1. Introduction

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease causing a health problem throughout the world, especially in countries with tropical and subtropical climates with high rainfall.[

1,

2] Leptospirosis is caused by infection with pathogenic

Leptospira species.[

3] Leptospirosis disease could transmit from animals to humans or vice versa directly or indirectly.[

2,

4] Direct transmission occurs when Leptospira bacteria from infected animal bodies, tissues, or urine enter the human body. Indirect transmission occurs when animals infected with Leptospira bacteria spread bacteria through the contaminated environment, such as soil, water, plants, and mud.[

4]

The annual estimation of leptospirosis globally was 1.03 million cases with 58,900 deaths. Southeast Asia is one of the endemic areas for leptospirosis.[

5,

6] One of the countries is Indonesia. Most areas in Indonesia have a tropical climate with high rainfall and humidity, so they have the potential to be a breeding ground for

Leptospira bacteria.[

7].

Leptospirosis is endemic in several areas of Indonesia and has become a health problem for many years [

8]. The mortality rate for leptospirosis in Indonesia is high, reaching 2.5-16.45% [

9]. In 2018, Indonesia reported 895 cases of leptospirosis, with the highest contributed by Central Java (427, 47.7%) and 89 deaths (20.8%).[

8] The Klaten Regency is an endemic area of leptospirosis in Central Java Province. In 2018, Klaten Regency was ranked second in the number of leptospirosis cases in Central Java, with an Incidence Rate of leptospirosis in January-June of 4.18 per 100,000 population, exceeding the national target of 3 per 100,000 population [

10].

In leptospirosis, environmental factors are very influential in the incidence of the disease. The interaction between the agent and the host occurs in the environment. Agent, host, and environment can produce habitats and bionomies that influence each other. Environmental conditions, including abiotic and biotic environmental factors, can also contribute to the incidence of leptospirosis.[

8,

11,

12,

13].

Mapping the leptospirosis disease using a Geographic Information System (GIS) will provide an overview of the areas at risk. Therefore, this study aims to map the distribution of leptospirosis incidence and describe the abiotic and biotic environmental factors with the incidence of leptospirosis spatially in Klaten Regency, Central Java, Indonesia, in 2018.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Type and Design

This study uses descriptive observational research with a cross-sectional approach. This research was conducted in June – August 2019 in Klaten Regency.

2.2. Population and Research Sample

The population in this study were leptospirosis sufferers recorded in all public health centers and hospitals in the Klaten Regency in 2018, as many as 67 patients. All members in the population were used as research samples with inclusion criteria: residing in the Klaten Regency. While the exclusion criteria in this study were: did not want to be a respondent, the respondent moved house, and was unable to be found. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the number of research samples was 59 leptospirosis patients.

2.3. Data sources, Data Processing and Analysis

In this study, the authors use primary data and secondary data. The primary data in this study were taken by interview and direct observation methods. Interviews and observations were conducted by filling out questionnaires and observation sheets related to biotic environmental factors. Interviews and observations were conducted after leptospirosis patients agreed to be respondents and signed the informed consent form. Secondary data in the form of rainfall and altitude data were obtained from the Klaten Public Works and Spatial Planning Office; temperature and humidity data were obtained from online data from the Meteorology and Geophysics Agency of Mlati Station; data on leptospirosis cases from January to December 2018 in Klaten Regency and digital SHP map data in Klaten Regency were obtained from the Agency for Regional Development and the Klaten Public Works and Spatial Planning Office. The data were then processed using software like Microsoft Excel, SPSS, and Arc GIS 10.3. Data processing includes editing, coding, entry, cleaning, and tabulating data. Data analysis consisted of univariate analysis and spatial analysis.

2.4. Ethical Approval

This study has obtained ethical clearance from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Faculty of Public Health, Diponegoro University, No. 246/EA/KEPK-FKM/2019. Informed consent was approved by the respondents prior to conducting interviews and observations.

3. Results

3.1. Abiotic Enviromental Factors

3.1.1. Waste Disposal Facility

All respondents had a garbage dump (100%), around 93.2% of respondents had a trash can inside the house, but only a few had a trash can outside the house (40.7%). Besides, most of the respondents had garbage piled up (74,6%), waterproof trash cans (91,5%), and open trash cans (83,1%). Most of them threw the trash in the yard (59,3%) (

Table 1).

The study results show that more respondents with good waste disposal facilities, 38 (64.4%) than those with poor disposal facilities, were 21 people (35.6%). The average distance between the trash can and the respondent's house was 3.1 meters (

Table 1).

The spatial analysis of waste disposal facilities with leptospirosis incidence in the Klaten Regency in 2018 shows that respondents' waste disposal facilities were poor in several respondent areas (35.6%). The spatial distribution of leptospirosis cases and waste disposal facilities showed that inadequate waste disposal facilities spread in 18 villages out of 52 villages and one urban village. These areas include: Kranggan, Bengking, Pepe, Jombor, Kujon, Wonosari, Gamblegan, Jogosetran, Gumulan, Kalikotes, Mandong, Karangdowo, Karangpakel, Rejoso, Kalitengah, Birit, Trotok, and Kaligayam (

Figure 1).

3.1.2. Sewer Condition

Table 2 shows that more respondent had sewers were 34 people (57.6%). There were 14 respondents with poor categories (41.2%) who had gutters. Most of the respondents had open sewers (91.2%), rats passing through the ditches (73.5%), and rat holes in the gutter (52.9%) (

Table 2).

Based on the spatial analysis of sewer conditions and the incidence of leptospirosis in the Klaten Regency, it is shown that the presence of sewers can be a medium for the spread of leptospirosis disease. Based on the results of observations, it was shown that the rat holes in the ditches were in soil ditches that were not cemented. The condition of the sewers was poor in 13 villages out of 52 villages and 1 urban village, such as in Kranggan, Delanggu, Mranggen, Karanglo, Jogosetran, Karangpakel, Mandong, Plosowangi, Kraguman, Kragilan, Ngandong, Bugisan, and Kokosan (

Figure 2).

3.1.3. The Existence of The River

Based on table 3. reveals that as many as 32 respondents (52.2%) have a house close to the river <200 meters from the respondent's house (

Table 3).

The distribution of leptospirosis cases based on the presence of rivers in the Klaten Regency can be seen in

Figure 3. Most of the respondents' houses were located near the river at a distance of <200 meters. The distance of the river <200 meters from the respondent's house was spread over 31 villages and 1 urban village out of 52 villages and 1 urban village, which were Kokosan Village (52.8 m), Rejoso Village (3.7 m), Bakung Village (17.1 m), Ceporan Village (100 m), Towangsan Village (60.9 m), Kragilan Village (116.3 m), Ngandong Village (199.6 m), Plawikan Village (192.5 m), Nglinggi Village (72.7 m), Karanglo Village (106.8 m), Senden Village (39.4 m), Jebugan Village (75.5 m), Gumulan Village (25.5 m), Jomboran Village (172.9 m), Gamblegan Village (102 ,9 m), Kalikotes Village (136.4 m), Mayungan Village (27.1 m), Randulanang Village(140.3 m), Mlese Village (61,7 m), Canan Village (152 m), Trotok Village (79.3 m), Kaligayam Village (10 m), Karangpakel Village (17.8 m), Karangdowo Village (155.8-176.7 m), Kalitengah Village (39 m), Kadilanggon Village (164.2 m), Drono Village (104.2 m), Dalangan Village (20.9 m), Birit Village (96.8 m), Boto and Buntalan Villages (138, 2 m) (

Figure 3).

3.1.4. Flood History

Based on

Table 4. shows that fewer respondents experienced flooding, namely four respondents (6.8%), compared to respondents who did not experience flooding (91.5%) in 2018.

A spatial analysis of flood history with the incidence of leptospirosis in the Klaten Regency shows that floods occurred in 2018 in several villages in Klaten Regency. The history of flooding in the Klaten Regency within one year reached only a few numbers of respondents' houses, spread over four villages from 52 villages and one urban village. Based on the map, the history of flooding was in the villages of Mlese, Canan, Kaligayam, and Karangpakel. Puddles of water during floods can be a medium for the spread of

Leptospira bacteria (

Figure 4).

3.1.5. Rainfall, Air Temperature, Humidity, and Altitude

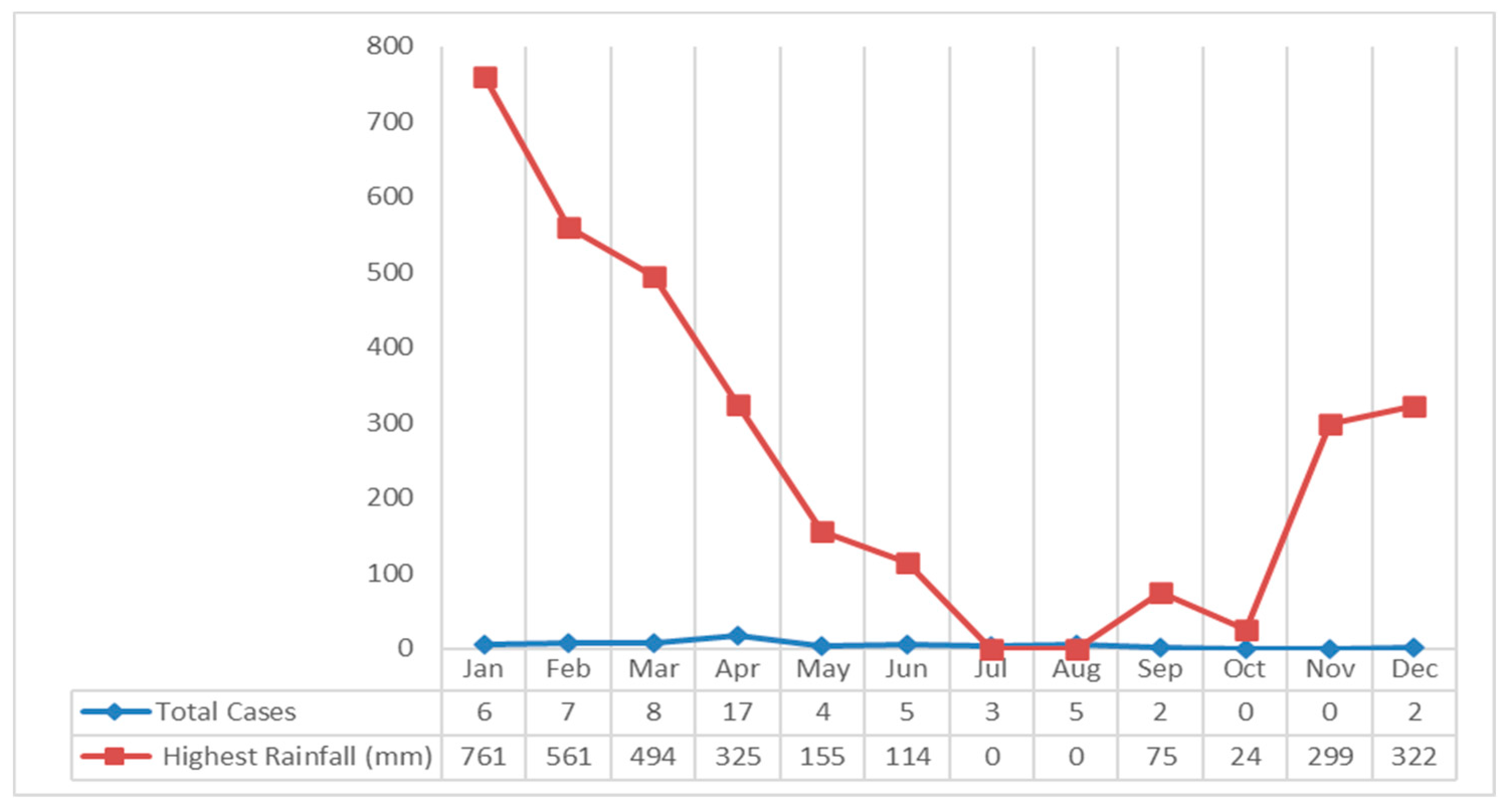

The study results showed that the rainfall in Klaten Regency tends to fall every month.

The highest rainfall occurred in January 2018 at 761 mm, and the lowest occurred in October at 24 mm. If it is associated with leptospirosis cases, most cases occurred in April with 325 mm of rainfall which was included in the high category (

Figure 5).

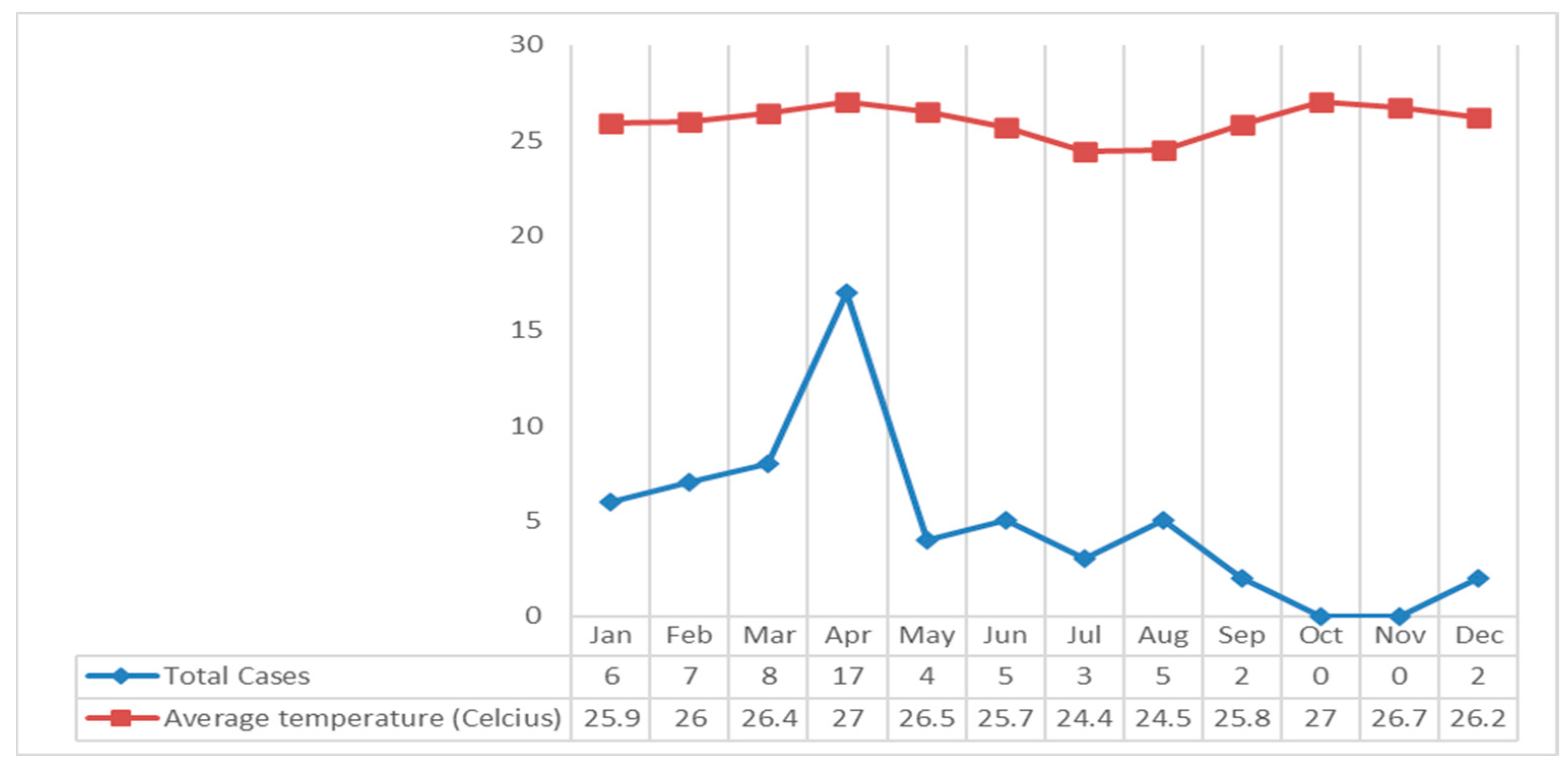

Based on

Figure 6 describes that the air temperature in the Klaten Regency fluctuates. The highest air temperature occurred in April and October 2018, 27

0C, and the lowest air temperature occurred in July at 24.4

0C. If it is associated with leptospirosis cases, most cases occurred in April, with an average air temperature of the highest in 2018 at 27

0C (

Figure 6).

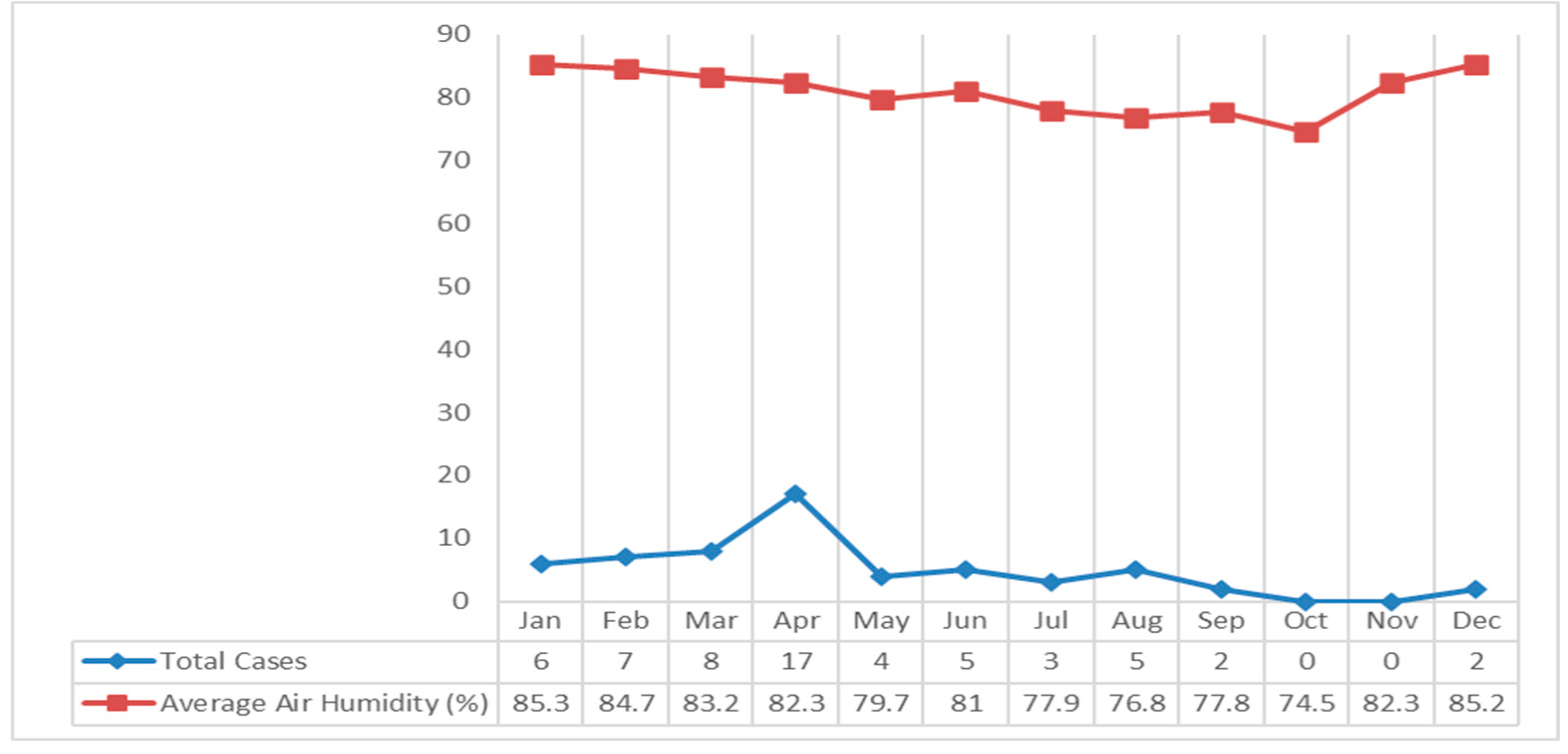

The average air humidity in Klaten Regency fluctuates. The highest average air humidity occurred in January 2018 at 85.3%, and the lowest in October at 74.5%. If it is associated with leptospirosis cases, most cases occurred in April with an average humidity of 82.3% (

Figure 7).

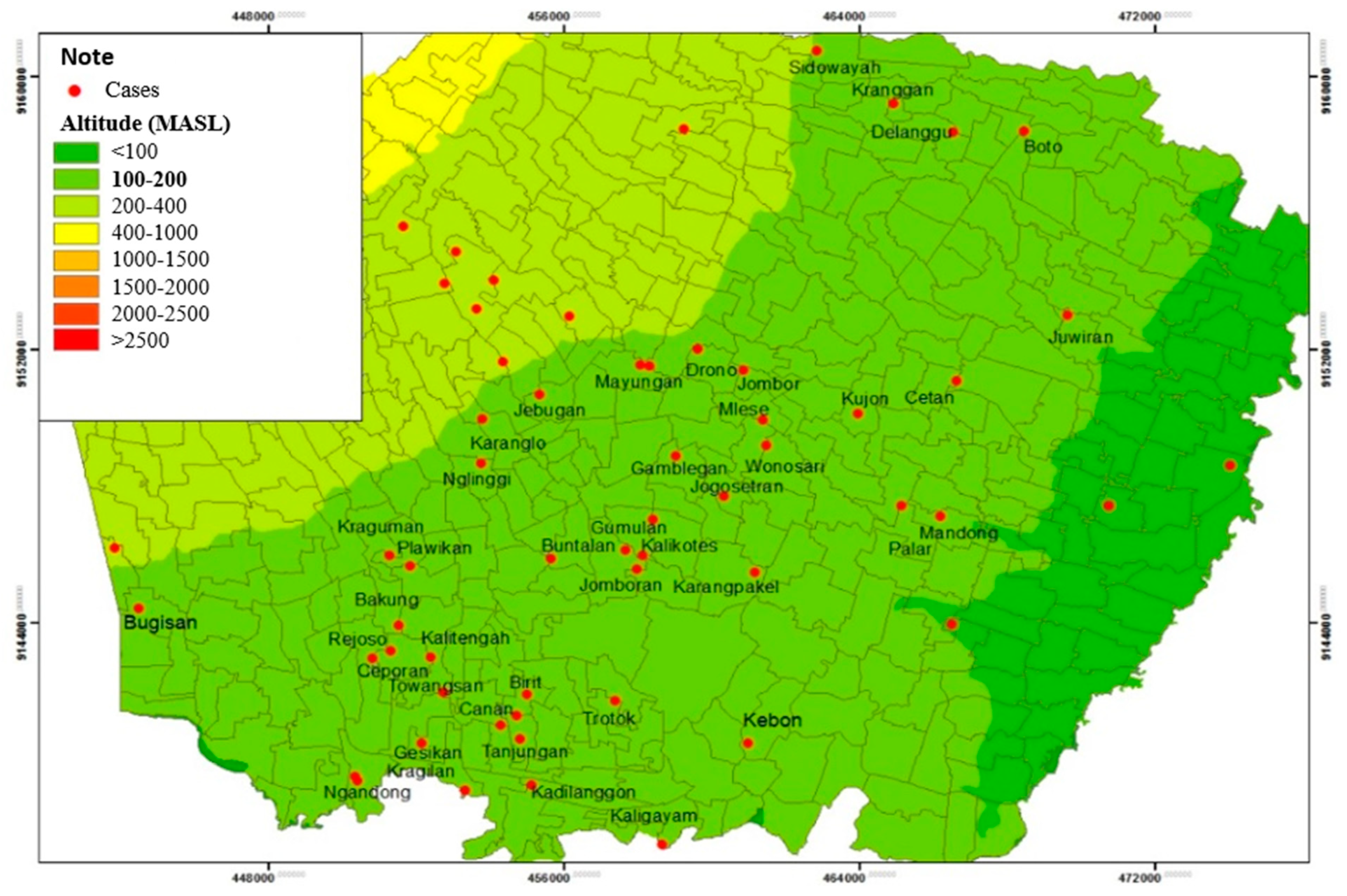

Based on the results of the study, the most cases of leptospirosis were at an altitude of 100-200 Meters Above Sea Level (MASL), as many as 47 respondents (79.7%) (

Table 5).

The spatial distribution shows that Leptospirosis cases in Klaten Regency spread at an altitude of < 100 MASL, 100-200 MASL, and 200-400 MASL. Most respondents were located at an altitude of 100-200 MASL, spread over 40 villages from 52 villages and one urban village, which were Bugisan Village (186 MASL), Ngandong Village (139-145 MASL), Gamblegan Village (161 MASL), Wonosari Village (149 MASL), Kujon Village (148 MASL), Cetan Village (143 MASL), Jombor Village (188 MASL), Mlese village (150 MASL), Drono village (190 MAS), Mranggen village (270-307 MASL), Karanglo village (153 MASL), Jebugan village (143 MASL), Juwiran village (114 MASL), Boto village (151 MASL), Delanggu village (170 MASL), Kranggan (176 MASL), Sidowayah (205 MASL), Kragilan (131 MASL), Gesikan (144 MASL), Towangsan (149 MASL), Ceporan (158 MASL), Canan (144 MASL), Tanjungan (138 MASL), Kadilanggon (112 MASL), Kaligayam (148 MASL), Birit (143 MASL), Trotok (130 MASL), Kebon (129 MASL), Rejoso (160 MASL), Bakung (164 MASL), Plawikan (174 MASL), Kraguman (183 MASL), Buntalan (173 MASL), Jomboran (140-158 MASL), Karangpakel (134 MASL), Kalikotes (163 MASL), Gumulan (151 MASL), Palar (135 MASL), Mandong (177 MASL), and Nglinggi (200 MASPL) (

Figure 8).

3.2. Biotic Environmental Factors

3.2.1. Presence of Rats

The following is table of nest rats’ existence in the house respondent:

Based on

Table 6, there were nest rats all over house respondents (100.0%). A total of 57 respondents (96.6%) had seen rats inside the home, and all respondents (100.0%) had ever seen a nest rat outside the home. Common types of rats seen by respondents were roof rats and wirok rats. Based on the observation in and around the respondents' houses, some signs of rats included dirt, bites, and rat holes. The following is the distribution of leptospirosis and the presence of nest rats based on village / urban village:

Based on spatial analysis, nest rats exist throughout house respondents, which were in 52 villages and 1 urban village spread over 20 sub-districts. They were Bugisan, Kokosan, Rejoso, Bakung, Ceporan, Gesikan, Towangsan, Kragilan, Ngandong, Plawikan, Nglinggi, Karanglo, Senden, Jebugan, Kraguman, Gumulan, Jomboran, Gamblegan, Jogosetran, Kalikotes, Mayungan, Pepe, Jemawan, Mranggen, Randulanang, Bengking, Sidowayah, Kranggan, Delanggu, Juwiran, Mlese, Jombor, Cetan, Kujon, Plosowangi, Mandong, Palar, Wonosari, Canan, Birit, Trotok, Kaligayam, Kebon, Karangpakel, Karangdowo, Demangan, Kalitengah, Kadilanggon, Tanjungan, Drono, Dalangan, Boto villages, and Buntalan urban village (

Figure 9).

3.2.2. Presence of Pets-at Risk

The following is table of presence of pets-at risk at respondents’ home:

The

Table 7 shows that most respondents did not have an animal pet at risk (67.8%) than those who had (32.2%). Cats were mostly found in the respondent's houses (42.1%) (

Table 7). The following is the distribution of leptospirosis and the presence of animal pets at risk based on village / urban village:

Figure 10 reveals that pets are at risk in fewer respondents. The animal type pet risk owned by most respondents were cats, goats, and cows. The existence of animals at risk was spread over 16 villages and one urban village, such as Sidowayah Village, Boto Village, Mranggen Village, Jemawan village, Pepe Village, Drono Village, Karanglo Village, Juwiran Village, Jogosetran village, Palar Village, Karangpakel village, Karangdowo Village, Trotok Village, Birit Village, Tanjungan village, Gesik Village, and Kaligayam Village.

3.2.3. Vegetation Type

The following is the table of existence of vegetation around house respondent:

Table 8 reveals that the most vegetation type around house respondents was tree shade (93.2%). Respondents mostly had ≥ 3 vegetations (79.7%). The average distance between vegetation to house respondents was 4.5 meters (

Table 8). The following is the distribution of leptospirosis and the presence of vegetation by village / urban village:

Based on

Figure 11, ≥ 3 vegetations types spread over 42 villages from 52 villages and 1 urban village such as Bugisan Village with 3 types vegetation, Kokosan with 5 types vegetation, Rejoso with 4 types vegetation, Bakung with 4 types vegetation, Towangsan with 4 types vegetation, Kragilan with 3 types vegetation, Ngandong with 5 types vegetation, Plawikan with 3 types vegetation, Nlinggi with 3 types vegetation, Karanglo with 3 types vegetation, Senden with 4 types vegetation, Jebugan with 4 types vegetation, Kraguman with 4 types vegetation, Gumulan with 6 types vegetation, Jomboran with 4 types vegetation, Gamblegan with 4 types vegetation, Kalikotes with 4 types vegetation, Mayungan with 5 types vegetation, Jemawan with 4 types vegetation, Mranggen with 4 types vegetation, Randunang with 4 types vegetation, Bengking with 4 types vegetation, Kranggan with 3 types vegetation,Juwiran with 3 types vegetation, Mlese with 4 types vegetation, Cetan with 3 types vegetation, Kujon 3 types vegetation, Plosowangi with 4 types vegetation, Mandong with 3 types vegetation, Palar with 3 types vegetation, Wonosari with 4 types vegetation, Canan with 4 types vegetation , Birit with type vegetation, Trotok with 5 types vegetation, Kaligayam with 6 types vegetation, Kebon with 3 types vegetation, Karangpakel with 7 types vegetation, Karangdowo with 3 types vegetation, Demangan with 4 types vegetation, Kalitengah with 4 types vegetation, Kadilanggon with 3 types vegetation, and Tanjungan with 3 types vegetation (

Figure 11).

4. Discussion

Recent research shows that most of the respondents have good disposal facilities. This result is similar to a previous study that showed 81.1% of the residential area in Si Sa Ket, Thailand, had garbage disposals.[

14]. However, the majority of the cases had garbage piled up inside their house. This condition led to rats in the trash in some of their homes. Poor house sanitation is a risk factor for leptospirosis, and outbreak. [4,15] Beside, the results of this study indicate that the average distance between the outside garbage and the respondent's house is 3.1 meters. The increasing rat population can be affected by garbage around the house.[

4]

Based on interviews and observations, many respondents have open gutters. Rats often pass through sewers, with rat holes in the gutters. The above conditions are closely related to risk factors for leptospirosis. Mice that pass-through water can spread

Leptospira bacteria through rat urine. Sewers allow rats to migrate to other areas for shelter and food, including roads to enter people's homes through drainage.[

16] The research in the Kodagu district of southern India revealed that proximity to an open sewer was associated with leptospirosis (p-value= 0.02) with adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] = 4.9 (CI: 1.2-19.1).[

17]

Based on the study's results, it was shown that respondents with poor sewer conditions were almost half of the total respondents. Sewer conditions are a risk factor for leptospirosis infection.[

18] In contrast with study in the highlands of Ponorogo Regency, Province of East Java, Indonesia showed that 21 (75%) cases had eligible sewerage.[

4]

Based on the results of the study showed that most cases of leptospirosis were around rivers with river buffers <200 meters. The closest distance from the river is 3.7 meters. Based on observations, many rat holes were seen on the river bank. When the river water rises, the rats come out of the hole and enter people's houses. Based on the study results, although the respondents' location was close to the river, only a small number of respondents had experienced flooding and were in the respondent's area. The overflow of river water found in a small number of respondents only flooded the streets around the house. However, the puddle can potentially spread

Leptospira bacteria in the environment. Many leptospirosis outbreaks occur during heavy rains and floods.[

18] The existence of conditions after a flood allows people to come into direct contact with polluted water and is favourable for developing infection.[

19] From Ratnaningsih's research in Kalitengah village, Wedi District, Klaten Regency, it was found that 2 rats of the Rattus tanezumi species were positive for Leptospira bacteria out of 17 rats caught. Rattus tanezumi habitats close to humans in residential areas can be a source of Leptospira transmission and can spread to humans and other environments.

The highest number of leptospirosis cases occurred in April, with 325 mm of rainfall in the high category. The high rainfall in Klaten Regency led to puddles around the house, which caused the gutters to overflow and inundate the surrounding streets. Based on data on average temperature and humidity each month, the average temperature is 27°C in April. The average air temperature is close to the optimal temperature for growth of leptospirosis, which is 28°C—30°C.[

20]. The recent study reveals that the average humidity is 82.3%. The average air humidity supports the growth of

Leptospira bacteria outside its host. In another study related to rainfall in Sri Lanka in 2008-2015, in which cases of leptospirosis occurred with an average annual rainfall of 2056, an average air temperature of 25

0C, and average humidity of 83.7% [

21]. The increases in the cases have been correlated with high rainfall, temperature, and relative humidity that support the survival of rodents and rodent densities, and the bacteria.[18,21–24]

Based on spatial analysis, nests were found in all respondents' houses. Respondents often see roof rats and shrew types in the house, while sewer and wirok rats are outside. This study was supported by revealing that most respondents had seen rats at home, with 62.7%.[

25] The rat's existence in the house was associated with leptospirosis incidence with a p-value of 0.050.[

4] Exposure to carrier rodents was related to the risk of disease transmission.[

26]

A study conducted in Pati in 2019 stated that the presence of rats was proven to be a risk factor for leptospirosis. The presence of rats in and around the house has a 4.51 times greater risk of infecting leptospirosis than the absence of rats.[27] The study results show that fewer respondents have pets than those who do not. Based on the spatial analysis, at-risk pets are present only in several areas. The most common pet owned by the respondents is a cat. A study conducted in Southern Chile in 2014 conveyed that Leptospira seropositive was found in cats. Animal habitat characteristics and some agricultural activities carried out by cat owners were risk factors associated with seropositivity.[

28]

Cats in all respondents' homes were allowed to roam inside and outside. Other pets owned by respondents are goats and cows. Cows and goats are in the stable. Sometimes it is placed in the garden and tied so that it does not wander into the streets or houses of residents. This study is in line with previous study showing almost a third of cases had pets or livestock.[

25] The study previously revealed that livestock ownership, cattle ownership, and the distance from the house to the cowshed were associated with the incidence of leptospirosis with p values of 0.004, 0.010, and 0.024, respectively. The odds Ration calculation of livestock ownership was 13,830 (with a 95% CI of 1,702–112,382).[

4] Infected animals can spread leptospirosis through direct urine, other non-salivary body fluids, or contaminated soil or water.[4,29] Having livestock or pets is one of the factors related to disease transmission.[

26,

30] Sharing habitat between animals allows leptospirosis transmission.[

30]

The results showed that the majority of respondents who live around their houses have three types of vegetation, with shade trees as the most common vegetation. Vegetation is also a habitat for rodents, for example, bushes and rice fields. Vegetation availability in the yard also allows rodents to enter the house through branches or twigs adjacent to the house by climbing.[

31] Abundant vegetation positively influences rodent abundance by providing food, a suitable breeding environment, and shelter.[32] A lot of vegetation cover can increase the persistence of the Leptospira spp.-free life stage because it is associated with lowering the ambient temperature, solar radiation, and increasing humidity.[

24,32]

This research had been attempted and carried out following scientific procedures, but there were still limitations. Firstly, air temperature and humidity data were obtained from the Yogyakarta Mlati station. Klaten Regency did not have a temperature and humidity monitoring station. The nearest air temperature and humidity monitoring stations are in Karanganyar and Adi Sumarmo Airport. Because of the incompleteness of the data in the nearest stations, the authors used Mlati station data under the direction of the Semarang Meteorology and Geophysics Agency. Besides, the abiotic data collection used secondary data, and the research design used descriptive study. This research was conducted in 2019, and there is the possibility that the environmental conditions of respondents have changed, whether they improve or get worse. However, Klaten Regency still had many cases with the highest prevalence and IR of leptospirosis in Central Java, namely 80 cases and 6/100,000 population, respectively, in 2022.[33]

5. Conclusions

The conclusion, the percentage abiotic factors included poor waste disposal facilities, poor gutter conditions, presence of rivers < 200 meters, and history of flooding are 35.6%; 41.2%; 54.2%, and 6.8%, consecutively. Most Leptospirosis occurred in April, with the highest rainfall of 325 mm, air temperature of 270C, humidity 82.3%, and altitude between 100-200 MASL. Based on biotic environmental factors, the presence of rat nests was found in all respondents' houses (100.0%), respondents who had pets at risk (32.2%), and the type of vegetation around the respondent's house three types (79.7%). Implementing the One Health approach is necessary to prevent and control zoonosis, including Leptospirosis incidence, through cross-sectoral collaboration, for example, in controlling rats in the Klaten Regency. The recommendations for further studies are the use of case-control as an analytical study design and direct measurements such as rainfall and altitude data, temperature, and humidity to produce more accurate data.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Dwi Sutiningsih: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration; Cintya Dipta Permatasari: Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Visualization, Project administration; Nur Azizah Azzahra: Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Alfonso J. Rodriquez-Morales: Review & Editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Faculty of Public Health, Diponegoro University (protocol code No. 246/EA/KEPK-FKM/2019 and approved on June 21, 2020).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was approved by the respondents prior to conducting interviews and observations.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We thanks to all respondents and officers in related institutions for the time.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Chadsuthi, S.; Chalvet-Monfray, K.; Geawduanglek, S.; Wongnak, P., & Cappelle, J. Spatial–temporal patterns and risk factors for human leptospirosis in Thailand, 2012–2018. Scientific Reports 2022, 12(1), 5066. [CrossRef]

- Rao, A. M. Rodent control a tool for prevention of leptospirosis - A success story on human leptospirosis with gujarat state. Journal of Communicable Diseases 2020, 52(3), 38–42. [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; Affendy, N. B.; Ramli, S. N. A.; Arif, M.; Raja, P.; Nagandran, E.; Renganathan, P.; Taib, N. M.; Masri, S. N.; Yuhana, M. Y.; Than, L. T. L.; Seganathirajah, M.; Goarant, C.; Goris, M. G. A., Sekawi, Z., & Neela, V. K. (2020). Leptospira interrogans and leptospira kirschneri are the dominant leptospira species causing human leptospirosis in central Malaysia. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14(3), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Notobroto, H. B., Mirasa, Y. A., & Rahman, F. S. (2021). Sociodemographic, behavioral, and environmental factors associated with the incidence of leptospirosis in highlands of Ponorogo Regency, Province of East Java, Indonesia. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 12(November), 100911.

- Gizamba, J. M., Paul, L., Dlamini, S. K., & Odayar, J. (2023). Incidence and distribution of human leptospirosis in the Western Cape Province, South Africa (2010-2019): A retrospective study. Pan African Medical Journal, 44(121), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kadir, M. A. A., Manaf, R. A., Mokhtar, S. A., & Ismail, L. I. (2023). Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Leptospirosis Hotspot Areas and Its Association with Hydroclimatic Factors in Selangor, Malaysia: Protocol for an Ecological Cross-sectional Study. JMIR Research Protocols, 12(e43712), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S., Sandai, D., Musa, S., Hoe, C., Riadzi, M., Lau, K., & Tag, T. (2012). Rapid diagnosis of leptospirosis by multiplex PCR. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 19(3), 9–16.

- Setyaningsih, Y., Bahtiar, N., Kartini, A., Pradigdo, S. F., & Saraswati, L. D. (2022). The presence of Leptospira sp. and leptospirosis risk factor analysis in Boyolali district. Journal of Public Leptospira sp. and leptospirosis risk factor analysis in Boyolali district. Journal of Public Health Research, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- Sofiyani, M., Dharmawan, R., & Murti, B. (2018). Risk factors of leptospirosis in Klaten, Central Java. Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health, 03(01), 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Central Java Provincial Health Office. (2018). Health Pocket Book. Central Java Provincial Health Office.

- Artus, A., Schafer, I. J., Cossaboom, C. M., Haberling, D. L., Galloway, R., Sutherland, G., Browne, A. S., Roth, J., France, V., Cranford, H. M., Kines, K. J., Pompey, J., Ellis, B. R., Walke, H., Ellis, E. M., Villarma, A., Carrillo, M., Delgado, D., Doyle, J., … Aponte, J. (2022). Seroprevalence, distribution, and risk factors for human leptospirosis in the United States Virgin Islands. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 16(11), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Naing, C., Reid, S. A., Aye, S. N., Htet, N. H., & Ambu, S. (2019). Risk factors for human leptospirosis following flooding: A meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE, 14(5), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Toemjai, T., Thongkrajai, P., & Nithikathkul, C. (2022). Factors affecting preventive behavior against leptospirosis among the population at risk in Si Sa Ket, Thailand. One Health, 14(May), 100399. [CrossRef]

- Masunga, D. S., Rai, A., Abbass, M., Uwishema, O., Wellington, J., Uweis, L., El Saleh, R., Arab, S., Onyeaka, C. V. P., & Onyeaka, H. (2022). Leptospirosis outbreak in Tanzania: An alarming situation. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 80, 104347. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Himsworth, C. G., Lee, M. J., & Byers, K. A. (2023). A systematic review of Rat Ecology in Urban Sewer Systems. Urban Ecosystems, 26(1), 223–232. [CrossRef]

- Arulmohi, M., Vinayagamoorthy, V., & R., D. A. (2017). Physical Violence Against Doctors: A Content Analysis from Online Indian Newspapers. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 42(1), 147–150. [CrossRef]

- Becirovic, A., Trnacevic, A., Rekic, A., & Dzafic, F. (2022). Floods Associated with Environmental Factors and Leptospirosis: Our Experience at Tuzla Canton, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Materia Socio Medica, 34(3), 193. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. M., Stull, J. W., & Moore, G. E. (2022). Potential Drivers for the Re-Emergence of Canine Leptospirosis in the United States and Canada. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 7(11). [CrossRef]

- Ehelepola, N. D. B., Ariyaratne, K., & Dissanayake, D. S. (2021). The interrelationship between meteorological parameters and leptospirosis incidence in Hambantota district, Sri Lanka 2008-2017 and practical implications. PLoS ONE, 16(1 January), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Ehelepola, N., Ariyarante, K., & Dissanayake, W. (2019). The correlation between local weather and leptospirosis incidence in Kandy district , Sri Lanka from 2006 to 2015. Global Health Action, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Palma, F. A. G., Costa, F., Lustosa, R., Mogaji, H. O., de Oliveira, D. S., Souza, F. N., Reis, M. G., Ko, A. I., Begon, M., & Khalil, H. (2022). Why is leptospirosis hard to avoid for the impoverished? Deconstructing leptospirosis transmission risk and the drivers of knowledge, attitudes, and practices in a disadvantaged community in Salvador, Brazil. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(12), e0000408. [CrossRef]

- Putz, E. J., Sivasankaran, S. K., Fernandes, L. G. V, Brunelle, B., Lippolis, J. D., Alt, D. P., Bayles, D. O., Hornsby, R. L., & Nally, J. E. (2021). Distinct transcriptional profiles of Leptospira borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo strains JB197 and HB203 cultured at different temperatures. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 15(4), 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Zuccarini, N. S., Lutfi, S., & Piskorowski, T. (2019). Polyneuritis and Rare Sequelae of Leptospirosis Contracted While on an Urban Clean-Up Mission in Detroit : A Case Report of Weil’s Disease and Literature Review. Journal of Medical Cases, 10(6), 183–187. [CrossRef]

- Mai, L. T. P., Dung, L. P., Mai, T. N. P., Hanh, N. T. M., Than, P. D., Tran, V. D., Quyet, N. T., Hai, H., Ngoc, D. B., Hai, P. T., Hoa, L. M., Thu, N. T., Duong, T. N., & Anh, D. D. (2022). Characteristics of human leptospirosis in three different geographical and climatic zones of Vietnam: A hospital-based study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 120, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Murillo, A., Goris, M., Ahmed, A., Cuenca, R., & Pastor, J. (2020). Leptospirosis in cats: Current literature review to guide diagnosis and management. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 22(3), 216–228. [CrossRef]

- Samekto, M., Hadisaputro, S., Adi, M. S., Suhartono, S., & Widjanarko, B. (2019). Faktor-Faktor yang berpengaruh terhadap kejadian leptospirosis (studi kasus kontrol di Kabupaten Pati). Jurnal Epidemiologi Kesehatan Komunitas, 4(1), 27.

- Azócar-aedo, L., Monti, G., & Jara, R. (2014). Leptospira spp. in domestic cats from different environments: Prevalence of antibodies and risk factors associated with the seropositivity. Animals, 4(4), 612–626. [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R. K., Mishra, S., Seidel, V., Sarangi, A. K., Pintilie, L., & Kandi, V. (2022). Re-emerging zoonotic disease Leptospirosis in Tanzania amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic: Needs attention – Correspondence. International Journal of Surgery, 108(November), 106984. [CrossRef]

- Yatbantoong, N., & Chaiyarat, R. (2019). Factors Associated with Leptospirosis in Domestic Cattle in Salakphra Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(6). [CrossRef]

- Fajriyah, S., Udiyono, A., & Saraswati, L. (2016). Environmental and risk factors of leptospirosis: A spatial analysis in Semarang City. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 755(1). [CrossRef]

- Cristaldi, M. A., Catry, T., Pottier, A., Herbreteau, V., Roux, E., Jacob, P., & Previtali, M. A. (2022). Determining the spatial distribution of environmental and socio-economic suitability for human leptospirosis in the face of limited epidemiological data. Infectious Diseases of Poverty.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).