1. Introduction

GLA gene encodes for α-galactozidase enzyme and its over 850 pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are all associated with the only clinical phenotype - Anderson-Fabry disease (AFD). This disease results from decreased enzyme activity and intralyzosomal storage of its nonhydrolyzed substrate – globotriaozilceramide [

1,

1]. The most suffering cells and tissues are heart, kidney and nervous system, as well as eyes and ears due to endothelial damage and intracellular storage of undegraded substrates [

2]. The classical form of the disease progress permanently leading to substantial decrease of quality of life and life expectancy [

3]. Cadiovascular complications contribute substantially for AFD-patient’s mortality and since one half of the patients without left ventricular hypertrophy develop it within 15 years [

4]. Apart from classical form with typical presentation and systemic organ damage there have been described non-classical and non-penetrant forms with late manifestation and isolated organ involvement – mainly cardiovascular system or kidney. These cases constitute a substantial diagnostic challenge often leaving the patient without correct clinical and genetically proved diagnoses, enzyme replacement therapy or proper estimation of risk factors. Thus, despite the fact that hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a well-known cardiovascular presentation of Fabry disease in a form of subaortic, midventricular or apical hypertrophic remodeling, there are only several reports on obstructive form of AFD-HCM demanding surgical septal myectomy (SSM) [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In most of the cases the patients reported were admitted to surgical treatment with already established diagnosis of AFD and only in few cases the patients were treated as having classical HCM and the precise diagnosis became obvious only after cardiac surgery. Here we report three new cases of obstructive HCM due to unclassical presentation of AFD and isolated cardiac involvement. In all three cases the diagnosis of AFD was made postoperative by routine genetic and morphological testing. In addition, we summarize all previously published cases of SSM in patients with AFD giving the summary on a safety and benign prognosis of such operations in patients with AFD. Our series in addition to previously reported underlines the safety and effectiveness of SSM in obstructive form of AFD.

2. Case Reports

Three patients were enrolled in Almazov National Medical Research Centre during 2016-2022 to perform SSM due to obstructive form of HCM without previously known diagnosis of ADF disease. The main clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in

Table 1. In all patients, standard clinical examination including echocardiography and Holter ECG monitoring were performed prior to cardiac surgery. MRI images were obtained using ultra-high field tomography Magnetom Trio A Tim 3,0 Тл (Siemens) with 8 mm slices using Gd-DO3A 0,2 ml/kg contrasting. Of note, two out of three patients underwent non-ST MI prior to operation and one of them had classical angina without any intracoronary obstruction according to angiography. In one patient a pacemaker was implanted due to II-degree AV-block (type 2). Nobody of the patients revealed ventricular tachycardia, while all three presented with premature ventricular contractions grade III-IV Ryan. All patients revealed various degree of myocardial fibrosis according to MRI either in bother ventricles (Patient 1), in IVS and LV (Patient 2) or solely in left ventricle (Patient 3). Only Patient 1 had increased right ventricular thickness. All surgical procedures were performed with cardiac arrest under retrograde Calafiore blood cardioplegia according to B. Messmer modification [

13]. In one case (Patient 1) vena cava superior was dissected in order to verticalize interventricular septum due to poor visualisation. In Patient 3 mitral

second-order chordae resection of anterior mitral valve leaflet was performed [

14]. All three patients had no postsurgical complications and were discharged at day 14-16 with remarkable clinical and subjective improvement (CHF class I-II and no signs of angina). Morphological examination confirmed extensive fibrosis and disarray.

All patients were alive 12 and 18 month postoperatively and remained on CHF II (Patients 1 and 2) and class I (Patient 3). Of note, in all three patients CHF symptoms along with elevated NT-proBNP level persisted one year after surgery despite a marked reduction of LVOT gradient. In addition, none of the patient demonstrated clinically marked PVC and or had indications for ICD implantation in spite of severe LVOD gradient before surgery.

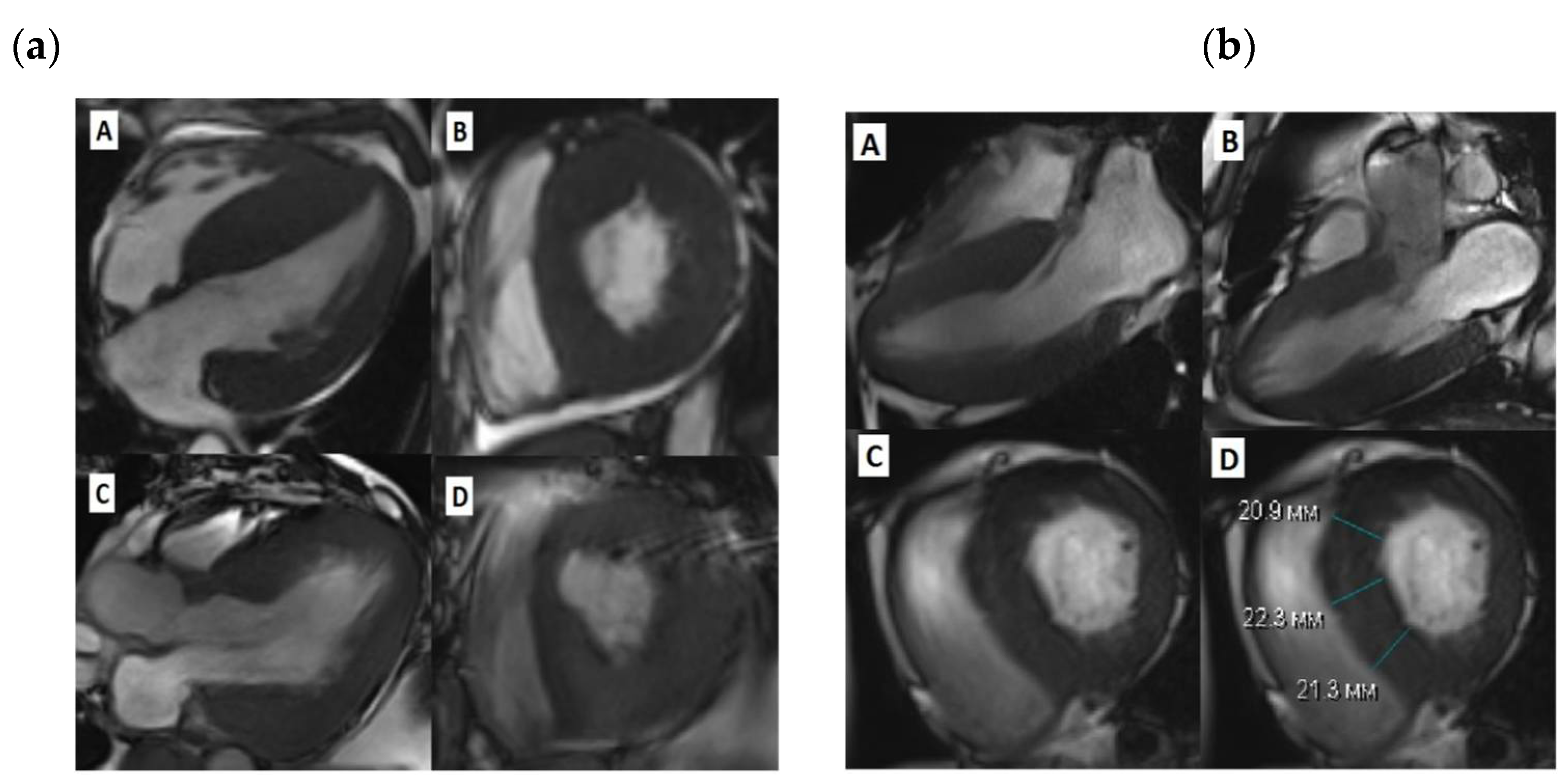

Figure 1.

Cardiac MRI before and after SSM. (a)-Patient 1, A-diastolic view before SSM, long LV axis, B- diastolic view before SSM, short LV axis, C -diastolic view after SSM, long LV axis, D-diastolic view after SSM, short LV axis; (b)-Patient 3, A, B-diastolic view before SSM, long LV axis, C,D -diastolic view before SSM, short LV axis;.

Figure 1.

Cardiac MRI before and after SSM. (a)-Patient 1, A-diastolic view before SSM, long LV axis, B- diastolic view before SSM, short LV axis, C -diastolic view after SSM, long LV axis, D-diastolic view after SSM, short LV axis; (b)-Patient 3, A, B-diastolic view before SSM, long LV axis, C,D -diastolic view before SSM, short LV axis;.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic data of HOCM patients before myectomy.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic data of HOCM patients before myectomy.

| Clinical parameter |

Case 1 |

Case 2 |

Case 3 |

| IVS mm |

32 |

25 |

17 |

| LVPW (d) mm |

26 |

16 |

12 |

| LVOT max gradient, mmHg. |

112 |

130 |

110 |

| LA mm |

52 |

|

|

| LV EF % |

74 |

78 |

73 |

| RVW (d) mm |

9 |

5 |

4 |

| ТАРSE |

22 |

21 |

20 |

| SAM +\- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| MR |

0 |

I – II |

II – III |

Table 3.

Intraoperative characteristic of patients with HOCM during SSM.

Table 3.

Intraoperative characteristic of patients with HOCM during SSM.

| Intraoperative characteristics |

Patient 1 |

Patient 2 |

Patient 3 |

| Type of surgery |

Extended myectomy |

Extended myectomy |

Extended myectomy+MV plastic |

| Time of circulatory arrest (min) |

70 |

62 |

60 |

| Time of aorta clip (min) |

43 |

55 |

49 |

| Excised myocardial mass (gr) |

6,37 |

8,1 |

3,41 |

| IVS thickness at subaortic level (mm) |

16 |

16 |

10 |

| LV maximum thickness (mm) |

31 |

16 |

15 |

| Maximum LVOT gradient |

30 |

12,9 |

11,9 |

| LV EF % at day 7 postoperatively |

71 |

69 |

63 |

| MR* |

0 |

I |

0 |

3. Discussion

In spite of a well-known fact that AFD often manifests with cardiac phenotype in a form of HCM, the diagnostic work up in case with atypical AFD with only cardiovascular symptoms remains a challenge. Importantly, since the use of HCM risk calculator is not validated for patients with storage diseases, no straightforward clinical guidelines for ICD implantation can be used in patients with identified

GLA mutations. The same is valid for other treatment strategies of HCM in case of metabolic and storage disorders. This group of patients drops off the current guidelines and treatment algorithms since these patients fully manifests neither classical signs of AFD phenotype no HCM clinical cause. For this reason, a newly proposed staging for AFD-associated HCM was recently offered to better define the treatment strategy, surgical risks and patient’s prognosis [

15]. Currently, AFD contributes for only small proportion of HCM, approximately 0.4-1% [

11,

16]. However, with implementation of routine genetic testing in HCM diagnostics the number of reported patients with non-classical AFD among HCM patients is constantly increasing including a group of surgically treated patients. Thus, among patients with HOCM AFD is reported to contribute to 0,5-2% [

10]. Several interventional and surgical options can be offered to patients with HOCM including myectomy and septal alcohol ablation [

17]. Myectomy also aims on reducing LVOT gradient, relieving the exercise intolerance and improving HF symptoms in patients with LVOT obstruction. Of note, in growing number of cases the defined diagnosis of AFD is established only during surgical operation due to operators attention to the myocardial tissue structure, meaning that a number of patients with HOCM do not have any red flags of AFD prior to surgery [

9]. However, storage disorders are often considered as an untarget group for myectomy since no systematic data, review or metanalysis are performed on the effectiveness of surgical treatment and the cause of postoperative period in this group of patients.

Several case reports have been described on patients with AFD performed surgical myectomy. Together with 3 patients presented in this study overall 22 patients who underwent open surgery treatment due to HOCM and AFD are reported by now (

Table 4). In almost half of the cases the diagnosis of AFD was established prior to surgery and 9 out of 22 patients obtained enzyme replacement therapy.

Importantly, despite of the well documented effect of ERT for patients with AFD in terms of the organ damage and disease progression [

18], its protective effect on progression of cardiomyopathy and relieving HF symptoms is not obvious [

19,

20]. One of the explanations can be related to the possible immune and cell-stress-mediated mechanisms of cardiomyocyte injury and hypertrophy in AFD-cardiomyopathy, which are, once being induced, can undulate long time in spite of the absence of initial metabolic alterations and effective ERT [

19,

21]. This notion can be supported by the fact that 9 out of 22 patients underwent myectomy had ERT and, however, reached the indication for surgical treatment due to progression of hypertrophy and obstruction. Data exists regarding the most beneficial effect of ERT or chaperon therapy with megalostat on cardiac function in patients with very early stage of cardiac involvement and the decreased effect of specific therapy on cardiac function in patient with advanced cardiomyopathy and hypertrophy [

19,

21,

22]. Importantly, the molecular mechanism of cardaiac-only AFD can be slightly different from the cases with full disease penetrance and classical presentations. This probably is associated with a defined genetic alteration and the functional effect of the variant of enzyme activity and function. Thus, Ala143Thr variant described in this study has been widely debated as a causative for full-penetrant phenotype of AFD and is demonstrated to be associated with only latte onset cardiomyopathy with incomplete penetrance [

23]. Similar is valid for the genetic variant which lead to formation of cryptic splice site and inclusion of addition exones [

24]. These low penetrant

GAL variants and variants in non-coding regions which are not always covered by target gene panels have to be considered in patients with HOCM as a possible cause of AFD-cardiac only phenotype.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we described three new cases of successful SSM in patients with HOCM due to AFD. In all three patients the genetic diagnosis was established only after surgical procedure since patients did not have other classical symptoms of AFD. Together with previously published cases this report illustrates the potential safely and beneficial effect of SSM in patients with AFD-HOCM, as well as underlines the need for more thorough screening for clinical signs of AFD-associated cardiomyopathy and GLA variants among patients with HOCM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.G., A.K., M.G., O.M; methodology: S.A., V.Z., P.K., G.I., A.Koz; validation: P.S., V.Z,; formal analysis: A.G. S.A., O.M.; investigation: A.Koz., P.S., P.K., G.I.; data curation: O.M., A.K, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation: A.G., P.S., A.R; writing—review and editing A.K., M.G., P.S., supervision: A.K., M.G..; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Agreement No. 075-15-2022-301)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Almazov National Research Center (protocol code 0101-22-01C).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study can be requested from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Weissman D., Dudek J., et al. Fabry Disease: Cardiac Implications and Molecular Mechanisms. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2024, 21, 81-100,Kurdi H., Lavalle L., et al. Inflammation in Fabry disease: stages, molecular pathways, and therapeutic implications. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11, 1420067. [CrossRef]

- Germain D.P. Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010, 5, 30.

- Pieroni M., Moon J.C., et al. Cardiac Involvement in Fabry Disease: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021, 77, 922-936. [CrossRef]

- Monda E., Bakalakos A., et al. Incidence and risk factors for development of left ventricular hypertrophy in Fabry disease. Heart 2024, 110, 846-853,Monda E., Falco L., et al. Cardiovascular Involvement in Fabry's Disease: New Advances in Diagnostic Strategies, Outcome Prediction and Management. Card Fail Rev 2023, 9, e12,Meucci M.C., Lillo R., et al. Prognostic Implications of the Extent of Cardiac Damage in Patients With Fabry Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 82, 1524-1534.

- Meghji Z., Nguyen A., et al. Surgical septal myectomy for relief of dynamic obstruction in Anderson-Fabry Disease. Int J Cardiol 2019, 292, 91-94. [CrossRef]

- Kunkala M.R., Aubry M.C., et al. Outcome of septal myectomy in patients with Fabry's disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2013, 95, 335-337. [CrossRef]

- Raju B., Roberts C.S., et al. Ventricular Septal Myectomy for the Treatment of Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction Due to Fabry Disease. Am J Cardiol 2020, 132, 160-164. [CrossRef]

- Blount J.R., Wu J.K., et al. Fabry's disease with LVOT obstruction: diagnosis and management. J Card Surg 2013, 28, 695-698. [CrossRef]

- Cecchi F., Iascone M., et al. Intraoperative Diagnosis of Anderson-Fabry Disease in Patients With Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Undergoing Surgical Myectomy. JAMA Cardiol 2017, 2, 1147-1151. [CrossRef]

- Frustaci A., Borghetti V., et al. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy caused by Fabry disease: implications for surgical myectomy. ESC Heart Fail 2023, 10, 3710-3713. [CrossRef]

- Xiao Y., Sun Y., et al. Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Fabry Disease in Chinese Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Med Sci 2021, 362, 260-267. [CrossRef]

- Calcagnino M., O'Mahony C., et al. Exercise-induced left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in symptomatic patients with Anderson-Fabry disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 58, 88-89. [CrossRef]

- Messmer B.J. Extended myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg 1994, 58, 575-577.

- Ferrazzi P., Spirito P., et al. Transaortic Chordal Cutting: Mitral Valve Repair for Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy With Mild Septal Hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015, 66, 1687-1696. [CrossRef]

- Del Franco A., Iannaccone G., et al. Clinical staging of Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy: An operative proposal. Heart Fail Rev 2024, 29, 431-444. [CrossRef]

- Oktay V., Tufekcioglu O., et al. The Definition of Sarcomeric and Non-Sarcomeric Gene Mutations in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Patients: A Multicenter Diagnostic Study Across Turkiye. Anatol J Cardiol 2023, 27, 628-638,Silva S.M.E., Chaves A.V.F., et al. Multinational experience with next-generation sequencing: opportunity to identify transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and Fabry disease. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2024, 14, 294-303,Savostyanov K., Pushkov A., et al. The prevalence of Fabry disease among 1009 unrelated patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a Russian nationwide screening program using NGS technology. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2022, 17, 199.

- Zemanek D., Marek J., et al. Usefulness of Alcohol Septal Ablation in the Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction in Fabry Disease Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2021, 150, 110-113. [CrossRef]

- Eng C.M., Guffon N., et al. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human alpha-galactosidase A replacement therapy in Fabry's disease. N Engl J Med 2001, 345, 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Maurizi N., Nowak A., et al. Fabry disease: development and progression of left ventricular hypertrophy despite long-term enzyme replacement therapy. Heart 2024. [CrossRef]

- Frustaci A., Verardo R., et al. Long-Term Clinical-Pathologic Results of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Prehypertrophic Fabry Disease Cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc 2024, 13, e032734. [CrossRef]

- Graziani F., Lillo R., et al. Evidence of evolution towards left midventricular obstruction in severe Anderson-Fabry cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Fail 2021, 8, 725-728. [CrossRef]

- Camporeale A., Bandera F., et al. Effect of Migalastat on cArdiac InvOlvement in FabRry DiseAse: MAIORA study. J Med Genet 2023, 60, 850-858,Monda E., Bakalakos A., et al. Targeted Therapies in Pediatric and Adult Patients With Hypertrophic Heart Disease: From Molecular Pathophysiology to Personalized Medicine. Circ Heart Fail 2023, 16, e010687.

- Terryn W., Vanholder R., et al. Questioning the Pathogenic Role of the GLA p.Ala143Thr "Mutation" in Fabry Disease: Implications for Screening Studies and ERT. JIMD Rep 2013, 8, 101-108,Lenders M., Weidemann F., et al. Alpha-Galactosidase A p.A143T, a non-Fabry disease-causing variant. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2016, 11, 54,Valtola K., Nino-Quintero J., et al. Cardiomyopathy associated with the Ala143Thr variant of the alpha-galactosidase A gene. Heart 2020, 106, 609-615.

- Higuchi T., Kobayashi M., et al. Identification of Cryptic Novel alpha-Galactosidase A Gene Mutations: Abnormal mRNA Splicing and Large Deletions. JIMD Rep 2016, 30, 63-72,Ferri L., Covello G., et al. Double-target Antisense U1snRNAs Correct Mis-splicing Due to c.639+861C>T and c.639+919G>A GLA Deep Intronic Mutations. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e380,Okada E., Horinouchi T., et al. All reported non-canonical splice site variants in GLA cause aberrant splicing. Clin Exp Nephrol 2023, 27, 737-746.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).