1. Introduction

This research aims to theoretically calculate and simulate the forces that can cause a change in the shape of a DNA-like double helix in its various regions in the presence of an electromagnetic wave. Whether disruptive forces are possible under conditions of half-wave resonance in an external electromagnetic field is the subject of discussion. The inquiry also concerns the specific regions within the double helix where these forces might exert their impact, as well as the timing of their emergence. And, for this purpose, the forces acting between the strands of a double helix in the center of the helix, as well as at its edges, are considered.

These issues are relevant, first of all, for the helical elements of metamaterials and metasurfaces. The prospects of using double DNA-like helices as elements of metamaterials are due to several factors. Firstly, such helical elements make it possible to create metamaterials with both dielectric and magnetic properties. Secondly, the symmetry of the distribution of electric currents and charges in a double helix has a higher order compared to a similar distribution in a single helix. Thirdly, double DNA-like helices exhibit special electromagnetic properties, consisting in the equal importance of their electric dipole moment and magnetic moment. This interconnectedness of moments occurs with any electric currents, for example, with conduction currents in metal helices and with polarization currents in dielectric helices. At the same time, it is important that both dielectric and magnetic moments be created within the same helical element; therefore, there is no need to use both straight conductors and ring conductors, which pose challenges in achieving mutual compatibility. These promising properties are manifested in double DNA-like helices, even if their geometric dimensions are changed proportionally compared to real DNA. In other words, the helices can be scaled while maintaining the pitch angle. This allows achieving resonant excitation of the helices in the required wavelength range of the electromagnetic field. The DNA molecule is significant not only as an object and a means of storing genetic information, as demonstrated by scientific research. Our objective is to highlight the unique and exceptional properties exhibited by double DNA-like helices in external electromagnetic fields (Semchenko et al., 2022; Semchenko & Khakhomov, 2023).

Last but not least, the issues of changing the shape or maintaining stability in external electromagnetic fields are also relevant for real DNA. In this paper, a twenty-and-a-half-turn double DNA-like helix is simulated in the electromagnetic field of an incident electromagnetic wave. The selection of the number of turns, namely the length of the helix under study, is influenced by two factors.

First, empirical evidence indicates that the DNA molecule exhibits an absorption band within the UV range near the wavelength λres=280 nm (Ploeser & Loring, 1949; Voet et al., 1963; Konev & Volotovsky, 1979). Such absorption can excite a significant polarization current in the helices since the absorbing centers (atoms and molecules) are in periodic arrangement along the full length of the two helical strands. Through the process of wave interaction, the atoms and molecules that possess the ability to absorb light are capable of generating a specific effective current along the entire helix. Resonance is possible for the electric current in the helix and, consequently, for the forces acting on the helix in the field of an incident wave when the length of the straightened conductor is equal to an integer number of half-waves, i.e., for integer values of n. When n=1, "main" or half-wave resonance is feasible. Here, the length of the helix can be expressed as , where is the number of turns of the helix and P represents the length of one complete turn. Since the length of a single turn of the DNA helix is P=7.14 nm (Jd, 1953, Watson et al., 2013), segments of the DNA molecule that encompass , i.e., roughly 20 turns, can meet the requirement for half-wave resonance and experience activation when exposed to an electromagnetic wave. Segments of this particular length are advantageous for the purpose of direct sequencing and subsequent use in experimental and practical applications.

Secondly, there is a particular focus on DNA segments that comprise around 20 turns due to their potential as nanoconductors, facilitating the flow of low-frequency electric current (Wohlgamuth et al., 2013). It is important to emphasize that a definitive conclusion regarding the electrical conductivity of the DNA molecule has not yet been reached. This is due to the fact that the molecule demonstrates vastly different conductive properties under various conditions, such as those of an insulator, a conductor, and a semiconductor (Wohlgamuth et al., 2013; Eley & Spivey, 1961; Snart, 1973; Tran et al., 2000; Warman et al., 1996; Dewarrat, 2002; Fink & Schönenberger, 1999; Cai et al., 2000; Yoo et al., 2001; Porath et al., 2000; Kasumov et al., 2001; Legrand et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2002; Guo et al., 2008; Gomez-Navarro et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2024; Fink, 2000; Mallajosyula & Pati, 2010; Hodzic et al., 2007; Wang, 2008; Charra et al., 2013). However, direct measurements of the electric current along a fragment of the DNA molecule (Wohlgamuth et al., 2013) revealed that the electric current along the nucleotide sequence decays rather slowly. Therefore, activation of the electric current by an electromagnetic wave is possible in a DNA segment with approximately 20 turns at half-wave resonance.

This study examines the linear state of the DNA molecule, which coexists with the supercoiled and relaxed states (Travers & Muskhelishvili, 2005). The publications (Dharmadhikari et al., 2014; D’Souza et al., 2011; Baccarelli et al., 2011) considered several potential mechanisms for the transition of a DNA molecule between these states, encompassing transitions facilitated by electrons or intense infrared radiation. Transitions of this nature can arise due to ruptures in either or both strands that constitute the double helical structure of the DNA molecule.

Our task is to study the forces that can arise in the field of an electromagnetic wave when it is resonant. Such forces can lead to a change in the shape of the double helix, as well as the previously studied effect of electrons and intense infrared radiation (Dharmadhikari et al., 2014; D’Souza et al., 2011; Baccarelli et al., 2011).

2. Theoretical Calculation of Forces in a Double DNA-like Helix in the Field of an Electromagnetic Wave in a Long Wavelength Approximation

The force acting on the electric current element

in the second strand in a pair of helices can be calculated as follows

where the magnetic field induction vector

is calculated based on the Biot-Savart law and takes into account the magnetic fields created by all elements of the first strand in a pair of helices. A detailed method for calculating these magnetic forces is described in work (Semchenko et al., 2020).

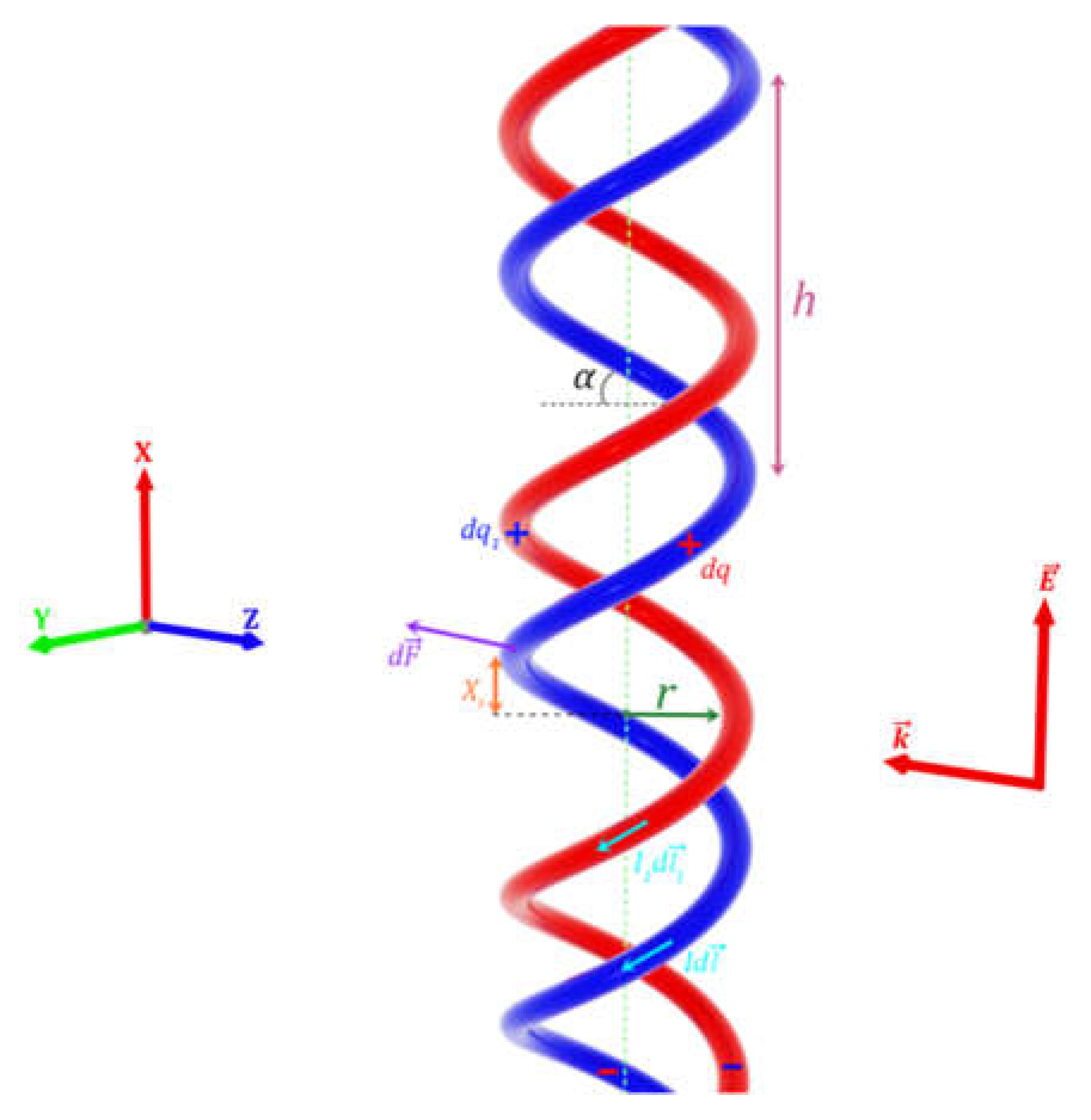

In

Figure 1, the DNA-like helix is schematically represented with its parameters: helix pitch h, helix radius r, axial shift between helices xs, as well as induced charges

,

and induced currents

and

. The direction of the currents in two helices depends on the way of exciting the double helix. In our case, the currents pass in same direction relative to the axis of the helix. The charges and the currents are distributed along the helix as they are induced by harmonic standing wave. The wavelength of the electromagnetic field in vacuum

satisfies the inequality

, where

is the period of the helix (the entire length of one turn of the helix). A very important characteristic of the helix is its pitch angle

, which satisfies the following ratios

,

,

.

Any physically small element of a single-stranded helix is affected by a magnetic force due to the existence of an electric current in this element of the helix. After calculation, we arrive at the following x-, y- and z-components of the magnetic force (1):

Here, the index t means time averaging; the integration variable

is equal to the polar angle for the first helix;

;

is the helix specific torsion, which is positive (

) for a right-handed helix and negative (

) for a left-handed helix;

is the general normalization constant for the force components;

is the amplitude of the standing wave of the current; there is also notation to reduce the formulas to a more compact form:

In addition to the magnetic force, there is also an electric force acting on the electric charges in the second strand in a pair of helices from the side of the entire first strand in a pair of helices. The force acting on the element of electric charge

in the second helix has the following form

where

is the volumetric electric charge density,

is the volume element of the second helix,

is the length element of the second helical strand,

is the effective cross-sectional area of the strand,

is the electric field strength. Vector

is determined by Coulomb's law and must be calculated by integrating the electric fields generated by all elements of the first helix at the location of the selected element of the second helix.

Using the integration technique described in (Semchenko et al., 2020), let us calculate all the components of the electric force (6) acting on the charge element in the second helix from the side of the entire first helix. The calculations result in obtaining the x-, y- and z-components of the force (6), averaged over time:

When calculating forces (2-4), (7-9), integration is performed within infinite limits. However, the formulas for forces can also be applied to a finite helix having a long length. This is due to the property of integrand functions, which decrease rapidly as the variable increases due to the presence of the function in the denominator.

The considered DNA-like helices have a finite length, like the actual DNA molecule. Therefore, a standing wave of electric current is established in each helical strand due to the reflection of waves from the edges of the strands. We assumed that the current strength within two helical strands has a harmonic dependence on the coordinate measured along the helical line. This means that the electric current strength in the first and second strands in a pair of helices for the current time can be written as

where

and

are the coordinates calculated along the first and second helical line;

is the amplitude of current standing waves;

is the wavenumber;

is the cyclic current frequency. We assume that the incident wave is quasimonochromatic, and the excitation time is long enough to excite the resonant mode of the helix. Formulas (10) are valid in the case of resonant excitation of the helix, in which the total length of the helix L is approximately equal to an integer number of half-waves of the electromagnetic field:

, where n is an integer.

In addition to theoretical calculations, it is necessary to simulate the forces acting between the strands in a double helix.

3. Simulation of Forces at the Edges and in the Center of a Double DNA-like Helix in the Field of a Microwave Electromagnetic Wave

Effective electric currents along DNA helices generate forces, exerted on the DNA strands, that can potentially be used to manipulate the molecule. As stated previously, the conductivity of a DNA molecule is highly dependent on its environmental conditions. Specifically, water coverage can increase the conductivity of the molecule. Furthermore, it is important to note that within a DNA molecule, both conduction current and polarization current can manifest. The mechanisms and specifics of DNA molecule conduction described in (Wohlgamuth et al., 2013; Eley & Spivey, 1961; Snart, 1973; Tran et al., 2000; Warman et al., 1996; Dewarrat, 2002; Fink & Schönenberger, 1999; Cai et al., 2000; Yoo et al., 2001; Porath et al., 2000; Kasumov et al., 2001; Legrand et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2002; Guo et al., 2008; Gomez-Navarro et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2024; Fink, 2000; Mallajosyula & Pati, 2010; Hodzic et al., 2007; Wang, 2008; Charra et al., 2013) are outside the scope of this paper. This study work represents a step towards investigating the possibility of producing forces in the DNA molecule under the influence of an external electromagnetic field. The wavelength of this field is far greater than the helix turn length and falls within the ultraviolet range. Meanwhile, the length of the entire helix can be close to half a wavelength, meeting the requirements for resonance interaction. The DNA molecule is a macromolecule characterized by a periodic arrangement of atoms, molecules, and other chemical structures. The activation of these molecules and atoms occurs at specific frequencies. Of particular significance are instances where these frequencies, which are resonant for individual molecules and atoms, align with the half-wave resonance of the entire helix section. The question that emerges is whether half-wave resonance can occur in a DNA molecule or its segment as a result of periodically positioned absorption centers.

The forces that arise between the strands of a double DNA-like helix in the field of an electromagnetic wave under half-wave resonance are explored in prior research (Semchenko et al., 2020; Semchenko et al., 2016; Semchenko et al., 2018). In contrast to the study conducted in (Semchenko et al., 2016), which focuses on a symmetric double helix with a second-order symmetry axis, references (Semchenko et al., 2020; Semchenko et al., 2018) examine a double DNA-like helix, where the strands are displaced relative to each other along their shared axis, similar to the arrangement observed in actual DNA molecules. In doing so, forces of different directions are studied, such as radial, polar, and axial, which can lead to a change in the shape of the helix and the rupture of its strands. The research conducted in (Semchenko & Mikhalka, 2020) looks at the simultaneous occurrence of tension and unwinding forces acting on a single helix in the field of an incident electromagnetic wave under half-wave resonance. Studies (Semchenko et al., 2019; Semchenko et al., 2023) investigate the forces acting between the strands of a double DNA-like helix at higher frequency resonance, when the wavelength of the electromagnetic field is roughly equivalent to the length of the helical turn. While previous studies (Dharmadhikari et al., 2014; D’Souza et al., 2011; Baccarelli et al., 2011; Semchenko et al., 2020; Semchenko et al., 2016; Semchenko et al., 2018; Semchenko & Mikhalka, 2020; Semchenko et al., 2019; Semchenko et al., 2023) have focused on examining the impacts on the central regions of the helix that are distant from its edges, this research also explores the forces that emerge between the strands located at the edges of a double DNA-like helix under half-wave resonance.

An actual DNA molecule has nanometer dimensions, such as for the helix radius and for the helix pitch (Jd, 1953). As demonstrated in (Semchenko et al., 2020), a crucial attribute of the DNA molecule that must be considered while examining its electromagnetic properties is the helix pitch angle . This angle refers to the inclination created by the tangent to the helix line and the plane that is orthogonal to the helix axis. The calculation of this angle is derived from the experimental data presented in (Jd, 1953). It is determined to be . In the course of the simulation, we investigate the properties of a metallic DNA-like helix as a highly efficient conductor within the microwave range, while ensuring the pitch angle remains constant. We believe that the findings of this study have the potential for qualitative application to an actual DNA molecule inside the UV range. This approach is justified for the reasons listed below. Firstly, electrodynamic similarity is a fundamental concept that enables the scaling of objects and structures, facilitating the prediction of their electromagnetic properties throughout distinct frequency ranges. Secondly, an actual DNA molecule exhibits various conductive characteristics, functioning as a dielectric, conductor, or semiconductor depending on external conditions. Therefore, the DNA-like helix model as an ideal conductor, which is used in this paper, can provide a foundation for subsequent, more comprehensive studies and comparison with experimental data. Thus, the electromagnetic properties of the double DNA-like helix will be simulated while maintaining the pitch angle , and simultaneously adjusting its geometric parameters and the wavelength of the electromagnetic field in proportion.

So, let us consider a double DNA-like helix with parameters proportional to the size of a real DNA molecule in the presence of an incident external microwave-range wave. Force modeling is performed using the Ansys HFSS 3D electromagnetic simulation software. We assume that the double helix possesses conductive properties and consider it as an ideal conductor. The pitch angle of the helix is equal to

. The helix radius is

and the radius of the conductor cross-section is

. In reality, DNA strands can contain hundreds of turns, but in this instance, we will consider a segment with twenty and a half turns. This helix has a length of

and satisfies the half-wave resonance condition for a wave with a frequency of

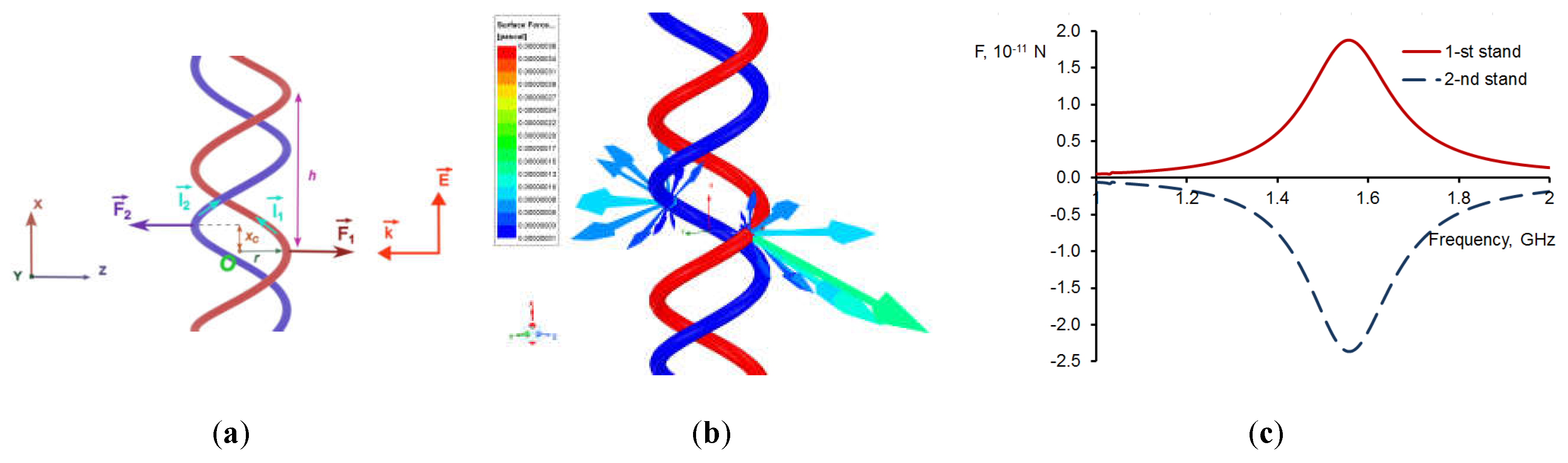

1.02 GHz. Suppose that the double helix is excited by a linearly polarized wave, wherein the electric field vector undergoes oscillations parallel to the helix axis and the wave vector is directed perpendicular to the helix axis, as depicted in

Figure 2(a). Similar to an actual DNA helix, the strands exhibit a mutual displacement along their common axis, denoted as

(Watson et al., 2013).

Figure 2(b) depicts the vector diagram of the forces operating on two strands of the DNA-like helix in its central region under half-wave resonance. Within this particular region of the double helix, the electric current strength in the two strands has the maximal value, with the currents in the two strands running in the same direction relative to the axis of the helix.

Figure 2 (c) illustrates the relationship between the Z-components of the forces, namely the radial components of the forces, and the wave frequency in the vicinity of resonance. As follows from the simulation results, the resonant frequency exhibits a minor shift towards the higher frequency region in comparison to the theoretically calculated value of

1.02 GHz.

Figure 2 (b) and

Figure 2 (c) illustrate the mutual radial repulsion between the two strands. The forces exerted within the double helix, which warrant particular attention, are illustrated in this depiction. Here, an essential characteristic of the forces acting within the double helix is evident, requiring further consideration. It follows from the laws of classical electrodynamics that when passing through parallel conductors, electric currents with the same direction are mutually attracted. If currents flow not through straightened but helical conductors, the interaction force of these currents is found to be highly dependent on the pitch angle of strands in the double helix. As demonstrated in (Semchenko et al., 2020), there exists a critical pitch angle of the double helix α0≈38 deg at which the radial force of interaction between the currents in the two strands turns to zero and undergoes a change in direction. For the DNA-like helix, characterized by a pitch angle of α=28.4 deg, the currents in the two strands do not attract, as in the case with straightened conductors. Instead, they exert a mutual repulsive force when they flow in the same direction with respect to the helical axis. Under half-wave resonance, exactly this eigenmode of current oscillations is excited in a double DNA-like helix.

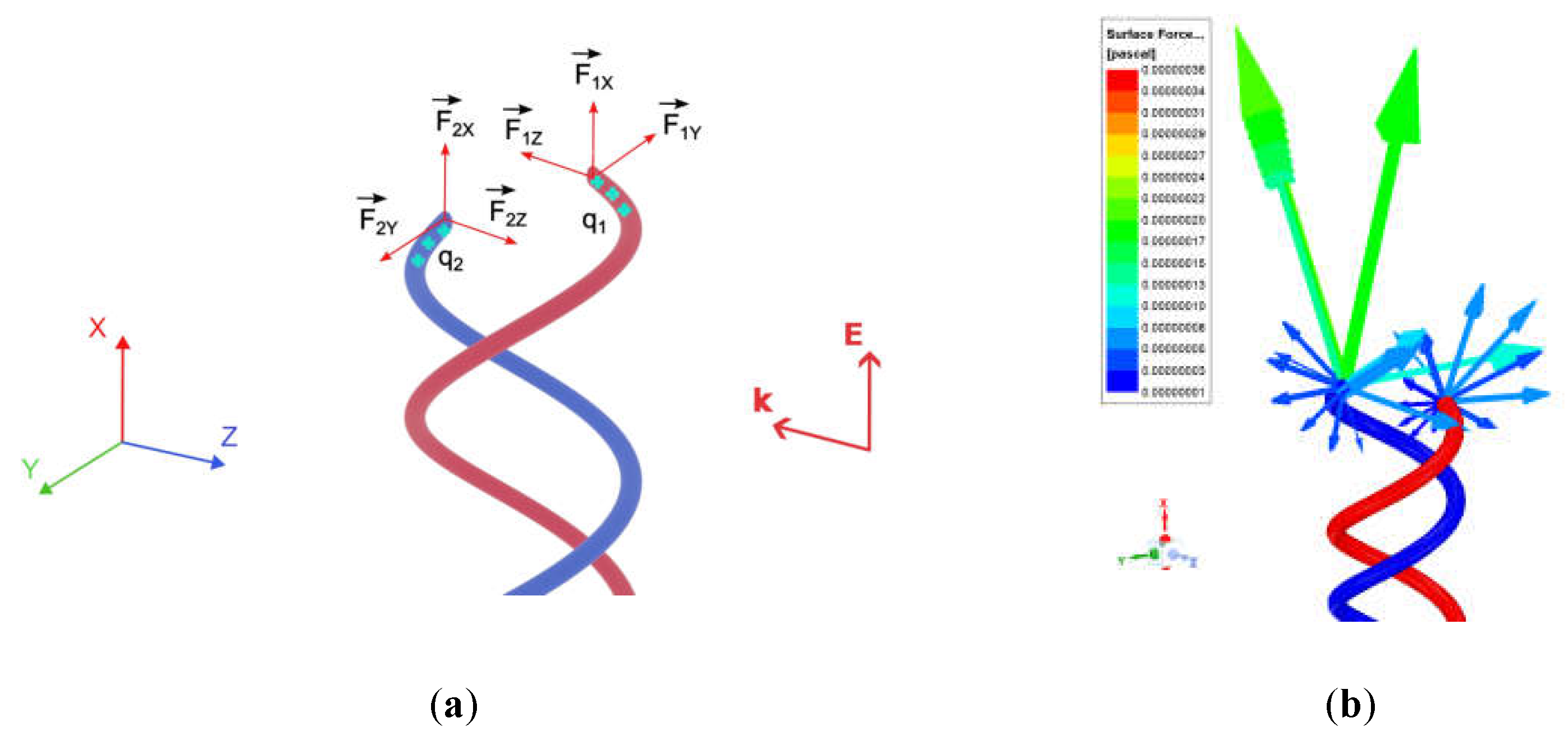

Figure 3(a) and

Figure 3(b) depict the forces exerted at the top edge of a double DNA-like helix when subjected to an incident linearly polarized wave at half-wave resonance. Additionally, a vector diagram illustrating these forces is shown. Upon activation of the specified mode of natural current oscillations, the electric charge density in the region under consideration, at the edges of the helix, reaches its maximal value. Furthermore, the charges present in the two strands exhibit identical signs.

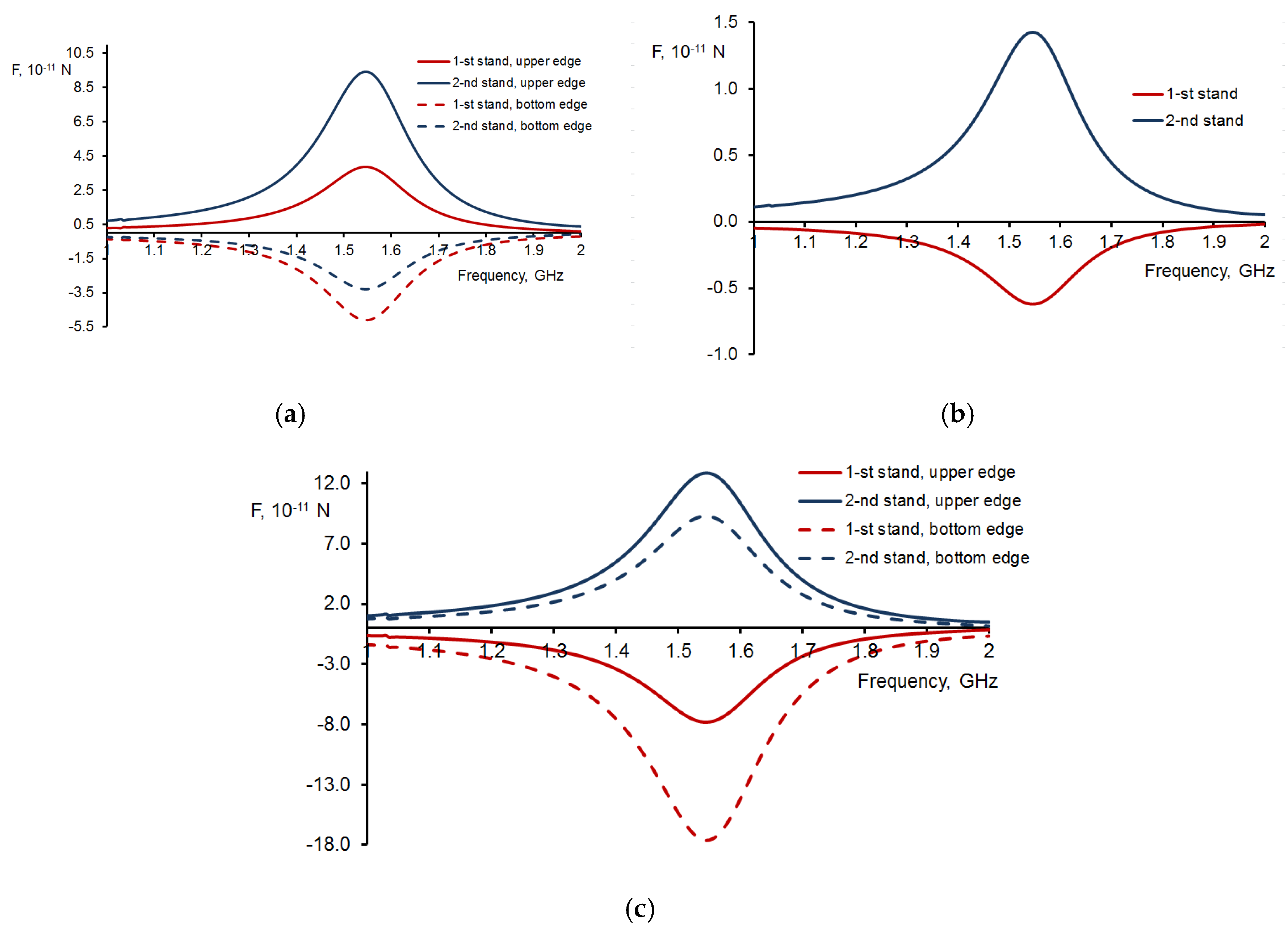

Figure 4 illustrates the frequency-dependent characteristics of the forces exerted on the edges of the helix in close proximity to the resonance frequency.

Figure 4(a) demonstrates that for both strands the inequalities

,

are satisfied for the X-components of the forces at the top and bottom edges of the double helix. Thus, the X-components of the forces acting at the top and bottom edges of the double DNA-like helix stretch both strands of the helix.

Figure 4(b) illustrates that the Y-components of the forces exerted on the top edge of the double DNA-like helix result in a mutual repulsion between the helix strands. Similar forces of mutual repulsion between two strands exist at the bottom edge of the double helix. The indicated direction of the X- and Y-components of the forces is due to the fact that charges of the same sign are induced on the two strands in the regions located symmetrically relative to the helix axis. With the help of

Figure 4 (c), it is possible to analyze the direction of the torque moment

operating on the strands of the double helix at its edges. The inequalities

,

are satisfied for the X-components of the torque moment at the top and bottom edges of the double helix, as shown in

Figure 4(c). This paper examines a right-handed double helix that is analogous to an actual DNA molecule. In this regard,

Figure 4 (c) shows that the Z-components of the forces acting on the top and bottom edges of the right-handed double DNA-like helix induce an additional twisting effect on the helix.

4. Conclusion

This article is interdisciplinary and focuses primarily on double DNA-like helices, which can be used as elements of metamaterials, provided they are scaled to the required frequency range of electromagnetic waves. In addition, the results obtained can be applied to real DNA while studying the disruptive effects of electromagnetic waves. The study considers the activation of the intrinsic mode of oscillations of electric current and electric charges in a double DNA-like helix, which correspond to a half-wave resonance, under the influence of an incident electromagnetic wave. Interaction forces manifest between the strands comprising the double helix, with primarily electric currents interacting in the central region and predominantly electric charges interacting at the edges. The simulation demonstrates that the direction of these interaction forces depends strongly on the pitch angle of the helix. For a double DNA-like helix with a pitch angle of α=28.4 degree, not only charges but also currents repel in the two strands of the helix, i.e., there is radial repulsion of the strands in all their regions. In addition, the edges of the helix are affected by the simultaneous tension and torsion forces of the helical strands. Hence, when subjected to an electromagnetic wave under the half-wave resonance condition, the double helix is susceptible to damage in all its areas. Conversely, the impact of electromagnetic waves may provide a novel potential for controlling the shape of the double helix. These nonlinear effects must be taken into account for actual DNA molecules in which the strands are very close to each other and the equilibrium of these molecules is dependent on the interaction of currents and charges in the strands. When developing metamaterials and metasurfaces with double DNA-like helical elements, the interaction of helical conductors must also be considered (Lagarkov et al., 1997; Semchenko et al., 2014; Semchenko et al., 2017; Gansel et al., 2009; Slobozhanyuk et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2012; Kaschke & Wegener, 2015; Esposito et al., 2015; Schäferling et al., 2014).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S.M. and I.V.S.; methodology, I.V.S, A.L.S. and I.S.M.; investigation, A.L.S., I.S.M., S.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.L., I.V.S. and S.A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.V.L., I.V.S. and S.A.K.; visualization, I.S.M.; supervision, A.V.L., I.V.S. and S.A.K.; project administration, A.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was conducted as part of the State Research Program titled "Photonics and Electronics for Innovations."

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Tatyana Lozovskaya, a senior teacher, for their help in translating the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Semchenko, I. V., Mikhalka, I. S., Khakhomov, S. A., Samofalov, A. L., Balmakou, A. P. DNA-like Helices as Nanosized Polarizers of Electromagnetic Waves. Frontiers in Nanotechnology 2022, 4, 794213.

- Semchenko, I. V., Khakhomov, S. A. Application of DNA molecules in nature-inspired technologies: a mini review. Frontiers in Nanotechnology 2023, 5, 1185429.

- Ploeser, J. M., Loring, H. S. The ultraviolet absorption spectra of the pyrimidine ribonucleosides and ribonucleotides. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1949, 178(1), 431–437. [CrossRef]

- Voet, D., Gratzer, W. B., Cox, R. A., Doty, P. Absorption spectra of nucleotides, polynucleotides, and nucleic acids in the far ultraviolet. Biopolymers: Original Research on Biomolecules 1963, 1(3), 193-208.

- Konev, S., Volotovsky, I., Photobiology. BSU: Minsk, Belarus, 1979, 385 p. (in Russian).

- Watson, J.D. Crick, F.H.C. A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid, Nature 1953, 171, p. 737–738.

- Watson, J.D. Baker, T.A. Bell, S.P. Gann, A. Levine, M. Losick, R. Molecular Biology of the Gene, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2013, 912 p.

- Wohlgamuth, C. H., McWilliams, M. A., Slinker, J. D. DNA as a molecular wire: Distance and sequence dependence. Analytical chemistry 2013, 85(18), 8634-8640.

- Eley, D. D., Spivey, D. I. Semiconductivity of organic substances. Part 7.—The polyamides. Transactions of the Faraday Society 1961, 57, 2280-2287.

- Snart, R. S. The electrical properties and stability of DNA to UV radiation and aromatic hydrocarbons. Biopolymers: Original Research on Biomolecules 1973, 12(7), 1493-1503.

- Tran, P., Alavi, B., Gruner, G. Charge transport along the λ-DNA double helix. Physical Review Letters 2000, 85(7), 1564.

- Warman, J. M., de Haas, M. P., Rupprecht, A. DNA: a molecular wire?. Chemical physics letters 1996, 249(5-6), 319-322.

- Dewarrat, F. Electric Characterization of DNA; Publisher: Basel University, Basel, Switzerland, 2002; 96 p.

- Fink, H. W., Schönenberger, C. Electrical conduction through DNA molecules. Nature 1999, 398(6726), 407–410. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L., Tabata, H., Kawai, T. Self-assembled DNA networks and their electrical conductivity. Applied Physics Letters 2000, 77(19), 3105–3106. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K. H., Ha, D. H., Lee, J. O., Park, J. W., Kim, J., Kim, J. J., Choi, H. Y. Electrical conduction through poly (dA)-poly (dT) and poly (dG)-poly (dC) DNA molecules. Physical review letters 2001, 87(19), 198102.

- Porath, D., Bezryadin, A., De Vries, S., Dekker, C. Direct measurement of electrical transport through DNA molecules. Nature 2000, 403(6770), 635–638. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasumov, A. Y., Kociak, M., Gueron, S., Reulet, B., Volkov, V. T., Klinov, D. V., Bouchiat, H. Proximity-induced superconductivity in DNA. Science 2001, 291(5502), 280-282.

- Legrand, O., Côte, D., Bockelmann, U. Single molecule study of DNA conductivity in aqueous environment. Physical Review E—Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics 2006, 73(3), 031925.

- Zhang, Y., Austin, R. H., Kraeft, J., Cox, E. C., Ong, N. P. Insulating behavior of λ-DNA on the micron scale. Physical Review Letters 2002, 89(19), 198102.

- Guo, X., Gorodetsky, A. A., Hone, J., Barton, J. K., Nuckolls, C. Conductivity of a single DNA duplex bridging a carbon nanotube gap. Nature nanotechnology 2008, 3(3), 163-167.

- Gomez-Navarro, C., Moreno-Herrero, F., De Pablo, P. J., Colchero, J., Gomez-Herrero, J., Baro, A. M. Contactless experiments on individual DNA molecules show no evidence for molecular wire behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99(13), 8484-8487.

- Hu, B. N., Gao, C., Dong, H. L. A brief analysis of the conductivity of DNA. Acta Polymerica Sinica 2024, 55(2), 129–141.

- Fink, H. W. Electrical conduction through DNA molecules. Electronic Properties of Novel MATERIALS-MOLECULAR Nanostructures: XIV International Winterschool/EuroConference 2000, 544, 457–461. [Google Scholar]

- Mallajosyula, S. S., Pati, S. K. Toward DNA conductivity: a theoretical perspective. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2010, 1(12), 1881-1894.

- Hodzic, V., Hodzic, V., Newcomb, R. W. Modeling of the electrical conductivity of DNA. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2007, 54(11), 2360-2364.

- Wang, J. Electrical conductivity of double stranded DNA measured with ac impedance spectroscopy. Physical Review B—Condensed Matter and Materials Physics 2008, 78(24), 245304.

- Charra, F., Agranovich, V.M., Kajzar, F. Organic Nanophotonics; Springer Science Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2003, 193–206.

- Travers, A., Muskhelishvili, G. DNA supercoiling—a global transcriptional regulator for enterobacterial growth? Nature Reviews Microbiology 2005, 3(2), 157–169. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmadhikari, A. K., Bharambe, H., Dharmadhikari, J. A., D’Souza, J. S., Mathur, D. DNA damage by OH radicals produced using intense, ultrashort, long wavelength laser pulses. Physical review letters 2014, 112(13), 138105.

- D’Souza, J. S., Dharmadhikari, J. A., Dharmadhikari, A. K., Rao, B. J., Mathur, D. Effect of intense, ultrashort laser pulses on DNA plasmids in their native state: strand breakages induced by in situ electrons and radicals. Physical Review Letters 2011, 106(11), 118101.

- Baccarelli, I., Bald, I., Gianturco, F. A., Illenberger, E., Kopyra, J. Electron-induced damage of DNA and its components: Experiments and theoretical models. Physics Reports 2011, 508(1-2), 1-44.

- Semchenko, I. V., Mikhalka, I. S., Faniayeu, I. A., Khakhomov, S. A., Balmakou, A. P., Tretyakov, S. A. Optical forces acting on a double dna-like helix, its unwinding and strands rupture. In Photonics 2020, 7( 4), p. 83).

- Semchenko, I. V., Khakhomov, S. A., Samofalov, A. L., Songsong, Q. The equilibrium state of bifilar helix as element of metamaterials. In JJAP Conference Proceedings 14th International Conference on Global Research and Education, Inter-Academia 2015 (pp. 011112-011112). The Japan Society of Applied Physics 2016.

- Semchenko, I., Khakhomov, S., Balmakou, A., Mikhalka, I. Interaction forces of electric currents and charges in a double DNA-like helix and its equilibrium. In 2018 12th International Congress on Artificial Materials for Novel Wave Phenomena (Metamaterials), 2018, pp. 281-283. IEEE.

- Semchenko, I.V. Mikhalka, I.S. Simultaneous stretching and unwinding of helical elements of metamaterials under the influence of an electromagnetic wave. 14th International Congress on Artificial Materials for Novel Wave Phenomena – Metamaterials 2020, New York, USA, Sept. 28th – Oct. 3rd, 2020, X-121 - X-123.

- Semchenko, I. V., Mikhalka, I. S., Khakhomov, S. A., Balmakou, A. P. The interaction of strands in a double DNA-like helix at high-frequency resonance. In 13th International Congress on Artificial Materials for Novel Wave Phenomena Metamaterials 2019, pp. 16-21.

- Semchenko, I. V., Khakhomov, S. A., Mikhalka, I. S., Samofalov, A. L., Somov, P. V. Polarization Selectivity of a Double DNA-Like Helix as an Element of Metamaterials and Metasurfaces. Journal of Applied Spectroscopy 2023, 90(2), 419-426.

- Lagarkov, A. N., Semenenko, V. N., Chistyaev, V. A., Ryabov, D. E., Tretyakov, S. A., Simovski, C. R. Resonance properties of bi-helix media at microwaves. Electromagnetics 1997, 17(3), 213-237.

- Semchenko, I. V., Khakhomov, S. A., Asadchy, V. S., Naumova, E. V., Prinz, V. Y., Golod, S. V., Sinitsyn, G. V. Investigation of the properties of weakly reflective metamaterials with compensated chirality. Crystallography Reports 2014, 59, 480–485.

- Semchenko, I. V., Khakhomov, S. A., Asadchy, V. S., Golod, S. V., Naumova, E. V., Prinz, V. Y., Malevich, V. L. Investigation of electromagnetic properties of a high absorptive, weakly reflective metamaterial—Substrate system with compensated chirality. Journal of Applied Physics 2017, 121(1), 015108-1- 015108-8.

- Gansel, J. K., Thiel, M., Rill, M. S., Decker, M., Bade, K., Saile, V., Wegener, M. Gold helix photonic metamaterial as broadband circular polarizer. Science 2009, 325(5947), 1513–1515. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slobozhanyuk, A. P., Lapine, M., Powell, D. A., Shadrivov, I. V., Kivshar, Y. S., McPhedran, R. C., Belov, P. A. Flexible helices for nonlinear metamaterials. Adv. Mater 2013, 25(25), 3409–3412.

- Zhao, Z., Gao, D., Bao, C., Zhou, X., Lu, T., Chen, L. High extinction ratio circular polarizer with conical double-helical metamaterials. Journal of lightwave technology 2012, 30(15), 2442-2446.

- Kaschke, J., Wegener, M. Gold triple-helix mid-infrared metamaterial by STED-inspired laser lithography. Optics letters 2015, 40(17), 3986-3989.

- Esposito, M., Tasco, V., Todisco, F., Cuscunà, M., Benedetti, A., Sanvitto, D., Passaseo, A. Triple-helical nanowires by tomographic rotatory growth for chiral photonics. Nature communications 2015, 6(1), 6484.

- Schäferling, M., Yin, X., Engheta, N., Giessen, H. Helical plasmonic nanostructures as prototypical chiral near-field sources. Acs Photonics 2014, 1(6), 530-537.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).