Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

10 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

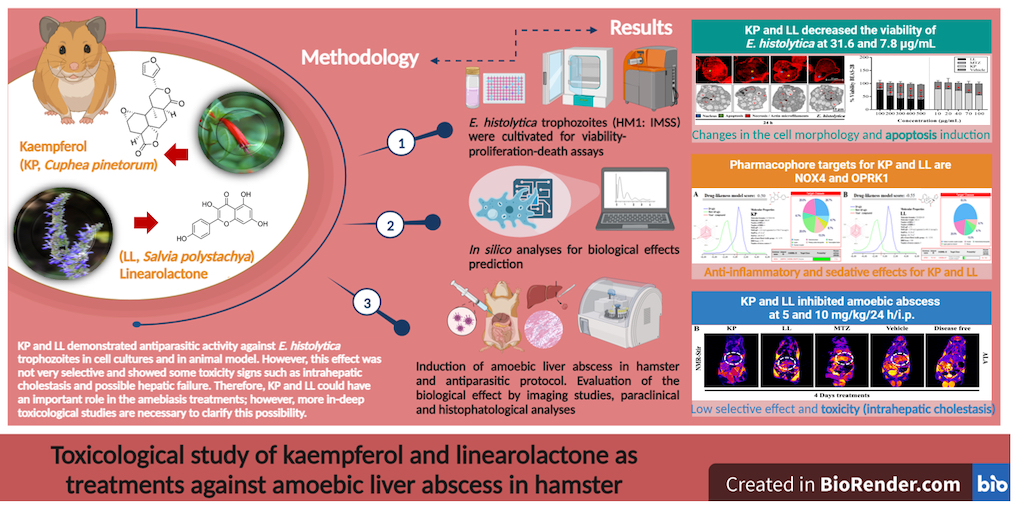

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

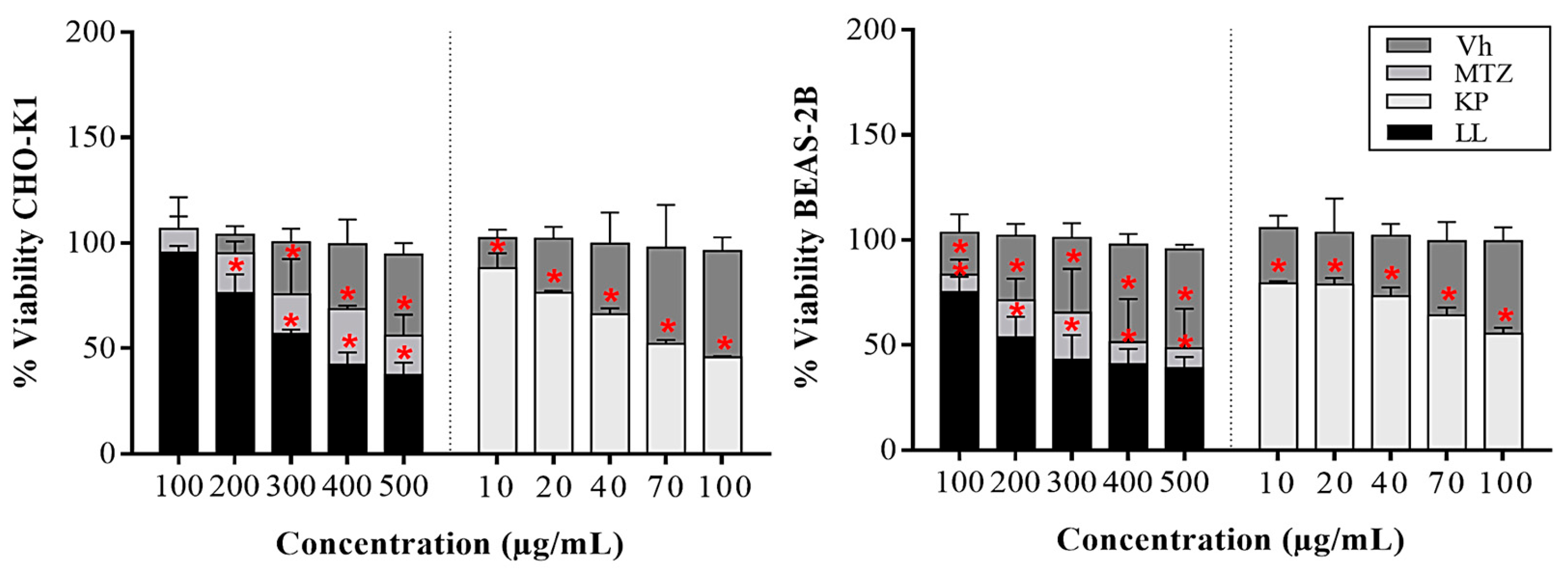

2.1. Cytotoxic Effect of the Active Principles Kp and LL in Cell Lines

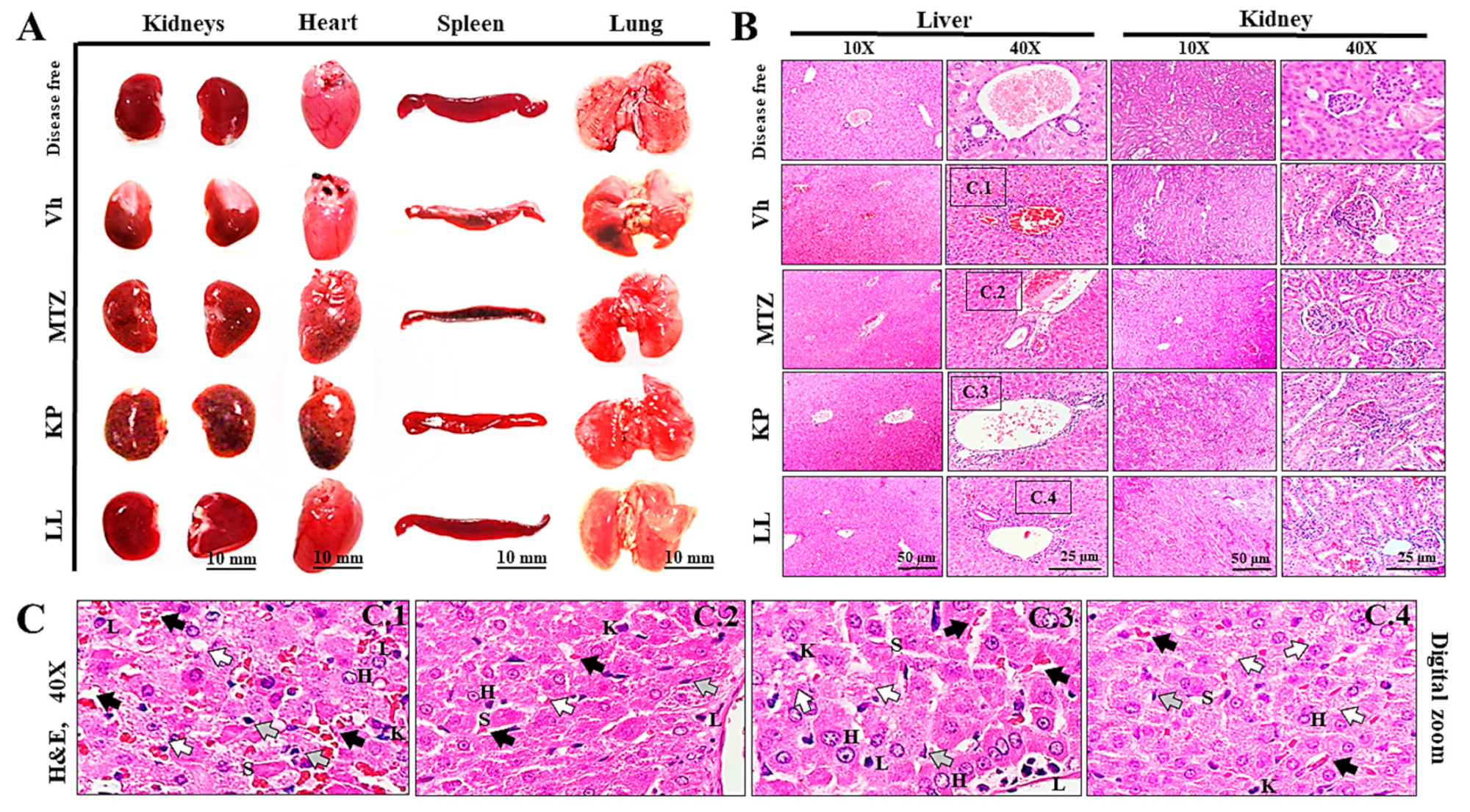

2.2. Treatment with KP or LL Selectively Induced Cell Death and Morphological Alterations in Trophozoites versus Normal Cells

2.3. Effect of Treatment with Active Principles KP and LL in ALA Model in M. auratus

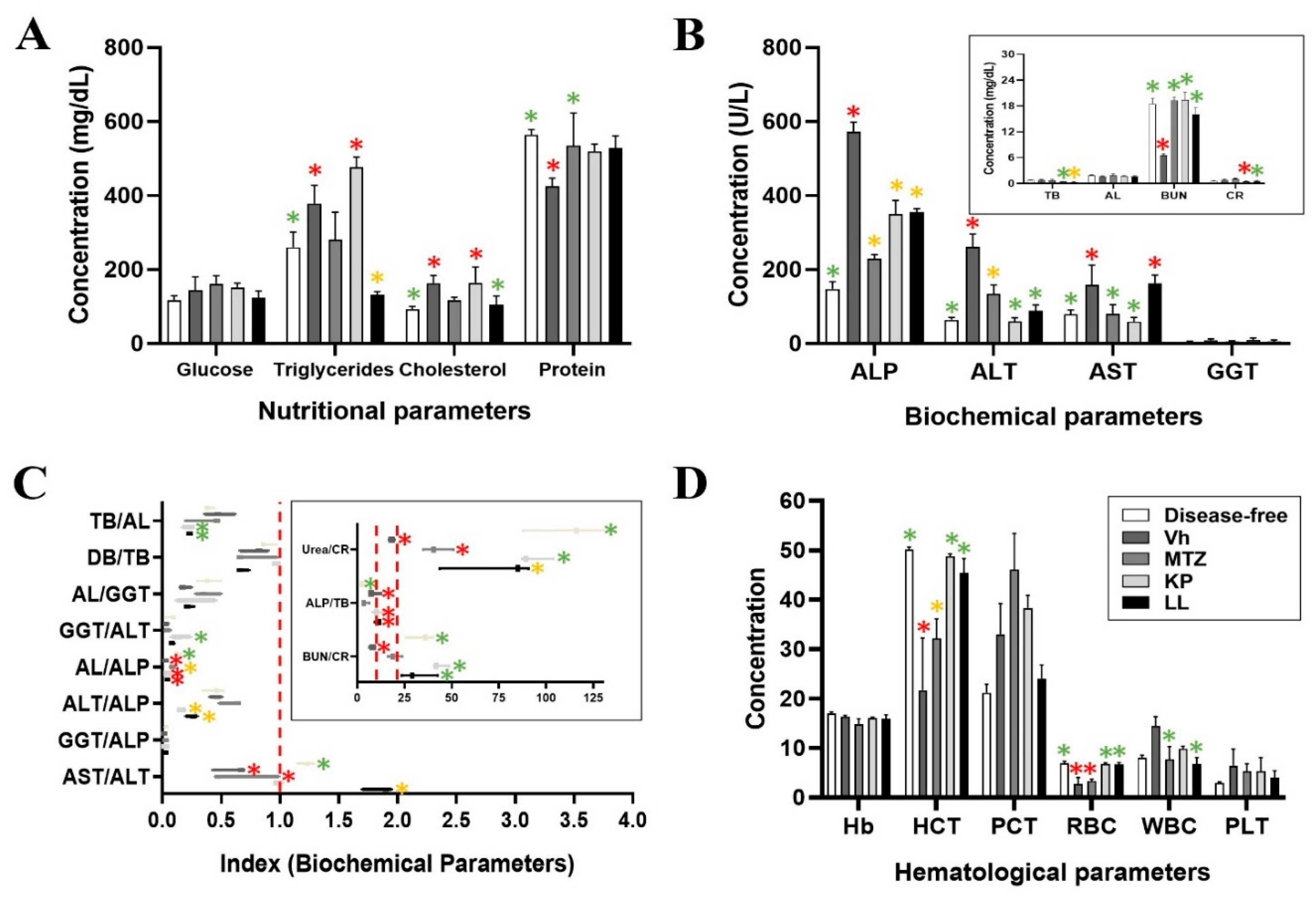

2.4. Paraclinical Analysis of Post-Treatment Liver and Kidney Function

2.5. Treatments with LL and KP Were Effective in Inhibiting the Development of ALA in M. auratus.

2.6. Toxicological Evaluation of Hamsters Treated with KP or LL during ALA Treatment

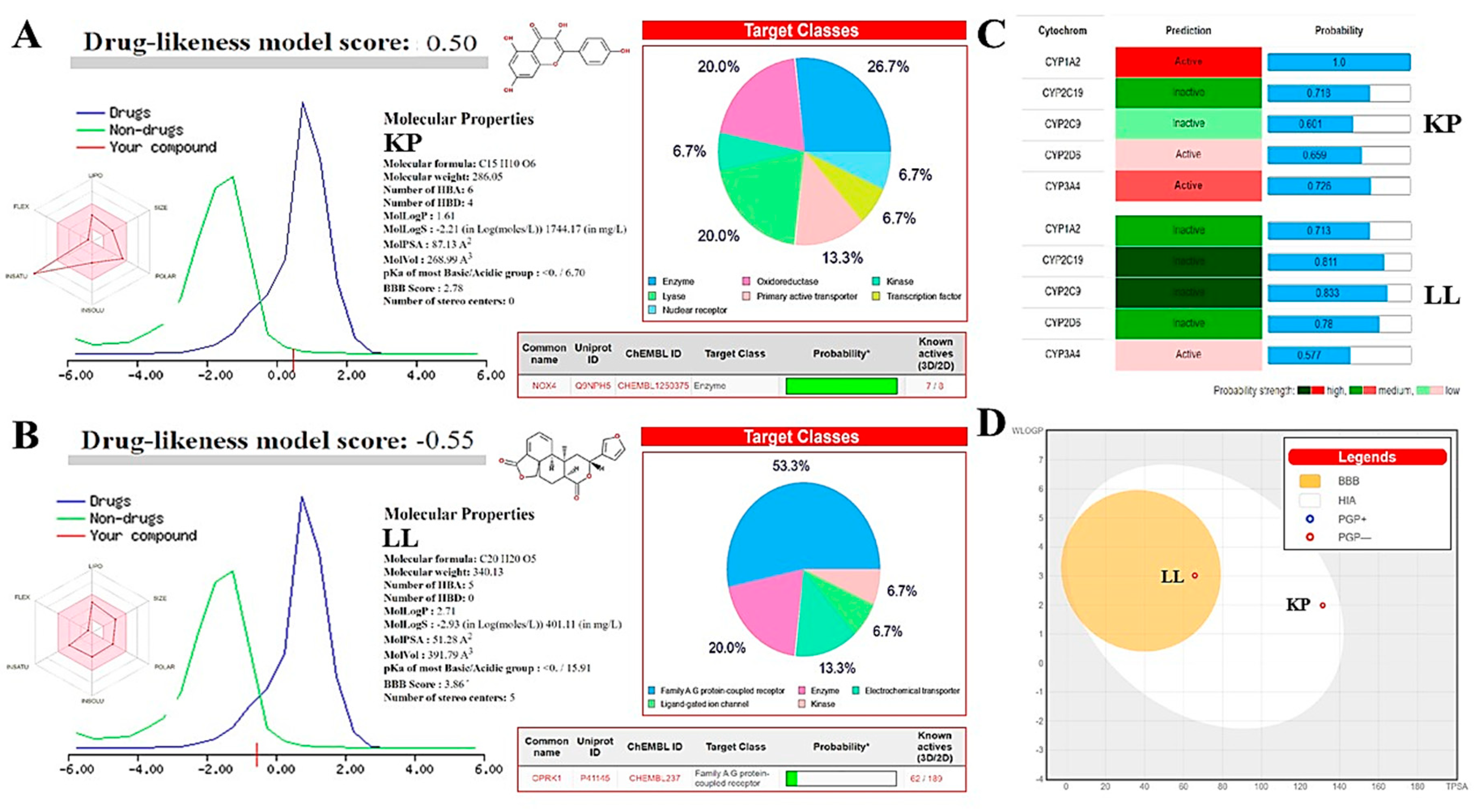

2.7. In Silico Analyses to Determine the Toxicity of KP and LL

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Isolation and Purification of Active Principles KP and LL

3.2. Cell Cultures

3.3. Cytotoxicity Assays in Normal Cell Lines by Formazan Salts

3.4. Cell Death Determination by Flow Cytometry

3.5. Cell Morphology by Confocal Microscopy

3.6. Ultrastructural Morphology Analysis via Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

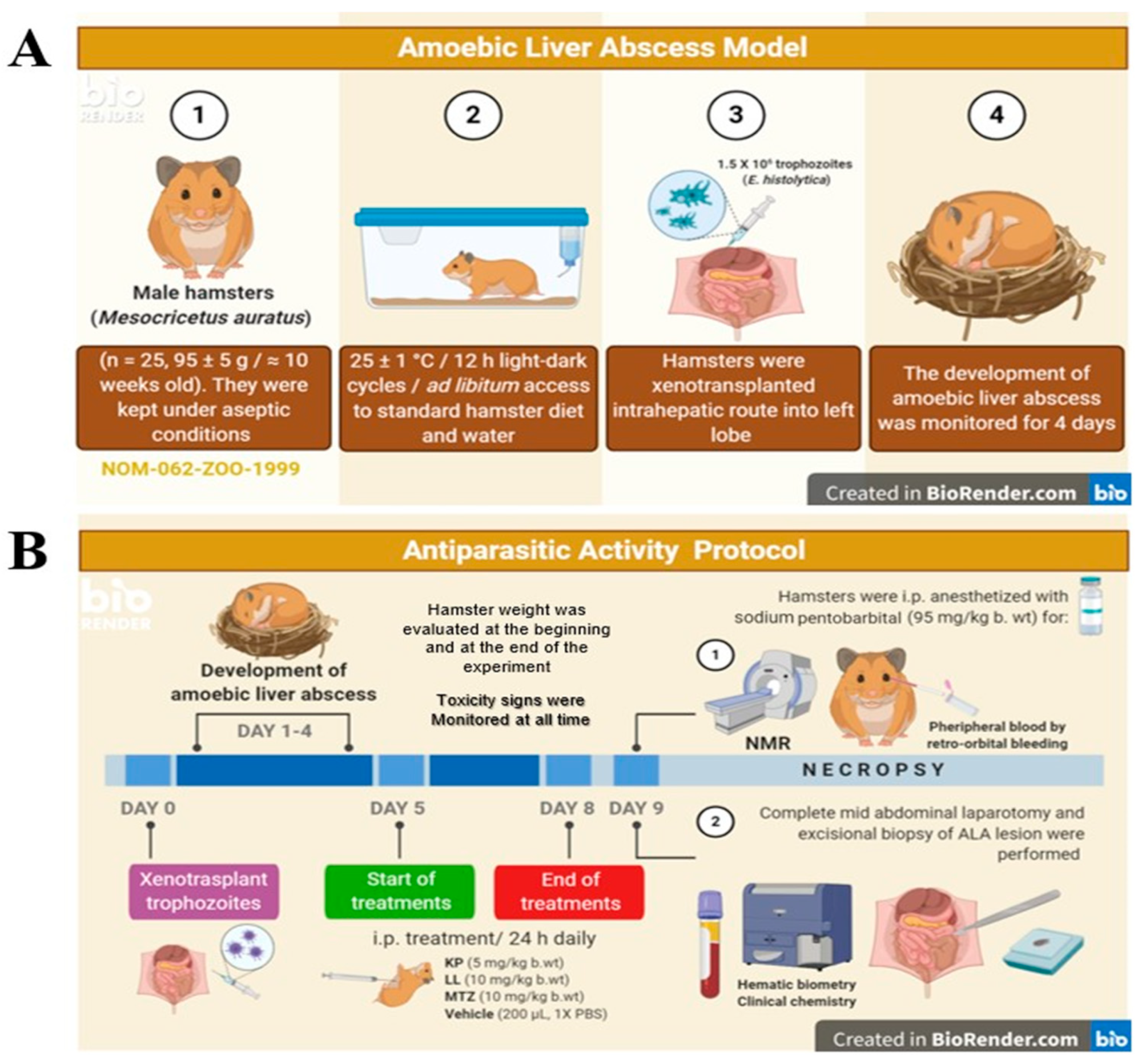

3.7. ALA Model in Hamster

3.8. Imaging Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

3.9. Paraclinical Analysis

3.10. Histopathological Analysis

3.11. In Silico Analyses

3.12. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A

References

- WHO (2017). Diarrheal disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Shirley, D.A.; Hung, C.C.; Moonah, S. (2020). Part 5, Protozoal Infections: Chapter 94 - Entamoeba histolytica (Amebiasis). In Hunter's Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10th ed.; Ryan, E.T., Hill, D.R., Solomon, T., Aronson, N.E., Endy, T.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Canada; pp. 699-706. ISBN: 978-0-323-55512-8. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, C.; Marchat, L.A.; López-Cánovas, L.; Pérez-Ishiwara, D.G.; Rodríguez, M.A.; Orozco, E. (2017). Part - Parasitic Drug Resistance, Mechanisms: Chapter - Drug Resistance Mechanisms in Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia lamblia, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Opportunistic Anaerobic Protozoa. In Antimicrobial Drug Resistance. Mechanisms of Drug Resistance; 1st ed.; Mayers, D.L., Sobel, J.D., Oullette, M., Kaye, K.S., Marchaim, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 613-628. ISBN 978-3-319-47264-5. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Martinez, M.; Hernández-Ramírez, V.I.; Hernández-Carlos, B.; Chávez–Munguía, B.; Calderón-Oropeza, M.A.; Talamás-Rohana, P. 2016. Antiamoebic activity of Adenophyllum aurantium (L.) Cystoskeleton of Entamoeba histolytica. Front Ethnopharmacol. Jun 27; 7:169.

- VADEMECUM (2017). Metronidazole. Available online: https://www.vademecum.es/principios-activos-metronidazol-J01XD01 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Tsai, J.P.; Hsieh, K.L.; Yeh, T.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Wei, C.R. (2019). The Occurrence of Metronidazole-Induced Encephalopathy in Cancer Patients: A Hospital-Based Retrospective Study. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 22(3): 344-348. [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Iqbal, W.; Adnan, F.; Wazir, S.; Khan, I.; Khayam, M.U.; Kamal, M.A.; Ahmad, S.; Ahmed, J.; Khan, I.N. (2018). Association of Metronidazole with Cancer: A Potential Risk Factor or Inconsistent Deductions?. Current Drug Metabolism, 19(11): 902-909. [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla-Licea, R.; Vargas-Villarreal, J.; Verde-Star, M.J.; Rivas-Galindo, V.M.; Torres-Hernández, Á.D. (2020). Antiprotozoal Activity against Entamoeba histolytica of Flavonoids Isolated from Lippia graveolens Kunth. Molecules, 25(11): 2464. [CrossRef]

- Llurba-Montesino, N.; Schmidt, T.J. (2018). Salvia Species as Sources of Natural Products with Antiprotozoal Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(1): 264. [CrossRef]

- Calzada, F. (2005). Additional antiprotozoal constituents from Cuphea pinetorum, a plant used in Mayan traditional medicine to treat diarrhea. Phytotherapy Research, 19(8): 725-727. [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, V.; Díaz-Martínez, A.; Soto, J.; Marchat, L.A.; Sánchez-Monroy, V.; Ramírez-Moreno, E. (2015). Kaempferol inhibits Entamoeba histolytica growth by altering cytoskeletal functions. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, 204(1): 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Domínguez, J.A.; Hernández-Ramírez, V.I.; Calzada, F.; Varela-Rodríguez, L.; Pichardo-Hernández, D.L.; Bautista, E.; Herrera-Martínez, M.; Castellanos-Mijangos, R.D.; Matus-Meza, A.S.; Chávez-Munguía, B.; Talamás-Rohana, P. (2020). Linearolactone and kaempferol disrupt the actin cytoskeleton in Entamoeba histolytica: inhibition of amoebic liver abscess development. Journal of Natural Products, 83(12): 3671-3680. [CrossRef]

- Calzada, F.; Yepez-Mulia, L.; Tapia-Contreras, A.; Bautista, E.; Maldonado, E.; Ortega, A. (2010). Evaluation of the antiprotozoal activity of neo-clerodane type diterpenes from Salvia polystachya against Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia. Phytotherapy research, 24(5): 662-665. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.S.; Harlow, D.R.; Cunnick, C.C. (1978). A new medium for the axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and other Entamoebas; Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 72(4): 431-432. [CrossRef]

- Argüello-García R, Calzada F, Chávez-Munguía B, Matus-Meza AS, Bautista E, Barbosa E, Velázquez, C., Hernández-Caballero ME, Ordoñez-Razo RM, Velázquez-Domínguez JA. Linearolactone Induces Necrotic-like Death in Giardia intestinalis trophozoites: Prediction of a Likely Target. (2022). Pharmaceuticals; 15(7):809. [CrossRef]

- Kalra, A.; Yetiskul, E.; Wehrle, C.J.; Tuma, F. (2020). Physiology, Liver. In StatPearls [Internet], 1st ed.; Abai, B., Abu-Ghosh, A., Acharya, A.B., et al., Eds.; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, Florida, United State. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535438/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Rovegno, M.; Vera, M.; Ruiz, A.; Benítez, C. (2019). Current concepts in acute liver failure. Annals of Hepatology, 18(4): 543-552. [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. (2001). Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Advanced drug delivery reviews, 46(1-3): 3-26. [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Chard, L.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. (2019). Syrian Hamster as an Animal Model for the Study on Infectious Diseases. Frontiers in immunology, 10(2329): 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación (SAGARPA) (2001). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-062-ZOO-1999: Especificaciones técnicas para la producción, cuidado y uso de los animales de laboratorio. [Gobierno de México]. Disponible en: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/203498/NOM-062-ZOO-1999_220801.pdf (Access: abril 20, 2023).

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; Garner, P.; Holgate, S.T.; Howells, D.W.; Karp, N.A.; Lazic, S.E.; Lidster, K.; MacCallum, C.J.; Macleod, M.; Pearl, E. J.; Würbel, H. (2020). The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS biology, 18(7): e3000410. [CrossRef]

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). (2020). AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2nd Edition. Schaumburg, IL: AVMA.

- Herrmann, K.; Flecknell, P. (2018). The application of humane endpoints and humane killing methods in animal research proposals: A retrospective review. Alternatives to laboratory animals: ATLA, 46(6): 317-333. [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2008). Section 4: Test no. 425, acute oral toxicity (up-and-down procedure). In: OECD Guidelines for the testing of chemicals, OECD (ed). OECD Publishing: Paris; 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Al Shoyaib, A.; Archie, S.R.; Karamyan, V.T. (2019). Intraperitoneal Route of Drug Administration: Should it Be Used in Experimental Animal Studies? Pharmaceutical research, 37(1): 12. [CrossRef]

- Secretaria de Salud (SSA) (2002). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-087-ECOL-SSA1-2002: Protección ambiental - Salud ambiental - Residuos peligrosos biológico-infecciosos -Clasificación y especificaciones de manejo [Gobierno de México]. Available from: http:// www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/087ecolssa.html (Access: Abril 20, 2023).

- Lindstrom, N.M.; Moore, D.M.; Zimmerman, K.; Smith, S.A. (2015). Hematologic assessment in pet rats, mice, hamsters, and gerbils: blood sample collection and blood cell identification. The veterinary clinics of North America. Exotic animal practice, 18(1): 21-32. [CrossRef]

- McKeon, G.P.; Nagamine, C.M.; Ruby, N.F.; Luong, R.H. (2011). Hematologic, serologic, and histologic profile of aged Siberian hamsters (Phodopus sungorus). Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science, 50(3): 308-316.

- Foreman, J.H.; (2023). Hyperlipemia and hepatic lipidosis in large animals. Available online: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/digestive-system/hepatic-disease-in-large-animals/hyperlipemia-and-hepatic-lipidosis-in-large-animals (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Flores, M.S.; Obregón-Cárdenas, A.; Tamez, E.; Rodríguez, E.; Arévalo, K.; Quintero, I.; Tijerina, R.; Bosques, F. & Galán, L. (2014). Hypocholesterolemia in patients with an amebic liver abscess. Gut and liver, 8(4): 415-420. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Daza, E.; Fernández, J.E.; Moreno-Mejía, I.; Moreno-Mejía, M. (2008). Aproximación al diagnóstico de enfermedades hepáticas por el laboratorio clínico. Medicina & Laboratorio, 14(11-12): 533-546.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Fang, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, W.; Zhao, J.; Wang, B.; Wu, Z.; Lv, Y. & Wu, R. (2021) Clinical significance of serum albumin/globulin ratio in patients with pyogenic liver abscess. Frontiers in Surgery, 8: 677799. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, E.G.; Testa, R. & Savarino, V. (2005). Liver enzyme alteration: a guide for clinicians. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal, 172(3):367-379. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhou, X. & Zhang, Z. (2022). The diagnostic value of GGT-based biochemical indicators for choledocholithiasis with negative imaging results of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Contrast media & molecular imaging, 2022(7737610): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, V.; Mena-López, R.; Anaya-Velázquez, F.; Martínez-Palomo, A. (1984). Cellular bases of experimental amebic liver abscess formation. The American journal of pathology, 117(1): 81-91.

- Priyadarshi, R.N.; Kumar, R.; Anand, U. (2022). Amebic liver abscess: Clinico-radiological findings and interventional management. World Journal of Radiology, 14(8): 272-285. [CrossRef]

- Shibayama, M.; Campos-Rodríguez, R.; Ramírez-Rosales, A.; Flores-Romo, L.; Espinosa-Cantellano, M.; Martínez-Palomo, A.; Tsutsumi, V. (1998). Entamoeba histolytica: liver, invasion and abscess production by intraperitoneal inoculation of trophozoites in hamsters, Mesocricetus auratus. Experimental parasitology, 88(1): 20-27. [CrossRef]

- Denis, M.; Chadee, K. (1988). Immunopathology of Entamoeba histolytica infections. Parasitology today (Personal ed.), 4(9): 247-252. [CrossRef]

- Krishna, M. (2014). Anatomía microscópica del hígado. Clinical liver disease, 2(Suppl 5): 109-112. [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.K.; Viswanadhan, V.N.; Wendoloski, J.J. (1999). A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. Journal of combinatorial chemistry, 1(1): 55-68. [CrossRef]

- Veber, D.F.; Johnson, S.R.; Cheng, H.Y.; Smith, B.R.; Ward, K.W.; Kopple, K.D. (2002). Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 45(12): 2615-2623. [CrossRef]

- Egan, W.J.; Merz, K.M. Jr; Baldwin, J.J. (2000). Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 43(21): 3867-3877. [CrossRef]

- Karthika, C.; Sureshkumar, R.; Zehravi, M.; Akter, R.; Ali, F.; Ramproshad, S.; Mondal, B.; Tagde, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Khan, F.S.; Rahman, M.H.; Cavalu, S. (2022). Multidrug resistance of cancer cells and the vital role of P-Glycoprotein. Life, 12(6): 897. [CrossRef]

- Rajaram, R.D.; Dissard, R.; Jaquet, V.; De Seigneux, S. (2019). Potential benefits and harms of NADPH oxidase type 4 in the kidneys and cardiovascular system. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation, 34(4): 567-576. [CrossRef]

- Dalefield, M.L.; Scouller, B.; Bibi, R.; Kivell, B.M. (2022). The Kappa Opioid Receptor: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Multiple Pathologies. Frontiers in pharmacology, 13(837671): 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.A.; (2022). Renal dysfunction in small animals. Available online: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/urinary-system/noninfectious-diseases-of-the-urinary-system-in-small-animals/renal-dysfunction-in-small-animals (accessed on 30 May 2023).

- Vicente, D. & Pérez-Trallero, E. (2010). Tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and metronidazole. Enfermedades infecciosas y microbiología clínica, 28(2): 122-130. [CrossRef]

- Lala, V.; Zubair, M.; Minter, D.A. Liver Function Tests. [Updated 2022 Oct 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482489/.

- Bansal, Y.; Maurya, V.; Tak, V.; Bohra, G.K.; Kumar, D.; Goel, A.D.; Yadav, T.; Nag, V.L. (2022). Clinical and laboratory profile of patients with amoebic liver abscess. Tropical parasitology, 12(2): 113-118. [CrossRef]

- Reyna-Sepúlveda, F.; Hernández-Guedea, M.; García-Hernández, S.; Sinsel-Ayala, J.; Muñoz-Espinoza, L.; Pérez-Rodríguez, E.; Muñoz-Maldonado, G. (2017). Epidemiology and prognostic factors of liver abscess complications in northeastern Mexico. Medicina Universitaria, 19(77): 178-183. [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. & Cash, J. (2012). What is the real function of the liver 'function' tests? The Ulster medical journal, 81(1): 30-36.

- Loaeza-del-Castillo, A.; Paz-Pineda, F.; Oviedo-Cárdenas, E.; Sánchez-Ávila, F.; Vargas-Vorácková, F. (2008). AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) for the noninvasive evaluation of liver fibrosis. Annals of Hepatology, 7(4): 350-357. [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.X.; Chen, X.Q.; He, X.L.; Lan, L.C.; Tang, Q.; Huang, L.; Shan, Q.W. (2022). Screening for Wilson's disease in acute liver failure: A new scoring system in children. Frontiers in pediatrics, 10: 1003887. [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, S.; Sawai, S.; Satoh, M.; Seimiya, M.; Sogawa, K.; Fukumura, A.; Tsutsumi, M.; Nomura, F. (2016). Fractionation of gamma-glutamyltransferase in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease. World journal of hepatology, 8(36): 1610-1616. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ni, X.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, C.; Qi, X.; Huo, H.; Lou, X.; Fan, Q.; Bao, Y.; Luo, M. (2021). Serum GGT/ALT ratio predicts vascular invasion in HBV-related HCC. Cancer cell international, 21(1): 517. [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Yin, W.T.; Sun, D.W. (2021). Albumin-to-alkaline phosphatase ratio as a promising indicator of prognosis in human cancers: is it possible? BMC cancer, 21(1): 247. [CrossRef]

- Hulzebos, C.V.; Dijk, P.H. (2014). Bilirubin-albumin binding, bilirubin/albumin ratios, and free bilirubin levels: where do we stand? Seminars in perinatology, 38(7): 412-421. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Chung, K.S.; Lee, E.H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Kang, Y.A.; Park, M.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Chang, J.; Leem, A.Y. (2020). The role of bilirubin to albumin ratio as a predictor for mortality in critically ill patients without existing liver or biliary tract disease. Acute and critical care, 35(1): 24-30. [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.S.; Mishra, S.K.; Mohanty, S.; Pattnaik, J.K.; Das, B.S. (2003). Influence of renal impairment on plasma concentrations of conjugated bilirubin in cases of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Annals of tropical medicine and parasitology, 97(6): 581-586. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez de Cossío, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, R. (2011). Pruebas de laboratorio en atención primaria (II). Medicina de Familia SEMERGEN, 37(3): 130-135. [CrossRef]

- Brookes, E.M.; Power, D.A. (2022). Elevated serum urea-to-creatinine ratio is associated with adverse inpatient clinical outcomes in non-end stage chronic kidney disease. Scientific Reports, 12(20827): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Jorge Morales, B. (2010). Drogas Nefrotóxicas. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, 21(4): 623-628. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Sharma, S.; Gadpayle, A.K.; Gupta, H.K.; Mahajan, R.K.; Sahoo, R.; Kumar, N. (2014). Clinical, laboratory, and management profile in patients of liver abscess from northern India. Journal of tropical medicine, 2014(142382): 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Marie, C.S.; Verkerke, H.P.; Paul, S.N.; Mackey, A.J.; Petri, W.A. Jr. (2012). Leptin protects host cells from Entamoeba histolytica cytotoxicity by a STAT3-dependent mechanism. Infection and immunity, 80(5): 1934-1943. [CrossRef]

- López-Contreras, L.; Hernández-Ramírez, V.I.; Herrera-Martínez, M.; Montaño, S.; Constantino-Jonapa, L.A.; Chávez-Munguía, B.; Talamás-Rohana, P. (2017). Structural and functional characterization of the divergent Entamoeba Src using Src inhibitor-1. Parasites & Vectors, 10(1): 500. [CrossRef]

- Sladek, F.M. (2011). What are nuclear receptor ligands? Molecular and cellular endocrinology, 334(1-2): 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, D.E.; Siderovski, D.P. (2013). G protein signaling in the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Experimental & molecular medicine, 45(3): e15. [CrossRef]

- Basith, S.; Cui, M.; Macalino, S.; Park, J.; Clavio, N.; Kang, S.; Choi, S. (2018). Exploring G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) ligand space via cheminformatics approaches: impact on rational drug design. Frontiers in pharmacology, 9(128): 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Valle-Solis, M.; Bolaños, J.; Orozco, E.; Huerta, M.; García-Rivera, G.; Salas-Casas, A.; Chávez-Munguía, B.; Rodríguez, M.A. (2018). A calcium/cation exchanger participates in the programmed cell death and in vitro virulence of Entamoeba histolytica. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 8(342): 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, S.; Qin, J.; Peng, M.; Qian, J.; Zhou, P. (2022). Prognostic value of platelet count-related ratios on admission in patients with pyogenic liver abscess. BMC infectious diseases, 22(1): 636. [CrossRef]

- Mosmann, T. (1983). Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Journal of immunological methods, 65(1-2): 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Varela-Rodríguez, L.; Sánchez-Ramírez, B.; Saenz-Pardo-Reyes, E.; Ordaz-Ortiz, J.J.; Castellanos-Mijangos, R.D.; Hernández-Ramírez, V.I.; Cerda-García-Rojas, C.M.; González-Horta, C.; Talamás-Rohana, P. (2021). Antineoplastic Activity of Rhus trilobata Nutt. (Anacardiaceae) against Ovarian Cancer and Identification of Active Metabolites in This Pathology. Plants, 10(10): 2074. [CrossRef]

- Varela-Rodríguez, L.; Sánchez-Ramírez, B.; Rodríguez-Reyna, I.; Ordaz-Ortiz, J.J.; Chávez-Flores, D.; Salas-Muñoz, E.; Osorio-Trujillo, J.C.; Ramos-Martínez, E.; Talamás-Rohana, P. (2019). Biological and toxicological evaluation of Rhus trilobata Nutt. (Anacardiaceae) used traditionally in Mexico against cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med 2019 Jul 1; 19(1):153.

- Calzada, F.; Meckes, M.; and Cedillo-Rivera, R. ; 1999. Antiamebic and antigiardial activity of plant flavonoids; Planta Med. 65:78-80.

- Chávez-Munguía, B.; Salazar-Villatoro, L.; Omaña-Molina, M.; Espinosa-Cantellano, M.; Ramírez-Flores, E.; Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Martínez-Palomo, A. (2016). Acanthamoeba culbertsoni: Electron-Dense Granules in a Highly Virulent Clinical Isolate. The Journal of eukaryotic microbiology, 63(6): 744-750. [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Ruiz, D.M.; Aguilar-Díaz, H.; Bobes, R.J.; Sampieri, A.; Vaca, L.; Laclette, J.P.; Carrero, J.C. (2015). Protection against Amoebic Liver Abscess in Hamster by Intramuscular Immunization with an Autographa californica Baculovirus Driving the Expression of the Gal-Lectin LC3 Fragment. BioMed research international, 2015(760598): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Martínez, M.; Hernández-Ramírez, V.I.; Hernández-Carlos, B.; Chávez-Munguía, B.; Calderón-Oropeza, M.A.; Talamás-Rohana, P. (2016). Antiamoebic Activity of Adenophyllum aurantium (L.) Strother and Its Effect on the Actin Cytoskeleton of Entamoeba histolytica. Frontiers in pharmacology, 7(169): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. (2017). SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Scientific reports, 7(42717): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. (2019). SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic acids research, 47(1): 357-364. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Srivastava, G.N.; Roy, A.; Sharma, V.K. (2017) ToxiM: A Toxicity Prediction Tool for Small Molecules Developed Using Machine Learning and Chemoinformatics Approaches. Frontier in Pharmacology, 8(880): 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Martin, T.; Harten, P.; Young, D. (2012). TEST (Toxicity Estimation Software Tool) Ver 4.1. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, EPA/600/C-12/006.

- Banerjee, P.; Dunkel, M.; Kemmler, E.; Preissner, R. (2020). SuperCYPsPred-a web server for the prediction of cytochrome activity. Nucleic acids research, 48(W1): W580-W585. [CrossRef]

- Maunz, A.; Gütlein, M.; Rautenberg, M.; Vorgrimmler, D.; Gebele, D.; Helma, C. (2013). lazar: a modular predictive toxicology framework. Frontiers in pharmacology, 4(38): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Muegge, I.; Heald, S.L.; Brittelli, D. (2001). Simple selection criteria for drug-like chemical matter. Journal of medicinal chemistry, 44(12): 1841-1846. [CrossRef]

- Nigam, P.; Gupta, A.K.; Kapoor, K.K.; Sharan, G.R.; Goyal, B.M.; Joshi, L.D. (1985). Cholestasis in amoebic liver abscess. Gut, 26(2): 140-145. [CrossRef]

- Chalasani, N.; Younossi, Z.; Lavine, J.E.; Charlton, M.; Cusi, K.; Rinella, M.; Harrison, S.A.; Brunt, E.M.; Sanyal, A.J. (2018). The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), 67(1): 328-357. [CrossRef]

- Konigsfeld, H.P.; Viana, T.G.; Pereira, S.C.; Santos, T.O.C.D.; Kirsztajn, G.M.; Tavares, A.; De Souza Durão Junior, M. (2019). Acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients who underwent percutaneous kidney biopsy for histological diagnosis of their renal disease. BMC nephrology, 20(1): 315. [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.Z.; Zhang, S.Y.; Zhou, H.L. (2016). Toxicological evaluation of the flavonoid-rich extract from Maydis stigma: Sub-chronic toxicity and genotoxicity studies in mice. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 192: 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Kebede, S.; Afework, M.; Debella, A.; Ergete, W.; Makonnen, E. (2016). Toxicological study of the butanol fractionated root extract of Asparagus africanus Lam., on some blood parameter and histopathology of liver and kidney in mice. BMC research notes, 9: 49. [CrossRef]

- Agus, H.H. Chapter 4 - Terpene toxicity and oxidative stress. In Toxicology: Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants, 1st ed.; Patel, A.V., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press: London, United Kingdom, 2021; Volume 1:33-42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| In vitro studies: IC50, SI and LD50 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | Vh | MTZ | KP | LL |

| IC50 HM-1 | Innocuous | 0.16 ++ * | 31.6 + * | < 7.8 + * |

| IC50 CHO-K1 | Innocuous | 500 - * | 70 +/- * | 300 - * |

| IC50 BEAS-2B | Innocuous | 400 - * | 100 +/- * | 200 - * |

| SI | ND | 3,461 ++ | 2.7 +/- | > 32 + |

| LD50 (Theoretical) | ND | 1,025.64 | 551.75 | 824.20 |

| In vivo studies: acute toxicity and ALA characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Vh | MTZ | KP | LL |

| Hamster weight (g) | 91.9 ± 2.3 | 95.4 ± 5.1 | 93.5 ± 6 | 93.4 ± 7.2 |

| Toxicity signs | None | None | None | None |

| Survivors (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| ALA Weight (g) | 1.23 ± 0.15 | 0.33 ± 0.32 * | 0.86 ± 0.15 * | 0.40 ± 0.20 * |

| ALA Volume (mm3) | 2.257 ± 523.7 | 528 ± 183.5 * | 738 ± 150 * | 562.3 ± 23.3 * |

| NMR (T1/ T2) | Intermediate intensity/ Hyperintense |

Intermediate intensity/ Hypointense | Intermediate intensity/ Hypointense |

Intermediate intensity/ Hypointense |

| Leukocyte infiltrate | ++ | - | +/- | +/- |

| Fibrosis | + | -- | -- | -- |

| Liquid | ++ | - | +/- | - |

| Edges | Irregular and poorly defined | Regular and well defined | Irregular and poorly defined | Regular and well defined |

| Morphology | Loculated ovoid | Round | Ovoid | Loculated ovoid |

| Treatments (%) | Disease-free | Vh | MTZ | KP | LL | Reference range (mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytes | 42 ± 4 | 35 ± 13 | 50 ± 13 | 39 ± 12 | 44 ± 21 | 40-85 (63) |

| Monocytes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1-6 (3) |

| Eosinophils | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1-2 |

| Basophils | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0-5 (2) |

| Segmented neutrophils | 54 ± 2 | 64 ± 14 | 51 ± 13 | 60 ± 11 | 56 ± 21 | 25-55 (40) |

| Band neutrophils | 4 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 0 | 2 ± 1 | 0 | 5-13 (9) |

| Immature forms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Organs | Disease-free | Vh | MTZ | KP | LL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 6.7 ± 0.07/4.04 ± 0.05 | 8.28 ± 1.1*/4.7 ± 0.5* | 5.76 ± 1.4/4 ± 0.15 | 5.9 ± 0.8/3.88 ± 0.11 | 5.5 ± 0.9/3.94 ± 0.16 |

| Heart | 0.4 ± 0.0/0.8 ± 0.09 | 0.38 ± 0.05/1.06 ± 0.09 | 0.38 ± 0.1/1.08 ± 0.04 | 0.38 ± 0.1/1.06 ± 0.08 | 0.38 ± 0.08/1.1 ± 0.07 |

| Kidneys | 0.65 ± 0.07/1.2 ± 0.14 | 0.62 ± 0.03/1.2 ± 0.07 | 0.52 ± 0.0/1.3 ± 0.08 | 0.49 ± 0.04/1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.49 ± 0.07/1.1 ± 0.08 |

| Lungs | 0.67 ± 0.0/2.8 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.05/2.6 ± 0.2 | 0.68 ± 0.05/2.5 ± 0.2 | 0.74 ± 0.06/2.5 ± 0.05 | 0.74 ± 0.06/2.4 ± 0.1 |

| Spleen | 0.2 ± 0.0/3.4 ± 0.38 | 0.2 ± 0.0/3.30 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.05/3.3 ± 0.3 | 0.36 ± 0.05/3.7 ± 0.1 | 0.26 ± 0.05/3.4 ± 0.4 |

| Samples | MTZ | KP | LL |

|---|---|---|---|

| SwissADME©: Physicochemical Properties | |||

| Density: | 1.5±0.1 g/cm3 | 1.7±0.1 g/cm3 | 1.3±0.1 g/cm3 |

| Refraction index: | 1.612 | 1.785 | 1.612 |

| Polarizability: | 16.2 ± 0.5 10-24cm3 | 28.3 ± 0.5 10-24cm3 | 35.0 ± 0.5 10-24cm3 |

| Surface tension: | 60.5 ± 7.0 dyne/cm | 98.9 ± 3.0 dyne/cm | 54.6 ± 5.0 dyne/cm |

| No. heavy atoms: | 12 | 21 | 25 |

| No. of bonds: | 12 | 23 | 29 |

| No. of rings: | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| No. aromatic heavy atoms: | 5 | 16 | 5 |

| Fraction Csp3: | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| No. rotatable bonds: | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Total charge: | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Molar refractivity: | 43.25 Å | 76.01 Å | 88.42 Å |

| SwissADME©: Pharmacokinetics/Molinspiration©: Bioactivity score | |||

| GI absorption: | High | High | High |

| P-gp substrate: | No | No | No |

| Log Kp: | -7.36 cm/s | -6.70 cm/s | -6.37 cm/s |

| GPCR ligand: | - 1.09 | - 0.10 | 0.65 |

| Ion channel modulator: | - 0.87 | - 0.21 | 0.16 |

| Kinase inhibitor: | - 0.59 | 0.21 | - 0.13 |

| Nuclear receptor ligand: | - 1.74 | 0.32 | 0.66 |

| Protease inhibitor: | - 1.68 | - 0.27 | 0.04 |

| Enzyme inhibitor: | - 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.47 |

| SwissADME©: Medicinal Chemistry | |||

| PAINS: | 0 alert | 1 alert (catechol A) | 0 alert |

| Brenk: | 2 alerts (Nitro group) | 1 alert (catechol A) | 1 alert (> 2 esters) |

| Leadlikeness: | No (M.W. < 250) | Yes | Yes |

| Synthetic accessibility: | 2.30 | 3.14 | 5.56 |

| T.E.S.T.© and LAZAR©: Toxicological properties | |||

| LD50 Fathead minnow (96 h): | 424.1 mg/L | 1.28 mg/L | ND |

| LD50 Daphnia magna (48 h): | 39.14 mg/L | 3.62 mg/L | ND |

| IGC50 T. pyriformis (48 h): | 270.22 | 10.54 mg/L | ND |

| LD50 Rat (Oral): | 2,444 | 2,018 mg/kg | ND |

| Bioconcentration factor: | 1.914 | 8.032 | ND |

| Developmental toxicity: | Not | Yes | ND |

| AMES mutagenicity: | Yes (p = 0.67) | Yes (p = 0.42) | ND |

| Carcinogenicity (rodents): | ND | No (p = 0.43) | ND |

| Adverse effects (rat) | ND | 1,320 mg/kg/day | ND |

| Estrogen Receptor RBA: | 5.089 10-4 | 0.004 | ND |

| Estrogen Receptor Binding: | Yes | Yes | ND |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).