Submitted:

23 July 2024

Posted:

24 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

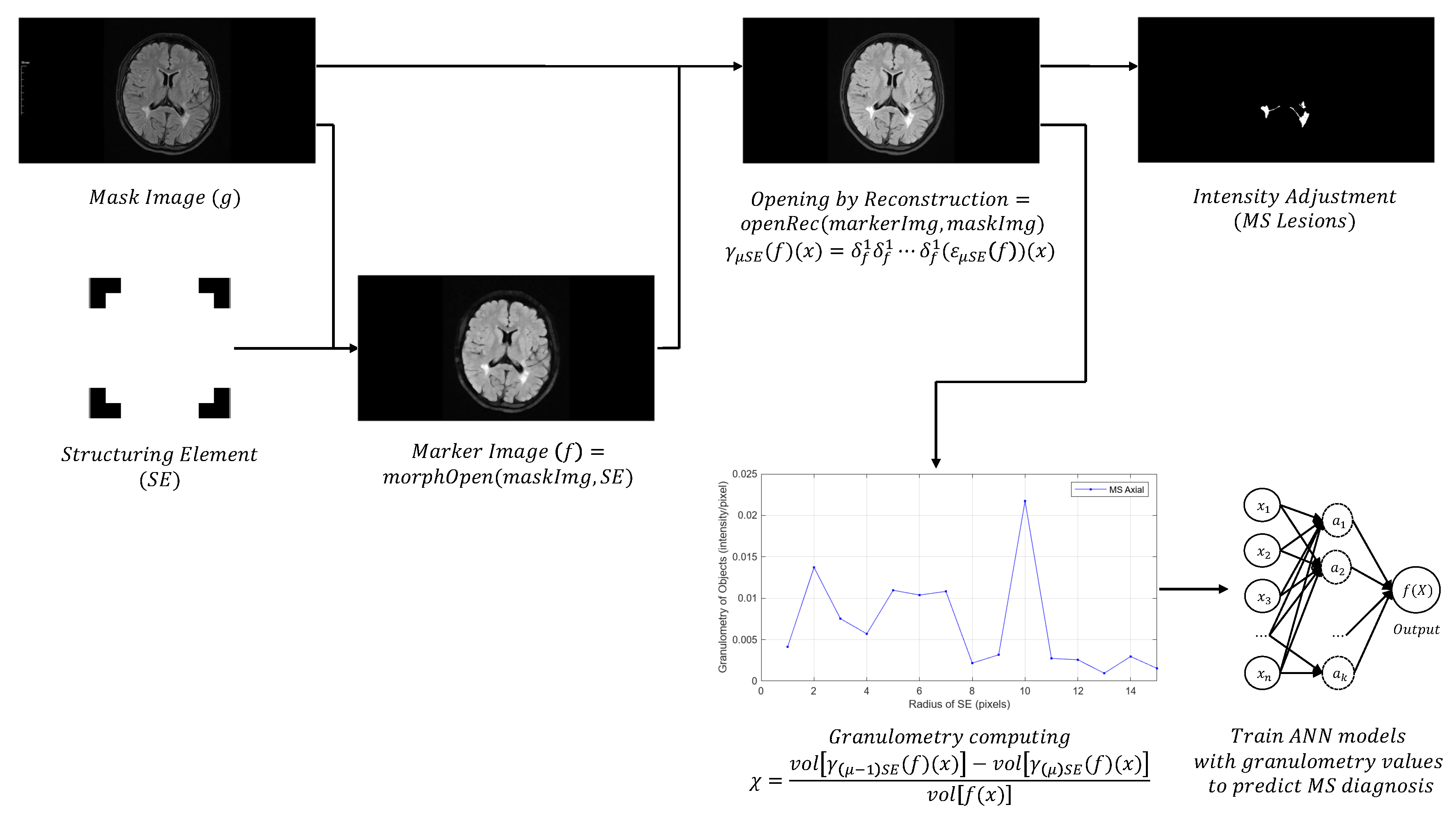

- Perform morphological opening transformations on brain MRI (MS patients and healthy individuals diagnosed by medical experts), to delete noise and other undesirable components. Also, to compute the granulometry of objects in MRI to characterize the demyelination lesions in the brain white matter caused by MS, and use the resulting data for training two artificial neural networks (ANN) models to predict the MS diagnosis.

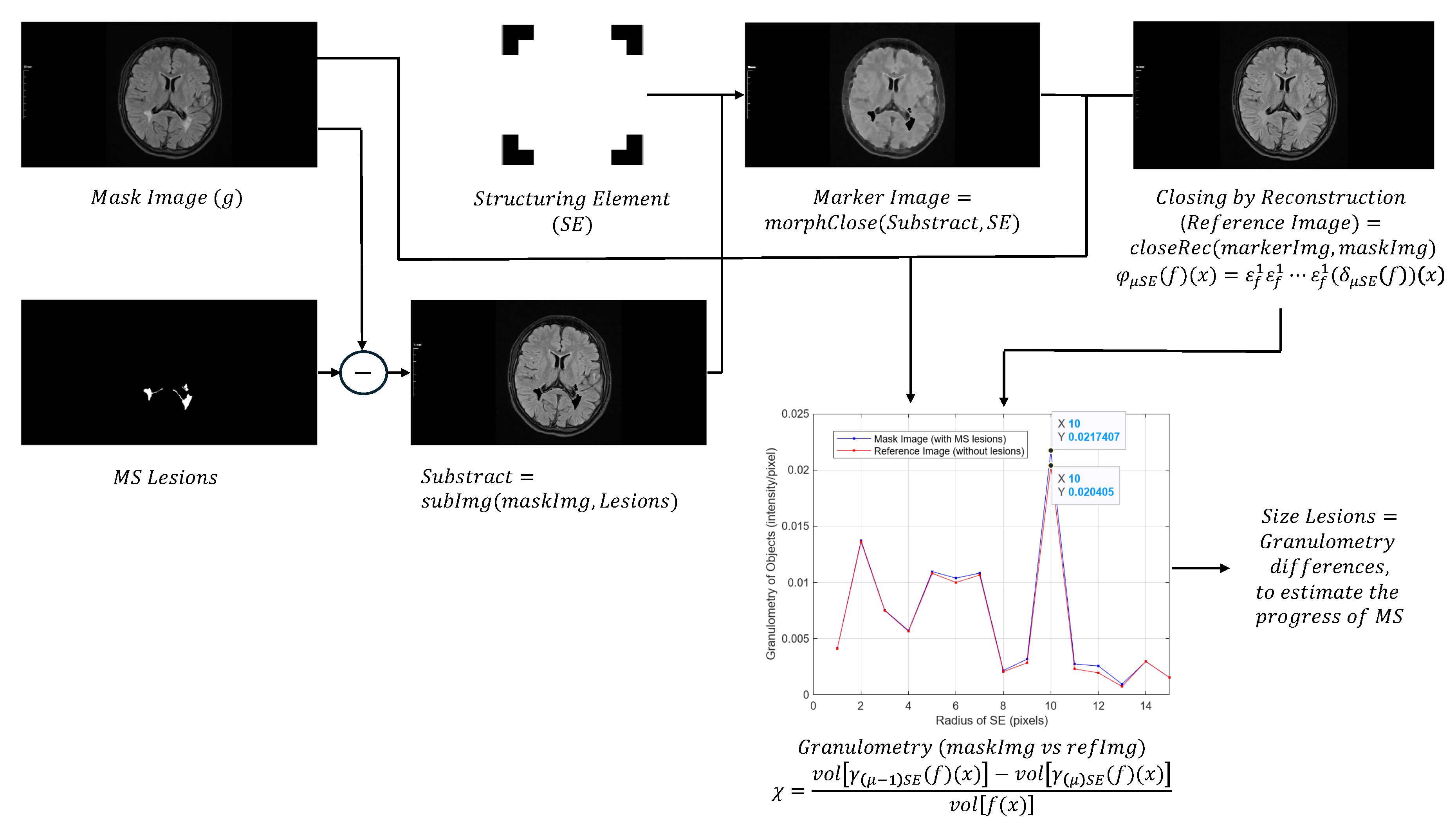

- Perform morphological closing transformations on brain MRI (MS patients), to create a reference image (without lesions) and compute the granulometry of objects of an image with lesions and the reference image to be compared. Then, to determine the size of the MS lesions by calculating the differences in granulometry measurements. These measurements could support the decision of specialists to estimate the course or progress of the disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

2.2. Mathematical Morphology

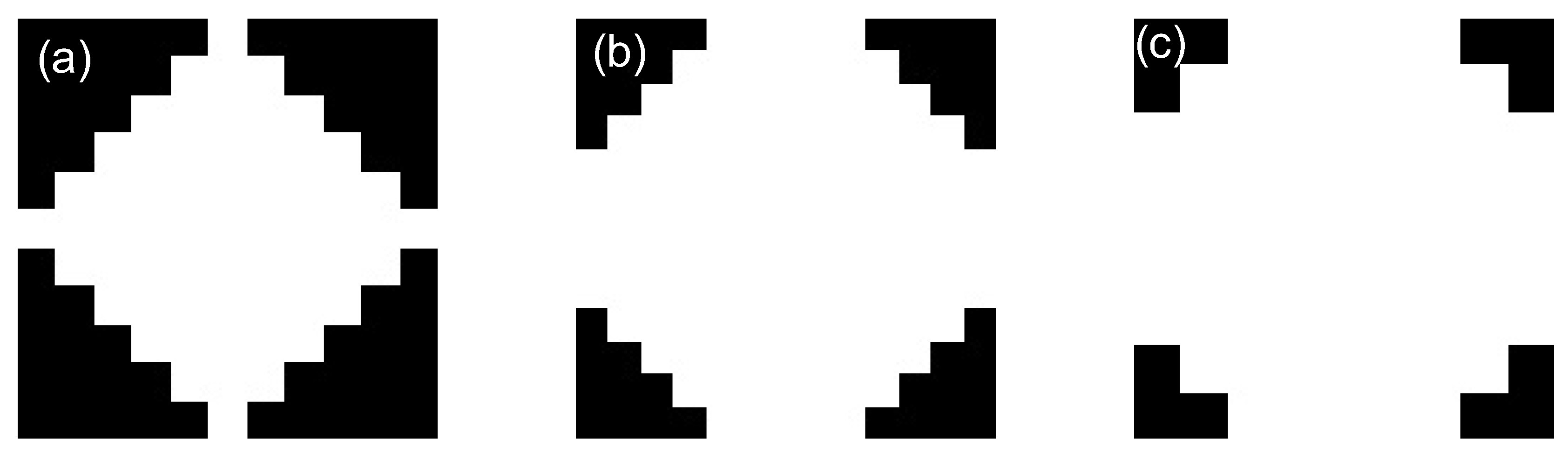

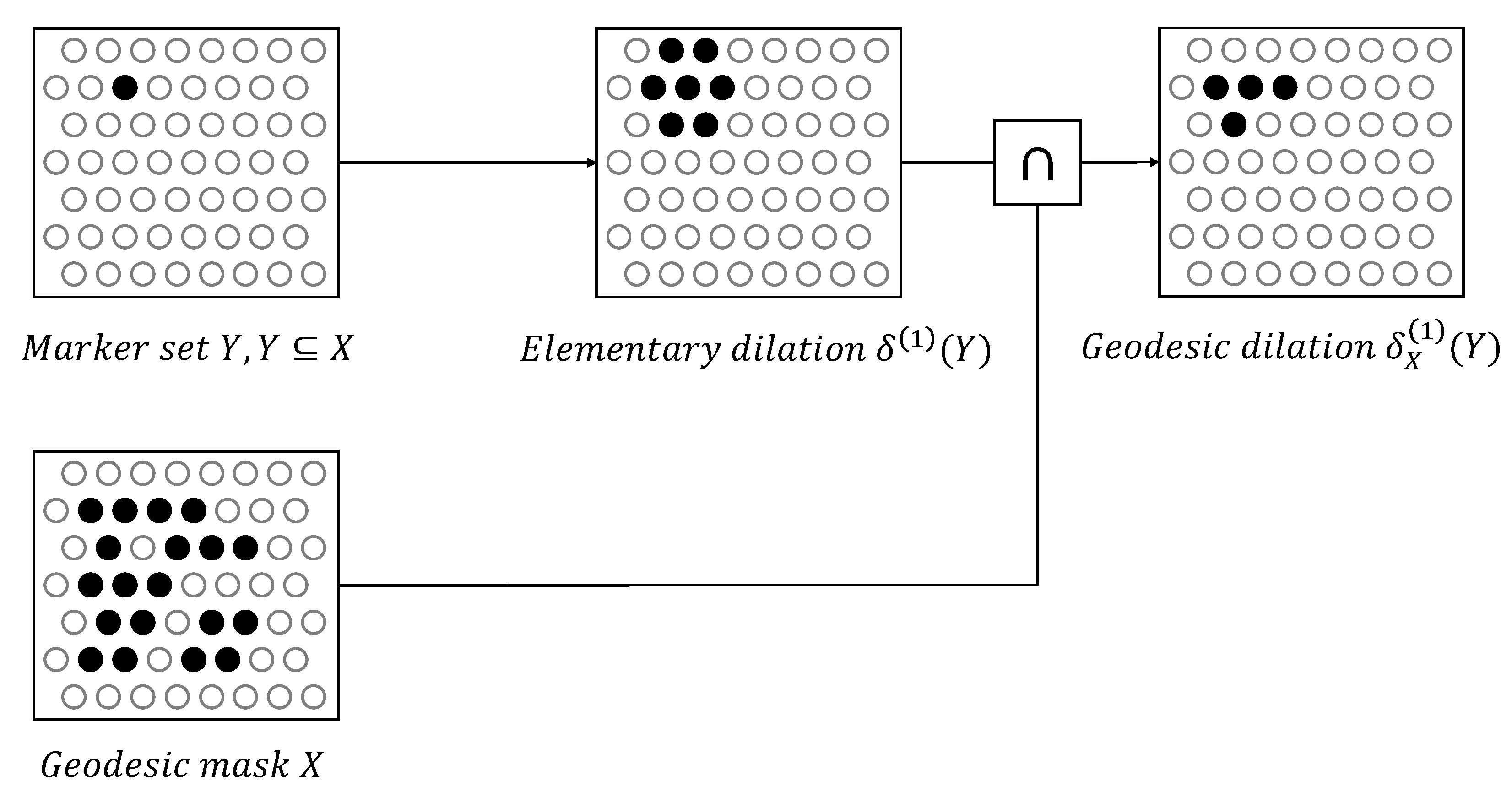

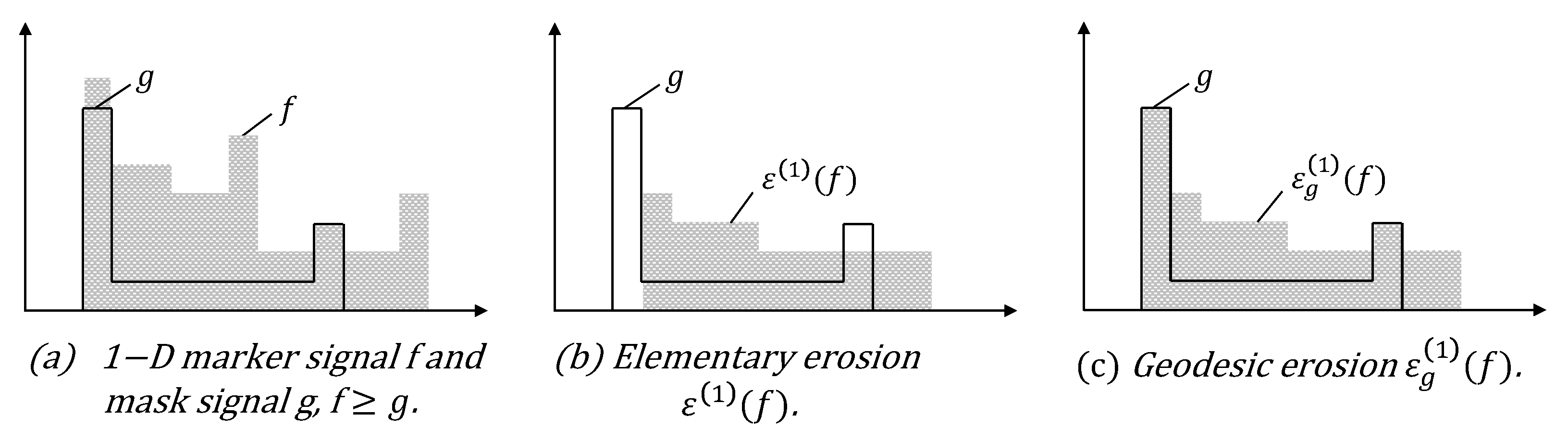

2.3. Geodesic Transformations

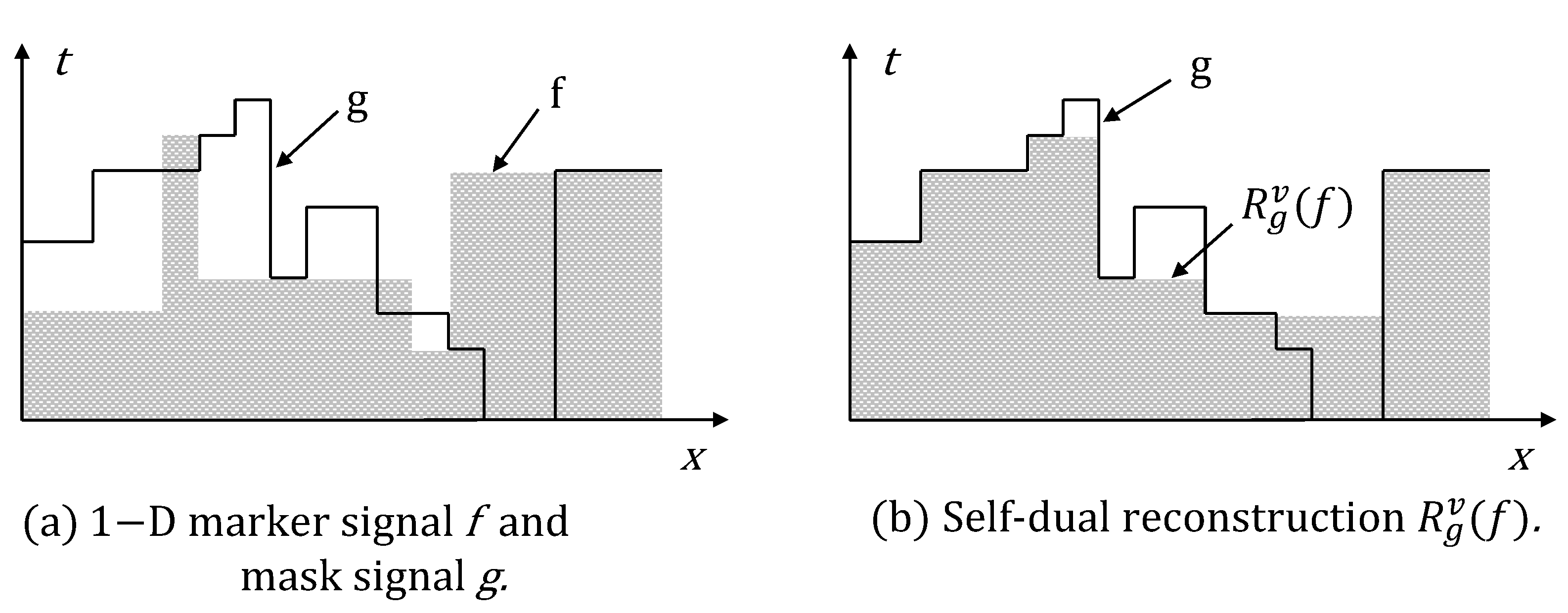

2.4. Morphological Reconstruction

2.4.1. Opening and Closing by Reconstruction

2.5. Image Measurements

2.6. Proposed Algorithm

-

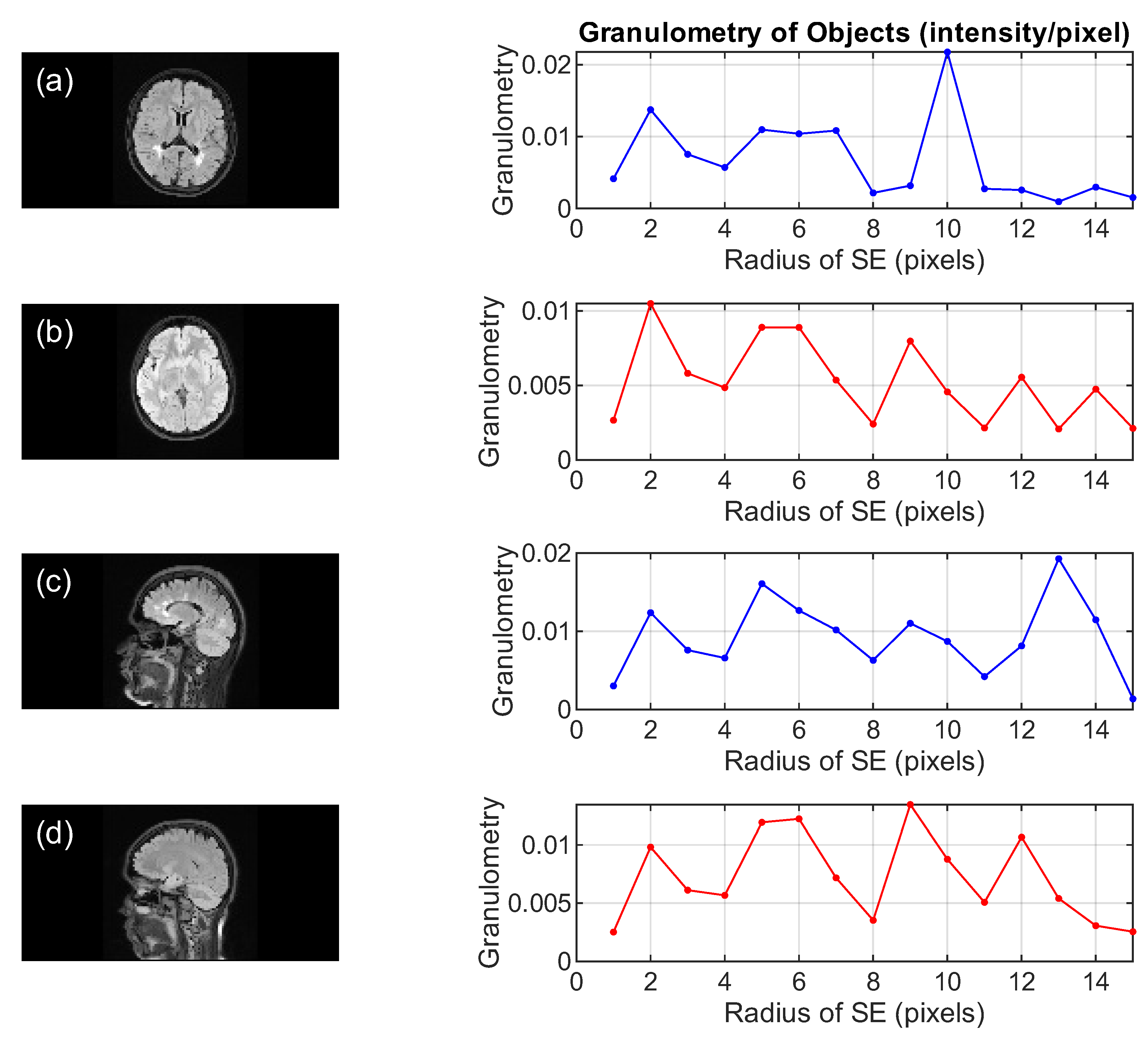

Perform opening morphological transformations on brain images of MS patients and healthy individuals (axial and sagittal MRI), compute the granulometry of objects (Equation 7), and use the resulting data to train two ANN models, applying the following steps:

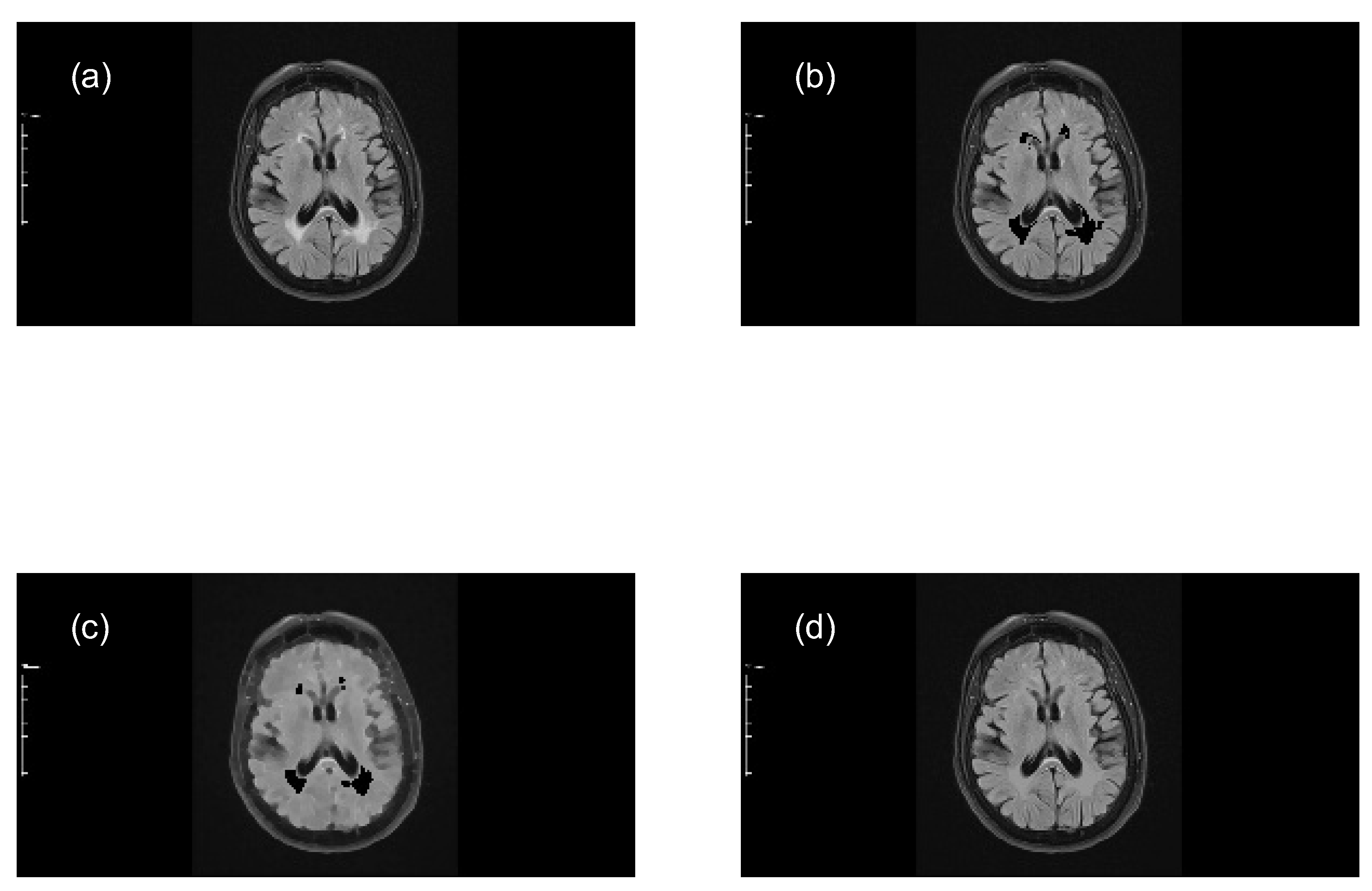

- Read the original color image (.png) and convert it to grayscale (e.g. uint8 array 569x1158x3 → uint8 array 569x1158).

- Perform a morphological opening transformation on the image in grayscale (mask image) to create a marker image using a SE. This operation consists of an erosion followed by a dilation using the same SE. The created SE is disk-shaped with radius r, which matches the geometric properties of the relevant structures of a brain image.

- Perform an opening by reconstruction transformation on the mask image (Equation 5), using the marker image to identify high-intensity objects in the mask image.

- Adjust the intensity values of the opened image by reconstruction, which increases the contrast of the output image, to extract relevant structures (MS lesions).

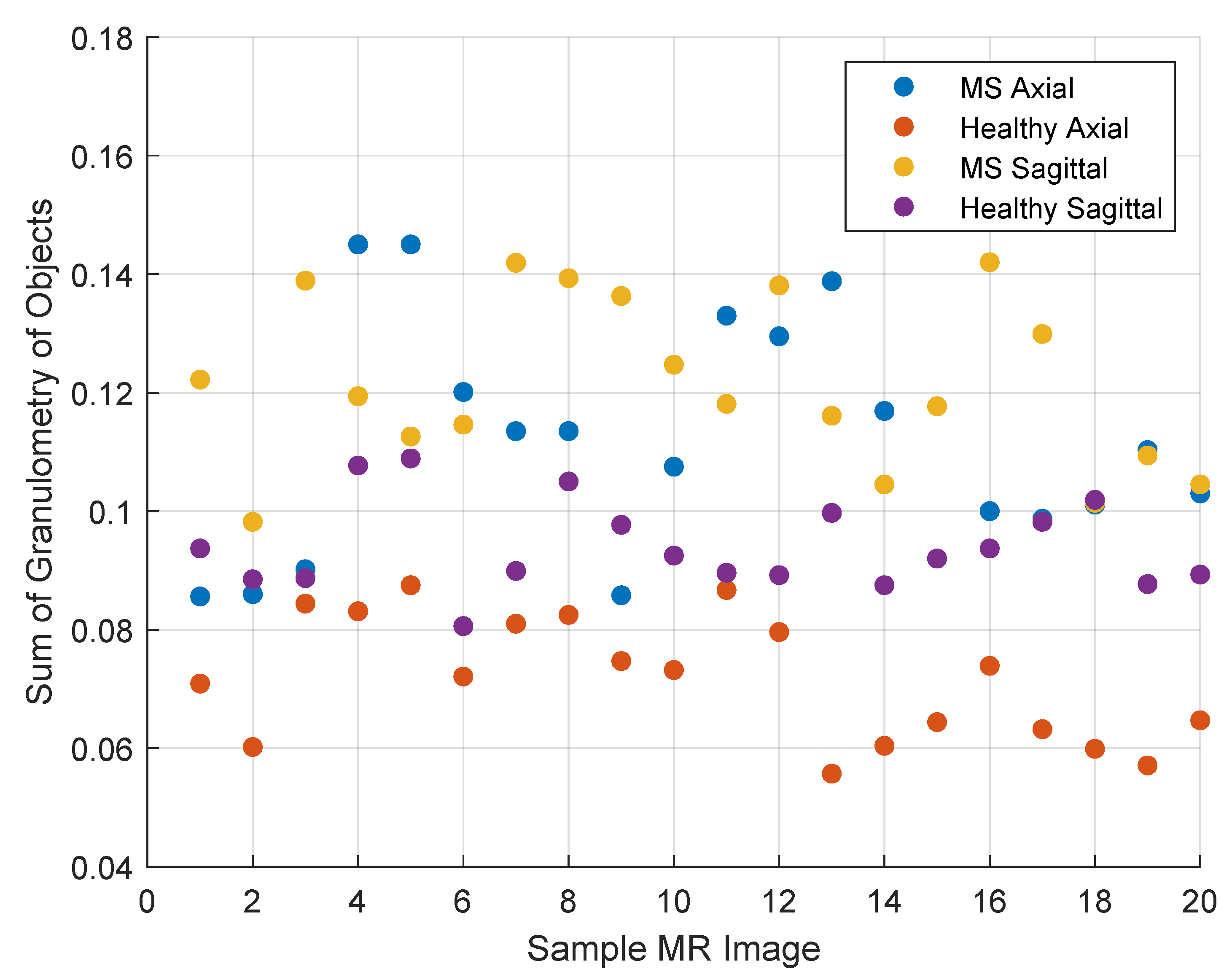

- Compute the granulometry of objects of the opened image by reconstruction for different radius values () of the SE.

- Enter the granulometry measurements of each sample into two arrays (axial and sagittal) of dimension: 100 samples x 15 features (radius values) = 1500 samples for each array.

- Train two ANN models with the granulometry measurements, using MATLAB R2023a software, to make predictions of MS diagnosis.

-

Perform closing morphological transformations on brain images of MS patients (axial and sagittal MRI) to determine the size of the MS lesions, applying the following steps:

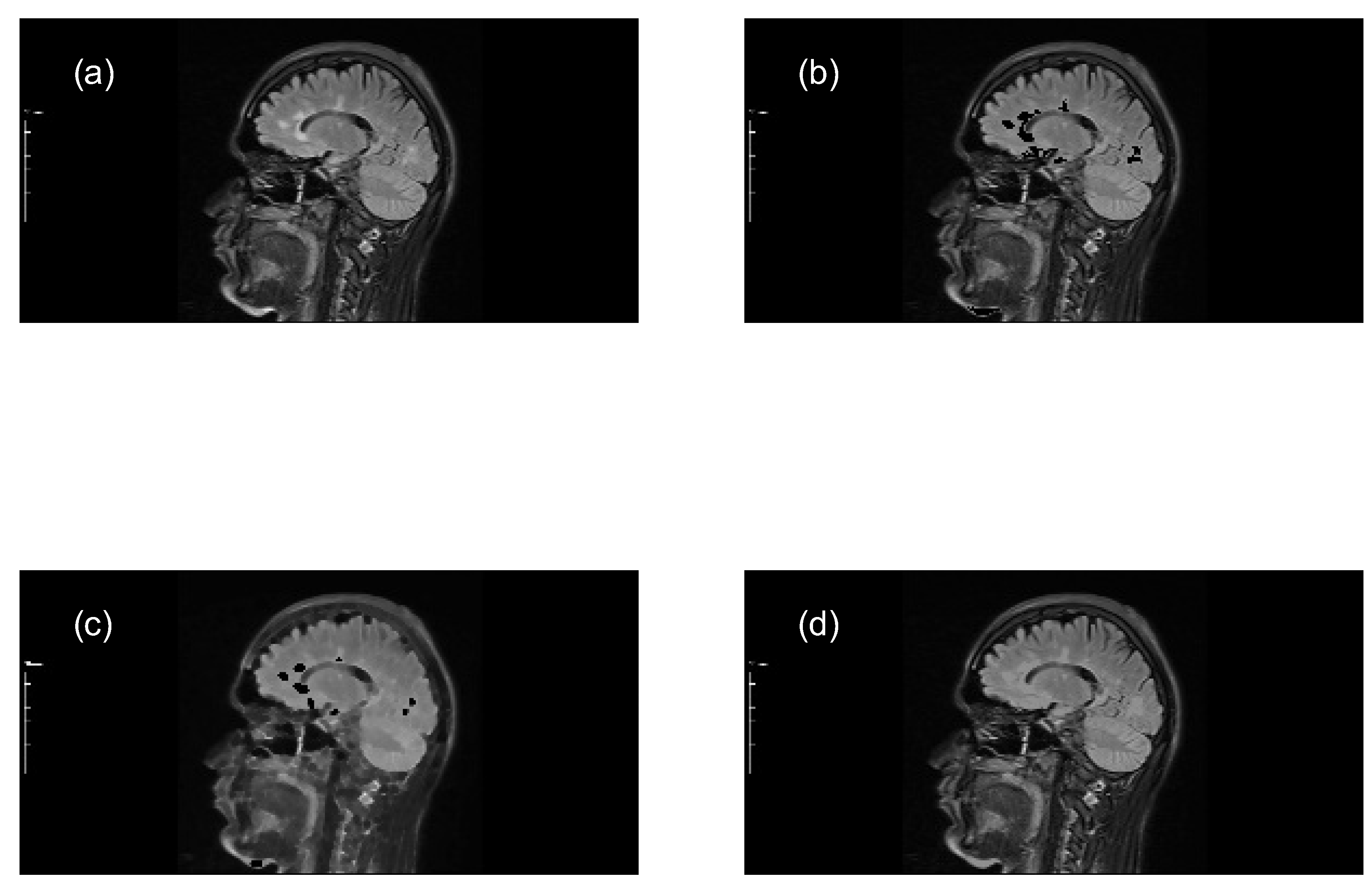

- Subtract the lesion areas from the mask image (original image) to acquire a brain image without lesions (with holes).

- Perform a morphological closing transformation on the resulting image (previous step) using a disk-shaped SE with radius r to create a marker image. This operation consists of a dilation followed by erosion using the same SE.

- Perform a closing by reconstruction transformation on the marker image (Equation 6), using the mask image to fill the holes and create a reference image (without lesions), for making comparisons with the mask image (with lesions).

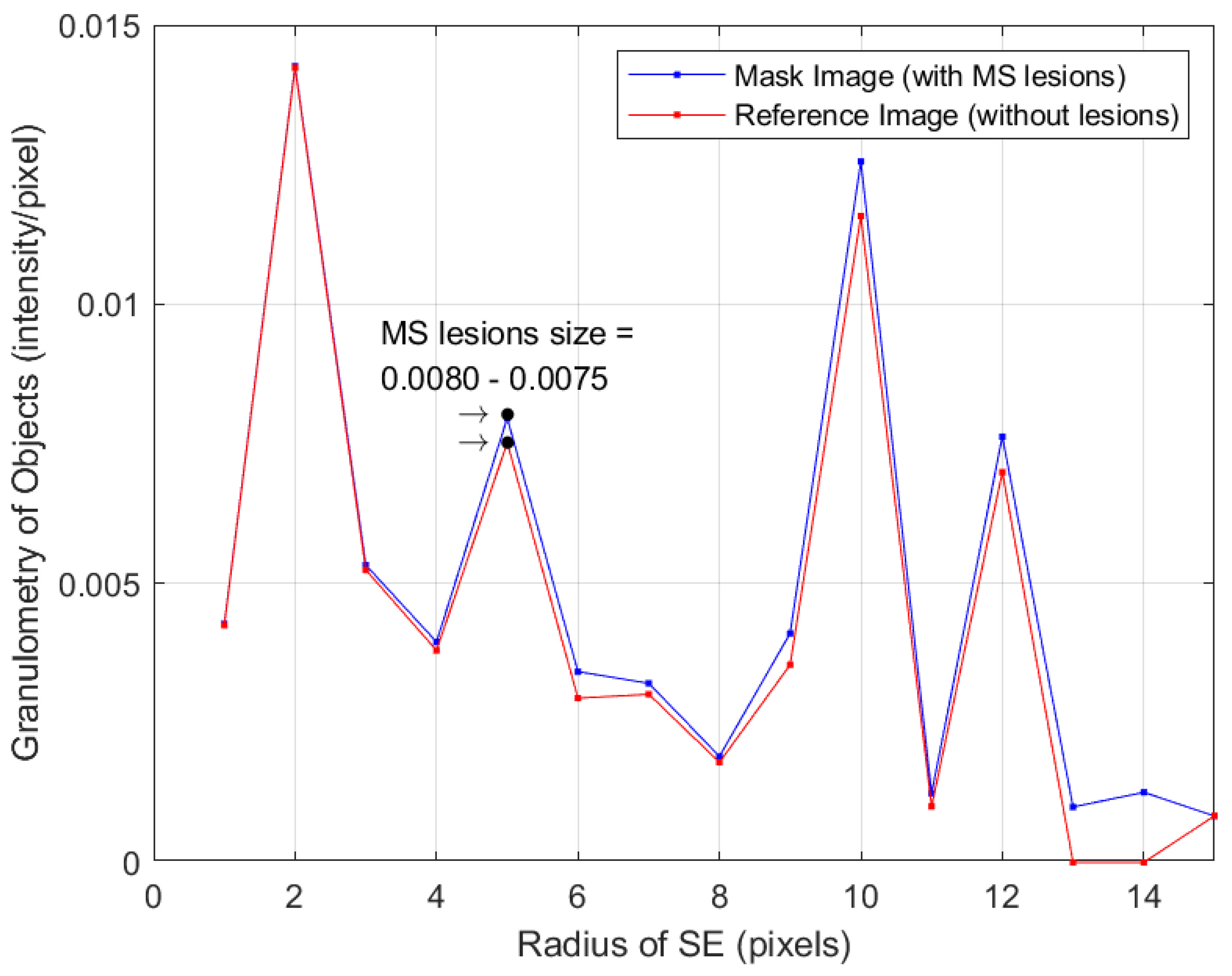

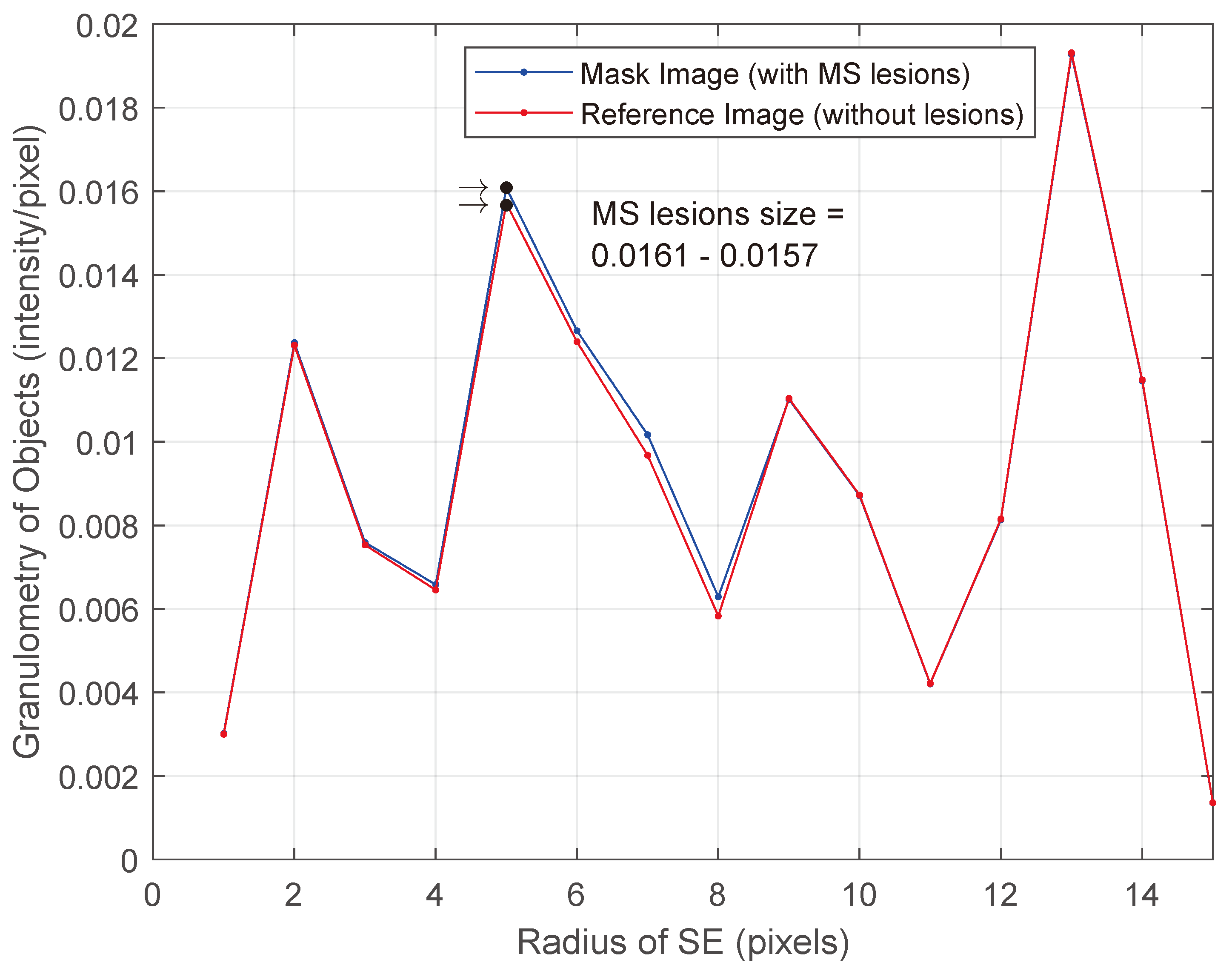

- Compute the granulometry of objects of the mask image and the reference image for different values of radius () of the SE.

- Determine the size of MS lesions by computing the differences in granulometry measurements of the mask image and the reference image to support the decision of specialists in estimating the disease progress.

2.6.1. Artificial Neural Network

3. Results

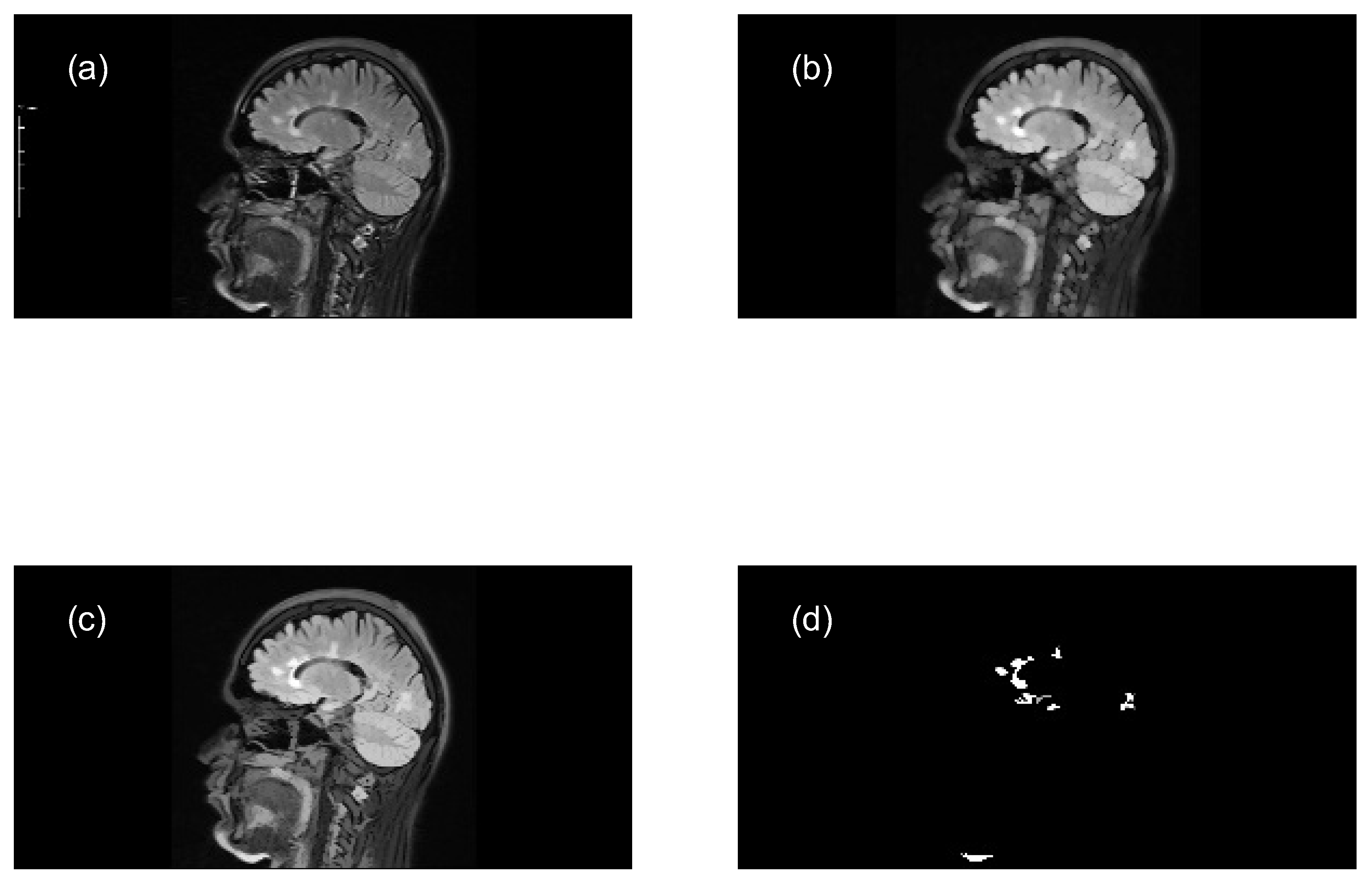

3.1. Algorithm (Stage 1)

3.2. Algorithm (Stage 2)

4. Discussion

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MM | Mathematical morphology |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| RF | Radiofrequency |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| FLAIR | Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| CEN | Convolutional encoder network |

| GAN | Generative adversarial network |

| MP2RAGE | Magnetization prepared 2 rapid acquisition gradient echoes |

| UNI | Uniform image |

| HHO | Harris hawks optimization |

| ML | Machine learning |

| LPQ | Local phase quantization |

| ExMPLPQ | Exemplar multiple parameters local phase quantization |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| FCM | Fuzzy c-means |

| SE | Structuring element |

| DSC | Dice similarity coefficient |

| TPR | True positive rate |

| TNR | True negative rate |

References

- Fernández, O., Fernández, V., E., Guerrero, M. Esclerosis múltiple. Medicine, Programa de Formación Médica, 2015, 11(77), 4610-4621.

- Milo, R., & Miller, A. Revised diagnostic criteria of multiple sclerosis. Autoimmunity reviews, 2014, 13(4-5), 518-524. [CrossRef]

- Lassmann, H., Brück, W., Lucchinetti, C. F. The immunopathology of multiple sclerosis: an overview. Brain pathology, 2007, 17(2), 210-218. [CrossRef]

- Murray, T. J. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis. Bmj, 2006, 332(7540), 525-527. [CrossRef]

- Hočevar, K., Ristić, S., Peterlin, B. Pharmacogenomics of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Frontiers in neurology, 2019, 10, 134. [CrossRef]

- Lladó, X., Oliver, A., Cabezas, M., Freixenet, J., Vilanova, J. C., Quiles, A., Rovira, À. Segmentation of multiple sclerosis lesions in brain MRI: a review of automated approaches. Information Sciences, 2012, 186(1), 164-185. [CrossRef]

- Wildner, P., Stasiołek, M., Matysiak, M. Differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and other inflammatory CNS diseases. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders, 2020, 37, 101452. [CrossRef]

- Katti, G., Ara, S. A., Shireen, A. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–A review. International journal of dental clinics, 2011, 3(1), 65-70.

- Macovski, A. Noise in MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 1996, 36(3), 494-497.

- Hendee, W. R., & Ritenour, E. R. Fundamentals of magnetic resonance. Medical imaging physics, 2002, NY: Wiley-Liss, 355-365.

- Uyttendaele, M., Eden, A., Skeliski, R. Eliminating ghosting and exposure artifacts in image mosaics. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2001, 2, II-II.

- Liu, X., Song, L., Liu, S., Zhang, Y. A review of deep-learning-based medical image segmentation methods. Sustainability, 2021, 13(3), 1224. [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, A., Rahim, M. S. M., Altameem, A., Saba, T., Rad, A. E., Rehman, A., Uddin, M. Medical image segmentation methods, algorithms, and applications. IETE Technical Review, 2014, 31(3), 199–213. [CrossRef]

- de Arruda, A. L. C., Vital, D. A., Kitamura, F. C., Abdala, N., Moraes, M. C. Multiple sclerosis segmentation method in magnetic resonance imaging using fuzzy connectedness, binarization, mathematical morphology, and 3D reconstruction. Research on Biomedical Engineering, 2020, 36, 291-301. [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Wu, G.; Suk, H.I. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng., 2017, 19, 221–248.

- Ghosh, S., Huo, M., Shawkat, M. S. A., McCalla, S. Using convolutional encoder networks to determine the optimal magnetic resonance image for the automatic segmentation of multiple sclerosis. Applied Sciences, 2021, 11(18), 8335. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, F., Yu, T., Barquero, G., Thiran, J. P., Granziera, C., Cuadra, M. B. MPRAGE to MP2RAGE UNI translation via generative adversarial network improves the automatic tissue and lesion segmentation in multiple sclerosis patients. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 2021, 132, 104297. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, R., Kundu, R., Oliva, D., Sarkar, R. Segmentation of brain MRI using an altruistic Harris Hawks’ Optimization algorithm. Knowledge-Based Systems, 2021, 232, 107468. [CrossRef]

- Macin, G., Tasci, B., Tasci, I., Faust, O., Barua, P. D., Dogan, S., Acharya, U. R. An accurate multiple sclerosis detection model based on exemplar multiple parameters local phase quantization: ExMPLPQ. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(10), 4920. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M., Piacenti-Silva, M., da Rocha, F. C. G., Santos, J. M., Cardoso, J. D. S., Lisboa-Filho, P. N. Lesion volume quantification using two convolutional neural networks in MRIs of multiple sclerosis patients. Diagnostics, 2022, 12(2), 230. [CrossRef]

- Acar, Z. Y., Başçiftçi, F., Ekmekci, A. H. Convolutional Neural Network model for identifying Multiple Sclerosis on brain FLAIR MRI. Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems, 2022, 35, 100706. [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M., Akhbari, M., Jutten, C. Delve into multiple sclerosis (MS) lesion exploration: a modified attention U-net for MS lesion segmentation in brain MRI. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 2022, 145, 105402. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Xiao, P., Tan, H. Spinal magnetic resonance image segmentation based on U-net. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences, 2023, 16(3), 100627. [CrossRef]

- Rondinella, A., Crispino, E., Guarnera, F., Giudice, O., Ortis, A., Russo, G., Battiato, S. Boosting multiple sclerosis lesion segmentation through attention mechanism. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 2023, 161, 107021. [CrossRef]

- Bose, A., Maulik, U., Sarkar, A. An entropy-based membership approach on type-II fuzzy set (EMT2FCM) for biomedical image segmentation. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 2024, 127, 107267. [CrossRef]

- Soille, P. Morphological image analysis: principles and applications. Berlin: Springer., 1999, 2(3), 170-171.

- Soille, P. Geodesic transformations. Morphological Image Analysis: Principles and Applications., 2004, Springer, 183-218.

- Santibáñez, J. D. M., Duarte, M. G., Retana, J. J. O., Campos, C. E. L. Segmentación y análisis granulométrico de sustancia blanca y gris en IRM para el estudio del estrabismo usando transformaciones morfológicas. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Biomédica., 2007, 28(2), 13-13.

- Casalino, G., Castellano, G., Consiglio, A., Nuzziello, N., Vessio, G. MicroRNA expression classification for pediatric multiple sclerosis identification. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 2023, 14(12), 15851-15860. [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Li, W.; Vercauteren, T.; Ourselin, S.; Cardoso, M.J. Generalised Dice Overlap as a Deep Learning Loss Function for Highly Unbalanced Segmentations. Springer International Publishing, 2017, 240-248. [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, C. E., McCarroll, R. E., Court, L. E., Elgohari, B. A., Elhalawani, H., Fuller, C. D., Aristophanous, M. (2018). Deep learning algorithm for auto-delineation of high-risk oropharyngeal clinical target volumes with built-in dice similarity coefficient parameter optimization function. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics, 2018, 101(2), 468-478. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M., Khanna, D., Rana, P. S., Khaibullin, T., Martynova, E., Rizvanov, A. A., ... & Baranwal, M. (2019). Computational intelligence technique for prediction of multiple sclerosis based on serum cytokines. Frontiers in neurology, 2019, 10, 781. [CrossRef]

| Pseudocode | ||

|---|---|---|

| Start | ||

| rgb = readImg(’sample’.png) | ||

| grayScale = rgbTogray(rgb) | ||

| maskImg = grayScale | ||

| markerImg1 = morphOpen(maskImg, SE 1(’disk’,5)) | ||

| openRec1 = openRec(markerImg1,maskImg) | ||

| MSlesions = intensityAdjust(openRec1) | ||

| volMaskImg1 = 1.0*sum(maskImg) | ||

| For | radius = 1:15 | |

| markerImg2 = morphOpen(maskImg, SE(’disk’, radius - 1)) | ||

| openRec2 = openRec(markerImg2, maskImg) | ||

| volOpenRec1 = sum(openRec2) | ||

| markerImg3 = morphOpen(maskImg, SE(’disk’, radius)) | ||

| openRec3 = openRec(markerImg3, maskImg) | ||

| volOpenRec2 = sum(openRec3) | ||

| volGranu(radius) = (volOpenRec1-volOpenRec2)/volMaskImg1 | ||

| End |

| Pseudocode | ||

|---|---|---|

| Start | ||

| subtract = imgSub(maskImg, MSLesions) | ||

| markerImg4 = morphClose(subtract, SE(’disk’,radius=5)) | ||

| closeRec1 1 = closeRec(markerImg4,maskImg) | ||

| volMaskImg2 = 1.0*sum(closeRec1) | ||

| For | radius = 1:15 | |

| markerImg5 = morphOpen(closeRec1, SE(’disk’, radius - 1)) | ||

| openRec5 = openRec(markerImg5, closeRec1) | ||

| volOpenRec3 = sum(openRec5) | ||

| markerImg6 = morfOpen(closeRec1, SE(’disk’, radius)) | ||

| openRec6 = openRec(markerImg6, closeRec1) | ||

| volOpenRec4 = sum(openRec6) | ||

| volGranu(radius) = (volOpenRec3-volOpenRec4)/volMaskImg2 | ||

| End |

| Model | Activations | Standardize | Lambda | LayerSizes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (default) | (enabled) | (adjusted) | (default) | |

| ANN (axial) | ’relu’ | true | 0.005 | 10 |

| ANN (sagittal) | ’relu’ | true | 0.02 | 10 |

| Sample | r=1 | r=2 | r=3 | ... | r=15 | Diagnostic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0044 | 0.014 | 0.006 | ... | 0 | MS_Axial |

| 2 | 0.0038 | 0.0135 | 0.0087 | ... | 0.0176 | MS_Axial |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||

| 50 | 0.0029 | 0.0108 | 0.0063 | ... | 0.0082 | MS_Axial |

| 51 | 0.0021 | 0.0075 | 0.0045 | ... | 0.0016 | Healthy_Axial |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||

| 99 | 0.0023 | 0.009 | 0.0061 | ... | 0.0023 | Healthy_Axial |

| 100 | 0.0022 | 0.0089 | 0.0058 | ... | 0.0006 | Healthy_Axial |

| Sample | r=1 | r=2 | r=3 | ... | r=15 | Diagnostic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0025 | 0.099 | 0.006 | ... | 0.0017 | MS_Sagittal |

| 2 | 0.0018 | 0.0073 | 0.0044 | ... | 0.0024 | MS_Sagittal |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||

| 50 | 0.003 | 0.0124 | 0.0074 | ... | 0.0037 | MS_Sagittal |

| 51 | 0.0022 | 0.009 | 0.0052 | ... | 0.0014 | Healthy_Sagittal |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ||||

| 99 | 0.0019 | 0.0076 | 0.0042 | ... | 0.0019 | Healthy_Sagittal |

| 100 | 0.002 | 0.0082 | 0.0049 | ... | 0.0017 | Healthy_Sagittal |

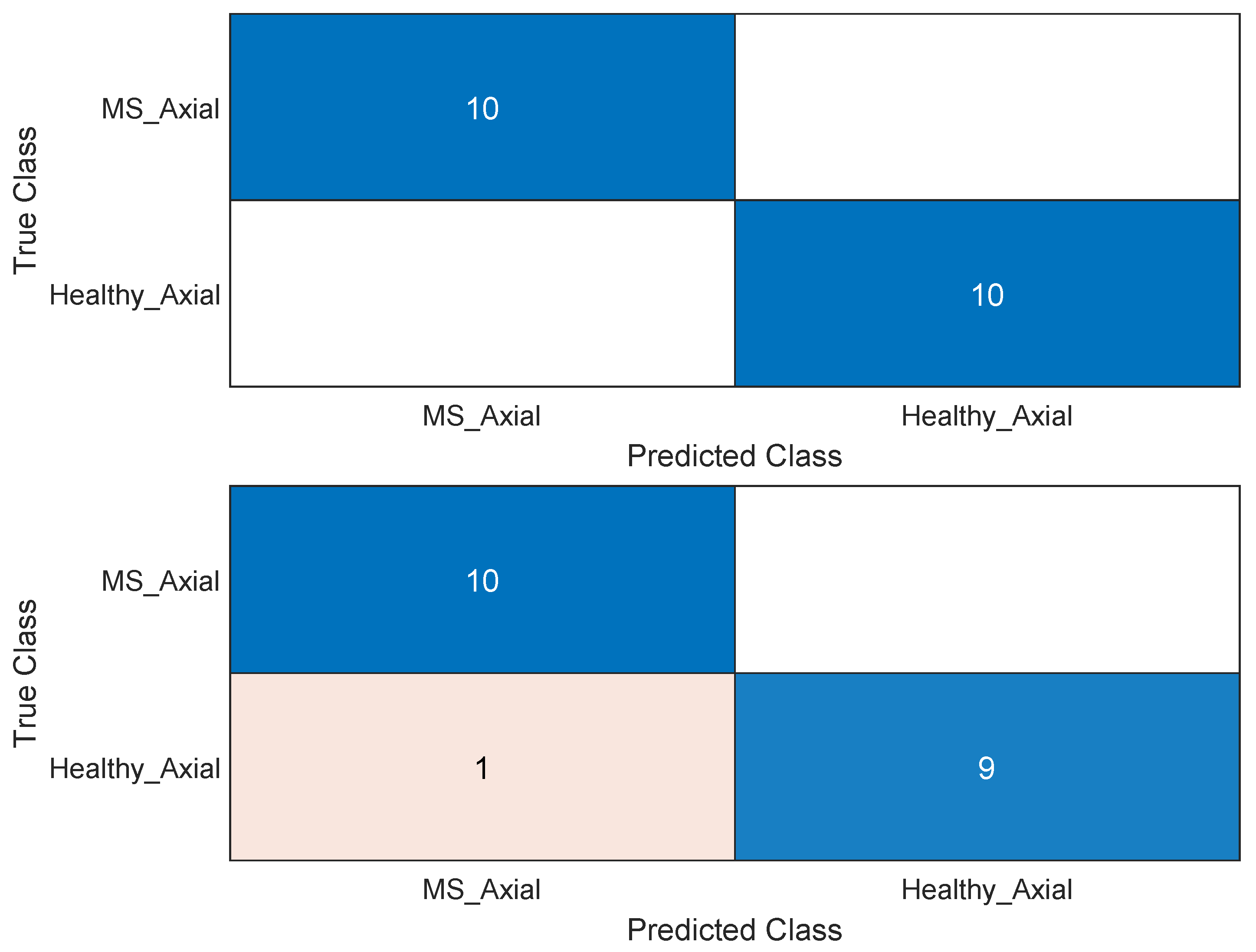

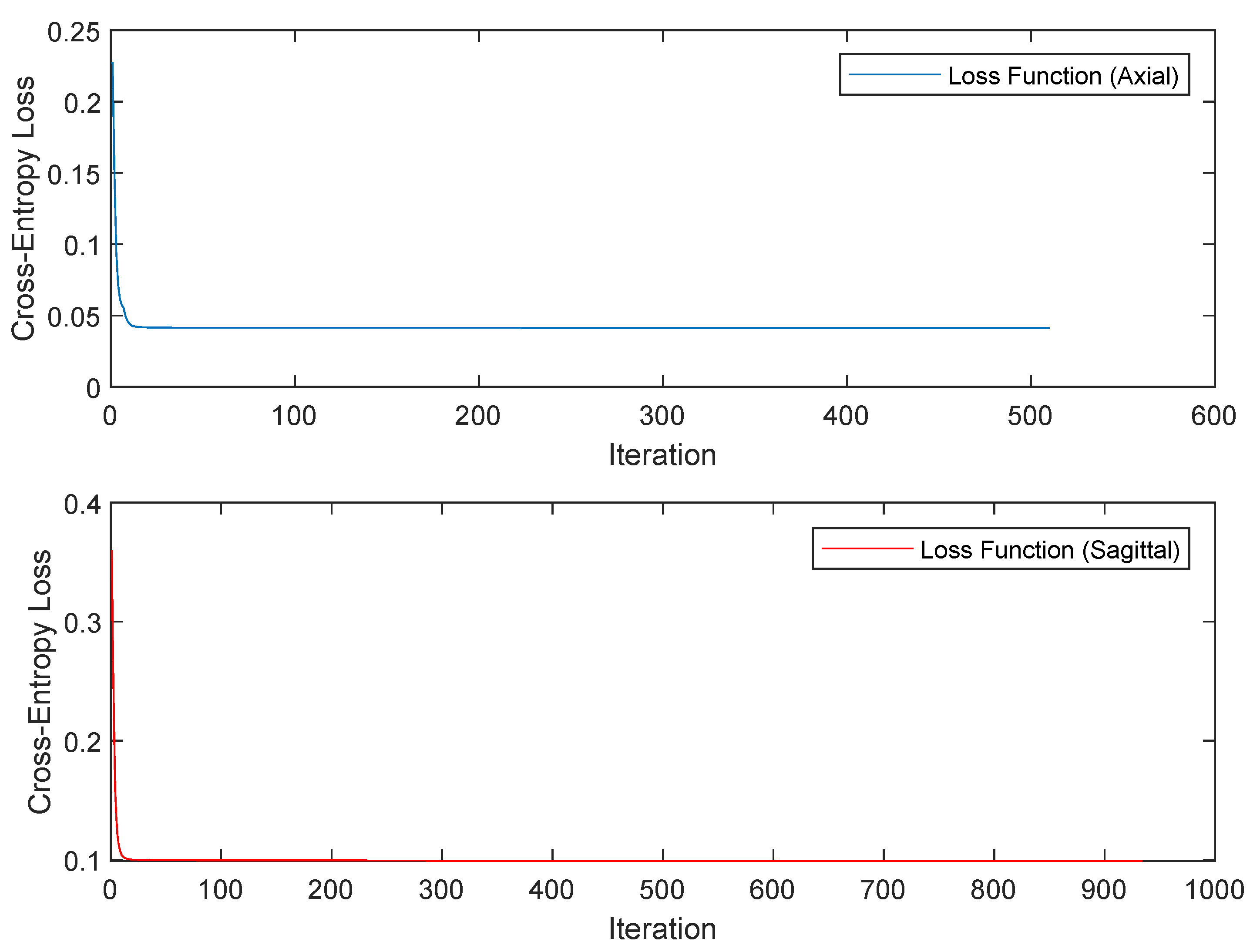

| Model | Test Accuracy | DSC 1 | TPR 2 | TNR 3 | Cross-Entropy Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANN (axial) | 0.9753 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0247 |

| ANN (sagittal) | 0.9345 | 0.9523 | 0.909 | 1.0 | 0.0655 |

| Image | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Autor | Processing | Classifier | Performance |

| Technique | |||

| [16] | CEN | U-Net, U-Net++ | 0.7159 1 |

| Linknet | |||

| [19] | ExMPLPQ | kNN | 0.9837 3 |

| 0.9775 4 | |||

| [20] | Lesion volume | CNN | 0.9786 1 |

| quantification | 0.9969 2 | ||

| [21] | CNN | CNN | 0.98 5 |

| 0.903 6 | |||

| [22] | Attention | Modified | 0.823 1 |

| U-Net | U-Net | ||

| [23] | U-Net | U-Net++ | 0.88 1 |

| [24] | Augmented U-Net | LSTM | 0.89 1 |

| Our paper | Morphology & | ANN | 1.0 1 |

| Granulometry | 0.9654 3 | ||

| 0.9437 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).