Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

24 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

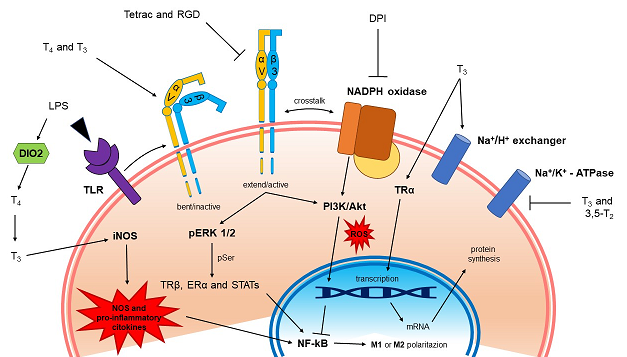

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Evaluation of Cell Viability in BV-2 Microglia by Thyroid Hormones and LPS

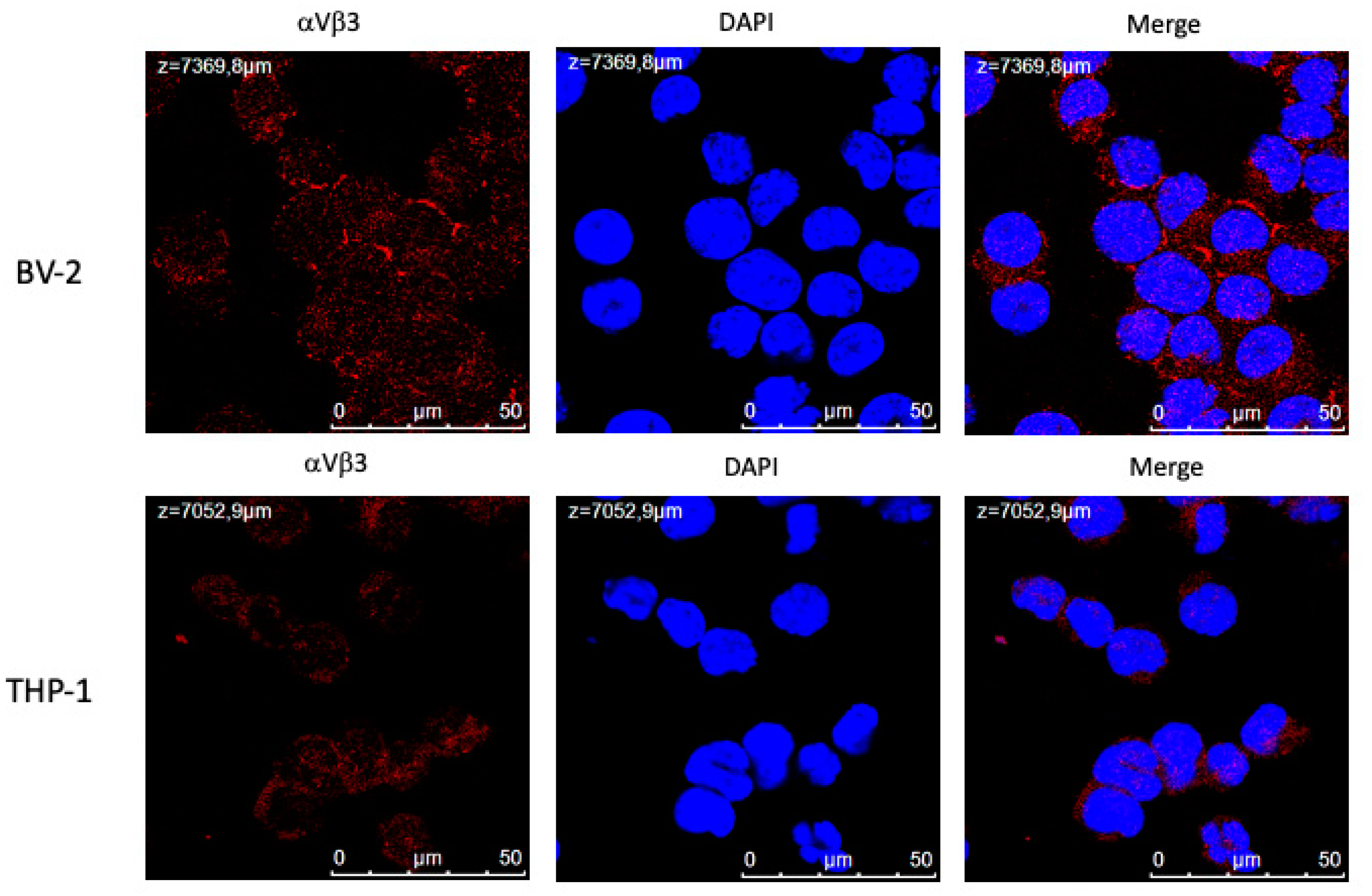

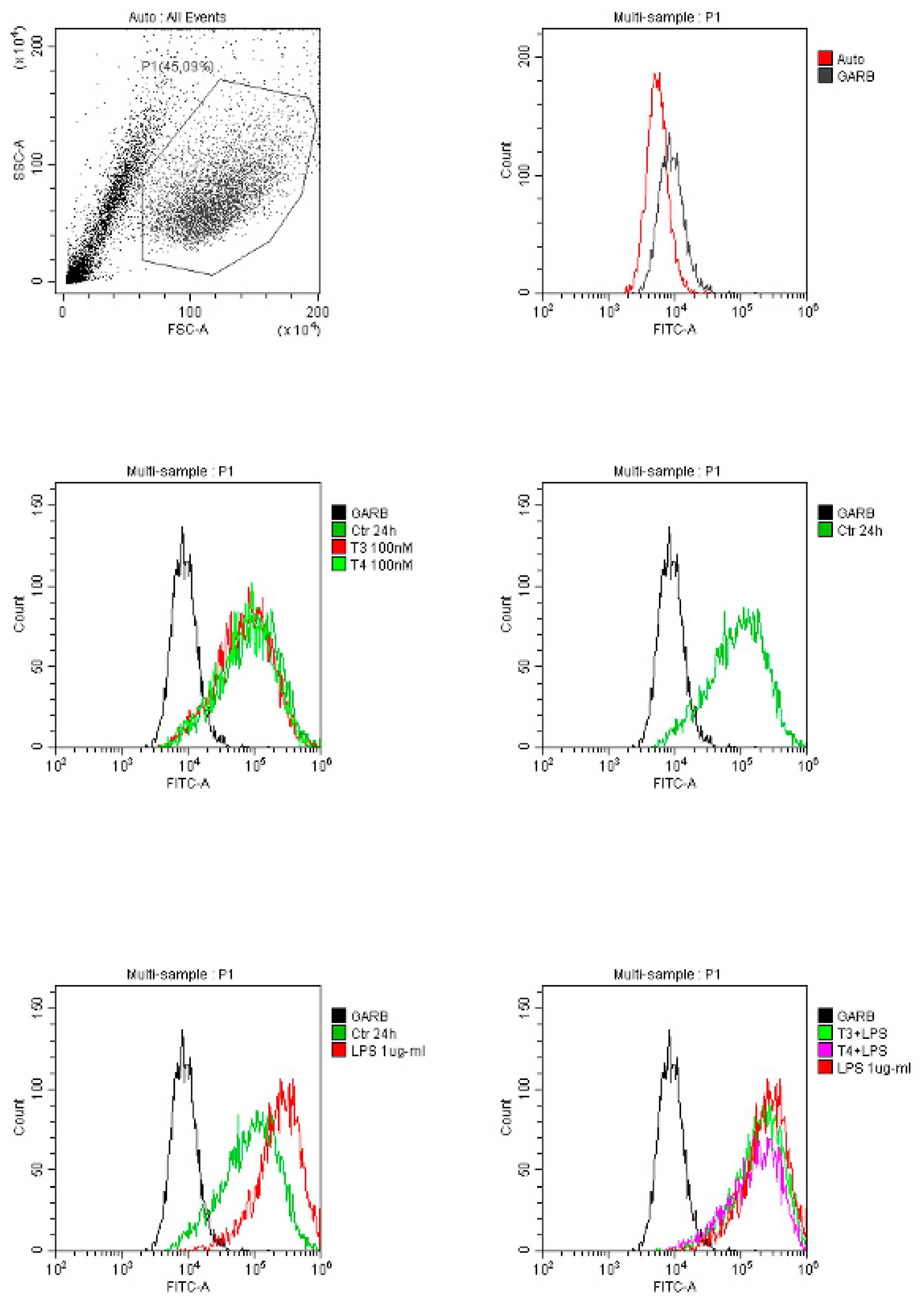

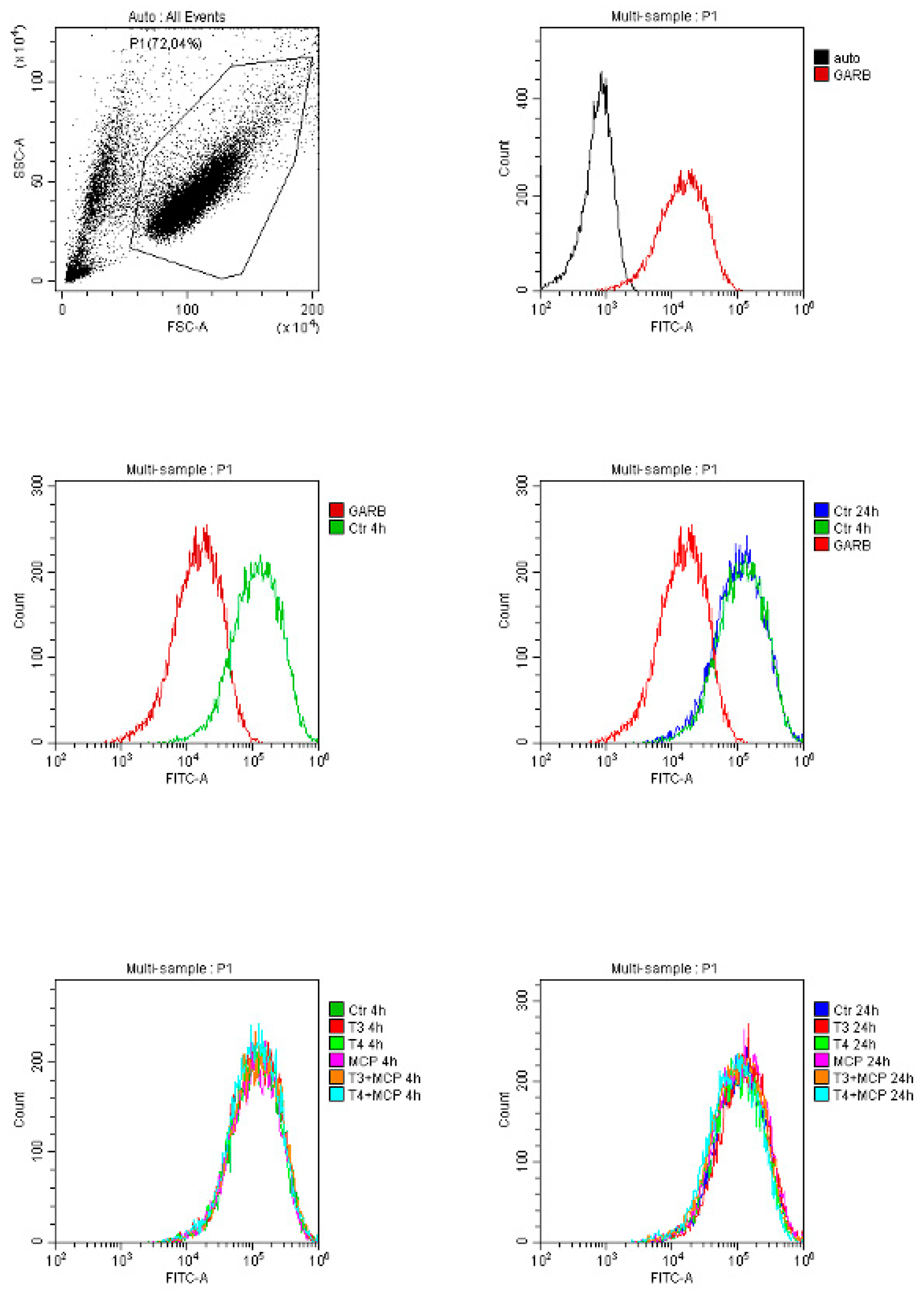

2.2. Expression of αvβ3 Integrin and Its Modulation by Thyroid Hormones

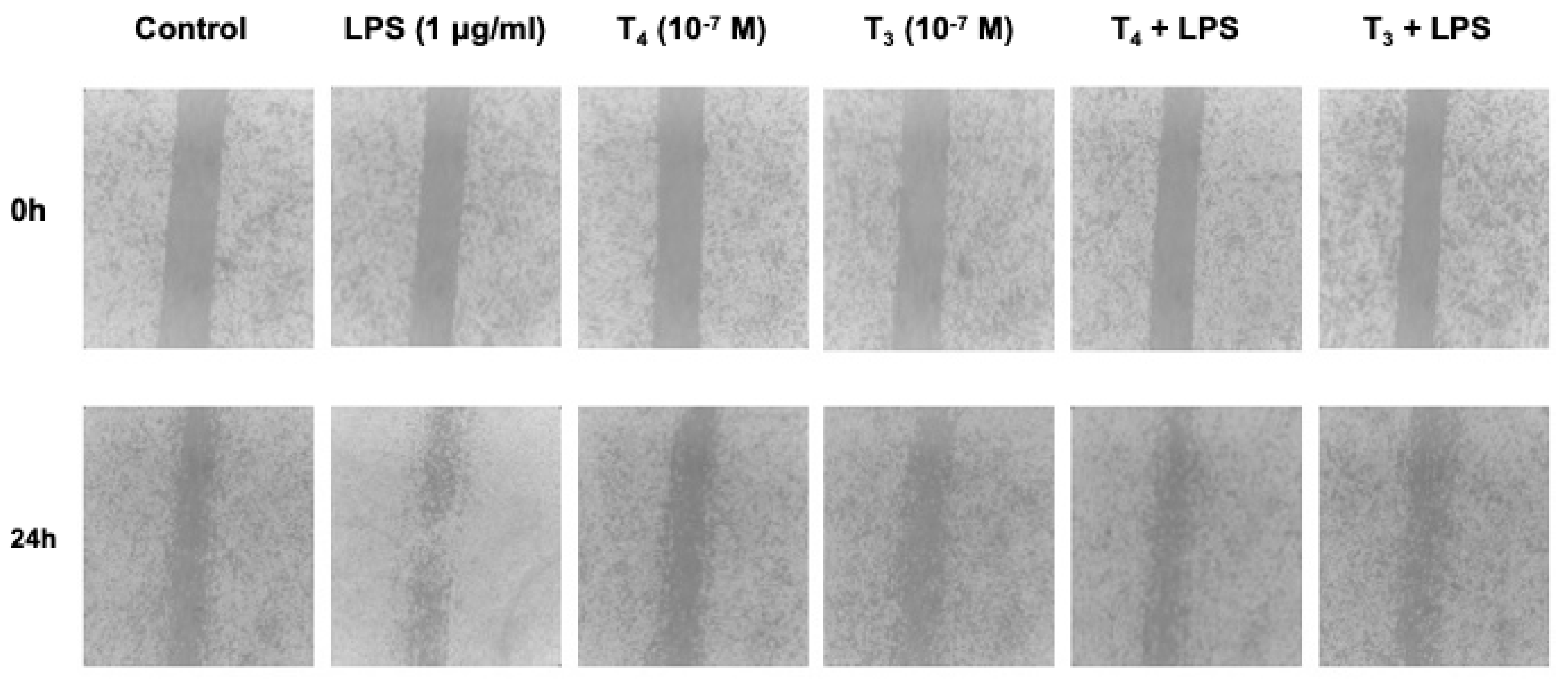

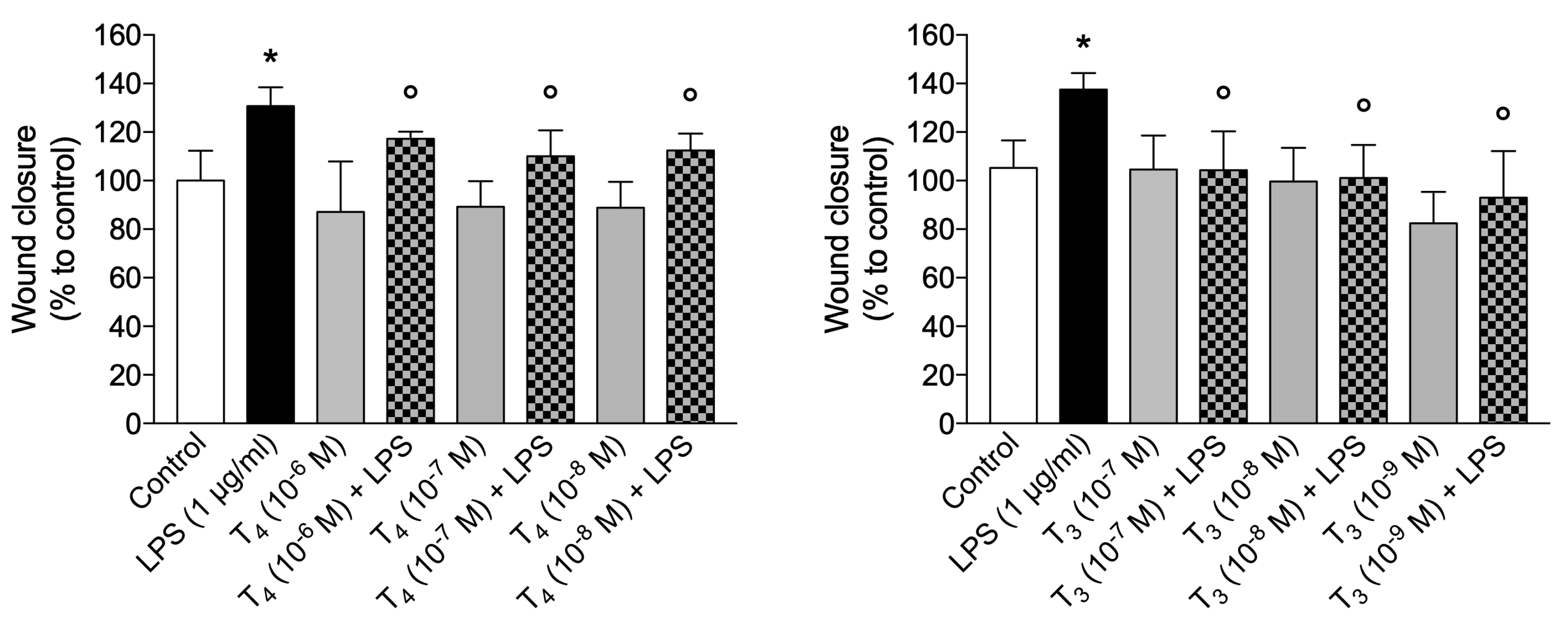

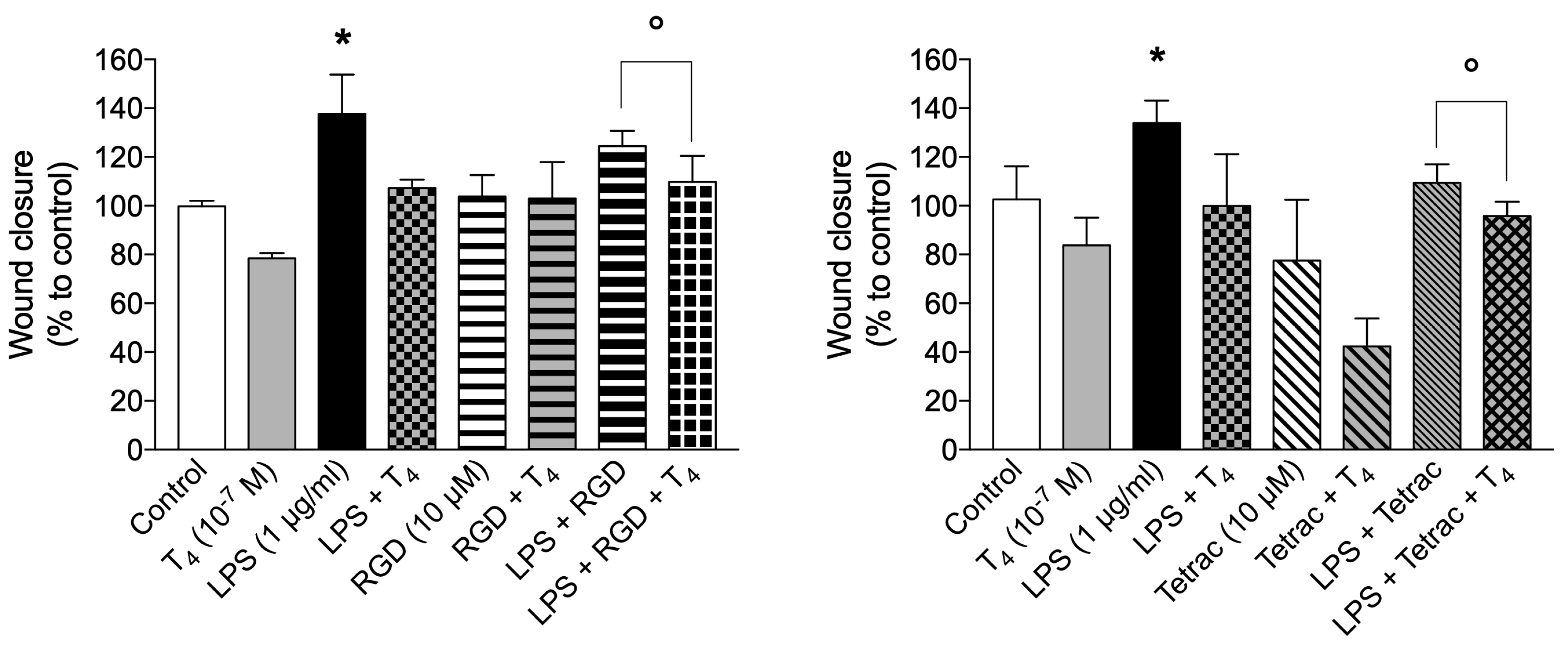

2.3. Thyroid Hormones through Wound Healing Are Able to Regenerate and Repair CNS

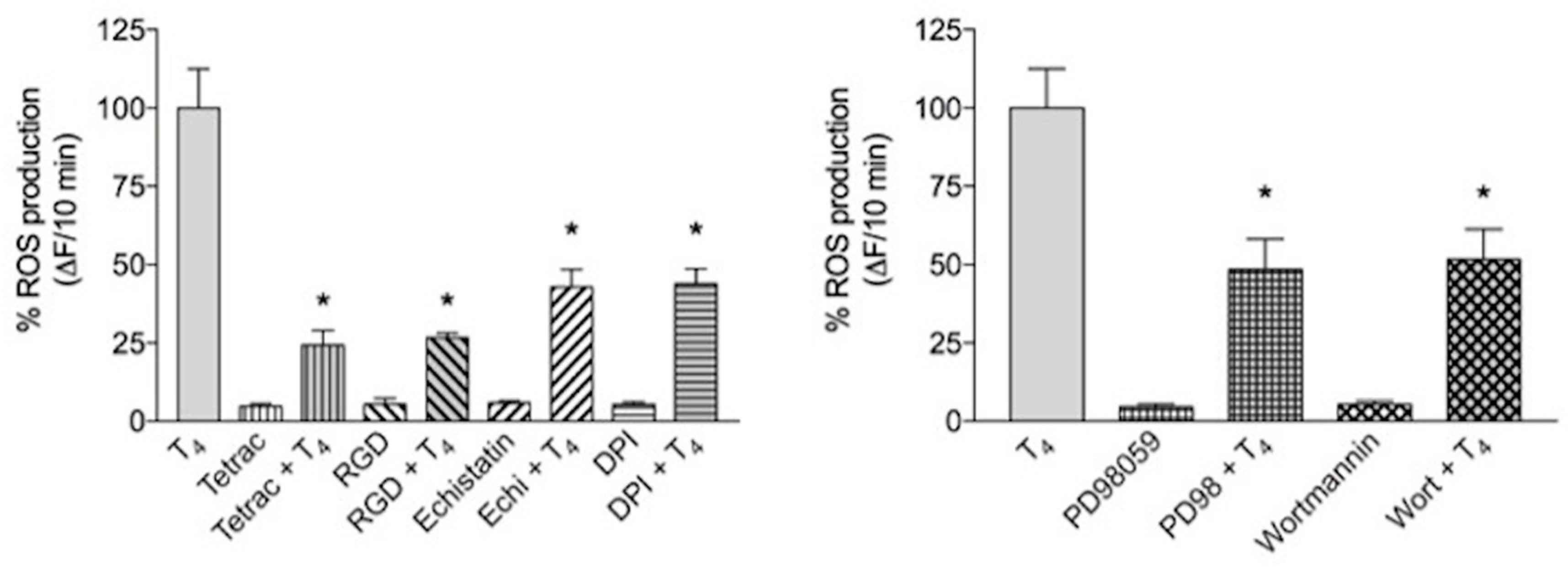

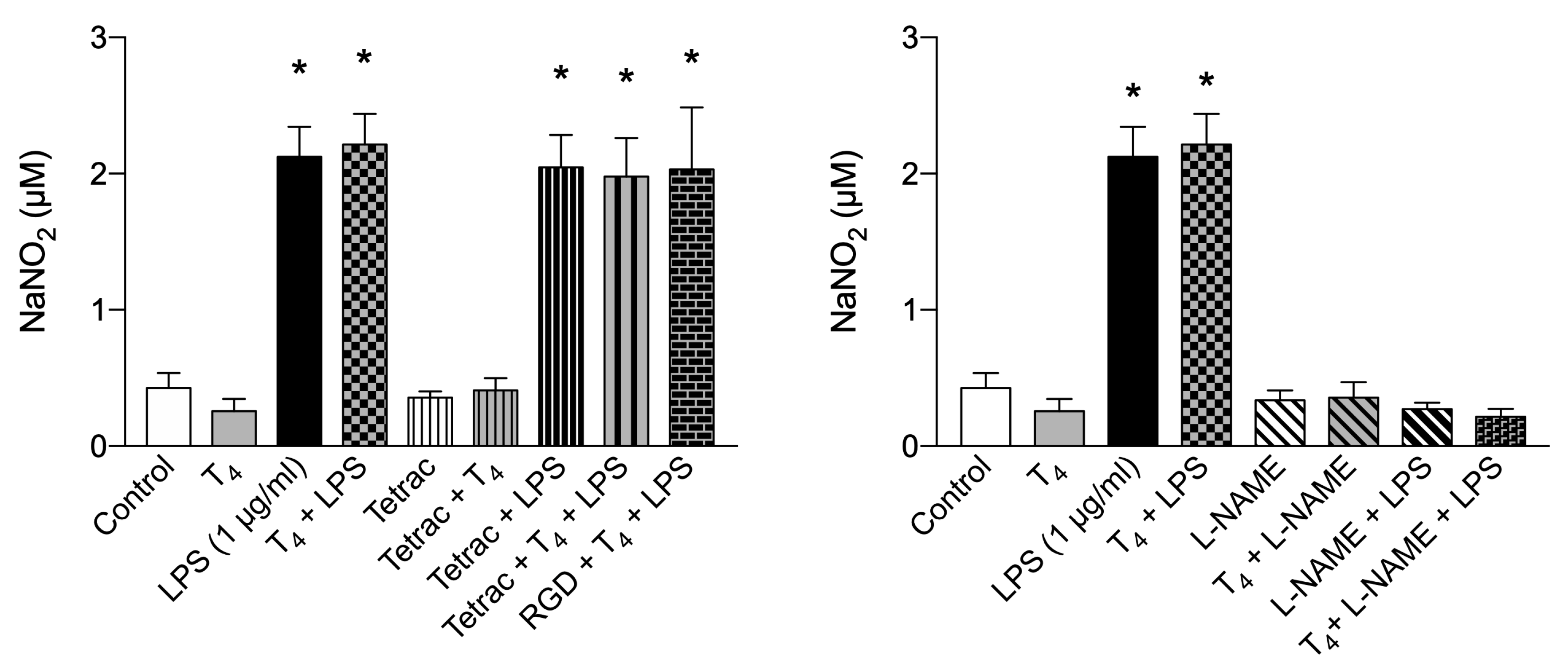

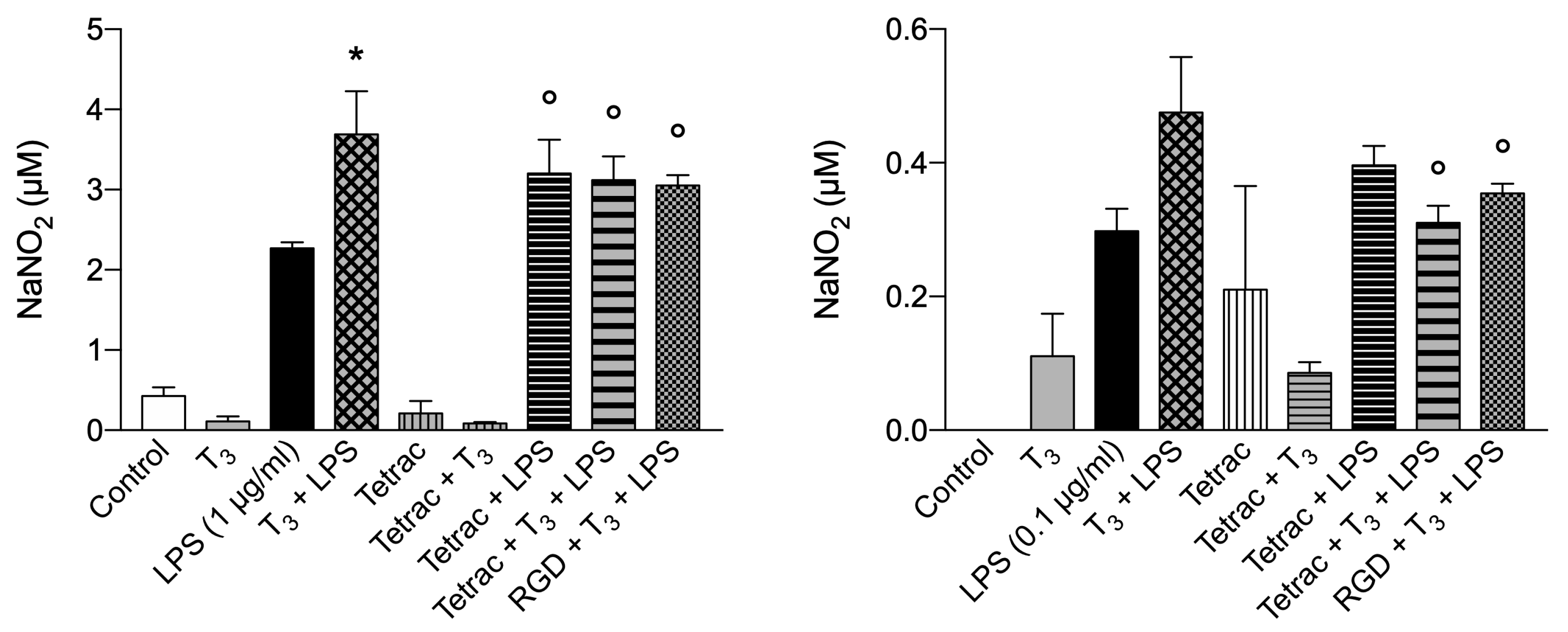

2.4. Production of ROS and NO Induced by Thyroid Hormones: Possible Role of Integrin αvβ3

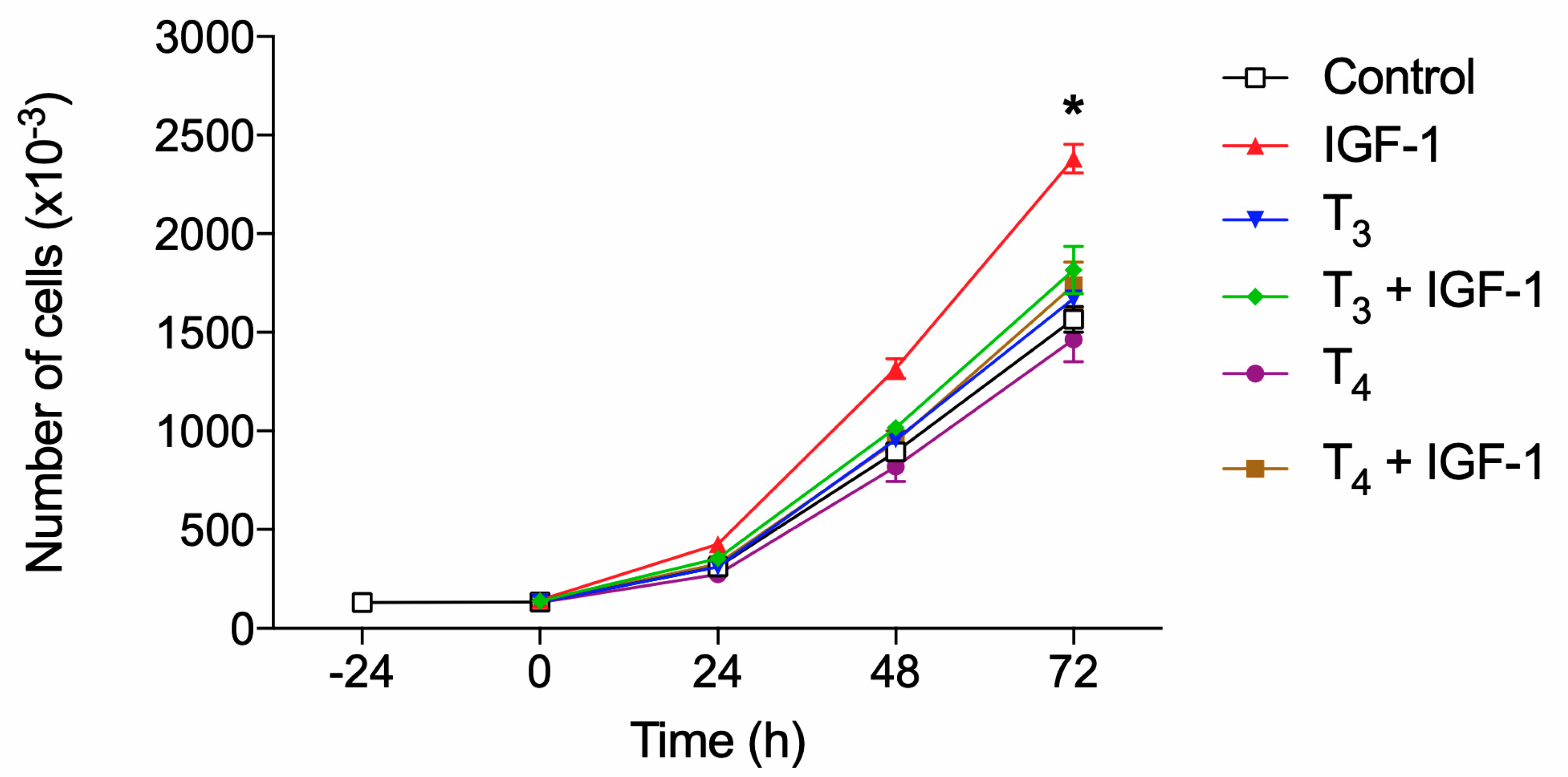

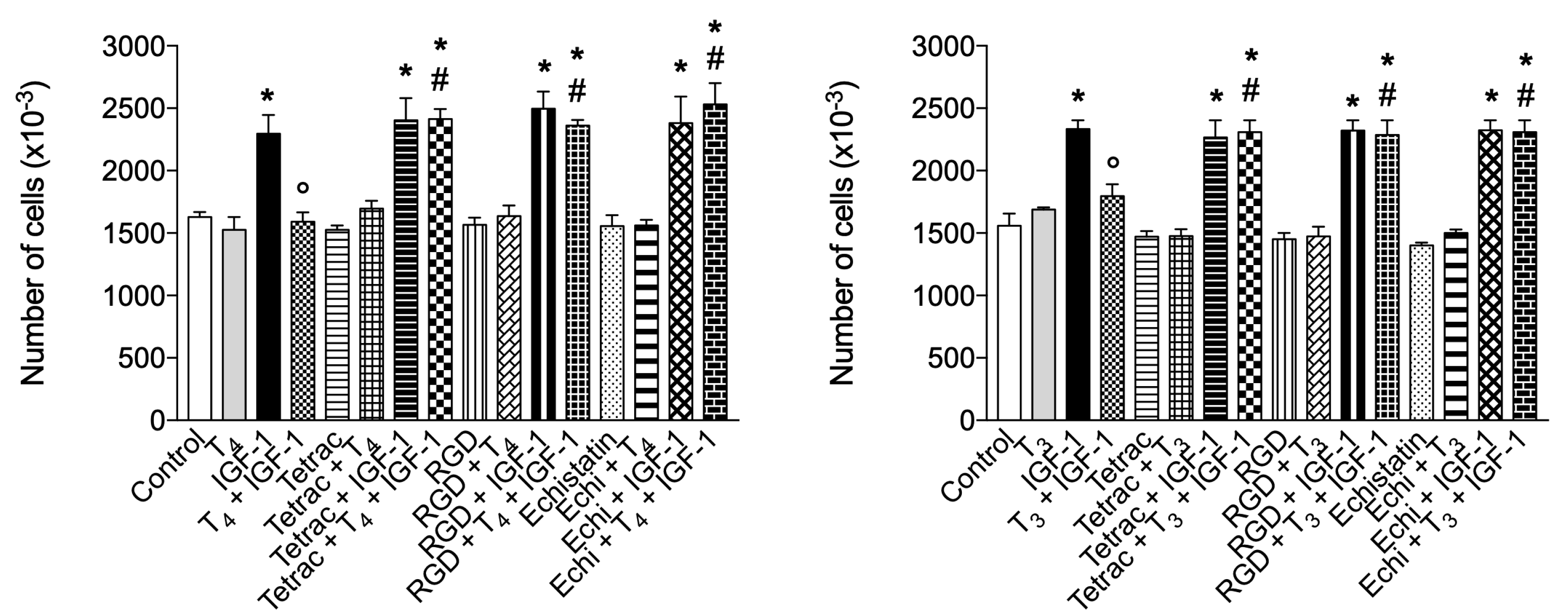

2.5. Effect of Thyroid Hormones and Integrin αvβ3 in Cell Proliferation: Modulation by IGF-1

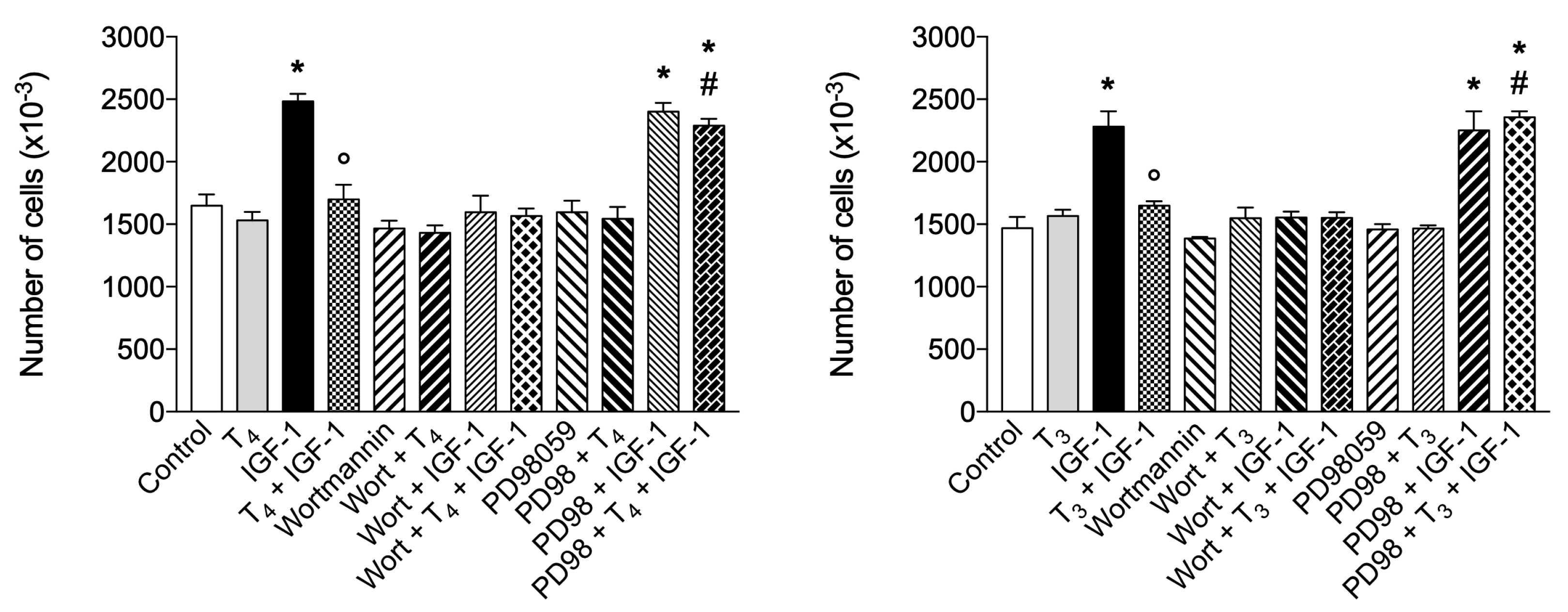

2.6. Signal transduction of BV-2 Proliferation Stimulated by IGF-1 and Thyroid Hormones: Role of MAPK and PI3K Pathways

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells in Culture

4.2. Materials

4.3. Stock Solutions

4.4. MTT Assay

4.5. Immunostaining and Confocal Microscopy

4.6. Flow Cytometry Analysis

4.7. Scratch Wound Assay

4.8. Intracellular ROS Determination

4.9. The Griess Assay

4.10. Proliferation Assay

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α7nAChRs | α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors |

| cAMP | Cyclic AMP |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CX3CL1 | C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1 or Fractalkine |

| CX3CR1 | C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor 1 |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| DAPI | 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DCF | Dichlorofluorescein |

| DIO | Deiodinase |

| DPI | Diphenylene iodonium |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| ERα | Estrogen receptor α |

| HPT | Hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| L-NAME | Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCP-1 | Macrophage chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-Yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| NTIS | Non-thyroidal illness syndrome |

| PAMP | Pathogen-associated molecular pattern |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandine E2 |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase |

| RGD | Arg-Gly-Asp |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| rT3 | Reverse-T3 |

| T2 | 3,5-diiodo-L-thyronine |

| T3 | 3,3′,5-triiodo-L-thyronine |

| T4 | L-thyroxine |

| Tetrac | Tetraiodothyroacetic acid |

| TH | Thyroid hormone |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TR | Thyroid hormone receptor |

| Triac | Triiodothyroacetic acid |

References

- Cheng, S.Y.; Leonard, J.L.; Davis, P.J. Molecular Aspects of Thyroid Hormone Actions. Endocr. Rev. 2010, 31, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Incerpi, S.; Gionfra, F.; De Luca, R.; Candelotti, E.; De Vito, P.; Percario, Z.A.; Leone, S.; Gnocchi, D.; Rossi, M.; Caruso, F.; et al. Extranuclear Effects of Thyroid Hormones and Analogs during Development: An Old Mechanism with Emerging Roles. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 961744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.C.; Privalsky, M.L. Thyroid Hormones, T3 and T4, in the Brain. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2014, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tata, J.R. The Road to Nuclear Receptors of Thyroid Hormone. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 3860–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.R. Neurodevelopmental and Neurophysiological Actions of Thyroid Hormone. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2008, 20, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.J.; Lin, H.Y.; Hercbergs, A.; Keating, K.A.; Mousa, S.A. Possible Contributions of Nongenomic Actions of Thyroid Hormones to the Vasculopathic Complex of COVID-19 Infection. Endocr. Res. 2022, 47, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.C.; Salvatore, D.; Gereben, B.; Berry, M.J.; Larsen, P.R. Biochemistry, Cellular and Molecular Biology, and Physiological Roles of the Iodothyronine Selenodeiodinases. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 38–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzà, L.; Fernández, M.; Giardino, L. Role of the Thyroid System in Myelination and Neural Connectivity. Compr. Physiol. 2015, 5, 1405–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morte, B.; Bernal, J. Thyroid Hormone Action: Astrocyte-Neuron Communication. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2014, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinstroop, E.; van der Spek, A.H.; Boelen, A. Role of Hepatic Deiodinases in Thyroid Hormone Homeostasis and Liver Metabolism, Inflammation, and Fibrosis. Eur. Thyroid J. 2023, 12, e220211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatino, L.; Vassalle, C.; Del Seppia, C.; Iervasi, G. Deiodinases and the Three Types of Thyroid Hormone Deiodination Reactions. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 36, 952–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, J.; Guadaño-Ferraz, A.; Morte, B. Thyroid Hormone Transporters-Functions and Clinical Implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesema, E.C.H.; Ganguly, S.; Abdalla, A.; Fox, J.E.M.; Halestrap, A.P.; Visser, T.J. Identification of Monocarboxylate Transporter 8 as a Specific Thyroid Hormone Transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 40128–40135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dentice, M.; Marsili, A.; Zavacki, A.; Larsen, P.R.; Salvatore, D. The Deiodinases and the Control of Intracellular Thyroid Hormone Signaling during Cellular Differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 3937–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brent, G.A. Mechanisms of Thyroid Hormone Action. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 3035–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergh, J.J.; Lin, H.Y.; Lansing, L.; Mohamed, S.N.; Davis, F.B.; Mousa, S.; Davis, P.J. Integrin αvβ3 Contains a Cell Surface Receptor Site for Thyroid Hormone That Is Linked to Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Induction of Angiogenesis. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 2864–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.J.; Davis, F.B.; Cody, V. Membrane Receptors Mediating Thyroid Hormone Action. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 16, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.J.; Goglia, F.; Leonard, J.L. Nongenomic Actions of Thyroid Hormone. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.J.; Mousa, S.A.; Lin, H.Y. Nongenomic Actions of Thyroid Hormone: The Integrin Component. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 319–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Su, Y.; Hsieh, M.; Lin, S.; Meng, R.; London, D.; Lin, C.; Tang, H.; Hwang, J.; Davis, F.B.; et al. Nuclear Monomeric Integrin αv in Cancer Cells Is a Coactivator Regulated by Thyroid Hormone. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 3209–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Sun, M.; Tang, H.Y.; Lin, C.; Luidens, M.K.; Mousa, S.A.; Incerpi, S.; Drusano, G.L.; Davis, F.B.; Davis, P.J. L-Thyroxine vs. 3,5,3′-Triiodo-L-Thyronine and Cell Proliferation: Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase. Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol. 2009, 296, C980–C991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.J.; Lin, H.Y.; Sudha, T.; Yalcin, M.; Tang, H.Y.; Hercbergs, A.; Leith, J.T.; Luidens, M.K.; Ashur-Fabian, O.; Incerpi, S.; et al. Nanotetrac Targets Integrin αvβ3 on Tumor Cells to Disorder Cell Defense Pathways and Block Angiogenesis. Onco. Targets. Ther. 2014, 7, 1619–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gionfra, F.; De Vito, P.; Pallottini, V.; Lin, H.Y.; Davis, P.J.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Incerpi, S. The Role of Thyroid Hormones in Hepatocyte Proliferation and Liver Cancer. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2019, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, S.A.; Glinsky, G.V.; Lin, H.Y.; Ashur-Fabian, O.; Hercbergs, A.; Keating, K.A.; Davis, P.J. Contributions of Thyroid Hormone to Cancer Metastasis. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calver, J.; Joseph, C.; John, A.; Organ, L.; Fainberg, H.; Porte, J.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Barton, L.; Stroberg, E.; Duval, E.; et al. S31 The Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 Binds RGD Integrins and Upregulates αvβ3 Integrins in Covid-19 Infected Lungs. Thorax 2021, 76, A22–A23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vito, P.; Incerpi, S.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Luly, P.; Davis, F.B.; Davis, P.J. Thyroid Hormones as Modulators of Immune Activities at the Cellular Level. Thyroid 2011, 21, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vito, P.; Balducci, V.; Leone, S.; Percario, Z.A.; Mangino, G.; Davis, P.J.; Davis, F.B.; Affabris, E.; Luly, P.; Pedersen, J.Z.; et al. Nongenomic Effects of Thyroid Hormones on the Immune System Cells: New Targets, Old Players. Steroids 2012, 77, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Switala-Jelen, K.; Dabrowska, K.; Opolski, A.; Lipinska, L.; Nowaczyk, M.; Gorski, A. The Biological Functions of β3 Integrins. Folia Biol. (Praha). 2004, 50, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magsino, C.H.; Hamouda, W.; Ghanim, H.; Browne, R.; Aljada, A.; Dandona, P. Effect of Triiodothyronine on Reactive Oxygen Species Generation by Leukocytes, Indices of Oxidative Damage, and Antioxidant Reserve. Metabolism. 2000, 49, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, M.D.M.; Pellizas, C.G. Thyroid Hormone Action on Innate Immunity. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2019, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelotti, E.; De Luca, R.; Megna, R.; Maiolo, M.; De Vito, P.; Gionfra, F.; Percario, Z.A.; Borgatti, M.; Gambari, R.; Davis, P.J.; et al. Inhibition by Thyroid Hormones of Cell Migration Activated by IGF-1 and MCP-1 in THP-1 Monocytes: Focus on Signal Transduction Events Proximal to Integrin αvβ3. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 651492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiro Arcos, M.L.; Sterle, H.A.; Paulazo, M.A.; Valli, E.; Klecha, A.J.; Isse, B.; Pellizas, C.G.; Farias, R.N.; Cremaschi, G.A. Cooperative Nongenomic and Genomic Actions on Thyroid Hormone Mediated-Modulation of T Cell Proliferation Involve up-Regulation of Thyroid Hormone Receptor and Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226, 3208–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Spek, A.H.; Fliers, E.; Boelen, A. Thyroid Hormone Metabolism in Innate Immune Cells. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 232, R67–R81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzek, C.; Boelen, A.; Westendorf, A.M.; Engel, D.R.; Moeller, L.C.; Führer, D. The Interplay of Thyroid Hormones and the Immune System - Where We Stand and Why We Need to Know about It. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 186, R65–R77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klecha, A.J.; Barreiro Arcos, M.L.; Frick, L.; Genaro, A.M.; Cremaschi, G. Immune-Endocrine Interactions in Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases. Neuroimmunomodulation 2008, 15, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabris, N.; Mocchegiani, E.; Provinciali, M. Pituitary-Thyroid Axis and Immune System: A Reciprocal Neuroendocrine-Immune Interaction. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 1995, 43, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, M.P.; Jensen, E.R.; Montecino-Rodriguez, E.; Leathers, H.; Horseman, N.; Dorshkind, K. Humoral and Cell-Mediated Immunity in Mice with Genetic Deficiencies of Prolactin, Growth Hormone, Insulin-like Growth Factor-I, and Thyroid Hormone. Clin. Immunol. 2000, 96, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, F.; Guasti, L.; Cosentino, M.; De Piazza, D.; Simoni, C.; Piantanida, E.; Cimpanelli, M.; Klersy, C.; Bartalena, L.; Venco, A.; et al. Thyroid Hormone Regulation of Cell Migration and Oxidative Metabolism in Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes: Clinical Evidence in Thyroidectomized Subjects on Thyroxine Replacement Therapy. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R.; Davis, P.J.; Lin, H.Y.; Gionfra, F.; Percario, Z.A.; Affabris, E.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Marchese, C.; Trivedi, P.; Anastasiadou, E.; et al. Thyroid Hormones Interaction With Immune Response, Inflammation and Non-Thyroidal Illness Syndrome. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 614030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciacchitano, S.; De Vitis, C.; D’Ascanio, M.; Giovagnoli, S.; De Dominicis, C.; Laghi, A.; Anibaldi, P.; Petrucca, A.; Salerno, G.; Santino, I.; et al. Gene Signature and Immune Cell Profiling by High-Dimensional, Single-Cell Analysis in COVID-19 Patients, Presenting Low T3 Syndrome and Coexistent Hematological Malignancies. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sror-Turkel, O.; El-Khatib, N.; Sharabi-Nov, A.; Avraham, Y.; Merchavy, S. Low TSH and Low T3 Hormone Levels as a Prognostic for Mortality in COVID-19 Intensive Care Patients. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2024, 15, 1322487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarlus, H.; Heneka, M.T. Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, J.D.; Olschowka, J.A.; O’Banion, M.K. Neuroinflammation and M2 Microglia: The Good, the Bad, and the Inflamed. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Wang, H.; Yin, Y. Microglia Polarization From M1 to M2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 815347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.R.S.; Gervais, A.; Colin, C.; Izembart, M.; Neto, V.M.; Mallat, M. Regulation of Microglial Development: A Novel Role for Thyroid Hormone. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 2028–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, M. Possible Role of Glial Cells in the Relationship between Thyroid Dysfunction and Mental Disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, M. Thyroid Hormone in the CNS: Contribution of Neuron-Glia Interaction. Vitam Horm. 2018, 106, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, C.; De Palma, C.; Clementi, E.; Cervia, D. Hormones and Immunity in Cancer: Are Thyroid Hormones Endocrine Players in the Microglia/Glioma Cross-Talk? Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, C.; Buldorini, M.; Assi, E.; Cazzato, D.; De Palma, C.; Clementi, E.; Cervia, D. The Thyroid Hormone Triiodothyronine Controls Macrophage Maturation and Functions: Protective Role during Inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sjölinder, M.; Wang, X.; Altenbacher, G.; Hagner, M.; Berglund, P.; Gao, Y.; Lu, T.; Jonsson, A.B.; Sjölinder, H. Thyroid Hormone Enhances Nitric Oxide-Mediated Bacterial Clearance and Promotes Survival after Meningococcal Infection. PLoS One 2012, 7, e41445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.R. The Immune System as a Regulator of Thyroid Hormone Activity. Exp. Biol. Med. 2006, 231, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannocco, G.; Kizys, M.M.L.; Maciel, R.M.; de Souza, J.S. Thyroid Hormone, Gene Expression, and Central Nervous System: Where We Are. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 114, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariyani, W.; Miyazaki, W.; Amano, I.; Koibuchi, N. Involvement of Integrin αvβ3 in Thyroid Hormone-Induced Dendritogenesis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 938596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, R.; Campbell, I.L. The Extracellular Matrix and Cytokines Regulate Microglial Integrin Expression and Activation. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 3850–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloss, C.U.A.; Bohatschek, M.; Kreutzberg, G.W.; Raivich, G. Effect of Lipopolysaccharide on the Morphology and Integrin Immunoreactivity of Ramified Microglia in the Mouse Brain and in Cell Culture. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 168, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellacasagrande, J.; Ghigo, E.; Hammami, S.M.E.; Toman, R.; Raoult, D.; Capo, C.; Mege, J.L. αvβ3 Integrin and Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Are Involved in Coxiella Burnetii-Stimulated Production of Tumor Necrosis Factor by Human Monocytes. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 5673–5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiSabato, D.J.; Quan, N.; Godbout, J.P. Neuroinflammation: The Devil Is in the Details. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graeber, M.B.; Streit, W.J. Microglia: Biology and Pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lively, S.; Schlichter, L.C. The Microglial Activation State Regulates Migration and Roles of Matrix-Dissolving Enzymes for Invasion. J. Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.C. The Endotoxin Hypothesis of Neurodegeneration. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava Catorce, M.; Gevorkian, G. LPS-Induced Murine Neuroinflammation Model: Main Features and Suitability for Pre-Clinical Assessment of Nutraceuticals. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogland, I.C.M.; Houbolt, C.; van Westerloo, D.J.; van Gool, W.A.; van de Beek, D. Systemic Inflammation and Microglial Activation: Systematic Review of Animal Experiments. J. Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orihuela, R.; McPherson, C.A.; Harry, G.J. Microglial M1/M2 Polarization and Metabolic States. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, C.D.; Melchior, B.; Masek, K.; Puntambekar, S.S.; Danielson, P.E.; Lo, D.D.; Gregor Sutcliffe, J.; Carson, M.J. Differential Gene Expression in LPS/IFNγ Activated Microglia and Macrophages: In Vitro versus in Vivo. J. Neurochem. 2009, 109, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davalos, D.; Grutzendler, J.; Yang, G.; Kim, J.V.; Zuo, Y.; Jung, S.; Littman, D.R.; Dustin, M.L.; Gan, W.B. ATP Mediates Rapid Microglial Response to Local Brain Injury in Vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, P.J.; Glinsky, G.V.; Lin, H.Y.; Mousa, S.A. Actions of Thyroid Hormone Analogues on Chemokines. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.J.; Glinsky, G.V.; Lin, H.Y.; Incerpi, S.; Davis, F.B.; Mousa, S.A.; Tang, H.Y.; Hercbergs, A.; Luidens, M.K. Molecular Mechanisms of Actions of Formulations of the Thyroid Hormone Analogue, Tetrac, on the Inflammatory Response. Endocr. Res. 2013, 38, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Takada, Y.K.; Takada, Y. The Chemokine Fractalkine Can Activate Integrins without CX3CR1 through Direct Binding to a Ligand-Binding Site Distinct from the Classical RGD-Binding Site. PLoS One 2014, 9, e96372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Takada, Y.K.; Takada, Y. Integrins αvβ3 and α4β1 Act as Coreceptors for Fractalkine, and the Integrin-Binding Defective Mutant of Fractalkine Is an Antagonist of CX3CR1. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 5809–5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, A.G.; Engler, D.; Sakoloff, C.; Staeheli, V. The Effects of Tetraiodothyroacetic and Triiodothyroacetic Acids on Thyroid Function in Euthyroid and Hyperthyroid Subjects. Acta Endocrinol. (Copenh). 1979, 92, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M.; De Lange, P.; Lombardi, A.; Silvestri, E.; Lanni, A.; Goglia, F. Metabolic Effects of Thyroid Hormone Derivatives. Thyroid 2008, 18, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Song, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y. Reactive Oxygen Species Regulate T Cell Immune Response in the Tumor Microenvironment. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1580967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Martín, A.; Griendling, K.K. Redox Control of Vascular Smooth Muscle Migration. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) as Pleiotropic Physiological Signalling Agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarugi, P.; Buricchi, F. Protein Tyrosine Phosphorylation and Reversible Oxidation: Two Cross-Talking Posttranslation Modifications. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2007, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarugi, P.; Fiaschi, T. Redox Signalling in Anchorage-Dependent Cell Growth. Cell. Signal. 2007, 19, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saudek, V.; Andrew Atkinson, R.; Pelton, J.T. Three-Dimensional Structure of Echistatin, the Smallest Active RGD Protein. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 7369–7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goitre, L.; Pergolizzi, B.; Ferro, E.; Trabalzini, L.; Retta, S.F. Molecular Crosstalk between Integrins and Cadherins: Do Reactive Oxygen Species Set the Talk? J. Signal Transduct. 2012, 2012, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.N.; Al-Omran, A.; Parvathy, S.S. Role of Nitric Oxide in Inflammatory Diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2007, 15, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, M.M.; Gluvic, Z.M.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.M.; Panic, A.; Trebaljevac, J.; Bajic, V.B.; Zarkovic, M.; Isenovic, E.R. Nitric Oxide as a Marker for Levo-Thyroxine Therapy in Subclinical Hypothyroid Patients. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2016, 14, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persichini, T.; Cantoni, O.; Suzuki, H.; Colasanti, M. Cross-Talk between Constitutive and Inducible NO Synthase: An Update. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluvic, Z.M.; Obradovic, M.M.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.M.; Zafirovic, S.S.; Radak, D.J.; Essack, M.M.; Bajic, V.B.; Takashi, G.; Isenovic, E.R. Regulation of Nitric Oxide Production in Hypothyroidism. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 124, 109881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada, A.; Sainz, J.; Wangensteen, R.; Rodriguez-Gomez, I.; Vargas, F.; Osuna, A. Nitric Oxide Synthase Activity in Hyperthyroid and Hypothyroid Rats. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2002, 147, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhari, M.M.; Sattar, H.; Malik, A.; Khurshid, R.; Aamir, F.; Malik, A. Interplay of Thyroid Hormones, Nitric Oxide and Nitric Oxide Synthase in Potentiating the Breast Cancer Metastasis. Pakistan J. Med. Heal. Sci. 2022, 16, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Viscovo, A.; Secondo, A.; Esposito, A.; Goglia, F.; Moreno, M.; Canzoniero, L.M.T. Intracellular and Plasma Membrane-Initiated Pathways Involved in the [Ca2+]i Elevations Induced by Iodothyronines (T3 and T2) in Pituitary GH3 Cells. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 302, E1419–E1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toral, M.; Jimenez, R.; Montoro-Molina, S.; Romero, M.; Wangensteen, R.; Duarte, J.; Vargas, F. Thyroid Hormones Stimulate L-Arginine Transport in Human Endothelial Cells. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 239, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, E.M.; Kwakkel, J.; Eggels, L.; Kalsbeek, A.; Barrett, P.; Fliers, E.; Boelen, A. NFκB Signaling Is Essential for the Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Increase of Type 2 Deiodinase in Tanycytes. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 2000–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, T.; Hajihosseini, M.K. Hypothalamic Tanycytes-Masters and Servants of Metabolic, Neuroendocrine, and Neurogenic Functions. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevot, V.; Dehouck, B.; Sharif, A.; Ciofi, P.; Giacobini, P.; Clasadonte, J. The Versatile Tanycyte: A Hypothalamic Integrator of Reproduction and Energy Metabolism. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 333–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.M.; Kim, S.W.; Salvatore, D.; Bartha, T.; Legradi, G.; Larsen, P.R.; Lechan, R.M. Regional Distribution of Type 2 Thyroxine Deiodinase Messenger Ribonucleic Acid in Rat Hypothalamus and Pituitary and Its Regulation by Thyroid Hormone. Endocrinology 1997, 138, 3359–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakuno, F.; Takahashi, S.I. 40 Years of IGF1: IGF1 Receptor Signaling Pathways. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 61, T69–T86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laron, Z. Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF-1): A Growth Hormone. J. Clin. Pathol. - Mol. Pathol. 2001, 54, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillon, N.J.; Bilan, P.J.; Fink, L.N.; Klip, A. Cross-Talk between Skeletal Muscle and Immune Cells: Muscle-Derived Mediators and Metabolic Implications. Am. J. Physiol. - Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 304, E453–E465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.E.; Dantzer, R.; Kelley, K.W.; McCusker, R.H. Central Administration of Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Decreases Depressive-like Behavior and Brain Cytokine Expression in Mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2011, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhanov, S.; Higashi, Y.; Shai, S.Y.; Vaughn, C.; Mohler, J.; Li, Y.; Song, Y.H.; Titterington, J.; Delafontaine, P. IGF-1 Reduces Inflammatory Responses, Suppresses Oxidative Stress, and Decreases Atherosclerosis Progression in ApoE-Deficient Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 2684–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.M.; Torres-Alemán, I. The Many Faces of Insulin-like Peptide Signalling in the Brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, D.L.; Bondy, C.A.; Brenner, M.; Hudson, L.D.; Zhou, J.; Webster, H.D. Astrocytes Express Insulin-like Growth Factor-I (IGF-I) and Its Binding Protein, IGFBP-2, during Demyelination Induced by Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1994, 5, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemva, J.; Schubert, M. The Role of Neuronal Insulin/Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Signaling for the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Possible Therapeutic Implications. CNS Neurol. Disord. - Drug Targets 2014, 13, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incerpi, S.; Hsieh, M.T.; Lin, H.Y.; Cheng, G.Y.; De Vito, P.; Fiore, A.M.; Ahmed, R.G.; Salvia, R.; Candelotti, E.; Leone, S.; et al. Thyroid Hormone Inhibition in L6 Myoblasts of IGF-I-Mediated Glucose Uptake and Proliferation: New Roles for Integrin αvβ3. Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol. 2014, 307, C150–C161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saegusa, J.; Yamaji, S.; Ieguchi, K.; Wu, C.Y.; Lam, K.S.; Liu, F.T.; Takada, Y.K.; Takada, Y. The Direct Binding of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) to Integrin αvβ3 Is Involved in IGF-1 Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 24106–24114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, M.; Takada, Y.K.; Takada, Y. Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) Signaling Requires αvβ3-IGF1-IGF Type 1 Receptor (IGF1R) Ternary Complex Formation in Anchorage Independence, and the Complex Formation Does Not Require IGF1R and Src Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 3059–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemmons, D.R. Role of IGF-I in Skeletal Muscle Mass Maintenance. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 20, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baserga, R.; Hongo, A.; Rubini, M.; Prisco, M.; Valentinis, B. The IGF-I Receptor in Cell Growth, Transformation and Apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Rev. Cancer 1997, 1332, F105–F126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedemann, J.; Macaulay, V.M. IGF1R Signalling and Its Inhibition. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2006, 13, S33–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borst, K.; Dumas, A.A.; Prinz, M. Microglia: Immune and Non-Immune Functions. Immunity 2021, 54, 2194–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.U.; De Vellis, J. Microglia in Health and Disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005, 81, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasa, M.; Contreras-Jurado, C. Thyroid Hormones Act as Modulators of Inflammation through Their Nuclear Receptors. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 937099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Tomonaga, D.; Kalashnikova, A.; Furuya, F.; Akimoto, N.; Ifuku, M.; Okuno, Y.; Beppu, K.; Fujita, K.; Katafuchi, T.; et al. Effects of 3,3′,5-Triiodothyronine on Microglial Functions. Glia 2015, 63, 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, A.S.; Antonova, G.N.; Munn, D.H.; Mivechi, N.; Lucas, R.; Catravas, J.D.; Verin, A.D. αvβ3 Integrin Regulates Macrophage Inflammatory Responses via PI3 Kinase/Akt-Dependent NF-ΚB Activation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, T.; Leoni, V.; Chesnokova, L.S.; Hutt-Fletcher, L.M.; Campadelli-Fiume, G. αvβ3-Integrin Is a Major Sensor and Activator of Innate Immunity To Herpes Simplex Virus-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 19792–19797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurihara, Y.; Nakahara, T.; Furue, M. αvβ3-Integrin Expression through ERK Activation Mediates Cell Attachment and Is Necessary for Production of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha in Monocytic THP-1 Cells Stimulated by Phorbol Myristate Acetate. Cell. Immunol. 2011, 270, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monick, M.M.; Powers, L.; Butler, N.; Yarovinsky, T.; Hunninghake, G.W. Interaction of Matrix with Integrin Receptors Is Required for Optimal LPS-Induced MAP Kinase Activation. Am. J. Physiol. - Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2002, 283, L390–L402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonov, A.S.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Munn, D.H.; Gerrity, R.G. Regulation of Macrophage Foam Cell Formation by αvβ3 Integrin: Potential Role in Human Atherosclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 165, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, R. Microglial Expression of αvβ3 and αvβ5 Integrins Is Regulated by Cytokines and the Extracellular Matrix: β5 Integrin Null Microglia Show No Defects in Adheison or MMP-9 Expression on Vitronectin. Glia 2009, 57, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Donangelo, I.; Abe, K.; Scremin, O.; Ke, S.; Li, F.; Milanesi, A.; Liu, Y.Y.; Brent, G.A. Thyroid Hormone Treatment Activates Protective Pathways in Both in Vivo and in Vitro Models of Neuronal Injury. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 452, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Brent, G.A. Thyroid Hormone and the Brain: Mechanisms of Action in Development and Role in Protection and Promotion of Recovery after Brain Injury. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 186, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, L.; Godbole, M.M.; Sinha, R.A.; Pradhan, S. Reverse Triiodothyronine (rT3) Attenuates Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 506, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julier, Z.; Park, A.J.; Briquez, P.S.; Martino, M.M. Promoting Tissue Regeneration by Modulating the Immune System. Acta Biomater. 2017, 53, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safer, J.D.; Crawford, T.M.; Holick, M.F. A Role for Thyroid Hormone in Wound Healing through Keratin Gene Expression. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 2357–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safer, J.D. Thyroid Hormone and Wound Healing. J. Thyroid Res. 2013, 2013, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.V.; Zajtchuk, J.T.; Henderson, R.L. Hypothyroidism and Wound Healing: Occurrence After Head and Neck Radiation and Surgery. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1982, 108, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoǧan, M.; Ilhan, Y.S.; Akkuş, M.A.; Caboǧlu, S.A.; Özercan, I.; Ïlhan, N.; Yaman, M. Effects of L-Thyroxine and Zinc Therapy on Wound Healing in Hypothyroid Rats. Acta Chir. Belg. 1999, 99, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herndon, D.N.; Wilmore, D.W.; Mason, A.D.; Curreri, P.W. Increased Rates of Wound Healing in Burned Guinea Pigs Treated with L-Thyroxine. Surg. Forum 1979, 30, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kassem, R.; Liberty, Z.; Babaev, M.; Trau, H.; Cohen, O. Harnessing the Skin-Thyroid Connection for Wound Healing: A Prospective Controlled Trial in Guinea Pigs. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2012, 37, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehregan, A.H.; Zamick, P. The Effect of Triiodothyronine in Healing of Deep Dermal Burns and Marginal Scars of Skin Grafts. A Histologic Study. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1974, 1, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natori, J.; Shimizu, K.; Nagahama, M.; Tanaka, S. The Influence of Hypothyroidism on Wound Healing. An Experimental Study. Nippon Ika Daigaku zasshi 1999, 66, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safer, J.D.; Crawford, T.M.; Holick, M.F. Topical Thyroid Hormone Accelerates Wound Healing in Mice. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 4425–4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talmi, Y.P.; Finkelstein, Y.; Zohar, Y. Pharyngeal Fistulas in Postoperative Hypothyroid Patients. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1989, 98, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamick, P.; Mehregan, A.H. Effect of 1-Tri-Iodothyronine on Marginal Scars of Skin Grafted Burns in Rats. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1973, 51, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.R. Hypothyroidism in Head and Neck Cancer Patients Experimental and Clinical Observations. Laryngoscope 1994, 104, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladenson, P.W.; Levin, A.A.; Ridgway, E.C.; Daniels, G.H. Complications of Surgery in Hypothyroid Patients. Am. J. Med. 1984, 77, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirk, F.W.; Elattar, T.M.A.; Roth, G.D. Effect of Analogues of Steroid and Thyroxine Hormones on Wound Healing in Hamsters. J. Periodontal Res. 1974, 9, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnardt, S.; Massillon, L.; Follett, P.; Jensen, F.E.; Ratan, R.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Volpe, J.J.; Vartanian, T. Activation of Innate Immunity in the CNS Triggers Neurodegeneration through a Toll-like Receptor 4-Dependent Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 8514–8519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, J.; Ingbar, S.H. 3,5,3′-Triiodothyronine Increases Cellular Adenosine 3′,5′-Monophosphate Concentration and Sugar Uptake in Rat Thymocytes by Stimulating Adenylate Cyclase Activity: Studies with the Adenylate Cyclase Inhibitor MDL 12330A. Endocrinology 1989, 124, 2166–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incerpi, S.; Ashur-Fabian, O.; Davis, P.J.; Pedersen, J.Z. Editorial: Crosstalk between Thyroid Hormones, Analogs and Ligands of Integrin αvβ3 in Health and Disease. Who Is Talking Now? Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2023, 13, 1119952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapin, S.; Leoni, S.; Spagnuolo, S.; Gnocchi, D.; De Vito, P.; Luly, P.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Incerpi, S. Short-Term Effects of Thyroid Hormones during Development: Focus on Signal Transduction. Steroids 2010, 75, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapin, S.; Leoni, S.; Spagnuolo, S.; Fiore, A.M.; Incerpi, S. Short-Term Effects of Thyroid Hormones on Na+-K+-ATPase Activity of Chick Embryo Hepatocytes during Development: Focus on Signal Transduction. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2009, 296, C4–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovikova, L.V.; Ivanova, S.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Botchkina, G.I.; Watkins, L.R.; Wang, H.; Abumrad, N.; Eaton, J.W.; Tracey, K.J. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Attenuates the Systemic Inflammatory Response to Endotoxin. Nature 2000, 405, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chiu, K.T.; Sun, Y.T.; Chen, W.C. Role of the Cyclic AMP-Protein Kinase A Pathway in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression in RAW 264.7 Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 31559–31564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Spek, A.H.; Surovtseva, O.V.; Jim, K.K.; van Oudenaren, A.; Brouwer, M.C.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.J.E.; Leenen, P.J.M.; van de Beek, D.; Hernandez, A.; Fliers, E.; et al. Regulation of Intracellular Triiodothyronine Is Essential for Optimal Macrophage Function. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 2241–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, M.; Werner, S. Oxidative Stress in Normal and Impaired Wound Repair. Pharmacol. Res. 2008, 58, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiro Arcos, M.L.; Sterle, H.A.; Vercelli, C.; Valli, E.; Cayrol, M.F.; Klecha, A.J.; Paulazo, M.A.; Diaz Flaqué, M.C.; Franchi, A.M.; Cremaschi, G.A. Induction of Apoptosis in T Lymphoma Cells by Long-Term Treatment with Thyroxine Involves PKCζ Nitration by Nitric Oxide Synthase. Apoptosis 2013, 18, 1376–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelotti, E.; De Vito, P.; Ahmed, R.G.; Luly, P.; Davis, P.J.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Lin, H.Y.; Incerpi, S. Thyroid Hormones Crosstalk with Growth Factors: Old Facts and New Hypotheses. Immunol. Endocr. Metab. Agents Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Shih, A.; Davis, F.B.; Davis, P.J. Thyroid Hormone Promotes the Phosphorylation of STAT3 and Potentiates the Action of Epidermal Growth Factor in Cultured Cells. Biochem. J. 1999, 338, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.Y.; Davis, F.B.; Gordinier, J.K.; Martino, L.J.; Davis, P.J. Thyroid Hormone Induces Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase in Cultured Cells. Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol. 1999, 276, C1014–C1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Arnao, J.; Miell, J.P.; Ross, R.J.M. Influence of Thyroid Hormones on the GH-IGF-I Axis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 1993, 4, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, A.; Zhang, S.; Cao, H.J.; Tang, H.Y.; Davis, F.B.; Davis, P.J.; Lin, H.Y. Disparate Effects of Thyroid Hormone on Actions of Epidermal Growth Factor and Transforming Growth Factor-α Are Mediated by 3′,5′-Cyclic Adenosine 5′-Monophosphate-Dependent Protein Kinase II. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Sun, M.; Lin, C.; Tang, H.Y.; London, D.; Shih, A.; Davis, F.B.; Davis, P.J. Androgen-Induced Human Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation Is Mediated by Discrete Mechanisms in Estrogen Receptor-α-Positive and -Negative Breast Cancer Cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009, 113, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Tang, H.Y.; Davis, F.B.; Davis, P.J. Resveratrol and Apoptosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.Y.; Cody, V.; Davis, F.B.; Hercbergs, A.A.; Luidens, M.K.; Mousa, S.A.; Davis, P.J. Identification and Functions of the Plasma Membrane Receptor for Thyroid Hormone Analogues. Discov. Med. 2011, 11, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freindorf, M.; Furlani, T.R.; Kong, J.; Cody, V.; Davis, F.B.; Davis, P.J. Combined QM/MM Study of Thyroid and Steroid Hormone Analogue Interactions with αvβ3 Integrin. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 959057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, S.; Raja, K.; Schweizer, U.; Mugesh, G. Chemistry and Biology in the Biosynthesis and Action of Thyroid Hormones. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7606–7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobi, D.; Krashin, E.; Davis, P.J.; Cody, V.; Ellis, M.; Ashur-Fabian, O. Three-Dimensional Modeling of Thyroid Hormone Metabolites Binding to the Cancer-Relevant αvβ3 Integrin: In-Silico Based Study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 895240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.B.; Tang, H.Y.; Shih, A.; Keating, T.; Lansing, L.; Hercbergs, A.; Fenstermaker, R.A.; Mousa, A.; Mousa, S.A.; Davis, P.J.; et al. Acting via a Cell Surface Receptor, Thyroid Hormone Is a Growth Factor for Glioma Cells. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 7270–7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, S.; Yamabe, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Konno, T.; Tada, K. Establishment and Characterization of a Human Acute Monocytic Leukemia Cell Line (THP-1). Int. J. Cancer 1980, 26, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, E.; Sabellico, C.; Hájek, J.; Staňková, V.; Filipský, T.; Balducci, V.; De Vito, P.; Leone, S.; Bavavea, E.I.; Silvestri, I.P.; et al. Protection of Cells against Oxidative Stress by Nanomolar Levels of Hydroxyflavones Indicates a New Type of Intracellular Antioxidant Mechanism. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, J.Z.; Oliveira, C.; Incerpi, S.; Kumar, V.; Fiore, A.M.; De Vito, P.; Prasad, A.K.; Malhotra, S.V.; Parmar, V.S.; Saso, L. Antioxidant Activity of 4-Methylcoumarins. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 1721–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasi, E.; Barluzzi, R.; Bocchini, V.; Mazzolla, R.; Bistoni, F. Immortalization of Murine Microglial Cells by a V-Raf / v-Myc Carrying Retrovirus. J. Neuroimmunol. 1990, 27, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Tao, X.; Cheng, H. Ammonia-Containing Dimethyl Sulfoxide: An Improved Solvent for the Dissolution of Formazan Crystals in the 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-Yl)-2,5- Diphenyl Tetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Assay. Anal. Biochem. 2012, 421, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.C.; Park, A.Y.; Guan, J.L. In Vitro Scratch Assay: A Convenient and Inexpensive Method for Analysis of Cell Migration in Vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurenzi, M.A.; Arcuri, C.; Rossi, R.; Marconi, P.; Bocchini, V. Effects of Microenvironment on Morphology and Function of the Microglial Cell Line BV-2. Neurochem. Res. 2001, 26, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomba, L.; Persichini, T.; Mazzone, V.; Colasanti, M.; Cantoni, O. Inhibition of Nitric-Oxide Synthase-I (NOS-I)-Dependent Nitric Oxide Production by Lipopolysaccharide plus Interferon-γ Is Mediated by Arachidonic Acid: Effects on NFκB Activation and Late Inducible NOS Expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 29895–29901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridnour, L.A.; Sim, J.E.; Hayward, M.A.; Wink, D.A.; Martin, S.M.; Buettner, G.R.; Spitz, D.R. A Spectrophotometric Method for the Direct Detection and Quantitation of Nitric Oxide, Nitrite, and Nitrate in Cell Culture Media. Anal. Biochem. 2000, 281, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).