Introduction

Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is a rare but severe idiosyncratic hypersensitivity reaction that can lead to multiorgan dysfunction and carries a mortality rate of up to 10% [

1]. Clinically, DRESS is characterized by fever, a widespread skin eruption, hematologic abnormalities such as eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, and systemic involvement—most commonly affecting the liver, kidneys, and lungs [

2]. The syndrome typically develops 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to the offending drug, with symptoms that may persist or worsen even after the drug is withdrawn, making early recognition and prompt intervention critical for patient outcomes [

3,

4]. The pathogenesis of DRESS is thought to involve a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, drug metabolism abnormalities, viral reactivations (notably HHV-6), and immune dysregulation [

5].

Among the drugs commonly associated with DRESS, vancomycin has increasingly been implicated, particularly in hospitalized patients receiving treatment for serious gram-positive infections, including methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) and

Staphylococcus aureus [

6]. Vancomycin remains a cornerstone in the management of prosthetic joint infections, especially in patients with prior hardware complications or multidrug-resistant organisms. However, its use is not without risk. Vancomycin-induced DRESS is a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, especially in the setting of orthopedic infections where prolonged antibiotic therapy is often necessary [

7].

In the postoperative period following joint replacement surgery, differentiating drug-induced hypersensitivity from surgical site infection, sepsis, or other causes of systemic inflammation can be particularly difficult. This is compounded in elderly patients, who often have multiple comorbidities and atypical clinical presentations. Effective management of DRESS requires immediate cessation of the suspected drug, careful evaluation for internal organ involvement, and in some cases, initiation of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment must also consider the ongoing need for infection control, especially in patients with incomplete antibiotic courses [

8].

In this case, we report a 70-year-old female with a complex clinical course following total hip arthroplasty complicated by prosthetic joint infection and subsequent vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome. The case illustrates the importance of early clinical suspicion, individualized antimicrobial stewardship, and multidisciplinary coordination in managing concurrent surgical and immunologic complications.

Case Presentation

The patient, a 70-year-old female with a significant medical history including hypertension, hypothyroidism, chronic back pain, and a left hip prosthetic joint infection, underwent total left hip replacement surgery in 2023 at an external hospital. The procedure was complicated by multiple revisions in January and February 2024. Following the final revision in February, which the patient tolerated well, she was discharged to a rehabilitation facility. The next day, she developed bleeding at the surgical site. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the pelvis without contrast revealed dislocation of the femoral head component extending superiorly into the pelvis beyond the iliac crest, prompting transfer to our hospital.

Upon arrival, a CT scan of the hip without contrast confirmed a failed left total hip arthroplasty with prosthetic hip dislocation and intrapelvic migration of the femoral component. Additionally, periprosthetic fractures of the left superior pubic ramus/pubic root and inferior pubic ramus were noted, along with a large left hip effusion extending into the subcutaneous tissue. The patient underwent complex revision surgery of the left total hip arthroplasty, involving proximal femur resection for osteomyelitis, drainage of a sinus, extensive irrigation, and debridement, followed by placement of an antibiotic spacer. Cultures from the surgery were positive for methicillin-resistant Streptococcus epidermidis (MRSE). Postoperatively, she began a six-week course of intravenous vancomycin twice daily, expected to complete in April 2024, in preparation for a two-stage hip revision after infection clearance.

Initially, the patient tolerated treatment well. However, in the fifth week, she developed a diffuse erythematous pruritic rash on her abdomen, (Image 1) which rapidly spread throughout her body. (Image 2) This led to her admission to the emergency department two days later. On evaluation, she reported chills but denied respiratory distress, facial swelling, chest pain, or other symptoms. She was afebrile and hemodynamically stable, with a diffuse maculopapular rash sparing the palms and soles. Initial labs showed an elevated white blood cell count of 15.31 k/uL, with an absolute neutrophil count of 11.65 k/uL and an absolute eosinophil count of 1.49 k/uL. Vancomycin was discontinued, and the infectious disease team was consulted regarding ongoing antibiotic therapy for the prosthetic joint infection. The patient expressed discomfort with the peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, prompting a switch to oral linezolid 600 mg twice daily for the remainder of her antibiotic course.

A diagnosis of vancomycin-induced hypersensitivity reaction, consistent with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), was considered. The European Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reaction Criteria (RegiSCAR) was used and the patient received two RegiSCAR points negative tests for ANA, blood culture, and hepatitis and normal renal function tests. This score classified the risk of vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome as "Possible case.

The reaction was classified as mild due to the absence of end-organ damage, with kidney and liver function tests showing blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels of 15-21 mg/dL, creatinine (Cr) levels of 0.85-0.93 mg/dL, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of 15-20 U/L, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels of 14-18 U/L. Systemic steroids were initially deemed unnecessary; however, as the rash became more erythematous and "beefy," systemic corticosteroids were initiated with a single dose of intravenous methylprednisolone 80 mg, resulting in symptom improvement.

Dermatology was consulted for a skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of DRESS prior to discharge, though it was not performed at that time. The patient was advised to follow up outpatient for thyroid function monitoring, given the risk of hypothyroidism developing four to twelve weeks post-DRESS reaction. Due to the short course of steroids, no taper was required. With significant symptom improvement and transition to oral antibiotics, the patient was discharged home.

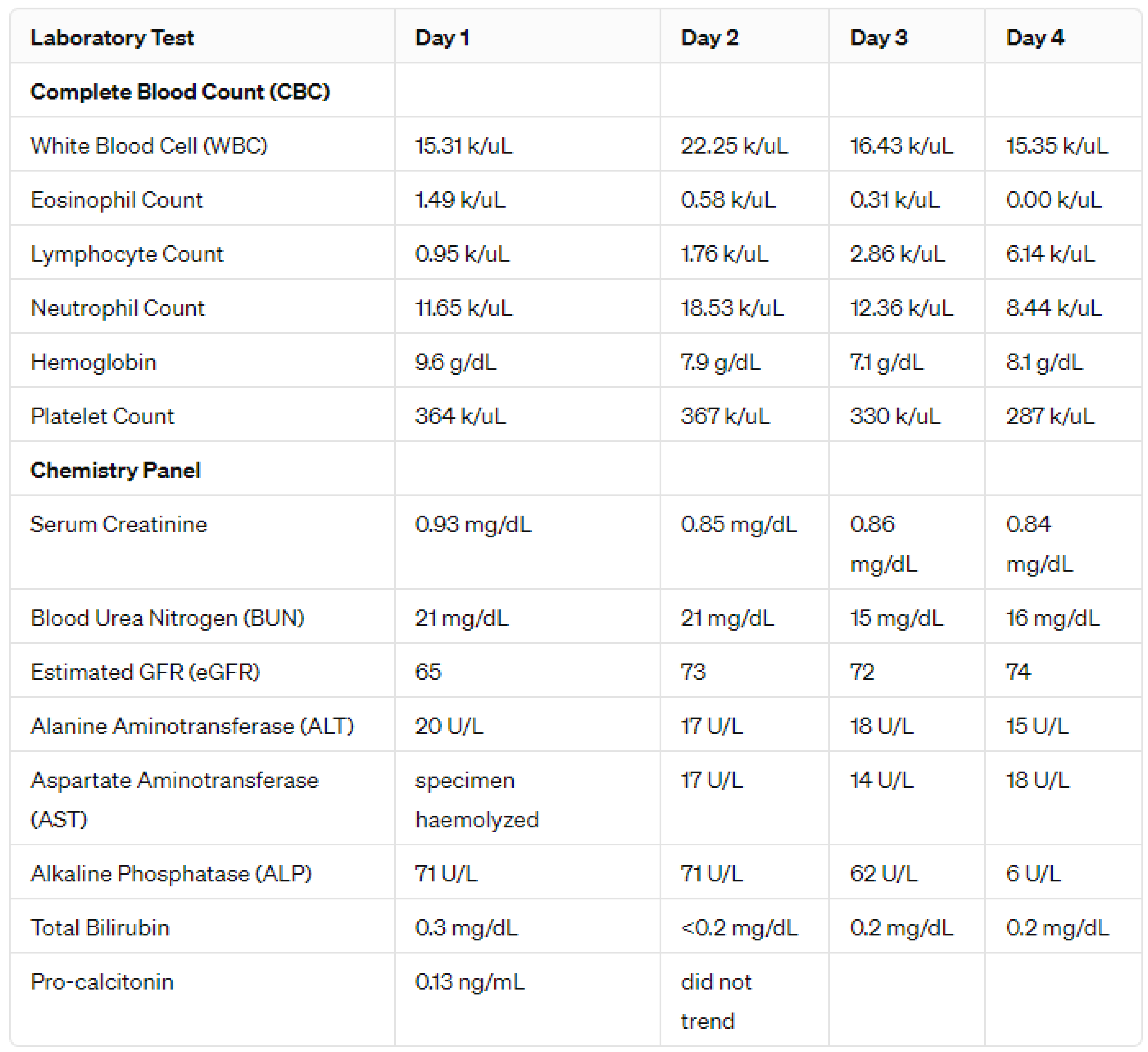

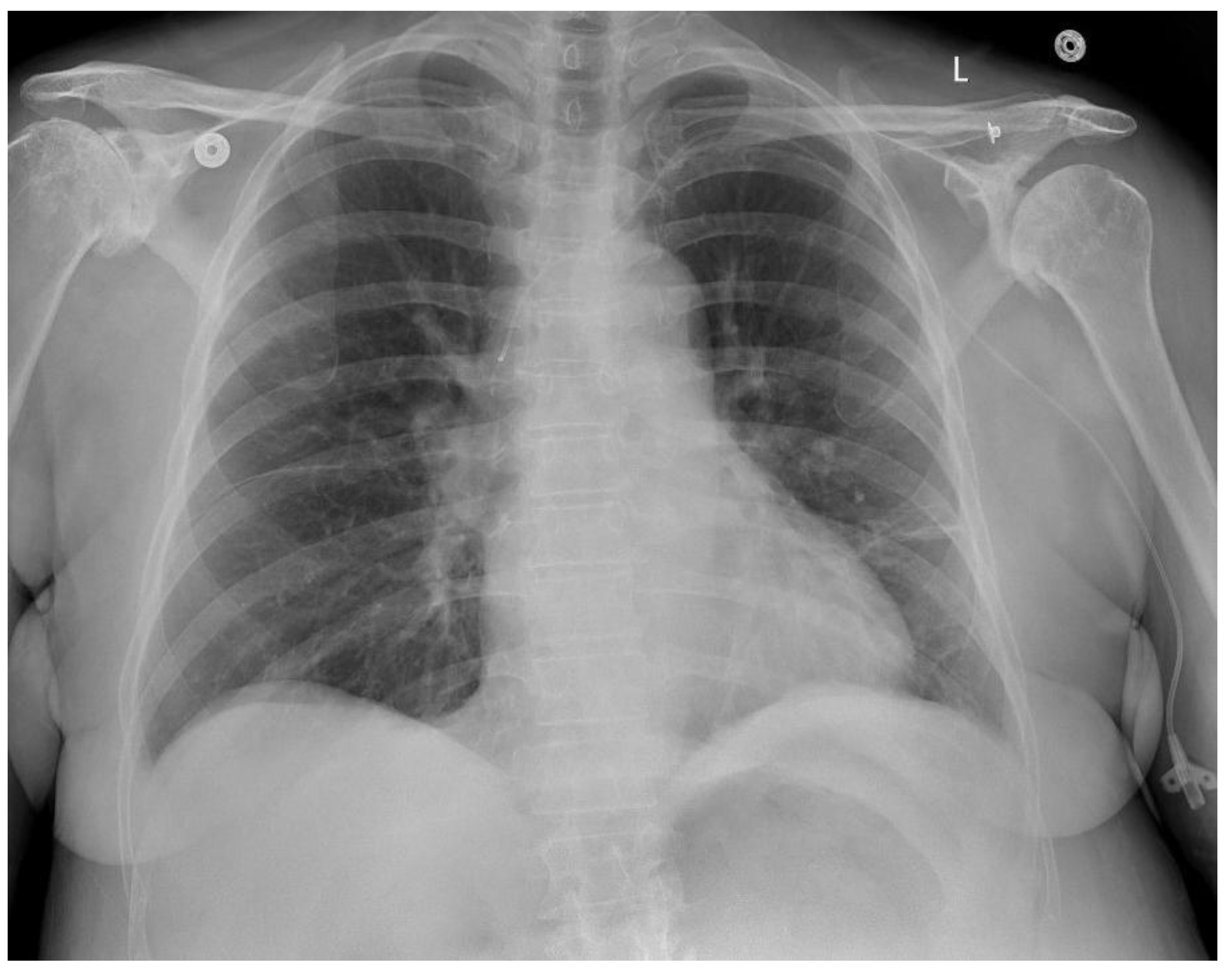

Investigations and Imaging

During hospitalization, laboratory and imaging studies played a key role in evaluating suspected vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome. Blood tests showed dynamic changes in white blood cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and neutrophils, supporting an evolving hypersensitivity reaction. Mild liver involvement was noted, while renal function remained stable. Imaging was limited to a chest X-ray, which ruled out acute cardiopulmonary issues but noted chronic musculoskeletal changes and borderline cardiac enlargement. The absence of a skin biopsy and broader diagnostic tests limited definitive confirmation. Overall, investigations were crucial for monitoring organ function and guiding treatment, despite certain diagnostic limitations.

Treatment and Follow-Up

The cornerstone of DRESS syndrome management is prompt discontinuation of the offending agent. In this case, vancomycin was immediately discontinued upon the patient’s admission. Given that the patient had only completed five weeks of a planned six-week course of intravenous antibiotics for prosthetic joint infection, the next critical decision was selecting an alternative antibiotic to ensure continued infection control in preparation for her planned two-stage hip replacement.

Linezolid 600 mg twice daily was initiated as a suitable oral alternative due to its comparable antimicrobial coverage, particularly against gram-positive organisms including MRSE. The choice also aligned with the patient’s preference to avoid further use of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line, which she found uncomfortable. The duration of linezolid therapy was planned to coincide with the originally intended completion date of the vancomycin regimen.

Although systemic corticosteroids are generally not indicated for mild DRESS without visceral organ involvement, the patient’s clinical course warranted reconsideration. Over the course of hospitalization, her rash became increasingly erythematous and extensive, eventually involving her face and significantly impacting her comfort. In response, an intramuscular dose of 125 mg methylprednisolone was administered, followed by an 80 mg dose the next day. This short course of systemic corticosteroids resulted in notable symptomatic relief. As the treatment duration was brief and the patient's symptoms improved substantially, a steroid taper was deemed unnecessary at discharge.

Follow-Up Plan

The patient was discharged with continued oral linezolid therapy and advised to closely monitor for any recurrence of symptoms. She was instructed to follow up with dermatology and infectious disease in the outpatient setting. Given the known association between DRESS syndrome and the later development of autoimmune sequelae such as hypothyroidism, she was also advised to undergo thyroid function testing within 4 to 12 weeks post-discharge. Further follow-up will be necessary to monitor for delayed complications, evaluate readiness for the second-stage hip revision, and assess long-term outcomes of the hypersensitivity reaction.

Discussion

This case highlights several critical considerations at the intersection of orthopedic infection management and drug hypersensitivity. Vancomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic widely used to treat methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) in prosthetic joint infections (PJI), has occasionally been implicated in drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome—an uncommon but potentially life-threatening adverse effect.[

9] The latency period of 2–9 weeks between vancomycin initiation and symptom onset in this patient aligns with the median onset of vancomycin-induced DRESS reported in recent systematic reviews .[

10]

Early recognition and prompt discontinuation of vancomycin remain the most effective interventions to prevent organ failure in DRESS syndrome.[

11,

12] In our patient, vancomycin withdrawal led to stabilization of renal and hepatic biomarkers, underscoring the value of vigilant monitoring. However, differentiating DRESS from ongoing prosthetic infection or sepsis can be challenging in postoperative orthopedic patients. Reports of vancomycin-induced DRESS in arthroplasty contexts emphasize confusion with infection or treatment failure, often resulting in delayed diagnosis.

Choosing an alternative antibiotic posed both a therapeutic and practical dilemma. Linezolid, at 600 mg twice daily, provided comparable coverage against gram-positive bacteria—including MRSE—and offered high oral bioavailability, making it a suitable choice for outpatient continuation without the discomfort of a PICC line.[

13] Linezolid is increasingly used in PJI management, with studies demonstrating equivalent efficacy to daptomycin and good clinical outcomes following surgical debridement[

14] Despite its benefits, awareness of linezolid’s hematologic and neurologic adverse effects—especially during prolonged therapy—is crucial.[

15]

The dynamic nature of cutaneous rash evolution in this patient—from pruritic erythema to confluent "beefy" plaques—coincided with systemic inflammation, fulfilling RegiSCAR criteria for DRESS.[

10] Although initial presentation lacked end-organ damage, glucocorticoid therapy was indicated as symptoms worsened. Short-term intramuscular methylprednisolone provided rapid relief, consistent with current recommendations that reserve systemic corticosteroids for moderate to severe DRESS.[

9] The absence of a taper was consistent with the brief steroid course and lack of relapse.

This case underscores the importance of multidisciplinary coordination between orthopedics, infectious disease, and dermatology. A high index of suspicion for immune-mediated drug reactions is essential in PJI, where prolonged antibiotic use may predispose to severe adverse events. A systematic review of prosthetic joint surgery cases similarly concluded that DRESS—though rare—should be considered early to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary antibiotic escalation.[

10]

Moreover, this case emphasizes the need for vigilant post-discharge follow-up. DRESS carries a risk of delayed autoimmune sequelae, including thyroid dysfunction, underscoring the need for targeted outpatient surveillance. Coordinated timing of the two-stage hip revision should also consider both infection control and resolution of hypersensitivity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this case illustrates the diagnostic complexity and therapeutic balancing required in managing vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome amidst ongoing treatment for a prosthetic joint infection. Timely identification of the drug reaction, prompt switch to an effective oral alternative (linezolid), judicious use of corticosteroids, and seamless interdisciplinary coordination were key to the patient’s recovery. This case underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for drug hypersensitivity reactions in patients receiving prolonged antibiotic therapy, particularly in the postoperative setting, and highlights an effective framework for managing similar challenges in orthopedic infections.

References

- Shiohara, T.; Kano, Y. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): incidence, pathogenesis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017, 16, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, Z.; Reddy, B.Y.; Schwartz, R.A. DRESS syndrome: Part I. Clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013, 68, e1–e708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacoub, P.; Musette, P.; Descamps, V.; et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011, 124, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.T.; Yang, C.W.; Chu, C.Y. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS): An Interplay among Drugs, Viruses, and Immune System. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18, 1243, Published 2017 Jun 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardaun, S.H.; Sekula, P.; Valeyrie-Allanore, L.; et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013, 169, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischman, A.N.; Austin, M.S. Local Intra-wound Administration of Powdered Antibiotics in Orthopaedic Surgery. J Bone Jt Infect. 2017, 2, 23–28, Published 2017 Jan 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chiu, H.C.; Chu, C.Y. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010, 146, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, Y.; Inaoka, M.; Shiohara, T. Association between anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome and human herpesvirus 6 reactivation and hypogammaglobulinemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004, 140, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhumireddy, S.K.A.; Gudla, S.S.; Vadaga, A.K.; Nandula, M.S. Vancomycin-Induced DRESS Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Hosp Pharm. Published online May 23, 2025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, K.P.; Alsoud, F.; Prashad, A.; et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an unusual manifestation of multi-visceral abnormalities and long-term outcome. Discoveries (Craiova). 2023, 11, e170, Published 2023 Aug 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, O.; Hassanein, M.; Armstrong, J.; Kassis, N. Case report: atypical presentation of vancomycin induced DRESS syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Pulm Med. 2017, 17, 217, Published 2017 Dec 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güner, M.D.; Tuncbilek, S.; Akan, B.; Caliskan-Kartal, A. Two cases with HSS/DRESS syndrome developing after prosthetic joint surgery: does vancomycin-laden bone cement play a role in this syndrome? BMJ Case Rep 2015, 2015, bcr2014207028, Published 2015 May 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theil, C.; Schmidt-Braekling, T.; Gosheger, G.; et al. Clinical use of linezolid in periprosthetic joint infections - a systematic review. J Bone Jt Infect. 2020, 6, 7–16, Published 2020 Jul 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada, M.; Oe, K.; Hirata, M.; et al. Linezolid versus daptomycin treatment for periprosthetic joint infections: a retrospective cohort study. J Orthop Surg Res 2019, 14, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morata, L.; Senneville, E.; Bernard, L.; et al. A Retrospective Review of the Clinical Experience of Linezolid with or Without Rifampicin in Prosthetic Joint Infections Treated with Debridement and Implant Retention. Infect Dis Ther. 2014, 3, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).