Submitted:

18 July 2024

Posted:

19 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methodology

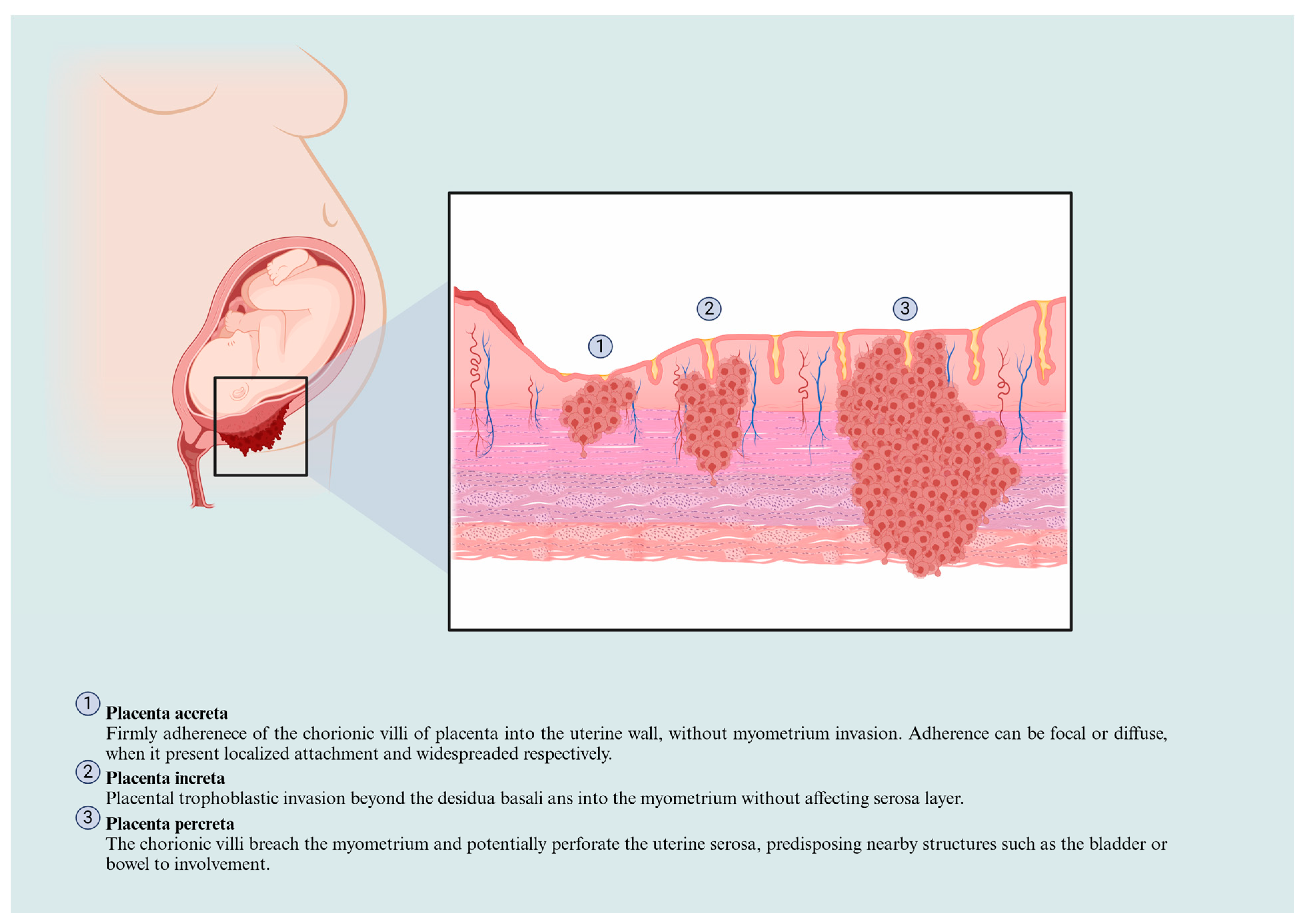

Placenta Accreta Spectrum Classification and Physiopathological Features

Biomarkers Associated with Placenta Accreta Development

Molecular Mechanisms Involved in the Placenta Acreta Spectrum

5.Gene Expression

5.The Roles of Non-Coding RNAs in the PAS

5.2.microRNAs

5.2.Long Non-Coding RNAs

Aberrant Signaling Pathways in the Placenta Accreta Spectrum

Perspectives and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carrillo, A.P.; Chandraharan, E. Placenta accreta spectrum: Risk factors, diagnosis and management with special reference to the Triple P procedure. Women's Health 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, A.G.; Beigi, R.; Heine, P.; Silver, R.M.; Wax, J.R. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 7: Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, e259–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, A.G.; Bardsley, T.R.; Greene, T.; Varner, M.W.; Silver, R.M.; Bowman, Z.S. Risk Factors for Placenta Accreta: A Large Prospective Cohort. Am. J. Perinatol. 2013, 31, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, N.E.; Fu, R.; Guise, J.-M. Impact of multiple cesarean deliveries on maternal morbidity: a systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 205, 262.e1–262.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauniaux, E.; Jurkovic, D. Placenta accreta: Pathogenesis of a 20th century iatrogenic uterine disease. Placenta 2012, 33, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauniaux, E.; Chantraine, F.; Silver, R.M.; Langhoff-Roos, J. for the FIGO Placenta Accreta Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Panel FIGO consensus guidelines on placenta accreta spectrum disorders: Epidemiology. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 140, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betrán, A.P.; Ye, J.; Moller, A.-B.; Zhang, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Torloni, M.R. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0148343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Zhang, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Torloni, M.R.; Gülmezoglu, A.; Betran, A. Association between rates of caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st century: a worldwide population-based ecological study with longitudinal data. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 123, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calagna, G.; Polito, S.; Labate, F.; Guiglia, R.A.; De Maria, F.; Bisso, C.; Cucinella, G.; Calì, G. Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorder in a Patient with Six Previous Caesarean Deliveries: Step by Step Management. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 2021, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beekhuizen, H.J.; Stefanovic, V.; Schwickert, A.; Henrich, W.; Fox, K.A.; Gziri, M.M.; Sentilhes, L.; Gronbeck, L.; Chantraine, F.; Morel, O.; et al. A multicenter observational survey of management strategies in 442 pregnancies with suspected placenta accreta spectrum. Acta Obstet. et Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, H.; Ma, J.; Dou, R.; Zhao, X.; Yan, J.; Yang, H. Validation of a scoring system for prediction of obstetric complications in placenta accreta spectrum disorders. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2021, 35, 4149–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, H.C.; Postle, J.D.; Downey, P.; Brennan, D.J. Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Review of Pathology, Molecular Biology, and Biomarkers. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlQasem, M.H.; Shaamash, A.H.; Al Ghamdi, D.S.; Mahfouz, A.A.; Eskandar, M.A. Incidence, risk factors, and maternal outcomes of major degree placenta previa. SciVee 2023, 44, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, C.H.J.R.; Kastelein, A.W.; Kleinrouweler, C.E.; Van Leeuwen, E.; De Jong, K.H.; Pajkrt, E.; Van Noorden, C.J.F. Development of placental abnormalities in location and anatomy. Acta Obstet. et Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; A Lorca, R.; Su, E.J. Molecular and cellular underpinnings of normal and abnormal human placental blood flows. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2018, 60, R9–R22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morlando, M.; Collins, S. Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorders: Challenges, Risks, and Management Strategies. Int. J. Women's Heal. 2020; 12, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, V.; Verde, F.; Sarno, L.; Migliorini, S.; Petretta, M.; Mainenti, P.P.; D’armiento, M.; Guida, M.; Brunetti, A.; Maurea, S. Prediction of placenta accreta spectrum in patients with placenta previa using clinical risk factors, ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging findings. La Radiol. medica 2021, 126, 1216–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Yuan, X.; Tong, C.; Qi, H. What we know about placenta accreta spectrum (PAS). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 259, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, J.L.; Baergen, R.; Ernst, L.M.; Katzman, P.J.; Jacques, S.M.; Jauniaux, E.; Khong, T.Y.; Metlay, L.A.; Poder, L.; Qureshi, F.; et al. Classification and reporting guidelines for the pathology diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders: recommendations from an expert panel. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 2382–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shainker, S.A.; Silver, R.M.; Modest, A.M.; Hacker, M.R.; Hecht, J.L.; Salahuddin, S.; Dillon, S.T.; Ciampa, E.J.; D'Alton, M.E.; Otu, H.H.; et al. Placenta accreta spectrum: biomarker discovery using plasma proteomics. In Proceedings of the Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2020/9//, 2020; pp. 433.e431-433.e414.

- Zhang, T.; Wang, S. Potential Serum Biomarkers in Prenatal Diagnosis of Placenta Accreta Spectrum. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 860186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezowsky, A.; Pardo, J.; Ben-Zion, M.; Wiznitzer, A.; Aviram, A. Second Trimester Biochemical Markers as Possible Predictors of Pathological Placentation: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2019, 46, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztas, E.; Ozler, S.; Caglar, A.T.; Yucel, A. Analysis of first and second trimester maternal serum analytes for the prediction of morbidly adherent placenta requiring hysterectomy. Kaohsiung J. Med Sci. 2016, 32, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumbanraja S; Yaznil MR; Siahaan AM; Berry Eka Parda B. Soluble FMS-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1: Role in placenta accreta spectrum disorder. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Gu, M.; Chen, P.; Wan, S.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, Y.; Li, L. Distinguishing placenta accreta from placenta previa via maternal plasma levels of sFlt-1 and PLGF and the sFlt-1/PLGF ratio. Placenta 2022, 124, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büke, B.; Akkaya, H.; Demir, S.; Sağol, S.; Şimşek, D.; Başol, G.; Barutçuoğlu, B. Relationship between first trimester aneuploidy screening test serum analytes and placenta accreta. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2017, 31, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Yan, P.; Ye, Y.; Peng, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.T. Maternal plasma levels of cell-free β-HCG mRNA as a prenatal diagnostic indicator of placenta accrete. Placenta 2014, 35, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, A.; Akbarzadeh-Jahromi, M.; Bahrami, S.; Gharamani, S.; Shahraki, H.R.; Kasraeian, M.; Vafaei, H.; Zare, M.; Asadi, N. Predictive value of vascular endothelial growth factor and placenta growth factor for placenta accreta spectrum. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 42, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakaza, A.; Liu, X.; Zhu, J.; Zou, L. Assessment of serum levels and placental bed tissue expression of IGF-1, bFGF, and PLGF in patients with placenta previa complicated with placenta accreta spectrum disorders. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2024, 37, 2305264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ruan, F.; Shu, H.; Zhu, L.; Man, D. First trimester serum PAPP-A is associated with placenta accreta: a retrospective study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 303, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N.; Krantz, D.; Roman, A.; Fleischer, A.; Boulis, S.; Rochelson, B. Elevated first trimester PAPP-A is associated with increased risk of placenta accreta. Prenat. Diagn. 2013, 34, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, O.; Otigbah, C.; Nnochiri, A.; Sumithran, E.; Spencer, K. First trimester maternal serum biochemical markers of aneuploidy in pregnancies with abnormally invasive placentation. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 122, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyell, D.J.; Faucett, A.M.; Baer, R.J.; Blumenfeld, Y.J.; Druzin, M.L.; El-Sayed, Y.Y.; Shaw, G.M.; Currier, R.J.; Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L. Maternal serum markers, characteristics and morbidly adherent placenta in women with previa. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzhoyan, G.A.; Makukhina, T.B. Significance of the routine first-trimester antenatal screening program for aneuploidy in the assessment of the risk of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. jpme 2019, 48, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, A.; Sekizawa, A.; Ventura, W.; Koide, K.; Hori, K.; Okai, T.; Masashi, Y.; Furuya, K.; Mizumoto, Y. Increased Levels of Cell-Free Human Placental Lactogen mRNA at 28–32 Gestational Weeks in Plasma of Pregnant Women With Placenta Previa and Invasive Placenta. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 21, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Gao, G.; Ye, Y.; Peng, W.; Zhou, J. Human placental lactogen mRNA in maternal plasma play a role in prenatal diagnosis of abnormally invasive placenta: yes or no? Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019, 35, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shainker, S.A.; Dannheim, K.; Gerson, K.D.; Neo, D.; Zsengeller, Z.K.; Pernicone, E.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Hacker, M.R.; Hecht, J.L. Down-regulation of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 expression in invasive placentation. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 296, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, W.; Yamamoto, S.Y.; Thompson, K.S.; Bryant-Greenwood, G.D. Relaxin, Its Receptor (RXFP1), and Insulin-Like Peptide 4 Expression Through Gestation and in Placenta Accreta. Reprod. Sci. 2013, 20, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illsley, N.P.; DaSilva-Arnold, S.C.; Zamudio, S.; Alvarez, M.; Al-Khan, A. Trophoblast invasion: Lessons from abnormally invasive placenta (placenta accreta). Placenta 2020, 102, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Dang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lin, J.; Wei, H.; Xia, H.; Long, J.; Luo, C.; et al. The expression and biological function of chemokine CXCL12 and receptor CXCR4/CXCR7 in placenta accreta spectrum disorders. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 3167–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhao, L.; Yue, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Fu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Fu, F. The relationship between IGF1 and the expression spectrum of miRNA in the placenta of preeclampsia patients. Ginekol. Polska 2019, 90, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedone, E.; Marucci, L. Role of β-Catenin Activation Levels and Fluctuations in Controlling Cell Fate. Genes 2019, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Z.; Luo, J.; Chen, R.; Yan, J. Expression of β-catenin in human trophoblast and its role in placenta accreta and placenta previa. J. Int. Med Res. 2018, 47, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garcia, V.; Lea, G.; Lopez-Jimenez, P.; Okkenhaug, H.; Burton, G.J.; Moffett, A.; Turco, M.Y.; Hemberger, M. BAP1/ASXL complex modulation regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition during trophoblast differentiation and invasion. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.-B.; Nakashima, A.; Huber, W.J.; Davis, S.; Banerjee, S.; Huang, Z.; Saito, S.; Sadovsky, Y.; Sharma, S. Pyroptosis is a critical inflammatory pathway in the placenta from early onset preeclampsia and in human trophoblasts exposed to hypoxia and endoplasmic reticulum stressors. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hamid, A.M.; Mesbah, Y.; Soliman, M.; Firgany, A.-D.L. Dominance of pro-inflammatory cytokines over anti-inflammatory ones in placental bed of creta cases. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2023, 12, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S.; Amaral, P.P.; Carninci, P.; Carpenter, S.; Chang, H.Y.; Chen, L.-L.; Chen, R.; Dean, C.; Dinger, M.E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.J.; Peñailillo, R.; Sánchez, M.; Acuña-Gallardo, S.; Mönckeberg, M.; Ong, J.; Choolani, M.; Illanes, S.E.; Nardocci, G. The Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Trophoblast Regulation in Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Genes 2021, 12, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannampuzha, S.; Ravichandran, M.; Mukherjee, A.G.; Wanjari, U.R.; Renu, K.; Vellingiri, B.; Iyer, M.; Dey, A.; George, A.; Gopalakrishnan, A.V. The mechanism of action of non-coding RNAs in placental disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Hannon, G.J. MicroRNAs: Small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004, 5, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-S.; Su, J.-L.; Hung, M.-C. Dysregulation of MicroRNAs in cancer. J. Biomed. Sci. 2012, 19, 90–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liang, B.; Lin, J.; Kim, T.-K.; Yu, H.; Hang, H.; Wang, K. A Systematic Study of Dysregulated MicroRNA in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.; Shih, J.-C.; Lin, H.-H.; Hsiao, A.-C.; Su, Y.-T.; Chien, C.-L.; Kung, H.-N. Unveiling the role of microRNA-7 in linking TGF-β-Smad-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition with negative regulation of trophoblast invasion. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 6281–6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Sadovsky, Y. The function of miR-519d in cell migration, invasion, and proliferation suggests a role in early placentation. Placenta 2016, 48, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrieta-Coxca, J.M.; Barth, E.; Fuentes-Zacarias, P.; Gutiérrez-Samudio, R.N.; Groten, T.; Gellhaus, A.; Köninger, A.; Marz, M.; Markert, U.R.; Morales-Prieto, D.M. Identification of altered miRNAs and their targets in placenta accreta. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1021640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C.; Li, S.; Liu, W.; Cao, Q. Decreased AGGF1 facilitates the progression of placenta accreta spectrum via mediating the P53 signaling pathway under the regulation of miR-1296–5p. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 23, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fu, X.-Q.; Yang, F.; Chen, Z.-W.; Mo, G.-L.; Lao, D.-Y.; Li, M.-J. Research on the expression of MRNA-518b in the pathogenesis of placenta accreta. 2019, 23, 23–28.

- Gu, Y.; Meng, J.; Zuo, C.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Zhao, S.; Huang, T.; Wang, X.; Yan, J. Downregulation of MicroRNA-125a in Placenta Accreta Spectrum Disorders Contributes Antiapoptosis of Implantation Site Intermediate Trophoblasts by Targeting MCLI. Reprod. Sci. 2019, 26, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Bian, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Zuo, C.; Meng, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, S.; Ning, Y.; Cao, Y.; et al. Downregulation of miR-29a/b/c in placenta accreta inhibits apoptosis of implantation site intermediate trophoblast cells by targeting MCLPlacenta 2016, 48, 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Kim, V.N. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerwise, L.; Li, J.; Lu, L.; Men, Y.; Geng, T.; Buhimschi, C.S.; Buhimschi, I.A.; Bukowski, R.; Guller, S.; Paidas, M.; et al. H19 long noncoding RNA alters trophoblast cell migration and invasion by regulating TβR3 in placentae with fetal growth restriction. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 38398–38407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Ren, C.; Zhang, H.; Gao, L. Silencing of LncRNA SNHG6 protects trophoblast cells through regulating miR-101-3p/OTUD3 axis in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Histochem. J. 2022, 53, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Gao, Q.; Wang, H. LncRNA SNHG16 regulates trophoblast functions by the miR-218-5p/LASP1 axis. Histochem. J. 2021, 52, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Cheng, X.; Jia, R. Long Non-Coding RNA Uc.187 Is Upregulated in Preeclampsia and Modulates Proliferation, Apoptosis, and Invasion of HTR-8/SVneo Trophoblast Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, P.; Zhang, L.; Liao, J.; Wu, Y.; Wen, L.; Tong, C.; et al. Upregulated LncZBTB39 in pre-eclampsia and its effects on trophoblast invasion and migration via antagonizing the inhibition of miR-210 on THSD7A expression. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 248, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, W.; Qiu, X.; He, M.; Tang, X.; Zhong, M. Periostin promotes extensive neovascularization in placenta accreta spectrum disorders via Notch signaling. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2023, 36, 2264447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calì, G.; D'Antonio, F.; Forlani, F.; Timor-Tritsch, I.E.; Palacios-Jaraquemada, J.M. Ultrasound Detection of Bladder-Uterovaginal Anastomoses in Morbidly Adherent Placenta. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2016, 41, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wang, R.; Liu, S.; Yin, X.; Huo, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, J. YKL-40 promotes proliferation and invasion of HTR-8/SVneo cells by activating akt/MMP9 signalling in placenta accreta spectrum disorders. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 43, 2211681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Su, C.; Zhu, L.; Dong, F.; Shu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, F.; Man, D. Highly expressed FYN promotes the progression of placenta accreta by activating STAT3, p38, and JNK signaling pathways. Acta Histochem. 2023, 125, 151991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Liu, W.; Zhao, J.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Duan, Y.; Huo, Y. Overexpressed LAMC2 promotes trophoblast over-invasion through the PI3K/Akt/MMP2/9 pathway in placenta accreta spectrum. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 49, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Schimmelmann, M.; Wu, Y.; Reisch, B.; Faas, M.; Kimmig, R.; Winterhager, E.; Köninger, A.; Gellhaus, A. CCN3 Signaling Is Differently Regulated in Placental Diseases Preeclampsia and Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badary, D.M.; Elsaied, H.; Abdel-Fadeil, M.R.; Ali, M.K.; Abou-Taleb, H.; Iraqy, H.M. Possible Role of Netrin-1/Deleted in Colorectal Cancer/Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Placenta Accreta Spectrum: A Case-control Study. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, K.; Miyagawa, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Takasaki, K.; Nishizawa, M.; Yatsuki, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Kamata, H.; Kihira, C.; Hiraike, H.; et al. The TGF-β/UCHL5/Smad2 Axis Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Placenta Accreta. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Weng, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Zheng, L. Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis, and induces ferroptosis of extravillous trophoblasts by targeting Wnt-β-catenin/VEGF signaling in placenta accreta spectrum. Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarker | Source | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-fetoprotein(AFP) | Maternal serum | APF showed a sensitivity and specificity of 71 and 46%, respectively to serve as a biomarker for pathological placentation, specifically in women with placenta previa and acreta in the second trimester. Thus, a high level of AFP can be used as suspicion in high-risk pathological placentation. | [22] |

| Maternal serum AFP levels were associated with PAS patients. Nonetheless, was establishedAs a predictor for PAS patients that require hysterectomy with 85.94% sensitivity and 71.43% specificity. | [23] | ||

| Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1(sFlt-1) | Maternal serum | Third-trimester sFlt-1 serum levels are decreased in those PAS-affected women, respectively with its pathological severity. | [24] |

| Maternal plasma | Concentrations of sFlt-1 were lower in patients with PAS than those with normal placentation, with 90.0% sensitivity and 82.0 % specificity. The lower concentrations were also associated with intraoperative blood loss. | [25] | |

| β human chorionic gonadotrophin(β-hCG) | Maternal plasma or serum | The elevated concentration of β-HCG in serum may be appropriate to the prenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta, which suggests the relationship between the risk of PAS in the first trimester. | [26] |

| Maternal serum | hCG showed a sensitivity and specificity of 53 and 68%, respectively, to serve as a biomarker for pathological placentation. Higher levels of hCG can be used as suspicion in high-risk pathological placentation. | [22] | |

| Maternal plasmacell-free β-hCG mRNA | Cell-free β-hCG mRNA concentrations were significantly elevated in women with placenta accreta. This suggests that β-hCG mRNA levels might be a marker for identifying women with placenta accreta likely to require hysterectomy. | [27] | |

| Placental growth factor(PlGF) | Maternal plasma | Concentrations of PLGF were higher in patients with PAS than those with normal placentation, with 86.0% sensitivity and 93.0 % specificity. Higher concentrations were also associated with intraoperative bleeding. | [25] |

| Maternal serum | PIGF serum levels are higher in PAS severity groups than normal placentation patients, including, placenta previa patients. Suggesting it as a predictor criterion exclusive for PAS patients with an 83% sensitivity and 82% specificity. | [28] | |

| Maternal serum and placental bed tissues | High serum levels and high placental bed expression in placenta previa patients with PAS disorders. PlGF serum levels might predict PAS affection, excepting the severity grade based on FIGO. | [29] | |

| Pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) | Maternal serum | Increased first-trimester serum was positively associated with placenta accreta, suggesting the potential role of PAPP-A as a biomarker in identifying pregnancies at high risk for placenta accreta. | [26,30-33] |

| A significant correlation was found between PAPP-A levels and blood loss volume. This suggests that first-trimester PAPP-A levels may be thoughtful for the early prediction of pathological blood loss at delivery in pregnant women with PAS and for recognizing a high-risk group for PAS. | [34] | ||

| Human placental lactogen mRNA(hPL mRNA) | Maternal plasma | The expression of hPL mRNA is elevated in the plasma of women diagnosed with placenta previa and invasive placenta between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation. | [35] |

| The multiple of the median (MoM) for hPL mRNA was significantly higher in the placenta accreta group compared to the control and placenta previa groups. | [36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).