Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Humoral Immune Response Assays

2.3. Cellular Immune Response Assay

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristic of Study Participants

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, months [median (minimum–maximum)] | 92 (81–103) |

| BMI, kg/m2 [median (minimum–maximum)] | 14.8 (12.3–19.7) |

| Sex [n (%)] Male Female |

60 (39) 94 (61) |

| Parental occupation [n (%)] Working Not working |

71 (46.1) 83 (53.9) |

| Parental income [n (%)] Equal or above the minimum wage Below the minimum wage |

24 (15.6) 130 (84.4) |

| History of acute respiratory infection in last 6 months [n (%)] < 3 times ≥ 3 times |

106 (68.8) 48 (31.2) |

| History of COVID-19 disease in other family members [n (%)] No Yes |

73 (47.4) 81 (52.6) |

| Classification based on both vaccination statuses [n (%)] Group A (COVID-19 yes / DTP yes) Group B (COVID-19 yes / DTP no) Group C (COVID-19 no / DTP yes) Group D (COVID-19 no / DTP no) |

39 (25.3) 38 (24.7) 38 (24.7) 39 (25.3) |

3.2. Titers of Anti-Diphtheria Toxoid IgG

3.3. Titers of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD Antibodies

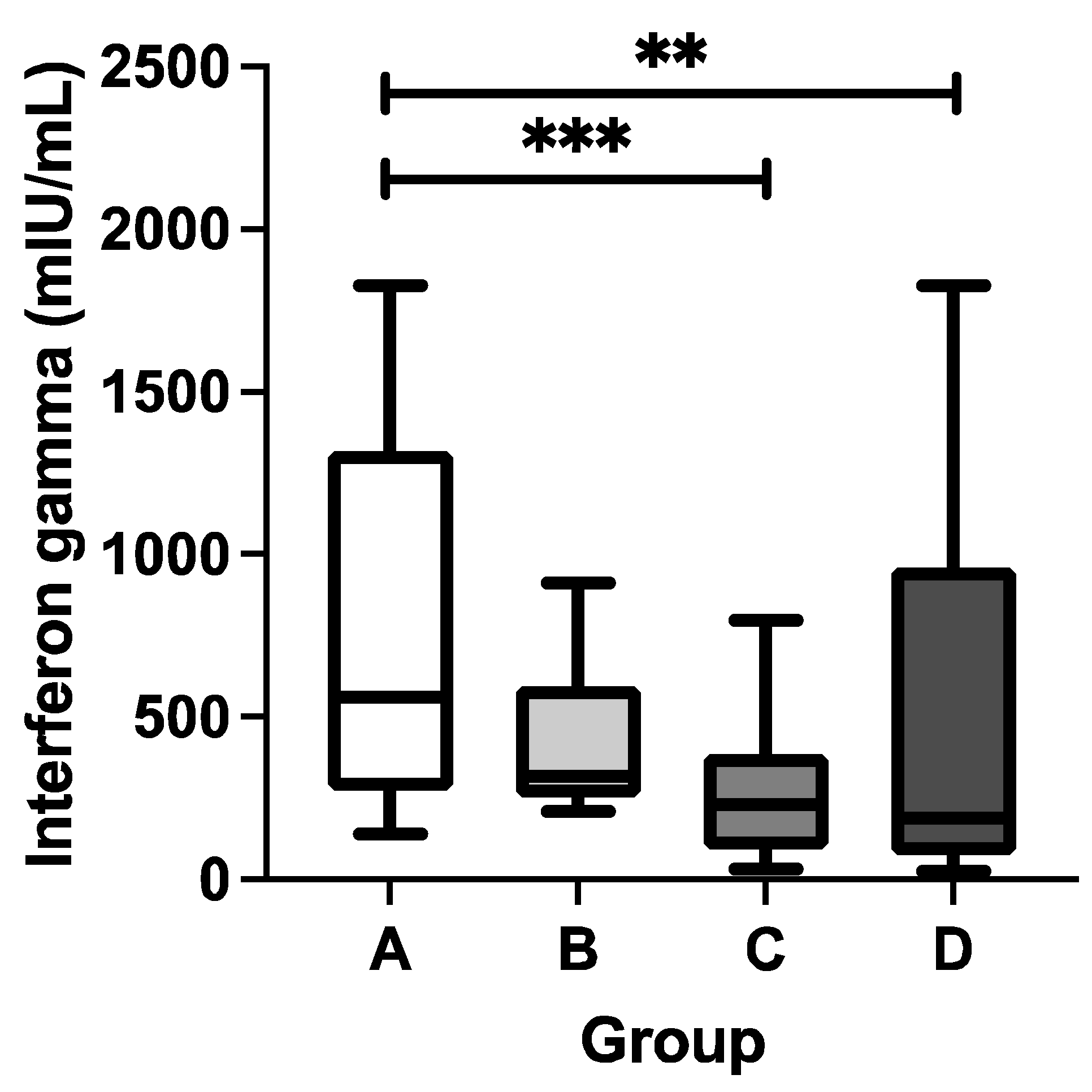

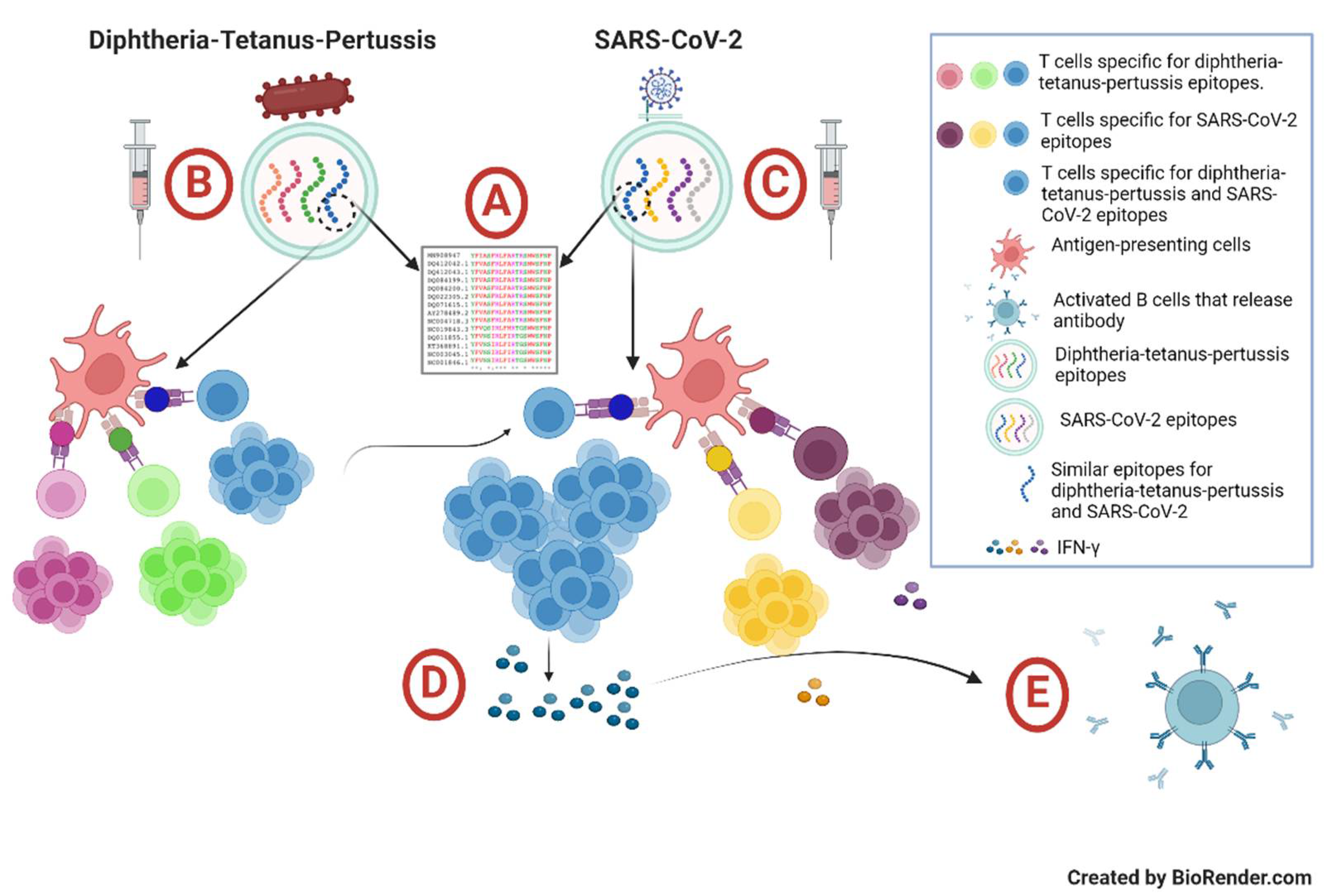

3.4. Concentrations of SARS-CoV-2-Specific T Cell-Derived IFN-g

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization WHO COVID-19 Dashboard Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Barouch, D.H. Covid-19 Vaccines — Immunity, Variants, Boosters. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1011–1020. [CrossRef]

- Tatar, M.; Shoorekchali, J.M.; Faraji, M.R.; Seyyedkolaee, M.A.; Pagán, J.A.; Wilson, F.A. COVID-19 Vaccine Inequality: A Global Perspective. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 10–13. [CrossRef]

- Gozzi, N.; Chinazzi, M.; Dean, N.E.; Longini, I.M.; Halloran, M.E.; Perra, N.; Vespignani, A. Estimating the Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine Inequities: A Modeling Study. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Steinman, J.B.; Lum, F.M.; Ho, P.P.K.; Kaminski, N.; Steinman, L. Reduced Development of COVID-19 in Children Reveals Molecular Checkpoints Gating Pathogenesis Illuminating Potential Therapeutics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 24620–24626. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. Why Is COVID-19 Less Severe in Children? A Review of the Proposed Mechanisms Underlying the Age-Related Difference in Severity of SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 429–439. [CrossRef]

- Axfors, C.; Pezzullo, A.M.; Contopoulos-Ioannidis, D.G.; Apostolatos, A.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Differential COVID-19 Infection Rates in Children, Adults, and Elderly: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 38 Pre-Vaccination National Seroprevalence Studies. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.A.; Dowell, A.C.; Moss, P.; Ladhani, S.N. Current State of COVID-19 in Children: 4 Years On. J. Infect. 2024, 88. [CrossRef]

- Munro, A.P.S.; Jones, C.E.; Faust, S.N. Vaccination against COVID-19 — Risks and Benefits in Children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 1107–1112. [CrossRef]

- Castagnoli, R.; Votto, M.; Licari, A.; Brambilla, I.; Bruno, R.; Perlini, S.; Rovida, F.; Baldanti, F.; Marseglia, G.L. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 882–889. [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, L.R.; Rose, E.B.; Horwitz, S.M.; Collins, J.P.; Newhams, M.M.; Son, M.B.F.; Newburger, J.W.; Kleinman, L.C.; Heidemann, S.M.; Martin, A.A.; et al. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in U.S. Children and Adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 334–346. [CrossRef]

- Hoste, L.; Paemel, R. Van; Haerynck, F. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Related to COVID-19: A Systematic Review.Eur J Pediatr.2021, Jul;180(7):2019-2034. [CrossRef]

- Pudjiadi, A.H.; Putri, N.D.; Sjakti, H.A.; Yanuarso, P.B.; Gunardi, H.; Roeslani, R.D.; Pasaribu, A.D.; Nurmalia, L.D.; Sambo, C.M.; Ugrasena, I.D.G.; et al. Pediatric COVID-19: Report From Indonesian Pediatric Society Data Registry. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Nachega, J.B.; Sam-Agudu, N.A.; MacHekano, R.N.; Rabie, H.; Van Der Zalm, M.M.; Redfern, A.; Dramowski, A.; O’Connell, N.; Pipo, M.T.; Tshilanda, M.B.; et al. Assessment of Clinical Outcomes among Children and Adolescents Hospitalized with COVID-19 in 6 Sub-Saharan African Countries. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, E216436. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Prado, E.; Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Fernandez-Naranjo, R.; Vasconez, J.; Dávila Rosero, M.G.; Revelo-Bastidas, D.; Herrería-Quiñonez, D.; Rubio-Neira, M. The Deadly Impact of COVID-19 among Children from Latin America: The Case of Ecuador. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Valdez, L.; Richardson, V.L.; Bautista-Márquez, A.; Camacho Franco, M.A.; Cruz Cruz, V.; Hernández Ávila, M. Three Years of COVID-19 in Children That Attend the Mexican Social Security Institute’s 1,350 Child Day-Care Centers, 2020–2023. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, D.; Ismail, N.F.; Zhu, F.; Wang, X.; del Carmen Morales, G.; Srivastava, A.; Allen, K.E.; Spinardi, J.; Rahman, A.E.; Kyaw, M.H.; et al. Epidemiology and Clinical Features of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Children and Adolescents in the Pre-Omicron Era: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Boucau, J.; Regan, J.; Choudhary, M.C.; Burns, M.D.; Young, N.; Farkas, E.J.; Davis, J.P.; Moschovis, P.P.; Bernard Kinane, T.; et al. Virologic Features of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection in Children. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, 1821–1829. [CrossRef]

- Hartantri, Y.; Debora, J.; Widyatmoko, L.; Giwangkancana, G.; Suryadinata, H.; Susandi, E.; Hutajulu, E.; Hakiman, A.P.A.; Pusparini, Y.; Alisjahbana, B. Clinical and Treatment Factors Associated with the Mortality of COVID-19 Patients Admitted to a Referral Hospital in Indonesia. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Southeast Asia 2023, 11, 100167. [CrossRef]

- Santi, T.; Hegar, B.; Munasir, Z.; Prayitno, A.; Werdhani, R.A.; Bandar, I.N.S.; Jo, J.; Uswa, R.; Widia, R.; Vandenplas, Y. Factors Associated with Parental Intention to Vaccinate Their Preschool Children against COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Urban Area of Jakarta, Indonesia. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2023, 12, 240–248. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia Vaksinasi COVID-19 Nasional.

- Widianto, S. Indonesia to Start Vaccinating Children Aged 6-11 against COVID-19 Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/indonesia-start-vaccinating-children-aged-6-11-against-covid-19-2021-12-13/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Suhenda, D. COVID-19 Vaccine Shortages Reported across Country Available online: https://www.thejakartapost.com/indonesia/2022/10/21/covid-19-vaccine-shortages-reported-across-country.html (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Messina, N.L.; Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. The Impact of Vaccines on Heterologous Adaptive Immunity. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 1484–1493. [CrossRef]

- Reche, P.A. Potential Cross-Reactive Immunity to SARS-CoV-2 From Common Human Pathogens and Vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Monereo-Sánchez, J.; Luykx, J.J.; Pinzón-Espinosa, J.; Richard, G.; Motazedi, E.; Westlye, L.T.; Andreassen, O.A.; van der Meer, D. Diphtheria And Tetanus Vaccination History Is Associated With Lower Odds of COVID-19 Hospitalization. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, L.; Adkins, E.; Karyanti, M.R.; Ong-Lim, A.; Shenoy, B.; Huoi, C.; Vargas-Zambrano, J.C. What Is the True Burden of Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis and Poliovirus in Children Aged 3–18 Years in Asia? A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 117, 116–129. [CrossRef]

- Zasada, A.A.; Rastawicki, W.; Śmietańska, K.; Rokosz, N.; Jagielski, M. Comparison of Seven Commercial Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays for the Detection of Anti-Diphtheria Toxin Antibodies. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32, 891–897. [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.; Sanjaya, A.; Pinontoan, R.; Aruan, M.; Wahyuni, R.M.; Viktaria, V. Assessment on Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain Antibodies among CoronaVac-Vaccinated Indonesian Adults. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2022, 11, 116. [CrossRef]

- Saad Albichr, I.; Mzougui, S.; Devresse, A.; Georgery, H.; Goffin, E.; Kanaan, N.; Yombi, J.C.; Belkhir, L.; De Greef, J.; Scohy, A.; et al. Evaluation of a Commercial Interferon-γ Release Assay for the Detection of SARS-CoV-2 T-Cell Response after Vaccination. Heliyon 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, E.B. Identifying and Evaluating the Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents. Ethn. Dis. 2007, 17.

- Tan, A.T.; Lim, J.M.E.; Le Bert, N.; Kunasegaran, K.; Chia, A.; Qui, M.D.C.; Tan, N.; Chia, W.N.; de Alwis, R.; Ying, D.; et al. Rapid Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 Spike T Cells in Whole Blood from Vaccinated and Naturally Infected Individuals. J. Clin. Invest. 2021, 131. [CrossRef]

- Indonesian Pediatric Society Proceeding Book Childhood Immunization Update 2023; 2023;

- Harapan, H.; Anwar, S.; Dimiati, H.; Hayati, Z.; Mudatsir, M. Diphtheria Outbreak in Indonesia, 2017: An Outbreak of an Ancient and Vaccine-Preventable Disease in the Third Millennium. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Heal. 2019, 7, 261–262. [CrossRef]

- Itiakorit, H.; Sathyamoorthi, A.; O’Brien, B.E.; Nguyen, D. COVID-19 Impact on Disparity in Childhood Immunization in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Through the Lens of Historical Pandemics. Curr. Trop. Med. Reports 2022, 9, 225–233. [CrossRef]

- Arguni, E.; Karyanti, M.R.; Satari, H.I.; Hadinegoro, S.R. Diphtheria Outbreak in Jakarta and Tangerang, Indonesia: Epidemiological and Clinical Predictor Factors for Death. PLoS One 2021, 16, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Sunarno, S.; Sofiah, S.N.; Amalia, N.; Hartoyo, Y.; Rizki, A.; Puspandari, N.; Saraswati, R.D.; Febriyana, D.; Febrianti, T.; Susanti, I.; et al. Laboratory and Epidemiology Data of Pertussis Cases and Close Contacts: A 5-Year Case-Based Surveillance of Pertussis in Indonesia, 2016–2020. PLoS One 2022, 17, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Song, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, W.; Ma, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Li, M.; Lian, X.; Jiao, W.; Wang, L.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of an Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine (CoronaVac) in Healthy Children and Adolescents: A Double-Blind, Randomised, Controlled, Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1645–1653. [CrossRef]

- Walter, E.B.; Talaat, K.R.; Sabharwal, C.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Paulsen, G.C.; Barnett, E.D.; Muñoz, F.M.; Maldonado, Y.; Pahud, B.A.; et al. Evaluation of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine in Children 5 to 11 Years of Age. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 35–46. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Wu, Q.; Pan, H.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, Z.; Jiang, D.; Deng, X.; Chu, K.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of a Third Dose of CoronaVac, and Immune Persistence of a Two-Dose Schedule, in Healthy Adults: Interim Results from Two Single-Centre, Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Clinical Trials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 483–495. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.M.E.; Hang, S.K.; Hariharaputran, S.; Chia, A.; Tan, N.; Lee, E.S.; Chng, E.; Lim, P.L.; Young, B.E.; Lye, D.C.; et al. A Comparative Characterization of SARS-CoV-2-Specific T Cells Induced by MRNA or Inactive Virus COVID-19 Vaccines. Cell Reports Med. 2022, 3, 100793. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ying, L.; Wang, J.; Xia, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, H.; Zhang, R.; Zang, R.; Le, Z.; Shu, Q.; et al. Non-Spike and Spike-Specific Memory T Cell Responses after the Third Dose of Inactivated COVID-19 Vaccine. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Bertoletti, A.; Le Bert, N.; Tan, A.T. SARS-CoV-2-Specific T Cells in the Changing Landscape of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Immunity 2022, 55, 1764–1778. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Kang, A.Y.H.; Tay, C.J.X.; Li, H.E.; Elyana, N.; Tan, C.W.; Yap, W.C.; Lim, J.M.E.; Le Bert, N.; Chan, K.R.; et al. Correlates of Protection against Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 in Vaccinated Children. Nat. Med. 2024, 30. [CrossRef]

- Santi, T.; Sungono, V.; Kamarga, L.; Samakto, B. De; Hidayat, F.; Hidayat, F.K.; Satolom, M.; Permana, A.; Yusuf, I.; Suriapranata, I.M.; et al. Heterologous Prime-Boost with the MRNA-1273 Vaccine among CoronaVac-Vaccinated Healthcare Workers in Indonesia. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2022, 11, 209–216.

- Barin, B.; Kasap, U.; Selçuk, F.; Volkan, E.; Uluçkan, Ö. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Anti-Spike Receptor Binding Domain IgG Antibody Responses after CoronaVac, BNT162b2, ChAdOx1 COVID-19 Vaccines, and a Single Booster Dose: A Prospective, Longitudinal Population-Based Study. The Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e274–e283. [CrossRef]

- Clemens, S.A.C.; Weckx, L.; Clemens, R.; Mendes, A.V.A.; Souza, A.R.; Silveira, M.B. V.; da Guarda, S.N.F.; de Nobrega, M.M.; Pinto, M.I. de M.; Gonzalez, I.G.S.; et al. Heterologous versus Homologous COVID-19 Booster Vaccination in Previous Recipients of Two Doses of CoronaVac COVID-19 Vaccine in Brazil (RHH-001): A Phase 4, Non-Inferiority, Single Blind, Randomised Study. Lancet 2022, 399, 521–529. [CrossRef]

- Fadlyana, E.; Setiabudi, D.; Kartasasmita, C.B.; Putri, N.D.; Rezeki Hadinegoro, S.; Mulholland, K.; Sofiatin, Y.; Suryadinata, H.; Hartantri, Y.; Sukandar, H.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety in Healthy Adults of Full Dose versus Half Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine (ChAdOx1-S or BNT162b2) or Full-Dose CoronaVac Administered as a Booster Dose after Priming with CoronaVac: A Randomised, Observer-Masked, Controlled Trial in I. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 545–555. [CrossRef]

- Sauré, D.; O’Ryan, M.; Torres, J.P.; Zuñiga, M.; Soto-Rifo, R.; Valiente-Echeverría, F.; Gaete-Argel, A.; Neira, I.; Saavedra, V.; Acevedo, M.L.; et al. COVID-19 Lateral Flow IgG Seropositivity and Serum Neutralising Antibody Responses after Primary and Booster Vaccinations in Chile: A Cross-Sectional Study. The Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e149–e158. [CrossRef]

- Mysore, V.; Cullere, X.; Settles, M.L.; Ji, X.; Kattan, M.W.; Desjardins, M.; Durbin-Johnson, B.; Gilboa, T.; Baden, L.R.; Walt, D.R.; et al. Protective Heterologous T Cell Immunity in COVID-19 Induced by the Trivalent MMR and Tdap Vaccine Antigens. Med 2021, 2, 1050-1071.e7. [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, C.; Puranik, A.; Bandi, H.; Venkatakrishnan, A.J.; Agarwal, V.; Kennedy, R.; O’Horo, J.C.; Gores, G.J.; Williams, A.W.; Halamka, J.; et al. Exploratory Analysis of Immunization Records Highlights Decreased SARS-CoV-2 Rates in Individuals with Recent Non-COVID-19 Vaccinations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Haddad-Boubaker, S.; Othman, H.; Touati, R.; Ayouni, K.; Lakhal, M.; Ben Mustapha, I.; Ghedira, K.; Kharrat, M.; Triki, H. In Silico Comparative Study of SARS-CoV-2 Proteins and Antigenic Proteins in BCG, OPV, MMR and Other Vaccines: Evidence of a Possible Putative Protective Effect. BMC Bioinformatics 2021, 22, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Balz, K.; Trassl, L.; Härtel, V.; Nelson, P.P.; Skevaki, C. Virus-Induced T Cell-Mediated Heterologous Immunity and Vaccine Development. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Kenney, L.L.; Mishra, R.; Watkin, L.B.; Aslan, N.; Selin, L.K. Vaccination and Heterologous Immunity: Educating the Immune System. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 109, 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Eggenhuizen, P.J.; Ng, B.H.; Chang, J.; Cheong, R.M.Y.; Yellapragada, A.; Wong, W.Y.; Ting, Y.T.; Monk, J.A.; Gan, P.Y.; Holdsworth, S.R.; et al. Heterologous Immunity Between SARS-CoV-2 and Pathogenic Bacteria. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Ashok, G.; Debroy, R.; Ramaiah, S.; Livingstone, P.; Anbarasu, A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Vaccine Landscape: A Global Perspective. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Jara, A.; Undurraga, E.A.; Zubizarreta, J.R.; González, C.; Acevedo, J.; Pizarro, A.; Vergara, V.; Soto-Marchant, M.; Gilabert, R.; Flores, J.C.; et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac in Children 3–5 Years of Age during the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Outbreak in Chile. Nat. Med. 2022, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Jara, A.; Undurraga, E.A.; Flores, J.C.; Zubizarreta, J.R.; González, C.; Pizarro, A.; Ortuño-Borroto, D.; Acevedo, J.; Leo, K.; Paredes, F.; et al. Effectiveness of an Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Children and Adolescents: A Large-Scale Observational Study. Lancet Reg. Heal. - Am. 2023, 21, 100487. [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F. Systematic Review of COVID-19 in Children Shows Milder Cases and a Better Prognosis than Adults. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2020, 109, 1088–1095. [CrossRef]

- Le Bert, N.; Clapham, H.E.; Tan, A.T.; Chia, W.N.; Tham, C.Y.L.; Lim, J.M.; Kunasegaran, K.; Tan, L.W.L.; Dutertre, C.A.; Shankar, N.; et al. Highly Functional Virus-Specific Cellular Immune Response in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218. [CrossRef]

| Group | n | Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD (U/mL) median (min–max) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A [COVID-19 yes / DTP yes] | 39 | 1,196 (16–15,561) | 0.089 |

| B [COVID-19 yes / DTP no] | 38 | 771.2 (0.3–14,589) | |

| C [COVID-19 no / DTP yes] | 38 | 1,162.5 (0.3–22,269) | |

| D [COVID-19 no / DTP no] | 39 | 527.9 (0.3–9,060) |

| DTP Vaccination Status | n | Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD (U/mL) median (min–max) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 77 | 1,182 (0.3–22,269) | 0.026 |

| No | 77 | 612.5 (0.3–14,589) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).