Submitted:

14 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

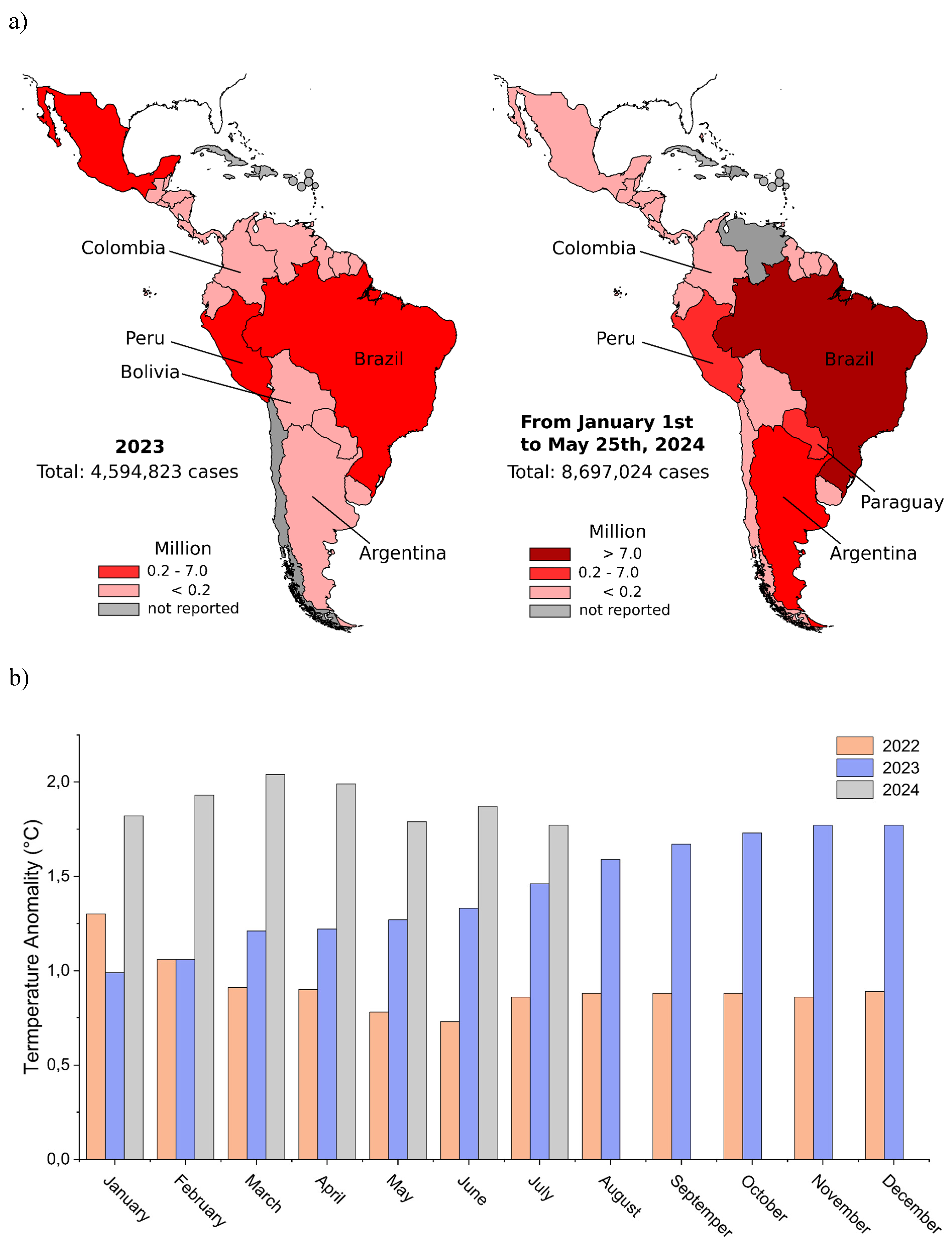

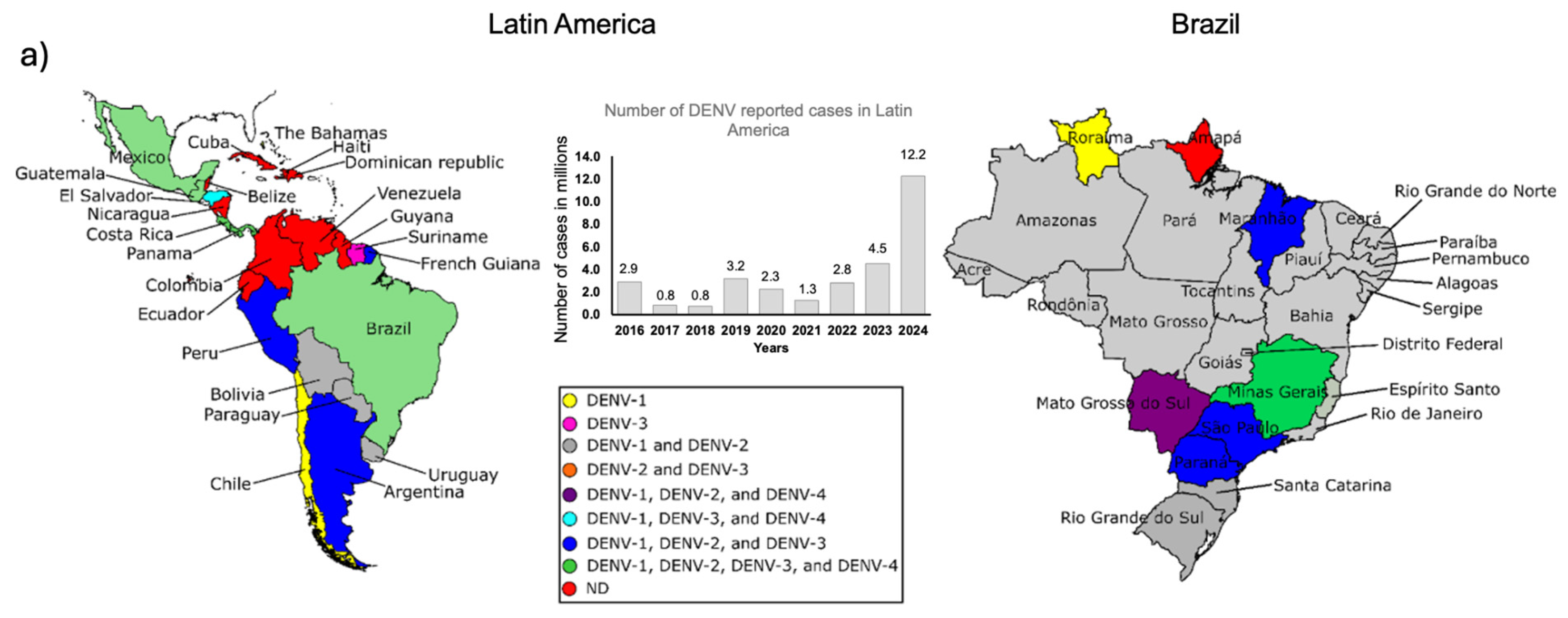

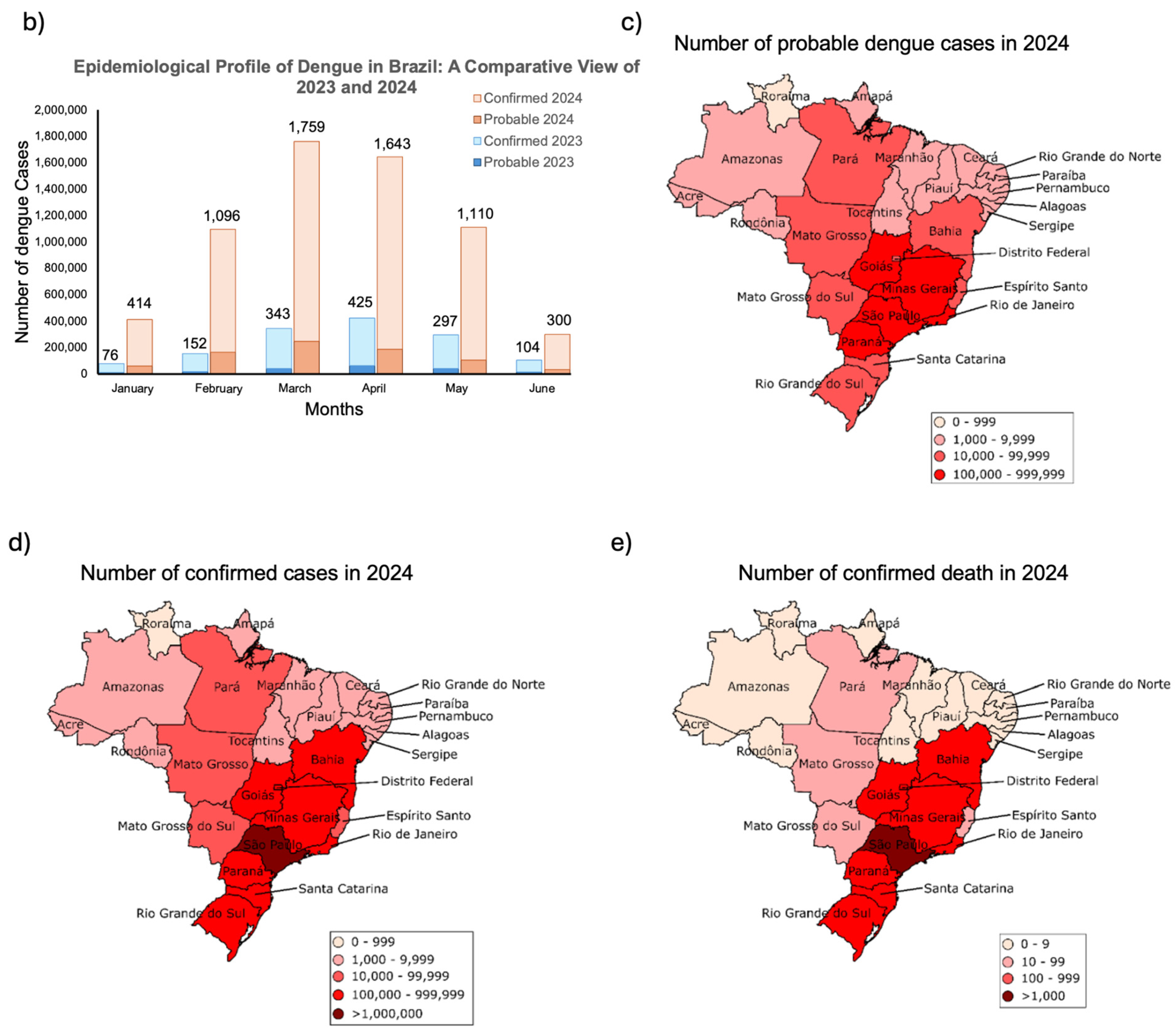

The impact of global warming on dengue outbreaks in the Latin America

| Country |

Cases (2023) |

Cases (from January to May 2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 3,064,739 | 7,253,599 |

| Argentina | 146,876 | 498,091 |

| Mexico | 277,963 | 73,532 |

| Paraguay | 63,216 | 278,827 |

| Nicaragua | 181,096 | 17,339 |

| Peru | 274,227 | 242,742 |

| Colombia | 131,784 | 157,097 |

| Bolivia | 158,744 | 36,747 |

| Ecuador | 27,838 | 27,063 |

| Guatemala | 72,358 | 21,991 |

| Chile | ND | 148 |

| Uruguay | 48 | 701 |

| Venezuela | 4,809 | ND |

| French Guiana | 2,684 | 14,084 |

| Guyana | 27,438 | 12,929 |

| Suriname | 282 | 95 |

| Nicaragua | 181,096 | 17,339 |

| Costa Rica | 30,649 | 8,851 |

| Panama | 20,924 | 6,774 |

| Cuba | ND | ND |

| Honduras | 34,050 | 20,563 |

| El Salvador | 5,788 | 2,056 |

| ND, not disclosed. | ||

| Country | Deaths caused by Dengue from January to May 2024 |

Rate of death (death/cases) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 3086 | 0.04 |

| Argentina | 343 | 0.07 |

| Paraguay | 100 | 0.04 |

| Nicaragua | ND | ND |

| Peru | 192 | 0.08 |

| Colombia | 70 | 0.05 |

| Mexico | 26 | 0.04 |

| Bolivia | 14 | 0.04 |

| Ecuador | 31 | 0.12 |

| Guatemala | 10 | 0.05 |

| Chile | ND | ND |

| Honduras | 10 | 0.05 |

| El Salvador | ND | ND |

| Guyana | 2 | 0.02 |

| Panama | 12 | 0.18 |

| Uruguay | 2 | 0.29 |

| Venezuela | ND | ND |

| French Guiana | ND | ND |

| Suriname | 3 | 3.16 |

| Costa Rica | ND | ND |

| Cuba | ND | ND |

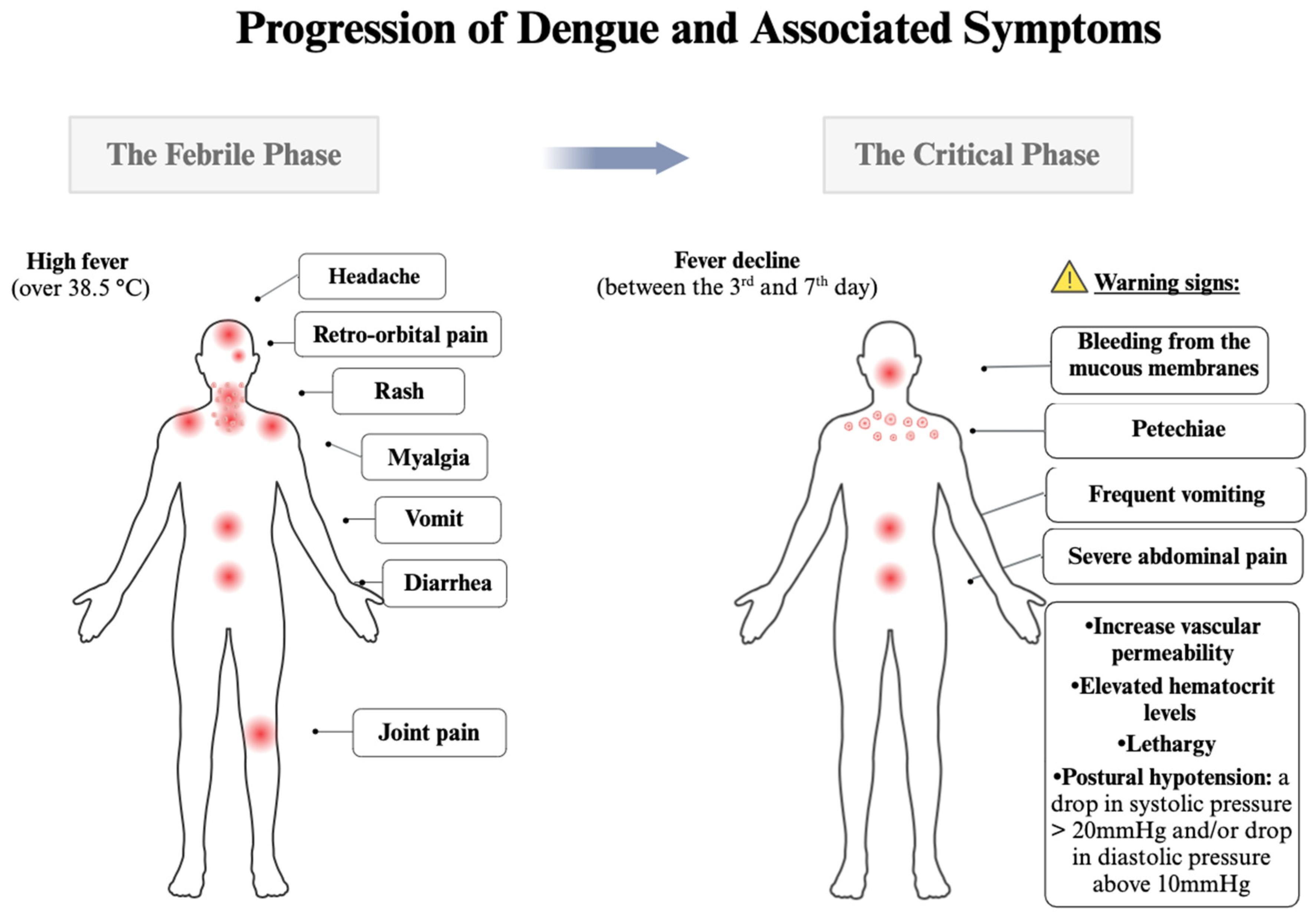

Dengue symptoms and determinants for recurrence and disease severity

Clinical management and therapeutic intervention in Dengue infection in Brazil

| Signs of shock | Clinical approach | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A |

- | • Care is provided at Primary Health Care Units (Urgent Care); • The patient is advised to undergo home treatment with oral hydration, and if symptomatic, the doctor may recommend the use of the analgesics and antipyretics Dipyrone and Paracetamol. It is important to note that during the treatment of Dengue fever, drugs from Salicylate class and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, as well as corticosteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, are not prescribed due to the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. |

[85,87,91,94] |

| Group B |

Patients presenting two or more clinical signs of the acute phase in addition to spontaneous bleeding, which can be indicated by petechiae, gingival bleeding and ecchymosis. |

The care occurs in a Secondary Health Care Unit equipped with an on-observation bed, where they are required to stay hospitalized for a minimum of 12 h. During this time, they receive oral or intravenous hydration and undergo a complete blood count to monitor their hematocrit levels. |

[85,94] |

| Group C |

Here symptoms may arise that may indicate the progression of the disease to a more serious clinical condition that includes lethargy, severe abdominal pain, postural hypotension, frequent vomiting, bleeding from the mucous membranes, progressive increase in the hematocrit levels and decrease of the platelets levels. |

• The patient should be transferred to a Tertiary Health Care Unit (Reference Hospital with greater technical support); • Will receive more rigorous intravenous hydration with physiological saline or Ringer Lactate 1 to 3 times a day, and clinical reassessment should occur hourly with hematocrit evaluation after 2 h. |

[85,94] |

| Group D |

Intended for patients presenting signs of shock: convergent blood pressure (Differential BP <20mm Hg), arterial hypotension, cyanosis, rapid pulse, and slow capillary refill. |

• The patient should receive more rigorous intravenous hydration at any healthcare facility and be immediately transferred to a Tertiary Health Care Unit (Reference Hospital with ICU beds). • Immediate intravenous hydration with an isotonic solution is advised (the procedure may be repeated up to three times as needed), followed by clinical reassessment every 15-30 min, hematocrit reassessment after two hours, and evaluation of blood pressure, pulse, and urinary output. • If there is improvement, the patient will undergo treatment designated for group C. • If the treatment is ineffective, the patient will undergo hematocrit evaluation, assessment for signs of congestive heart failure, metabolic acidosis, and monitoring of platelet levels, liver enzymes, serum albumin, assessment of renal function, and imaging tests. In this group, depending on the symptoms, there may be medical indications for analgesics and antipyretics, and diuretics for symptom reversal. |

[85,91,94] |

Measures adopted in Brazil to mitigate DENV cases

Dengue vaccines

Diagnosis test

| Diagnostic test timeline (days after symptom onset) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method principle | Primary Infection (PI) | Secondary Infection (SI) | Time to obtain the result | ||

| Capillary fragility | Tourniquet Test | - from 0 to 7 days • Se = 11.9 to 19.1 % in DF and 63 to 83% in DHF [140,160] • Sp = 86.4 to 88.9 % [140,160] in DF and 60 % in DHF [161] |

min | ||

| Virus or virus product detection | Virus isolation | - from 0 to 4 days • Se = 85.3 % [162] - from 4 days onwards • Se = 65.4 % [162] |

≥ one week | ||

| • Se = 91.0 % [162] | • Se = 77.6 % [162] | ||||

| RT-PCR or RT-qPCR | - from 0 to 5 days • Se = 90 to 100 % [150,147,147,149] • Sp = 100 % [150] - from 5 days onwards • Se = 38 to 100 % [150] • Sp = 100 % [150] |

around one day | |||

| NS1 protein detection | ELISA (serum) | - from 0 to 7 days • Se = 93.9 to 100 % [154] - from 7 to 9 days • Se = 85.7 to 93.9 % [154] |

- from 0 to 3 days • Se = 88.6 % [154] -from 3 to 5 days • Se = 54.1 % [154] |

around one day | |

| RDT (serum) | • Se = 80.3 % [163] • Sp = 100 % [163] |

• Se = 55.1 % [163] • Sp = 100 % [163] |

min | ||

| - from 0 to 3 days • Se = 76.7 to 83.3 % [164] - from 4 days onwards • Se = 47.6 to 76.2 % [164] | |||||

| Antibody detection | IgM detection | ELISA (serum) | - from 4 to 7 days • Se = 55 % [165] - from 7 days onwards • Se = 94 % [165] |

- from 4 to 7 days • Se = 47 % [165] - from 7 days onwards • Se = 78 % [165] (SI patients have a lower concentration of IgM than PI) |

around one day |

| RDT (serum) | - from 0 to 3 days • Se = 3.3 % [164] • Sp = 100 % [164] - from 4 days onwards • Se = 23.8 to 38.1 % [164] • Sp = 100 % [164] |

min | |||

| IgG detection | RDT (serum) | - From 3 to 7 days • Se = 31.82 to 40.91 % [166] • Sp = 95.24 to 100 % [166] |

- From 3 to 7 days • Se = 82.76 to 95.4 % [166] • Sp = 95.24 to 100 % [166] |

min | |

Oropouche Fever in Latin America: Rising Incidence, Clinical Overlap with Dengue, and Emerging Public Health Challenges

Dengue’s emergence in Europe: a changing epidemiological landscape

Conclusion

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO-WHO Expert Committee on Zoonoses Zoonoses: Report of the FAO-WHO Expert Committee on Zoonoses, 3rd, Geneva, 1966; 1967; ISBN 9789241203784.

- George, A.M.; Ansumana, R.; de Souza, D.K.; Niyas, V.K.M.; Zumla, A.; Bockarie, M.J. Climate Change and the Rising Incidence of Vector-Borne Diseases Globally. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 139, 143–145. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C. Climate Change Is Also a Health Crisis - These 3 Graphics Explain Why. Nature 2023, 624, 14–15. [CrossRef]

- Alied, M.; Endo, P.T.; Aquino, V.H.; Vadduri, V.V.; Huy, N.T. Latin America in the Clutches of an Old Foe: Dengue. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 27, 102788. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Gupta, S.K.; Singh, H. Surveillance of Zika and Dengue Viruses in Field-Collected Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes from Different States of India. Virology 2022, 574, 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Laverdeur, J.; Desmecht, D.; Hayette, M.-P.; Darcis, G. Dengue and Chikungunya: Future Threats for Northern Europe? Front Epidemiol 2024, 4, 1342723. [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H.; Michie, A.; Sasmono, R.T.; Imrie, A. Dengue: A Minireview. Viruses 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, T.J.; Panda, P.K.; Wolford, R.W. Dengue Fever. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Paz-Bailey, G.; Adams, L.E.; Deen, J.; Anderson, K.B.; Lc., K. Website. Lancet 2024, 403, 667–682. [CrossRef]

- Arthropod-Borne and Rodent-Borne Viral Diseases. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 1985, 719, 1–116.

- Young, P.R. Arboviruses: A Family on the Move. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1062, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.Y.; Balasuriya, U.B.R.; Lee, C.-K. Zoonotic Encephalitides Caused by Arboviruses: Transmission and Epidemiology of Alphaviruses and Flaviviruses. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2014, 3, 58–77. [CrossRef]

- Hollidge, B.S.; González-Scarano, F.; Soldan, S.S. Arboviral Encephalitides: Transmission, Emergence, and Pathogenesis. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010, 5, 428–442. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.C.; Reisen, W.K. Present and Future Arboviral Threats. Antiviral Res. 2010, 85, 328–345. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guan, W.; Liu, H. Subgenomic Flaviviral RNAs of Dengue Viruses. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, A.; Manoharan, M. Dengue Virus. In Emerging and Reemerging Viral Pathogens; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 281–359 ISBN 9780128194003.

- Drugs Targeting Structural and Nonstructural Proteins of the Chikungunya Virus: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129949. [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, E.-Y.; Charniga, K.; Rueda, A.; Dorigatti, I.; Mendez, Y.; Hamlet, A.; Carrera, J.-P.; Cucunubá, Z.M. The Epidemiology of Mayaro Virus in the Americas: A Systematic Review and Key Parameter Estimates for Outbreak Modelling. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009418. [CrossRef]

- Martins-Filho, P.R.; Soares-Neto, R.F.; de Oliveira-Júnior, J.M.; Alves Dos Santos, C. The Underdiagnosed Threat of Oropouche Fever amidst Dengue Epidemics in Brazil. Lancet Reg Health Am 2024, 32, 100718. [CrossRef]

- Cattarino, L.; Rodriguez-Barraquer, I.; Imai, N.; Cummings, D.A.T.; Ferguson, N.M. Mapping Global Variation in Dengue Transmission Intensity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Kularatne, S.A.; Dalugama, C. Dengue Infection: Global Importance, Immunopathology and Management. Clin. Med. 2022, 22, 9–13. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-de-Lima, V.H.; Lima-Camara, T.N. Natural Vertical Transmission of Dengue Virus in Aedes Aegypti and Aedes Albopictus: A Systematic Review. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 77. [CrossRef]

- Tauil, P.L. [Critical aspects of dengue control in Brazil]. Cad. Saude Publica 2002, 18, 867–871. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Bambrick, H.; Frentiu, F.D.; Devine, G.; Yakob, L.; Williams, G.; Hu, W. Projecting the Future of Dengue under Climate Change Scenarios: Progress, Uncertainties and Research Needs. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008118. [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.W.; Comrie, A.C.; Ernst, K. Climate and Dengue Transmission: Evidence and Implications. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 1264–1272. [CrossRef]

- Combined Effects of Hydrometeorological Hazards and Urbanisation on Dengue Risk in Brazil: A Spatiotemporal Modelling Study. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021, 5, e209–e219. [CrossRef]

- Dengue Overview: An Updated Systemic Review. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1625–1642. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Vasilakis, N. Dengue--Quo Tu et Quo Vadis? Viruses 2011, 3, 1562–1608. [CrossRef]

- Bashyam, H.S.; Green, S.; Rothman, A.L. Dengue Virus-Reactive CD8+ T Cells Display Quantitative and Qualitative Differences in Their Response to Variant Epitopes of Heterologous Viral Serotypes. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 2817–2824. [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Riaz, Z.; Saeed, S.; Ishaque, U.; Sultana, M.; Faiz, Z.; Shafqat, Z.; Shabbir, S.; Ashraf, S.; Marium, A. Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: A Growing Global Menace. J. Water Health 2023, 21, 1632–1650. [CrossRef]

- Brathwaite Dick, O.; San Martín, J.L.; Montoya, R.H.; del Diego, J.; Zambrano, B.; Dayan, G.H. The History of Dengue Outbreaks in the Americas. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 87, 584–593. [CrossRef]

- Juan, C. Dengue Fever: Strategies for Preventing Dengue and Bite Transmission Via Mosquitoes; Independently Published, 2024; ISBN 9798876916952.

- Cristodulo, R.; Luoma-Overstreet, G.; Leite, F.; Vaca, M.; Navia, M.; Durán, G.; Molina, F.; Zonneveld, B.; Perrone, S.V.; Barbagelata, A.; et al. Dengue Myocarditis: A Case Report and Major Review. Glob. Heart 2023, 18, 41. [CrossRef]

- Aedes Albopictus - Current Known Distribution: October 2023 Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/aedes-albopictus-current-known-distribution-october-2023 (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Gamez, S.; Antoshechkin, I.; Mendez-Sanchez, S.C.; Akbari, O.S. The Developmental Transcriptome of , a Major Worldwide Human Disease Vector. G3 2020, 10, 1051–1062. [CrossRef]

- Weerakoon, K.G.; Kularatne, S.A.; Edussuriya, D.H.; Kodikara, S.K.; Gunatilake, L.P.; Pinto, V.G.; Seneviratne, A.B.; Gunasena, S. Histopathological Diagnosis of Myocarditis in a Dengue Outbreak in Sri Lanka, 2009. BMC Res. Notes 2011, 4, 268. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Singh, K.; Ravi Kumar, Y.S.; Roy, R.; Phadnis, S.; Meena, V.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Verma, B. Dengue Virus Pathogenesis and Host Molecular Machineries. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 43. [CrossRef]

- Madhry, D.; Pandey, K.K.; Kaur, J.; Rawat, Y.; Sapra, L.; Y S, R.K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Verma, B. Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Dengue Virus-Host Interaction. Front. Biosci. 2021, 13, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.G.; Gubler, D.J.; Izquierdo, A.; Martinez, E.; Halstead, S.B. Dengue Infection. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2016, 2, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Gubler, D.J.; Ooi, E.E.; Vasudevan, S.; Farrar, J. Dengue and Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever, 2nd Edition; CABI, 2014; ISBN 9781845939649.

- Tan, P.C.; Rajasingam, G.; Devi, S.; Omar, S.Z. Dengue Infection in Pregnancy: Prevalence, Vertical Transmission, and Pregnancy Outcome. Obstet Gynecol 2008, 111, 1111–1117. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Soni, S.; Aggarwal, S.; Saini, A.S. Vertical Transmission of Dengue—A Case Report. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India 2013, 64, 1–2. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-de-Lima, V.H.; Andrade, P.D.S.; Thomazelli, L.M.; Marrelli, M.T.; Urbinatti, P.R.; Almeida, R.M.M. de S.; Lima-Camara, T.N. Silent Circulation of Dengue Virus in Aedes Albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) Resulting from Natural Vertical Transmission. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 3855. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.; Mourya, D.T.; Sharma, R.C. Persistence of Dengue-3 Virus through Transovarial Transmission Passage in Successive Generations of Aedes Aegypti Mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2002, 67, 158–161. [CrossRef]

- Shroyer, D.A. Vertical Maintenance of Dengue-1 Virus in Sequential Generations of Aedes Albopictus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1990, 6, 312–314.

- Kok, B.H.; Lim, H.T.; Lim, C.P.; Lai, N.S.; Leow, C.Y.; Leow, C.H. Dengue Virus Infection - a Review of Pathogenesis, Vaccines, Diagnosis and Therapy. Virus Res. 2023, 324, 199018. [CrossRef]

- Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control: New Edition; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2009; ISBN 9789241547871.

- Zerfu, B.; Kassa, T.; Legesse, M. Epidemiology, Biology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, and Diagnosis of Dengue Virus Infection, and Its Trend in Ethiopia: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Trop. Med. Health 2023, 51, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kalayanarooj, S. Clinical Manifestations and Management of Dengue/DHF/DSS. Trop. Med. Health 2011, 39, 83–87. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Sharma, P.; Garg, R.K.; Atam, V.; Singh, M.K.; Mehrotra, H.S. Neurological Complications of Dengue Fever: Experience from a Tertiary Center of North India. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2011, 14, 272–278. [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A. Água e mudanças climáticas. Estud. av. 2008, 22, 83–96. [CrossRef]

- Southern Brazil Has Seen an Increase of up to 30% in Average Annual Rainfall over the Last Three Decades Available onlinhttps://www.gov.br/planalto/en/latest-news/2024/05/southern-brazil-has-seen-an-increase-of-up-to-30-in-average-annual-rainfall-over-the-last-three-decades (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Diallo, D.; Diouf, B.; Gaye, A.; NDiaye, E.H.; Sene, N.M.; Dia, I.; Diallo, M. Dengue Vectors in Africa: A Review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09459. [CrossRef]

- Pirani, M.; Lorenz, C.; de Azevedo, T.S.; Barbosa, G.L.; Blangiardo, M.; Chiaravalloti-Neto, F. Effects of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation and Seasonal Weather Conditions on Aedes Aegypti Infestation in the State of São Paulo (Brazil): A Bayesian Spatio-Temporal Study. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2024, 18, e0012397. [CrossRef]

- Website Available online: (https://www.paho.org/pt/topicos/dengue).

- Dengue: diagnóstico e manejo clínico: adulto e criança Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- BRASIL Painel de Monitoramento das Arboviroses Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/a/aedes-aegypti/monitoramento-das-arboviroses/painel (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Dengue Available online: https://www3.paho.org/data/index.php/en/mnu-topics/indicadores-dengue-en.html (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- PAHO Situation Report No 20 - Dengue Epidemiological Situation in the Region of the Americas - Epidemiological Week 20, 2024 Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/situation-report-no-20-dengue-epidemiological-situation-region-americas-epidemiological (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- Gutiérrez, L.A. PAHO/WHO Data - Dengue serotypes by country Available online: https://www3.paho.org/data/index.php/en/mnu-topics/indicadores-dengue-en/dengue-nacional-en/517-dengue-serotypes-en.html (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- BRASIL Centro de Operações de Emergências (COE) Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/a/arboviroses/informe-semanal/informe-semanal-no-02-coe (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- Khanam, A.; Gutiérrez-Barbosa, H.; Lyke, K.E.; Chua, J.V. Immune-Mediated Pathogenesis in Dengue Virus Infection. Viruses 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Waickman, A.T.; Lu, J.Q.; Fang, H.; Waldran, M.J.; Gebo, C.; Currier, J.R.; Ware, L.; Van Wesenbeeck, L.; Verpoorten, N.; Lenz, O.; et al. Evolution of Inflammation and Immunity in a Dengue Virus 1 Human Infection Model. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabo5019. [CrossRef]

- Dengue Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/d/dengue/dengue (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Scully, C. Persistent Metallic Taste. Br. Dent. J. 2013, 214, 217–218. [CrossRef]

- Sansone, N.M.S.; Boschiero, M.N.; Marson, F.A.L. Dengue Outbreaks in Brazil and Latin America: The New and Continuing Challenges. Int J Infect Dis 2024, 147, 107192. [CrossRef]

- Burattini, M.N.; Lopez, L.F.; Coutinho, F.A.B.; Siqueira, J.B., Jr; Homsani, S.; Sarti, E.; Massad, E. Age and Regional Differences in Clinical Presentation and Risk of Hospitalization for Dengue in Brazil, 2000-2014. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2016, 71, 455–463. [CrossRef]

- Paixão, E.S.; Costa, M. da C.N.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Rasella, D.; Cardim, L.L.; Brasileiro, A.C.; Teixeira, M.G.L.C. Trends and Factors Associated with Dengue Mortality and Fatality in Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2015, 48, 399–405. [CrossRef]

- Yung, C.-F.; Lee, K.-S.; Thein, T.-L.; Tan, L.-K.; Gan, V.C.; Wong, J.G.X.; Lye, D.C.; Ng, L.-C.; Leo, Y.-S. Dengue Serotype-Specific Differences in Clinical Manifestation, Laboratory Parameters and Risk of Severe Disease in Adults, Singapore. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 92, 999–1005. [CrossRef]

- Ten Bosch, Q.A.; Clapham, H.E.; Lambrechts, L.; Duong, V.; Buchy, P.; Althouse, B.M.; Lloyd, A.L.; Waller, L.A.; Morrison, A.C.; Kitron, U.; et al. Contributions from the Silent Majority Dominate Dengue Virus Transmission. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1006965. [CrossRef]

- Duong, V.; Lambrechts, L.; Paul, R.E.; Ly, S.; Lay, R.S.; Long, K.C.; Huy, R.; Tarantola, A.; Scott, T.W.; Sakuntabhai, A.; et al. Asymptomatic Humans Transmit Dengue Virus to Mosquitoes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 14688–14693. [CrossRef]

- Bos, S.; Zambrana, J.V.; Duarte, E.; Graber, A.L.; Huffaker, J.; Montenegro, C.; Premkumar, L.; Gordon, A.; Kuan, G.; Balmaseda, A.; et al. Serotype-Specific Epidemiological Patterns of Inapparent versus Symptomatic Primary Dengue Virus Infections: A 17-Year Cohort Study in Nicaragua. Lancet Infect Dis 2024. [CrossRef]

- Vicente, C.R.; Herbinger, K.-H.; Fröschl, G.; Malta Romano, C.; de Souza Areias Cabidelle, A.; Cerutti Junior, C. Serotype Influences on Dengue Severity: A Cross-Sectional Study on 485 Confirmed Dengue Cases in Vitória, Brazil. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 320. [CrossRef]

- Henrique Ferreira Sucupira, P.; Silveira Ferreira, M.; Santos Coutinho-da-Silva, M.; Alves Bicalho, K.; Carolina Campi-Azevedo, A.; Pedro Brito-de-Sousa, J.; Peruhype-Magalhães, V.; Rios, M.; Konduru, K.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A.; et al. Serotype-Associated Immune Response and Network Immunoclusters in Children and Adults during Acute Dengue Virus Infection. Cytokine 2023, 169, 156306. [CrossRef]

- Rowe, E.K.; Leo, Y.-S.; Wong, J.G.X.; Thein, T.-L.; Gan, V.C.; Lee, L.K.; Lye, D.C. Challenges in Dengue Fever in the Elderly: Atypical Presentation and Risk of Severe Dengue and Hospital-Acquired Infection [corrected]. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2777. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Schiøler, K.L.; Jepsen, M.R.; Ho, C.-K.; Li, S.-H.; Konradsen, F. Dengue Outbreaks in High-Income Area, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, 2003-2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1603–1611. [CrossRef]

- Paz-Bailey, G.; Sánchez-González, L.; Torres-Velasquez, B.; Jones, E.S.; Perez-Padilla, J.; Sharp, T.M.; Lorenzi, O.; Delorey, M.; Munoz-Jordan, J.L.; Tomashek, K.M.; et al. Predominance of Severe Plasma Leakage in Pediatric Patients With Severe Dengue in Puerto Rico. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1949–1958. [CrossRef]

- Hober, D.; Poli, L.; Roblin, B.; Gestas, P.; Chungue, E.; Granic, G.; Imbert, P.; Pecarere, J.L.; Vergez-Pascal, R.; Wattre, P. Serum Levels of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha (TNF-Alpha), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and Interleukin-1 Beta (IL-1 Beta) in Dengue-Infected Patients. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993, 48, 324–331. [CrossRef]

- Soo, K.-M.; Khalid, B.; Ching, S.-M.; Chee, H.-Y. Meta-Analysis of Dengue Severity during Infection by Different Dengue Virus Serotypes in Primary and Secondary Infections. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0154760. [CrossRef]

- Estofolete, C.F.; Versiani, A.F.; Dourado, F.S.; Milhim, B.H.G.A.; Pacca, C.C.; Silva, G.C.D.; Zini, N.; Santos, B.F.D.; Gandolfi, F.A.; Mistrão, N.F.B.; et al. Influence of Previous Zika Virus Infection on Acute Dengue Episode. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011710. [CrossRef]

- Musso, D.; Ko, A.I.; Baud, D. Zika Virus Infection - After the Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1444–1457. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Feng, S.; Lu, K.; Zhu, W.; Sun, H.; Niu, G. Oropouche Virus: A Neglected Global Arboviral Threat. Virus Res. 2024, 341, 199318. [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R.K.; Mishra, S.; Satapathy, P.; Kandi, V.; Tuglo, L.S. Surging Oropouche Virus (OROV) Cases in the Americas: A Public Health Challenge. New Microbes New Infect 2024, 59, 101243. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Risk Assessment Related to Oropouche Virus (OROV) in the Region of the Americas, 9 February 2024 Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/public-health-risk-assessment-related-oropouche-virus-orov-region-americas-9-february-2024 (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- B A Seixas, J.; Giovanni Luz, K.; Pinto Junior, V. [Clinical Update on Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Dengue]. Acta Med. Port. 2024, 37, 126–135. [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, S.; de Silva, N.L.; Weeratunga, P.; Rodrigo, C.; Fernando, S.D. Prophylactic and Therapeutic Interventions for Bleeding in Dengue: A Systematic Review. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 111, 433–439. [CrossRef]

- Jasamai, M.; Yap, W.B.; Sakulpanich, A.; Jaleel, A. Current Prevention and Potential Treatment Options for Dengue Infection. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 22, 440–456. [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.M.; Santos, N.C.; Martins, I.C. Dengue and Zika Viruses: Epidemiological History, Potential Therapies, and Promising Vaccines. Trop Med Infect Dis 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Miner, J.J.; Diamond, M.S. Zika Virus Pathogenesis and Tissue Tropism. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 134–142. [CrossRef]

- Begum, F.; Das, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Mal, S.; Ray, U. Insight into the Tropism of Dengue Virus in Humans. Viruses 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL Diretrizes Nacionais Para a Prevenção E Controle de Epidemias de Dengue. Brasília, DF: MS, 2009 Available online: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/diretrizes_nacionais_prevencao_controle_dengue (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- PAHO Guidelines for the Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/55867 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- WHO Dengue Guias Para El Diagnóstico, Tratamiento, Prevención Y Control: Nueva Edición Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44504 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Stanley, S.M.; Khera, H.K.; Chandrasingh, S.; George, C.E.; Mishra, R.K. A Comprehensive Review of Dengue with a Focus on Emerging Solutions for Precision and Timely Detection. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127613. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL Ministério da Saúde-Saúde de A a Z-Dengue Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/d/dengue/dengue (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- OPAS Alerta Epidemiológico-Aumento de casos de dengue na Região das Américas Available online: https://www.paho.org/pt/documentos/alerta-epidemiologico-aumento-casos-dengue-na-regiao-das-americas-16-fevereiro-2024 (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- BRASIL Ministério da Saúde entrega nova remessa de vacinas da dengue Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2024/maio/ministerio-da-saude-entrega-nova-remessa-de-vacinas-da-dengue (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- BRASIL Ministério da Saúde elabora plano para enfrentamento da dengue 2024/2025 Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2024/maio/ministerio-da-saude-elabora-plano-para-enfrentamento-da-dengue-2024-2025 (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Website Available online: BRASIL. Combate ao mosquito. Ministério da Saúde https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/campanhas-da-saude/2023/combate-ao-mosquito/combate-ao-mosquito (2023).

- Muir, L.E.; Thorne, M.J.; Kay, B.H. Aedes Aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Vision: Spectral Sensitivity and Other Perceptual Parameters of the Female Eye. J Med Entomol 1992, 29, 278–281. [CrossRef]

- Taniyama, K.; Hori, M. Lethal Effect of Blue Light on Asian Tiger Mosquito, Aedes Albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10100. [CrossRef]

- Salles, T.; Corrêa, I.; Guimarães-Ribeiro, V.; Carvalho, E.; Moreira, M. LED Colour Trap for Aedes Aegypti Control. Recent Pat Biotechnol 2021, 15, 227–331. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL Saiba como é utilizado o fumacê no combate ao mosquito da dengue Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2024/marco/saiba-como-e-utilizado-o-fumace-no-combate-ao-mosquito-da-dengue (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Pinto, S.B.; Riback, T.I.S.; Sylvestre, G.; Costa, G.; Peixoto, J.; Dias, F.B.S.; Tanamas, S.K.; Simmons, C.P.; Dufault, S.M.; Ryan, P.A.; et al. Effectiveness of Wolbachia-Infected Mosquito Deployments in Reducing the Incidence of Dengue and Other Aedes-Borne Diseases in Niterói, Brazil: A Quasi-Experimental Study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2021, 15, e0009556. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Dos Santos, G.; Durovni, B.; Saraceni, V.; Souza Riback, T.I.; Pinto, S.B.; Anders, K.L.; Moreira, L.A.; Salje, H. Estimating the Effect of the wMel Release Programme on the Incidence of Dengue and Chikungunya in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A Spatiotemporal Modelling Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2022, 22, 1587–1595. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, S.B.G.; Guimarães-Ribeiro, V.; Rodriguez, J.V.G.; Dorand, F.A.P.S.; Salles, T.S.; Sá-Guimarães, T.E.; Alvarenga, E.S.L.; Melo, A.C.A.; Almeida, R.V.; Moreira, M.F. RNAi-Based Bioinsecticide for Aedes Mosquito Control. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 4038. [CrossRef]

- Utarini, A.; Indriani, C.; Ahmad, R.A.; Tantowijoyo, W.; Arguni, E.; Ansari, M.R.; Supriyati, E.; Wardana, D.S.; Meitika, Y.; Ernesia, I.; et al. Efficacy of Wolbachia-Infected Mosquito Deployments for the Control of Dengue. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 2177–2186. [CrossRef]

- Velez, I.D.; Tanamas, S.K.; Arbelaez, M.P.; Kutcher, S.C.; Duque, S.L.; Uribe, A.; Zuluaga, L.; Martínez, L.; Patiño, A.C.; Barajas, J.; et al. Reduced Dengue Incidence Following City-Wide wMel Wolbachia Mosquito Releases throughout Three Colombian Cities: Interrupted Time Series Analysis and a Prospective Case-Control Study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2023, 17, e0011713. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL Você sabe o que é o Método Wolbachia? Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-com-ciencia/noticias/2024/maio/voce-sabe-o-que-e-o-metodo-wolbachia (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- World Mosquito Program Sobre O Método Wolbachia Available online: https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/sobre-o-metodo-wolbachia (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- BRASIL Ministério da Saúde incorpora vacina contra a dengue no SUS Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2023/dezembro/ministerio-da-saude-incorpora-vacina-contra-a-dengue-no-sus (accessed on 16 June 2024).

- Butantan, I. Instituto Butantan-Portal Do Butantan Available online: https://butantan.gov.br/covid/butantan-tira-duvida/tira-duvida-noticias/vacina-da-dengue-deve-proteger-de-todos-os-subtipos-da-doenca--entenda-a-complexidade-do-ensaio-clinico (accessed on 2024).

- Kallás, E.G.; Cintra, M.A.T.; Moreira, J.A.; Patiño, E.G.; Braga, P.E.; Tenório, J.C.V.; Infante, V.; Palacios, R.; de Lacerda, M.V.G.; Batista Pereira, D.; et al. Live, Attenuated, Tetravalent Butantan-Dengue Vaccine in Children and Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Buerano, C.C.; Morita, K. Single Dose of Dengvaxia Vaccine: Is It a Cause for Alarm? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 670–671. [CrossRef]

- Forrat, R.; Dayan, G.H.; DiazGranados, C.A.; Bonaparte, M.; Laot, T.; Capeding, M.R.; Sanchez, L.; Coronel, D.L.; Reynales, H.; Chansinghakul, D.; et al. Analysis of Hospitalized and Severe Dengue Cases Over the 6 Years of Follow-up of the Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine (CYD-TDV) Efficacy Trials in Asia and Latin America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1003–1012. [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Papadimitriou, A.; Winkle, P.; Segall, N.; Levin, M.; Doust, M.; Johnson, C.; Lucksinger, G.; Fierro, C.; Pickrell, P.; et al. Immunogenicity and Safety of Lyophilized and Liquid Dengue Tetravalent Vaccine Candidate Formulations in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Phase 2 Clinical Trial. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 2456–2464. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.J.; Yoon, I.-K. A Review of Dengvaxia®: Development to Deployment. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 2295–2314. [CrossRef]

- Guirakhoo, F.; Weltzin, R.; Chambers, T.J.; Zhang, Z.X.; Soike, K.; Ratterree, M.; Arroyo, J.; Georgakopoulos, K.; Catalan, J.; Monath, T.P. Recombinant Chimeric Yellow Fever-Dengue Type 2 Virus Is Immunogenic and Protective in Nonhuman Primates. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 5477–5485. [CrossRef]

- Guirakhoo, F.; Arroyo, J.; Pugachev, K.V.; Miller, C.; Zhang, Z.X.; Weltzin, R.; Georgakopoulos, K.; Catalan, J.; Ocran, S.; Soike, K.; et al. Construction, Safety, and Immunogenicity in Nonhuman Primates of a Chimeric Yellow Fever-Dengue Virus Tetravalent Vaccine. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 7290–7304. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Flores, J.M.; Reyes-Sandoval, A.; Salazar, M.I. Dengue Vaccines: An Update. BioDrugs 2022, 36, 325–336. [CrossRef]

- Villar, L.; Dayan, G.H.; Arredondo-García, J.L.; Rivera, D.M.; Cunha, R.; Deseda, C.; Reynales, H.; Costa, M.S.; Morales-Ramírez, J.O.; Carrasquilla, G.; et al. Efficacy of a Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine in Children in Latin America. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 113–123. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, R.U.; Dayrit, M.M.; Alfonso, C.R.; Ong, M.M.A. Public Trust and the COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign: Lessons from the Philippines as It Emerges from the Dengvaxia Controversy. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage. 2021, 36, 2048–2055. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.S.; Winkle, P.; Faccin, A.; Nordio, F.; LeFevre, I.; Tsoukas, C.G. An Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial of TAK-003, a Live Attenuated Dengue Tetravalent Vaccine, in Healthy US Adults: Immunogenicity and Safety When Administered during the Second Half of a 24-Month Shelf-Life. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2254964. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Vimal, N.; Angmo, N.; Sengupta, M.; Thangaraj, S. Dengue Vaccination: Towards a New Dawn of Curbing Dengue Infection. Immunol. Invest. 2023, 52, 1096–1149. [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Llorens, X.; Biswal, S.; Borja-Tabora, C.; Fernando, L.; Liu, M.; Wallace, D.; Folschweiller, N.; Reynales, H.; LeFevre, I.; TIDES Study Group Effect of the Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine TAK-003 on Sequential Episodes of Symptomatic Dengue. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023, 108, 722–726. [CrossRef]

- Bengolea, A.; Scigliano, C.; Ramos-Rojas, J.T.; Rada, G.; Catalano, H.N.; Izcovich, A. Effectiveness and Safety of the Tetravalent TAK-003 Dengue Vaccine: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2024, 84, 689–707.

- Angelin, M.; Sjölin, J.; Kahn, F.; Ljunghill Hedberg, A.; Rosdahl, A.; Skorup, P.; Werner, S.; Woxenius, S.; Askling, H.H. Qdenga® - A Promising Dengue Fever Vaccine; Can It Be Recommended to Non-Immune Travelers? Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 54, 102598. [CrossRef]

- Sirivichayakul, C.; Barranco-Santana, E.A.; Esquilin-Rivera, I.; Oh, H.M.L.; Raanan, M.; Sariol, C.A.; Shek, L.P.; Simasathien, S.; Smith, M.K.; Velez, I.D.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine Candidate in Healthy Children and Adults in Dengue-Endemic Regions: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Study. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213, 1562–1572. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.J. Is New Dengue Vaccine Efficacy Data a Relief or Cause for Concern? NPJ Vaccines 2023, 8, 55. [CrossRef]

- Flacco, M.E.; Bianconi, A.; Cioni, G.; Fiore, M.; Calò, G.L.; Imperiali, G.; Orazi, V.; Tiseo, M.; Troia, A.; Rosso, A.; et al. Immunogenicity, Safety and Efficacy of the Dengue Vaccine TAK-003: A Meta-Analysis. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, S.S. Development of TV003/TV005, a Single Dose, Highly Immunogenic Live Attenuated Dengue Vaccine; What Makes This Vaccine Different from the Sanofi-Pasteur CYDTM Vaccine? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2016, 15, 509–517. [CrossRef]

- Weiskopf, D.; Angelo, M.A.; Bangs, D.J.; Sidney, J.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; de Silva, A.D.; Lindow, J.C.; Diehl, S.A.; Whitehead, S.; et al. The Human CD8+ T Cell Responses Induced by a Live Attenuated Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine Are Directed against Highly Conserved Epitopes. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 120–128. [CrossRef]

- Kallas, E.G.; Precioso, A.R.; Palacios, R.; Thomé, B.; Braga, P.E.; Vanni, T.; Campos, L.M.A.; Ferrari, L.; Mondini, G.; da Graça Salomão, M.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of the Tetravalent, Live-Attenuated Dengue Vaccine Butantan-DV in Adults in Brazil: A Two-Step, Double-Blind, Randomised Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 839–850. [CrossRef]

- Angelo, M.A.; Grifoni, A.; O’Rourke, P.H.; Sidney, J.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; de Silva, A.D.; Phillips, E.; Mallal, S.; Diehl, S.A.; et al. Human CD4 T Cell Responses to an Attenuated Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine Parallel Those Induced by Natural Infection in Magnitude, HLA Restriction, and Antigen Specificity. J. Virol. 2017, 91. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, M.L.; Cintra, M.A.T.; Moreira, J.A.; Patiño, E.G.; Braga, P.E.; Tenório, J.C.V.; de Oliveira Alves, L.B.; Infante, V.; Silveira, D.H.R.; de Lacerda, M.V.G.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Butantan-DV in Participants Aged 2-59 Years through an Extended Follow-up: Results from a Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3, Multicentre Trial in Brazil. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Muller, D.A.; Depelsenaire, A.C.I.; Young, P.R. Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis of Dengue Virus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, S89–S95. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, C.J.; Lorenzi, O.D.; Colón, L.; García, A.S.; Santiago, L.M.; Rivera, R.C.; Bermúdez, L.J.C.; Báez, F.O.; Aponte, D.V.; Tomashek, K.M.; et al. Utility of the Tourniquet Test and the White Blood Cell Count to Differentiate Dengue among Acute Febrile Illnesses in the Emergency Room. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1400. [CrossRef]

- Kalayanarooj, S.; Vaughn, D.W.; Nimmannitya, S.; Green, S.; Suntayakorn, S.; Kunentrasai, N.; Viramitrachai, W.; Ratanachu-eke, S.; Kiatpolpoj, S.; Innis, B.L.; et al. Early Clinical and Laboratory Indicators of Acute Dengue Illness. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 176, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Montes y Gómez, M.; Escalante, H.J.; Segura, A.; de Dios Murillo, J. Advances in Artificial Intelligence - IBERAMIA 2016: 15th Ibero-American Conference on AI, San José, Costa Rica, November 23-25, 2016, Proceedings; Springer, 2016; ISBN 9783319479552.

- Furlan, N.B.; Tukasan, C.; Estofolete, C.F.; Nogueira, M.L.; da Silva, N.S. Low Sensitivity of the Tourniquet Test for Differential Diagnosis of Dengue: An Analysis of 28,000 Trials in Patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 627. [CrossRef]

- Mayxay, M.; Phetsouvanh, R.; Moore, C.E.; Chansamouth, V.; Vongsouvath, M.; Sisouphone, S.; Vongphachanh, P.; Thaojaikong, T.; Thongpaseuth, S.; Phongmany, S.; et al. Predictive Diagnostic Value of the Tourniquet Test for the Diagnosis of Dengue Infection in Adults. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 127–133. [CrossRef]

- St John, A.L.; Rathore, A.P.S. Adaptive Immune Responses to Primary and Secondary Dengue Virus Infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 218–230. [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.F.; Ooi, E.E. Diagnosis of Dengue: An Update. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2012, 10, 895–907. [CrossRef]

- Avrami, S.; Hoffman, T.; Meltzer, E.; Lustig, Y.; Schwartz, E. Comparison of Clinical and Laboratory Parameters of Primary vs Secondary Dengue Fever in Travellers. J. Travel Med. 2023, 30. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Lustig, Y.; Sklan, E.H.; Schwartz, E. The Role of NS1 Protein in the Diagnosis of Flavivirus Infections. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Lanciotti, R.S.; Calisher, C.H.; Gubler, D.J.; Chang, G.J.; Vorndam, A.V. Rapid Detection and Typing of Dengue Viruses from Clinical Samples by Using Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 545–551. [CrossRef]

- Chien, L.-J.; Liao, T.-L.; Shu, P.-Y.; Huang, J.-H.; Gubler, D.J.; Chang, G.-J.J. Development of Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase PCR Assays to Detect and Serotype Dengue Viruses. J Clin Microbiol 2006, 44, 1295–1304. [CrossRef]

- Iani, F.C. de M.; Caetano, A.C.B.; Cocovich, J.C.W.; Amâncio, F.F.; Pereira, M.A.; Adelino, T.É.R.; Caldas, S.; Silva, M.V.F.; Pereira, G. de C.; Duarte, M.M. Dengue Diagnostics: Serious Inaccuracies Are Likely to Occur If Pre-Analytical Conditions Are Not Strictly Followed. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2021, 115, e200287. [CrossRef]

- Najioullah, F.; Viron, F.; Césaire, R. Evaluation of Four Commercial Real-Time RT-PCR Kits for the Detection of Dengue Viruses in Clinical Samples. Virol J 2014, 11, 164. [CrossRef]

- Monitoring and Improving the Sensitivity of Dengue Nested RT-PCR Used in Longitudinal Surveillance in Thailand. J. Clin. Virol. 2015, 63, 25–31. [CrossRef]

- Cecchetto, J.; Fernandes, F.C.B.; Lopes, R.; Bueno, P.R. The Capacitive Sensing of NS1 Flavivirus Biomarker. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 949–956. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, M.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S.K. Flavivirus NS1: A Multifaceted Enigmatic Viral Protein. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 131. [CrossRef]

- Peeling, R.W.; Artsob, H.; Pelegrino, J.L.; Buchy, P.; Cardosa, M.J.; Devi, S.; Enria, D.A.; Farrar, J.; Gubler, D.J.; Guzman, M.G.; et al. Evaluation of Diagnostic Tests: Dengue. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, S30–S38. [CrossRef]

- Andries, A.-C.; Duong, V.; Ong, S.; Ros, S.; Sakuntabhai, A.; Horwood, P.; Dussart, P.; Buchy, P. Evaluation of the Performances of Six Commercial Kits Designed for Dengue NS1 and Anti-Dengue IgM, IgG and IgA Detection in Urine and Saliva Clinical Specimens. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Lanciotti, R.S.; Kosoy, O.L.; Laven, J.J.; Velez, J.O.; Lambert, A.J.; Johnson, A.J.; Stanfield, S.M.; Duffy, M.R. Genetic and Serologic Properties of Zika Virus Associated with an Epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 1232–1239. [CrossRef]

- Changal, K.H.; Raina, A.H.; Raina, A.; Raina, M.; Bashir, R.; Latief, M.; Mir, T.; Changal, Q.H. Differentiating Secondary from Primary Dengue Using IgG to IgM Ratio in Early Dengue: An Observational Hospital Based Clinico-Serological Study from North India. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Bäck, A.T.; Lundkvist, A. Dengue Viruses - an Overview. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2013, 3. [CrossRef]

- Ayukekbong, J.A.; Oyero, O.G.; Nnukwu, S.E.; Mesumbe, H.N.; Fobisong, C.N. Value of Routine Dengue Diagnosis in Endemic Countries. World J Virol 2017, 6, 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.J.; Nisalak, A.; Anderson, K.B.; Libraty, D.H.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Vaughn, D.W.; Putnak, R.; Gibbons, R.V.; Jarman, R.; Endy, T.P. Dengue Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test (PRNT) in Primary and Secondary Dengue Virus Infections: How Alterations in Assay Conditions Impact Performance. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 81, 825–833. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.C.; Oliveira, G.L.; Nunes, L.I.; Guedes Filho, L.A.; Prado, R.S.; Henriques, H.R.; Vieira, A.J.C. Evaluation of the Diagnostic Value of the Tourniquet Test in Predicting Severe Dengue Cases in a Population from Belo Horizonte, State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2013, 46, 542–546. [CrossRef]

- Grande, A.J.; Reid, H.; Thomas, E.; Foster, C.; Darton, T.C. Tourniquet Test for Dengue Diagnosis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10. [CrossRef]

- Jarman, R.G.; Nisalak, A.; Anderson, K.B.; Klungthong, C.; Thaisomboonsuk, B.; Kaneechit, W.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Gibbons, R.V. Factors Influencing Dengue Virus Isolation by C6/36 Cell Culture and Mosquito Inoculation of Nested PCR-Positive Clinical Samples. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 84, 218. [CrossRef]

- Tricou, V.; Vu, H.T.T.; Quynh, N.V.N.; Nguyen, C.V.V.; Tran, H.T.; Farrar, J.; Wills, B.; Simmons, C.P. Comparison of Two Dengue NS1 Rapid Tests for Sensitivity, Specificity and Relationship to Viraemia and Antibody Responses. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Luvira, V.; Thawornkuno, C.; Lawpoolsri, S.; Thippornchai, N.; Duangdee, C.; Ngamprasertchai, T.; Leaungwutiwong, P. Diagnostic Performance of Dengue NS1 and Antibodies by Serum Concentration Technique. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Laboratory Diagnosis of Primary and Secondary Dengue Infection. J. Clin. Virol. 2004, 31, 179–184. [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.S.; Kwak, S.Y.; May, W.L.; Yang, D.J.; Nam, J.; Lim, C.S. Comparative Evaluation of Three Dengue Duo Rapid Test Kits to Detect NS1, IgM, and IgG Associated with Acute Dengue in Children in Myanmar. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0213451. [CrossRef]

- Sah, R.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, S.; Golmei, P.; Rahaman, S.A.; Mehta, R.; Ferraz, C.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Oropouche Fever Outbreak in Brazil: An Emerging Concern in Latin America. Lancet Microbe 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sciancalepore, S.; Schneider, M.C.; Kim, J.; Galan, D.I.; Riviere-Cinnamond, A. Presence and Multi-Species Spatial Distribution of Oropouche Virus in Brazil within the One Health Framework. Trop Med Infect Dis 2022, 7. [CrossRef]

- Emergence of Oropouche Fever in Latin America: A Narrative Review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e439–e452. [CrossRef]

- PAHO Epidemiological Alert Oropouche in the Region of the Americas: Vertical Transmission Event under Investigation in Brazil - 17 July 2024 Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/epidemiological-alert-oropouche-region-americas-vertical-transmission-event-under (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- das Neves Martins, F.E.; Chiang, J.O.; Nunes, B.T.D.; Ribeiro, B. de F.R.; Martins, L.C.; Casseb, L.M.N.; Henriques, D.F.; de Oliveira, C.S.; Maciel, E.L.N.; Azevedo, R. da S.; et al. Newborns with Microcephaly in Brazil and Potential Vertical Transmission of Oropouche Virus: A Case Series. Lancet Infect Dis 2024. [CrossRef]

- Garcia Filho, C.; Lima Neto, A.S.; Maia, A.M.P.C.; da Silva, L.O.R.; Cavalcante, R. da C.; Monteiro, H. da S.; Marques, K.C.A.; Oliveira, R. de S.; Gadelha, S. de A.C.; Nunes de Melo, D.; et al. A Case of Vertical Transmission of Oropouche Virus in Brazil. N Engl J Med 2024. [CrossRef]

- Feitoza, L.H.M.; de Carvalho, L.P.C.; da Silva, L.R.; Meireles, A.C.A.; Rios, F.G.F.; Silva, G.S.; de Paulo, P.F.M.; Pessoa, F.A.C.; de Medeiros, J.F.; Julião, G.R. Influence of Meteorological and Seasonal Parameters on the Activity of Culicoides Paraensis (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae), an Annoying Anthropophilic Biting Midge and Putative Vector of Oropouche Virus in Rondônia, Brazilian Amazon. Acta Trop. 2023, 243, 106928. [CrossRef]

- Febre do Oropouche Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/f/febre-do-oropouche (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Silva-Júnior, E.F. da Oropouche Virus - The “Newest” Invisible Public Enemy? Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2024, 109, 117797. [CrossRef]

- Parra Barrera, E.L.; Reales-González, J.; Salas, D.; Reyes Santamaría, E.; Bello, S.; Rico, A.; Pardo, L.; Parra, E.; Rodriguez, K.; Alarcon, Z.; et al. Fatal Acute Undifferentiated Febrile Illness among Clinically Suspected Leptospirosis Cases in Colombia, 2016-2019. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011683. [CrossRef]

- Gaillet, M.; Pichard, C.; Restrepo, J.; Lavergne, A.; Perez, L.; Enfissi, A.; Abboud, P.; Lambert, Y.; Ma, L.; Monot, M.; et al. Outbreak of Oropouche Virus in French Guiana. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2711–2714. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Alvarez, D.; Escobar, L.E. Oropouche Fever, an Emergent Disease from the Americas. Microbes Infect. 2018, 20, 135–146. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M. de S.; Figueiredo, L.T.M.; Naveca, F.G.; Monte, R.L.; Lessa, N.; Pinto de Figueiredo, R.M.; Gimaque, J.B. de L.; Pivoto João, G.; Ramasawmy, R.; Mourão, M.P.G. Identification of Oropouche Orthobunyavirus in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Three Patients in the Amazonas, Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 86, 732–735. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.F.; Serra, O.P.; Heinen, L.B. da S.; Zuchi, N.; Souza, V.C. de; Naveca, F.G.; Santos, M.A.M. dos; Slhessarenko, R.D. Detection of Oropouche Virus Segment S in Patients and inCulex Quinquefasciatus in the State of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2015, 110, 745–754. [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, H.; Bozidis, P.; Franks, A.; Papadopoulou, C. Oropouche Fever: A Review. Viruses 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Dengue- Global Situation Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON498#:~:text=Dengue%20is%20not%20endemic%20in,%2C%20Italy%2C%20Portugal%20and%20Spain. (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Aedes Invasive Mosquitoes - Current Known Distribution: October 2023 Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/aedes-invasive-mosquitoes-current-known-distribution-october-2023 (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Prudhomme, J.; Fontaine, A.; Lacour, G.; Gantier, J.-C.; Diancourt, L.; Velo, E.; Bino, S.; Reiter, P.; Mercier, A. The Native European Mosquito Species Can Transmit Chikungunya Virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 962–972. [CrossRef]

- LaTourrette, K.; Garcia-Ruiz, H. Determinants of Virus Variation, Evolution, and Host Adaptation. Pathogens 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Autochthonous Vectorial Transmission of Dengue Virus in Mainland EU/EEA, 2010-Present Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/dengue/surveillance-and-disease-data/autochthonous-transmission-dengue-virus-eueea (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Naddaf, M. Mosquito-Borne Diseases Are Surging in Europe - How Worried Are Scientists? Nature 2024, 633, 749. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.S.; Chaturvedi, H.K. A Retrospective Study of Environmental Predictors of Dengue in Delhi from 2015 to 2018 Using the Generalized Linear Model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8109. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).