Submitted:

19 July 2024

Posted:

22 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

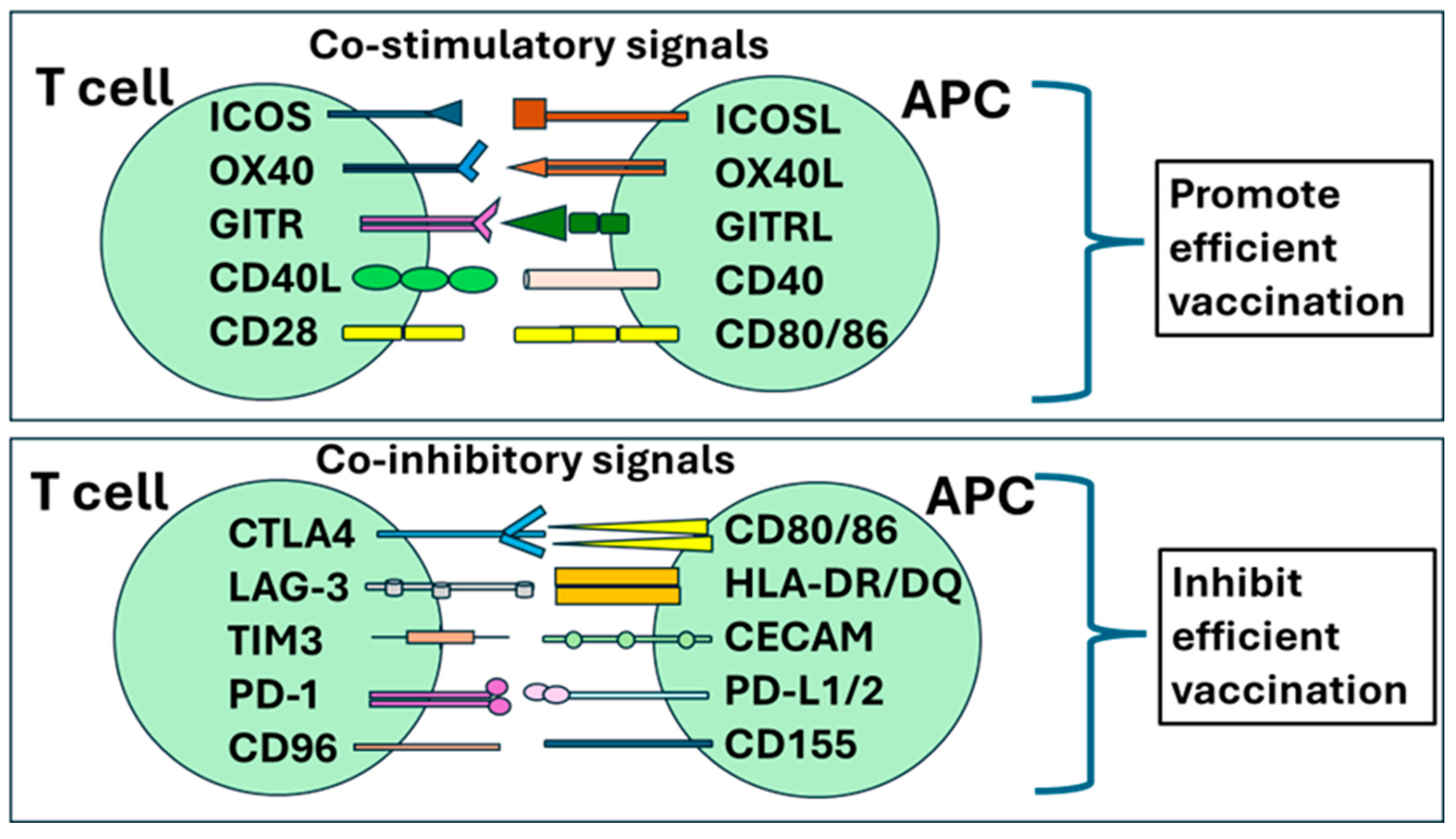

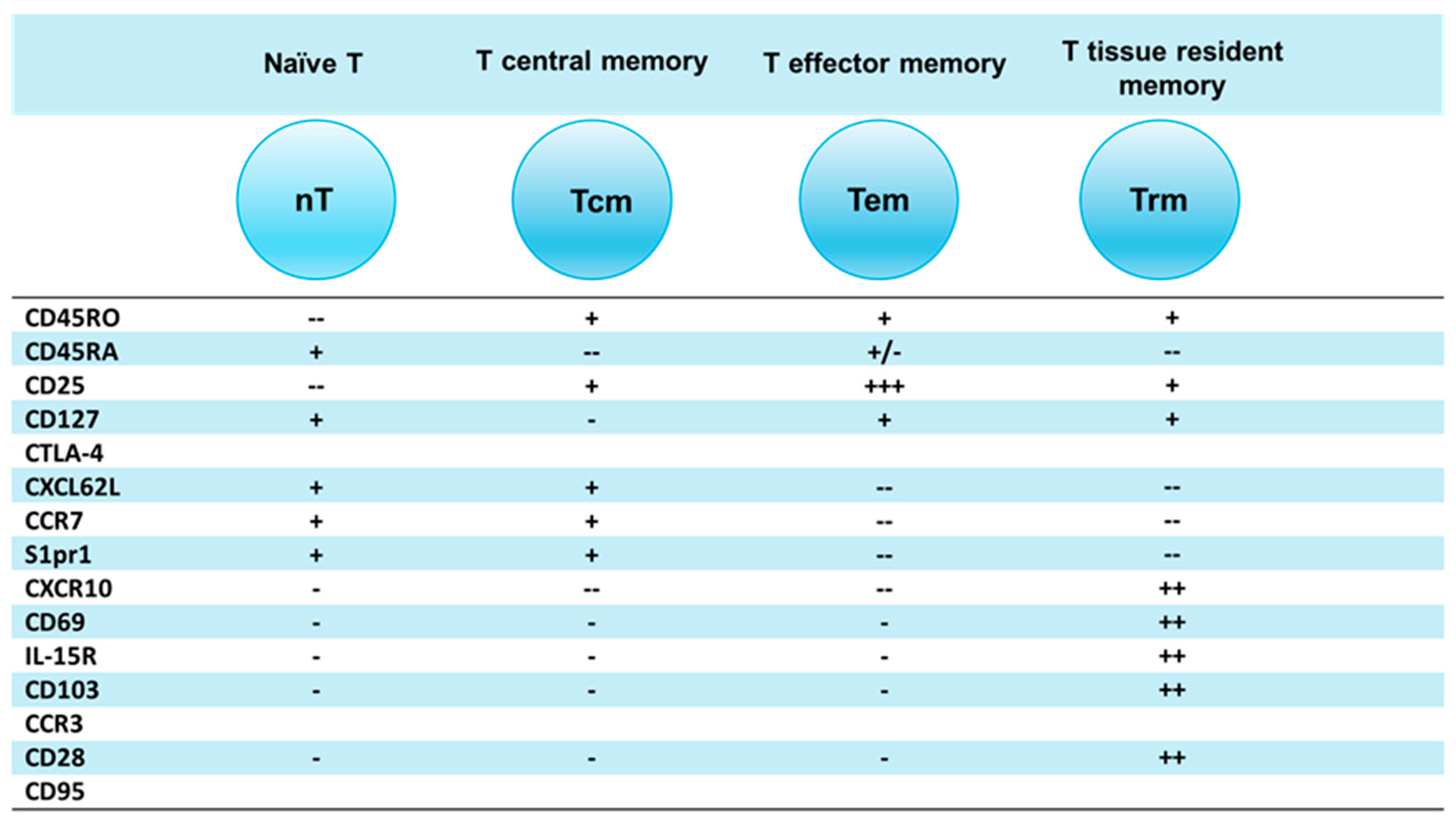

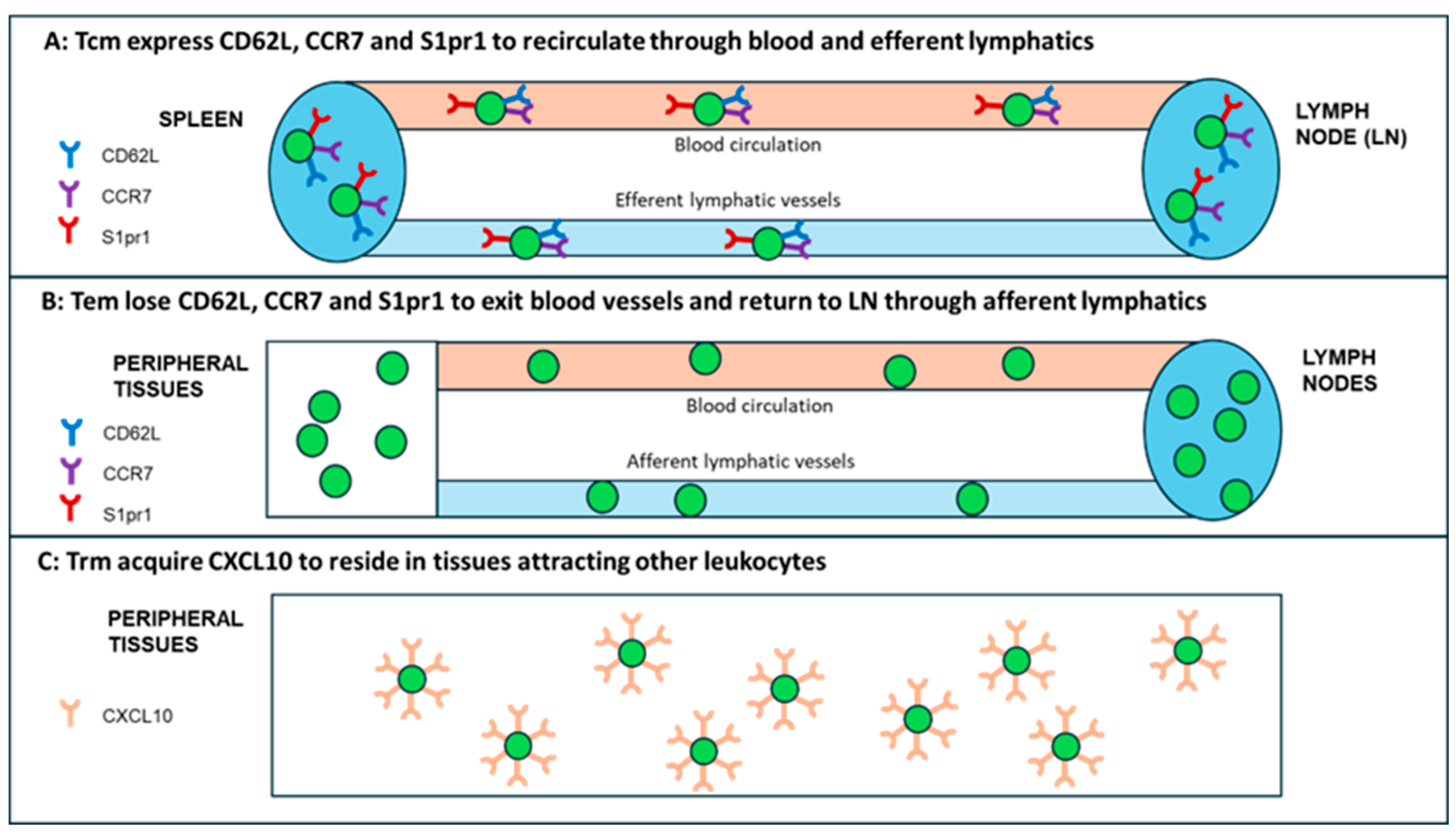

2. Description of Memory T Cell Immune Responses during Vaccination

3. The Role of Treg Cells in Immune Response to Vaccines

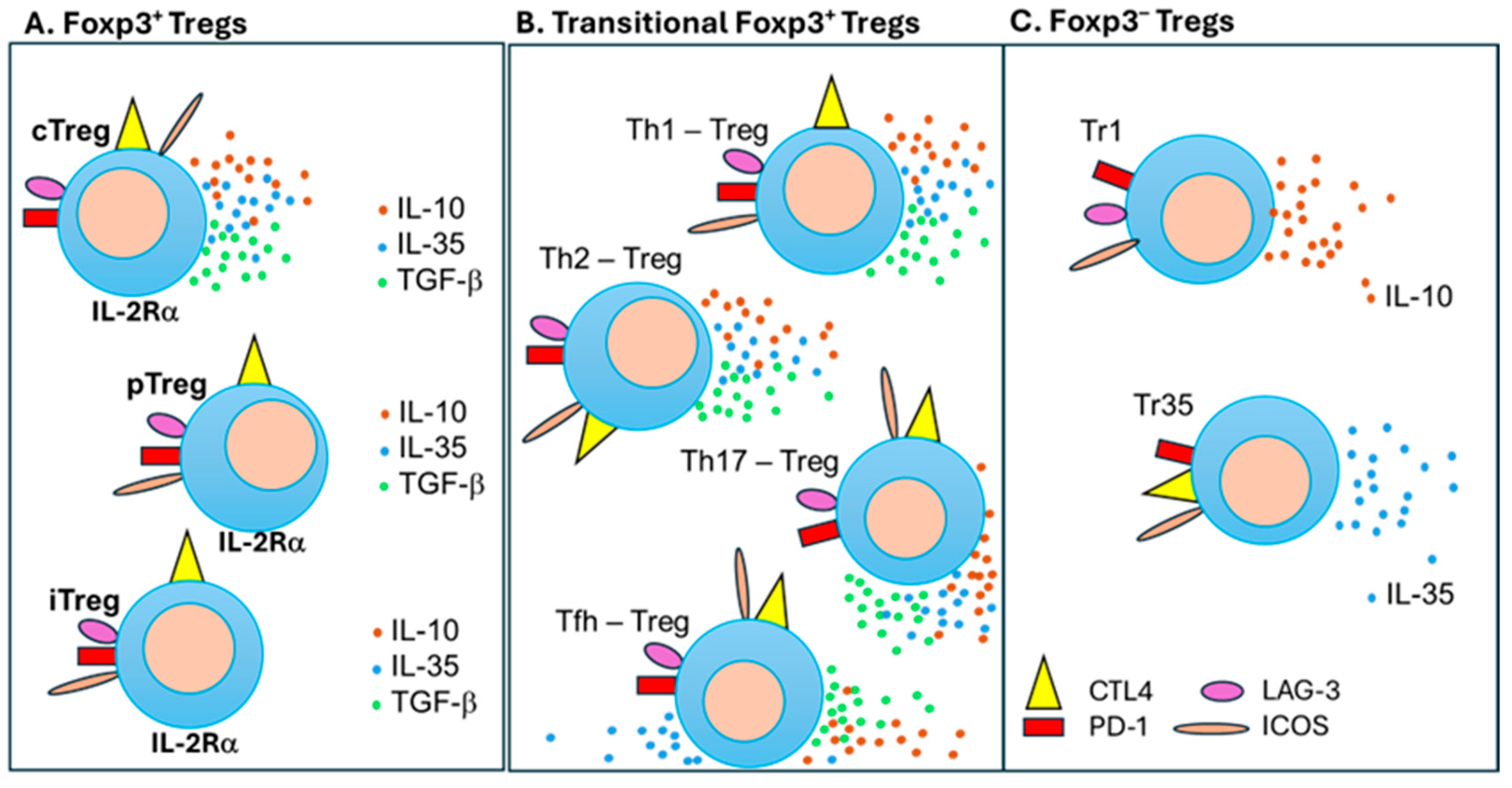

3.1. General Description of T Regulatory Cells

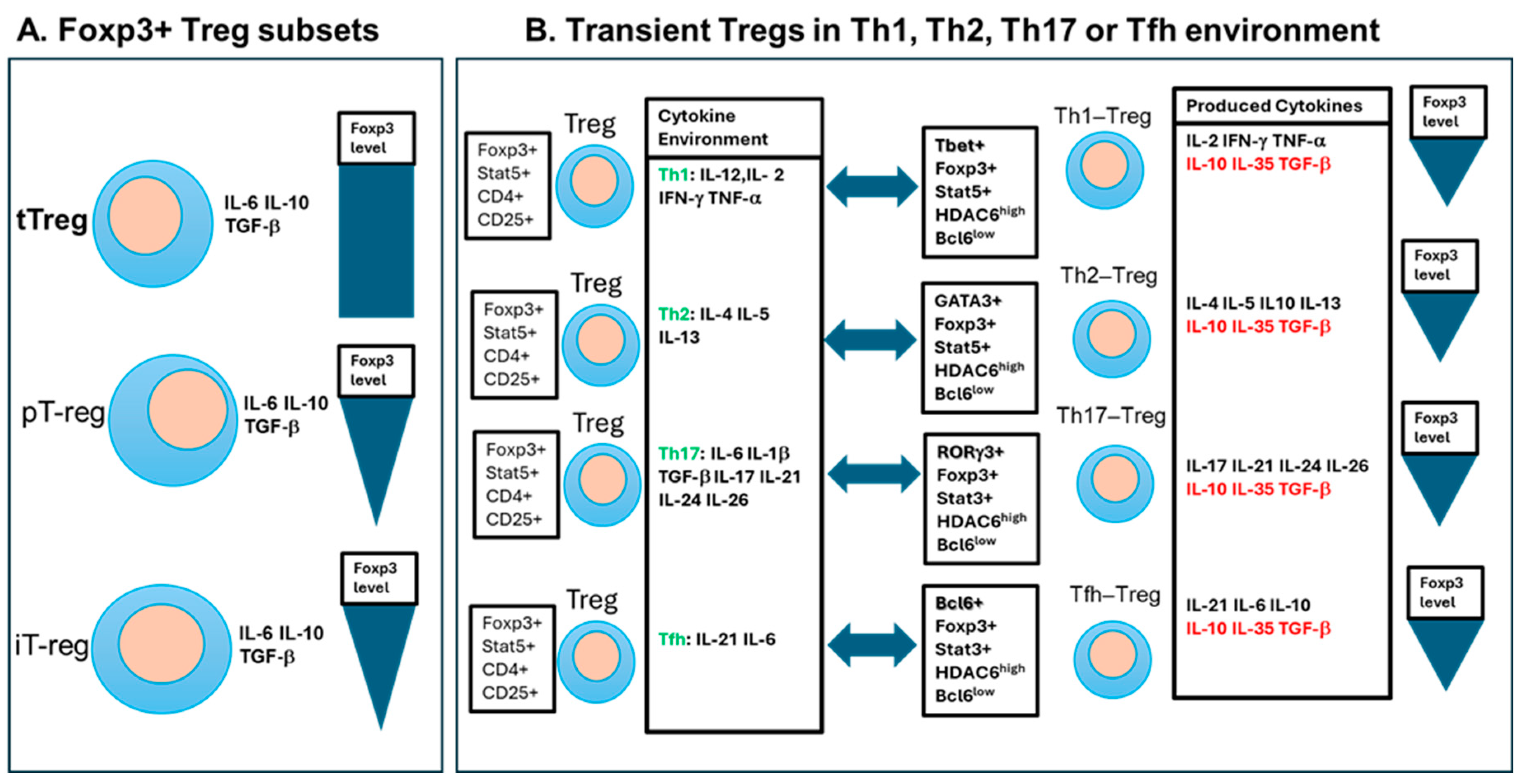

3.2. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg Cells

3.3. Transient Functional Treg Cell Subsets

3.4. Tr1 and Tr35 Cells

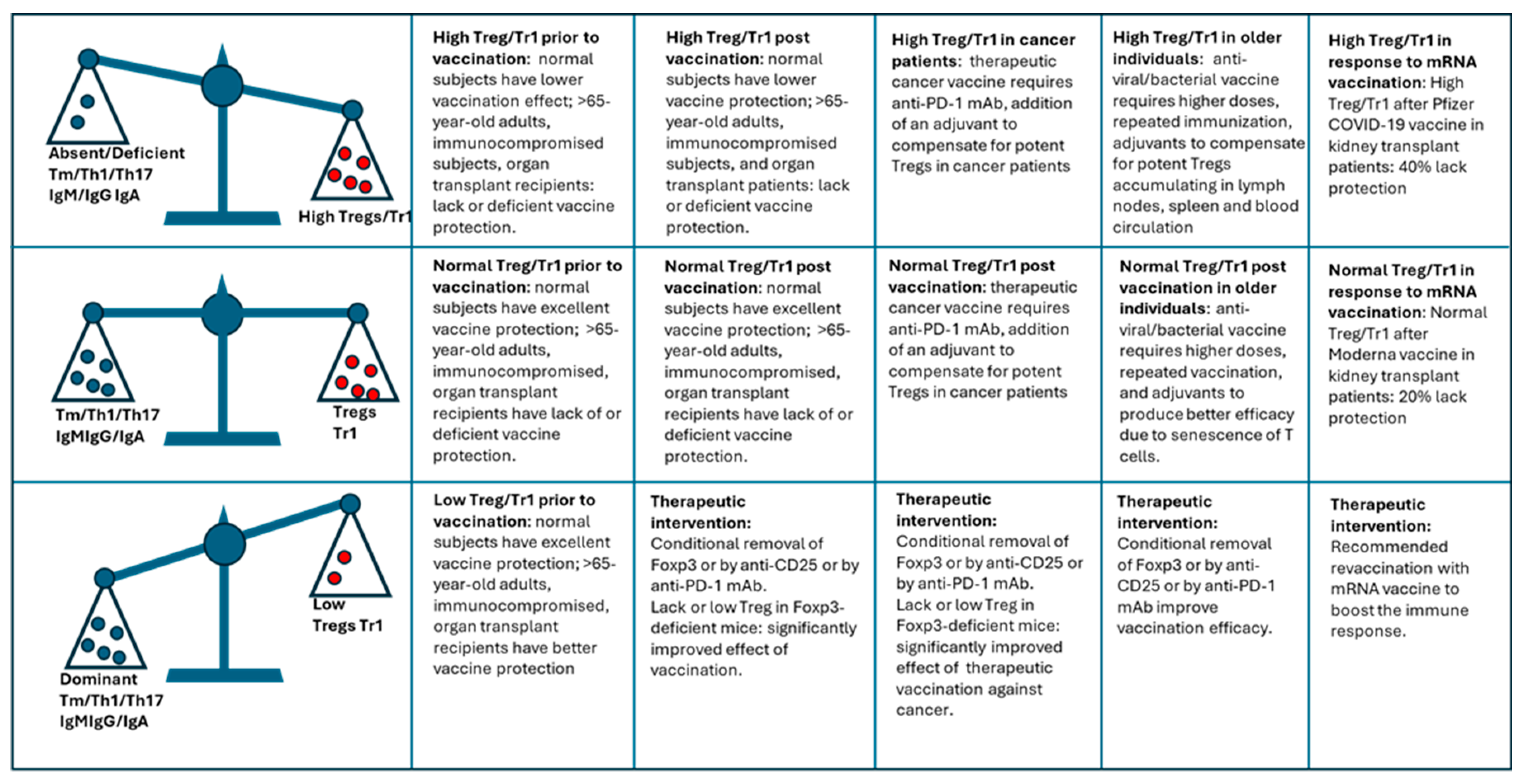

4. Regulatory T Cells Down-Regulate the Immune Response to Vaccines

4.1. Pre-Vaccination Treg Levels Affects Vaccination Efficacy

4.2. Presence of Tregs Affects Efficacy after Vaccines against Infectious Diseases

4.3. Presence of Tregs Affects Efficacy after Vaccines against Cancer

4.2. Depletion of Treg Cells Improves Vaccination Efficacy

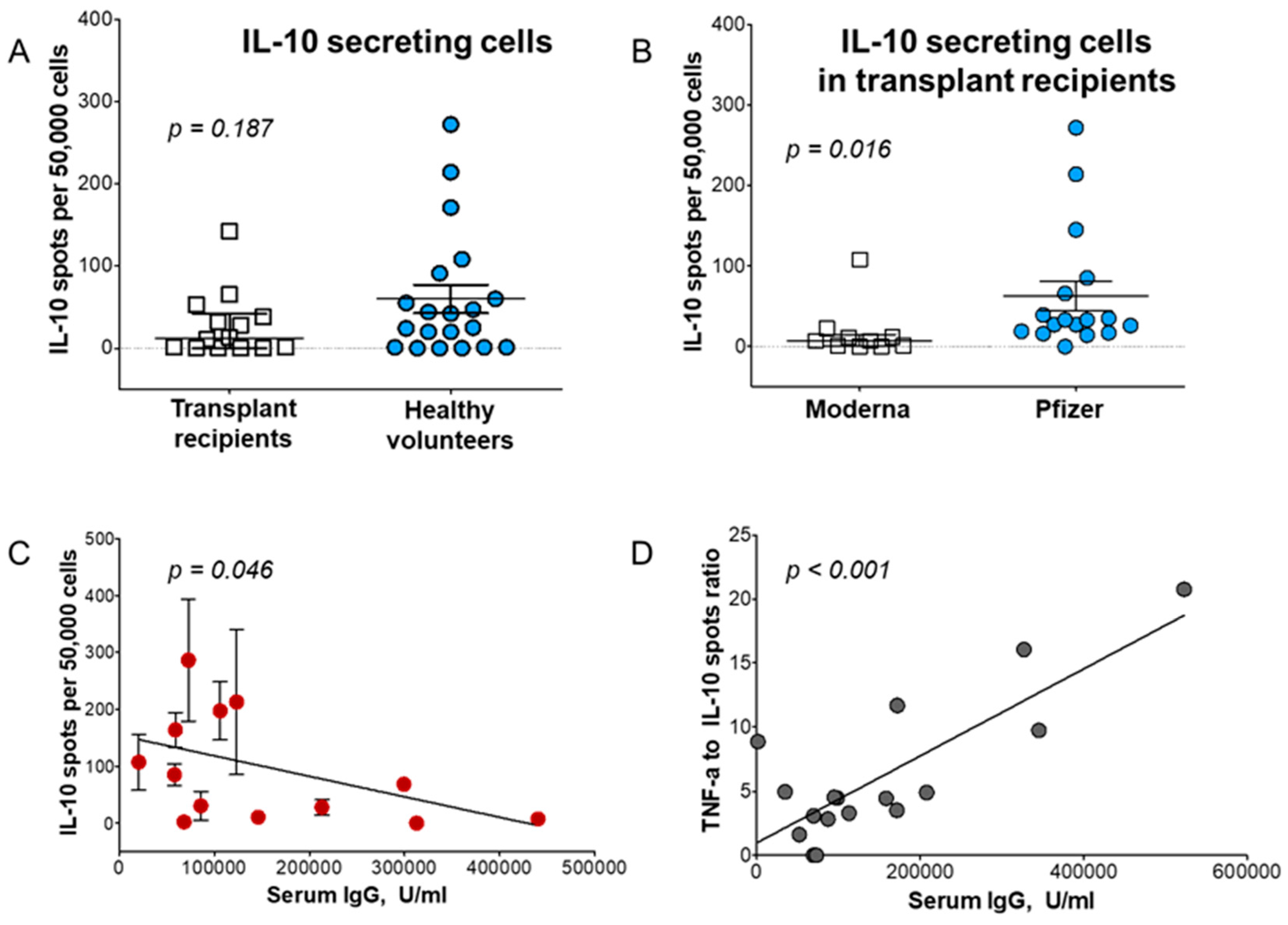

5. The Role of Tr1 Cells in Vaccination of Transplant Recipients

6. Methods to Improve Vaccination Efficacy

6.1. Higher Doses and Repeated Vaccination

6.2. Alternative Administration Routes

6.3. Novel Adjuvants

6.4. Treg Modulation to Improve Vaccine Immunogenicity

6.5. Immunomodulatory Agents

6.6. Senolytics Drug Therapy in Older People

7. Summary

Funding

References

- Baxby D. Jenner and the control of smallpox. Trans Med Soc Lond. 1996;113:18-22. PubMed PMID: 10326082.

- Barquet N, Domingo P. Smallpox: the triumph over the most terrible of the ministers of death. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(8 Pt 1):635-42. PubMed PMID: 9341063. [CrossRef]

- Organization WH. Polio vaccines: WHO position paper - June 2022. Weekly epidemiological record. 2022;97(25):277-300.

- Organization WH. Measles vaccines: WHO position paper - April 2017. Weekly epidemiological record. 2017;92(17):205-28.

- Pleguezuelos O, James E, Fernandez A, Lopes V, Rosas LA, Cervantes-Medina A, Cleath J, Edwards K, Neitzey D, Gu W, Hunsberger S, Taubenberger JK, Stoloff G, Memoli MJ. Efficacy of FLU-v, a broad-spectrum influenza vaccine, in a randomized phase IIb human influenza challenge study. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5(1):22. Epub 20200313. PubMed PMID: 32194999; PMCID: PMC7069936. [CrossRef]

- Atsmon J, Kate-Ilovitz E, Shaikevich D, Singer Y, Volokhov I, Haim KY, Ben-Yedidia T. Safety and immunogenicity of multimeric-001--a novel universal influenza vaccine. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(3):595-603. Epub 20120209. PubMed PMID: 22318394. [CrossRef]

- Hu C, Bai Y, Liu J, Wang Y, He Q, Zhang X, Cheng F, Xu M, Mao Q, Liang Z. Research progress on the quality control of mRNA vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2024;23(1):570-83. Epub 20240524. PubMed PMID: 38733272. [CrossRef]

- Pollard AJ, Bijker EM. A guide to vaccinology: from basic principles to new developments. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(2):83-100. Epub 20201222. PubMed PMID: 33353987; PMCID: PMC7754704. [CrossRef]

- Lagana A, Visalli G, Di Pietro A, Facciola A. Vaccinomics and adversomics: key elements for a personalized vaccinology. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2024;13(2):105-20. Epub 20240430. PubMed PMID: 38752004; PMCID: PMC11091437. [CrossRef]

- Clinic M. Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic 2024 [updated March 13, 2024June 17, 2024]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/infectious-diseases/in-depth/vaccine-guidance/art-20536857.

- Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Factors That Influence the Immune Response to Vaccination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32(2). Epub 20190313. PubMed PMID: 30867162; PMCID: PMC6431125. [CrossRef]

- Geckin B, Konstantin Fohse F, Dominguez-Andres J, Netea MG. Trained immunity: implications for vaccination. Curr Opin Immunol. 2022;77:102190. Epub 20220518. PubMed PMID: 35597182. [CrossRef]

- Danziger-Isakov L, Kumar D, Practice AICo. Vaccination of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients: Guidelines from the American society of transplantation infectious diseases community of practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33(9):e13563. Epub 20190605. PubMed PMID: 31002409. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Zapien GJ, Martinez-Cuazitl A, Sanchez-Brito M, Delgado-Macuil RJ, Atriano-Colorado C, Garibay-Gonzalez F, Sanchez-Monroy V, Lopez-Reyes A, Mata-Miranda MM. Comparison of the Immune Response in Vaccinated People Positive and Negative to SARS-CoV-2 Employing FTIR Spectroscopy. Cells. 2022;11(23). Epub 20221201. PubMed PMID: 36497139; PMCID: PMC9740721. [CrossRef]

- Lindenstrom T, Woodworth J, Dietrich J, Aagaard C, Andersen P, Agger EM. Vaccine-induced th17 cells are maintained long-term postvaccination as a distinct and phenotypically stable memory subset. Infect Immun. 2012;80(10):3533-44. Epub 20120730. PubMed PMID: 22851756; PMCID: PMC3457559. [CrossRef]

- Roncarolo MG, Gregori S, Battaglia M, Bacchetta R, Fleischhauer K, Levings MK. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:28-50. PubMed PMID: 16903904. [CrossRef]

- Schenkel JM, Masopust D. Tissue-resident memory T cells. Immunity. 2014;41(6):886-97. Epub 20141206. PubMed PMID: 25526304; PMCID: PMC4276131. [CrossRef]

- von Andrian UH, Mempel TR. Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(11):867-78. PubMed PMID: 14668803. [CrossRef]

- Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Pillars article: two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999. 401: 708-712. J Immunol. 2014;192(3):840-4. PubMed PMID: 24443506.

- Yenyuwadee S, Sanchez-Trincado Lopez JL, Shah R, Rosato PC, Boussiotis VA. The evolving role of tissue-resident memory T cells in infections and cancer. Sci Adv. 2022;8(33):eabo5871. Epub 20220817. PubMed PMID: 35977028; PMCID: PMC9385156. [CrossRef]

- von Andrian UH, Mackay CR. T-cell function and migration. Two sides of the same coin. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(14):1020-34. PubMed PMID: 11018170. [CrossRef]

- Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 2010;33(4):451-63. PubMed PMID: 21029957; PMCID: PMC3760154. [CrossRef]

- Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272(5258):60-6. PubMed PMID: 8600538. [CrossRef]

- Mackay CR, Marston WL, Dudler L. Naive and memory T cells show distinct pathways of lymphocyte recirculation. J Exp Med. 1990;171(3):801-17. PubMed PMID: 2307933; PMCID: PMC2187792. [CrossRef]

- Karin N, Razon H. Chemokines beyond chemo-attraction: CXCL10 and its significant role in cancer and autoimmunity. Cytokine. 2018;109:24-8. Epub 20180212. PubMed PMID: 29449068. [CrossRef]

- Gershon RK, Kondo K. Cell interactions in the induction of tolerance: the role of thymic lymphocytes. Immunology. 1970;18(5):723-37. PubMed PMID: 4911896; PMCID: PMC1455602.

- Stepkowski SM, Bitter-Suermann H, Duncan WR. Induction of transplantation tolerance in rats by spleen allografts. II. Evidence that W3/25+ T suppressor/inducer and OX8+ T suppressor/effector cells are required to mediate specific unresponsiveness. Transplantation. 1987;44(3):443-8. PubMed PMID: 2957840. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155(3):1151-64. PubMed PMID: 7636184.

- Baecher-Allan C, Brown JA, Freeman GJ, Hafler DA. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol. 2001;167(3):1245-53. PubMed PMID: 11466340. [CrossRef]

- Taams LS, Smith J, Rustin MH, Salmon M, Poulter LW, Akbar AN. Human anergic/suppressive CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells: a highly differentiated and apoptosis-prone population. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(4):1122-31. PubMed PMID: 11298337. [CrossRef]

- Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Stassen M, Tuettenberg A, Knop J, Enk AH. Identification and functional characterization of human CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties isolated from peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 2001;193(11):1285-94. PubMed PMID: 11390435; PMCID: PMC2193380. [CrossRef]

- Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Pillars Article: Control of Regulatory T Cell Development by the Transcription Factor Foxp3. Science 2003. 299: 1057-1061. J Immunol. 2017;198(3):981-5. PubMed PMID: 28115586.

- Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Pillars Article: Foxp3 Programs the Development and Function of CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003. 4: 330-336. J Immunol. 2017;198(3):986-92. PubMed PMID: 28115587.

- Luo Y, Xue Y, Wang J, Dang J, Fang Q, Huang G, Olsen N, Zheng SG. Negligible Effect of Sodium Chloride on the Development and Function of TGF-beta-Induced CD4(+) Foxp3(+) Regulatory T Cells. Cell Rep. 2019;26(7):1869-79 e3. PubMed PMID: 30759396; PMCID: PMC6948355. [CrossRef]

- Zheng SG, Wang J, Horwitz DA. Cutting edge: Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by IL-2 and TGF-beta are resistant to Th17 conversion by IL-6. J Immunol. 2008;180(11):7112-6. PubMed PMID: 18490709. [CrossRef]

- Halim L, Romano M, McGregor R, Correa I, Pavlidis P, Grageda N, Hoong SJ, Yuksel M, Jassem W, Hannen RF, Ong M, McKinney O, Hayee B, Karagiannis SN, Powell N, Lechler RI, Nova-Lamperti E, Lombardi G. An Atlas of Human Regulatory T Helper-like Cells Reveals Features of Th2-like Tregs that Support a Tumorigenic Environment. Cell Rep. 2017;20(3):757-70. PubMed PMID: 28723576; PMCID: PMC5529316. [CrossRef]

- Romagnani S, Maggi E, Liotta F, Cosmi L, Annunziato F. Properties and origin of human Th17 cells. Mol Immunol. 2009;47(1):3-7. Epub 20090203. PubMed PMID: 19193443. [CrossRef]

- Chung Y, Tanaka S, Chu F, Nurieva RI, Martinez GJ, Rawal S, Wang YH, Lim H, Reynolds JM, Zhou XH, Fan HM, Liu ZM, Neelapu SS, Dong C. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat Med. 2011;17(8):983-8. Epub 20110724. PubMed PMID: 21785430; PMCID: PMC3151340. [CrossRef]

- Suhrkamp I, Scheffold A, Heine G. T-cell subsets in allergy and tolerance induction. Eur J Immunol. 2023;53(10):e2249983. Epub 20230802. PubMed PMID: 37489248. [CrossRef]

- Yang C, Dong L, Zhong J. Immunomodulatory effects of iTr35 cell subpopulation and its research progress. Clin Exp Med. 2024;24(1):41. Epub 20240222. PubMed PMID: 38386086; PMCID: PMC10884179. [CrossRef]

- Koizumi SI, Ishikawa H. Transcriptional Regulation of Differentiation and Functions of Effector T Regulatory Cells. Cells. 2019;8(8). Epub 20190820. PubMed PMID: 31434282; PMCID: PMC6721668. [CrossRef]

- Li P, Liu C, Yu Z, Wu M. New Insights into Regulatory T Cells: Exosome- and Non-Coding RNA-Mediated Regulation of Homeostasis and Resident Treg Cells. Front Immunol. 2016;7:574. Epub 20161206. PubMed PMID: 27999575; PMCID: PMC5138199. [CrossRef]

- Korn T, Muschaweckh A. Stability and Maintenance of Foxp3(+) Treg Cells in Non-lymphoid Microenvironments. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2634. Epub 20191114. PubMed PMID: 31798580; PMCID: PMC6868061. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Rudra D. Emerging Functions of Regulatory T Cells in Tissue Homeostasis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:883. Epub 20180425. PubMed PMID: 29887862; PMCID: PMC5989423. [CrossRef]

- Boehm F, Martin M, Kesselring R, Schiechl G, Geissler EK, Schlitt HJ, Fichtner-Feigl S. Deletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in genetically targeted mice supports development of intestinal inflammation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:97. Epub 20120731. PubMed PMID: 22849659; PMCID: PMC3449180. [CrossRef]

- Collison LW, Pillai MR, Chaturvedi V, Vignali DA. Regulatory T cell suppression is potentiated by target T cells in a cell contact, IL-35- and IL-10-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):6121-8. PubMed PMID: 19414764; PMCID: PMC2698997. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura K, Kitani A, Strober W. Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med. 2001;194(5):629-44. PubMed PMID: 11535631; PMCID: PMC2195935. [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan P, Zheng L, Ishihara S, Reed J, Lenardo MJ. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(12):1353-62. Epub 20071104. PubMed PMID: 17982458. [CrossRef]

- Tekguc M, Wing JB, Osaki M, Long J, Sakaguchi S. Treg-expressed CTLA-4 depletes CD80/CD86 by trogocytosis, releasing free PD-L1 on antigen-presenting cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(30). PubMed PMID: 34301886; PMCID: PMC8325248. [CrossRef]

- Cross AR, Lion J, Poussin K, Glotz D, Mooney N. Inflammation Determines the Capacity of Allogenic Endothelial Cells to Regulate Human Treg Expansion. Front Immunol. 2021;12:666531. Epub 20210709. PubMed PMID: 34305898; PMCID: PMC8299527. [CrossRef]

- Kazanova A, Rudd CE. Programmed cell death 1 ligand (PD-L1) on T cells generates Treg suppression from memory. PLoS Biol. 2021;19(5):e3001272. Epub 20210519. PubMed PMID: 34010274; PMCID: PMC8168839. [CrossRef]

- Kondelkova K, Vokurkova D, Krejsek J, Borska L, Fiala Z, Ctirad A. Regulatory T cells (TREG) and their roles in immune system with respect to immunopathological disorders. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2010;53(2):73-7. PubMed PMID: 20672742. [CrossRef]

- Rocamora-Reverte L, Melzer FL, Wurzner R, Weinberger B. The Complex Role of Regulatory T Cells in Immunity and Aging. Front Immunol. 2020;11:616949. Epub 20210127. PubMed PMID: 33584708; PMCID: PMC7873351. [CrossRef]

- Workman CJ, Szymczak-Workman AL, Collison LW, Pillai MR, Vignali DA. The development and function of regulatory T cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(16):2603-22. Epub 20090424. PubMed PMID: 19390784; PMCID: PMC2715449. [CrossRef]

- Russler-Germain EV, Rengarajan S, Hsieh CS. Antigen-specific regulatory T-cell responses to intestinal microbiota. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(6):1375-86. Epub 20170802. PubMed PMID: 28766556; PMCID: PMC5939566. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25- naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198(12):1875-86. PubMed PMID: 14676299; PMCID: PMC2194145. [CrossRef]

- Duhen T, Duhen R, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Campbell DJ. Functionally distinct subsets of human FOXP3+ Treg cells that phenotypically mirror effector Th cells. Blood. 2012;119(19):4430-40. Epub 20120321. PubMed PMID: 22438251; PMCID: PMC3362361. [CrossRef]

- Koch MA, Thomas KR, Perdue NR, Smigiel KS, Srivastava S, Campbell DJ. T-bet(+) Treg cells undergo abortive Th1 cell differentiation due to impaired expression of IL-12 receptor beta2. Immunity. 2012;37(3):501-10. Epub 20120906. PubMed PMID: 22960221; PMCID: PMC3501343. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Chaudhry A, Kas A, deRoos P, Kim JM, Chu TT, Corcoran L, Treuting P, Klein U, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009;458(7236):351-6. Epub 20090201. PubMed PMID: 19182775; PMCID: PMC2864791. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Pastrana J, Shao Y, Chernaya V, Wang H, Yang XF. Epigenetic enzymes are the therapeutic targets for CD4(+)CD25(+/high)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Transl Res. 2015;165(1):221-40. Epub 20140815. PubMed PMID: 25193380; PMCID: PMC4259825. [CrossRef]

- Xu K, Yang WY, Nanayakkara GK, Shao Y, Yang F, Hu W, Choi ET, Wang H, Yang X. GATA3, HDAC6, and BCL6 Regulate FOXP3+ Treg Plasticity and Determine Treg Conversion into Either Novel Antigen-Presenting Cell-Like Treg or Th1-Treg. Front Immunol. 2018;9:45. Epub 20180126. PubMed PMID: 29434588; PMCID: PMC5790774. [CrossRef]

- Sole P, Yamanouchi J, Garnica J, Uddin MM, Clarke R, Moro J, Garabatos N, Thiessen S, Ortega M, Singha S, Mondal D, Fandos C, Saez-Rodriguez J, Yang Y, Serra P, Santamaria P. A T follicular helper cell origin for T regulatory type 1 cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2023;20(5):489-511. Epub 20230327. PubMed PMID: 36973489; PMCID: PMC10202951. [CrossRef]

- Loeff FC, Tsakok T, Dijk L, Hart MH, Duckworth M, Baudry D, Russell A, Dand N, van Leeuwen A, Griffiths CEM, Reynolds NJ, Barker J, Burden AD, Warren RB, de Vries A, Bloem K, Wolbink GJ, Smith CH, Rispens T, Badbir, Groups BS, consortium P. Clinical Impact of Antibodies against Ustekinumab in Psoriasis: An Observational, Cross-Sectional, Multicenter Study. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(11):2129-37. Epub 20200410. PubMed PMID: 32283057. [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt RL, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):385-93. Epub 20090301. PubMed PMID: 19252490; PMCID: PMC2714053. [CrossRef]

- Fu W, Liu X, Lin X, Feng H, Sun L, Li S, Chen H, Tang H, Lu L, Jin W, Dong C. Deficiency in T follicular regulatory cells promotes autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2018;215(3):815-25. Epub 20180129. PubMed PMID: 29378778; PMCID: PMC5839755. [CrossRef]

- Gagliani N, Amezcua Vesely MC, Iseppon A, Brockmann L, Xu H, Palm NW, de Zoete MR, Licona-Limon P, Paiva RS, Ching T, Weaver C, Zi X, Pan X, Fan R, Garmire LX, Cotton MJ, Drier Y, Bernstein B, Geginat J, Stockinger B, Esplugues E, Huber S, Flavell RA. Th17 cells transdifferentiate into regulatory T cells during resolution of inflammation. Nature. 2015;523(7559):221-5. Epub 20150429. PubMed PMID: 25924064; PMCID: PMC4498984. [CrossRef]

- Gregori S, Goudy KS, Roncarolo MG. The cellular and molecular mechanisms of immuno-suppression by human type 1 regulatory T cells. Front Immunol. 2012;3:30. Epub 20120229. PubMed PMID: 22566914; PMCID: PMC3342353. [CrossRef]

- Geginat J, Vasco C, Gruarin P, Bonnal R, Rossetti G, Silvestri Y, Carelli E, Pulvirenti N, Scantamburlo M, Moschetti G, Clemente F, Grassi F, Monticelli S, Pagani M, Abrignani S. Eomesodermin-expressing type 1 regulatory (EOMES(+) Tr1)-like T cells: Basic biology and role in immune-mediated diseases. Eur J Immunol. 2023;53(5):e2149775. Epub 20230317. PubMed PMID: 36653901. [CrossRef]

- Cui H, Wang N, Li H, Bian Y, Wen W, Kong X, Wang F. The dynamic shifts of IL-10-producing Th17 and IL-17-producing Treg in health and disease: a crosstalk between ancient "Yin-Yang" theory and modern immunology. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22(1):99. Epub 20240206. PubMed PMID: 38317142; PMCID: PMC10845554. [CrossRef]

- Wei X, Zhang J, Cui J, Xu W, Zhao G, Guo C, Yuan W, Zhou X, Ma J. Adaptive plasticity of natural interleukin-35-induced regulatory T cells (Tr35) that are required for T-cell immune regulation. Theranostics. 2024;14(7):2897-914. Epub 20240505. PubMed PMID: 38773985; PMCID: PMC11103508. [CrossRef]

- Anastassopoulou C, Ferous S, Medic S, Siafakas N, Boufidou F, Gioula G, Tsakris A. Vaccines for the Elderly and Vaccination Programs in Europe and the United States. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12(6). Epub 20240522. PubMed PMID: 38932295; PMCID: PMC11209271. [CrossRef]

- Palatella M, Guillaume SM, Linterman MA, Huehn J. The dark side of Tregs during aging. Front Immunol. 2022;13:940705. Epub 20220809. PubMed PMID: 36016952; PMCID: PMC9398463. [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Fernandez I, Rosado-Sanchez I, Alvarez-Rios AI, Galva MI, De Luna-Romero M, Sanbonmatsu-Gamez S, Perez-Ruiz M, Navarro-Mari JM, Carrillo-Vico A, Sanchez B, Ramos R, Canizares J, Leal M, Pacheco YM. Effect of homeostatic T-cell proliferation in the vaccine responsiveness against influenza in elderly people. Immun Ageing. 2019;16:14. Epub 20190705. PubMed PMID: 31312227; PMCID: PMC6612162. [CrossRef]

- Bodey B, Bodey B, Jr., Siegel SE, Kaiser HE. Involution of the mammalian thymus, one of the leading regulators of aging. In Vivo. 1997;11(5):421-40. PubMed PMID: 9427047.

- Chougnet CA, Tripathi P, Lages CS, Raynor J, Sholl A, Fink P, Plas DR, Hildeman DA. A major role for Bim in regulatory T cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2011;186(1):156-63. Epub 20101122. PubMed PMID: 21098226; PMCID: PMC3066029. [CrossRef]

- Raynor J, Sholl A, Plas DR, Bouillet P, Chougnet CA, Hildeman DA. IL-15 Fosters Age-Driven Regulatory T Cell Accrual in the Face of Declining IL-2 Levels. Front Immunol. 2013;4:161. Epub 20130624. PubMed PMID: 23805138; PMCID: PMC3690359. [CrossRef]

- Jagger A, Shimojima Y, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Regulatory T cells and the immune aging process: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2014;60(2):130-7. Epub 20131128. PubMed PMID: 24296590; PMCID: PMC4878402. [CrossRef]

- Lages CS, Suffia I, Velilla PA, Huang B, Warshaw G, Hildeman DA, Belkaid Y, Chougnet C. Functional regulatory T cells accumulate in aged hosts and promote chronic infectious disease reactivation. J Immunol. 2008;181(3):1835-48. PubMed PMID: 18641321; PMCID: PMC2587319. [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz D, Weyer S, Tolosa E, Gaenslen A, Berg D, Leyhe T, Gasser T, Stoltze L. Higher frequency of regulatory T cells in the elderly and increased suppressive activity in neurodegeneration. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;188(1-2):117-27. Epub 20070619. PubMed PMID: 17582512. [CrossRef]

- Agius E, Lacy KE, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Jagger AL, Papageorgiou AP, Hall S, Reed JR, Curnow SJ, Fuentes-Duculan J, Buckley CD, Salmon M, Taams LS, Krueger J, Greenwood J, Klein N, Rustin MH, Akbar AN. Decreased TNF-alpha synthesis by macrophages restricts cutaneous immunosurveillance by memory CD4+ T cells during aging. J Exp Med. 2009;206(9):1929-40. Epub 20090810. PubMed PMID: 19667063; PMCID: PMC2737169. [CrossRef]

- Gregg R, Smith CM, Clark FJ, Dunnion D, Khan N, Chakraverty R, Nayak L, Moss PA. The number of human peripheral blood CD4+ CD25high regulatory T cells increases with age. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140(3):540-6. PubMed PMID: 15932517; PMCID: PMC1809384. [CrossRef]

- Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, Shima T, Wing K, Niwa A, Parizot C, Taflin C, Heike T, Valeyre D, Mathian A, Nakahata T, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M, Amoura Z, Gorochov G, Sakaguchi S. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30(6):899-911. Epub 20090521. PubMed PMID: 19464196. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger B. Vaccines for the elderly: current use and future challenges. Immun Ageing. 2018;15:3. Epub 20180122. PubMed PMID: 29387135; PMCID: PMC5778733. [CrossRef]

- Batista-Duharte A, Pera A, Alino SF, Solana R. Regulatory T cells and vaccine effectiveness in older adults. Challenges and prospects. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;96:107761. Epub 20210601. PubMed PMID: 34162139. [CrossRef]

- Macatangay BJ, Szajnik ME, Whiteside TL, Riddler SA, Rinaldo CR. Regulatory T cell suppression of Gag-specific CD8 T cell polyfunctional response after therapeutic vaccination of HIV-1-infected patients on ART. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9852. Epub 20100324. PubMed PMID: 20352042; PMCID: PMC2844424. [CrossRef]

- Ndure J, Noho-Konteh F, Adetifa JU, Cox M, Barker F, Le MT, Sanyang LC, Drammeh A, Whittle HC, Clarke E, Plebanski M, Rowland-Jones SL, Flanagan KL. Negative Correlation between Circulating CD4(+)FOXP3(+)CD127(-) Regulatory T Cells and Subsequent Antibody Responses to Infant Measles Vaccine but Not Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis Vaccine Implies a Regulatory Role. Front Immunol. 2017;8:921. Epub 20170814. PubMed PMID: 28855899; PMCID: PMC5557771. [CrossRef]

- van der Geest KS, Abdulahad WH, Tete SM, Lorencetti PG, Horst G, Bos NA, Kroesen BJ, Brouwer E, Boots AM. Aging disturbs the balance between effector and regulatory CD4+ T cells. Exp Gerontol. 2014;60:190-6. Epub 20141107. PubMed PMID: 25449852. [CrossRef]

- Wang SM, Tsai MH, Lei HY, Wang JR, Liu CC. The regulatory T cells in anti-influenza antibody response post influenza vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(9):1243-9. Epub 20120816. PubMed PMID: 22894960; PMCID: PMC3579905. [CrossRef]

- Thorburn AN, Brown AC, Nair PM, Chevalier N, Foster PS, Gibson PG, Hansbro PM. Pneumococcal components induce regulatory T cells that attenuate the development of allergic airways disease by deviating and suppressing the immune response to allergen. J Immunol. 2013;191(8):4112-20. Epub 20130918. PubMed PMID: 24048894. [CrossRef]

- Jaron B, Maranghi E, Leclerc C, Majlessi L. Effect of attenuation of Treg during BCG immunization on anti-mycobacterial Th1 responses and protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2833. Epub 20080730. PubMed PMID: 18665224; PMCID: PMC2475666. [CrossRef]

- Klages K, Mayer CT, Lahl K, Loddenkemper C, Teng MW, Ngiow SF, Smyth MJ, Hamann A, Huehn J, Sparwasser T. Selective depletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells improves effective therapeutic vaccination against established melanoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70(20):7788-99. Epub 20101005. PubMed PMID: 20924102. [CrossRef]

- Garner-Spitzer E, Wagner A, Paulke-Korinek M, Kollaritsch H, Heinz FX, Redlberger-Fritz M, Stiasny K, Fischer GF, Kundi M, Wiedermann U. Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) and hepatitis B nonresponders feature different immunologic mechanisms in response to TBE and influenza vaccination with involvement of regulatory T and B cells and IL-10. J Immunol. 2013;191(5):2426-36. Epub 20130719. PubMed PMID: 23872054. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty NG, Chattopadhyay S, Mehrotra S, Chhabra A, Mukherji B. Regulatory T-cell response and tumor vaccine-induced cytotoxic T lymphocytes in human melanoma. Hum Immunol. 2004;65(8):794-802. PubMed PMID: 15336780. [CrossRef]

- Wen Z, Wang X, Dong K, Zhang H, Bu Z, Ye L, Yang C. Blockage of regulatory T cells augments induction of protective immune responses by influenza virus-like particles in aged mice. Microbes Infect. 2017;19(12):626-34. Epub 20170909. PubMed PMID: 28899815; PMCID: PMC5726911. [CrossRef]

- Lin PH, Wong WI, Wang YL, Hsieh MP, Lu CW, Liang CY, Jui SH, Wu FY, Chen PJ, Yang HC. Vaccine-induced antigen-specific regulatory T cells attenuate the antiviral immunity against acute influenza virus infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11(4):1239-53. Epub 20180221. PubMed PMID: 29467445. [CrossRef]

- Toka FN, Suvas S, Rouse BT. CD4+ CD25+ T cells regulate vaccine-generated primary and memory CD8+ T-cell responses against herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 2004;78(23):13082-9. PubMed PMID: 15542660; PMCID: PMC525021. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza Mora MR, Steeg C, Tartz S, Heussler V, Sparwasser T, Link A, Fleischer B, Jacobs T. Depletion of regulatory T cells augments a vaccine-induced T effector cell response against the liver-stage of malaria but fails to increase memory. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104627. Epub 20140812. PubMed PMID: 25115805; PMCID: PMC4130546. [CrossRef]

- Stein P, Weber M, Prufer S, Schmid B, Schmitt E, Probst HC, Waisman A, Langguth P, Schild H, Radsak MP. Regulatory T cells and IL-10 independently counterregulate cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses induced by transcutaneous immunization. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27911. Epub 20111116. PubMed PMID: 22114725; PMCID: PMC3218067. [CrossRef]

- Liao H, Peng X, Gan L, Feng J, Gao Y, Yang S, Hu X, Zhang L, Yin Y, Wang H, Xu X. Protective Regulatory T Cell Immune Response Induced by Intranasal Immunization With the Live-Attenuated Pneumococcal Vaccine SPY1 via the Transforming Growth Factor-beta1-Smad2/3 Pathway. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1754. Epub 20180802. PubMed PMID: 30116243; PMCID: PMC6082925. [CrossRef]

- Dhawan M, Rabaan AA, Alwarthan S, Alhajri M, Halwani MA, Alshengeti A, Najim MA, Alwashmi ASS, Alshehri AA, Alshamrani SA, AlShehail BM, Garout M, Al-Abdulhadi S, Al-Ahmed SH, Thakur N, Verma G. Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) and COVID-19: Unveiling the Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potentialities with a Special Focus on Long COVID. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(3). Epub 20230319. PubMed PMID: 36992283; PMCID: PMC10059134. [CrossRef]

- Franco A, Song J, Chambers C, Sette A, Grifoni A. SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific regulatory T cells (Treg) expand and develop memory in vaccine recipients suggesting a role for immune regulation in preventing severe symptoms in COVID-19. Autoimmunity. 2023;56(1):2259133. Epub 20230919. PubMed PMID: 37724524. [CrossRef]

- Bekbolsynov D, Waack A, Buskey C, Bhadkamkar S, Rengel K, Petersen W, Brown ML, Sparkle T, Kaw D, Syed FJ, Chattopadhyay S, Chakravarti R, Khuder S, Mierzejewska B, Rees M, Stepkowski S. Differences in Responses of Immunosuppressed Kidney Transplant Patients to Moderna mRNA-1273 versus Pfizer-BioNTech. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12(1). Epub 20240117. PubMed PMID: 38250904; PMCID: PMC10819652. [CrossRef]

- Amr AEE, Abo-Ghalia MH, Moustafa GO, Al-Omar MA, Nossier ES, Elsayed EA. Design, Synthesis and Docking Studies of Novel Macrocyclic Pentapeptides as Anticancer Multi-Targeted Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules. 2018;23(10). Epub 20180920. PubMed PMID: 30241374; PMCID: PMC6222410. [CrossRef]

- Zou ML, Chen ZH, Teng YY, Liu SY, Jia Y, Zhang KW, Sun ZL, Wu JJ, Yuan ZD, Feng Y, Li X, Xu RS, Yuan FL. The Smad Dependent TGF-beta and BMP Signaling Pathway in Bone Remodeling and Therapies. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:593310. Epub 20210505. PubMed PMID: 34026818; PMCID: PMC8131681. [CrossRef]

- Brezar V, Godot V, Cheng L, Su L, Levy Y, Seddiki N. T-Regulatory Cells and Vaccination "Pay Attention and Do Not Neglect Them": Lessons from HIV and Cancer Vaccine Trials. Vaccines (Basel). 2016;4(3). Epub 20160905. PubMed PMID: 27608046; PMCID: PMC5041024. [CrossRef]

- Dinc R. Leishmania Vaccines: the Current Situation with Its Promising Aspect for the Future. Korean J Parasitol. 2022;60(6):379-91. Epub 20221222. PubMed PMID: 36588414; PMCID: PMC9806502. [CrossRef]

- Muller A, Solnick JV. Inflammation, immunity, and vaccine development for Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2011;16 Suppl 1:26-32. PubMed PMID: 21896082. [CrossRef]

- Dyck L, Wilk MM, Raverdeau M, Misiak A, Boon L, Mills KH. Anti-PD-1 inhibits Foxp3(+) Treg cell conversion and unleashes intratumoural effector T cells thereby enhancing the efficacy of a cancer vaccine in a mouse model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65(12):1491-8. Epub 20160928. PubMed PMID: 27680570; PMCID: PMC11028992. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg A, Canniff J, Rouphael N, Mehta A, Mulligan M, Whitaker JA, Levin MJ. Varicella-Zoster Virus-Specific Cellular Immune Responses to the Live Attenuated Zoster Vaccine in Young and Older Adults. J Immunol. 2017;199(2):604-12. Epub 20170612. PubMed PMID: 28607114; PMCID: PMC5505810. [CrossRef]

- Sellars MC, Wu CJ, Fritsch EF. Cancer vaccines: Building a bridge over troubled waters. Cell. 2022;185(15):2770-88. Epub 20220713. PubMed PMID: 35835100; PMCID: PMC9555301. [CrossRef]

- Strum S, Andersen MH, Svane IM, Siu LL, Weber JS. State-Of-The-Art Advancements on Cancer Vaccines and Biomarkers. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2024;44(3):e438592. PubMed PMID: 38669611. [CrossRef]

- Lahl K, Sparwasser T. In vivo depletion of FoxP3+ Tregs using the DEREG mouse model. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;707:157-72. PubMed PMID: 21287334. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Targeting Treg cells in cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2019;49(8):1140-6. Epub 20190705. PubMed PMID: 31257581. [CrossRef]

- Solomon I, Amann M, Goubier A, Arce Vargas F, Zervas D, Qing C, Henry JY, Ghorani E, Akarca AU, Marafioti T, Sledzinska A, Werner Sunderland M, Franz Demane D, Clancy JR, Georgiou A, Salimu J, Merchiers P, Brown MA, Flury R, Eckmann J, Murgia C, Sam J, Jacobsen B, Marrer-Berger E, Boetsch C, Belli S, Leibrock L, Benz J, Koll H, Sutmuller R, Peggs KS, Quezada SA. CD25-T(reg)-depleting antibodies preserving IL-2 signaling on effector T cells enhance effector activation and antitumor immunity. Nat Cancer. 2020;1(12):1153-66. Epub 20201109. PubMed PMID: 33644766; PMCID: PMC7116816. [CrossRef]

- Harbecke R, Cohen JI, Oxman MN. Herpes Zoster Vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(12 Suppl 2):S429-S42. PubMed PMID: 34590136; PMCID: PMC8482024. [CrossRef]

- Romeli S, Hassan SS, Yap WB. Multi-Epitope Peptide-Based and Vaccinia-Based Universal Influenza Vaccine Candidates Subjected to Clinical Trials. Malays J Med Sci. 2020;27(2):10-20. Epub 20200430. PubMed PMID: 32788837; PMCID: PMC7409566. [CrossRef]

- Rutigliano JA, Sharma S, Morris MY, Oguin TH, 3rd, McClaren JL, Doherty PC, Thomas PG. Highly pathological influenza A virus infection is associated with augmented expression of PD-1 by functionally compromised virus-specific CD8+ T cells. J Virol. 2014;88(3):1636-51. Epub 20131120. PubMed PMID: 24257598; PMCID: PMC3911576. [CrossRef]

- Caselli E, Boni M, Di Luca D, Salvatori D, Vita A, Cassai E. A combined bovine herpesvirus 1 gB-gD DNA vaccine induces immune response in mice. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;28(2):155-66. PubMed PMID: 15582691. [CrossRef]

- Furuichi Y, Tokuyama H, Ueha S, Kurachi M, Moriyasu F, Kakimi K. Depletion of CD25+CD4+T cells (Tregs) enhances the HBV-specific CD8+ T cell response primed by DNA immunization. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(24):3772-7. PubMed PMID: 15968737; PMCID: PMC4316033. [CrossRef]

- Quinn KM, McHugh RS, Rich FJ, Goldsack LM, de Lisle GW, Buddle BM, Delahunt B, Kirman JR. Inactivation of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells during early mycobacterial infection increases cytokine production but does not affect pathogen load. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84(5):467-74. Epub 20060720. PubMed PMID: 16869940. [CrossRef]

- Litjens NH, Boer K, Betjes MG. Identification of circulating human antigen-reactive CD4+ FOXP3+ natural regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2012;188(3):1083-90. Epub 20111221. PubMed PMID: 22190183. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Wang L, Niu W, Wu Y, Zhang J, Meng G. Increased CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the blood of nonresponders after standard hepatitis B surface antigen vaccine immunization. Clin Immunol. 2008;127(2):265-6. Epub 20080304. PubMed PMID: 18304878. [CrossRef]

- Yang Z, Wang S, Zhang J, Wang L, Wu Y. Expression of PD-1 is up-regulated in CD4+CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cell of non-responders after hepatitis B surface antigen vaccine immunization. Clin Immunol. 2008;129(1):176-7. Epub 20080815. PubMed PMID: 18707923. [CrossRef]

- Correale J, Farez M, Razzitte G. Helminth infections associated with multiple sclerosis induce regulatory B cells. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(2):187-99. PubMed PMID: 18655096. [CrossRef]

- Duddy M, Niino M, Adatia F, Hebert S, Freedman M, Atkins H, Kim HJ, Bar-Or A. Distinct effector cytokine profiles of memory and naive human B cell subsets and implication in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2007;178(10):6092-9. PubMed PMID: 17475834. [CrossRef]

- Blair PA, Norena LY, Flores-Borja F, Rawlings DJ, Isenberg DA, Ehrenstein MR, Mauri C. CD19(+)CD24(hi)CD38(hi) B cells exhibit regulatory capacity in healthy individuals but are functionally impaired in systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients. Immunity. 2010;32(1):129-40. Epub 20100114. PubMed PMID: 20079667. [CrossRef]

- Anolik JH, Barnard J, Owen T, Zheng B, Kemshetti S, Looney RJ, Sanz I. Delayed memory B cell recovery in peripheral blood and lymphoid tissue in systemic lupus erythematosus after B cell depletion therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):3044-56. PubMed PMID: 17763423. [CrossRef]

- Newell KA, Asare A, Kirk AD, Gisler TD, Bourcier K, Suthanthiran M, Burlingham WJ, Marks WH, Sanz I, Lechler RI, Hernandez-Fuentes MP, Turka LA, Seyfert-Margolis VL, Immune Tolerance Network STSG. Identification of a B cell signature associated with renal transplant tolerance in humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):1836-47. Epub 20100524. PubMed PMID: 20501946; PMCID: PMC2877933. [CrossRef]

- Das A, Ellis G, Pallant C, Lopes AR, Khanna P, Peppa D, Chen A, Blair P, Dusheiko G, Gill U, Kennedy PT, Brunetto M, Lampertico P, Mauri C, Maini MK. IL-10-producing regulatory B cells in the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Immunol. 2012;189(8):3925-35. Epub 20120912. PubMed PMID: 22972930; PMCID: PMC3480715. [CrossRef]

- Lemoine S, Morva A, Youinou P, Jamin C. Human T cells induce their own regulation through activation of B cells. J Autoimmun. 2011;36(3-4):228-38. Epub 20110212. PubMed PMID: 21316922. [CrossRef]

- Asseman C, Mauze S, Leach MW, Coffman RL, Powrie F. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 1999;190(7):995-1004. PubMed PMID: 10510089; PMCID: PMC2195650. [CrossRef]

- Durando P, Iudici R, Alicino C, Alberti M, de Florentis D, Ansaldi F, Icardi G. Adjuvants and alternative routes of administration towards the development of the ideal influenza vaccine. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7 Suppl:29-40. Epub 20110101. PubMed PMID: 21245655. [CrossRef]

- Crooke SN, Ovsyannikova IG, Poland GA, Kennedy RB. Immunosenescence: A systems-level overview of immune cell biology and strategies for improving vaccine responses. Exp Gerontol. 2019;124:110632. Epub 20190613. PubMed PMID: 31201918; PMCID: PMC6849399. [CrossRef]

- Li APY, Cohen CA, Leung NHL, Fang VJ, Gangappa S, Sambhara S, Levine MZ, Iuliano AD, Perera R, Ip DKM, Peiris JSM, Thompson MG, Cowling BJ, Valkenburg SA. Immunogenicity of standard, high-dose, MF59-adjuvanted, and recombinant-HA seasonal influenza vaccination in older adults. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6(1):25. Epub 20210216. PubMed PMID: 33594050; PMCID: PMC7886864. [CrossRef]

- Winokur P, El Sahly HM, Mulligan MJ, Frey SE, Rupp R, Anderson EJ, Edwards KM, Bernstein DI, Schmader K, Jackson LA, Chen WH, Hill H, Bellamy A, Group DHNVS. Immunogenicity and safety of different dose schedules and antigen doses of an MF59-adjuvanted H7N9 vaccine in healthy adults aged 65 years and older. Vaccine. 2021;39(8):1339-48. Epub 20210121. PubMed PMID: 33485646; PMCID: PMC8504682. [CrossRef]

- Pelton SI, Divino V, Shah D, Mould-Quevedo J, DeKoven M, Krishnarajah G, Postma MJ. Evaluating the Relative Vaccine Effectiveness of Adjuvanted Trivalent Influenza Vaccine Compared to High-Dose Trivalent and Other Egg-Based Influenza Vaccines among Older Adults in the US during the 2017-2018 Influenza Season. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(3). Epub 20200807. PubMed PMID: 32784684; PMCID: PMC7563546. [CrossRef]

- Kodali L, Budhiraja P, Gea-Banacloche J. COVID-19 in kidney transplantation-implications for immunosuppression and vaccination. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1060265. Epub 20221123. PubMed PMID: 36507509; PMCID: PMC9727141. [CrossRef]

- Tylicki L, Debska-Slizien A, Muchlado M, Slizien Z, Golebiewska J, Dabrowska M, Biedunkiewicz B. Boosting Humoral Immunity from mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;10(1). Epub 20211231. PubMed PMID: 35062717; PMCID: PMC8779302. [CrossRef]

- DiazGranados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M, Kirby D, Treanor J, Collins A, Pollak R, Christoff J, Earl J, Landolfi V, Martin E, Gurunathan S, Nathan R, Greenberg DP, Tornieporth NG, Decker MD, Talbot HK. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):635-45. PubMed PMID: 25119609. [CrossRef]

- Icardi G, Orsi A, Ceravolo A, Ansaldi F. Current evidence on intradermal influenza vaccines administered by Soluvia licensed micro injection system. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(1):67-75. Epub 20120101. PubMed PMID: 22293531; PMCID: PMC3350142. [CrossRef]

- Chi RC, Rock MT, Neuzil KM. Immunogenicity and safety of intradermal influenza vaccination in healthy older adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(10):1331-8. PubMed PMID: 20377407. [CrossRef]

- Verma SK, Mahajan P, Singh NK, Gupta A, Aggarwal R, Rappuoli R, Johri AK. New-age vaccine adjuvants, their development, and future perspective. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1043109. Epub 20230224. PubMed PMID: 36911719; PMCID: PMC9998920. [CrossRef]

- Podda A. The adjuvanted influenza vaccines with novel adjuvants: experience with the MF59-adjuvanted vaccine. Vaccine. 2001;19(17-19):2673-80. PubMed PMID: 11257408. [CrossRef]

- O'Hagan DT, Wack A, Podda A. MF59 is a safe and potent vaccine adjuvant for flu vaccines in humans: what did we learn during its development? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82(6):740-4. Epub 20071031. PubMed PMID: 17971820. [CrossRef]

- Vesikari T, Pellegrini M, Karvonen A, Groth N, Borkowski A, O'Hagan DT, Podda A. Enhanced immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccines in young children using MF59 adjuvant. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(7):563-71. PubMed PMID: 19561422. [CrossRef]

- Heineman TC, Clements-Mann ML, Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Izu AE, Sakamoto D, Eiden J, Van Nest GA, Hsu HH. A randomized, controlled study in adults of the immunogenicity of a novel hepatitis B vaccine containing MF59 adjuvant. Vaccine. 1999;17(22):2769-78. PubMed PMID: 10438046. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson I, Bugarini R, Nicholson KG, Podda A, Wood JM, Zambon MC, Katz JM. Cross-reactivity to highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 viruses after vaccination with nonadjuvanted and MF59-adjuvanted influenza A/Duck/Singapore/97 (H5N3) vaccine: a potential priming strategy. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(8):1210-5. Epub 20050314. PubMed PMID: 15776364. [CrossRef]

- Seubert A, Monaci E, Pizza M, O'Hagan DT, Wack A. The adjuvants aluminum hydroxide and MF59 induce monocyte and granulocyte chemoattractants and enhance monocyte differentiation toward dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2008;180(8):5402-12. PubMed PMID: 18390722. [CrossRef]

- Garcon N, Vaughn DW, Didierlaurent AM. Development and evaluation of AS03, an Adjuvant System containing alpha-tocopherol and squalene in an oil-in-water emulsion. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11(3):349-66. PubMed PMID: 22380826. [CrossRef]

- Diez-Domingo J, Garces-Sanchez M, Baldo JM, Planelles MV, Ubeda I, JuBert A, Mares J, Moris P, Garcia-Corbeira P, Drame M, Gillard P. Immunogenicity and Safety of H5N1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (Clade 1) AS03-adjuvanted prepandemic candidate influenza vaccines in children aged 3 to 9 years: a phase ii, randomized, open, controlled study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(6):e35-46. PubMed PMID: 20375709. [CrossRef]

- Carmona Martinez A, Salamanca de la Cueva I, Boutet P, Vanden Abeele C, Smolenov I, Devaster JM. A phase 1, open-label safety and immunogenicity study of an AS03-adjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in children aged 6 to 35 months. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(7):1959-68. PubMed PMID: 25424805; PMCID: PMC4186022. [CrossRef]

- Wilkins AL, Kazmin D, Napolitani G, Clutterbuck EA, Pulendran B, Siegrist CA, Pollard AJ. AS03- and MF59-Adjuvanted Influenza Vaccines in Children. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1760. Epub 20171213. PubMed PMID: 29326687; PMCID: PMC5733358. [CrossRef]

- Garcon N, Di Pasquale A. From discovery to licensure, the Adjuvant System story. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(1):19-33. Epub 20160916. PubMed PMID: 27636098; PMCID: PMC5287309. [CrossRef]

- Alving CR, Peachman KK, Matyas GR, Rao M, Beck Z. Army Liposome Formulation (ALF) family of vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(3):279-92. Epub 20200331. PubMed PMID: 32228108; PMCID: PMC7412170. [CrossRef]

- Genito CJ, Beck Z, Phares TW, Kalle F, Limbach KJ, Stefaniak ME, Patterson NB, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Waters NC, Matyas GR, Alving CR, Dutta S. Liposomes containing monophosphoryl lipid A and QS-21 serve as an effective adjuvant for soluble circumsporozoite protein malaria vaccine FMP013. Vaccine. 2017;35(31):3865-74. Epub 20170607. PubMed PMID: 28596090. [CrossRef]

- Beck Z, Torres OB, Matyas GR, Lanar DE, Alving CR. Immune response to antigen adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide particles: Effects of co-adsorption of ALF or ALFQ adjuvant to the aluminum-antigen complex. J Control Release. 2018;275:12-9. Epub 20180209. PubMed PMID: 29432824; PMCID: PMC5878139. [CrossRef]

- Beck Z, Matyas GR, Jalah R, Rao M, Polonis VR, Alving CR. Differential immune responses to HIV-1 envelope protein induced by liposomal adjuvant formulations containing monophosphoryl lipid A with or without QS21. Vaccine. 2015;33(42):5578-87. Epub 20150913. PubMed PMID: 26372857. [CrossRef]

- Moser C, Amacker M, Kammer AR, Rasi S, Westerfeld N, Zurbriggen R. Influenza virosomes as a combined vaccine carrier and adjuvant system for prophylactic and therapeutic immunizations. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6(5):711-21. PubMed PMID: 17931152. [CrossRef]

- Arkema A, Huckriede A, Schoen P, Wilschut J, Daemen T. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity by fusion-active peptide-containing virosomes. Vaccine. 2000;18(14):1327-33. PubMed PMID: 10618529. [CrossRef]

- Batista-Duharte A, Tellez-Martinez D, Fuentes DLP, Carlos IZ. Molecular adjuvants that modulate regulatory T cell function in vaccination: A critical appraisal. Pharmacol Res. 2018;129:237-50. Epub 20171122. PubMed PMID: 29175113. [CrossRef]

- Ndure J, Flanagan KL. Targeting regulatory T cells to improve vaccine immunogenicity in early life. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:477. Epub 20140911. PubMed PMID: 25309517; PMCID: PMC4161046. [CrossRef]

- Curreri A, Sankholkar D, Mitragotri S, Zhao Z. RNA therapeutics in the clinic. Bioeng Transl Med. 2023;8(1):e10374. Epub 20220706. PubMed PMID: 36684099; PMCID: PMC9842029. [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak T, Curran MA. 4-1BB Agonists: Multi-Potent Potentiators of Tumor Immunity. Front Oncol. 2015;5:117. Epub 20150608. PubMed PMID: 26106583; PMCID: PMC4459101. [CrossRef]

- Bartkowiak T, Singh S, Yang G, Galvan G, Haria D, Ai M, Allison JP, Sastry KJ, Curran MA. Unique potential of 4-1BB agonist antibody to promote durable regression of HPV+ tumors when combined with an E6/E7 peptide vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(38):E5290-9. Epub 20150908. PubMed PMID: 26351680; PMCID: PMC4586868. [CrossRef]

- Bullock TNJ. CD40 stimulation as a molecular adjuvant for cancer vaccines and other immunotherapies. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(1):14-22. Epub 20210719. PubMed PMID: 34282297; PMCID: PMC8752810. [CrossRef]

- Chu Y, Li R, Qian L, Liu F, Xu R, Meng F, Ke Y, Shao J, Yu L, Liu Q, Liu B. Tumor eradicated by combination of imiquimod and OX40 agonist for in situ vaccination. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(11):4490-500. Epub 20210927. PubMed PMID: 34537997; PMCID: PMC8586665. [CrossRef]

- Paston SJ, Brentville VA, Symonds P, Durrant LG. Cancer Vaccines, Adjuvants, and Delivery Systems. Front Immunol. 2021;12:627932. Epub 20210330. PubMed PMID: 33859638; PMCID: PMC8042385. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs JF, Punt CJ, Lesterhuis WJ, Sutmuller RP, Brouwer HM, Scharenborg NM, Klasen IS, Hilbrands LB, Figdor CG, de Vries IJ, Adema GJ. Dendritic cell vaccination in combination with anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody treatment: a phase I/II study in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(20):5067-78. Epub 20100824. PubMed PMID: 20736326. [CrossRef]

- Webster RG, Govorkova EA. Continuing challenges in influenza. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1323(1):115-39. Epub 20140530. PubMed PMID: 24891213; PMCID: PMC4159436. [CrossRef]

- Pavlicevic M, Marmiroli N, Maestri E. Immunomodulatory peptides-A promising source for novel functional food production and drug discovery. Peptides. 2022;148:170696. Epub 20211129. PubMed PMID: 34856531. [CrossRef]

- Du PY, Gandhi A, Bawa M, Gromala J. The ageing immune system as a potential target of senolytics. Oxf Open Immunol. 2023;4(1):iqad004. Epub 20230503. PubMed PMID: 37255929; PMCID: PMC10191675. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Gower AC, Ding H, Giorgadze N, Palmer AK, Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Lenburg M, O'Hara SP, LaRusso NF, Miller JD, Roos CM, Verzosa GC, LeBrasseur NK, Wren JD, Farr JN, Khosla S, Stout MB, McGowan SJ, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H, Gurkar AU, Zhao J, Colangelo D, Dorronsoro A, Ling YY, Barghouthy AS, Navarro DC, Sano T, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Kirkland JL. The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell. 2015;14(4):644-58. Epub 20150422. PubMed PMID: 25754370; PMCID: PMC4531078. [CrossRef]

| T cell subsets | Markers | Localization | Homing chemokines and their receptors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T naïve | CD25-, CD45RA+, CD45RO-, CD127+ | LN, Spleen, Blood, efferent lymphatics | CCL19+, CCL21+ | von Andrian et al. 2010 [18] |

| Tcm | CD25+, CD45RA+, CD45RO+, CD127+ | LN. Spleen, Blood, efferent lymphatics | CCR7+, CD62L+, S1pr1+ | Sallusto et al. 2014 [19] |

| Tem | CD25+, CD45RA-, CD45RO+, CD127+ | Tissues, afferent lymphatics | CCR7-, CD62L- | Sallusto et al. 2014 [19] |

| Trm | CD103+, CD69+, CD122- | Tissue Resident | CCR7-, CD62L-, S1pr1, CXCL10+ | Schenkel et al. 2014 [17], Yenyuwadee et al. 2022 [20] |

| T regulatory cells | Origin | Markers | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| tTreg | Thymus (central) | CCR7, CD45RA, CD31, SELL, NRP1, Foxp3+ | Luo, Xue, Wang et al. 2019 [34], |

| pTreg | Peripheral | GATA3, IRF4, RORC, TBX21, HELIOS, Foxp3+ | Zheng, Wang, Horwitz et al. 2008 [35] |

| iTreg | Peripheral | Treg-specific demethylation region (TSDR), Foxp3+ | Zheng, Wang, Horwitz et al. 2008 [35] |

| Th1-Treg | Peripheral | CXCR, Tbet, Foxp3+ | Halim et al. 2017 [36] |

| Th2-Treg | Peripheral | IL-4, IL-13, IRF4, Foxp3+ | Halim et al. 2017 [36] |

| Th17-Treg | Peripheral | CD161, CCR6+, IL17A, IL23R, IL-12Rβ2, Fox3p+ | Romagnani et al. 2009 [37] |

| Tfh-Treg | Peripheral | CXCR5, Bcl-6, IL-21, Foxp3+ | Chung et al. 2011 [38] |

| Tr1 | Peripheral | IL-10, CD49b, Lag3, Foxp– | Suhrkamp et al. 2023 [39] |

| Tr35 | Peripheral | IL-35, IL-10, p35, EB13, IL-12b2, gp130, Foxp3- | Yang, Dong, Zhong et al. 2024 [40] |

| Type | Clinically approved vaccines | Vaccines under development | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Human observational study or clinical trial | Mouse Treg depletion | Human observational study or clinical trial | Mouse Treg depletion |

| Message | High Treg levels are detrimental to vaccine efficacy | Treg depletion rescues vaccination | Tregs presence is detrimental to vaccine efficacy | Treg depletion rescues vaccination |

| References | Macatangay et al. 2010 [85]; Ndure et al. 2017 [86]; vander_Geest, et al. 2014 [87]; Wang et al. 2012 [88]. |

Thorburn et al. 2013 [89]; Jaron et al. 2008 [90]; Klages et al. 2010 [91]. |

Garner-Spitzer et al. 2013 [92]; Chakraborty et al 2004 [93]. |

Wen et al. 2017 [94]; Lin et al. 2018 [95]; Toka et al. 2004 [96]; Mora et al. 2014 [97]; Weber et al. 2011 [98]; Liao et al. 2018 [99]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).