1. Introduction

It is widely recognized that some women suffer ongoing emotional distress following an elective abortion.[

1,

2] How many women do so, and for how long a time, are facts related to vigorously contested questions, such as whether the distress is related to the abortion itself, the pregnancy that prompted the abortion, or other factors; whether distress following an abortion is greater or less than distress following childbirth; and the role of pregnancy intention. Today the prevalence and duration of post-abortion distress (PAD) is disputed and unclear. While generally agreeing on the presence of PAD shortly after the abortion, study results diverge from there, with some finding that by six months to five years following the abortion PAD declined to parity with non-aborting women,[

3,

4,

5] on the one hand, and others that PAD persisted and even increased over similar time periods,[

6,

7,

8,

9] on the other hand.

While the extent and causes are debated, almost all assessments of post-abortion psychological risk have discovered that some women experience emotional distress, even strong emotional distress, following an abortion. In 1989 the U.S. surgeon general stated that “psychological problems from abortion are rare and not significant from a public health viewpoint,” but also that “abortion can cause long-term psychological problems for some women” and “there is no doubt that there are people who have a post-abortion syndrome.” [

10] Successive reviews in 1989 and 2008 of the abortion and mental health literature by the American Psychological Association, while concluding that abortion was no more prone than childbirth to systematic mental health problems “recognized that some individual women experience severe distress or psychopathology following abortion.” [

1]

A series of studies based on a sample of 667 patients drawn from about 30 U.S. abortion clinics in 2008-2010 have extensively reported the emotional characteristics of women interviewed one week following their abortions. At that time, 29% expressed substantial negative emotions, either with (12%) or without (17%) accompanying positive emotions.[

5] While 92% expressed relief and 95% felt the abortion had been the right decision, 59% also expressed guilt, 38% regret, and 29% anger, specifically about the abortion. The share expressing sadness (65%) about the abortion was greater than the proportion expressing happiness (55%). [

11] A total of 21.0 % had indications of depression, and 15.4 % had indications of anxiety disorder. [

3] As measured by the Primary Care PTSD Screen, 39% reported post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) one week after the abortion, with 16% reporting 3 or more symptoms, an indication of risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). [

12] While citing a variety of causes for their PTSS, the study noted that “[a]mong those who attributed their symptoms to the index pregnancy experience (n=64), many (n=19) succinctly stated that ‘the abortion’ was the source of their symptoms.” [

12] In fact, according to the reported results, 64% of aborting women who attributed their PTS symptoms to the index pregnancy further specified that they were due to the abortion (

Table 2, p. 6).

1 The disparate findings of these studies, a mixture of both positive and negative emotional responses, supported the observation that “each woman’s experience is unique and … women will vary in their responses to having an abortion … .” [

4]

The related studies cited in the previous paragraph all claimed that almost all measures of PAD declined to parity with non-aborting women up to five years following the abortion. A variety of other studies, however, have found persisting or increased levels of distress over similar follow-up times after the abortion. Major et al.’s study of a similar sample of abortion clinic patients over two years noted that “negative emotions increased and decision satisfaction decreased over time.” [

7] Likewise, Rees and Sabia found that depressive symptoms in new mothers rose from 21.0% to 31.6% up to two years following an abortion. [

8] Similar to Biggs et al.’s [

11] finding at one week postabortion, at one month following the abortion Sit et al. [

13] found that 17-21% of women were at high depression risk. Pereira et al. [

14] found that, two to three weeks after the abortion, a majority of both adolescent and adult women scored above the cutoff for depressive symptoms on the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in a sample of Portuguese abortion patients. Major et al.’s [

7] survey of 442 U.S. women randomly sampled from abortion patients found that 2 years after the abortion 20% were depressed; 28% were not satisfied with their decision; 19% said they would not have an abortion again in similar circumstances; and 28% did not report more benefit than harm from their abortion (p. 777). The proportion of women who felt they had made the wrong decision rose from 11% one month after the procedure to 16% at two years after the procedure (p. 779). Warren et al., using an unusually high cutoff score for the 9-item CES-D (11 as opposed to the more usual 8 or 9) that understated the rate of depression relative to other studies, reported that 14.1% of teenage women were depressed at about one year following the abortion, rising to 16.1% about five years postabortion. [

15]

Two studies using non-U.S. samples have reported declines in some measures of distress over time after an abortion. Söderberg et al., from interviews with 854 Swedish women, reported that high levels of depression immediately after the abortion declined over time, but still remained high, finding that after one year “50–60% of women undergoing induced abortion experienced some measure of emotional distress, classified as severe in 30% of cases.” [

16] Likewise, Broen et al. reported a decline from high postabortion anxiety over time in a hospital sample of 120 Norwegian women, but after five years 34.3% of women still met the criteria for anxiety and 11.2% for depression. Both of these studies reported terminal rates of distress substantially higher than in the studies reporting a decline cited above. Although the evidence is mixed, most studies that included measures of distress have found that some measures persisted, and some increased, over time up to five years following an abortion.

All these studies reported roughly similar rates of depression, at about 20%, assessed at from one week to two years after the abortion. Lack of confidence in the abortion decision increased with longer time periods, from 5% at one week postabortion [

11] to 20% at one year [

16] to 28% at two years. [

7] Broen et al. also found that doubt about the decision to abort and a negative attitude toward abortion were related to depression and anxiety up to five years following the abortion. [

6]

Studies that have examined much longer follow-up of at least ten years or more have all found substantial or persisting distress following an abortion. [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Analyzing 467 cases up to a decade after the abortion on the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Schmiege and Russo [

19] reported that 24.9% of women aborting an unwanted first pregnancy were at high risk for depression. The percentage was higher for those reporting ten or more years following the abortion (26.2%) than for those reporting at four or fewer years postabortion (23.7%), though this difference is not statistically significant in these data. [

19] Steinberg and Finer, reporting lifetime retrospective pregnancy data for 293 women, found that the proportion of women with symptoms consistent with three or more psychiatric disorders rose from 27.3% to 34.6% following an abortion. The most common disorder was anxiety, which rose from 39.3% to 46.4%. The point of the study was that the rate of increase in disorders was no different for women following abortion than for women giving birth, who had overall lower prevalences of disorders. Follow-up time since the abortion varied, but averaged 10-12 years. [

20]

Three sets of longitudinal studies with similar designs followed cohorts of women up to thirteen years, from adolescence into their late 20s. All three studies found significant increases after abortion in the risk of psychological disorders, including depression, anxiety, suicide ideation, alcohol abuse, marijuana abuse, and other illicit drug abuse. [

17,

18,

21,

22,

23,

24] Fergusson et al. noted that such findings were consistent with evidence that “for a minority of women, abortion is a highly stressful life event which evokes distress, guilt and other negative feelings that may last for many years.” [

17]

The present study aims to address the question of declining or persistent PAD through an examination of population-representative retrospective data of women at the end of their childbearing years. The average look-back time since the abortion was 20.3 years (weighted; 95% CI 19.4, 21.2), with a range of 0 to 31 years, a period which is longer than almost any previous study. Although it is hard to predict clearly, the most moderate expectation is that the extent of PAD this distal from the abortion will be similar to that in studies finding persistence, that is, neither increase nor decline from the initial level, at five years postabortion. This sense is expressed in the following hypotheses:

At completed fertility:

H1) PAD prevalence will neither have diminished into insignificance nor increased greatly but will be similar in prevalence to that measured in most studies up to five years following the abortion.

H2) Most women will report little or no distress regarding their abortion.

H3) A large majority of women will continue to affirm that having an abortion was the right decision for them.

2. Materials and Methods

Data for the present study were derived from an online survey administered in 2022 to a sample drawn from members of the Cint panel (

www.cint.com). Cint is a Swedish digital research technology firm that aggregates sample sources from over 350 suppliers to create a blended sampling frame that is representative of a specific population of interest. The full aggregate panel includes 335 million participants for survey research, 28 million of whom reside in the United States. The data collection was commissioned by the Charlotte Lozier Institute, a pro-life leaning research institute, for use in two previous studies of women’s experience of abortion. [

25,

26] The collection and the characteristics of the data are described in further detail in those studies. The archived data are now publicly available for secondary analysis. [

27]

The criteria for participation in the survey for the present study were United States residence, female, and ages 41-45. Opt-in participation replicated random selection, with further screening and stratification to ensure optimal data quality and population representation. Extensive measures were taken to prevent opt-in bias, multiple participation, and inattentive or fraudulent response patterns. The result was a sample of 1,000 participants which represented, as much as possible, the population of U.S. women aged 41-45 years in 2022. The analytic sample for the present study consisted of 226 respondents (22.6%, 95% CI 20-26) who reported lifetime abortion exposure.

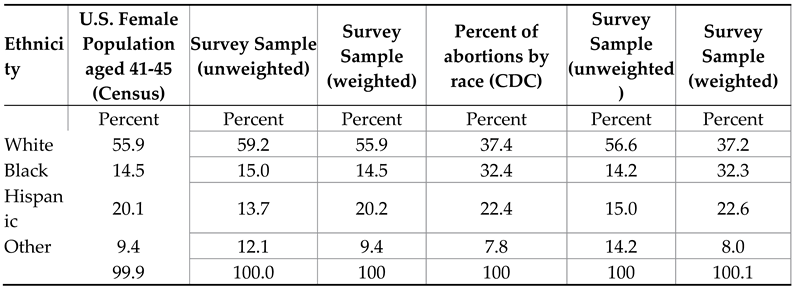

The survey, which was in English, undersampled Hispanics. Reported abortions were also biased by race/ethnicity, with black and Hispanic respondents reporting fewer abortions, and respondents of other race/ethnicity categories reporting more abortions, than was true for such groups in the population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. [

28] Post-stratification weights were applied to the data to rectify these discrepancies and support population estimates. The resulting distribution closely matches the actual population of U.S. women and ever-aborting women aged 41-45. The comparative distributions are reported in

Table 1.

A detailed description of all the variables in the data, with univariate statistics, has been published. [

26] For brevity, this section addresses only constructed variables unique to the present study.

Most survey items were of a similar form, consisting of indicative statements above a line with two response extremes, such as “Not at all true” to “Very true,” or “None at all” to “Very high.” Respondents’ opinions were reported using a moveable onscreen slider between the two response extremes. The survey software transformed the visual distance from the low extreme into a number representing the percentage of the total distance between the two extremes, effectively scoring the results on a continuous scale from 0 (Not at all true, etc.) to 100 (Very true, etc.), with 50 indicating placement midway between the extremes.

Four statements asked respondents who had ever had an abortion to indicate their agreement or disagreement about their emotions related to their abortion(s). The statements, and their corresponding extremes, were: My negative emotions regarding the abortion are … [None at all; Very high]; I have had frequent feelings of loss, grief, or sadness about the abortion [Not at all true; Very true]; I have had frequent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks to the abortion [Not at all true; Very true]; and, Thoughts and feelings about my abortion have negatively interfered with daily life, work, or relationships [Not at all true; Very true]. There was a very high level of agreement among the responses for these seven items. Alpha was .88. These items were combined into a single additive scale of post-abortion emotional distress (PAD) ranging (after recalibration) from 0 to 100. Respondents with scale scores from 0-40, 41-60, and 61-100 were respectively classified as expressing little or no emotional distress, medium distress, and high distress.

The focus of the analysis was on estimating the prevalence of PAD and related measures under various population and demographic conditions. After weighting to adjust sample bias to known ever-aborting population parameters, population-adjusted proportions of PAD and decision rightness were estimated using the additive scale already described, and compared with the general consensus of prior research to evaluate the study hypotheses. Demographic distributions and population estimates were then derived by applying weighted percentages to U.S. Census counts and estimates of the pertinent subpopulations of women by year and age.

Procedures involving human subjects were approved by Sterling Institutional Review Board (IRB), Approval ID 10225. Broad informed consent was obtained or waived by all participants in the original data collection. The present study engages solely in secondary analysis of this publicly available de-identified data, a use which has been determined by the United States Office of Human Protection of the Department of Health and Human Services to be exempt from further human subject ethical review under 45 CFR 46.104 (2018 revision). All analyses were performed using Stata 18 and 2024 versions of MedCalc and/or Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 2 reports demographic characteristics of the sample by abortion experience. The demographic distribution of the sample generally matched that of the underlying population. The 2022 median income for all female workers was

$52,360;[

29] the median income category in our sample was

$50,000-

$74,999. The regional population distribution reported by the US Census in 2021 (the latest available data), followed by the proportion shown in

Table 2 in parentheses, was: Midwest, 20.7% (20.4%); Northeast, 17.2% (14.8%); South, 38.3% (43.4%); West, 23.7% (21.3%). Female educational attainment, with Census proportion followed by that of our sample in parentheses, was: High school diploma or less, 34.8% (37.3%); University degree, 35.5% (44.9%); Postgraduate education 15.0% (17.8%). [

30] The Census also reported that 14.8% of women aged 25 years and older had some college education, but no degree. This category was not included on the survey questionnaire; these women likely indicated either high school diploma or university degree (particularly if they had received some sort of program certification for their university work, since the questionnaire did not specify the type of “degree”), which would reasonably correspond to the overages in these survey categories relative to the Census. As already noted, the sample distribution of race/ethnicity precisely matched that of the U.S. population due to weighting.

Compared to those not exposed to abortion, postabortive women tended to have somewhat lower income and education, nonwhite race/ethnicity, and to live outside the Midwest. Black women were much more likely than those of other race/ethnic groups to have had an abortion (as determined by sample weights).

3.2. Postabortion Distress

Table 3 presents 4 measures of negative feelings and experiences related to having had an abortion, in descending order of mean negativity. The percentage frequencies shown include only women who reported having one or more abortions (n = 226), and the items specifically indicated only feelings related to the abortion. The items report the respondent’s choice between two extremes, coded from 0 (low extreme) to 100 (high extreme). If a score greater than 60 is interpreted as net agreement with the high extreme, then 38% of post-abortive women agreed that their negative emotions were very high; 31% that they have had frequent feelings of loss, grief and sadness about the abortion; 25% that they have had frequent thoughts, dreams or flashbacks to the abortion; and 23% that thoughts and feelings about the abortion have negatively interfered with daily life, work or relationships. Respondents with this rating level (61-100) were classified as highly distressed related to their abortion on each of these measures.

Almost half of the post-abortive women (47.9%) indicated high abortion-related distress on at least one of the four measures, although a large majority (75.5%) indicated low distress by the same metric. Only 11.0% of respondents indicated high distress, and 24.5% a lack of distress, on all four measures. The additive scale of PAD, which essentially averages the four measures, classified just under a quarter (24.1%) of respondents as highly distressed (combined response of 61% or higher), just over half (55.2%) with little or no distress (40% or lower), with the remaining fifth (20.7%) as neutral (41-60%).

Table 4 reports the proportion of ever-aborting women with high PAD by demographic characteristics. The percentage differences are only suggestive due to the small number of cases in each demographic category, as reflected in the large confidence intervals. The differences suggeste that ever-aborting women of a minority race or ethnicity other than White, Black, Hispanic or Asian; with a postgraduate education; or who lived in the Northeast may have been more prone to PAD. Asian women or those whose highest educational attainment was a university degree may have been less prone to PAD.

3.3. Post-Traumatic Stress

The PAD scale items corresponded to diagnostic criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress (PTS), formerly Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), in the APA’s 2022 revised DSM-5-TR. PTS symptoms noted in DSM-V included: “recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s);” “recurrent distressing dreams …related to the traumatic event(s);” “persistent negative emotional state (e.g., fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame);” “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” [

31] While a full PTS diagnosis entails other criteria which were not measured, including reactivity, duration of symptoms, or the absence of co-occurring medication, women with high PAD expressed, at minimum, high levels of subclinical trauma. Those who scored above 60 on all four PAD items conforming with PTS criteria may be considered candidates for PTS. As already noted, 11% of postabortive women met this condition, consisting of just under half (45.6%), of all women with high PAD (i.e., 11.0/24.1 in

Table 3). Almost half (48%) of all postabortive women scored high (60 or higher) on at least one PAD measure. Altogether, these results suggest a high level or component of trauma processing in post-abortion distress.

3.5. Population Estimates

The population-weighted proportion of first abortions obtained, in five year categories, were (with 95% confidence intervals): less than age 20, 37.4% (30.3-45.0); 20-24, 37.7% (30.4-45.5); 25-29, 10.8% (6.8-16.6); 30-34, 14.2% (10.0-19.8). No first abortions were reported at age 35 or older. The US Census reported 10,422,788 women aged 41-45 resident in the United States as of July 1, 2022.[

28], from which it can be estimated that 2,355,550 (22.6%) women of this cohort have experienced one or more abortions, of whom 567,688 experienced high PAD, with 259,110 of these expressing consistent diagnostic criteria for PTS.

If the distribution of first abortions by age is similar for other recent cohorts, these proportions can also estimate the number of postabortive women, and the number of women with high PAD and/or abortion-related PTS, in the U.S. population.

Table 5 presents the analysis. The cumulative percent of abortions column shows the summation of the percentages just noted by the oldest age of each age category. For example, 86.1% of first abortions were obtained by age 29, a summation of the categories less than 20, 20-24, and 25-29. Multiplying the median percentage for each period by the number of women in each cohort in 2022 results in the estimates shown the column “Postabortive women.” The upper age limit was set at 93, since women older than 93 would have been past childbearing age when abortion was nationally legalized in 1973, and thus much less likely to have been exposed to an abortion. Totals of 24.1% and 11.0% of this number estimates the number in the respective columns “Women with high PAD” and “Women with four or more PTS symptoms.” In sum, the analysis suggests that, of the 138.3 million women above childbearing age (age 15 or older) in the U.S. in 2022, about 31.3 million had had at least one abortion, 7.5 million experienced high PAD, and 3.4 million experienced at least four abortion-related symptoms of PTS.

4. Discussion

This study found that the prevalence of PAD decades after an abortion was similar to that generally observed in previous studies at much shorter times following the abortion. Just as repeatedly observed at two years or less postabortion, so at 20 years postabortion, on average, a large majority of ever-aborting women affirmed that the abortion had been the right decision and most (55%) did not experience significant negative emotions, but a substantial minority suffered moderate (21%) to high (24%) emotional distress attributable to their abortion(s).

4.1. Assessment of Hypotheses

Hypothesis H1 proposed that the prevalence of PAD, at an average of 20.3 years after the abortion in these data, would be similar to that in comparable studies finding persistence in PAD up to five years after the abortion. Due to high nonresponse in fertility surveys and cultural differences in samples of non-U.S. women, the most comparable studies are those which drew samples of U.S. obtaining abortions. As already noted, such studies found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms after the abortion was 21% at a week, [

3] 17-21% at a month, [

13] and 20% after two years. [

7] Negative emotions were at 29% a week after the abortion. [

11] While differences in measures preclude precise comparisons, it is clear that the 24.1% prevalence of average high PAD in the present study is not consistent with either sharply declining or sharply increasing PAD compared to these former findings, but rather is broadly similar to them. Likewise, in the present data 23% of ever-aborting women reported three or more symptoms of PTS (

Table 3), compared to 16% who did so at one week postabortion in an earlier study. [

32] Based on these comparisons, H1 is supported. Confirming this result, there was no significant correlation between PAD and time since the abortion (r was -.02, p=.71) in the present data.

Overall comparisons among studies cannot be more than approximate due to the different measures involved. Some questions, however, more closely replicated those in other studies, permitting more direct comparisons, which confirm the similarity of the present findings to those in previous studies with shorter follow-up. Biggs et al. 2016 reported that of women who had abortions, 38.9% reported at least one PTSS symptom, and 15.4% three or more PTSS symptoms, at one week after the abortion (

Table 1). The corresponding proportions (weighted) in the present data were 48.7% and 20.7%. This comparison is consistent with the well-documented fact PTSD is often subject to delayed onset. [

33,

34] Rocca (2013) reported that 65.3% of aborting women expressed at least some sadness about their abortion experience; in the present study 61.3% expressed anything more than a trivial amount of negative emotions (

Table 3). As reported above, Major (2000) reported that the proportion of women who felt they had made the wrong decision rose from 11% one month after the procedure to 16% at two years. The comparable proportion (derived by dichotomizing the continuous scale of decision rightness) in the present data is 18.2% who would likely respond “no” on a yes/no question of decision rightness.

Hypothesis H2 stated that most women will report little or no distress regarding their abortion. Whether or not these results support H2 as true depends on how one interprets the measurement of PAD.

Table 3 presents the alternatives. In this analysis a response of 40 or less on each distress measure, that is, toward the “not at all true” or “none at all” end of the response range, is interpreted as indicating little or no distress. By the strictest construct, indicating little or no distress on all four measures, only a little over a fourth (26.9%) of women reported little or no distress on all four measures, supporting H2. On the other hand, a majority of women (62.1%) indicated little or no distress on at least two of the four distress measures of distress, and average response over the four items was less than 50 (40.6), with over half (55.2%) indicating low distress, on average. In addition, less than half (47.9%) of women indicated high distress on at least one item, the most generous measure, and only a quarter (24.1%) indicated high average distress. On balance, these results support H2, in my determination. Other interpretations are possible, however, and the majority reporting little or no distress is not large.

H3 projected that at 20 years postabortion a large majority of women will continue to affirm that having an abortion was the right decision for them. This hypothesis is clearly supported. To the statement, “Given my situation, the decision to have an abortion was the right decision for me,” where zero indicated “Not at all true” and 100 indicated “Very true,” the mean response was 74.1 (95% CI 69.9, 78.4). Over a quarter of respondents (25.7%) moved the slider to the far right, indicating a response of 100. The response distribution for this item can be interpreted as three categories of “Confident it was the right decision” (67-100), “Doubtful it was the right decision” (0-33), and “Unsure” (34-66). On this classification, 70.1% (95% CI 63-77) of respondents (population-weighted) were confident it was the right decision; 8.8% (95% CI 5-14) doubtful it was the right decision; and 21.1% (95% CI 16-28) were unsure.

The three hypotheses tested the general premise that the prevalence of PAD at up to 30 years following the abortion was similar to that shortly after the abortion. The finding that all three hypotheses were supported suggests that this general premise is accurate, and that net PAD does not greatly diminish nor increase over longer periods following an abortion. About one in ten ever aborting respondents (11%) met four or more criteria for post-traumatic stress (PTS) related to their abortion(s). Although there may be offsetting transient trends, and individual women’s experience may vary, the net distribution of women’s average emotional response to abortion appears to be more or less permanent.

4.2. Other Research

These findings moderate between extreme claims that almost all women, or alternatively almost no women, suffer emotional distress following an abortion. Relative emotional distress may be overstated in studies that did not account for pre-existing distress or the independent effect of a problem pregnancy. Large declines in distress, which have been reported largely in the related studies cited in the Introduction, may be an artifact of extremely high loss to follow-up. Those findings were based on ten semi-annual assessments following an initial interview one week postabortion. Less than a third (32%) of eligible women approached to participate completed the initial interview. Of these women, only 54% remained in the sample to be re-interviewed at the 5-year follow-up. The 5-year results thus reflected only 17% of the women initially invited to participate. The authors acknowledged that “women with adverse mental health outcomes may have been less likely to participate and/or to be retained.” [

4] Söderberg et al., from experience with the 32% of non-respondents in their similar postabortion sample, similarly observed: “For many of the women, the reason for non-participation seemed to be a sense of guilt that they did not wish to discuss.” [

35] Loss to follow-up was monotonic, with about an additional 5% dropping out at each of ten biannual interviews, much like the perceived gradual decline in distress measures.

4.3. Policy Implications

In many jurisdictions legal termination of a healthy pregnancy is justified by a determination that doing so will benefit the mental health of the mother. The fact that a quarter of postabortive women experienced long-term emotional distress suggests that, as a therapeutic strategy for resolving stress associated with undesired pregnancies, induced abortion was often unsuccessful. Clinicians in such settings should develop robust screening procedures to identify patients at high risk of mental health harm or emotional distress, who should be provided appropriate support and/or advised of alternatives to abortion which are less likely to result in harm.

While the present study, as all studies in this area, has considered competing evidence for greater or lesser harm following an abortion, no evidence has yet demonstrated long-term mental health benefit (as opposed to short-term relief) from readily available abortion in any population of women.[

17,

36,

37] The persistent finding that, at its most benign, abortion may not result in general harm to women, is not consistent with a legal justification premised on general benefit for women, nor with the therapeutic goal to benefit the patient, not just avoid harm. By the standards of evidence-based medicine, no medical intervention can be justified where there is no evidence base of benefit.

4.4. Limitations

Some limitations of this study should be carefully noted. First, the data were based on retrospective self-reports, a method which is subject to loss of recall and subjective bias. The survey did not use validated measures of known disorders, such as depression or anxiety, which would have increased measurement precision and comparability. Although most survey items stipulated distress “due to the abortion,” other correlates not reported in this study make clear that by “the abortion” most women had in mind the relational and decision-making experiences of the abortion, and not their clinical procedure itself. No information was gathered about the characteristics of the abortion procedure. It is possible that some women conflated distress due to the abortion with troubles or stress stemming from other factors, in particular the pregnancy that preceded the abortion.

The tendency for women not to disclose having had an abortion limits the utility of almost every retrospective study of abortion. It is thus notable that in the data examined in this study there is little to no discernible abortion concealment. A total of 22.6% of this representative sample of 1000 U.S. women aged 41-45 reported having had at least one abortion. From age-adjusted abortion clinic incidence data, Jones estimated that 23.9% of American women had had an abortion before age 45 as of 2020.[

38] Such projections have been declining over time as the abortion rate has dropped; the corresponding projection as of 2008 was a 30% lifetime incidence of abortion. [

39] Interpolating the 2008 to 2020 decline two more years results in a count-based estimate that, as of 2022, 22.9% of American women will have experienced one or more abortions by age 45. Considering that the mean respondent age for the present data (42.9) is about two years younger than 45, it is difficult to find any significant abortion nonresponse in these data by comparison with external abortion counts.

4.5. Prevalence

The population sample examined in this study was statistically representative of an estimated 567,000 women with high post-abortion distress (PAD), reflecting over 2.3 million abortions, in the cohort of U.S. women aged 41-45 in 2022. Extending the proportion of abortions by age for this cohort to the rest of the female population yields an estimate of 31.3 million postabortive women in the U.S. population, of whom 7.5 million experience high PAD and 3.4 million experience multiple symptoms of PTS, as of 2022.

The size of this estimate may be surprising if only because the presence of large numbers of women with high PAD is seldom acknowledged. The needs and characteristics of this population, risk factors for persistent PAD, and effective therapeutic interventions, are all areas where research and evidence is notably sparse. Research is needed that explores the unique characteristics of PAD, with a view to establishing clinical interventions to serve this troubled population of women. This concern remains important whether or not the observed PAD was due to the abortion, the pregnancy prompting the abortion, prior mental health risk, or some other factor.

5. Conclusions

After twenty years most women are not troubled by a past abortion and still agree with their decision, but a significant minority doubt their decision and remain highly distressed by having had an abortion. Of the 31 million postabortive women in the United States, about 7.5 million (24%) suffer from serious post-abortion distress (PAD), with just under half of these (3.4 million) showing multiple symptoms of post-traumatic stress (PTS).

The health care of this population of women is understudied and underserved. Research is needed to better understand the risk factors for long-term emotional distress following an abortion and to develop effective therapeutic interventions. Women considering an abortion should be informed of the possibility that they may experience persistent emotional distress.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study. The author received general research funding from the Ruth Institute, Lake Charles, Louisiana, and from Sponsored Research Award 200803 at the Catholic University of America.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data collection for this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Sterling Institutional Review Board (IRB), Approval ID 10225. The present study engaged solely in a secondary analysis of this publicly available de-identified data, a use which has been determined by the United States Office of Human Protection of the Department of Health and Human Services to be exempt from human subject ethical review under 45 CFR 46.104.d (2018 revision).

Informed Consent Statement

“Broad written informed consent was obtained from or waived by all subjects involved in the study.”.

Data Availability Statement

The data file analyzed in this study is publicly available at the following reference: Reardon, David (2023), “The Effects of Abortion Decision Rightness and Decision Type on Women’s Satisfaction and Mental Health - Cureus 2023”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/5hgj345svc.1.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. The author has no connection with the Charlotte Lozier Institute. The author is a Catholic priest.

Note

| 1 |

Table 2, page 6 of [ 12] reports that of the 115 respondents with PTSS in the near-limits abortion group, 21% attributed their PTSS to an “index pregnancy-related event,” including 14% who specified the “abortion experience or decision.” Similarly, 14% of the 101 women with PTSS in the first-trimester abortion group cited the index pregnancy, including 8% who specified the abortion experience or decision. Resolving these percentages reveals that, of all women with PTSS who had an abortion, 30 of 47, or 63.8%, of those citing the index pregnancy attributed their PTSS to the abortion experience of decision. |

References

- Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion, A.P.A. Report of the Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion.; 2008;

- Turell, S.C.; Armsworth, M.W.; Gaa, J.P. Emotional Response to Abortion: A Critical Review of the Literature. Women Ther. 1990, 9, 49–68. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, M.A.; Neuhaus, J.M.; Foster, D.G. Mental Health Diagnoses 3 Years After Receiving or Being Denied an Abortion in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2557–2563. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, M.A.; Upadhyay, U.D.; McCulloch, C.E.; Foster, D.G. Women’s Mental Health and Well-Being 5 Years After Receiving or Being Denied an Abortion: A Prospective, Longitudinal Cohort Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 169–178. [CrossRef]

- Rocca, C.H.; Samari, G.; Foster, D.G.; Gould, H.; Kimport, K. Emotions and Decision Rightness over Five Years Following an Abortion: An Examination of Decision Difficulty and Abortion Stigma. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 248, 112704. [CrossRef]

- Broen, A.N.; Moum, T.; Bödtker, A.S.; Ekeberg, Ö. Predictors of Anxiety and Depression Following Pregnancy Termination: A Longitudinal Five-Year Follow-up Study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2006, 85, 317–323. [CrossRef]

- Major B; Cozzarelli C; Cooper M; et al PSychological Responses of Women after First-Trimester Abortion. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 777–784. [CrossRef]

- Rees, D.I.; Sabia, J.J. The Relationship between Abortion and Depression: New Evidence from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. Ann. Transplant. 2007, 13, CR430–CR436.

- Curley, M.; Johnston, C. The Characteristics and Severity of Psychological Distress After Abortion Among University Students. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 40, 279–293. [CrossRef]

- Koop, C.E. The Federal Role in Determining the Medical and Psychological Impact of Abortions on Women. Testimony given to the Committee on Government Operations, U.S. House of Representatives, 101st Congress, 2nd Session, December 11, 1989. (HR No. 101-392) 1989.

- Rocca, C.H.; Kimport, K.; Gould, H.; Foster, D.G. Women’s Emotions One Week After Receiving or Being Denied an Abortion in the United States. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2013, 45, 122–131. [CrossRef]

- Biggs, M.A.; Rowland, B.; McCulloch, C.; Foster, D.G. Does Abortion Increase Women’s Risk for Post-Traumatic Stress? Findings from a Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2016, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Sit, D.; Rothschild, A.J.; Creinin, M.D.; Hanusa, B.H.; Wisner, K.L. Psychiatric Outcomes Following Medical and Surgical Abortion. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2007, 22, 878–884. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Pires, R.; Canavarro, M.C. Psychosocial Adjustment after Induced Abortion and Its Explanatory Factors among Adolescent and Adult Women. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2017, 35, 119–136. [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.T.; Harvey, S.M.; Henderson, J.T. Do Depression and Low Self-Esteem Follow Abortion among Adolescents? Evidence from a National Study. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2010, 42, 230–235. [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, H.; Janzon, L.; Sjöberg, N.-O. Emotional Distress Following Induced Abortion: A Study of Its Incidence and Determinants among Abortees in Malmö, Sweden. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1998, 79, 173–178. [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J.; Boden, J.M. Abortion and Mental Health Disorders: Evidence from a 30-Year Longitudinal Study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 193, 444–451. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, W. Abortion and Depression: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study of Young Women. Scand. J. Public Health 2008, 36, 424–428. [CrossRef]

- Schmiege, S.; Russo, N.F. Depression And Unwanted First Pregnancy: Longitudinal Cohort Study. BMJ 2005, 331, 1303–1306. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, J.R.; Finer, L.B. Examining the Association of Abortion History and Current Mental Health: A Reanalysis of the National Comorbidity Survey Using a Common-Risk-Factors Model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 72–82. [CrossRef]

- Sullins, D.P. Abortion, Substance Abuse and Mental Health in Early Adulthood: Thirteen-Year Longitudinal Evidence from the United States. SAGE Open Med. 2016, 4, 2050312116665997. [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J.; Ridder, E.M. Abortion in Young Women and Subsequent Mental Health. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, W. Childbirth, Abortion and Subsequent Substance Use in Young Women: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study. Addict. Abingdon Engl. 2007, 102, 1971–1978. [CrossRef]

- Sullins, D.P. Affective and Substance Abuse Disorders Following Abortion by Pregnancy Intention in the United States: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Medicina (Mex.) 2019, 55, 741. [CrossRef]

- Reardon, D.C.; Rafferty, K.A.; Longbons, T. The Effects of Abortion Decision Rightness and Decision Type on Women’s Satisfaction and Mental Health. Curēus Palo Alto CA 2023, 15, e38882–e38882. [CrossRef]

- Reardon, D.C.; Longbons, T. Effects of Pressure to Abort on Women’s Emotional Responses and Mental Health. Curēus Palo Alto CA 2023, 15, e34456–e34456. [CrossRef]

- Reardon The Effects of Abortion Decision Rightness and Decision Type on Women’s Satisfaction and Mental Health - Cureus 2023 - Mendelay Data, Version 1. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bureau, U.S. Census National Population by Characteristics: 2020-2023: Monthly Population Estimates by Age, Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2022 (NC-EST2022-ALLDATA) Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-national-detail.html (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- US Census Bureau Income in the United States: 2022-Current Population Reports, Figure 6, Female-to-Male Earnings Ration and Median Earning of Full-Time, Year-Round Workers 15 Year and Older by Sex: 1960 to 2022 Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2023/demo/p60-279.html (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- US Census Bureau Educational Attainment in the United States: 2021; Table 2 Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2021/demo/educational-attainment/cps-detailed-tables.html (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- American Psychiatric Association Desk Reference to the Diagnostic Criteria from DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, 2013;

- Biggs, M.A.; Rowland, B.; Foster, D.G. Does Abortion Increase Women’s Risk for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder? Contraception 2015, 92, 359. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, N.; Eryavec, G. Delayed Onset Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in World War Ii Veterans. Can. J. Psychiatry 1994, 39, 439–441. [CrossRef]

- Horesh, D.; Solomon, Z.; Zerach, G.; Ein-Dor, T. Delayed-Onset PTSD among War Veterans: The Role of Life Events throughout the Life Cycle. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 863–870. [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, H.; Andersson, C.; Janzon, L.; Nils-Otto Sjöberg Selection Bias in a Study on How Women Experienced Induced Abortion. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1997, 77, 67–70. [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.M. Abortion and Mental Health. Psychiatr. Bull. 2008, 32, 321–324. [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D.M.; Horwood, L.J.; Boden, J.M. Does Abortion Reduce the Mental Health Risks of Unwanted or Unintended Pregnancy? A Re-Appraisal of the Evidence. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2013, 47, 819–827. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.K. An Estimate of Lifetime Incidence of Abortion in the United States Using the 2021–2022 Abortion Patient Survey. Contraception 2024, 135, 110445. [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.K.; Kavanaugh, M.L. Changes in Abortion Rates Between 2000 and 2008 and Lifetime Incidence of Abortion. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 117, 1358. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Effects of weight adjustment for distribution of population and abortions by ethnicity: Probability Sample of U.S. Women aged 41-45 (N=1000).

Table 1.

Effects of weight adjustment for distribution of population and abortions by ethnicity: Probability Sample of U.S. Women aged 41-45 (N=1000).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of the sample by abortion exposure, counts, and weighted proportions: Probability sample of Women aged 41-45, United States, 2022 (N=1,000).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of the sample by abortion exposure, counts, and weighted proportions: Probability sample of Women aged 41-45, United States, 2022 (N=1,000).

| |

Overall Sample (N=1,000) |

Ever Abortion |

| NO (N=774) |

YES (N=226) |

| Income |

Count |

Percent (CI) |

Count |

Percent (CI) |

Count |

Percent (CI) |

| |

Less than $25,000 |

134 |

13.0 (11.0-15.4) |

107 |

13.0 (1.1-15.5) |

27 |

13.3 (8.8-19.6) |

| |

$25,000-$49,999 |

148 |

15.0 (12.7-17.6) |

116 |

13.9 (11.6-16.6) |

35 |

18.7 (12.9-26.2) |

| |

$50,000-$74,999 |

265 |

27.7 (24.8-30.8) |

201 |

27.0 (23.8-30.3) |

64 |

30.1 (23.5-37.6) |

| |

$75,000-$99,999 |

188 |

18.5 (16.1-21.1) |

144 |

19.2 (16.5-22.2) |

44 |

16.1 (11.7-21.7) |

| |

$100,000 or more |

265 |

25.8 (23.1-28.7) |

206 |

26.9 (23.9-30.3) |

59 |

21.8 (16.5-28.3) |

| Educational attainment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

High school diploma or less |

363 |

37.3 (34.2-40.6) |

283 |

36.3 (32.9-39.9) |

80 |

41.0 (33.6-48.8) |

| |

University degree |

456 |

44.9 (41.6-48.1) |

345 |

44.5 (40.9-48.1) |

111 |

46.2 (38.7-53.8) |

| |

Postgraduate education |

181 |

17.8 (15.5-20.4) |

146 |

19.2 (16.5-22.2) |

35 |

12.8 (8.9-18.2) |

| Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

White |

592 |

55.9 (52.5-59.2) |

464 |

61.4 (57.8-64.9) |

128 |

37.2 (30.9-43.9) |

| |

Black |

150 |

14.5 (12.1-17.3) |

118 |

9.3 (7.8-11.1) |

32 |

32.3 (24.6-41.1) |

| |

Hispanic |

137 |

20.2 (17.4-23.3) |

103 |

19.5 (16.4-23.0) |

34 |

22.6 (16.7-29.8) |

| |

Asian |

48 |

3.7 (2.8-4.9) |

35 |

3.9 (2.8-5.3) |

13 |

3.2 (1.9-5.6) |

| |

Other racial/ethnic identity |

73 |

5.7 (4.5-7.1) |

54 |

6.0 (4.7-7.7) |

19 |

4.7 (3.0-7.4) |

| Region |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Midwest |

209 |

20.4 (17.8-23.2) |

167 |

21.5 (18.7-24.6) |

42 |

16.9 (12.0-23.3) |

| |

Northeast |

144 |

14.8 (12.6-17.4) |

108 |

14.2 (11.9-17.0) |

36 |

16.9 (11.9-23.6) |

| |

South |

437 |

43.4 (40.2-46.7) |

339 |

42.7 (39.2-46.3) |

98 |

45.9 (38.5-53.6) |

| |

West |

210 |

21.3 (18.7-24.1) |

160 |

21.6 (18.7-24.8) |

50 |

20.2 (15.0-26.6) |

Table 3.

Four scaled measures of distress about the abortion among ever-aborting women (N=226): Probability Sample of U.S. Women aged 41-45 (N=1,000).

Table 3.

Four scaled measures of distress about the abortion among ever-aborting women (N=226): Probability Sample of U.S. Women aged 41-45 (N=1,000).

| |

|

Quintile Distribution |

|

Mean (SE) |

| 0-20 |

21-40 |

41-60 |

61-80 |

81-100 |

| |

Left

Side |

Low (n=128) |

Moderate (n=40) |

High (n=58) |

Right Side |

|

| Very |

Some

what |

Some

what |

Very |

| My negative emotions regarding the abortion are . . . |

None at all |

21.1% |

17.6% |

23.6% |

14.9% |

22.8% |

Very High |

51.1

(2.4) |

| I have had frequent feelings of loss, grief, sadness about the abortion. |

Not at all true |

39.4% |

15.2% |

14.3% |

16.2% |

15.0% |

Very True |

39.6

(2.7) |

| Thoughts and feelings about my abortion have negatively interfered with daily life, work, or relationships. |

Not at all true |

39.3% |

21.1% |

16.4% |

10.5% |

12.7% |

Very True |

36.0

(2.5) |

| I have had frequent thoughts, dreams, or flashbacks to the abortion. |

Not at all true |

43.0% |

15.7% |

16.7% |

11.6% |

13.0% |

Very True |

35.5

(2.5) |

| |

|

Combined Metrics |

|

|

| |

|

Low (0-40) |

Moderate

(41-60) |

High (61-100) |

|

|

| Percent response in the indicated column(s) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| On at least one item |

|

75.5 |

45.5 |

47.9 |

|

|

| On at least two items |

|

62.1 |

16.6 |

34.7 |

|

|

| On at least three items |

|

47.9 |

5.8 |

23.0 |

|

|

| On all four items |

|

26.9 |

3.2 |

11.0 |

|

|

Average (additive scaled) response

over all 4 items (alpha = .88) |

|

55.2 |

20.7 |

24.1 |

|

40.6

(2.1) |

Table 4.

Postabortion distress (PAD) by demographic characteristics, showing weighted row percents: Ever-aborting women aged 41-45, United States, 2022 (N=226).

Table 4.

Postabortion distress (PAD) by demographic characteristics, showing weighted row percents: Ever-aborting women aged 41-45, United States, 2022 (N=226).

| |

Percent High PAD (N=58) |

| |

|

Percent (CI) |

| Overall |

|

24.1 (18.3-31.1) |

| Income |

|

|

| |

Less than $25,000 |

|

24.5 (10.9-46.2) |

| |

$25,000-$49,999 |

|

28.7 (14.3-49.2) |

| |

$50,000-$74,999 |

|

20.2 (11.7-32.6) |

| |

$75,000-$99,999 |

|

23.2 (11.9-40.2) |

| |

$100,000 or more |

|

26.1 (15.0-41.5) |

| Educational attainment |

|

| |

High school diploma or less |

|

27.8 (17.7-40.8) |

| |

University degree |

|

18.1 (11.7-27.0) |

| |

Postgraduate education |

|

33.9 (19.2-52.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

| |

White |

|

27.3 (20.2-35.8) |

| |

Black |

|

21.9 (10.3-40.4) |

| |

Hispanic |

|

20.6 (9.7-38.4) |

| |

Asian |

|

15.4 (3.1-51.0) |

| |

Other racial/ethnic identity |

|

36.8 (17.3-62.0) |

| Region |

|

|

| |

Midwest |

|

16.2 (8.3-29.0) |

| |

Northeast |

|

35.0 (19.5-54.4) |

| |

South |

|

22.4 (14.2-33.6) |

| |

West |

|

25.5 (14.2-41.6) |

Table 5.

Population estimates of postabortive women and associated distress: Probability sample of Women aged 41-45, United States, 2022 (N=1,000).

Table 5.

Population estimates of postabortive women and associated distress: Probability sample of Women aged 41-45, United States, 2022 (N=1,000).

| |

Post Abortive Women |

Population Estimates |

| By Age |

Cumulative Percent of Abortions |

Cumulative Population Percent Postabortive |

Period Median |

Population Cohort (Age 15+) |

Postabortive Women |

Women with High PAD |

Women with Four or more PTS Symptoms |

| |

19 |

37.5 |

8.48 |

4.24 |

10,553,749 |

447,479 |

107,842 |

49,223 |

| |

24 |

75.3 |

17.01 |

12.75 |

11,103,791 |

1,415,733 |

341,192 |

155,731 |

| |

29 |

86.1 |

19.46 |

18.24 |

10,840,422 |

1,977,293 |

476,528 |

217,502 |

| |

34 |

100 |

22.6 |

21.03 |

11,471,316 |

2,412,418 |

581,392 |

265,366 |

| |

93 |

100 |

22.6 |

22.6 |

94,327,838 |

21,318,091 |

5,137,660 |

2,344,990 |

| Total |

100 |

22.6 |

22.6 |

138,297,116 |

31,255,148 |

7,532,491 |

3,438,066 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).