such as the topography of metastases and TKI dose reduction or discontinuation due to adverse effects have not been considered and could have prognostic value [

24,

31]. Similarly, the number of patients who received fourth line or further therapies has not been considered. On the other hand, the main strength of the model is that it is based on simple measurements of clinical importance, such as patient status baseline (ECOG scale), risk category of metastatic disease before treatment (IMDC classification) and concise assessment of response after initiating therapy (RECIST and MASS criteria). These variables assessed baseline and on the first months of treatment initiation determine patient prognosis in the long-term. Durable complete response can be observed regardless of the prognostic group [

32]. Nephrectomy was always performed in these patients, and that could also be a limitation if this nomogram is used in a population of mRCC patients that do not receive nephrectomy. We cannot either assume the value of this model in patients receiving sequential treatment initiated with upfront immunotherapy [

33,

34]. This study serves to evaluate long-term survival of mRCC in the clinical practice and seems a good start point to investigate immunohistochemical and molecular makers predictive of prognosis in this series of patients.

5. Conclusions

VEGFR-TKI sequential therapy has greatly contributed to ameliorate survival of this uncurable disease in recent past and is still used today to some extent, especially in patients with presumed favorable prognosis. Hopefully the identification of prognostic biomarkers will allow a better selection of individualized therapy, given the many options available today. In the meantime, the nomogram here proposed may be a useful prognostic tool, at least for clinicians with patients initiating sunitinib or pazopanib as first line therapy. Baseline condition, IMDC risk classification and the evaluation of therapeutic response on first CECT study after initiating therapy using both RECIST and MASS criteria is a simple and reliable way to predict long-term prognosis.

Our experience favors the observation that sequential treatment with targeted agents improves survival of CC mRCC, and also that treatment should be continued until disease progression or even beyond in the targeted therapy era. However, it remains to be studied whether this nomogram could be used to promote immunotherapy or IO combination therapy after an initial course of VEGFR-TKI therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.A., G.L., C.H.L. and J.I.L.; methodology, J.C.A., G.L., D.L., A.M.I., J.D.S-I., J.F.D.; software, G.L. and J.F.D.; validation, J.C.A., G.L. and J.F.D.; formal analysis, G.L. and C.H.L.; investigation, J.C.A., G.L., D.L., A.M.I., J.D.S-I., C.H.L., J.F.D., C.M. and J.I.L.; resources, G.L. and C.H.L.; data curation, J.C.A., G.L., D.L., A.M.I., J.D.S-I., C.H.L., J.F.D., C.M. and J.I.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.A., G.L.; writing—review and editing, J.C.A., G.L., D.L., A.M.I., J.D.S-I., M.A., C.H.L., J.F.D., C.E.N-X., R.P., C.M. and J.I.L.; visualization, J.C.A. and G.L.; supervision, G.L., C.H.L. and J.I.L.; project administration, G.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. and C.H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basque Government (Elkartek KK-2024/00003). C.E.N-X. is funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (CP20/00008 and PI22/00386) (Spain, cofunded by the European Union).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee (Cem-Euskadi approval umber PI2015059X, approval date 4/6/2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Full data will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AJCC: American Joint-Committee on Cancer; AUC: area under the curve; CECT: contrast-enhanced computerized tomography; CI: Confidence Interval; CC: clear-cell; CSS: cancer-specific survival; CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HR: Hazard Ratio; ICI: immune checkpoints inhibitors; IMDC: International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium; IQR: interquartile range; IO: immune-oncology; MASS: Morphology, Attenuation, Size and Structure; mRCC: metastatic renal cell carcinoma; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; PD-1: programmed cell death receptor; PD-L1: programmed cell death receptor ligand; RECIST: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; OS: overall survival; PS: performance status; TKI: tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGFR: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, M.; Pezzicoli, G.; Tibollo, V.; Premoli, A.; Quaglini, S. Clinical outcome predictors for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective multicenter real-life case series. BMC Cancer. 2024, 24, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Cantero, G.; Longo, F.; Hernández-González, J.; Pueyo, Á.; Fernández-Aparicio, T.; Dorado, J.F.; Angulo, J.C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer diagnosis in Madrid (Spain) based on the RTMAD Tumor Registry (2019-2021). Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakopoulos, C.E.; Rini, B.J. Tyrrosine kinase inhibitors: Sorafenib, sunitinib, axitinib, and pazopanib. In Renal Cell Carcinoma. Molecular features and treatment updates; Editor Mototsugu Oya; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Mekhail, T.M.; Abou-Jawde, R.M.; Boumerhi, G.; Malhi, S.; Wood, L.; Elson, P.; Bukowski, R. Validation and extension of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering prognostic factors model for survival in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23, 832–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manola, J.; Royston, P.; Elson, P.; McCormack, J.B.; Mazumdar, M.; Négrier, S.; Escudier, B.; Eisen, T.; Dutcher, J.; Atkins, M.; Heng, D.Y.C.; Choueiri, T.K.; Motzer, R.; Bukowski, R. Prognostic model for survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results from the international kidney cancer working group. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 5443–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatorre, C.; Carter, G.C.; Chen, C.; Villarivera, C.; Zarotsky, V.; Cantrell, R.A.; Goetz, I.; Paczkowski, R.; Buesching, D. A comprehensive review of predictive and prognostic composite factors implicated in the heterogeneity of treatment response and outcome across disease areas. Int J Clin Pract. 2011, 65, 831–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, D.Y.; Xie, W.; Regan, M.M.; Harshman, L.C.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Vaishampayan, U.N.; Mackenzie, M.; Wood, L.; Donskov, F.; Tan, M.H.; Rha, S.Y.; Agarwal, N.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Rini, B.I.; Choueiri, T.K. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 141–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo, J.C.; Shapiro, O. The changing therapeutic landscape of metastatic renal cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019, 11, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; Vynnychenko, I.; Kryzhanivska, A.; Bondarenko, I.; Azevedo, S.J.; Borchiellini, D.; Szczylik, C.; Markus, M.; McDermott, R.S.; Bedke, J.; Tartas, S.; Chang, Y.H.; Tamada, S.; Shou, Q.; Perini, R.F.; Chen, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Powles, T. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.; Alekseev, B.; Rha, S.Y.; Porta, C.; Eto, M.; Powles, T.; Grünwald, V.; Hutson, T.E.; Kopyltsov, E.; Méndez-Vidal, M.J.; Kozlov, V.; Alyasova, A.; Hong, S.H.; Kapoor, A.; Alonso Gordoa, T.; Merchan, J.R.; Winquist, E.; Maroto, P.; Goh, J.C.; Kim, M.; Gurney, H.; Patel, V.; Peer, A.; Procopio, G.; Takagi, T.; Melichar, B.; Rolland, F.; De Giorgi, U.; Wong, S.; Bedke, J.; Schmidinger, M.; Dutcus, C.E.; Smith, A.D.; Dutta, L.; Mody, K.; Perini, R.F.; Xing, D.; Choueiri, T.K. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 1289–1300.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Powles, T.; Burotto, M.; Escudier, B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Zurawski, B.; Oyervides Juárez, V.M.; Hsieh, J.J.; Basso, U.; Shah, A.Y.; Suárez, C.; Hamzaj, A.; Goh, J.C.; Barrios, C.; Richardet, M.; Porta, C.; Kowalyszyn, R.; Feregrino, J.P. , Żołnierek, J.; Pook, D.; Kessler, E.R.; Tomita, Y.; Mizuno, R.; Bedke, J.; Zhang, J.; Maurer, M.A.; Simsek, B.; Ejzykowicz, F.; Schwab, G.M.; Apolo, A.B.; Motzer, R.J. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, E.; Schmidinger, M.; Heng, D.Y.C.; Grünwald, V.; Escudier, B. Improvement in survival end points of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma through sequential targeted therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016, 50, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesas, A.; Urbonas, V.; Tulyte, S.; Janciauskiene, R.; Liutkauskiene, S.; Grabauskyte, I.; Gaidamavicius, I. Sequential treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients after first-line vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy in a real-world setting: epidemiologic, noninterventional, retrospective-prospective cohort multicentre study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023, 149, 6979–6988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iasonos, A.; Schrag, D.; Raj, G.V.; Panageas, K.S. How to build and interpret a nomogram for cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26, 1364–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voog, E.; Campillo-Gimenez, B.; Elkouri, C.; Priou, F.; Rolland, F.; Laguerre, B.; Elhannani, C.; Merrer, J.; Pfister, C.; Sevin, E.; L’Haridon, T.; Hasbini, A.; Moise, L.; Le Rol, A.; Malhaire, J.P.; Delva, R.; Vauléon, E.; Cojocarasu, O.; Deguiral, P.; Cumin, I.; Cheneau, C.; Schlürmann, F.; Delecroix, V.; Boughalem, E.; Mollon, D.; Ligeza-Poisson, C.; Abadie-Lacourtoisie, S.; Monpetit, E.; Chatellier, T.; Desclos, H.; Coquan, E.; Joly, F.; Tessereau, J.Y.; Dupuy, S.; Lagadec, D.D.; Marhuenda, F.; Grudé, F. Long survival of patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Results of real ife study of 344 patients. Int J Cancer. 2020, 146, 1643–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Velasco, G.; Bex, A.; Albiges, L.; Powles, T.; Rini, B.I.; Motzer, R.J.; Heng, D.Y.C.; Escudier, B. Sequencing and combination of systemic therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol. 2019, 2, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, J.C.; Lawrie, C.H.; López, J.I. Sequential treatment of metastatic renal cancer in a complex evolving landscape. Ann Transl Med. 2019, 7 (Suppl 8), S272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterberg, E.; Iyer, S.; Nagar, S.P.; Davis, K.L.; Tannir, N.M. Real-world treatment patterns and clinical outcomes among patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2024, 22, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, D.H.; Park, I.; Ahn, J.H.; Lee, D.H.; You, D.; Jeong, I.G.; Song, C.; Hong, B.; Hong, J.H.; Ahn, H.; Lee, J.L. Long-term outcomes of tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016, 77, 339–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meagher, M.F.; Minervini, A.; Mir, M.C.; Cerrato, C.; Rebez, G.; Autorino, R.; Hampton, L.; Campi, R.; Kriegmair, M.; Linares, E.; Hevia, V.; Musquera, M.; D’Anna, M.; Roussel, E.; Albersen, M.; Pavan, N.; Claps, F.; Antonelli, A.; Marchioni, M.; Paksoy, N.; Erdem, S.; Derweesh, I.H. Does the timing of cytoreductive nephrectomy impact outcomes? Analysis of REMARCC registry data for patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor versus immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2024, 63, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnston, H.; Deal, A.M.; Morgan, K.P.; Patel, B.; Milowsky, M.I.; Rose, T.L. Dose intensity in real-world patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma taking vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2023, 21, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, Á.; Miranda, J.; Pertejo, A.; Álvarez-Maestro, M.; González-Peramato, P.; Aguilera, A.; García, E.; Trilla, L.; Gámez, Á.; Espinosa, E. Different outcomes among patients with intermediate-risk metastastic renal cell carcinoma treated with first-line tyrosine-kinase inhibitors. Clin Transl Oncol. 2024, 26, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heng, D.Y.; Xie, W.; Regan, M.M.; Warren, M.A.; Golshayan, A.R.; Sahi, C.; Eigl, B.J.; Ruether, J.D.; Cheng, T.; North, S.; Venner, P.; Knox, J.J.; Chi, K.N.; Kollmannsberger, C.; McDermott, D.F.; Oh, W.K.; Atkins, M.B.; Bukowski, R.M.; Rini, B.I.; Choueiri, T.K. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27, 5794–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, M.S.; Navani, V.; Wells, J.C.; Donskov, F.; Basappa, N.; Labaki, C.; Pal, S.K.; Meza, L.; Wood, L.A.; Ernst, D.S.; Szabados, B.; McKay, R.R.; Parnis, F.; Suarez, C.; Yuasa, T.; Lalani, A.K.; Alva, A.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Choueiri, T.K.; Heng, D.Y.C. Outcomes for International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic groups in contemporary first-line combination therapies for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2023, 84, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, J.L.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; Rubinstein, L.; Shankar, L.; Dodd, L.; Kaplan, R.; Lacombe, D.; Verweij, J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009; 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.D.; Shah, S.N.; Rini, B.I.; Lieber, M.L.; Remer, E.M. Morphology, Attenuation, Size, and Structure (MASS) criteria: assessing response and predicting clinical outcome in metastatic renal cell carcinoma on antiangiogenic targeted therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010, 194, 1470–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobu, R.; Numakura, K.; Naito, S.; Hatakeyama, S.; Kato, R.; Koguchi, T.; Kojima, T.; Kawasaki, Y.; Kandori, S.; Kawamura, S.; Arai, Y.; Ito, A.; Nishiyama, H.; Kojima, Y.; Obara, W.; Ohyama, C.; Tsuchiya, N.; Habuchi, T. Clinical impact of early response to first-line VEGFR-TKI in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma on survival: A multi-institutional retrospective study. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 4100–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, M.; De Giorgi, U.; Bimbatti, D.; Buti, S.; Procopio, G.; Sepe, P.; Santoni, M.; Galli, L.; Conca, R.; Doni, L.; Antonuzzo, L.; Roviello, G. Impact of metastatic site in favorable-risk renal cell carcinoma receiving sunitinib or pazopanib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2024, 22, 514–522.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Velasco, G.; Alonso-Gordoa, T.; Rodríguez-Vida, A.; Anguera, G.; Campayo, M.; Pinto, A.; Martínez Ortega, E.; Gallardo, E.; Fernández Núñez, N.; García-Carbonero, I.; Reig, O.; Méndez-Vidal, M.J.; Fernández-Calvo, O.; Vidal Cassinello, N.; Torregrosa, D.; López-Martín, A.; Rosero, A.; Valiente, P.G.; Garcías de España, C.; Climent, M.A.; Domenech Santasusana, M.; Rodríguez Sánchez, A.; Chirivella González, I.; Afonso, R.; García Del Muro, X.; Casinello, J.; Fernández-Parra, E.M.; García Sánchez, L.; Javier Afonso, J.; Hernando Polo, S.; Asensio, U. Long-term clinical outcomes of a Spanish cohort of metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients with a complete response to sunitinib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2023, 21, e166–e174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, Y.; Kojima, T.; Osawa, T.; Sazuka, T.; Hatakeyama, S.; Goto, K.; Numakura, K.; Yamana, K.; Kandori, S.; Fujita, K.; Ueda, K.; Tanaka, H.; Tomida, R.; Kurahashi, T.; Bando, Y.; Nishiyama, N.; Kimura, T.; Yamashita, S.; Kitamura, H.; Miyake, H. Prognostic outcomes in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving second-line treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitor following first-line immune-oncology combination therapy. Int J Urol. 2024, 31, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 3Das, P.; Booth, A.; Donaldson, R.; Berfeld, N.; Nordstrom, B.; Carroll, R.; Dhokia, P.; Clark, A.; Vaz, L. Patient characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcomes for patients with renal cell carcinoma in England: A retrospective cohort study. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2024, 22, 102081. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).