Submitted:

13 July 2024

Posted:

15 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

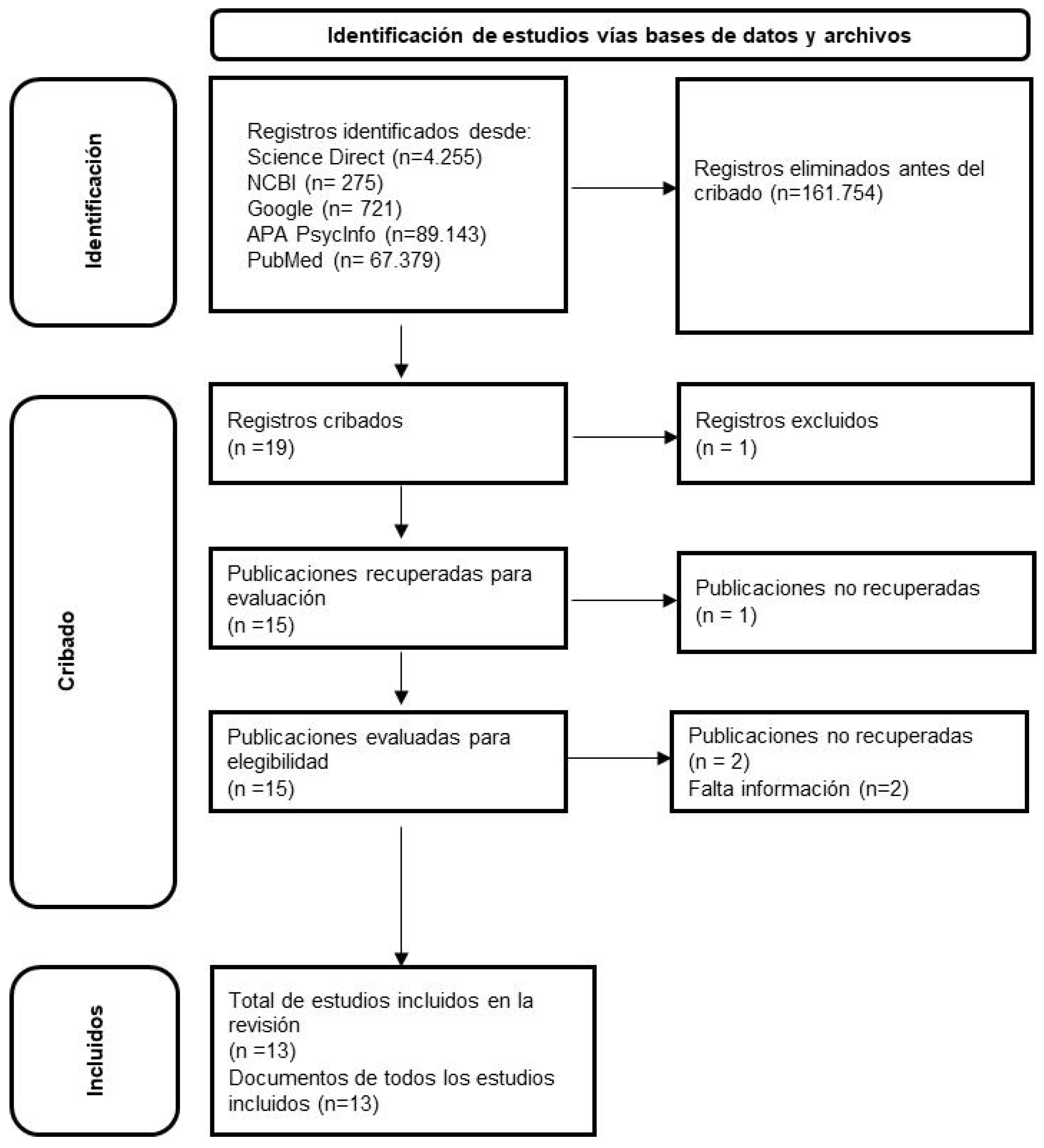

2. Method

Procedure

Selection Criteria

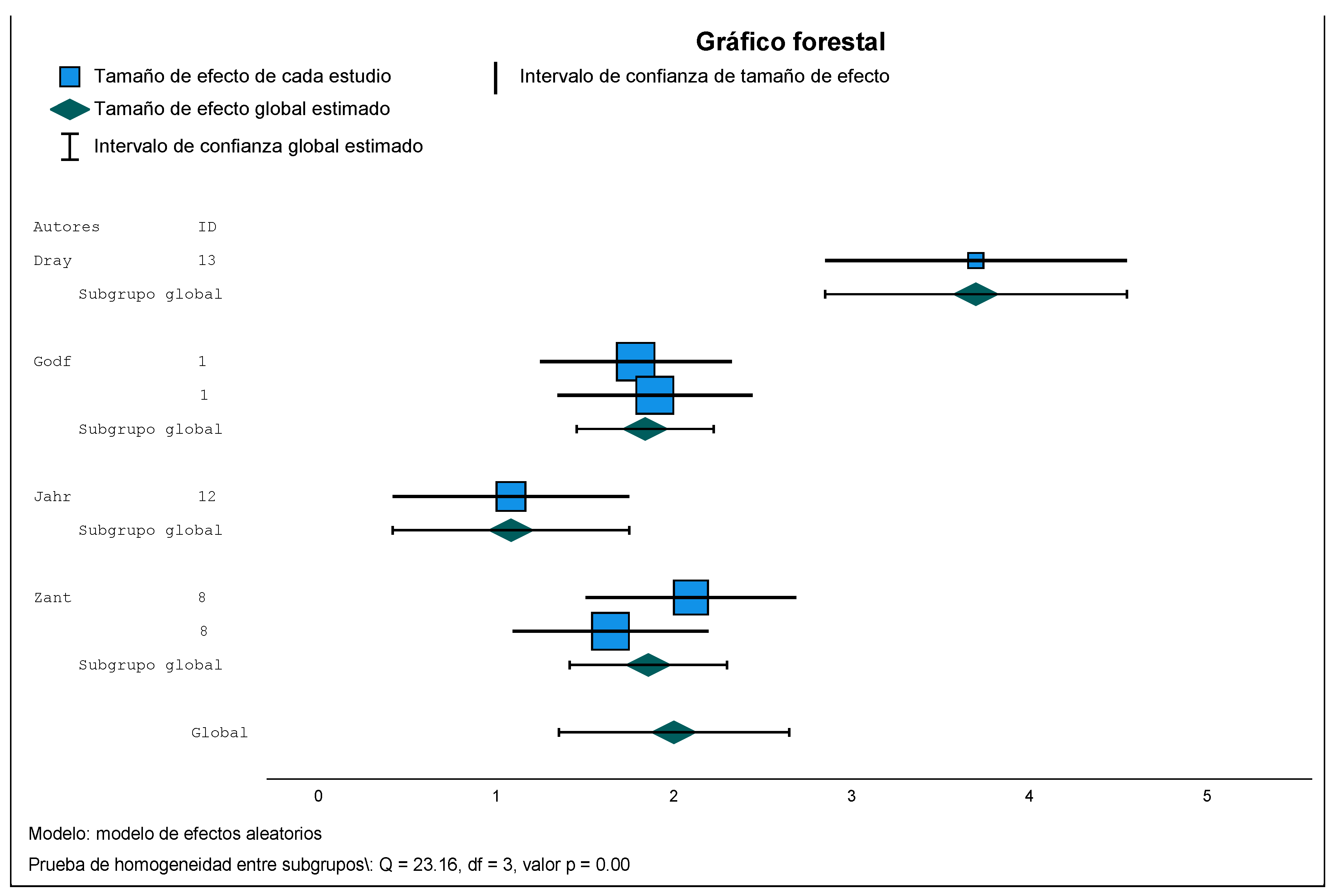

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

References

- Anderson VA, Anderson P, Northam E, Jacobs R, Mikiewicz O. Relationships Between Cognitive and Behavioral Measures of Executive Function in Children With Brain Disease. Child Neuropsychol. diciembre de 2002;8(4):231-40. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo PD, Qu L, Müller U. Hot and cool aspects of executive function: Relations in early development. En: Young children’s cognitive development: Interrelationships among executive functioning, working memory, verbal ability, and theory of mind. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2005. p. 71-93.

- Damasio AR, Maurer RG. A Neurological Model for Childhood Autism. Arch Neurol. 1 de diciembre de 1978;35(12):777-86. [CrossRef]

- Ozonoff S, Pennington BF, Rogers SJ. Executive Function Deficits in High-Functioning Autistic Individuals: Relationship to Theory of Mind. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. noviembre de 1991;32(7):1081-105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell J, editor. Autism as an Executive Disorder (DRAFT) [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 1998 [citado 11 de julio de 2024]. Disponible en: https://academic.oup.com/book/1216.

- Robinson S, Goddard L, Dritschel B, Wisley M, Howlin P. Executive functions in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Brain Cogn. diciembre de 2009;71(3):362-8. [CrossRef]

- Hill EL. Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends Cogn Sci. enero de 2004;8(1):26-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etchepareborda Simonini MC. Funciones ejecutivas y autismo. Rev Neurol. 2005;41(S01):S155.

- Martos-Pérez J, Paula-Pérez I. [An approach to the executive functions in autism spectrum disorder]. Rev Neurol. 1 de marzo de 2011;52 Suppl 1:S147-153.

- Talero-Gutiérrez C, Echeverría Palacio CM, Quiñones PS, Morales Rubio G, Vélez-van-Meerbeke A. Trastorno del espectro autista y función ejecutiva. Acta Neurológica Colomb. 30 de mayo de 2023;31(3):246-52. [CrossRef]

- Best JR, Miller PH. A Developmental Perspective on Executive Function. Child Dev. noviembre de 2010;81(6):1641-60.

- Kenworthy L, Yerys BE, Anthony LG, Wallace GL. Understanding Executive Control in Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Lab and in the Real World. Neuropsychol Rev. diciembre de 2008;18(4):320-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeter ML, Eickhoff SB, Engel A. From correlational approaches to meta-analytical symptom reading in individual patients: Bilateral lesions in the inferior frontal junction specifically cause dysexecutive syndrome. Cortex. julio de 2020;128:73-87. [CrossRef]

- Blijd-Hoogewys EMA, Bezemer ML, Van Geert PLC. Executive Functioning in Children with ASD: An Analysis of the BRIEF. J Autism Dev Disord. diciembre de 2014;44(12):3089-100. [CrossRef]

- Brady DI, Schwean VL, Saklofske DH, McCrimmon AW, Montgomery JM, Thorne KJ. Conceptual and Perceptual Set-shifting executive abilities in young adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Res Autism Spectr Disord. diciembre de 2013;7(12):1631-7. [CrossRef]

- Campbell CA, Russo N, Landry O, Jankowska AM, Stubbert E, Jacques S, et al. Nonverbal, rather than verbal, functioning may predict cognitive flexibility among persons with autism spectrum disorder: A preliminary study. Res Autism Spectr Disord. junio de 2017;38:19-25. [CrossRef]

- Chen SF, Chien YL, Wu CT, Shang CY, Wu YY, Gau SS. Deficits in executive functions among youths with autism spectrum disorders: an age-stratified analysis. Psychol Med. junio de 2016;46(8):1625-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry O, Al-Taie S. A Meta-analysis of the Wisconsin Card Sort Task in Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. abril de 2016;46(4):1220-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eylen L, Boets B, Cosemans N, Peeters H, Steyaert J, Wagemans J, et al. Executive functioning and local-global visual processing: candidate endophenotypes for autism spectrum disorder? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. marzo de 2017;58(3):258-69.

- Blijd-Hoogewys EMA, Bezemer ML, van Geert PLC. Executive Functioning in Children with ASD: An Analysis of the BRIEF. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(12):3089-100. [CrossRef]

- Brady DI, Schwean VL, Saklofske DH, McCrimmon AW, Montgomery JM, Thorne KJ. Conceptual and Perceptual Set-shifting executive abilities in young adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7(12):1631-7. [CrossRef]

- Campbell CA, Russo N, Landry O, Jankowska AM, Stubbert E, Jacques S, et al. Nonverbal, rather than verbal, functioning may predict cognitive flexibility among persons with autism spectrum disorder: A preliminary study. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2017;38:19-25. [CrossRef]

- Chen SFF, Chien YLL, Wu CTT, Shang CYY, Wu YYY, Gau SS. Deficits in executive functions among youths with autism spectrum disorders: An age-stratified analysis. Psychol Med. junio de 2016;46(8):1625-38. [CrossRef]

- Etchepareborda MC. Funciones ejecutivas y autismo. Rev Neurol. 2005;41(1):155-62. [CrossRef]

- Geurts HM, van den Bergh SFWM, Ruzzano L. Prepotent response inhibition and interference control in autism spectrum disorders: Two Meta-Analyses. Vol. 7, Autism Research. 2014. p. 407-20. [CrossRef]

- Hüpen P, Groen Y, Gaastra GF, Tucha L, Tucha O. Performance monitoring in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic literature review of event-related potential studies. Int J Psychophysiol. 2016;102:33-46. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloosterman PH, Kelley EA, Parker JDA, Craig WM. Executive functioning as a predictor of peer victimization in adolescents with and without an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2014;8(3):244-54. [CrossRef]

- Landry O, Al-Taie S. A Meta-analysis of the Wisconsin Card Sort Task in Autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(4):1220-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martos-Pérez J, Paula-Pérez I. Una aproximación a las funciones ejecutivas en el trastorno del espectro autista. Rev Neurol. 2011;52(Supl 1):147-53. [CrossRef]

- Pellicano E, Kenny L, Brede J, Klaric E, Lichwa H, McMillin R. Executive function predicts school readiness in autistic and typical preschool children. Cogn Dev. 2017;43:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Talero C, Echeverria CMa, Sánchez P, Morales G, Vélez A. Trastorno del espectro autista y función ejecutiva. Acta Neurológica Colomb. 2015;31(3):246-52.

- Van Eylen L, Boets B, Cosemans N, Peeters H, Steyaert J, Wagemans J, et al. Executive functioning and local-global visual processing: candidate endophenotypes for autism spectrum disorder? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(3):258-69.

- Vanegas SB, Davidson D. Investigating distinct and related contributions of Weak Central Coherence, Executive Dysfunction, and Systemizing theories to the cognitive profiles of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and typically developing children. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2015;11:77-92. [CrossRef]

- Wu HC, White S, Rees G, Burgess PW. Executive function in high-functioning autism: Decision-making consistency as a characteristic gambling behaviour. Cortex. 2018;1-16. [CrossRef]

- Yi L, Fan Y, Joseph L, Huang D, Wang X, Li J, et al. Event-based prospective memory in children with autism spectrum disorder: The role of executive function. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2014;8(6):654-60. [CrossRef]

- López B, Leekam SR. Teoría de la coherencia central: una revisión de los supuestos teóricos. Infancia Aprendiz. enero de 2007;30(3):439-57.

- Ozonoff S, Strayer DL, McMahon WM, Filloux F. Executive Function Abilities in Autism and Tourette Syndrome: An Information Processing Approach. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. septiembre de 1994;35(6):1015-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith EM, Pennington BF, Wehner EA, Rogers SJ. Executive Functions in Young Children with Autism. Child Dev. julio de 1999;70(4):817-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo M, Di Castelbianco FB, Vanadia E. Assessment of Executive Functions in Preschool-Aged Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Usefulness and Limitation of BRIEF-P in Clinical Practice. J Child Adolesc Behav [Internet]. 2016 [citado 10 de julio de 2024];04(05). Disponible en: http://www.esciencecentral.org/journals/assessment-of-executive-functions-in-preschoolaged-children-withautism-spectrum-disorders-usefulness-and-limitation-of-briefp-incl-2375-4494-1000313.php?aid=81438.

- Isquith PK, Crawford JS, Espy KA, Gioia GA. Assessment of executive function in preschool-aged children. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. agosto de 2005;11(3):209-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennington BF, Ozonoff S. Executive Functions and Developmental Psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. enero de 1996;37(1):51-87. [CrossRef]

- Lai CLE, Lau Z, Lui SSY, Lok E, Tam V, Chan Q, et al. Meta-analysis of neuropsychological measures of executive functioning in children and adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. mayo de 2017;10(5):911-39. [CrossRef]

- Kercood S, Grskovic JA, Banda D, Begeske J. Working memory and autism: A review of literature. Res Autism Spectr Disord. octubre de 2014;8(10):1316-32. [CrossRef]

- Leung RC, Zakzanis KK. Brief Report: Cognitive Flexibility in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Quantitative Review. J Autism Dev Disord. octubre de 2014;44(10):2628-45. [CrossRef]

- Geurts HM, Van Den Bergh SFWM, Ruzzano L. Prepotent Response Inhibition and Interference Control in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Two Meta-Analyses. Autism Res. agosto de 2014;7(4):407-20. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Med. 29 de marzo de 2021;18(3):e1003583.

- Godfrey KJ, Espenhahn S, Stokoe M, McMorris C, Murias K, McCrimmon A, et al. Autism interest intensity in early childhood associates with executive functioning but not reward sensitivity or anxiety symptoms. Autism Int J Res Pract. diciembre de 2021;13623613211064372. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parladé M V., Weinstein A, Garcia D, Rowley AM, Ginn NC, Jent JF. Parent–Child Interaction Therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder and a matched case-control sample. Autism. 2020;24(1):160-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuske HJ, Pellecchia M, Kane C, Seidman M, Maddox BB, Freeman LM, et al. Self-Regulation is Bi-Directionally Associated with Cognitive Development in Children with Autism. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2020;68. [CrossRef]

- Kitzerow J, Hackbusch M, Jensen K, Kieser M, Noterdaeme M, Fröhlich U, et al. Study protocol of the multi-centre, randomised controlled trial of the Frankfurt Early Intervention Programme A-FFIP versus early intervention as usual for toddlers and preschool children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (A-FFIP study). Trials. febrero de 2020;21(1):217. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratto AB, Potvin D, Pallathra AA, Saldana L, Kenworthy L. Parents report fewer executive functioning problems and repetitive behaviors in young dual-language speakers with autism. Child Neuropsychol J Norm Abnorm Dev Child Adolesc. octubre de 2020;26(7):917-33. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens RL, Watson LR, Crais ER, Reznick JS. Infant quantitative risk for autism spectrum disorder predicts executive function in early childhood. Autism Res Off J Int Soc Autism Res. noviembre de 2018;11(11):1532-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacFarlane H, Gorman K, Ingham R, Presmanes Hill A, Papadakis K, Kiss G, et al. Quantitative analysis of disfluency in children with autism spectrum disorder or language impairment. PloS One. 2017;12(3):e0173936. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zantinge G, van Rijn S, Stockmann L, Swaab H. Physiological Arousal and Emotion Regulation Strategies in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. septiembre de 2017;47(9):2648-57. [CrossRef]

- Gorman K, Olson L, Hill AP, Lunsford R, Heeman PA, van Santen JPH. Uh and um in children with autism spectrum disorders or language impairment. Autism Res Off J Int Soc Autism Res. agosto de 2016;9(8):854-65.

- Di Renzo M, di Castelbianco FB, Vanadia E. Assessment of Executive Functions in Preschool-Aged Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Usefulness and Limitation of BRIEF-P in Clinical Practice. J Child Adolesc Behav. 2016;04(05). [CrossRef]

- Smithson PE, Kenworthy L, Wills MC, Jarrett M, Atmore K, Yerys BE. Real world executive control impairments in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. agosto de 2013;43(8):1967-75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahromi LB, Bryce CI, Swanson J. The importance of self-regulation for the school and peer engagement of children with high-functioning autism. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7(2):235-46. [CrossRef]

- Drayer JD. Profiles of executive functioning in preschoolers with autism. Diss Abstr Int Sect B Sci Eng. 2009;69(12-B):7834.

- Jahromi LB, Bryce CI, Swanson J. The importance of self-regulation for the school and peer engagement of children with high-functioning autism. Res Autism Spectr Disord. febrero de 2013;7(2):235-46. [CrossRef]

- McClain MB, Golson ME, Murphy LE. Executive functioning skills in early childhood children with autism, intellectual disability, and co-occurring autism and intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil. marzo de 2022;122:104169. [CrossRef]

- Godfrey KJ, Espenhahn S, Stokoe M, McMorris C, Murias K, McCrimmon A, et al. Autism interest intensity in early childhood associates with executive functioning but not reward sensitivity or anxiety symptoms. Autism. octubre de 2022;26(7):1723-36. [CrossRef]

- Ratto AB, Potvin D, Pallathra AA, Saldana L, Kenworthy L. Parents report fewer executive functioning problems and repetitive behaviors in young dual-language speakers with autism. Child Neuropsychol. 2 de octubre de 2020;26(7):917-33. [CrossRef]

- Otterman DL, Koopman-Verhoeff ME, White TJ, Tiemeier H, Bolhuis K, Jansen PW. Executive functioning and neurodevelopmental disorders in early childhood: a prospective population-based study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. diciembre de 2019;13(1):38. [CrossRef]

- Stephens RL, Watson LR, Crais ER, Reznick JS. Infant quantitative risk for autism spectrum disorder predicts executive function in early childhood. Autism Res. noviembre de 2018;11(11):1532-41. [CrossRef]

- Gorman K, Olson L, Hill AP, Lunsford R, Heeman PA, Van Santen JPH. Uh and um in children with autism spectrum disorders or language impairment. Autism Res. agosto de 2016;9(8):854-65.

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cognit Psychol. agosto de 2000;41(1):49-100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Neurodevelopmental Disorder | Executive Deficits |

|---|---|---|

| [20] | ASD | Flexibility |

| [14,21] | ASD (syndrome de Asperger) | Conceptual flexibility |

| [22] | ASD (no verbal) | Flexibility |

| [23] | ASD | Working memory and planning in youth (13-18 years) Flexibility in children (8-12 years old) |

| [24] | ASD | Inhibition, flexibility and planning |

| [25] | ASD | Inhibition, working memory, cognitive flexibility, and planning |

| [26] | ASD | Self-monitoring of learning |

| [27] | ASD | Emotional control |

| [28] | ASD | Rigidity (not flexibility) |

| [29] | ASD | Planning, mental and cognitive flexibility and response inhibition |

| [30] | ASD | Inhibition and working memory |

| [31] | ASD | Executive Function (unitary construct) |

| [32] | ASD | Flexibility, fluency and inhibition of automatic responses |

| [33] | ASD | Executive Function (unitary construct) |

| [34] | ASD | Repetition, rigidity |

| [35] | ASD | Prospective report |

| Author/ Year/ Country |

Design | Sample/n | Sample/Median age | Diagnostic instrument_ASD | Assessment instrument for EF | Assessment instrument for other competencies | Executive profile | Included in the meta-analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [47] / Canada |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Causal 2 groups: -ASD -Comparison |

-ASD= 33 -Comparison = 42 |

3-6 years | >Social Responsiveness Scale–Second Edition (SRS-2) (versión padres) | BRIEF-P | >The Interests Scale (IS) >The Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Approach System–Parent Version (BISBAS) >Behavior Assessment System for Children–Third Edition (BASC-3) |

>The group with ASD had greater difficulties on the Flexibility clinical scale and on the Inhibitory control index | YES |

| [48]/ Canada |

Empirical Quasi-experimental Measures: pre-test and post-test 2 groups: -ASD -Control |

-ASD=16 -Comparison= 16 |

3-7 years | > The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd-edition (ADOS-2) | BRIEF-P | >Differential Abilities Scale, Second Edition (DAS-II) >Picture Vocabulary Test, Fourth Edition (PPVT-4) >Expressive Vocabulary Test, Second Edition (EVT-2) >Peabody Parenting Stress Index, Fourth Edition: Short Form (PSI-4: SF) > ECBI >Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition, Parent Rating Scale (BASC-2 PRS) >Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2) |

>There are no statistically significant differences in the BRIEF-P Global Executive Functioning Scale between pre- and post-treatment | NO |

| [49])/ EE.UU |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Causal 2 groups: -Minimally verbal -Typically verbal |

ASD: -Minimally verbal children= 38 -Typically verbal children=46 |

5-8 years | > Differential Ability Scales-II (DAS-II) | BRIEF-P | >Behavioral Interference Coding Scheme (BICS) | >Children with ASD are at high risk of self-regulation difficulties >Children with ASD who were minimally verbal, compared with typically verbal, had more self-regulation difficulties >Reduction in self-regulation difficulties over one academic year predicted greater gains in cognitive skills and vice versa |

NO |

| [50]/ Germany |

Quasi-experimental 1 group with 6 measurements |

ASD=134 | 24-66 months (2-5.5 years) |

> Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised (ADI-R) > The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd-edition (ADOS-2) |

BRIEF-P | > Brief Observation of Social Communication Change (BOSCC) > Social Responsiveness Scale – short versión (SRS-16) > Repetitive Behavior Scale – Revised (RBS-R) > Child Behavior Checklist 1 ½-5 (CBCL 1 ½-5) > Parent sense of competence scale (PSOC) > Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale – short form (DASS-21) > Family quality of Life Survey (FQOLS) > Early Social Communication Scale (ESCS) > Dyadic Communication Measure for Autism (DCMA) > Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development 3rd Edition (Bayley-III) > Parent Adherence to treatment and Competence Scale (PATCS) |

>In preschool children with ASD, EF disturbances were observed in the real world that were not related to ASD symptoms >Given the relevance of EF problems in adulthood, change in EF through early intervention is an important outcome |

NO |

| [51]/ EE.UU |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Cause 2 groups: - Bilingual -Monolingual |

ASD: -Bilingual= 24 -Monolingual= 31 |

Dual-Language= 4.73 (0.57) Monolingual= 4.76 (0.67) |

> The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd-edition (ADOS-2) | BRIEF-P | >The Social Responsiveness Scale-2 (SRS-2) >The Vineland-II |

>The bilingual advantage of EF observed in children with normotypical development may also be extended to young children with ASD | NO |

| [52]/ EE.UU |

Non-experimental Descriptive |

ASD= 585 | 42 months (3.5 years) | >The First Year Inventory 2.0 (FYI 2.0) | BRIEF-P | >Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2.0) | > Certain childhood behaviours related to ASD are linked to EF difficulties in early childhood | NO |

| [53]/ EE.UU |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Cause 3 groups: - ASD - Language impairment - Control |

-ASD=47 -Control=32 -Language impairment =18 |

4-8 years | >Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) | BRIEF-P | >Verbal IQ (VIQ), performance IQ (PIQ) and full-scale IQ (FSIQ) the Wechsler scales tests > CELF Preschool-2 > Communication Checklist (CCC-2) |

> Executive functioning difficulties are more common in individuals with ASD than in children with language disorders | NO |

| [54]/ Netherlands |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Cause 2 groups: - ASD - Control |

-ASD=27 -Control= 44 |

41-81 months (3,4-6.75 years) |

>Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI) |

BRIEF-P | >Dutch Wechsler Nonverbal Scale of Abil-ity (WNV-NL) >Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI-III-NL) >Nonverbal Intelligence Test (SON-R 2.5–7) >Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) > Wechsler Nonverbal Scale of Ability (WNV) >Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) >Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III-NL (PPVT-III-NL) >Locked Box Task |

>Children with ASD had significantly more problems with inhibitory control and mental flexibility compared to children in the control group | YES |

| [55]/ EE.UU |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Cause 3 groups: - ASD - Control - Especific Language Impairment |

-ASD=50 -TD=47 -Especific Language Impairment=17 |

4-8 years | >Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) | BRIEF-P | >Children’s Communication Checklist (CCC-2) >Social Communication Questionnaire |

>There were no reliable associations between um:uh ratio and chronological age, intelligence, or Executive Function | NO |

| [56]/ Italia |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Cause 4 groups: - ASD -Autistc children -Autism Spectrum Children -Children at risk of autism |

-ASD=46 -AUT=26 -SpD= 7 -Risk= 13 |

24-76 months (2-6.3 years) |

> The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, 2nd-edition (ADOS-2) | BRIEF-P | >The Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (Leiter-R) | >BRIEF-P administered by professionals is a useful tool to define the profile of individual development in preschool, but it is not indicative of the severity of autistic symptoms. Therefore, in ASD it could be used to define the “specifier” of Executive Functioning, in line with the DSM-5 suggestion. Based on these considerations, the evaluation of EF cannot be left solely in the hands of a questionnaire such as the BRIEF-P, administered by professionals, but must be supported by a clinical diagnosis carried out by professionals with training and experience in autism within a multidisciplinary ASDm. | NO |

| [57]/ EE.UU |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Cause 2 groups: - ASD -Control |

-ASD= 39 -Control=39 |

2.83–5.83 years | >Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) | BRIEF-P | >Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised (WPPSI-R) >Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Third Edition (WPPSI-III) >WPPSI-III and WPPSI-R |

>Preschoolers with ASD showed generalised deficits in Executive Control when informants were parents. They have greater difficulties in: inhibition, flexibility, emotional control, working memory, and planning/organisation | NO |

| [58]/ EE.UU |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Cause 2 groups: - ASD -Control |

-ASD_high performance=20 -Control=20 |

54.57 months (4.55 years) |

>Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) |

BRIEF-P | >Child Behavior Questionnaire–Short Form (CBQ-SF) | >Emotion regulation was positively related to performance in the Day/Night inhibition task, and was negatively related to deficits on the Inhibitory Control Index in the BRIEF-P | YES |

| [59]/ EE.UU |

Non-experimental Descriptive Comparative/Cause 2 groups: - ASD - Persasive Developmental Disorder |

-ASD=29 -Control=30 |

4-6 years | Schooled in a Special Education center being consulted on the clinical diagnosis. | BRIEF-P | >The Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised (Leiter-R) | >ASDchers in the group of children with ASD reported a higher level of difficulty in Executive Functioning skills in all domains, compared to the group of children without autism. It is noteworthy that the mean Global Executive Functioning Index score was five times higher in the ASD group compared to the non-ASD group. | YES |

| Author/Year/Country | Probabilidad de sesgos | Preocupación sobre la aplicabilidad de los resultados | |||||

| Selección de los individuos | Prueba índice | Prueba de referencia | Flujo y tiempos | Selección de los pacientes | Prueba índice | Prueba de referencia | |

| [47] /Canada | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO | INCIERTO | BAJO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [48]/Canada | BAJO | BAJO | INCIERTO | INCIERTO | BAJO | INCIERTO | INCIERTO |

| [49])/EE.UU | ALTO | INCIERTO | INCIERTO | INCIERTO | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [50]/Germany | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO | BAJO | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [51]/EE.UU | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [52]/EE.UU | BAJO | BAJO | BAJO | INCIERTO | BAJO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [53]/EE.UU | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO | INCIERTO | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [54]/Netherlands | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO | INCIERTO | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [55]/EE.UU | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO | INCIERTO | BAJO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [56]/Italia | ALTO | ALTO | BAJO | INCIERTO | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [57]/EE.UU | ALTO | ALTO | BAJO | INCIERTO | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO |

| [58]/EE.UU | ALTO | ALTO | INCIERTO | INCIERTO | BAJO | INCIERTO | ALTO |

| [59]/EE.UU | ALTO | ALTO | BAJO | INCIERTO | ALTO | BAJO | BAJO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).