Submitted:

12 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Study Site and Data Sources

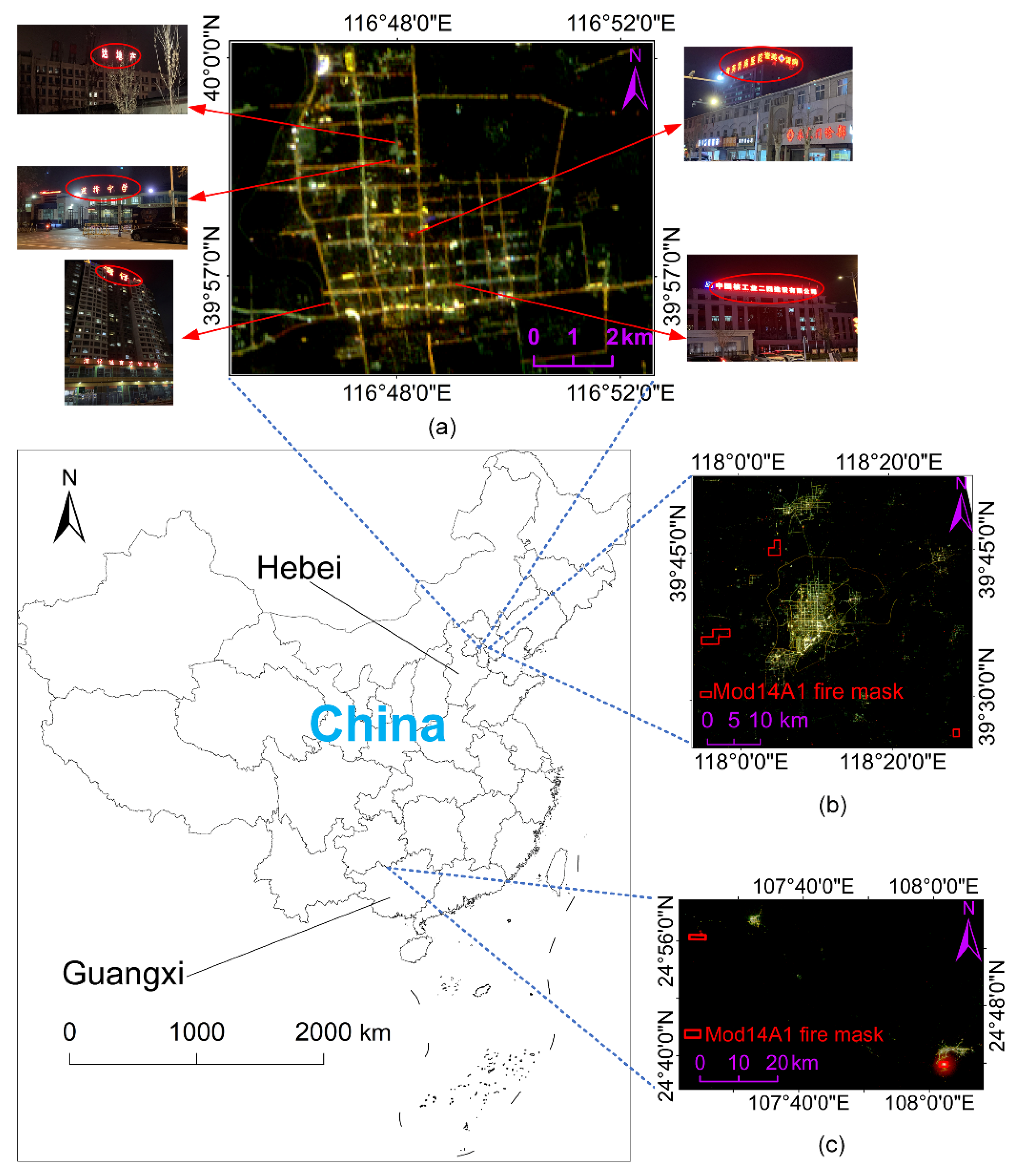

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Data Sources

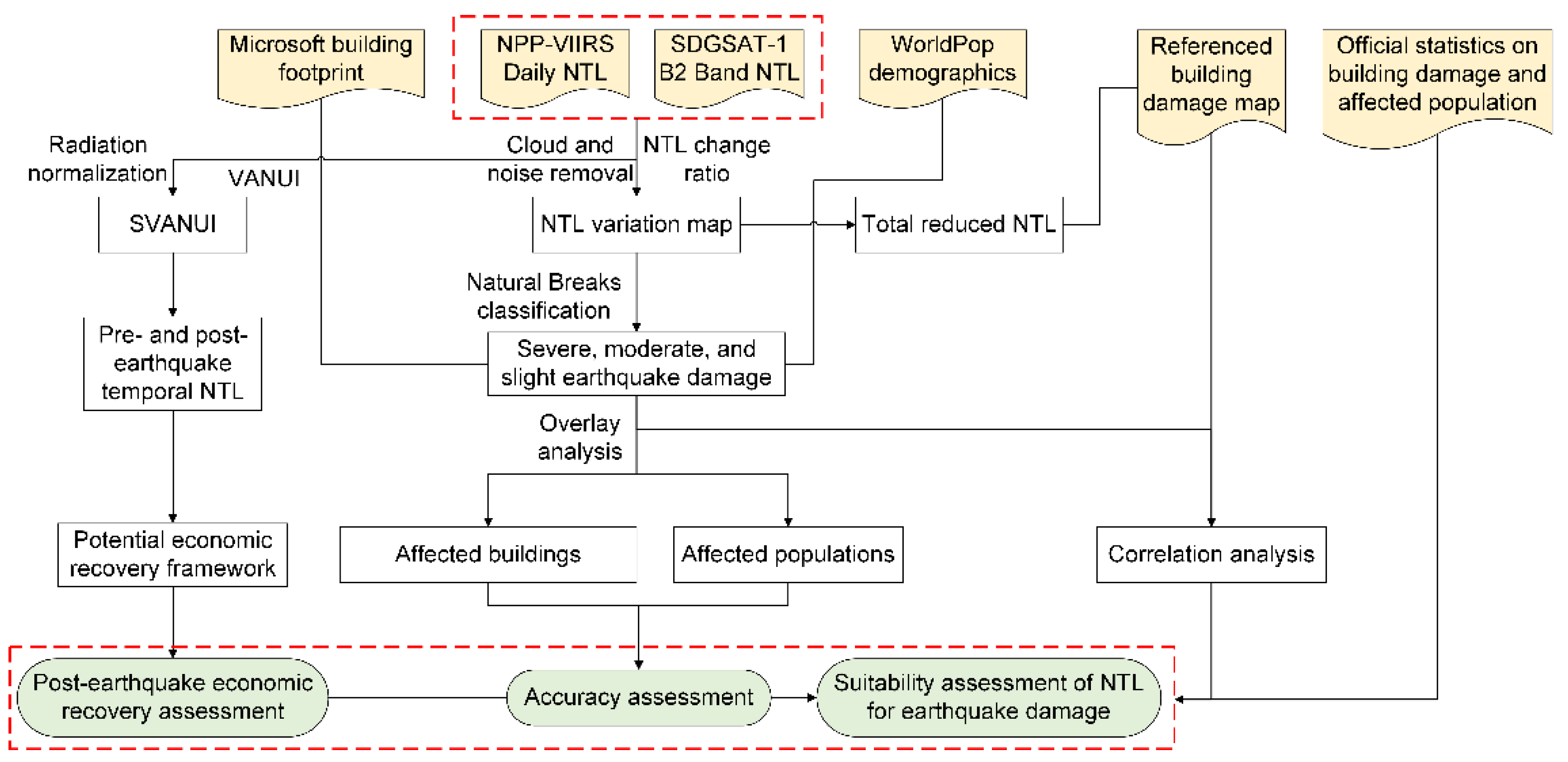

3. Methodology

3.1. Assessment Methods of Earthquake Damage for Two NTL Sensors

3.1.1. Assessment Method of Earthquake Damage for NPP-VIIRS NTL

3.1.2. Assessment Method of Earthquake Damage for SDGSAT-1 NTL

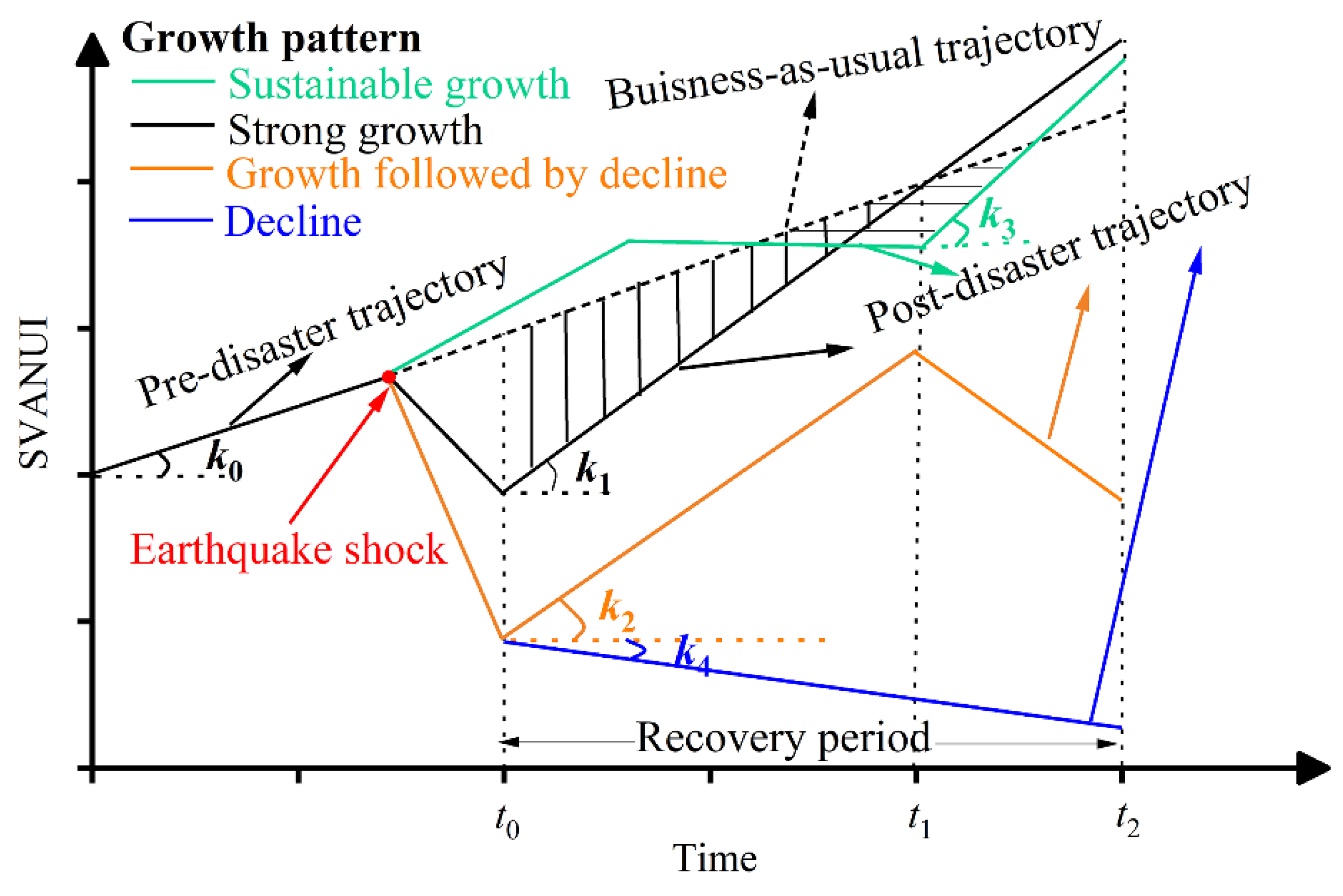

3.2. Assessment Method of Eonomic Recovery from Affected Area

4. Results

4.1. Accuracy Assessment of Earthquake Damage

4.2. Earthquake Damage Map from NTLs

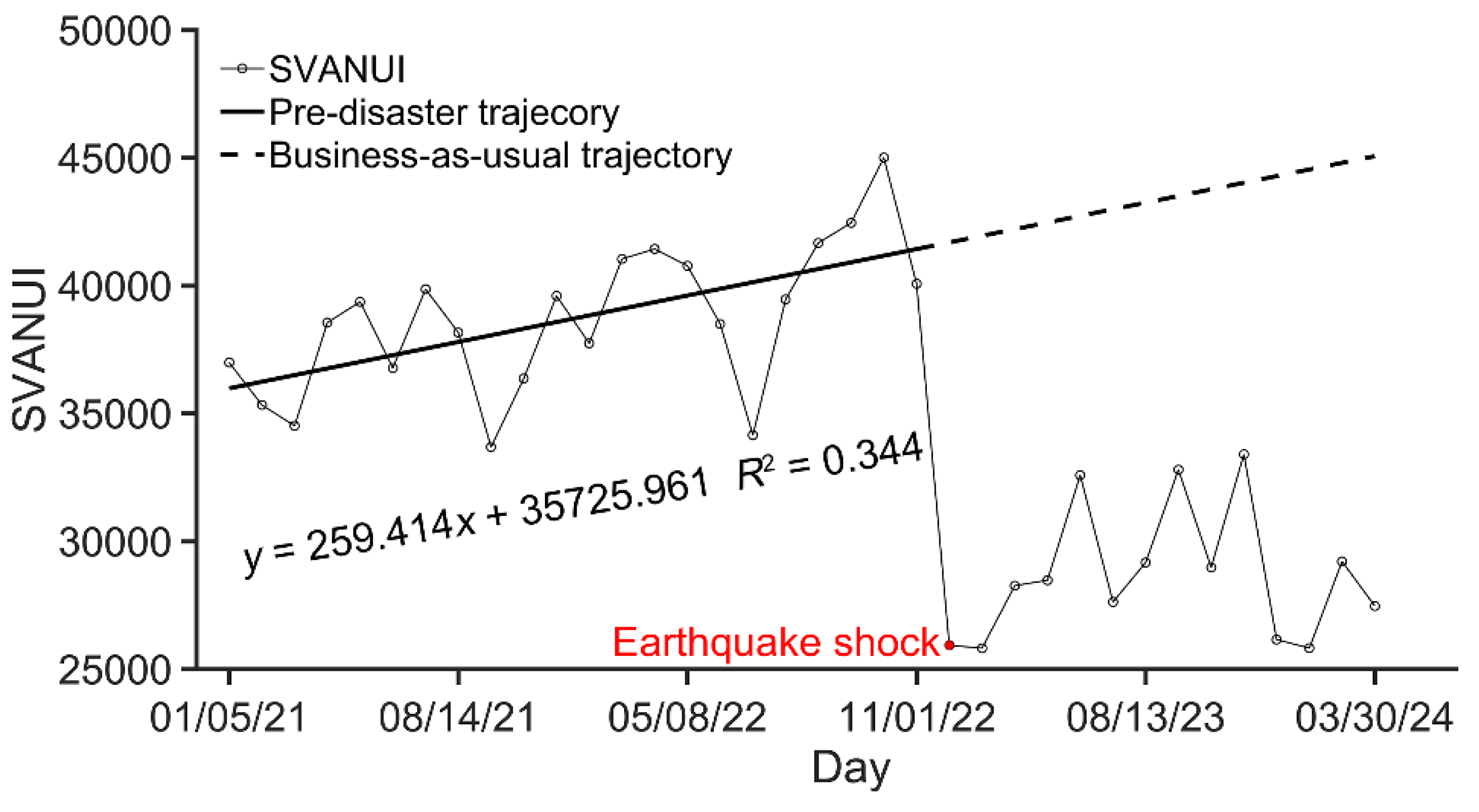

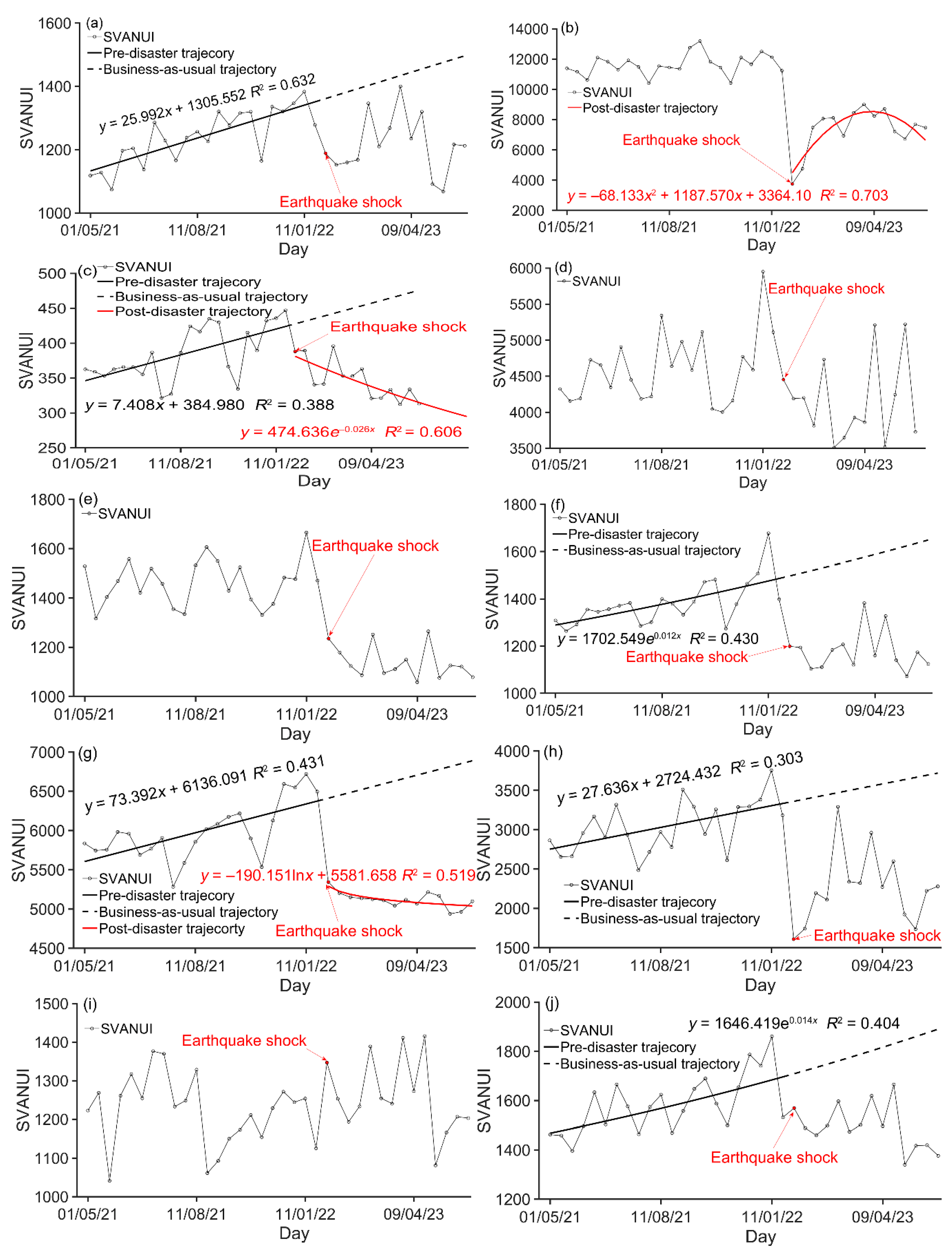

4.3. Assessment of Post-Earthquake Economic Recovery

5. Discussion

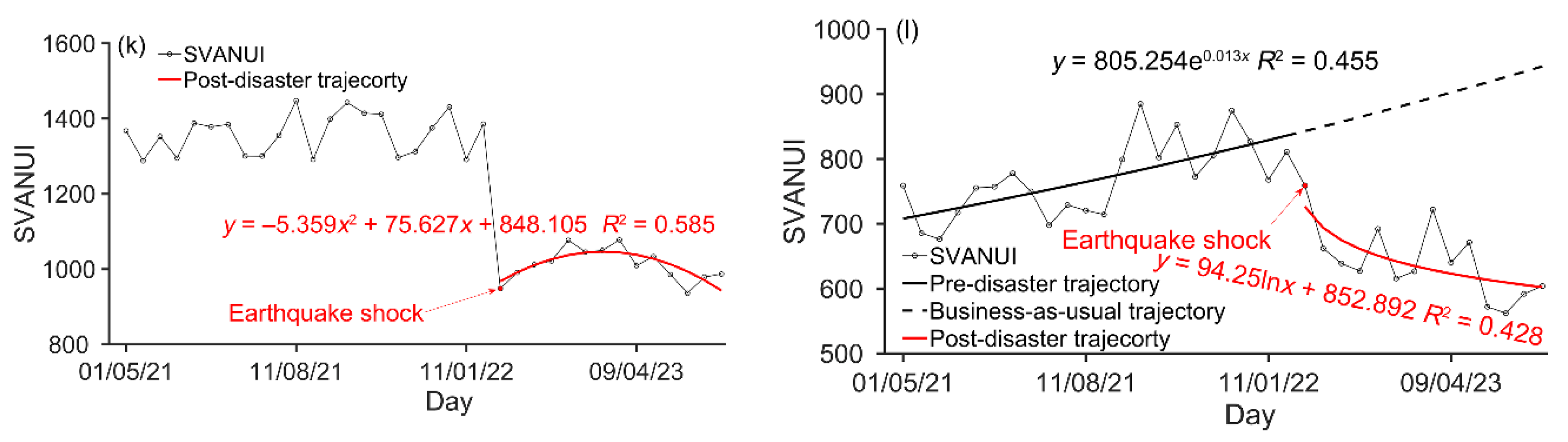

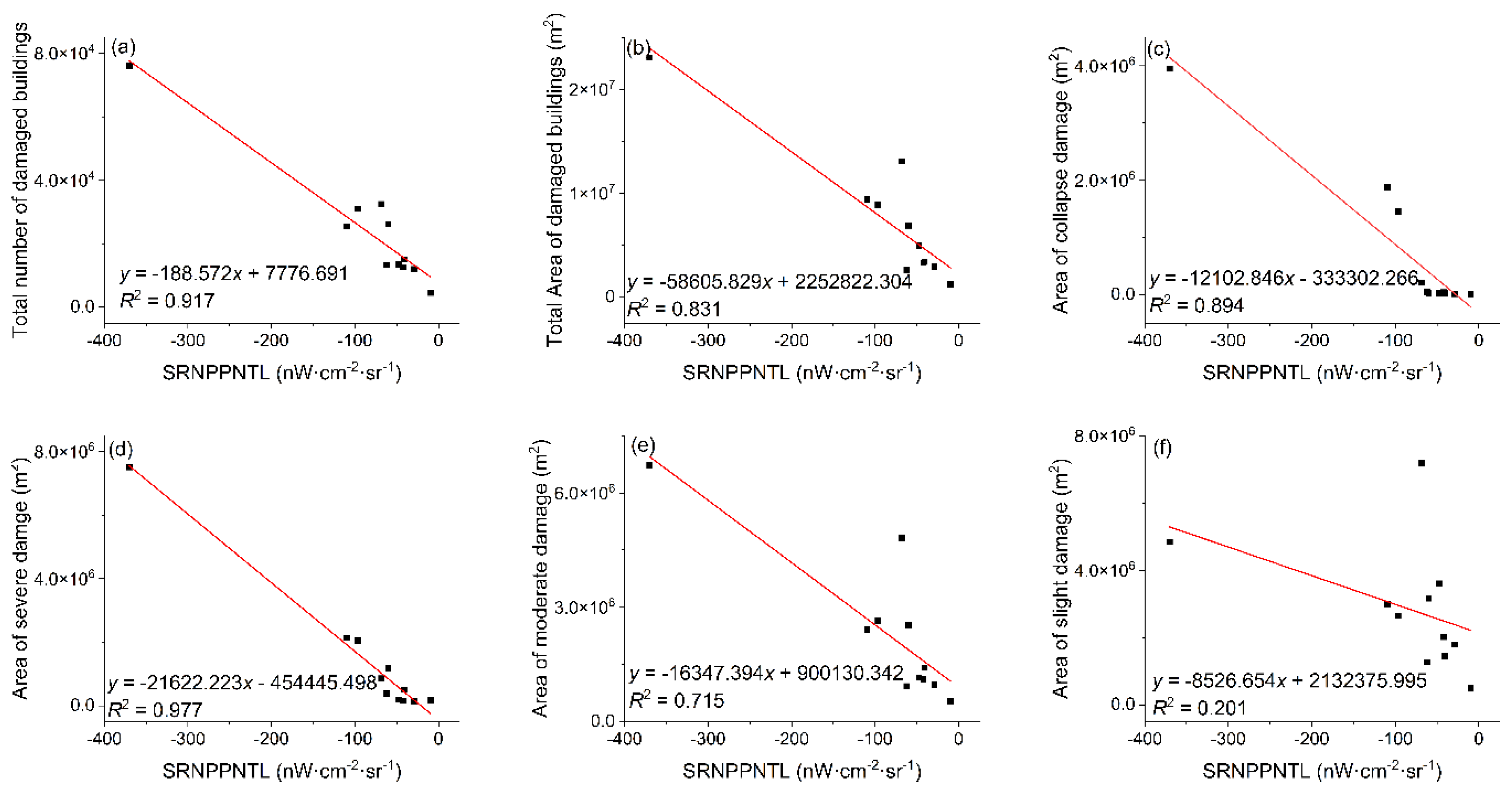

5.1. Relationship between Reduced NTLs and Damaged Buildings

5.2. A Comparative Analysis of the Performance of NPP-VIIRS and SDGSAT-1 NTL in Identifying Earthquake Damage

5.3. Coherence Analysis of Post-Earthquake Economic Recovery

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The M7.8 and M7.5 Kahramanmaraş Earthquake Sequence struck near Nurdağı, Turkey (Türkiye) on February 6, 2023. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/news/featured-story/m78-and-m75-kahramanmaras-earthquake-sequence-near-nurdagi-turkey-turkiye (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Taftsoglou, M.; Valkaniotis, S.; Papathanassiou, G.; Karantanellis, E. Satellite Imagery for Rapid Detection of Liquefaction Surface Manifestations: The Case Study of Türkiye–Syria 2023 Earthquakes. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezgi Güvercin, S. 2023 Earthquake Doublet in Türkiye Reveals the Complexities of the East Anatolian Fault Zone: Insights from Aftershock Patterns and Moment Tensor Solutions. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2024, 95, 664–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One year after Türkiye’s Earthquakes, Recovery Takes Many Forms. Available online: https://www.undp.org/eurasia/stories/one-year-after-turkiyes-earthquakes-recovery-takes-many-forms (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Gu, J.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, J.; He, X. Advances in Rapid Damage Identification Methods for Post-Disaster Regional Buildings Based on Remote Sensing Images: A Survey. Buildings 2024, 14, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniello, V.; Piscini, A.; Bignami, C.; Anniballe, R.; Stramondo, S. Earthquake Damage Mapping by Using Remotely Sensed Data: the Haiti Case Study. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2017, 11, 016042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yang, W.; Liu, X.; Sun, G.; Liu, J. Using High-Resolution UAV-borne Thermal Infrared Imagery to Detect Coal Fires in Majiliang Mine, Datong Coalfield, Northern China. Remote Sen. Lett. 2018, 9, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptman, L.; Mitsova, D.; Briggs, T.R. Hurricane Ian Damage Assessment Using Aerial Imagery and LiDAR: A Case Study of Estero Island, Florida. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Shan, J. A Comprehensive Review of Earthquake-Induced Building Damage Detection with Remote Sensing Techniques. ISPRS J. Photogrmm. 2013, 84, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, Y.; Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. BDHE-Net: A Novel Building Damage Heterogeneity Enhancement Network for Accurate and Efficient Post-Earthquake Assessment Using Aerial and Remote Sensing Data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Wu, J.; Yao, J.; Zhu, H.; Gong, A.; Yang, J.; Hu, L.; Mo, F. A Deep Learning Application for Building Damage Assessment Using Ultra-High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery in Turkey Earthquake. Int. J. Disast. Risk Sc. 2023, 14, 947–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haciefendioglu, K.; Başaga, H.B.; Kahya, V.; Ozgan, K.; Altunişik, A.C. Automatic Detection of Collapsed Buildings after the 6 February 2023 Türkiye Earthquakes Using Post-Disaster Satellite Images with Deep Learning-Based Semantic Segmentation Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Xiu, H.; Matsuoka, M. Backscattering Characteristics of SAR Images in Damaged Buildings Due to the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Park, S.-E.; Lee, S.-J. Detection of Damaged Buildings Using Temporal SAR Data with Different Observation Modes. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Feng, G.; He, L.; Xiong, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, X.; Wei, J. Three-Dimensional Deformation of the 2023 Turkey Mw 7.8 and Mw 7.7 Earthquake Sequence Obtained by Fusing Optical and SAR Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Feng, D.; Wu, G. InSAR-Based Rapid Damage Assessment of Urban Building Portfolios Following the 2023 Turkey Earthquake. Int. J. Disast. Risk Re. 2024, 103, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, G.; He, L.; An, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, W.; Li, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Evaluating Urban Building Damage of 2023 Kahramanmaras, Turkey Earthquake Sequence Using SAR Change Detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Hu, X.; Song, Y.; Xu, S.; Song, X.; Fan, X.; Wang, F. Intelligent Assessment of Building Damage of 2023 Turkey-Syria Earthquake by Multiple Remote Sensing Approaches. npj Nat. Hazards 2024, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Seto, K.C.; Zhou, Y.; You, S.; Weng, Q. Nighttime Light Remote Sensing for Urban Applications: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2023, 202, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Li, W.; Cui, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q. High-Spatial-Resolution Nighttime Light Dataset Acquisition Based on Volunteered Passenger Aircraft Remote Sensing. IEEE T. Geosci. Remote, 2022, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Liu, X.; Liao, S.; Jia, P. The Modified Normalized Urban Area Composite Index: A Satelliate-Derived High-Resolution Index for Extracting Urban Areas. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, R. The Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Regional Development in Shandong Province of China from 2012 to 2021 Based on Nighttime Light Remote Sensing. Sensors 2023, 23, 8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yu, L.; Yin, J.; Xi, M. Impact of Population Density on Spatial Differences in the Economic Growth of Urban Agglomerations: The Case of Guanzhong Plain Urban Agglomeration, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-L.; Liang, P.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Z.-Q. Multi-Scale Dynamic Analysis of the Russian–Ukrainian Conflict from the Perspective of Night-Time Lights. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Han, J.; Fan, K.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Fu, J. A Cost-Effective Earthquake Disaster Assessment Model for Power Systems Based on Nighttime Light Information. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Li, X.; Gong, Y.; Belabbes, S.; Dell'oro, L. Estimating Natural Disaster Loss Using Improved Daily Night-Time Light Data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2023, 120, 103359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Chen, Y.; Liang, L.; Gong, A. Post-Earthquake Night-Time Light Piecewise (PNLP) Pattern Based on NPP/VIIRS Night-Time Light Data: A Case Study of the 2015 Nepal Earthquake. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Chen, X. Long-Term Resilience Curve Analysis of Wenchuan Earthquake-Affected Counties Using DMSP-OLS Nighttime Light Images. IEEE J-Stars. 2021, 14, 10854–10874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Z. Evaluation of Earthquake Disaster Recovery Patterns and Influencing Factors: a Case Study of the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. All Earth, 2023, 35, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Liao, S.; Hu, W. Assessment of Economic Recovery in Hebei Province, China, under the COVID-19 Pandemic Using Nighttime Light Data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Shao, G.; Tang, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Liu, L. Quantifying Spatiotemporal Changes in Human Activities Induced by COVID-19 Pandemic Using Daily Nighttime Light Data. IEEE J-Stars, 2021, 14, 2740–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, G.; Mu, X.; Xie, D.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. Human Activity Changes During COVID-19 Lockdown in China—A View from Nighttime Light. GeoHealth, 2022, 6, e2021GH000555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Q.; Hu, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Rapid Assessment of Disaster Damage and Economic Resilience in Relation to the Flooding in Zhengzhou, China in 2021. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 13, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Ma, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Yu, B. The Changes in Nighttime Lights Caused by the Turkey-Syria Earthquake Using NOAA-20 VIIRS Day/Night Band Data. Remote. Sens. 3438; 15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Cao, H.; Gong, Y. Turkey-Syria Earthquake Assessment Using High-Resolution Night-time Light Images. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University, 2023, 48, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar]

- Hatay Province. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hatay_Province#Geography (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- 2023 Turkey–Syria Earthquakes. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2023_Turkey%E2%80%93Syria_earthquakes#cite_note-TRToll9FEB-104 (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Global Rapid Post-Disaster Damage Estimation (GRADE) Report: February 6, 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes–Türkiye Report (English). Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099022723021250141/pdf/P1788430aeb62f08009b2302bd4074030fb.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Alahmadi, M.; Mansour, S.; Dasgupta, N.; Abulibdeh, A.; Atkinson, P.M.; Martin, D.J. Using Daily Nighttime Lights to Monitor Spatiotemporal Patterns of Human Lifestyle under COVID-19: The Case of Saudi Arabia. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Level-1 and Atmosphere Archive & Distribution System Distributed Active Archive Center. Available online: https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/search/j (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- EOG Nighttime Light. Available online: https://eogdata.mines.edu/nighttime_light/monthly/v10/ (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- SDGSAT-1 Open Science Program. Available online: https://www.sdgsat.ac.cn/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Zhao, Z.; Qiu, S.; Chen, F.; Chen, Y.; Qian, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhang, Y.; Khoramshahi, E.; Qiu, Y. Vessel Detection with SDGSAT-1 Nighttime Light Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Dou, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Fu, B.; Li, X.; Zou, Z.; Liang, D. SDGSAT-1: The World's First Scientific Satellite for Sustainable Development Goals. Sci. Bull. 2022, 68, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- After Three Days and Two nights of Rescue, Hechi, Guangxi mountain fire has been completely extinguished (in Chinese). Available online: http://news.cnhubei.com/content/2024-02/23/content_17454359.html (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Firefighters are Trying Their Best to Extinguish a Mountain Fire in Jinchengjiang District, Hechi, Guangxi (in Chinese). Available online: https://news.sina.com.cn/c/2023-02-28/doc-imyiepni8106015.shtml (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- What We Know About the Earthquake in Turkey and Syria. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/10/world/middleeast/earthquake-turkey-syria-toll-aid.html (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- A Month Since the Devastating Earthquake in Turkey. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2023/03/photos-month-devastating-earthquake-turkey/673317 (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- ’People are terrified’: Despair and Fear among Ruins of Göksun. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/feb/07/goksun-residents-struggle-to-survive-after-turkish-earthquake (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- MODIS Vegetation Index User’s Guide. Available online: https://measures.arizona.edu/documents/MODIS/MODIS_VI_UsersGuide_09_18_2019_C61.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Microsoft Global ML Building Footprints. Available online: https://github.com/microsoft/GlobalMLBuildingFootprints?tab=readme-ov-file#readme (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- WorldPop Population Counts. Available online: https://github.com/microsoft/GlobalMLBuildingFootprints?tab=readme-ov-file#readme (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Download GADM Data (Version 4.1). Available online: https://gadm.org/download_country.html (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- M7.8 2023 Turkey EQ Building Damage (last updated Mar. 9, 2023). Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=86941dbff14e450bbe3f89897373c59a (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- El-naggar, A.M. Determination of Optimum Segmentation Parameter Values for Extracting Building from Remote Sensing Images. Alex. Eng. J. 2018, 57, 3089–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Shao, G.; Tang, L.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Rapid Assessment of a Typhoon Disaster Based on NPP-VIIRS DNB Daily Data: The Case of an Urban Agglomeration along Western Taiwan Straits, China. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerler, R.; Cao, C.; Xie, B.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, K.; Xu, M.; Lu, Y. Cross Reference of GDP Decrease with Nighttime Light Data via Remote Sensing Diagnosis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Luo, N.; Hu, C. Detection of County Economic Development Using LJ1-01 Nighttime Light Imagery: A Comparison with NPP-VIIRS Data. Sensors 2020, 20, 6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, S.; You, X.; Yang, C.; Wang, C.; Lin, J.; Wu, W.; Yu, B. New Nighttime Light Landscape Metrics for Analyzing Urban-Rural Differentiation in Economic Development at Township: A Case Study of Fujian Province, China. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 150, 102841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liao, S.; Liu, W. Assessment of Post-Pandemic Economic Recovery in Beijing, China, Using Night-Time Light Data. Remote Sen. Lett. 2024, 15, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM: 2023 Earthquakes Displacement Overview - Türkiye (March 2023). Available online: https://reliefweb.int/attachments/a064c286-3a66-4520-8848-08d988b3fbc0/2023%20Earthquakes%20Displacement%20Overview.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Turkey earthquake: Why Reconstruction Could Miss Erdogan's Goal. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkey-earthquake-why-reconstruction-could-miss-erdogans-goal-2023-10-13/ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Earthquakes Hit Manufacturing in Southern Provinces: Report. https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/earthquakes-hit-manufacturing-in-southern-provinces-report-190884. (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Before and After: Devastation Caused by Turkey Earthquake in Hatay- in Pictures. Available online: https://www.thenationalnews.com/mena/2024/02/06/before-and-after-devastation-caused-by-turkey-earthquake-in-hatay-in-pictures/#:~:text=On%20February%206%20last%20year,thousands%20of%20residents%20and%20refugees (accessed on 3 July 2024).

| Data type | Data Description | Period | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPP-VIIRS VNP46A1 DNB NTL |

Pre- and post-earthquake daily NTL data | August 25, 2022, and February 12, 2023 | Assessment of potential damage from earthquake disaster |

| Cloud-free DNB NTL data | January 2021 – March 2024 | Assessment of post-earthquake economic recovery | |

| SDGSAT-1 GIU NTL | Daily NTL data for the B2 band | August 22, 2022, and February 12, 2023 | Assessment of potential damage from earthquake disaster |

| MOD13A1 | Version 6 16-day EVI | 2021 – 2023 | Calibration of daily NTL data |

| Microsoft building footprint | Vectorized building outline | 2014 – 2022 | Statistics on earthquake-damaged buildings |

| WorldPop demographics | Demographics in GeoTIFF format | 2020 | Statistics on earthquake-affected populations |

| Building Damage Map | Building damage map in Hatay Province, Turkey derived from damage proxy maps | Last updated on May 9, 2023 | Validation of NTL-identified building damage |

| Administrative divisions | Administrative boundaries for 12 districts in Hatay Province, Turkey | 2022 | Assessment of post-earthquake economic recovery over the districts |

| Data type | Class | CE | OE | OA | KC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPP-VIIRS | Damage | 11.58% | 14.29% | 86.21% | 0.72 |

| No damage | 16.23% | 13.21% | |||

| SDGSAT-1 | Damage | 8.67% | 59.69% | 65.66% | 0.34 |

| No damage | 42.39% | 4.50% |

| Data type | Damaged level | Linear correlation equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPP-VIIRS | Severe | y = –40716.75x – 352264.96 | 0.99 |

| Moderate | y = –7417.52x – 23663.28 | 0.74 | |

| Slight | y = –15922.43x + 447060.95 | 0.13 | |

| SDGSAT-1 | Severe | y = –159.51x – 538358.85 | 0.98 |

| Moderate | y = 115.80x + 835291.70 | 0.02 | |

| Slight | y = –695.06x + 162020.71 | 0.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).