1. Introduction

Eye refraction can be influenced by the accommodative status of the patient, especially in children and patients with high accommodative tonus [

1]. To accurately determine the refractive error of the eye, it is necessary to relax the patient’s accommodation either by optical methods, such as the fogging technique, or by pharmacological methods, such as cycloplegia. In Latvia, optical fogging is the standard procedure used by optometrists, whereas cycloplegia is typically performed by ophthalmologists. It has been demonstrated that fogging techniques reveal significantly lower plus values than refraction with cycloplegia [

2], leading to biased classification of refractive errors [

3,

4]. Several authors emphasize that cycloplegic refraction is essential for preventing misclassification of refractive errors in children [

3,

4,

5]. Globally, cycloplegic refraction is accepted as a standard procedure for assessing refractive errors in paediatric eye examinations and is the gold standard for epidemiological studies [

6,

7]. Clinical studies have highlighted the importance of cycloplegia for correct refractive error estimation to reveal latent hyperopia and to avoid overestimation of myopia [

8,

9]. Careful selection of a cycloplegic procedure regimen (including agent, dose, and interval) should be tailored according to ethnic origin because the absorption of cycloplegic agents decreases in individuals with darker irises [

10,

11]. Hence, achieving sufficient cycloplegia may be more challenging, necessitating higher concentrations of cycloplegic agents or more drops [

12]. The majority of previous studies evaluating changes in eye refraction after cycloplegia have been conducted in Asia [

3,

4,

5,

13,

14]. It has been noted that individuals with lighter irises achieve deeper cycloplegia with lower dosages [

15]; therefore, caution should be exercised to avoid unnecessarily high dosages of cycloplegics in the European population with light irises.

This study aims to analyze the objective refraction status before and after cycloplegia across a diverse age range, from childhood to young adulthood, in the Latvian population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

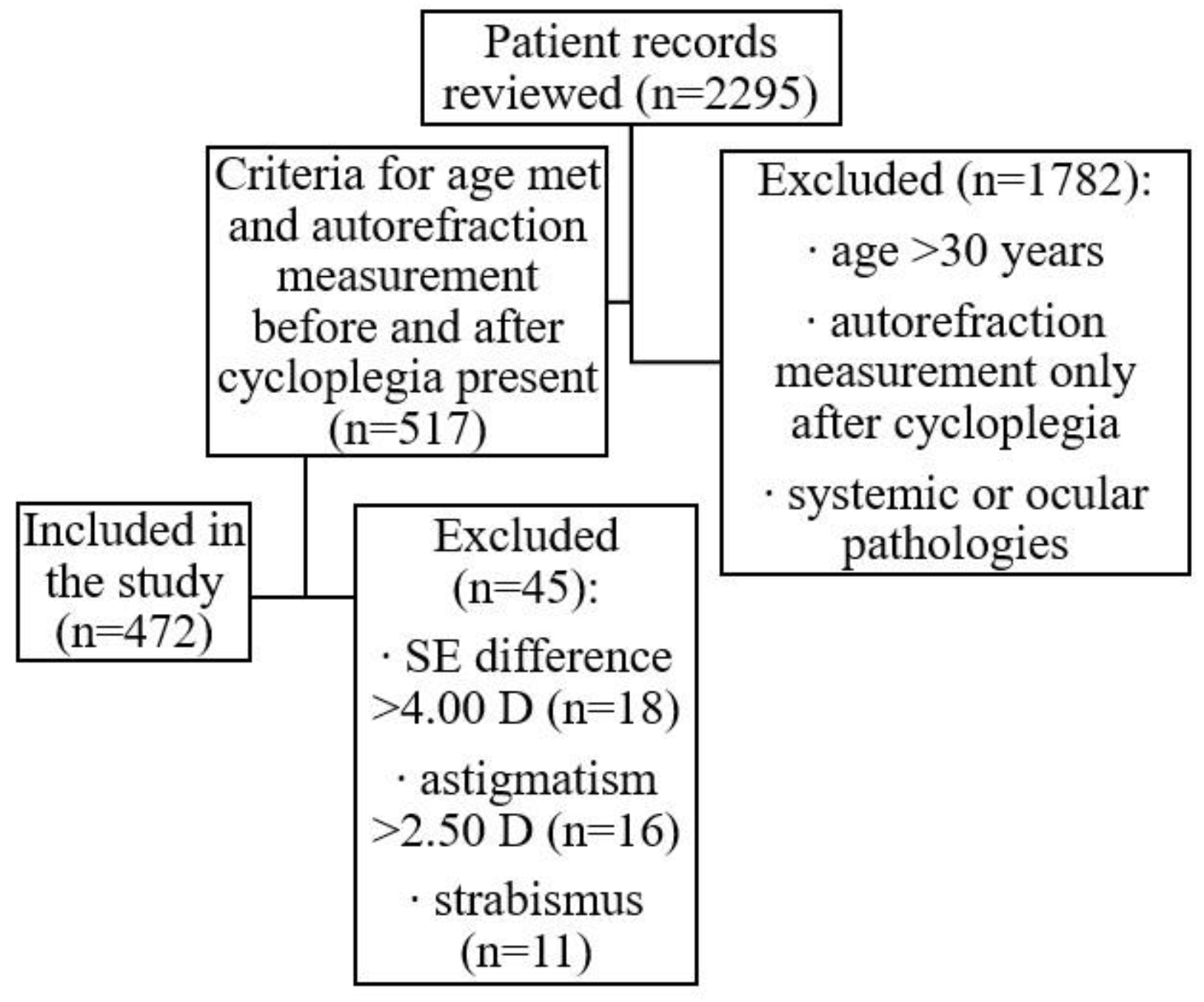

In total, 2295 patient records from a private ophthalmologist’s practice in Latvia were reviewed. From this dataset, 517 eye examinations performed with cycloplegia were selected, focusing on patients aged below 30 years. Patients with strabismus, astigmatism >2.50 D before or after cycloplegia, or a spherical equivalent (SE) change after cycloplegia >4.00 D were excluded from the sample. A total of 472 non-population-based patient records were selected for this study (see

Figure 1), representing healthy participants aged between 3 and 28 years (mean age 9.1 ± 4.6 years) who attended a private ophthalmology practice either for state-funded regular eye examinations (at ages 3 years and 6 to 7 years) or for other unspecified reasons. Of the 472 participants, 260 (55%) were female and 212 (45%) were male. For data analysis, six age groups were formed: 3–5 years (n=105, 22%); 6–8 years (n=152, 32%); 9–11 years (n=80, 17%); 12–14 years (n=71, 15%); 15–17 years (n=41, 9%); and ≥18 years (n=23, 5%).

Cycloplegia was induced by administering one drop of cyclopentolate 1% to each eye, and autorefractor measurements were performed 30 ± 5 min after the instillation of 1% cyclopentolate. For this study, only age and autorefraction measurements before and after cycloplegia were used from patient records of patients who attended private ophthalmology practice from January 2018 to December 2020. No identifiable data were included and the study conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Data Analysis

The spherical equivalent (SE) was calculated using the spherical power (Sph) and cylindrical power (Cyl) obtained from objective autorefraction measurements (SE = Sph + ½Cyl). To estimate the prevalence of refractive errors before and after cycloplegia, participants were categorized into groups based on SE values obtained from autorefractometer: emmetropia (SE from -0.25 to +0.50 D), hyperopia (SE ≥ +0.75 D), myopia (SE ≤ -0.50 D), and astigmatism (any SE indicating simple hyperopic, simple myopic astigmatism, or mixed astigmatism). Participants with compound hyperopic or myopic astigmatism, based on SE calculations, were included in the hyperopia and myopia groups, respectively. For objective refraction values with a cylindrical power of 0.25 D only spherical power was analyzed, values with a cylindrical power of 0.50 D were directly converted to SE, and values with a cylindrical power of ≥0.75 D were classified as astigmatism and allocated to either the myopia or hyperopia group (in cases of compound astigmatism) or to the astigmatism group. In the astigmatism group, the astigmatism axis was categorized as with-the-rule (negative cylinder axis 180° ± 30°), against-the-rule (negative cylinder axis 90° ± 30°), or oblique (negative cylinder axis between 31° and 59°, or 121° and 149°).

Since the SE values in the right and left eyes were highly correlated (non-cycloplegic rs = 0.86, p < 0.001 and cycloplegic rs = 0.94, p < 0.001), we analyzed the data for the left eye only (in the non-cycloplegic condition SE in the right eye was 0.14 D more myopic than in the left eye (always right eye measured first), and this difference decreased by half after cycloplegia, suggesting that for the left eye, the autorefractometer fogging managed to control accommodation better).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 22.0; IBM Corporation, USA), visualizations were made in Microsoft Excel (365). The spherical equivalent (SE) of autorefraction values under non-cycloplegic and cycloplegic conditions exhibited non-normal distributions (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, p < 0.05). Therefore, non-parametric tests were employed for analysis: the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test for comparing dependent data (specifically between non-cycloplegic and cycloplegic conditions), the Kruskal-Wallis H-test, and the Mann-Whitney U-test for comparing independent data (stratified by age, non-cycloplegic refractive status, and gender). Spearman’s rank coefficient was used to assess correlations. A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Refractive Errors before and after Cycloplegia

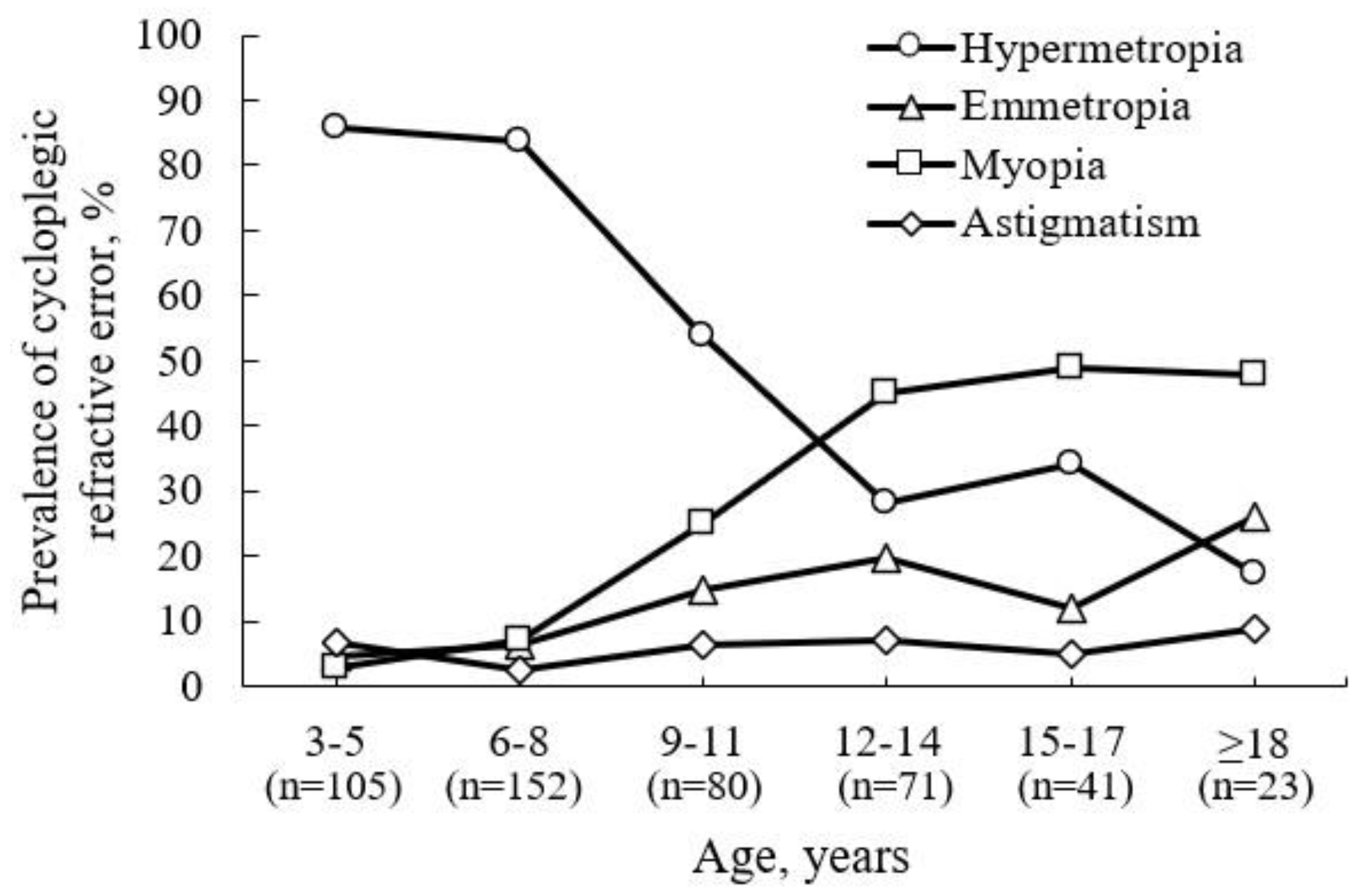

After cycloplegia, the overall prevalence of participants with hyperopia increased by 34.1%, the prevalence of myopia decreased by 5.5%, and the prevalence of emmetropia decreased by 23.3%. This reveals that the predominant refractive error for children attending ophthalmology practice (see

Figure 2) aged 3–5 and 6–8 years is hyperopia (85.7% and 83.6%, respectively), which gradually decreases with age. The prevalence of hyperopia was 53.8%, 28.2%, and 34.1% at ages 9–11, 12–14, and 15–17 years, respectively. From ages 12 to 14 years (45.1%), the predominant refractive error becomes myopia, maintaining its distribution in older age groups. The prevalence of myopia was 48.8% and 47.8% at ages 15–17 and ≥ 18 years, respectively.

A relationship was found between age and the percentage of participants for whom the refractive error type changed after cycloplegia (r

s = 0.73, p = 0.002), highlighting the clinical value of cycloplegia, especially in younger children. A change in refractive error type after cycloplegia was observed in half of the participants aged 3–5 years (51.4%) and 5–8 years (49.3%), about one-third of participants aged 9–17 years (33.8% for 9–11 years, 29.6% for 12–14 years, and 26.8% for 15–17 years), and one-fifth of participants aged 18 years or older (21.7%) (see

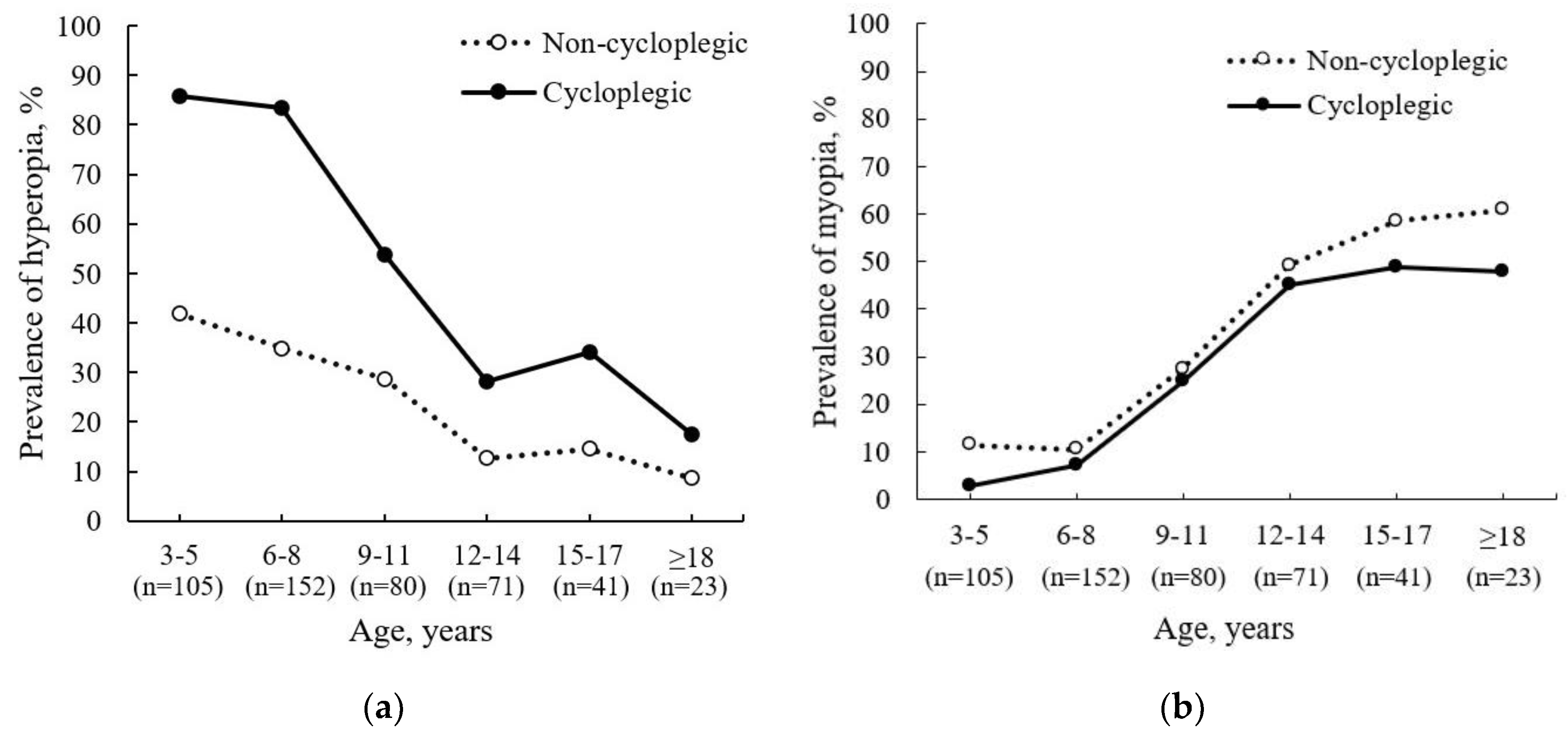

Figure 3a,b).

Our results demonstrate that non-cycloplegic autorefraction results underestimate the prevalence of hyperopia, especially in younger participants (see

Figure 3a), and overestimate the prevalence of myopia in older participants (see

Figure 3b).

3.2. Spherical Equivalent (SE) Difference after Cycloplegia

Non-cycloplegic SE (mean ± SD) was -0.01 ± 1.74 D (95% CI: -0.17 to 0.15 D), which was significantly more myopic (p < 0.001) compared to the mean cycloplegic SE of 0.71 ± 2.03 D (95% CI: 0.52 to 0.89 D). See

Table 1 for a detailed stratification by age. The average SE difference (mean ± SD) induced by cycloplegia was 0.72 ± 0.73 D (95% CI: 0.65 to 0.78 D). Cycloplegia caused a hyperopic refractive shift in SE in 83% of participants, no shift in 12%, and a myopic refractive shift in 6%. The difference in SE between non-cycloplegic and cycloplegic refraction was significantly associated with younger age (r

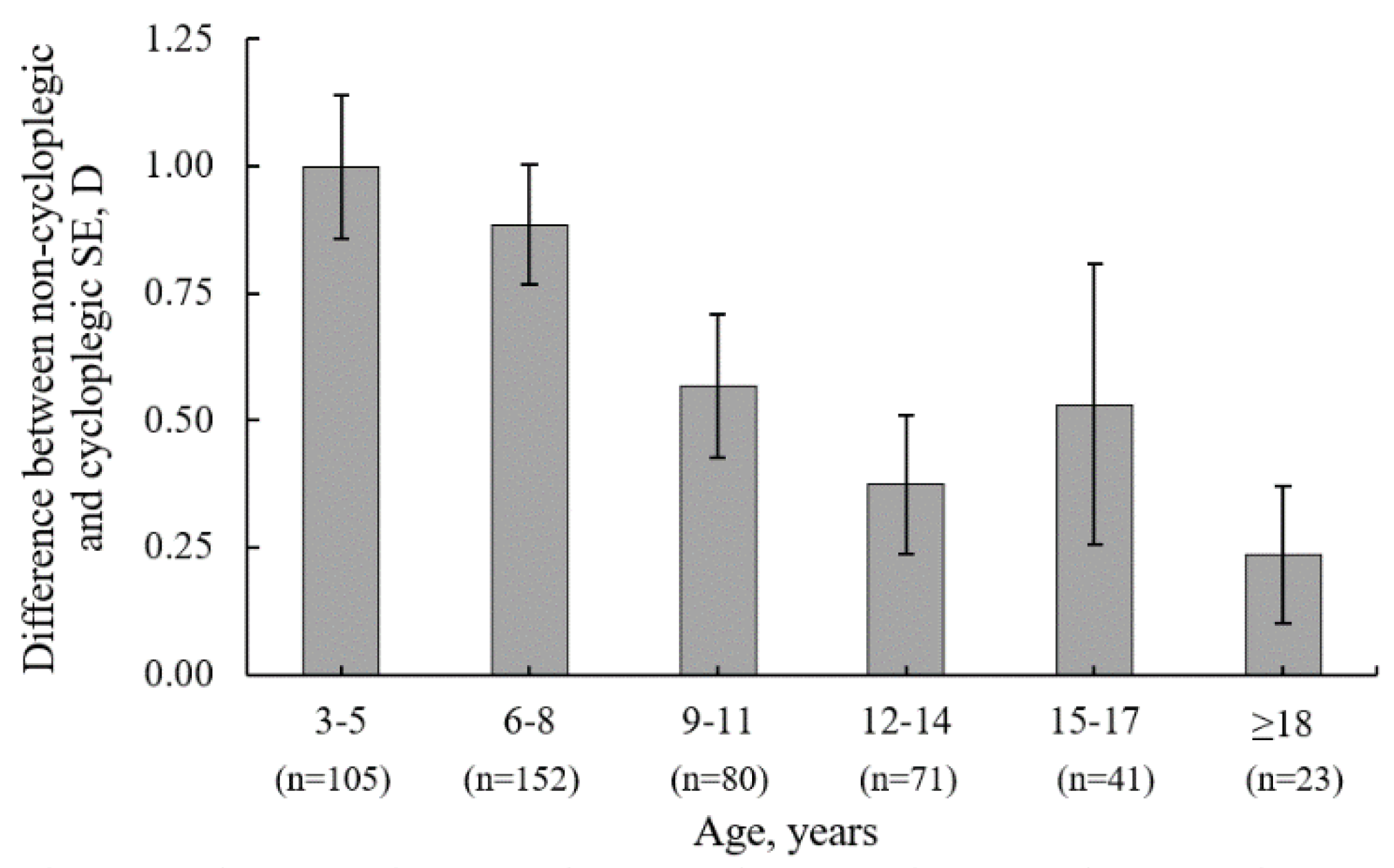

s = -0.36; p < 0.001), indicating that cycloplegia is a valuable diagnostic technique for younger children to reveal latent refractive errors that can be masked by active accommodation in non-cycloplegic autorefraction. For children aged 3 to 5 years and 6 to 8 years, the SE change after cycloplegia was higher (mean ± SE: 1.00 ± 0.73 D and 0.88 ± 0.74 D, respectively) compared to children from older groups (see

Figure 4).

When SE difference is stratified by non-cycloplegic refractive error status, the mean SE difference after cycloplegia was significantly higher for participants with hyperopia (1.03 ± 0.71 D, 95% CI: 0.95 to 1.11 D, p < 0.001) compared to participants with myopia (0.13 ± 0.37 D, 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.21 D), emmetropia (0.32 ± 0.43 D, 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.44 D), or astigmatism (0.13 ± 0.44 D, 95% CI: 0.05 to 0.31 D). The SE difference after cycloplegia was not related to gender (mean ± SD: 0.69 ± 0.73 D for females and 0.75 ± 0.74 D for males, p = 0.51).

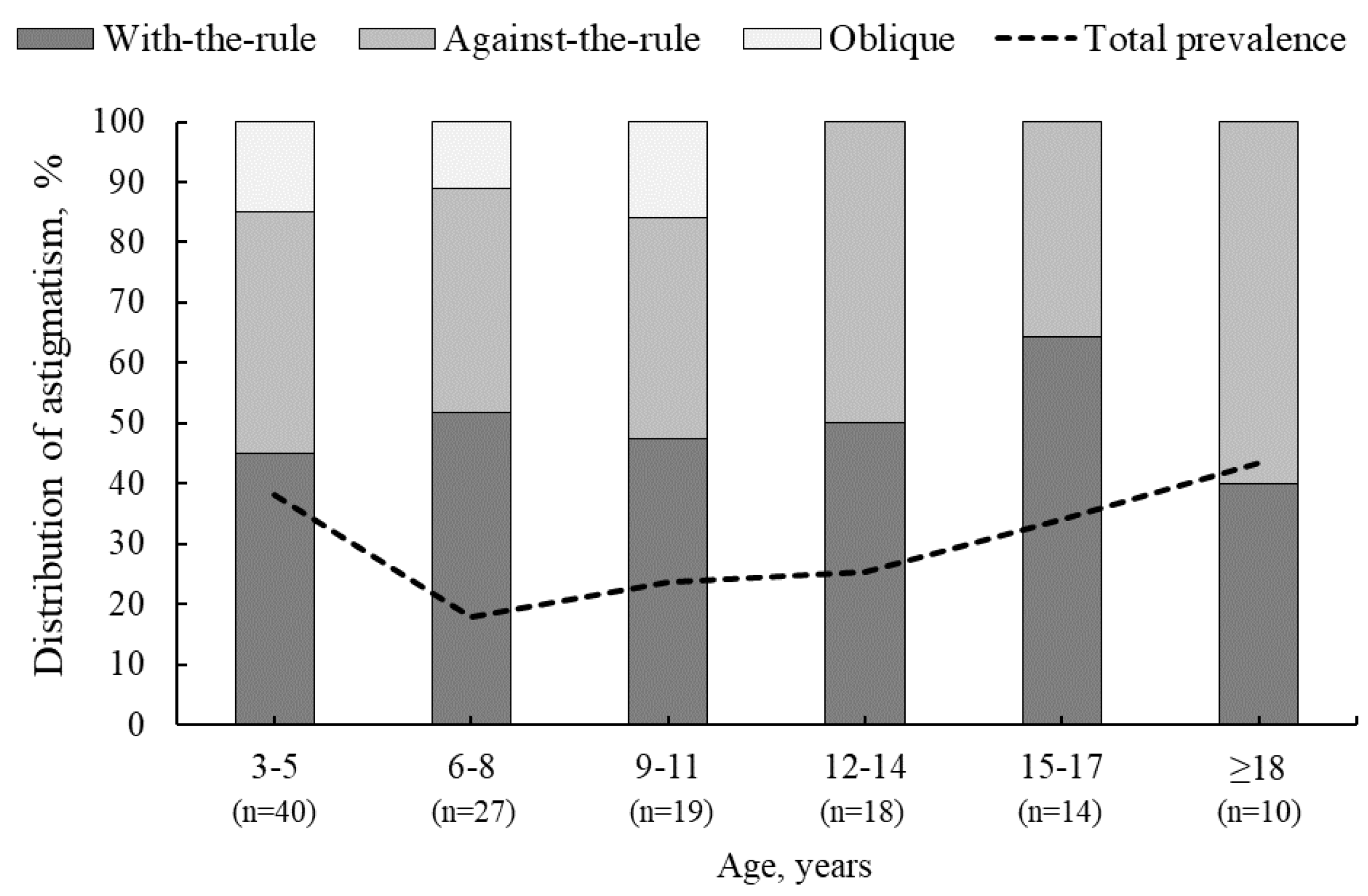

3.3. Changes in Astigmatism Power and Axis after Cycloplegia

Of the 472 participants, 36% (n=172) exhibited astigmatism ≥0.75 D before and/or after cycloplegia. The total prevalence of astigmatism was higher for participants aged 3–5 years and ≥18 years (40% and 43%, respectively), while the lowest rate of astigmatism was observed for participants aged 6–8 years (18%) (see

Figure 5). Although the difference in astigmatism between non-cycloplegic and cycloplegic conditions was not statistically significant (p = 0.84), astigmatism of ≥0.75 D was present in 134 participants (28%) before cycloplegia. After cycloplegia, astigmatism disappeared or decreased to less than 0.75 D in 9% of participants, while new astigmatism appeared in 8% of participants. Of the 44 participants who experienced a decrease in astigmatism after cycloplegia, 33 had non-cycloplegic astigmatism of 0.75 D, for 8 participants it was 1.00 D and for 3 participants it was 1.25 D. After cycloplegia, 38 participants developed cycloplegia-induced astigmatism, which did not exceed 1.25 D. Clinically significant astigmatism was present in both non-cycloplegic and cycloplegic conditions for 90 participants. For 46 participants, the amount of astigmatism remained the same before and after cycloplegia. For the remaining 44 participants, cycloplegia caused insignificant changes in the negative astigmatism axis: 13°± 17° counterclockwise in 24 participants and 12°± 18° clockwise in 20 participants (p = 0.97).

4. Discussion

In the current study, the prevalence of hyperopia after cycloplegia increased by approximately one-third (34.1%), the prevalence of myopia decreased minimally (5.5%), and the prevalence of emmetropia decreased by approximately one-fifth (23.3%). In a study by Zhao et al. (2004), the incidence of hyperopia increased by only 12.7%, whereas myopia decreased by more than half (55.9%) after cycloplegia [

3]. Sanfilippo et al. (2014) concluded that after the age of 20 years, the difference between non-cycloplegic and cycloplegic refraction is insignificant, suggesting that the cycloplegia procedure should be performed for children and young adults below 20 years of age [

14].

The results of our study are consistent with previous studies concluding that the cycloplegia procedure is a valuable diagnostic tool for accurately estimating full eye refractive status, thereby avoiding the overestimation of myopia and the underestimation of hyperopia. Our study demonstrated that for younger children aged 3–8 years, changes in SE after cycloplegia were significantly larger (p < 0.05) than those in participants aged 9–18 years. A similar trend, emphasizing the need for cycloplegia procedures in preschool children, has been demonstrated in studies performed in Asia [

4,

9,

13]. The current study also showed that the non-cycloplegic refractive error status can indicate the expected changes in SE after cycloplegia. For participants with non-cycloplegic hyperopia, the mean SE was significantly higher compared to participants with myopia (1.03 ± 0.71 D vs. 0.13 ± 0.37 D), emmetropia (1.03 ± 0.71 D vs. 0.32 ± 0.43 D), or astigmatism (1.03 ± 0.71 D vs. 0.13 ± 0.44 D). A population-based study in China found a larger SE change after cycloplegia in participants with moderate to high hyperopia (SE difference, mean ± SD: 2.98 ± 1.65 D) [

3]. For participants with myopia of at least -2.00 D, Zhao et al. (2004) [

3] reported an SE difference of 0.41 ± 0.46 D, which is larger than the difference observed in the current study (SE difference: 0.13 ± 0.37 D) and in the study by Sanfilippo et al. (2014) [

14], where the change in SE for participants with myopia was 0.11 ± 0.47 D. This discrepancy could be explained by the different methodologies related to participant age and cycloplegic agent regimens. Zhao et al. (2004) administered 2 drops of cyclopentolate 1% to participants aged 7 to 18 years; Sanfilippo et al. (2014) used 1 drop of cyclopentolate 1% for participants aged 13 to 14 years and 1 drop of tropicamide 1% for participants aged 15 to 26 years; in our study, we administered one drop of cyclopentolate 1% to participants aged 3 to 28 years [

3,

14]. It is worth noting that the cycloplegia procedure using a single drop of cyclopentolate 1% has been empirically shown to be effective and sufficient for most individuals of European origin. In contrast, studies involving Asian or African American individuals with darker iris colour often require multiple drops of cycloplegic agents. For instance, Zhu et al. (2016) [

5] found that for 41% of participants from Inner Mongolia, China, two drops of cyclopentolate 1% administered five minutes apart were insufficient to dilate pupils beyond 6 mm. Eye care providers should be aware that, in specific cases, patients of European origin may require a second drop of cyclopentolate 1% to achieve full cycloplegia.

Various studies have demonstrated the importance of cycloplegia during comprehensive eye examination in young individuals. The selection of participants in these studies, including their ethnic origin, age, and whether they were from a population-based or non-population-based sample, as well as the cycloplegic regimen used (including the type and dosage of the agent and the interval between doses), significantly affects the amount of change in spherical equivalent (SE) and the prevalence of refractive error after cycloplegia.

4.1. Study Limitations

Participants recruited for this study were attending ophthalmology practice for reasons unrelated to the current study. Therefore, it is crucial to acknowledge that our study sample was biased, as it included participants predisposed to ocular-related dysfunction, except for those aged 3 years and 6-7 years who attended regular eye examinations. Consequently, the refractive error prevalence found in our study sample did not directly reflect the situation in the Latvian population. Currently, there are no official data available regarding the prevalence of myopia in Latvian children. We found that from 12 to 14 years of age, myopia was the predominant refractive error after cycloplegia. However, this should be interpreted cautiously, considering that the participant sample was not population-based and likely included individuals attending eye examinations due to subjective complaints. A comprehensive review encompassing 28 cross-sectional studies published between January 2013 and March 2019 reported the prevalence of myopia in schoolchildren globally [

16]. Only three of these studies were conducted in Europe. In Denmark, the prevalence of myopia in children aged 5–10 years was estimated 17.9% [

17]. In France, the prevalence of myopia was 19.6% among children aged 0–9 years and 42.7% among those aged 10–19 years [

18]. In the Netherlands, a study of 5711 six-year-old children estimated the prevalence of myopia to be 2.4%. The average prevalence of myopia in children in Asia was significantly higher than in European children (60% compared to 40% ) [

16].

4.2. Local Context

Optometrists in Latvia obtain a five-year education, comprising a three-year bachelor’s degree and a two-year master’s degree, to become certified clinical optometrists. From January 2020, Latvian optometrists have been registered as medical practitioners who, therefore, work in accordance with the local Medical Treatment Law issued by the Republic of Latvia. Currently, state-funded eye examinations for children are available in Latvia by ophthalmologists. Regulation No. 555 of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Latvia mandates that three state-funded preventive eye examinations for children must be performed by an ophthalmologist at the ages of 13-24 months, 3, and 6-7 years. Each of these examinations must include an objective refraction measurement with cycloplegia. Optometrists in Latvia participate in vision screening programs or offer paid paediatric eye examinations in optic stores without cycloplegia.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Elliott, D. Clinical Procedures in Primary Eye Care, 3rd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2007.

- Hopkins, S.; Sampson, G. P.; Hendicott, P.; Lacherez, P.; Wood, J. M. Refraction in children: A comparison of two methods of accommodation control. Optom Vis Sci. 2012, 89, 1734–1739.

- Zhao, J.; Mao, J.; Luo, R.; Li, F.; Pokharel, G. P.; Ellwein, L. B. Accuracy of noncycloplegic autorefraction in school-age children in China. Optom Vis Sci. 2004, 81, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. Y.; Wu, J. F.; Lu, T. L.; Wu, H.; Sun, W.; Wang, X. R., et al. Effect of cycloplegia on the refractive status of children: The Shandong Children Eye Study. PLoS One 2015, 10, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, D.; Guo, K.; Guo, Y., et al. Pre- and postcycloplegic refractions in children and adolescents. PLoS One 2016, 11, 1–11.

- Abrams, D.; Duke-Elder, S. Duke-Elder’s Practice of Refraction, 10th ed.; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, UK, 1993.

- Morgan, I. G.; Iribarren, R.; Fotouhi, A.; Grzybowski, A. Cycloplegic refraction is the gold standard for epidemiological studies. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015, 93, 581–585. [CrossRef]

- Yekta, A. A.; Hashemi, H.; Ostadimoghaddam, H.; Jafarzadehpur, E.; Salehabadi, S.; Sardari, S., et al. Amplitude of accommodation and add power in an adult population of Tehran, Iran. Iran J Ophthalmol. 2013, 25, 182–189.

- Fotouhi, A.; Morgan, I. G.; Iribarren, R.; Khabazkhoob, M.; Hashemi, H. Validity of noncycloplegic refraction in the assessment of refractive errors: The Tehran Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012, 90, 380–386. [CrossRef]

- Lovasik, J. V. Pharmacokinetics of topically applied cyclopentolate HCL and tropicamide. Optom Vis Sci. 1986, 63, 787–803.

- Fan, D. S. P.; Rao, S. K.; Ng, J. S. K.; Yu, C. B. O.; Lam, D. S. C. Comparative study on the safety and efficacy of different cycloplegic agents in children with darkly pigmented irides. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004, 32, 462–467. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M. N. Residual accommodation: A comparison between cyclopentolate 1% and a combination of cyclopentolate 1% and tropicamide 1%. Arch Ophthalmol. 1972, 87, 515–517.

- Li, T.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, J.; Tang, X.; Gu, X. Effect of cycloplegia on the measurement of refractive error in Chinese children. Clin Exp Optom. 2019, 102, 160–165. [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, P. G.; Chu, B. S.; Bigault, O.; Kearns, L. S.; Boon, M. Y.; Young, T. L., et al. What is the appropriate age cut-off for cycloplegia in refraction? Acta Ophthalmol. 2014, 92, e458-62.

- Manny, R. E.; Fern, K. D.; Zervas, H. J.; Cline, G. E.; Scott, S. K.; White, J. M., et al. 1% cyclopentolate hydrochloride: Another look at the time course of cycloplegia using an objective measure of the accommodative response. Optom Vis Sci. 1993, 70, 651–665.

- Grzybowski, A.; Kanclerz, P.; Tsubota, K.; Lanca, C.; Saw, S. M. A review on the epidemiology of myopia in school children worldwide. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, K.; Suhr, Thykjær, A.; Søgaard, Hansen, R.; Vestergaard, A. H.; Jacobsen, N.; Goldschmidt, E., et al. Physical activity and myopia in Danish children—The CHAMPS eye study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018, 96, 134–141. [CrossRef]

- Matamoros, E.; Ingrand, P.; Pelen, F.; Bentaleb, Y.; Weber, M.; Korobelnik, J. F., et al. Prevalence of myopia in France. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e1976. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).