Submitted:

24 June 2024

Posted:

04 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background and Motivation

2.1. Unpalleting Systems in Industrial Environments

2.2. Computational Vision Techniques for Object Detection and Localization

2.3. Related Work

3. Methodology

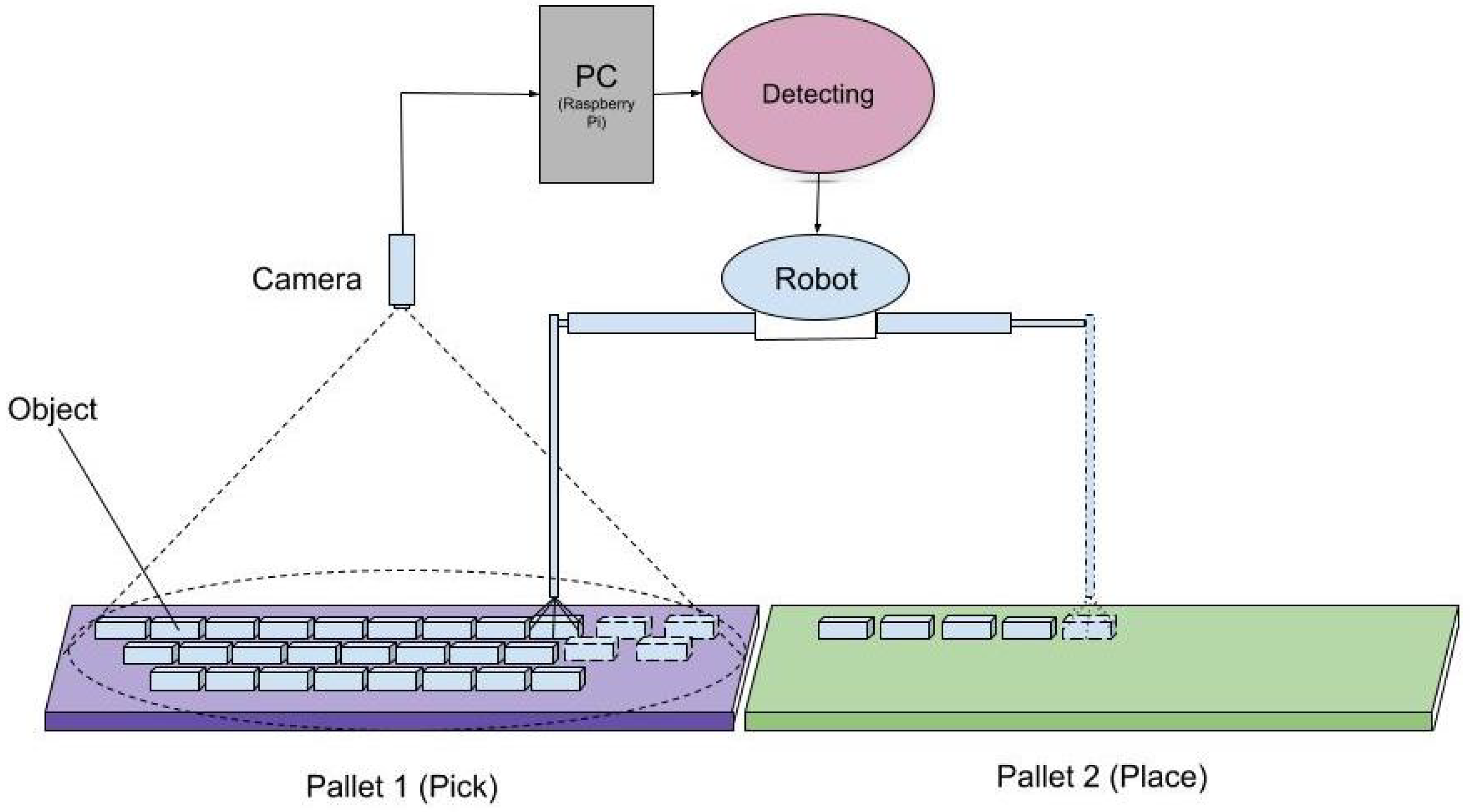

3.1. Experimental Setup

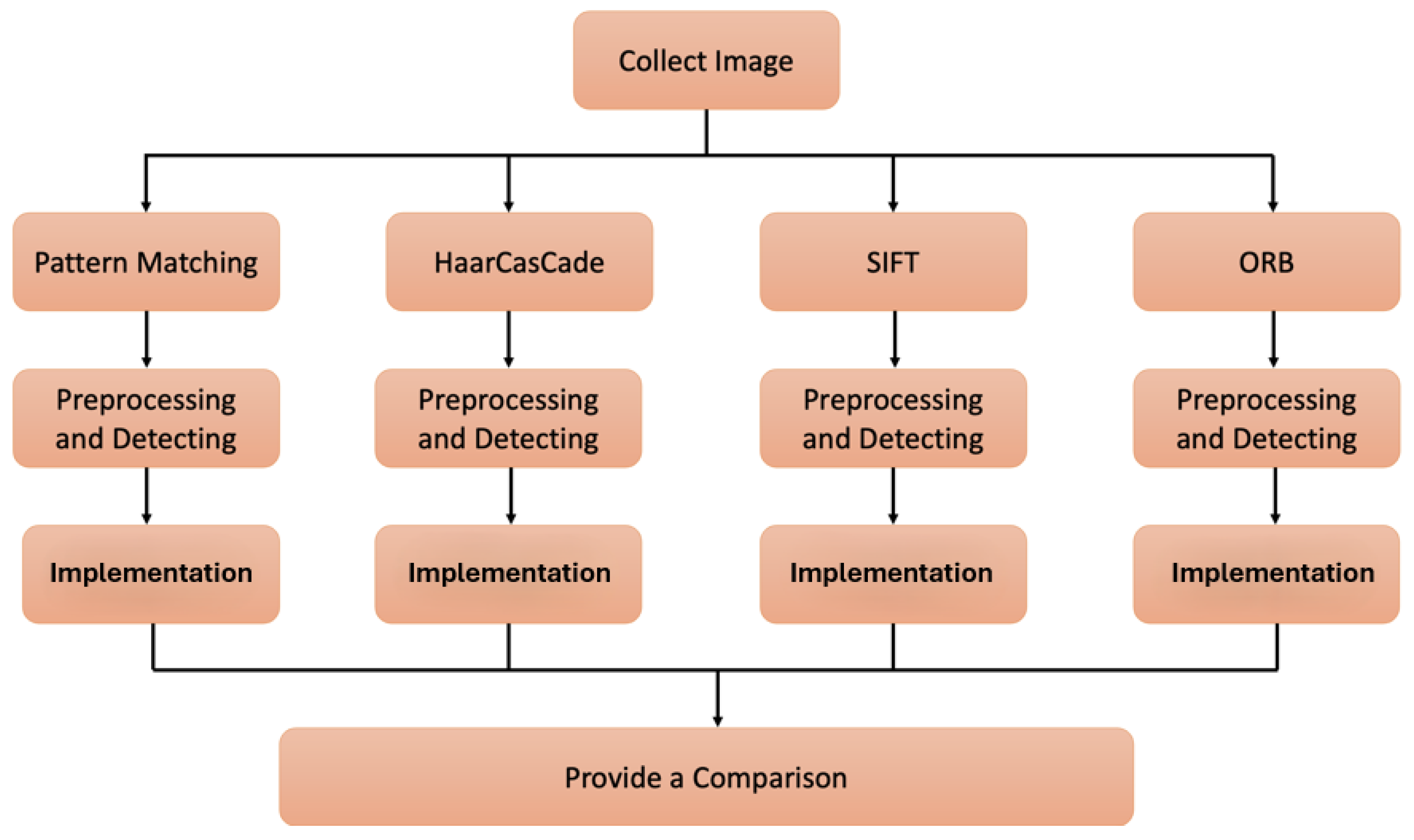

- Collecting the image data.

- Preprocessing and generating feature vectors using four feature descriptors Pattern Matching, Haar Cascade, SIFT and ORB individually.

- Make a comparison between outcome algorithms.

- Finding the best algorithm.

3.2. Pattern Matching

- Template Generation: Templates are generated by reading template images and creating various rotations to enhance detection robustness end to encapsulate the visual characteristics of objects within an image. This involves capturing template images and applying transformations such as rotations to create variations that enhance the system’s capacity to detect objects across diverse orientations.

- Image Processing: The system captured an image from the camera and converted it to grayscale, which not only simplifies subsequent computations but also facilitates robust feature extraction, essential for accurate pattern matching and proceeded with template matching.

- Template Matching: Central to the pattern matching process is template matching, realized through mathematical operations such as cross-correlation or normalized cross-correlation.

Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC)

- is the correlation value at the point .

- is the pixel value in the template at position .

- is the mean of the pixel values in the template.

- is the pixel value in the image at position .

- is the mean of the pixel values in the region of the image being compared with the template.

Procedure for Template Matching

- Calculate the mean of the template:where m and n are the dimensions of the template.

- Calculate the mean of the image region:where p and q are the dimensions of the region.

- Calculate the numerator of the NCC:

- Calculate the denominator of the NCC:

- Calculate the correlation value for each position in the image.

- 4.

-

Non-maximum Suppression (NMS): the algorithm removes redundant bounding boxes using non-maximum suppression, ensuring only the most relevant boxes are considered. Modern object detectors usually follow a three-step recipe:

- proposing a search space of windows (exhaustive by sliding window or sparser using proposals)

- scoring/refining the window with a classifier/regressor,

- merging the bounding boxes around each detected object into a single best representative box.

This last stage is commonly referred to as “non-maximum suppression” and is a crucial step in pattern-matching algorithms to refine the detected object locations and eliminate redundant matches. NMS can be used to find distinctive feature points in an image. To improve the repeatability of a detected corner across multiple images, the corner is often selected as a local maximum whose cornerness is significantly higher than the close-by second-highest peak [19]. NMS with a small neighborhood size can produce an oversupply of initial peaks. These peaks are then compared with other peaks in a larger neighborhood to retain strong ones only. The initial peaks can be sorted during NMS to facilitate the later pruning step.For some applications such as multi-view image matching, an evenly distributed set of interest points for matching is desirable. An oversupplied set of NMS point features can be given to an adaptive non-maximal suppression process [6], which reduces cluttered corners to improve their spatial distribution.Consider a similarity score matrix obtained after template matching, where u and v represent the coordinates of the image. Each element denotes the similarity score at the corresponding location in the image. The non-maximum suppression algorithm can be described as followsIn this formulation:- represents the resulting score after non-maximum suppression.

- For each pixel location the algorithm checks whether the similarity score at that location is greater than or equal to the scores of its neighboring pixels in all eight directions (i.e., top-left, top, top-right, left, right, bottom-left, bottom, bottom-right).

- If the similarity score at is greater than or equal to the scores of all its neighbors, it is retained as a local maximum and assigned the same value.

- Otherwise, if is not a local maximum, it is suppressed by setting its value to zero.

This process ensures that only the highest-scoring pixel in each local neighbourhood is retained, effectively removing redundant detections, and preserving only the most salient object instances in the image. By employing non-maximum suppression, pattern-matching algorithms can produce more accurate and concise results, facilitating precise object localization and recognition within complex visual scenes.

- 5.

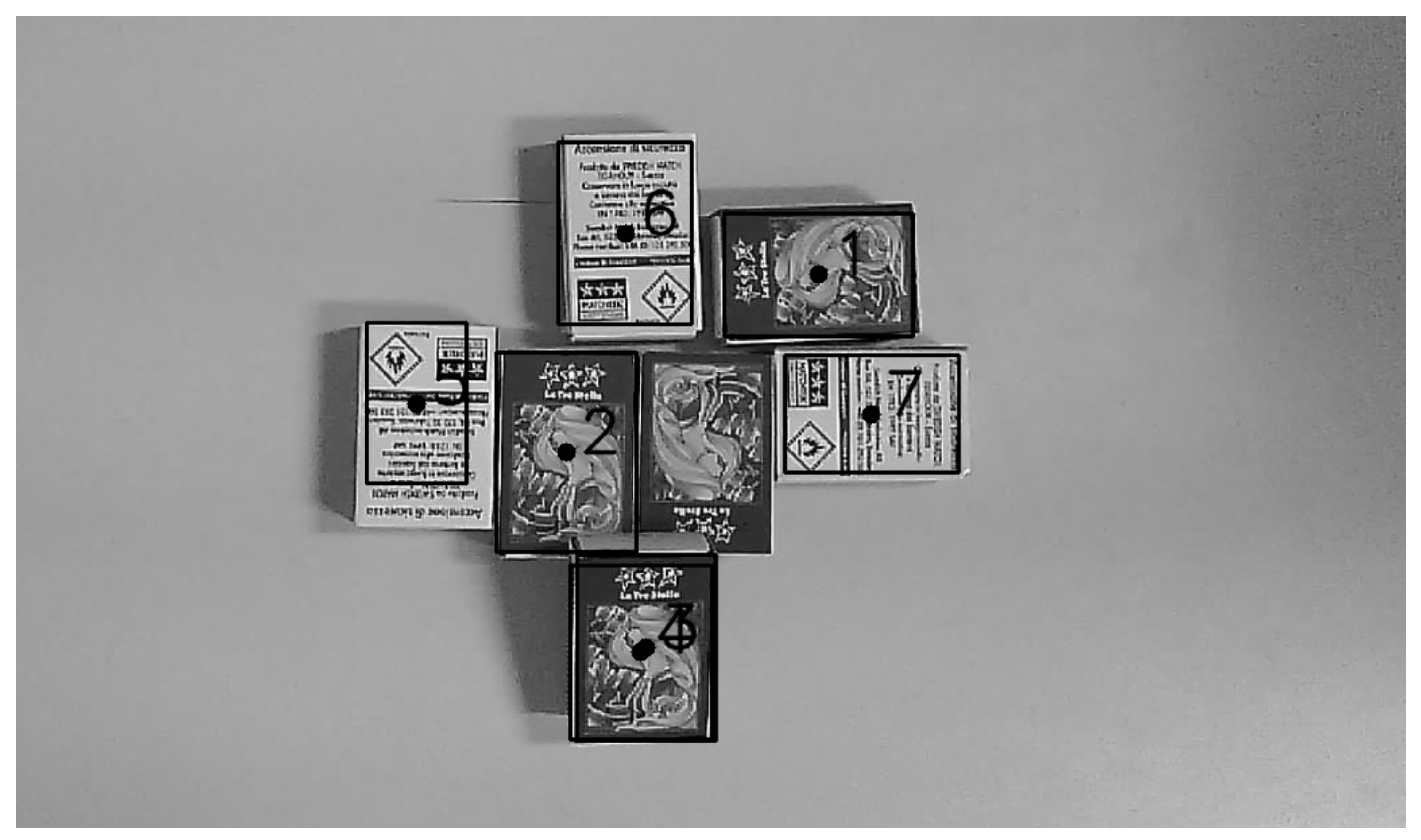

- Result Visualization: The final result was displayed, indicating the detected objects’ centres and their corresponding identification numbers (Figure 3).

Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT)

- Scale-space Extrema Detection

- Keypoint Localization

- Orientation Assignment

- Keypoint Descriptor

- SIFT Feature Extraction: SIFT key points and descriptors are extracted from both the template and target images. This step involves analyzing the local intensity gradients of the images to identify distinctive key points and generate corresponding descriptors.

- Looping Over Image Regions: The code iterates over different regions of the target image using nested loops. Within each iteration, a region of interest (ROI) is defined based on the current position of the loop.

- Matching and Filtering: Matches between descriptors were filtered, and a minimum match count was set to ensure accurate object detection.

- Filtering Matches: A ratio test is applied to filter out good matches from the initial set of matches. Only matches with a distance ratio less than a certain threshold are considered as good matches. The threshold refers to a distance ratio used in the ratio test for filtering good matches. The ratio test compares the distances between the nearest descriptor and the second one in each descriptor.

- Homography Estimation: Using the RANSAC algorithm (Random Sample Consensus), a perspective transformation matrix (M) is estimated based on the good matches. This matrix represents the geometric transformation required to align the template image with the current ROI (Region of Interest) in the target image.

- Perspective Transformation: The computed transformation matrix is used to alter the corners of the template picture such that they line up with the ROI in the target image.

- Bounding Box Computation: The minimum and maximum coordinates of the transformed corners are calculated to determine the bounding box of the detected object in the target image.

-

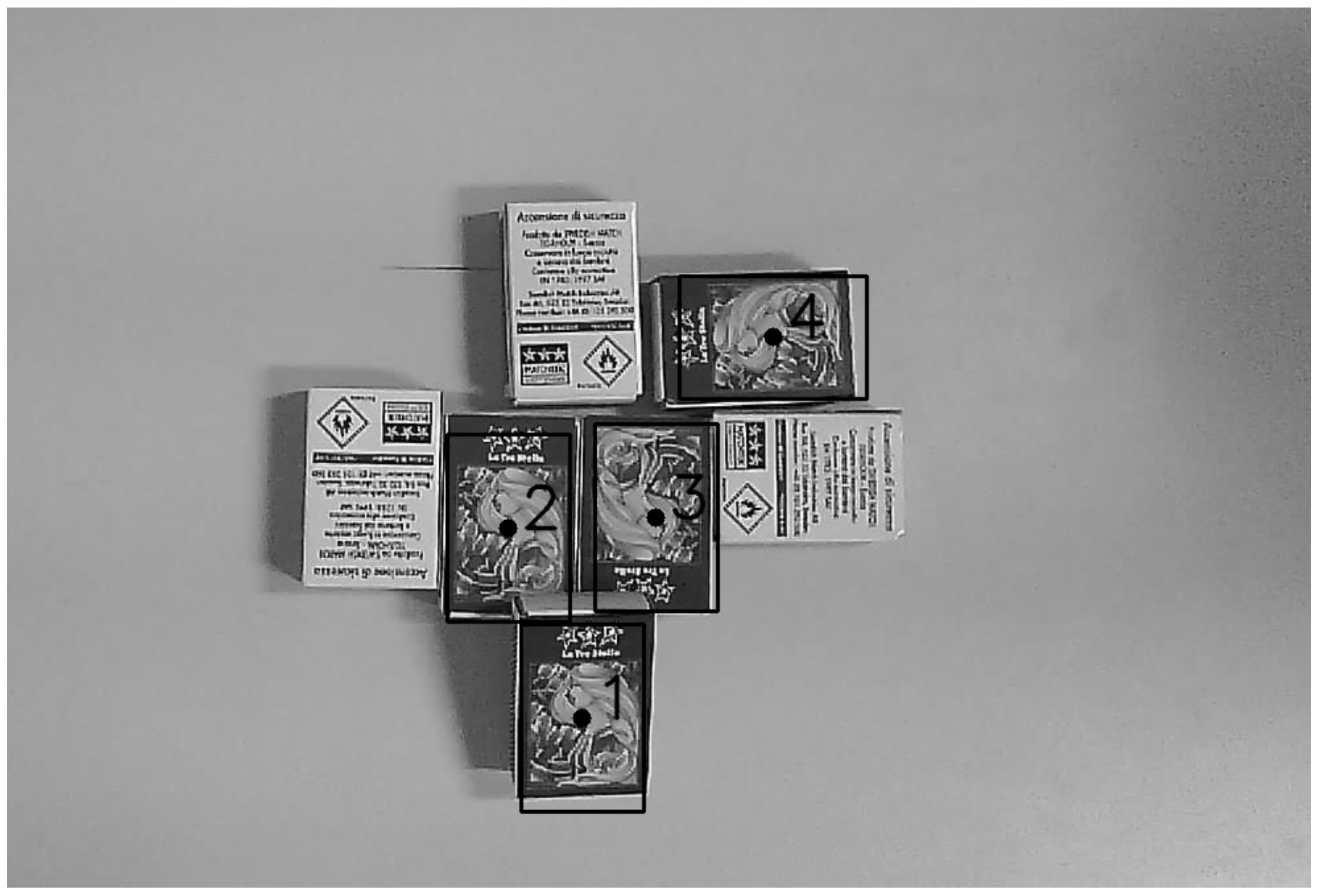

Drawing and Visualization: Finally, the bounding box and centre of the detected object are selected on the target image.Overall, the main preprocessing step used in the SIFT technique is feature extraction, and there are SIFT key points and descriptors calculated in both the template and target images. Then these descriptors are used for matching and finally object detection. In this technique, the code does not include explicit preprocessing steps such as image resizing, noise reduction, or contrast enhancement.The result of detection is shown in Figure 4.

Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF (ORB)

- Implements the ORB detector for feature extraction in both the template and target image.

- Applies a sliding window approach with a defined step size for efficient detection.

- Utilizes a Brute-Force Matcher with Hamming distance for descriptor matching.

- Filters match based on a predefined matching threshold.

- Performs non-maximum suppression to merge nearby bounding boxes.

3.5. Haar Cascade Classifiers

- Prepare Negative Images: A folder for negative images was created by copying images from a source directory. A background file (bg.txt) listed the negative images.

- Resize and Edit Images: Positive and negative images were resized to consistent dimensions (e.g., 60x100 pixels for positive images). For positive images, an option is provided to either use default dimensions or customize the size. The script renames the images and adjusts their dimensions accordingly.

- Create Positive Samples: The tool generated positive samples and related information for each positive image. The program iterates through the positive images, creating a separate directory for each image’s data. The default configuration includes parameters like angles, number of samples, width, and height.

- Merge Vector Files: Positive sample vector files were merged into a single file (mrgvec.vec) for training input.

- Train Cascade Classifier: The tool trained the Haar Cascade classifier using configuration options like the number of positive/negative samples and stages. The training process can be run in the background if specified.

- Completion: Despite a time-intensive training process, Haar Cascade exhibits effective detection performance, resulting in acceptable in proper accuracy. Moreover, it shows resilience to variations in expressions and lighting conditions, contributing to its effectiveness in real-world scenarios. Concerning its computational speed, it demonstrates quick detection post-training, with the inevitable and initial time investment required during the training phase. It requires attention to parameters such as setting variation, rotation angle and different thresholds contributing to the time-consuming tuning process. In this approach significant computational resources during the training phase, with efficient resource consumption during detection in a large number of negative images and a few positive images (Figure 6).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Accuracy

- Pattern Matching: Achieved high accuracy in object detection, with straightforward configuration by adjusting a single threshold and angle.

- SIFT: Demonstrated efficiency in finding key points, especially effective in rotation scenarios, contributing to its versatility across various applications.

- ORB: Maintained reliable detection accuracy for the front side of objects under certain conditions but showed limitations in recognizing the back part of matchboxes.

- Haar Cascade: Despite a time-intensive training process, Haar Cascade exhibited effective detection performance, resulting in acceptable accuracy.

4.2. Robustness to Variability

- Pattern Matching: Demonstrated robustness to variability, showcasing resilience to changes in object appearance, lighting, and orientation.

- SIFT: Proved robust against scale, rotation, and illumination changes, contributing to its adaptability in diverse conditions.

- ORB: Displayed limitations in recognizing specific object orientations, impacting its robustness to variability. However, it remained reliable under certain conditions.

- Haar Cascade: Showed resilience to variations in object appearance and lighting conditions, contributing to its effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

4.3. Computational Speed

- Pattern Matching: Achieved fast detection speed, taking only a few seconds for implementation.

- SIFT: Boasted a fast implementation with efficient key point detection, contributing to its real-time applicability.

- ORB: Exhibited slower execution speed, contrary to expectations for a binary method, suggesting potential performance optimizations.

- Haar Cascade: Demonstrated quick detection post-training, with the inevitable and initial time investment required during the training phase.

4.4. Detection Sensitivity

- Pattern Matching: Exhibited sensitivity to changes in the detection threshold, offering flexibility in configuration.

- SIFT: Showed sensitivity to parameter adjustments, with a relatively quick tuning process.

- ORB: Displayed sensitivity to object orientation, requiring careful parameter tuning for optimal performance.

- Haar Cascade: Required attention to parameters such as setting variation and rotation angle, contributing to the time-consuming tuning process.

4.5. Resource Consumption

- Pattern Matching, SIFT, and ORB: Demonstrated efficient resource consumption, making them suitable for practical applications.

- Haar Cascade: Required significant computational resources during the training phase, with efficient resource consumption during detection. (requiring a large number of negative images and a few positive images)

| Training Time (hrs) | Latency (sec) | Total Matches | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern Matching | 0 | 0.13 | 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Haar Classifier | 3.55 | 0.0951 | 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SIFT | 0 | 0.388 | 6 | 1.00 | 0.857 | 0.923 |

| ORB | 0 | 12.06 | 4 | 1.00 | 0.571 | 0.727 |

- Pattern Matching, SIFT and ORB: These algorithms do not require training, making them advantageous in scenarios where rapid deployment is needed.

- Haar Classifier: Requires a substantial training time of 3.55 hours, indicating an initial setup cost. However, this investment pays off with excellent detection performance.

- Haar Classifier: The fastest detection time (0.0951 sec) highlights its efficiency post-training.

- Pattern Matching: Quick detection time (0.13 sec) without the need for training makes it a strong candidate for real-time applications.

- SIFT: Moderate detection time (0.388 sec) reflects its computational complexity due to the detailed feature extraction process.

- ORB: Surprisingly, ORB takes the longest detection time (12.06 sec), which is unexpected for a binary feature descriptor. This may be attributed to implementation details or the specific test conditions.

- Pattern Matching and Haar Classifier: Both achieve the highest number of matches (7), indicating high effectiveness in object detection.

- SIFT: Slightly lower total matches (6), reflecting its robustness but also its selective nature.

- ORB: The lowest total matches (4), highlighting potential limitations in detecting all relevant objects, especially in more complex scenes.

- Precision: All four algorithms exhibit perfect precision (1.00), indicating that when they do make detections, they are consistently accurate.

- Recall: Pattern Matching and Haar Classifier achieve perfect recall (1.00), showing their ability to detect all relevant objects. SIFT has a slightly lower recall (0.857), while ORB has the lowest (0.571), indicating it misses more objects.

- F1 Score: The F1 Score combines precision and recall into a single metric. Pattern Matching and Haar Classifier both achieve the highest possible F1 score (1.00). SIFT has a respectable F1 score (0.923), while ORB lags behind at 0.727.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piccinini, P.; Prati, A.; Cucchiara, R. Real-time object detection and localization with SIFT-based clustering. Image and Vision Computing 2012, 30, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guennouni, S.; Ahaitouf, A.; Mansouri, A. A Comparative Study of Multiple Object Detection Using Haar-Like Feature Selection and Local Binary Patterns in Several Platforms. Modelling and simulation in Engineering 2015, 2015, 948960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. International journal of computer vision 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, S.; Song, W.; Yang, Y. A comparative study of small object detection algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2019 Chinese control conference (CCC). IEEE; 2019; pp. 8507–8512. [Google Scholar]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An efficient alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 2011 International conference on computer vision. Ieee; 2011; pp. 2564–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; Szeliski, R.; Winder, S. Multi-image matching using multi-scale oriented patches. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05). IEEE, 2005, Vol. 1, pp. 510–517.

- Muja, M.; Lowe, D.G. Fast approximate nearest neighbors with automatic algorithm configuration. VISAPP (1) 2009, 2, 2.

- Bay, H.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. Surf: Speeded up robust features. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2006: 9th European Conference on Computer Vision, Graz, Austria, May 7-13, 2006. Proceedings, Part I 9. Springer, 2006, pp. 404–417.

- Gue, K. Automated Order Picking. In Warehousing in the global supply chain: Advanced models, tools and applications for storage systems; Manzini, R., Ed.; Springer, 2012; pp. 151–174.

- Li, Y.; Qi, H.; Dai, J.; Ji, X.; Wei, Y. Fully convolutional instance-aware semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 2359–2367.

- Bradski, G.; Kaehler, A. Learning OpenCV: Computer vision with the OpenCV library; " O’Reilly Media, Inc.", 2008.

- Wuest, T.; Weimer, D.; Irgens, C.; Thoben, K.D. Machine learning in manufacturing: advantages, challenges, and applications. Production & Manufacturing Research 2016, 4, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Rapid object detection using a boosted cascade of simple features. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition.; p. 200120011.

- Bansal, M.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, M. 2D object recognition: a comparative analysis of SIFT, SURF and ORB feature descriptors. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, 18839–18857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 779–788.

- Bodla, N.; Singh, B.; Chellappa, R.; Davis, L.S. Soft-NMS–improving object detection with one line of code. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 5561–5569.

- Rodgers, J.L.; Nicewander, W.A. Thirteen Ways to Look at the Correlation Coefficient. The American Statistician 1988, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, C.; Mohr, R.; Bauckhage, C. Evaluation of interest point detectors. International Journal of computer vision 2000, 37, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).