Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

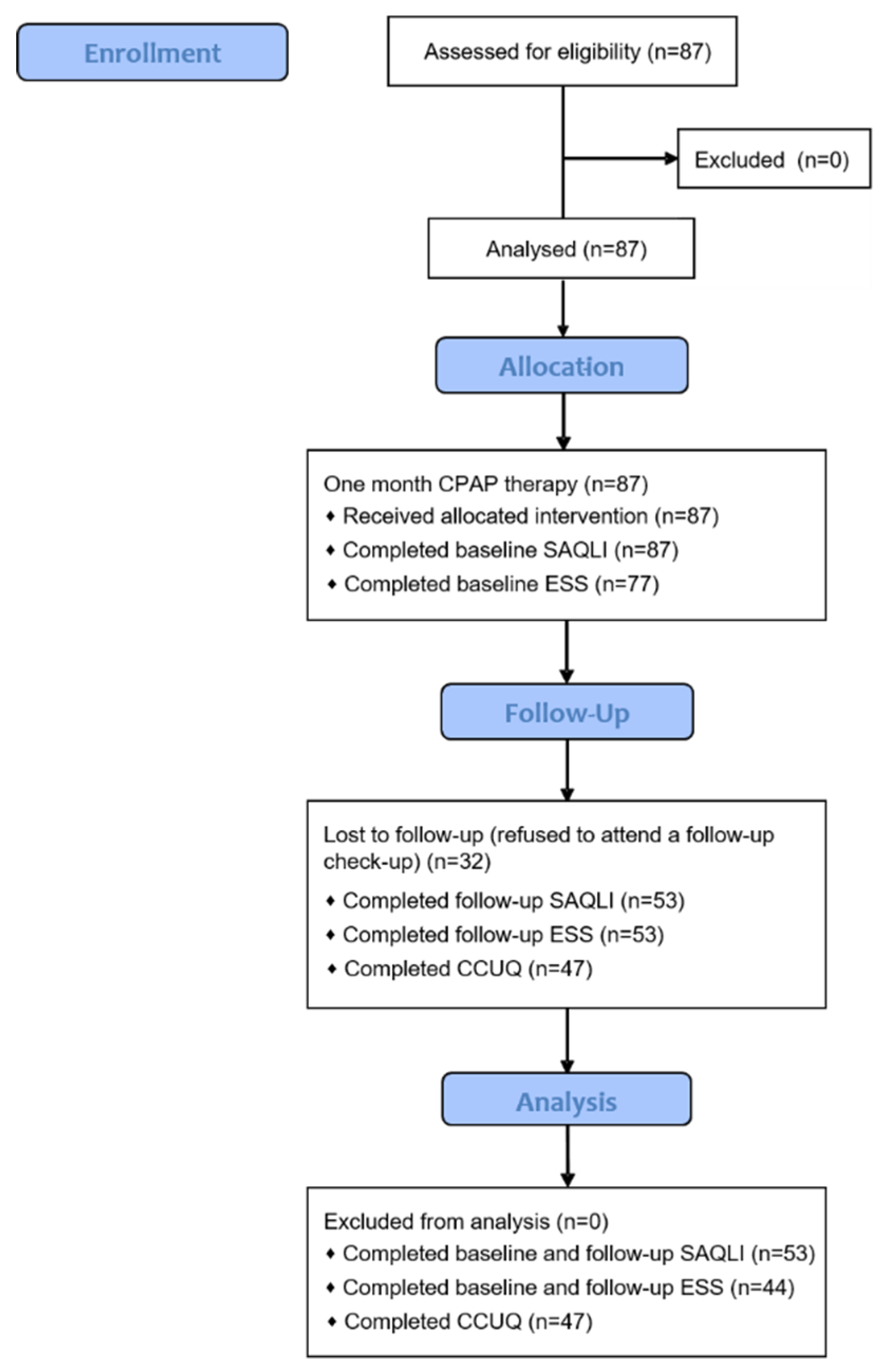

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Patients

2.3. Questionnaires

2.4. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, Heinzer R, Ip MSM, Morrell MJ, Nunez CM, Patel SR, Penzel T, Pépin JL, Peppard PE, Sinha S, Tufik S, Valentine K, Malhotra A. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2019, 7(8), 687-98. [CrossRef]

- Stradling J. Obstructive sleep apnoea. BMJ. 2007, 335(7615), 313-4. [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, E.M.; Nadeem, R.; Nida, M.; Molnar, J.; Aggarwal, S.; Loomba, R. The Role of Severity of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Measured by Apnea–Hypopnea Index in Predicting Compliance With Pressure Therapy, a Meta-analysis. Am. J. Ther. 2014, 21, 260–264. [CrossRef]

- West SD, Turnbull C. Obstructive sleep apnoea. Eye (Lond). 2018, 32(5), 889-903. [CrossRef]

- Rapelli, G.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Bastoni, I.; Scarpina, F.; Tovaglieri, I.; Perger, E.; Garbarino, S.; Fanari, P.; Lombardi, C.; et al. Improving CPAP Adherence in Adults With Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: A Scoping Review of Motivational Interventions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shou, X.; Wu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Cui, J.; Zhuang, R.; Luo, R. Relationships Between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Bibliometric Analysis (2010-2021). Med Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e933448–e933448-12. [CrossRef]

- Labarca G, Saavedra D, Dreyse J, Jorquera J, Barbe F. Efficacy of CPAP for Improvements in Sleepiness, Cognition, Mood, and Quality of Life in Elderly Patients With OSA: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Chest. 2020, 158(2), 751-64. [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. JAMA. 2020, 323(14), 1389-400. [CrossRef]

- Labarca, G.; Schmidt, A.; Dreyse, J.; Jorquera, J.; Enos, D.; Torres, G.; Barbe, F. Efficacy of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and resistant hypertension (RH): Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 58, 101446. [CrossRef]

- Zinchuk, A.V.; Gentry, M.J.; Concato, J.; Yaggi, H.K. Phenotypes in obstructive sleep apnea: A definition, examples and evolution of approaches. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 35, 113–123. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.A.; Simpson, F.C. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Psychiatric Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 165–175. [CrossRef]

- Pecotic, R.; Dodig, I.P.; Valic, M.; Galic, T.; Kalcina, L.L.; Ivkovic, N.; Dogas, Z. Effects of CPAP therapy on cognitive and psychomotor performances in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective 1-year study. Sleep Breath. 2018, 23, 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Batool-Anwar, S.; Goodwin, J.L.; Kushida, C.A.; Walsh, J.A.; Simon, R.D.; Nichols, D.A.; Quan, S.F. Impact of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) on quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). J. Sleep Res. 2016, 25, 731–738. [CrossRef]

- Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016, 34(7), 645-9. [CrossRef]

- Haraldstad K, Wahl A, Andenæs R, Andersen JR, Andersen MH, Beisland E, Borge CR, Engebretsen E, Eisemann M, Halvorsrud L, Hanssen TA, Haugstvedt A, Haugland T, Johansen VA, Larsen MH, Løvereide L, Løyland B, Kvarme LG, Moons P, Norekvål TM, Ribu L, Rohde GE, Urstad KH, Helseth S; LIVSFORSK network. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. 2019, 28(10), 2641-50. [CrossRef]

- Flemons, W.W.; Reimer, M.A. Measurement Properties of the Calgary Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn E, Schwarz EI, Bratton DJ, Rossi VA, Kohler M. Effects of CPAP and Mandibular Advancement Devices on Health-Related Quality of Life in OSA: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2017, 151(4), 786-94. [CrossRef]

- Bakker JP, Weaver TE, Parthasarathy S, Aloia MS. Adherence to CPAP: What Should We Be Aiming For, and How Can We Get There? Chest. 2019, 155(6), 1272-87. [CrossRef]

- Battan G, Kumar S, Panwar A, Atam V, Kumar P, Gangwar A, Roy U. Effect of CPAP Therapy in Improving Daytime Sleepiness in Indian Patients with Moderate and Severe OSA. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(11):OC14-OC16. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013, 310(20), 2191-4.

- Pecotic, R.; Dodig, I.P.; Valic, M.; Ivkovic, N.; Dogas, Z. The evaluation of the Croatian version of the Epworth sleepiness scale and STOP questionnaire as screening tools for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath. 2011, 16, 793–802. [CrossRef]

- A Walker, N.; Sunderram, J.; Zhang, P.; Lu, S.-E.; Scharf, M.T. Clinical utility of the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 1759–1765. [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. A New Method for Measuring Daytime Sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [CrossRef]

- Flemons, W.W.; Reimer, M.A. Development of a Disease-specific Health-related Quality of Life Questionnaire for Sleep Apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 158, 494–503. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.; Smith, S.; Oei, T.P.S.; Douglas, J. Cues to starting CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea: development and validation of the cues to CPAP Use Questionnaire. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2010, 6, 229–37. [CrossRef]

- AASM International Classification of Sleep Disorders—Third Edition (ICSD-3) [(accessed on 25 March 2023)]. Available online: https://learn.aasm.org/Listing/a1341000002XmRvAAK.

- Kim, T. Quality of Life in Metabolic Syndrome Patients Based on the Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 127. [CrossRef]

- Lee W, Lee SA, Ryu HU, Chung YS, Kim WS. Quality of life in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: Relationship with daytime sleepiness, sleep quality, depression, and apnea severity. Chron Respir Dis. 2016, 13(1), 33-9. [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S.; Togawa, J.; Sunadome, H.; Nagasaki, T.; Takahashi, N.; Hirai, T.; Sato, S. Sleep Restfulness in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea Undergoing Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy. Sleep Sci. 2024, 17, e37–e44. [CrossRef]

- Sgaria, V.P.; Cielo, C.A.; Bortagarai, F.M.; Fleig, A.H.D.; Callegaro, C.C. CPAP Treatment Improves Quality of Life and Self-perception of Voice Impairment in Patients with OSA. J. Voice 2024. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Bhat, A.; Saroya, J.; Chang, J.; Durr, M.L. Sociodemographic and Healthcare System Barriers to PAP Alternatives for Adult OSA: A Scoping Review. Laryngoscope 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chang, Y.-F.; Wang, Y.-F.; Xie, Q.-X.; Ran, X.-Z.; Hu, C.-Y.; Luo, B.; Ning, B. Effect of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure on Blood Pressure in Patients with Resistant Hypertension and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Updated Meta-analysis. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2024, 26, 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Ala, M.; Amali, A.; Hivechi, N.; Heidari, R.; Mokary, Y. An Evaluation of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patient’s Quality of life Following Continuous Positive Airway Pressure and Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 76, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Yeghiazarians Y, Jneid H, Tietjens JR, Redline S, Brown DL, El-Sherif N, Mehra R, Bozkurt B, Ndumele CE, Somers VK. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021, 144(3), e56-e67. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, T.E.; Grunstein, R.R. Adherence to Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy: The Challenge to Effective Treatment. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2008, 5, 173–178. [CrossRef]

- Franke, C.; Piezonna, F.; Schäfer, R.; Grimm, A.; Loris, L.-M.; Schwaibold, M. Effect of a digital patient motivation and support tool on CPAP/APAP adherence and daytime sleepiness: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2023, 22, 49–63. [CrossRef]

- Schisano, M.; Libra, A.; Rizzo, L.; Morana, G.; Mancuso, S.; Ficili, A.; Campagna, D.; Vancheri, C.; Bonsignore, M.R.; Spicuzza, L. Distance follow-up by a remote medical care centre improves adherence to CPAP in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea over the short and long term. J. Telemed. Telecare 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gabryelska, A.; Sochal, M.; Wasik, B.; Szczepanowski, P.; Białasiewicz, P. Factors Affecting Long-Term Compliance of CPAP Treatment—A Single Centre Experience. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 11, 139. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.-E.; Jung, J.H.; Kang, J.M.; Cho, M.Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Kang, S.-G.; Kim, S.T. Predictors of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Adherence and Comparison of Clinical Factors and Polysomnography Findings Between Compliant and Non-Compliant Korean Adults With Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Psychiatry Investig. 2024, 21, 200–207. [CrossRef]

- Kasetti, P.; Husain, N.; Skinner, T.; Asimakopoulou, K.; Steier, J.; Sathyapala, S. Personality traits and pre-treatment beliefs and cognitions predicting patient adherence to continuous positive airway pressure: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2024, 74, 101910. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S.; Saito, A.; Sasaki, F.; Hayashi, M.; Mieno, Y.; Sakakibara, H.; Hashimoto, S. Associations of self-efficacy and outcome expectancy with adherence to continuous positive airway pressure therapy in Japanese patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Fujita Med. J. 2022, 9, 142–146. [CrossRef]

- Laratta, C.R.; Ayas, N.T.; Povitz, M.; Pendharkar, S.R. Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2017, 189, E1481–E1488. [CrossRef]

- Bailly, S.; Grote, L.; Hedner, J.; Schiza, S.; McNicholas, W.T.; Basoglu, O.K.; Lombardi, C.; Dogas, Z.; Roisman, G.; Pataka, A.; et al. Clusters of sleep apnoea phenotypes: A large pan-European study from the European Sleep Apnoea Database (ESADA). Respirology 2020, 26, 378–387. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Total patients (n=87) |

|---|---|

| Age | 55.6±12.5 |

| Gender | |

| Men | 67 (77) |

| Women | 20 (23) |

| Height (cm) | 179.3±9.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 108.9±24.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 33.2±7.4 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 45.4±5.0 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 118.0±16.0 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 115.6±12.4 |

| Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) | 50.5±19.1 |

| Oxygen Desaturation Index (ODI) | 51.0±22.8 |

| Mean saturation (%) | 92.8±3.6 |

| Time below 90% saturation (min) | 80.1±109.2 |

| Lowest saturation (%) | 72.3±11.8 |

| Parameters | Total (n=55) | CPAP non-compliant (n=21) | CPAP compliant (n=34) | p† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average usage (all days, min)* | 305.3±116.5 | 193.6±71.5 | 378.6±74 | <0.001 |

| Average usage (days used, min)* | 341.2±99.9 | 255.3±73.5 | 397.6±70.5 | <0.001 |

| Total days with device usage (n)* | 26.8±7.4 | 23.6±10.3 | 28.8±3.5 | 0.011 |

| Percentage of days with device usage* | 88%±17.8% | 78.3%±23.1% | 94.4%±9% | <0.001 |

| Total days with CPAP usage ≥4h | 20.5±9.3 | 10.7±5.8 | 26.5±4.8 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of days with CPAP usage ≥4h | 69.8%±28.7% | 37.9%±19% | 89.4%±9.5% | <0.001 |

| Average apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) | 4.7±4.6 | 6.5±6.3 | 3.5±2.8 | 0.018 |

| Parameters | Before CPAP | After one month of CPAP | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain A | 2.9±1.2 | 2.1±1.2 | <0.001 |

| Domain B | 2.9±1.2 | 2.1±1.2 | <0.001 |

| Domain C | 2.8±1.3 | 2.2±1.1 | <0.001 |

| Domain D† | 5.2±1.7 | 3.3±1.7 | <0.001 |

| Domain E† | - | 2.8±1.5 | - |

| Total SALQI† | 3.4±1.1 | 1.7±0.9 | <0.001 |

| Domain F I† | - | 7.0±2.4 | - |

| Domain F II† | - | 3.6±3.3 | - |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale‡ | 7.2±5.1 | 4.6±4.2 | 0.004 |

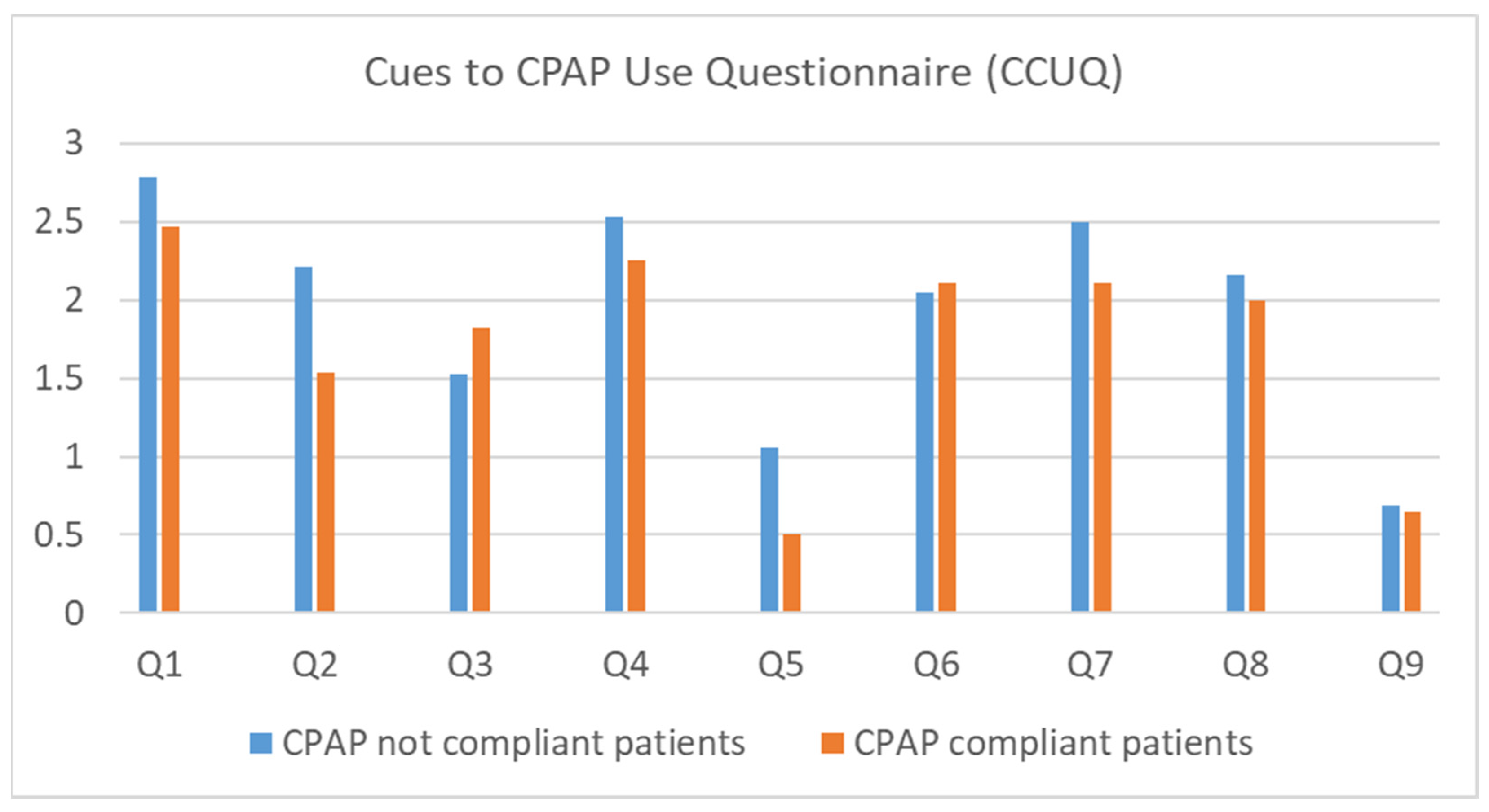

| Parameters | Total (n=50) | CPAP non-compliant (n=20) | CPAP compliant (n=30) | p* | OR (95%CI) | p† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 My sleep physician said that I should | 44 (88.0) | 19 (95.0) | 23 (76.7) | 0.214 | 0.263 (0.028-2.443) | 0.381 |

| Q2 I was worried about my heart | 30 (60.0) | 16 (80.0) | 14 (46.7) | 0.018 | 0.219 (0.059-0.810) | 0.022 |

| Q3 Partner couldn't sleep because of my snoring | 29 (58.0) | 10 (50.0) | 19 (63.3) | 0.349 | 1.727 (0.548-5.448) | 0.393 |

| Q4 My sleep physician was worried about my OSA | 42 (84.0) | 18 (90.0) | 24 (80.0) | 0.345 | 0.444 (0.080-2.465) | 0.450 |

| Q5 Advice from a friend/acquaintance (who does not have OSA) | 11 (22.0) | 7 (35.0) | 4 (13.3) | 0.070 | 0.286 (0.071-1.155) | 0.090 |

| Q6 Partner encouraged me to start CPAP† | 34 (69.4) | 14 (70.0) | 20 (69.0) | 0.938 | 0.952 (0.276-3.286) | 1.000 |

| Q7 I was worried about the health consequences of my sleep problem | 39 (78.0) | 17 (85.0) | 22 (73.3) | 0.329 | 0.485 (0.112-2.111) | 0.489 |

| Q8 I was so tired all of the time | 36 (72.0) | 16 (80.0) | 20 (66.7) | 0.304 | 0.500 (0.132-1.896) | 0.353 |

| Q9 I was worried that I would have a car accident | 10 (20.0) | 5 (25.0) | 5 (16.7) | 0.470 | 0.600 (0.149-0.421) | 0.494 |

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficients | Standard Error | Standardized coefficients | T | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apnea-hypopnea index* | -0.342 | 0.990 | -0.051 | -0.345 | 0.732 |

| Epworth sleepiness scale* | -8.653 | 3.684 | -0.387 | -2.349 | 0.024 |

| Total SALQI score* | 48.263 | 16.647 | 0.481 | 2.899 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).