1. Introduction

Plant viruses have been traditionally viewed as pathogens and parasites because outbreaks in crops of symptomatic viral infections can cause very important economic losses. However, it has been suggested that this view may be biased [

1], for mainly two reasons: on the one hand, it has been shown that some symptomatic infections, in experimental plants or in crops, can increase the tolerance of the host to additional biotic or non-biotic stresses, notably drought [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], although this is by no means the case in all virus/host patho-systems [

10]. On the other hand, it has been observed that in nature many infections cause little or no symptoms, and tend to be persistent [

1,

11,

12]. Together, the benefits that infections give to the host in its response to additional stresses, and the presence in nature of attenuated or cryptic infections, add a symbiotic mutualistic dimension to plant-virus interactions [

1].

Beneficial effects to plants of symptomatic viral infections when they cope with additional stresses derive from the alterations in host gene expression that infections induce, which have physiology and morphology effects. Physiology alterations can originate from the use by the virus of plant molecular resources to multiply and disperse, and also from the activation of plant resistance responses. These can be specific, such as is the small RNA (sRNA)-based interference targeted at viral genetic material that have sequence homology to those sRNAs [

13], or generic, such as systemic acquired resistance, or immunity responses triggered when plant receptors recognize some pathogen material (protein or genetic) as alien. With regard to the former, it has been recently shown for the first time that that an sRNA of viral sequence induced by the plant silencing machinery during infection of common beans by a

Carlavirus induces the downregulation of a host gene via the autophagy pathway, which itself regulates positively stomatal aperture, thus providing in this way some protection against drought to infected plants [

8]. With regard to the latter generic responses, in them cascades of interlinked pathways are activated that lead to metabolic re-programming, in which hormones are also involved [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20], which can provide generic, unspecific protection to pathogens.

Viruses need to compensate or neutralize both these responses in order to infect plants successfully, and to do that, they express specific factors that interfere with antiviral silencing defenses, such as silencing suppressors [

21], and with generic immunity responses, which could be the same factors that also have suppressor function, or different ones [

22,

23]. Interference from viral suppressors with endogenous plant sRNA-mediated regulation, development pathways, and responses to stresses [

24] also lead on the other hand to pathologies.

Changes in physiology caused by infection, and the responses to infection can thus lead to pathogenesis and to changes in the morphology of the plant [

25]. Common symptoms include plant stunting and affections to leaves during their development that create chlorotic mosaics in their mesophyll or vasculature, deformation, curling, and overall thickening, relative to fully expanded, healthy leaves. It is noteworthy to mention that these physical changes, common to many symptomatic infections, can by themselves alter gas exchanges between plants and their environment, when compared to uninfected plants or to plants with asymptomatic infections. The contribution of symptomatic infections to the responses of plants to ambient stresses is thus intermingled with the alterations in plant morphology that they induce.

Our knowledge on physiology effects of infections by RNA viruses and how they affect plant responses to additional biotic or abiotic stresses comes mainly from infections that are symptomatic to different degrees [

2,

3,

6,

7,

9], despite asymptomatic or latent infections as defined by [

26], being common in nature. Remarkably, information available on asymptomatic infections originates mainly from viruses that originally were symptomatic: one source of information are infections by symptomatic viruses that become latent or attenuated when mutations affect negatively essential functions of their viral factors, and is usually associated with reduced viral levels. This effect has been the basis for cross-protection, a practice used to prevent ulterior infections by more pathogenic virus strains. Targets for such mutations are often the viral suppressors of silencing. In this regard,

Potyvirus suppressor-deficient variants have been generated in the lab by site-directed mutagenesis in the silencing-suppressor HCPro [

27,

28,

29,

30]. In this regard, a lab-generated tobacco vein banding mosaic virus (TVBMV) variant, expressing a mutated, suppression-deficient HCPro, was used by [

30] to characterize transcriptome and hormone expression changes that it induced in its attenuated infection of

Nicotiana benthamiana, relative to uninfected plants. However, the work did not analyze the effect of infection on the host response to an additional stress. Additional reported sources of asymptomatic infections involve chimeric viruses such as a lab-generated plum pox virus/PVY potyvirus that is initially un-adapted to this host [

31]. However, it can adapt naturally with time, and increase its virulence, by incorporating mutations in its HCPro [

32]. Mutations in the viral replicase of the

Tobamovirus pepper mild mottle virus, which also has the suppressor function, are also reported to create attenuated viruses, capable of providing cross protection [

33].

A second source of information on beneficial effects of asymptomatic infections to abiotic stresses comes from intact symptomatic viruses without functional deficiencies in their essential factors, when they infect plants that harbor resistances to them, thus displaying attenuated symptoms. This is for example the case of a tomato yellow leaf curl geminivirus (TYLCV) isolate in its systemic infection of a resistant tomato (line GF967; [

34]). In this case, correlation was found between a differential accumulation of osmo-protectants in the plants latently infected and their enhanced tolerance to drought, relative to uninfected plants [

34].

There is a potential third source of data on asymptomatic infections that involves infection of a compatible host by a normally symptomatic virus, under ambient conditions that turn it asymptomatic. In this third case both, virus and host would be unaltered. It is known that infections alter their pathogenicity when ambient parameter thresholds are surpassed [

2,

35,

36,

37,

38]. In this regard, we had previously described that infection of

N. benthamiana plants by a potato virus Y (PVY

O) isolate shifted from causing severe symptoms (stunting, leaf curling, even death in small plantlets) under conditions of 25 °C and ~405 parts-per-million (ppm) CO

2 levels, to being asymptomatic under conditions of 30 °C and 970 ppm of CO

2 with viral titers being very low [

37,

38]. We have determined here under these latter ambient conditions, how infection by PVY affects the physiology of

N. benthamiana plants, and its interplay with drought, when the two are combined.

4. Discussion

Plant viruses have co-evolved with terrestrial plants with flowers since the latter appeared around two hundred million years ago, and diversified enormously, and also with their dispersing vectors. Compatible interactions have developed during this coevolution, which are determined by specific molecular interactions. They have led in many instances to natural infections that are cryptic, or near asymptomatic [

1,

11]. In addition to this, it has been shown that some symptomatic viral infections can benefit infected hosts in their broader interaction with the environment, for example in their responses to drought [

2,

3,

7,

9], thus providing beneficial trade-offs to the infected host that may ultimately also help the virus remain in the environment. These two observations have given a symbiotic edge to plant/virus interactions, and to their co-evolution. However, we still view viruses as basically parasitic entities because they “sequester” the cellular machinery to complete their biological cycle, and because infection outbreaks cause important losses to agriculture.

Extensive literature is available on how infections by viruses that are symptomatic to different degrees affect crops in their physiology. In the case of PVY, effects on the metabolome of potato plants by different viral variants of different infection severity are available [

44,

45]. However, infection on physiology effects of an infection induced by a normally symptomatic virus in a normally compatible host when it turns asymptomatic not only asymptomatic but subliminal because of environmental conditions is not available. The latter is however the scenario of the patho-system PVY

O/

N. benthamiana under circumstances of elevated temperature (30 °C) and CO

2 levels: the virus is still able to infect the plants systemically, but with a near ten-fold drop in viral titers, and an absence of visual infection symptoms [

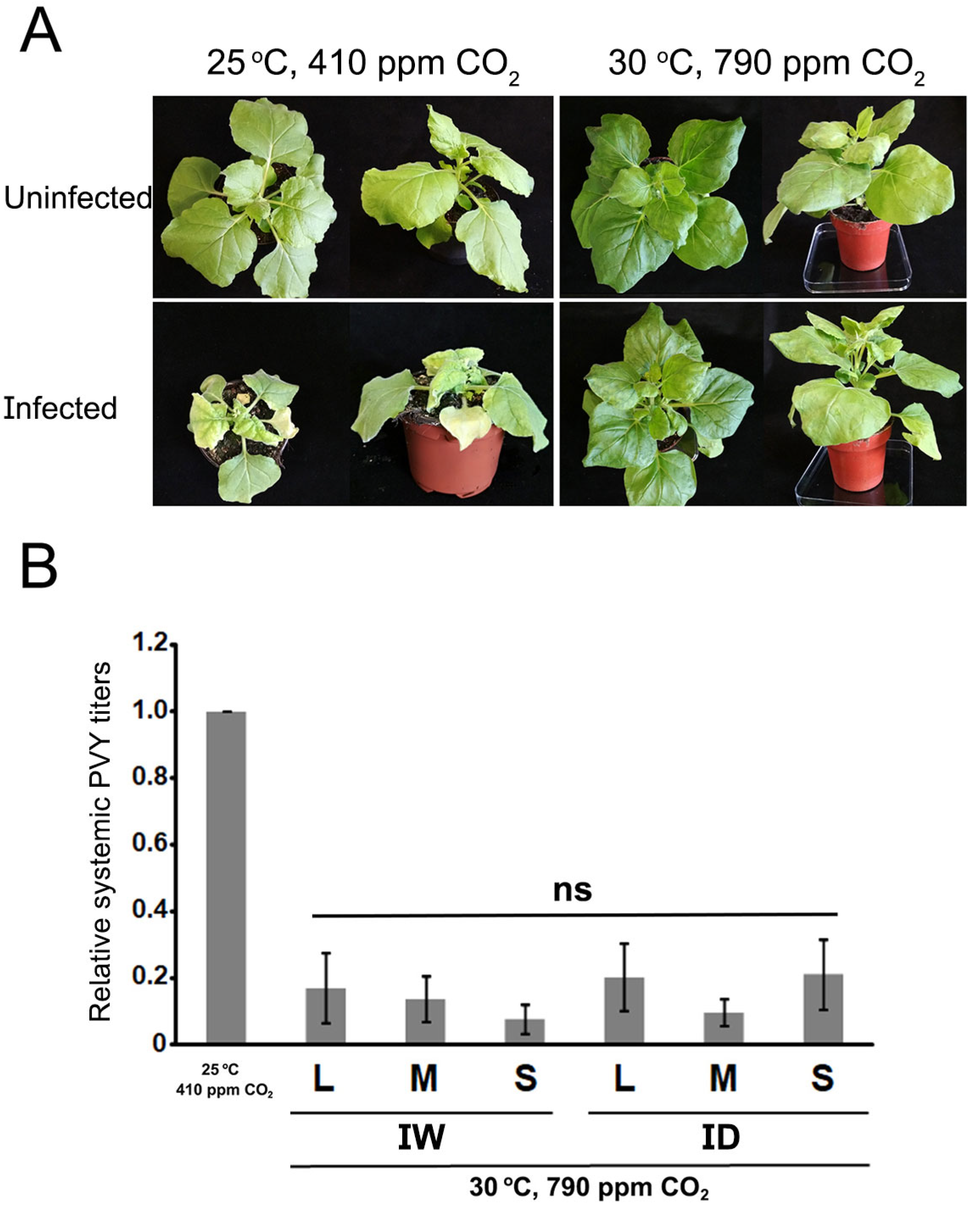

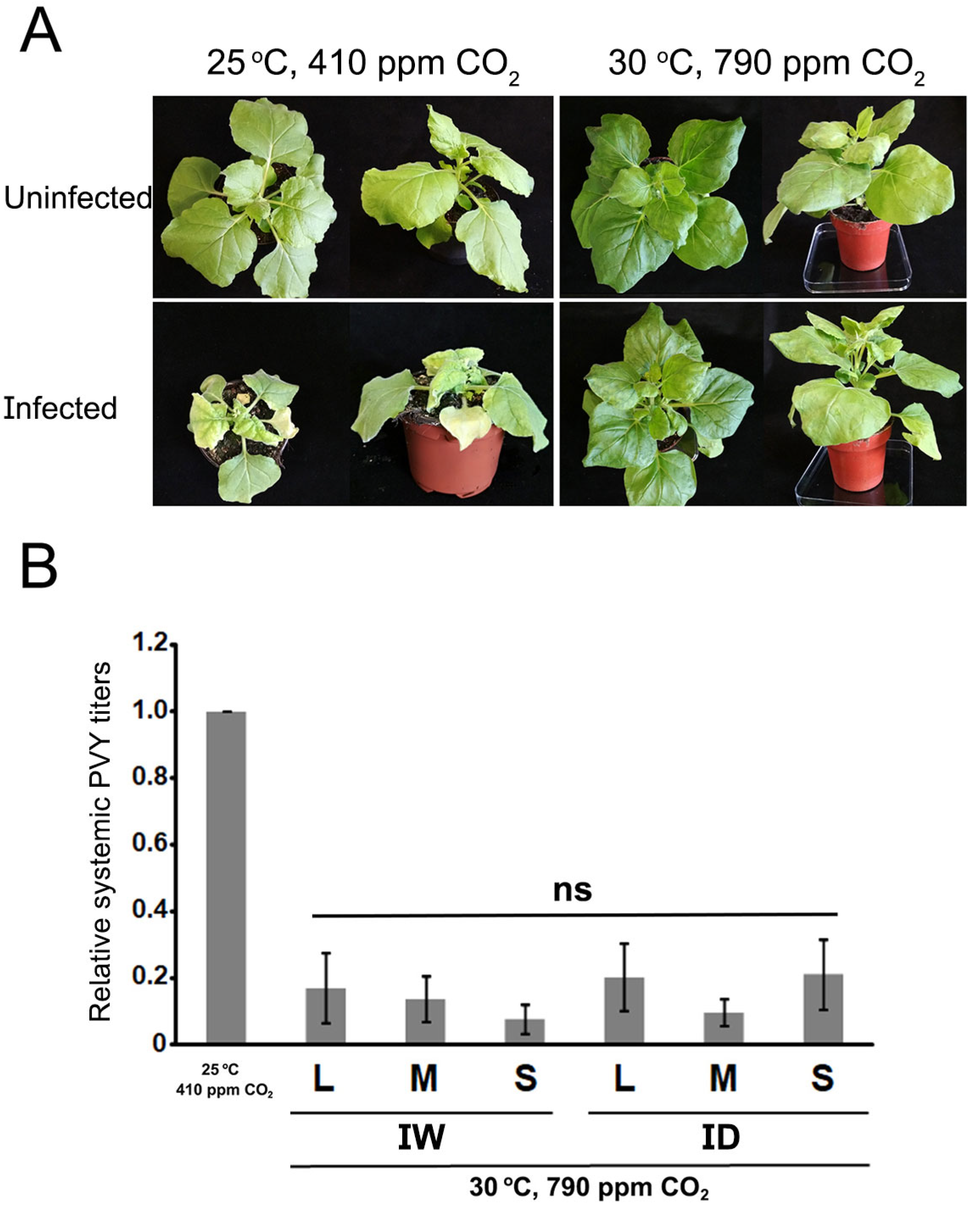

37,

38] (

Figure 2). The infection is thus not only asymptomatic but subliminal. This gave us the opportunity to study whether and how such an infection of a normal experimental plant by a normal virus could affect the physiology of the plant, and its interplay with another abiotic stress, drought. It also allowed us to dissect effects on physiology parameters that are caused directly by the infection itself from secondary ones that could be caused by alterations in morphology that the infection induces in this host (such as in its water exchange with the atmosphere), which in the

N. benthamiana/PVY system are severe under standard ambient conditions: chlorosis mosaics in leaves, leaf curling and thickening, plant stunting, and even death in small plantlets.

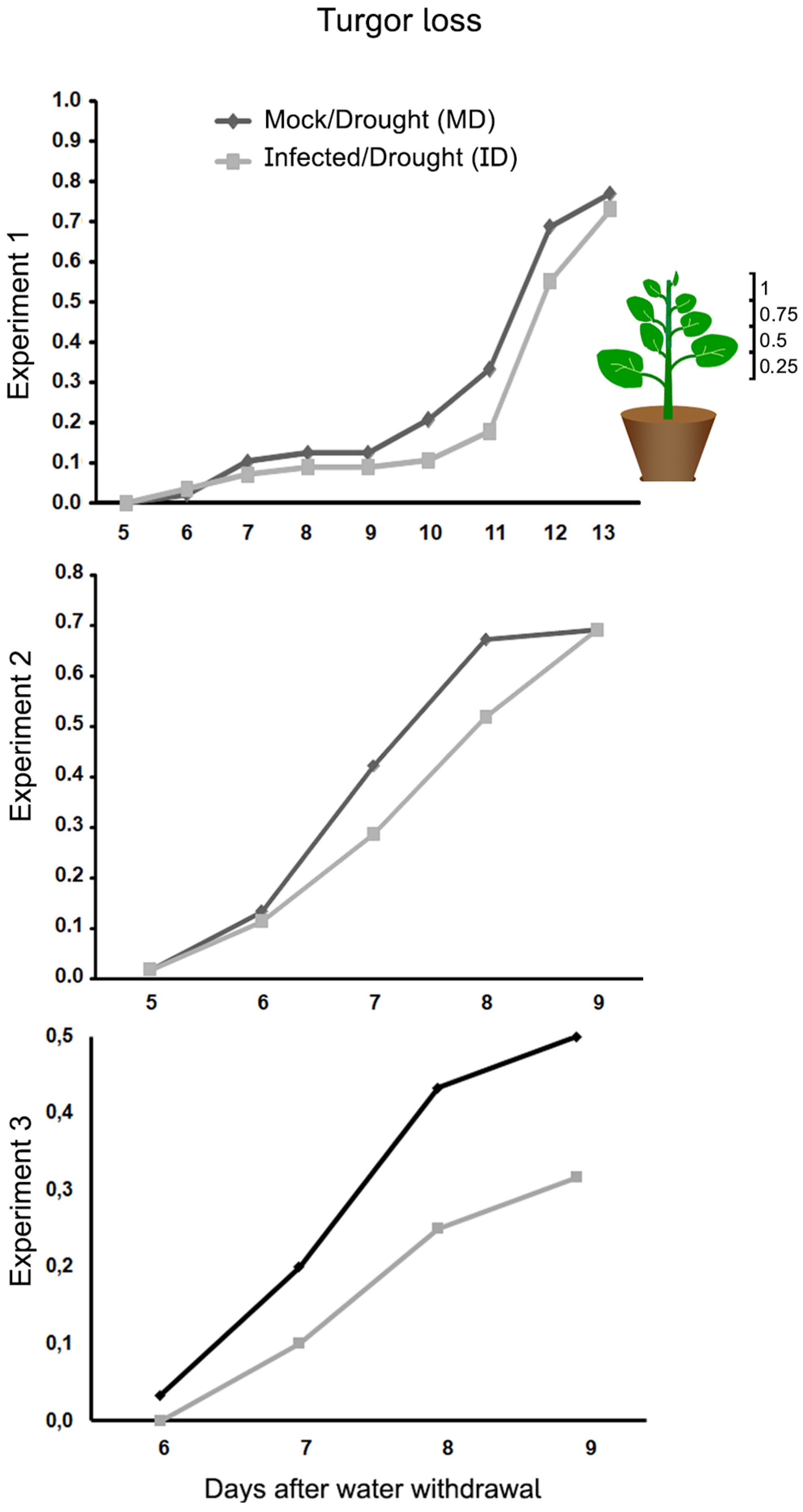

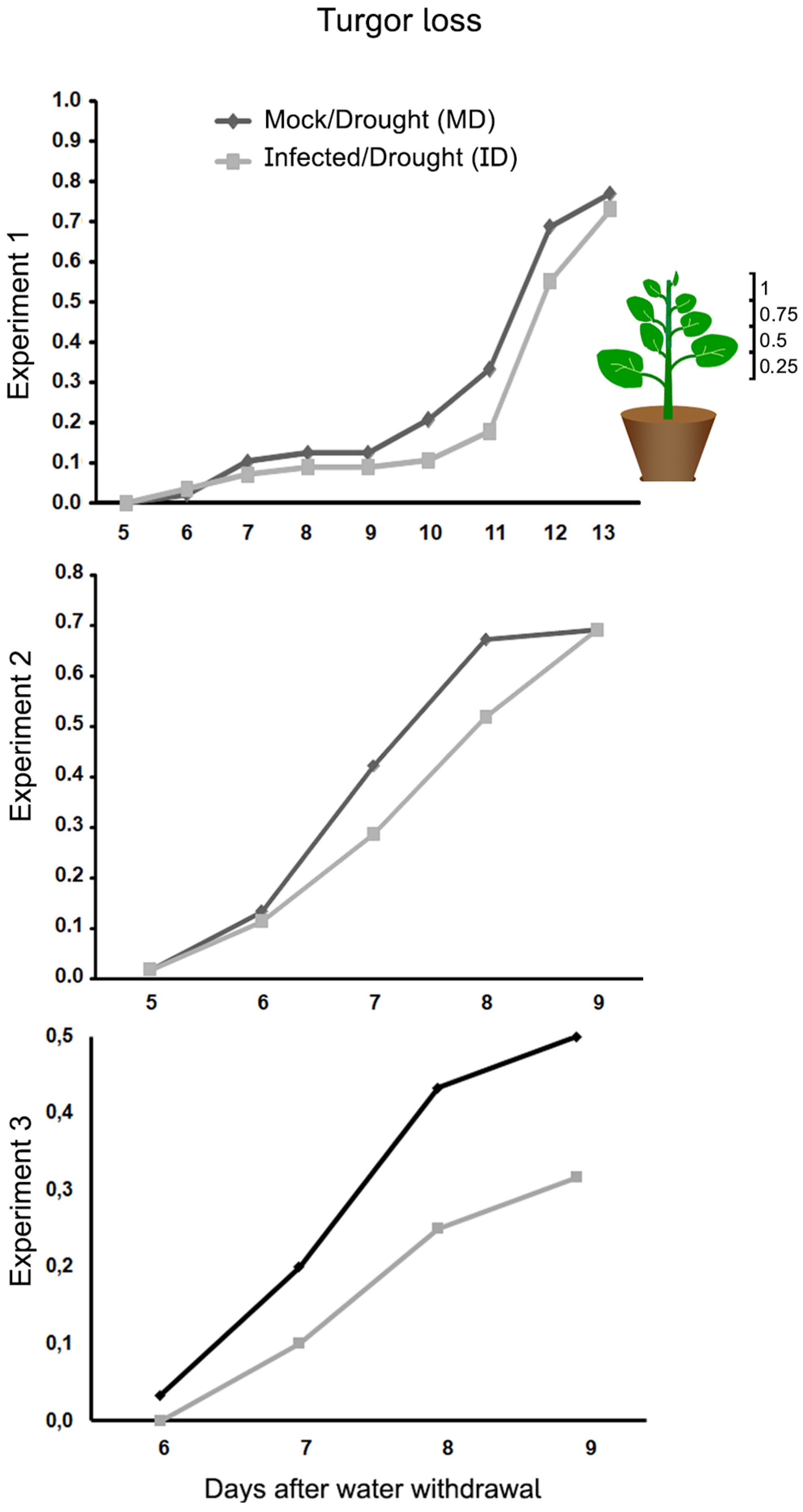

We assessed whether the asymptomatic infection had any effect on loss of leaf turgor progression in three separate experiments, and we observed a slight delay in its appearance in infected vs. mock plants in the three experiments (

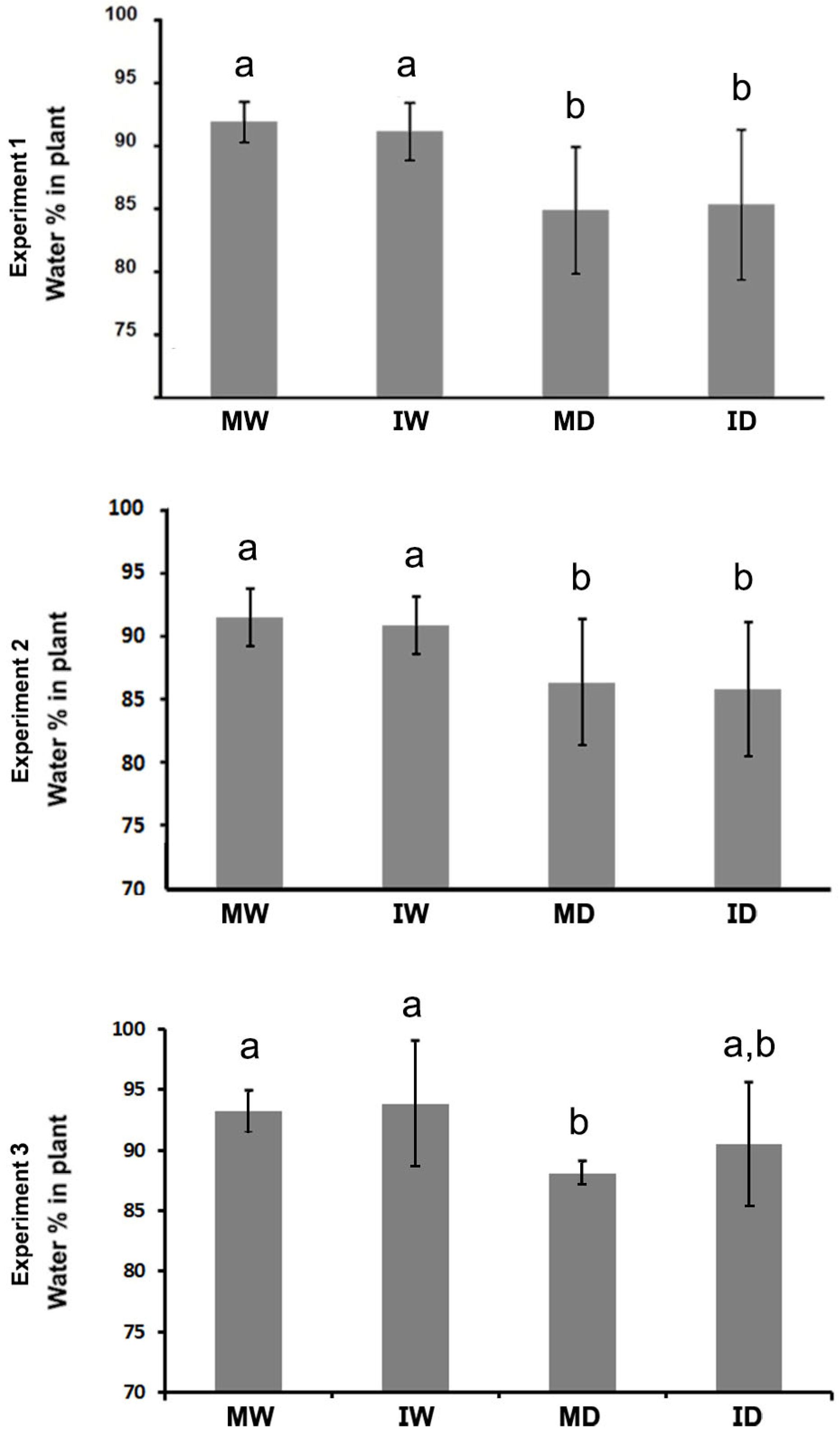

Figure 3). However, this delay was not statistically significant for any of the time points assessed. In addition, in experiments 1 and 2 the loss of turgor converged at the end of both experiments, but not at the end of experiment 3, which could have had more time to continue. It should be noted that measures of total plant water content are taken at the end of the experiments because they require the destruction of the plant. We thus lack information on the evolution of plant water content at intermediate times during the experiments. However, given the turgor data, water content at the end of experiment 3 could be considered equivalent to measuring water content at an intermediate time in the other two experiments. Interestingly, experiment 3 is the only experiment in which an effect of infection on final plant water content could be observed: infection did not alter significantly the final plant water content in experiments 1 and 2 under conditions of drought, but in experiment 3 that loss of water content appeared attenuated in the infected plants, to the point of being not significant when compared to well-watered plants (ID vs. MW and IW;

Figure 4). Thus, the asymptomatic infection has no negative effect on the response of the plant to drought, and could have a positive yet temporary effect on the ability of the plant to keep its water content.

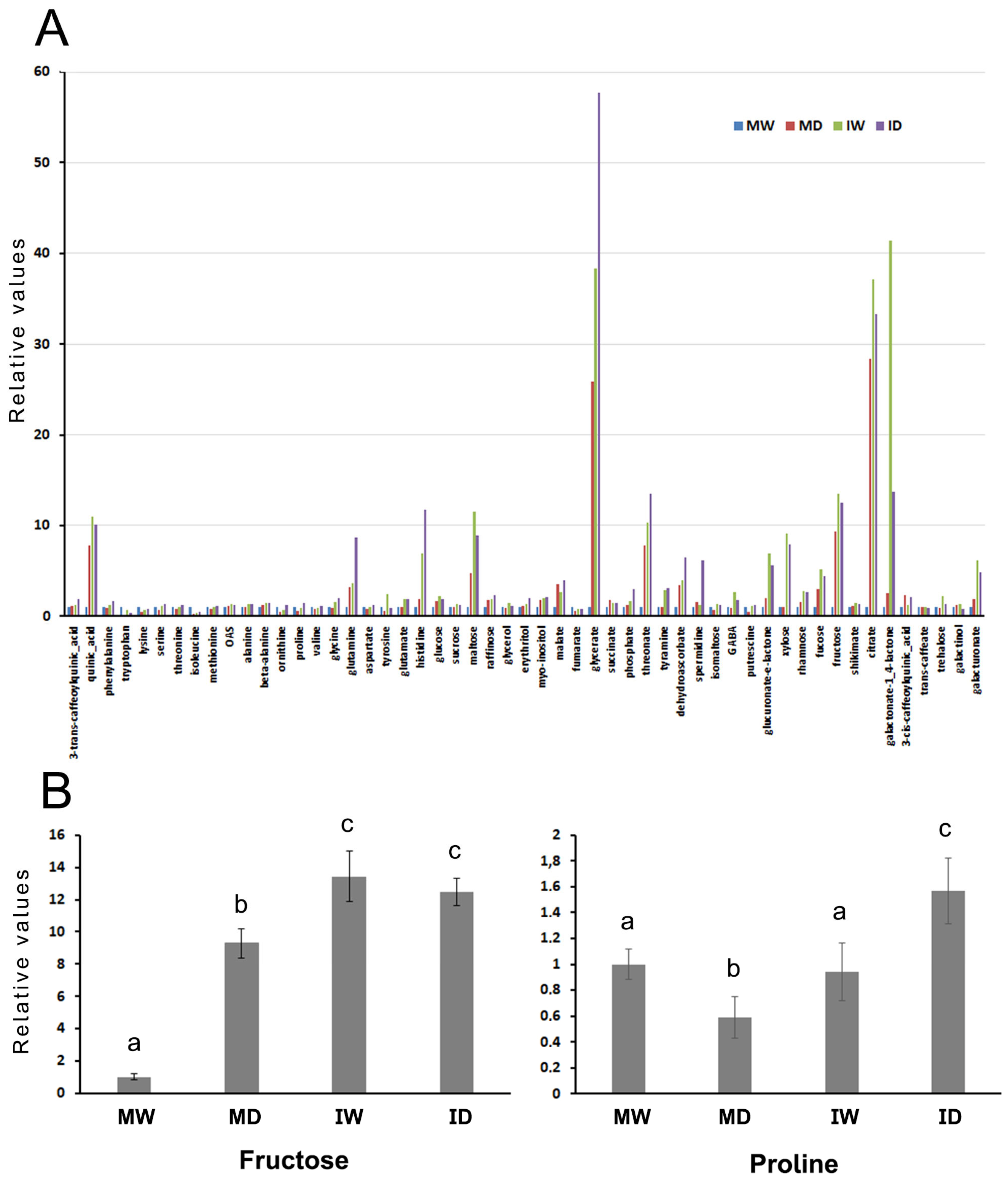

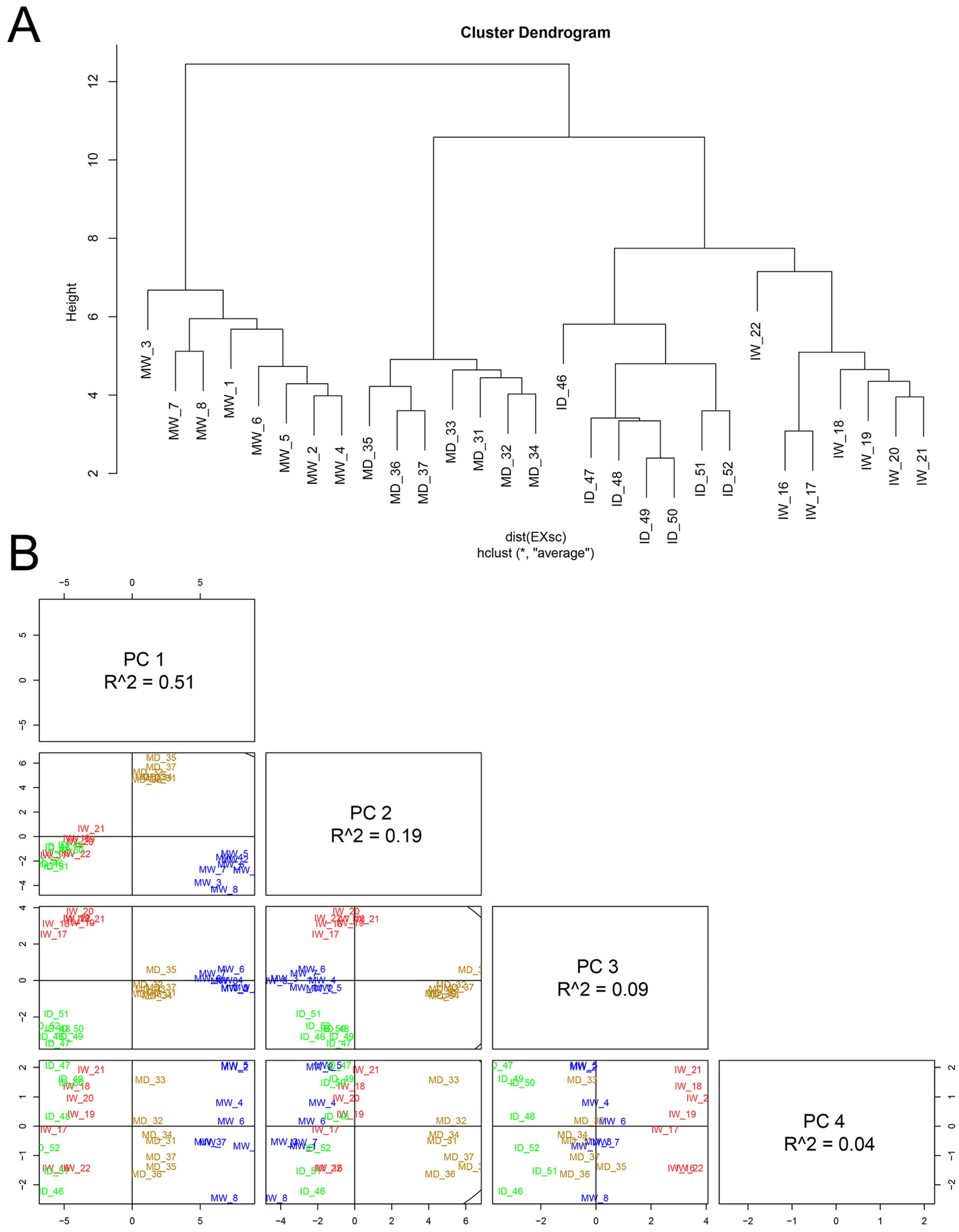

With regard to metabolic alterations, we found that those induced by either the asymptomatic infection of

N. benthamiana by our PVY

O isolate at 30 °C and 970 ppm of CO

2, by drought, or by the two combined were all significant, despite the absence of visible symptoms caused by infection (

Figure 6). Alterations induced by infection alone were of a scale comparable to those induced by drought, although affecting the 53 compounds differently (

Figure 6). In this regard, there were increases in the levels of some compounds caused by infection alone that were not induced by drought, or to a much lesser extent. However, the reverse was far less common: increases in the levels of some compounds induced by drought alone that were not also matched, or induced to higher levels by infection. When drought and infection combined, the latter increased further the levels of some sugars, such as fructose, and those of other osmo-protectants, such as glutamine (

Figure 6). This could help the plant protect itself temporarily against drought, and explain the data on final water content in experiment 3 (

Figure 4).

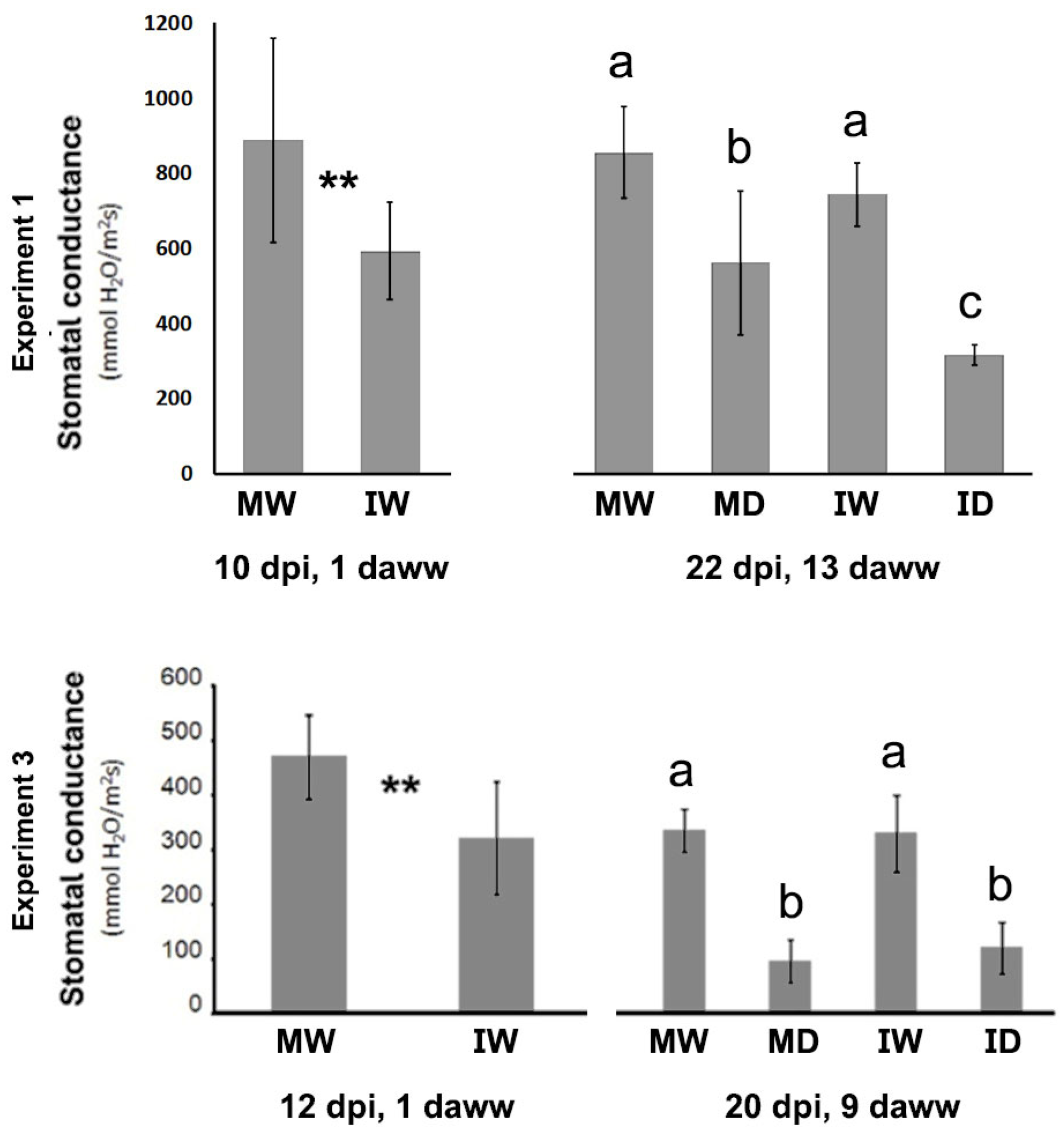

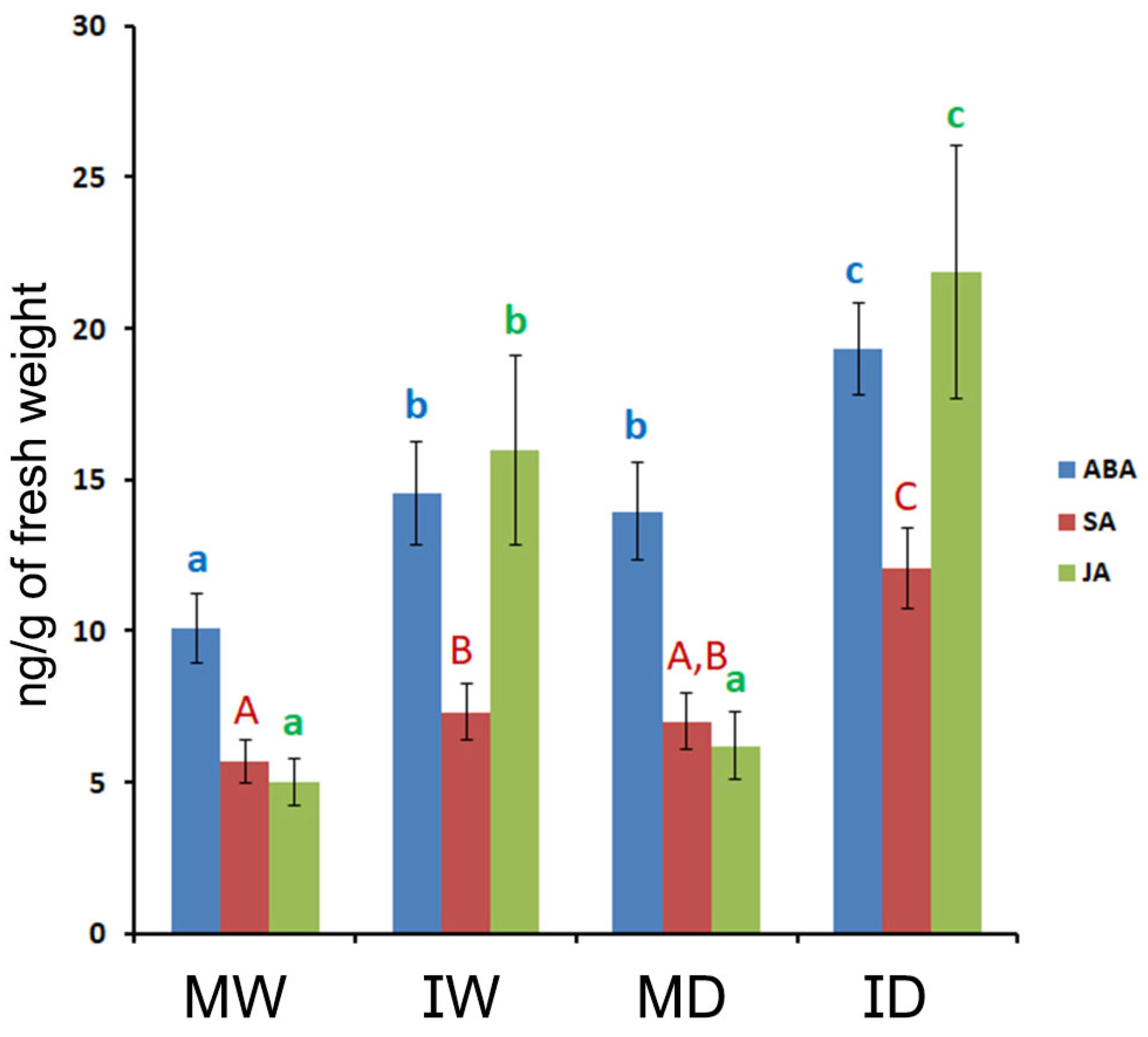

With regard to hormone levels, drought only caused a significant increase in the levels of ABA (

Figure 8), which would explain the stomatal closure and reduced conductance (

Figure 4). In contrast to drought, the asymptomatic infection led to significant increases in the levels of all three hormones ABA, SA, and JA, and in particular to a larger relative increase in the levels of JA, which altered the relative balance between the three hormones (

Figure 8). Interestingly also, when infection and drought combined, their separate effects on the three hormones studied were clearly cumulative (

Figure 8).

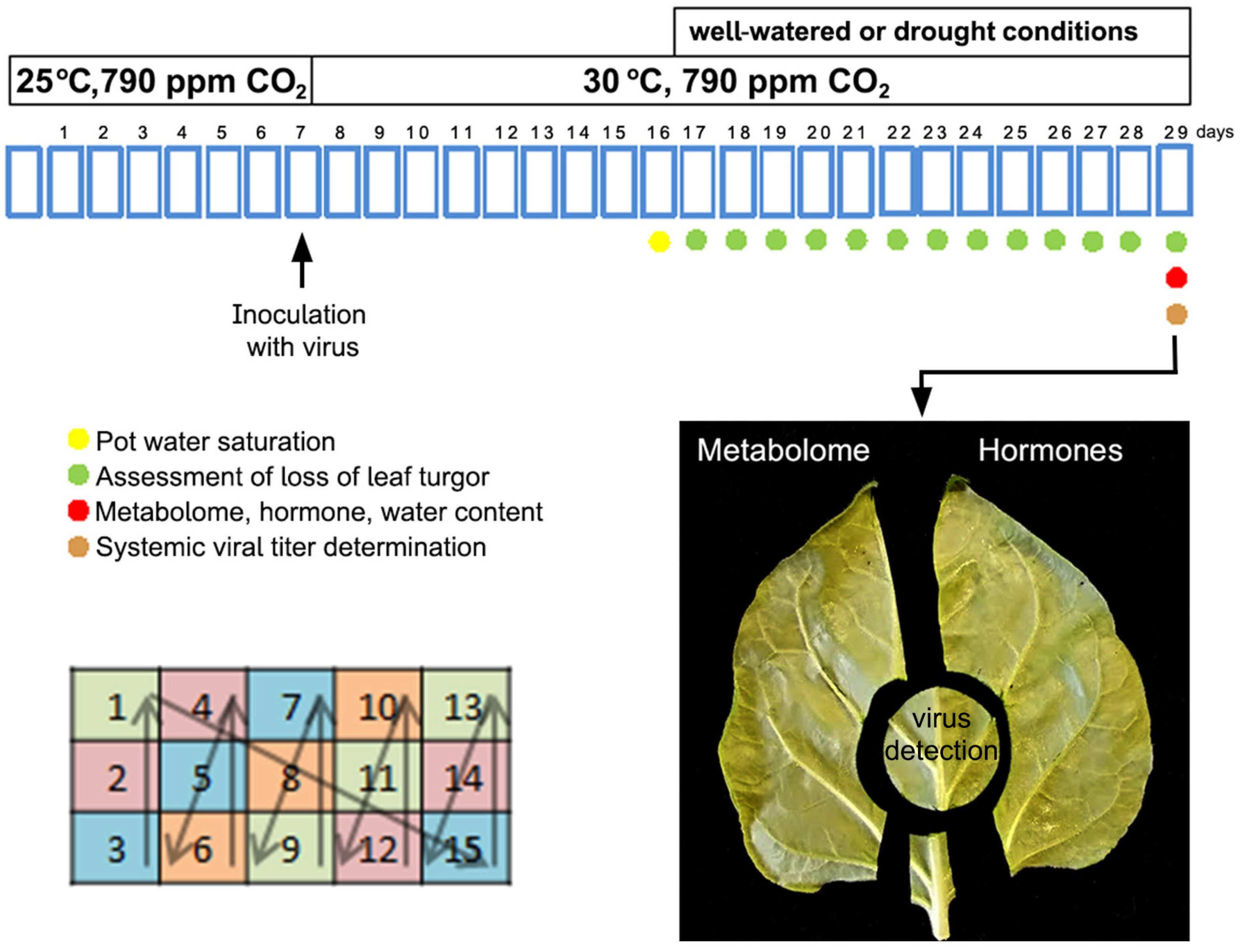

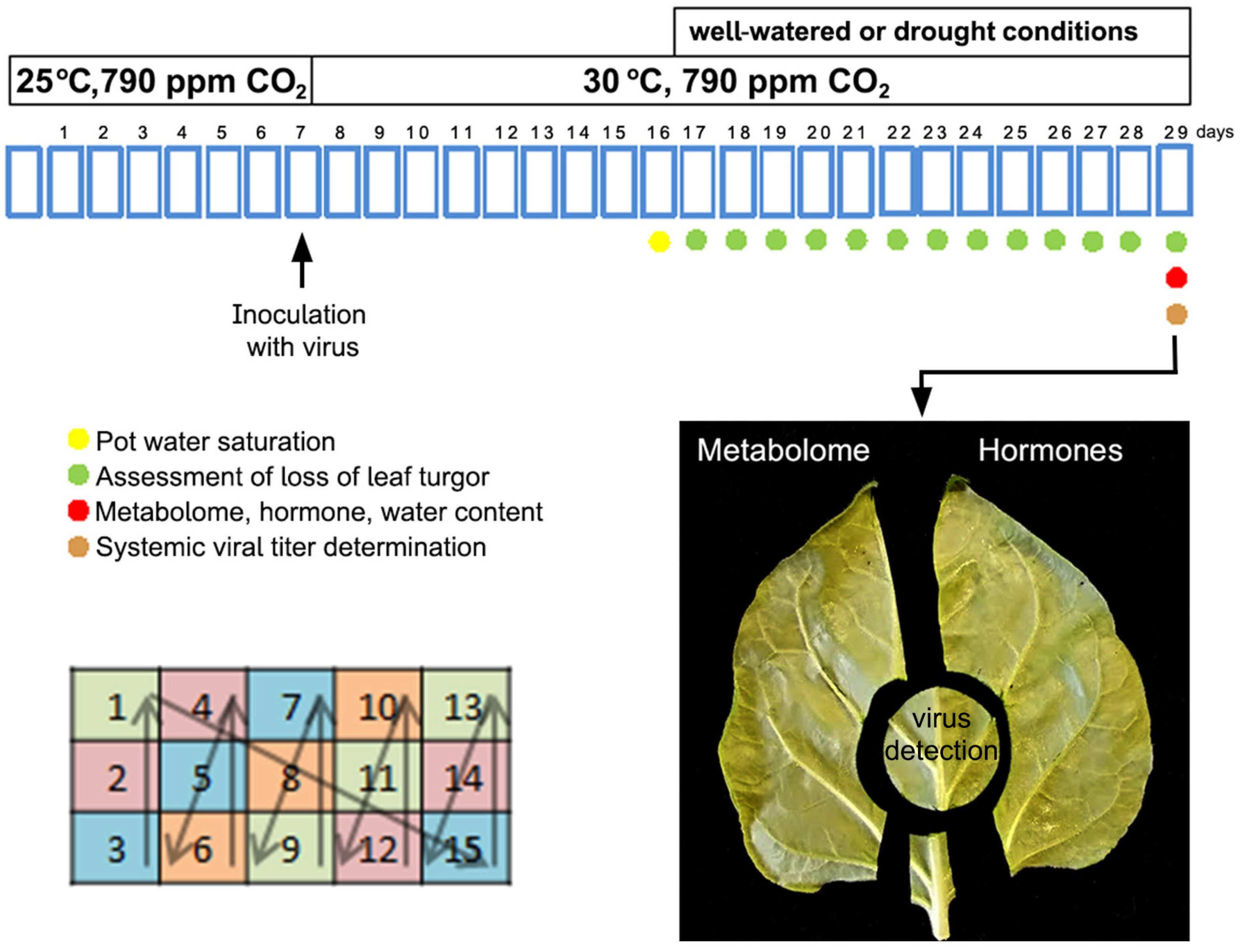

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the conditions of plant growth, the timing of virus inoculation, the start of watering withdrawal, and the type of leaf tissue sampled, for the different analyses performed. Plants (total of 60 Nicotiana benthamiana plants, organized in four trays, with 15 plants in each) were kept at 25 °C and 970 ppm of CO2 for 7 days after potting. On day 7, 30 plants were inoculated with PVY and the other 30 were mock-inoculated, and temperature was increased to 30 °C. On day 16, pots were saturated with water and from that day onwards, plants were either watered normally or not at all (watering withdrawal, drought conditions). There were therefore four types of treatment (uninfected/well-watered; uninfected/drought; infected/well-watered; infected/drought), each with 15 plants. The experiment finished 22 days after virus inoculation. Time points at which samples were taken for the analyses indicated. The lower square diagram to the left describes how the 15 plants inside each tray were moved daily, to minimize any locational effects on the measures taken. The four trays also rotated position daily.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the conditions of plant growth, the timing of virus inoculation, the start of watering withdrawal, and the type of leaf tissue sampled, for the different analyses performed. Plants (total of 60 Nicotiana benthamiana plants, organized in four trays, with 15 plants in each) were kept at 25 °C and 970 ppm of CO2 for 7 days after potting. On day 7, 30 plants were inoculated with PVY and the other 30 were mock-inoculated, and temperature was increased to 30 °C. On day 16, pots were saturated with water and from that day onwards, plants were either watered normally or not at all (watering withdrawal, drought conditions). There were therefore four types of treatment (uninfected/well-watered; uninfected/drought; infected/well-watered; infected/drought), each with 15 plants. The experiment finished 22 days after virus inoculation. Time points at which samples were taken for the analyses indicated. The lower square diagram to the left describes how the 15 plants inside each tray were moved daily, to minimize any locational effects on the measures taken. The four trays also rotated position daily.

Figure 2.

The effects on visual infection symptoms and on viral titers of an infection by PVY of Nicotiana benthamiana plants under 30 °C and 790 ppm CO2 ambient conditions. (A), No visual differences with uninfected plants were apparent. Each panel shows upper and lateral views of a plant. Plants were kept either under conditions of 25 °C and ambient (~ 410 ppm) CO2 (two panels to the left), or 30 °C and 790 ppm CO2 (two panels to the right). The upper panels show uninfected plants, and the lower panels PVY-infected plants. Images were taken two weeks after inoculation. (B), infected, well-watered plants (IW) and infected plants subject to drought (ID) held comparable viral titers at 22 days post inoculation, 13 days after watering withdrawal in the case of plants under drought conditions. Plants labeled L, M, and S correspond to larger, medium and smaller plants, respectively. Titers were several-fold lower than those found in plants kept at 25 °C and ambient CO2 levels (arbitrary value of 1). Ns indicates not significant differences at P < 0.05. Anova.

Figure 2.

The effects on visual infection symptoms and on viral titers of an infection by PVY of Nicotiana benthamiana plants under 30 °C and 790 ppm CO2 ambient conditions. (A), No visual differences with uninfected plants were apparent. Each panel shows upper and lateral views of a plant. Plants were kept either under conditions of 25 °C and ambient (~ 410 ppm) CO2 (two panels to the left), or 30 °C and 790 ppm CO2 (two panels to the right). The upper panels show uninfected plants, and the lower panels PVY-infected plants. Images were taken two weeks after inoculation. (B), infected, well-watered plants (IW) and infected plants subject to drought (ID) held comparable viral titers at 22 days post inoculation, 13 days after watering withdrawal in the case of plants under drought conditions. Plants labeled L, M, and S correspond to larger, medium and smaller plants, respectively. Titers were several-fold lower than those found in plants kept at 25 °C and ambient CO2 levels (arbitrary value of 1). Ns indicates not significant differences at P < 0.05. Anova.

Figure 3.

The effect of PVY infection on the progressive loss of leaf turgor in Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2 under drought conditions. The three charts display the loss-of-leaf turgor progression of mock vs. infected plants during drought (mock/drought, MD vs. infected/drought, ID) in three separate experiments. Individual plants were assessed daily for signs of leaf wilting. In each experiment, of 30 plants subject to watering withdrawal (drought), 15 were uninfected and 15 were infected with PVY. Wilting appeared first in the lowest leaves, and progresses upwards. Plants without signs of wilting were given the value of 0,0. If any leaf in the lower quartile of the plant displayed any sign of wilting the plant was given the value 0.25; if wilting progressed to leaves of the middle and upper middle quartiles they were given the values 0.5 and 0.75, respectively; and 1 if wilting appeared in leaves of the top quartile (the upper part) of the plant. A schematic representation of those plant quartiles is shown to the right of the upper chart. Each data point shows the average value for the plants tested. Although in the three experiments point biserial correlation tests indicated weak negative correlation between loss of turgor and infection, none were statistically significant. .

Figure 3.

The effect of PVY infection on the progressive loss of leaf turgor in Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2 under drought conditions. The three charts display the loss-of-leaf turgor progression of mock vs. infected plants during drought (mock/drought, MD vs. infected/drought, ID) in three separate experiments. Individual plants were assessed daily for signs of leaf wilting. In each experiment, of 30 plants subject to watering withdrawal (drought), 15 were uninfected and 15 were infected with PVY. Wilting appeared first in the lowest leaves, and progresses upwards. Plants without signs of wilting were given the value of 0,0. If any leaf in the lower quartile of the plant displayed any sign of wilting the plant was given the value 0.25; if wilting progressed to leaves of the middle and upper middle quartiles they were given the values 0.5 and 0.75, respectively; and 1 if wilting appeared in leaves of the top quartile (the upper part) of the plant. A schematic representation of those plant quartiles is shown to the right of the upper chart. Each data point shows the average value for the plants tested. Although in the three experiments point biserial correlation tests indicated weak negative correlation between loss of turgor and infection, none were statistically significant. .

Figure 4.

The effect of a PVY infection on the water content of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. Water content was assessed at the end of three experiments [13, 9, and 9 days after watering withdrawal (daww), respectively]. Water content in plants was significantly affected by drought in the three experiments, but not by infection in experiments 1 and 2. In experiment 3 by contrast, the loss of water content was not significant. MW, mock/watered; IW, infected/watered; MD, mock/drought; ID, infected/drought. Different letters in the charts indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Post-Hoc, Tukey.

Figure 4.

The effect of a PVY infection on the water content of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. Water content was assessed at the end of three experiments [13, 9, and 9 days after watering withdrawal (daww), respectively]. Water content in plants was significantly affected by drought in the three experiments, but not by infection in experiments 1 and 2. In experiment 3 by contrast, the loss of water content was not significant. MW, mock/watered; IW, infected/watered; MD, mock/drought; ID, infected/drought. Different letters in the charts indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Post-Hoc, Tukey.

Figure 5.

The effect of a PVY infection and of drought on stomatal conductance in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. Measures of stomatal conductance in two experiments (upper and lower charts, respectively) were taken at two time points: on day 1 after watering withdrawal (daww), and at the end of experiment (13 and 9 daww, respectively). In both experiments, at the early measurement time (absence of drought) infection reduced significantly stomatal conductance, but this was always the case at the later measurement time. Drought (later measurement time) reduced conductance significantly in all cases. MW, mock/watered; IW, infected/watered; MD, mock/drought; ID, infected/drought. Different letters in the charts indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Post-Hoc, Tukey. ** in the charts indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Student t-test.

Figure 5.

The effect of a PVY infection and of drought on stomatal conductance in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. Measures of stomatal conductance in two experiments (upper and lower charts, respectively) were taken at two time points: on day 1 after watering withdrawal (daww), and at the end of experiment (13 and 9 daww, respectively). In both experiments, at the early measurement time (absence of drought) infection reduced significantly stomatal conductance, but this was always the case at the later measurement time. Drought (later measurement time) reduced conductance significantly in all cases. MW, mock/watered; IW, infected/watered; MD, mock/drought; ID, infected/drought. Different letters in the charts indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Post-Hoc, Tukey. ** in the charts indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Student t-test.

Figure 6.

The effects of PVY infection, of drought, or of both combined, on the metabolome of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. (A), The chart shows changes in the individual levels of 53 compounds present in fresh leaf tissues from plants kept under each of the four separate treatments (MW, mock/watered; MD, IW, infected/watered; mock/drought; ID, infected/drought). Their levels were relativized to those found in the MW plants, with the average values from the eight MW plants given the arbitrary value of 1. (B), The charts detail the accumulation of the sugar fructose (left chart), and of the amino acid proline (right chart) in the four types of plants. Different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Post Hoc, Tukey.

Figure 6.

The effects of PVY infection, of drought, or of both combined, on the metabolome of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. (A), The chart shows changes in the individual levels of 53 compounds present in fresh leaf tissues from plants kept under each of the four separate treatments (MW, mock/watered; MD, IW, infected/watered; mock/drought; ID, infected/drought). Their levels were relativized to those found in the MW plants, with the average values from the eight MW plants given the arbitrary value of 1. (B), The charts detail the accumulation of the sugar fructose (left chart), and of the amino acid proline (right chart) in the four types of plants. Different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Post Hoc, Tukey.

Figure 7.

The effects of PVY infection, of drought, or of both combined, on the metabolome of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. (A), Hierarchical cluster dendrogram of the metabolic data for the four separating treatments combinations (mock/watered, MW; infected/watered, IW; mock/drought, MD; infected/drought, ID) as mean values of 53 compounds. Hierarchical clustering was performed using R package. (B), principal component analysis (PCA) to sort the 53-component metabolome analysis in each of the four types of samples analyzed (MW, in blue; IW, in red; MD, in brown; ID, in green). The two principal components explained 70.25% of the overall variance of metabolite profiles: 51.42% for principal component 1 (PC1) and 18.82% principal component 2 (PC2). Together with PC3 (8.94%) they explain 79.19% of the variance. Each individual biological replicate is represented in the score plots.

Figure 7.

The effects of PVY infection, of drought, or of both combined, on the metabolome of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. (A), Hierarchical cluster dendrogram of the metabolic data for the four separating treatments combinations (mock/watered, MW; infected/watered, IW; mock/drought, MD; infected/drought, ID) as mean values of 53 compounds. Hierarchical clustering was performed using R package. (B), principal component analysis (PCA) to sort the 53-component metabolome analysis in each of the four types of samples analyzed (MW, in blue; IW, in red; MD, in brown; ID, in green). The two principal components explained 70.25% of the overall variance of metabolite profiles: 51.42% for principal component 1 (PC1) and 18.82% principal component 2 (PC2). Together with PC3 (8.94%) they explain 79.19% of the variance. Each individual biological replicate is represented in the score plots.

Figure 8.

The effects of PVY infection, of drought, or of both combined, on the hormone levels of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. The levels of three hormones (abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) were quantified in four types of plants: mock/watered, MW; infected/watered, IW; mock/drought, MD; infected/drought, ID. Infected plants were assessed 22 days after inoculation, and those plants subjected to drought had been the last 13 days without watering. Infection significantly increased the levels of the three hormones. Drought only those of ABA. The increase in JA levels caused by infection was differentially higher, and led to two types of hormone profiles (MW and MD vs. IW and ID), defined by the presence/absence of infection. Within the same color, different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Post Hoc, Tukey.

Figure 8.

The effects of PVY infection, of drought, or of both combined, on the hormone levels of Nicotiana benthamiana plants grown at 30 °C and 790 ppm ambient CO2. The levels of three hormones (abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) were quantified in four types of plants: mock/watered, MW; infected/watered, IW; mock/drought, MD; infected/drought, ID. Infected plants were assessed 22 days after inoculation, and those plants subjected to drought had been the last 13 days without watering. Infection significantly increased the levels of the three hormones. Drought only those of ABA. The increase in JA levels caused by infection was differentially higher, and led to two types of hormone profiles (MW and MD vs. IW and ID), defined by the presence/absence of infection. Within the same color, different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05. Post Hoc, Tukey.