1. Introduction

Nearly 20% of all mortality in industrialised countries is due to sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) [

1]. More than 356,000 people have an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States every year, and about 60% to 80% of them die before reaching the hospital [

1]. Fatalities due to SCA specifically in Greece are estimated to 9 per 10.000 citizens per year [

2] which is close to the average rate for Europe as a whole [

3].

On the other hand, a timely intervention can have a huge impact on the incident outcome. Survival can be as high as 90% if treatment starts within the first minutes after SCA. The rate drops by about 10% each minute longer [

5]. SCA can be fatal if it lasts longer than eight minutes without CPR. Brain damage can happen after just five minutes. CPR plus defibrillation is the intervention that can save a person from SCA. Using an automated external defibrillator (AED) is the best chance of helping a person survive; the shorter the time until defibrillation, the greater the chance of survival.

In an attempt to provide timely support to SCA cases, AEDs are sometimes placed in locations where SCA incidents are most probable, as for example in stadiums where large gatherings of people are combined with increased physical activity. These AEDs are typically acquired, placed and operated via private initiatives, without any central coordination or supervision. As a result, a weakness is that at a time of a potential SCA incident it is not always easy - or even possible - for a random bystander to know where the closest AED is located, if it is available/accessible at that specific time or whether someone that is properly trained to apply the AED will also be present.

Of course, to be of any use in a case of emergency, the exact location of the defibrillators needs to be known or somehow readily available to any random member of the public. To this end, services such as TheCircuit in England [

13] maintain and provide information on the network of AEDs. In Greece, in contrast, there is no corresponding governmental or government-endorsed service. The Greek Emergency Medical Services (EKAB) that one contacts in the case of a any medical emergency are not able to provide information regarding the location of AEDs. There is one private initiative that maintains a list of AEDs in Greece [

14], but the list it maintains is incomplete at best.

Indicatively, in

Figure 1 we see a sign pointing towards the location of an AED in the facilities of the Department of Digital Systems of the University of the Peloponnese; this AED is NOT included in the list of KidsSAveLives. Moreover, it is not mentioned on the department’s website, it is not mentioned on the university’s website and it does not come up in the university’s search engines. Our own team was unaware of its existence despite our interest in defibrillators, the fact that our group maintains facilities in the very same building and that two of the co-authors of this manuscript have worked and studied at that building for years. Therefore it is quite improbable that this specific AED would be of particular use in a case of suspected SCA close to the premises of our university, as there is no way for it to be known, particularly to members of the general public who reside close to the university campus but do not enter the building as part of their daily routine.

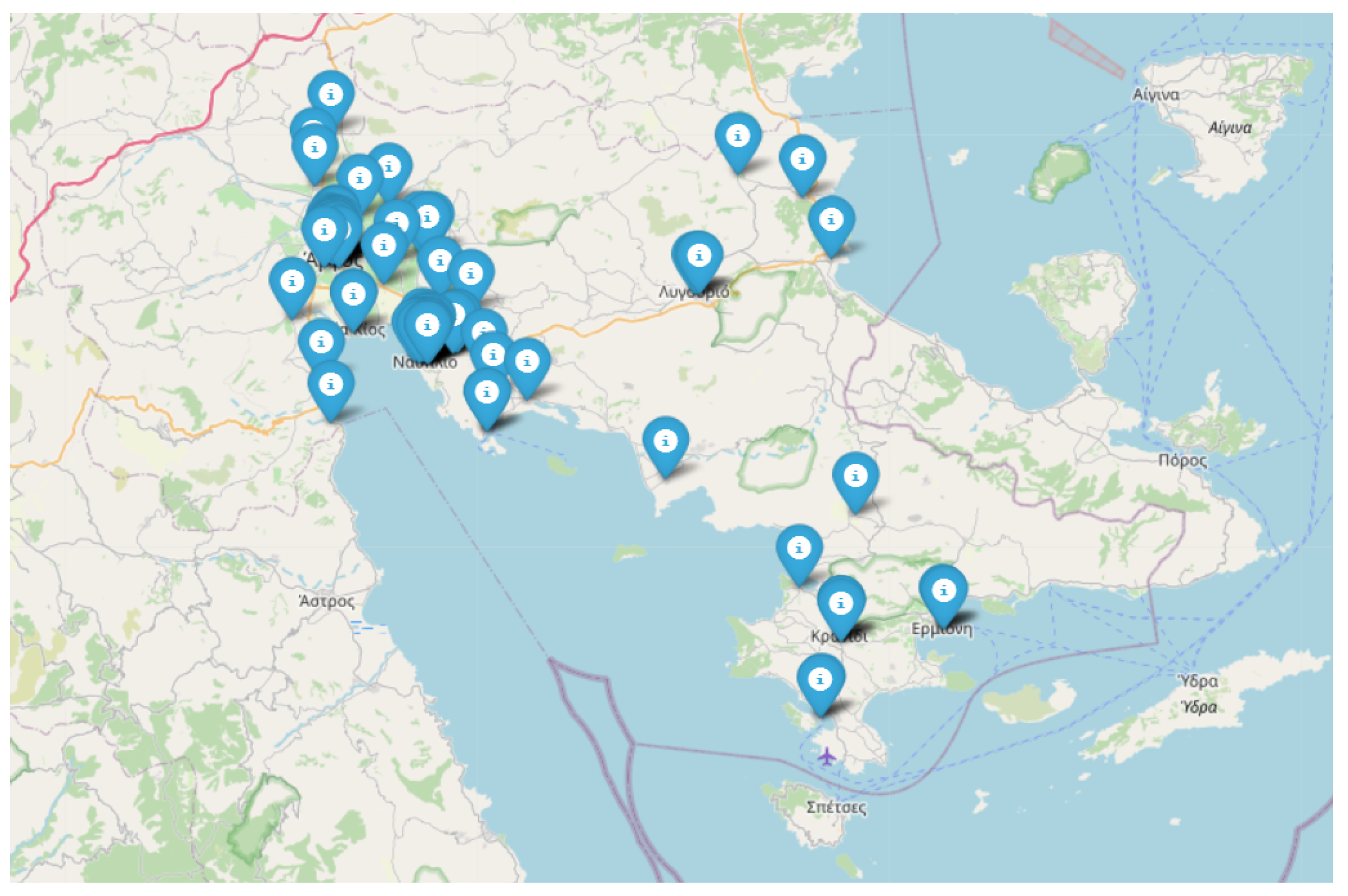

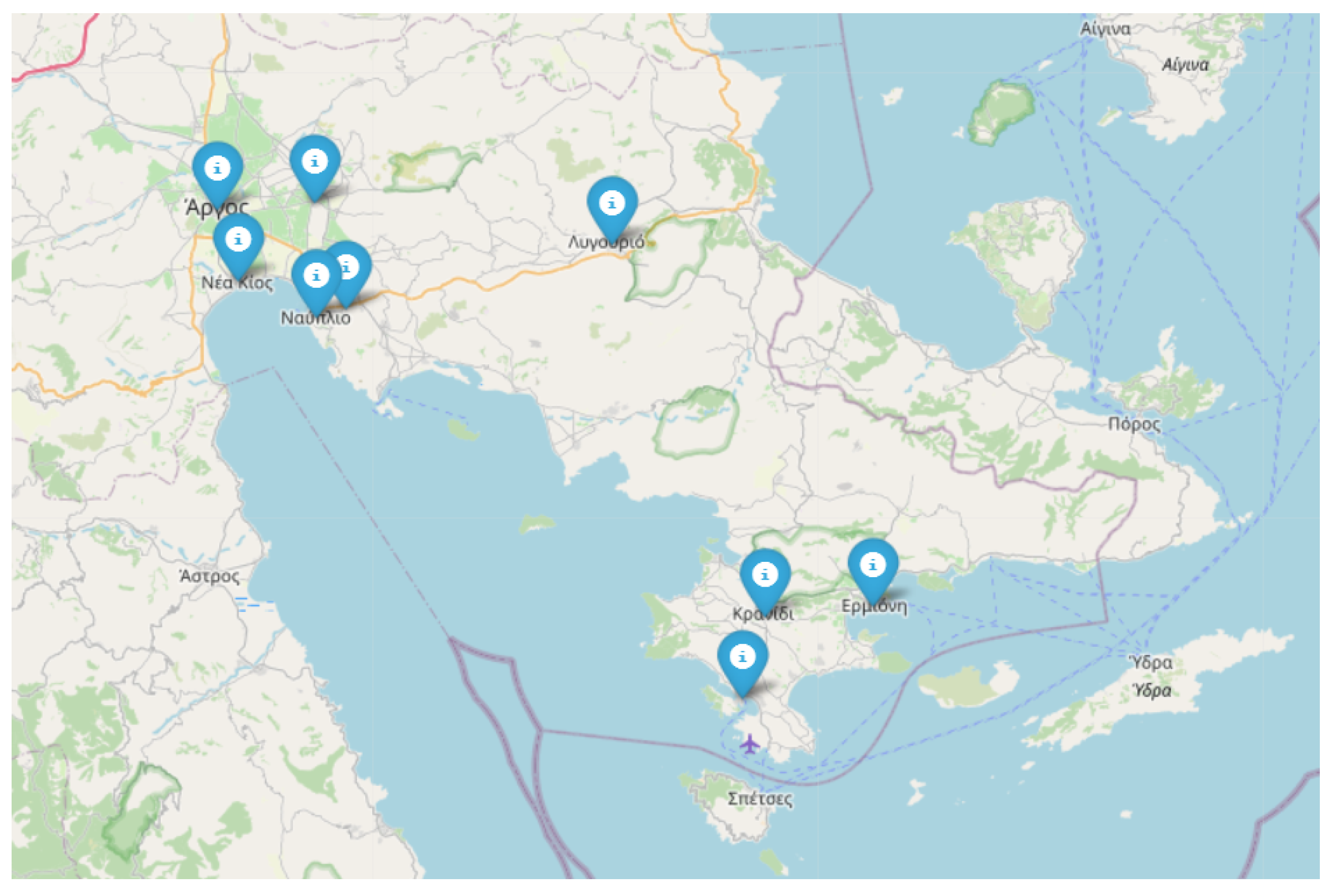

To overcome such weaknesses, in this work we propose the use of pharmacy stores to establish an extensive, reliable and coordinated network of AEDs. In order to assess the potential benefit of such an approach, we use as a case study the area of Argolis in the Peloponnese, home to around 90.000 people and extending over some 2.150 square kilometers (see

Figure 2). We evaluate the AED network from two perspectives:

immediate coverage, i.e. an AED readily available in the case of an incident and

partial coverage, i.e. an AED available at a reasonable distance.

We examine coverage with respect to population coverage, rather than geographic coverage, as ultimately what matters is the number of people that can potentially be saved, not the geographic area.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: In

Section 2.1 we present the information and data sources used in our calculations. Continuing, in

Section 2.2 we outline the key elements of our proposal and present the methodology of the study. Results are reported in

Section 3. In

Section 4 we discuss our findings while also discussing alternative scenaria, weaknesses of the work and areas for further examination. Finally,

Section 5 lists our concluding remarks.

4. Discussion

4.1. The 5 Scenaria

4.1.1. Ground Truth - Basis for Assessments

As a basis against which to compare our proposal we will use the existing network of state-controlled defibrillators, i.e. those located in the public hospitals and public medical centres. This is the data reported in

Table 1 as scenario A.

It should be noted that a smaller number of privately owned AEDs may be available at additional locations, but with their exact location and availability not clearly established and widely known, their utility in the case of an emergency is limited.

4.1.2. Augmented Public Network - Scenario B

It is almost inconceivable that nowadays one could enter a medical facility run by the government of a supposedly developed nation and find that no defibrillator is available. Especially at a time when defibrillators are starting to become available via private initiatives in all shorts of places - including stadiums, schools, restaurants, etc.

Specifically for the case of the region of Argolis that is considered in this work, the cost for the procurement of an AED for each of the regional medical offices that do not already have one would not exceed 12.000 euros in total. This would be a one-time expenditure and clearly it would not be a prohibitive cost; the current yearly cost of operation for these facilities is immensely higher.

At the same time, as seen in

Table 6 (which is compiled by combining findings from

Table 1 and

Table 2), this procurement would significantly augment the partial population coverage (from 28.34% to 41.68%. Much more importantly, it would more than triple the population coverage for immediate access to a defibrillator from from 3.14% to 12.03%, which is a more considerable increase.

Table 6.

Evaluation of a maximal public network of AEDs.

Table 6.

Evaluation of a maximal public network of AEDs.

| Coverage |

Existing |

Adding regional offices |

Augmented by |

| immediate |

2.827 (3.14%) |

10.837 (12.03)% |

8.010 (283%) |

| partial |

25.527 (28.34%) |

37.546 (41.68)% |

12.019 (47%) |

Moreover, this could begin to reinstate the public’s trust in the capabilities of the first line primary care offered by rural medical offices. Currently, public opinion / common knowledge is that regional medical offices are vastly understaffed, lack equipment and have no diagnostic capabilities. As a result they are only visited for administrative rather than medical issues - for example for repeat prescription of drugs - which is a huge waste of the resources that go into their operation. Including them in the defibrillator network and communicating this to the public could enhance public perception of rural medical offices, strengthen their in the community and augment the overall benefit they can bring to public health.

On the other hand, it should be underlined that not too much should be read into the results reported in

Table 2 and

Table 6, as if not considered in their proper context they could be misleading. More specifically, the findings assume that the AEDs in all the locations of public medical facilities are actually available to the public. But regional medical offices are very rarely open to the public, which means that the population coverage reported in these tables would rarely be practically achieved.

More importantly, it is exactly the fact that regional medical offices are not open at steady and widely known days and hours that makes them less suitable for the placement of AEDs. At a time of emergency one needs to be certain where to seek help, without having to worry whether the location will be open or closed.

4.1.3. Network of Pharmacies - Scenario C

The core proposal of this article is that pharmacies should be used to establish a wider network of defibrillators. This could be achieved by a law/directive, compelling every pharmacy store to acquire and maintain an AED and every pharmacist to undergo training on the identification of SCA and the use of the AED.

Pharmacies are in a prime position to add to a region’s capacities in emergency care. First of all, they are in a way already part of the primary care; in Greece it is quite common for citizens to visit the pharmacy, rather than the doctor, when facing either some minor medical issue that does not appear to warrant a visit to the doctor or a minor emergency in which the immediate feedback from the local pharmacist who is readily available might be more useful than the delayed expert opinion from a doctor with whom an appointment has to be made for a later time or day. Although this culture - of consulting a pharmacist for issues that clearly fall within a doctor’s expertise - is not ideal and should not be further promoted, in this case it could be useful; building on this existing practice it would be easier to effectively communicate to the public that when suspecting SCA they should visit their local pharmacy where they will find both a defibrillator and a pharmacist who is trained in its proper application.

An additional advantage of pharmacies is that their opening hours and locations are well known to everyone; and multiple apps exist that provide lists of available pharmacies together with driving/walking directions to the one that is closest.

More importantly, it is determined by law that some pharmacies are open and available at all times. The information regarding which is the pharmacy on duty that is closest to any given location is also available in numerous apps and website and the public is quite accustomed to using them.

All of the above mean that at a time of emergency such as a suspected SCA, no additional time will be lost while determining which is the optimal location to seek help. Any bystander can easily and immediately locate the closest pharmacy on duty and visit it, knowing that there they will get the urgent help they need.

An added advantage of the proposed approach is that although pharmacists are not doctors, their education and training falls largely within the medical domain. Clearly they are in a prime position to be trained in the proper use of defibrillators - if members of the general public can trained to use them, then certainly a pharmacist can be trained equally well if not much better. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that they will be better placed to perform an rough initial diagnosis in order to avoid application of a defibrillator when one is not required. Finally, being within a pharmacy has the additional benefit of having access to any kind of medication that may be additionally required in order to support and stabilise the patient until medics or paramedics arrive.

Regarding the evaluation of the actual population coverage that pharmacies would provide, in

Table 7 we combine findings from

Table 1 and

Table 3.

Table 7.

Evaluation of the proposed approach.

Table 7.

Evaluation of the proposed approach.

| Coverage |

Existing |

Proposed |

Augmented by |

| immediate |

2.827 (3.14%) |

23.323 (25.89%) |

20.496 (725)% |

| partial |

25.527 (28.34%) |

53.154 (59.01%) |

27.627 (108%) |

We observe that the implementation of the proposed approach, i.e. using pharmacies to establish a network of AEDs in the area of Argolis, would result in a more than eight-fold increase of the population that will have immediate access to defibrillator (from 3.14% to 25.89%), potentially leading to the salvation of numerous lives. The increase in partial coverage is also considerable, with the coverage more than doubling.

4.1.4. Adding Pharmacies to the Existing Situation - Scenario D

The establishment of a network of defibrillators via the pharmacies would not mean that the defibrillators of the general hospitals and the medical centres would cease to exist. Instead, the pharmacies would be added to the network of existing defibrillators and extend it.

As such, a reasonable scenario to examine is that of having a network of defibrillators that combines the pharmacies and the existing locations (two medical centres and two general hospitals). This scenario is evaluated in

Table 8, via a combination of information from

Table 1 and

Table 4.

Table 8.

Evaluation of the approach combining pharmacies with existing defibrillator locations.

Table 8.

Evaluation of the approach combining pharmacies with existing defibrillator locations.

| Coverage |

Existing |

Existing and pharmacies |

Augmented by |

| immediate |

2.827 (3.14%) |

23.385 (25.96%) |

20.558 (727%) |

| partial |

25.527 (28.34%) |

53.253 (59.12%) |

27.726 (109%) |

We immediately observe that the addition of the hospitals and medical centres to the network of pharmacies has little if any effect, as the evaluation for scenaria C and D is practically identical.

This indicates that, with respect to population coverage, the existing public network of defibrillators would have little to offer if the proposed network of AEDs in pharmacies were to be created. At least in its current form with only 4 locations in urban centres where numerous pharmacies are also located.

4.1.5. Maximal Network of Public Facilities and Pharmacies - Scenario E

One could argue that it is not ethical for the state to impose on private pharmacies the cost of acquiring and maintaining and the responsibility of operating an AED, at a time when the same obligations are not demanded from the state’s own medical facilities. Therefore, perhaps a more ethical and politically viable approach would be the combination of scenaria B an C, i.e. the placement of defibrillators in pharmacies as well as in all public medical facilities including the regional medical offices.

Table 9.

Evaluation of the approach combining pharmacies with all public medical facilities.

Table 9.

Evaluation of the approach combining pharmacies with all public medical facilities.

| Coverage |

Existing |

Pharmacies and all public medical facilities |

Augmented by |

| immediate |

2.827 (3.14%) |

25.456 (28.26%) |

20.558 (727%) |

| partial |

25.527 (28.34%) |

57.855 (64.23%) |

32.328 (127%) |

Since scenario E includes and combines all the locations of the previous scenaria, it was expected that it would achieve the largest population coverage of all the scenaria. On the other hand, the reservations discussed for scenario B regarding the suitability of regional offices as AED locations apply in this scenario too (the regional offices are rarely open and their opening times are neither steady nor widely known).

4.1.6. Comparison of the 5 Scenaria

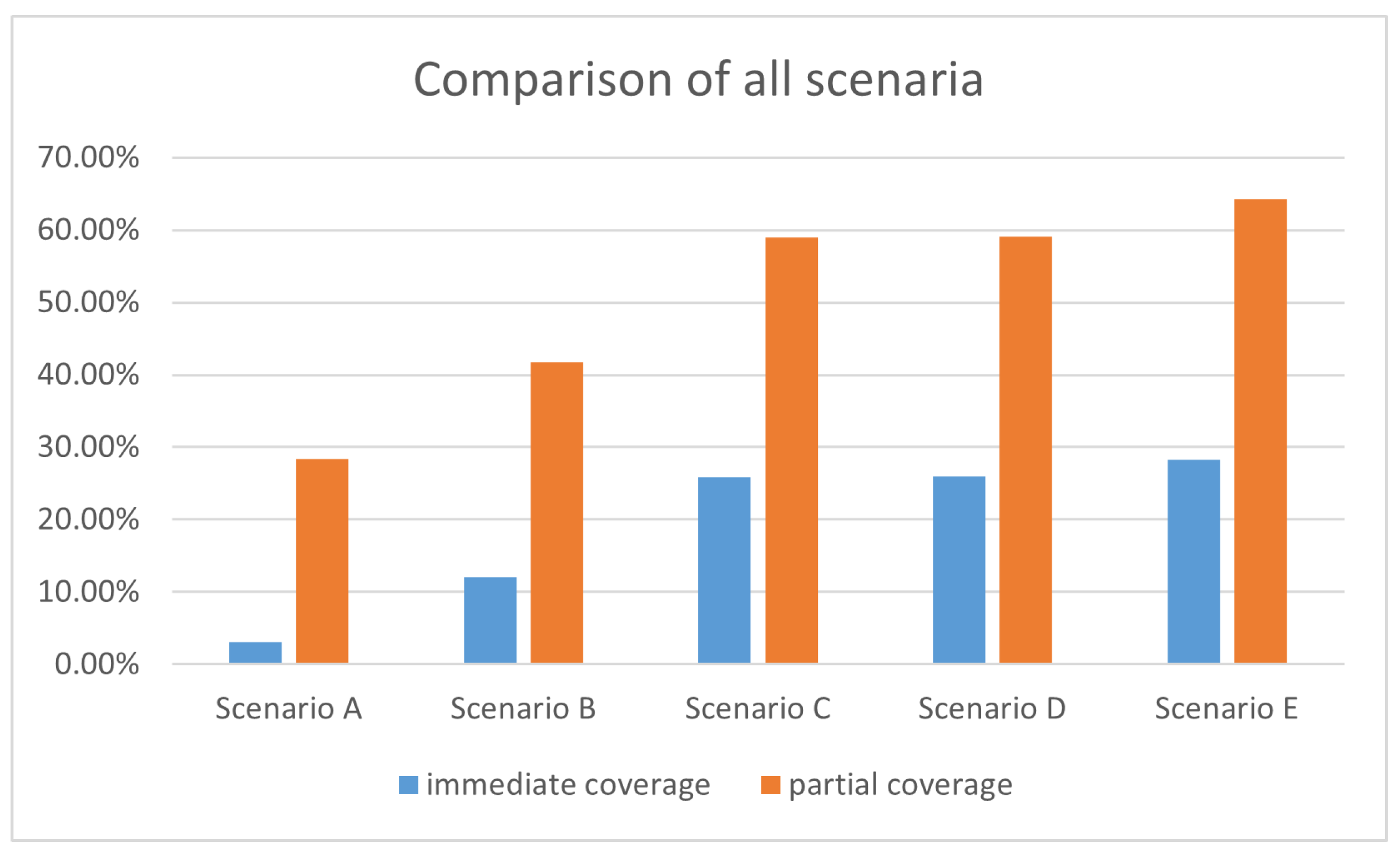

In

Figure 7 we summarize the evaluation of the five examined scenaria. As a reminder, the meanings of the scenaria are:

Scenario A: The current situation, with defibrillators only at the two general hospitals and the two medical centres.

Scenario B: The extended public network, with AEDs procured for each of the 16 regional medical offices.

Scenario C: The core proposal of this work, a network of AEDs comprising the region’s pharmacies.

Scenario D: Combination of scenaria A and C.

Scenario E: Combination of all the previous scenaria.

A first observation is that there is a monotonous enlargement of population coverage, both immediate and partial, as we move from one scenario to the next. The closest we get to scenario E, the more people that will be covered.

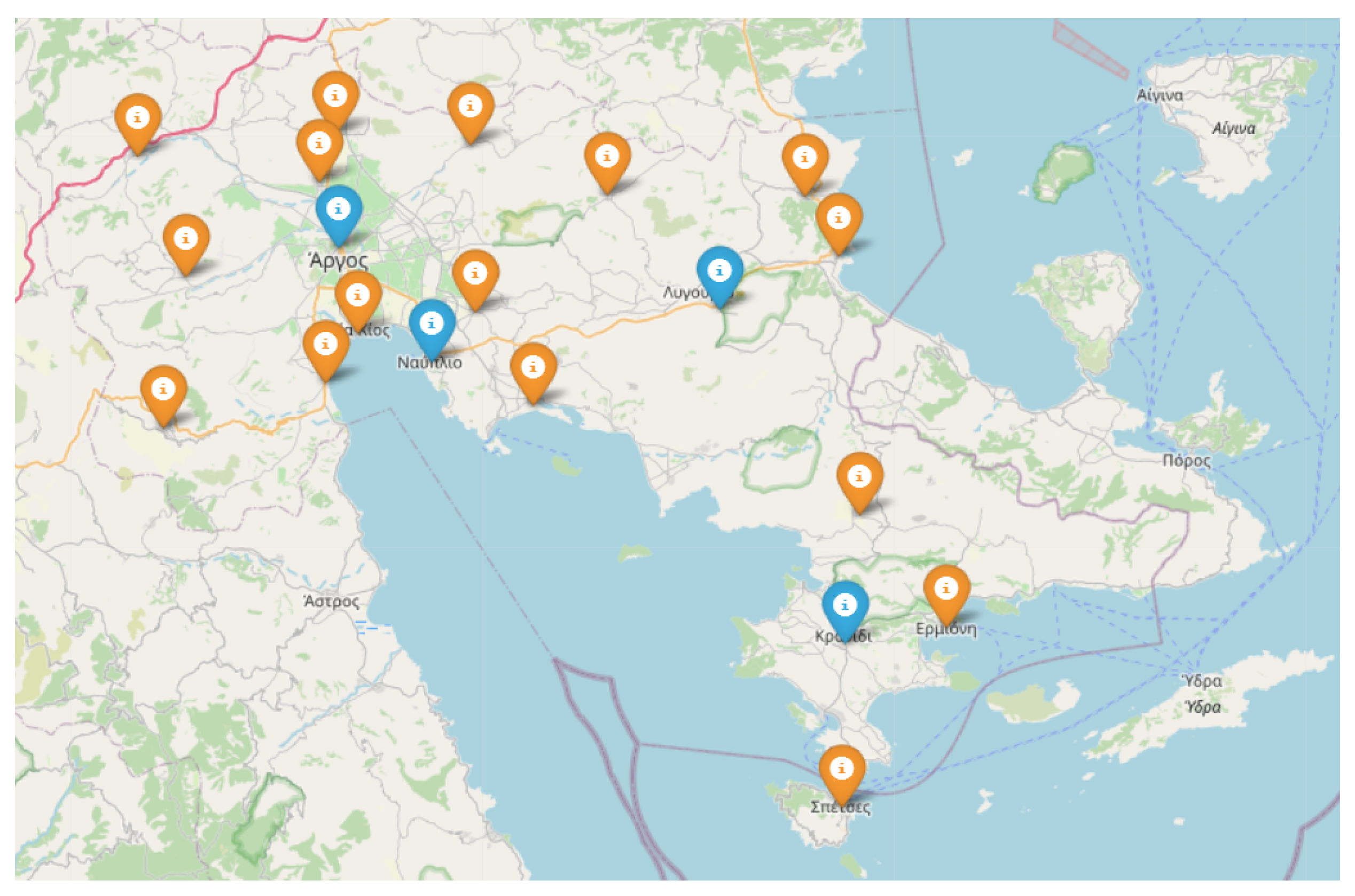

Another interesting observation is that although the network of public medical facilities of scenario B (see

Figure 4) seems to be better dispersed over the area of Argolis than the network of pharmacies (see

Figure 3), it is the network of pharmacies that provides immediate and partial coverage with AEDs to the most people. The reason is that whilst regional medical offices have been established with the intent to provide access to medical services to the most remote areas and thus follow a geographical distribution, pharmacies instead follow population density patterns. It is people, rather than space, that we aim to protect with AEDs and for this reason the network of pharmacies would be more effective despite not fully covering all the geographical areas of Argolis.

Examining the figure more carefully, we could split the scenaria in two groups: The scenaria with the lower population coverage (scenaria A and B with immediate coverage below 15% and partial coverage below 50%) and the scenaria with higher population coverage (scenaria C, D and E with immediate coverage around 25% and partial coverage around 60%).

The discriminating factor between the two groups is whether pharmacies are included in the defibrillator network. In other words, it is the inclusion of pharmacies in the network that makes the difference. The inclusion of public medical establishments does not hurt (especially if they are indeed in operation and available to the public), but in the end they make only a minor difference. All things considered, scenaria C, D and E can be viewed as different flavours of the same core scenario, that of having a network of pharmacies.

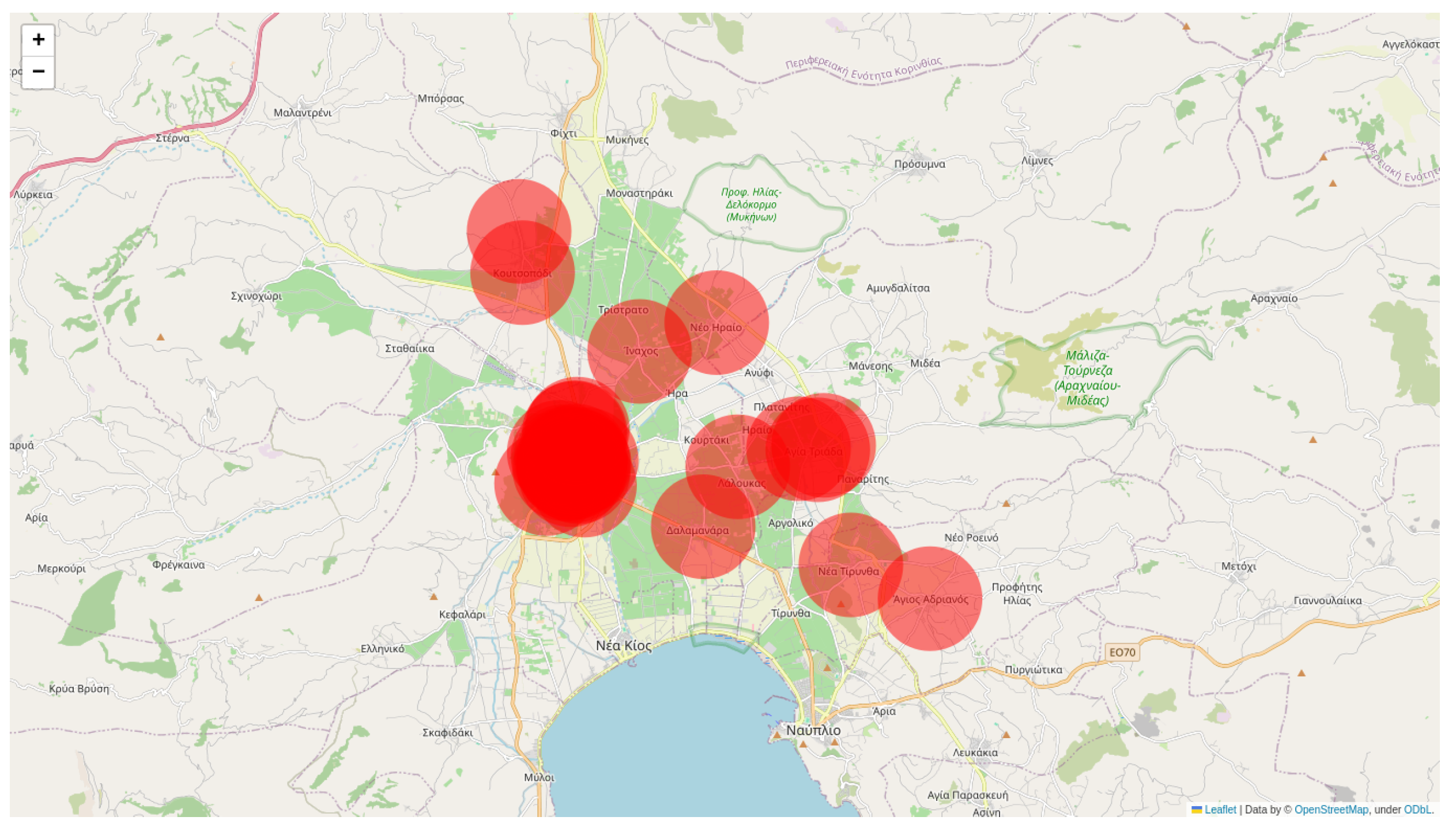

Considering the average rate of 9 incidents of suddern cardiac death per year, the region of Peloponnese has around 81 incidents of death due to SCA per year. Without detailed data regarding the specific incidents it is not possible to know more about their epidemiology.

But from a statistical point of view, if we assume that these incidents are distributed randomly in the region’s population, then using the calculations in this work we can estimate the number of incidents that could in theory be treated by an AED, should a random bystander be aware of why, when and how to intervene. These are summarized in

Table 10 and

Table 11.

Again we observe that the crucial intervention is that of using the pharmacies to establish a network of AEDs (scenario C), showing the potential to provide immediate access to 18 people per year who would otherwise loose their lives due to SCA and similarly partial access to 25 people per year who would otherwise loose their lives. The inclusion of the public medical facilities does extend the numbers of covered incidents, but only by a small amount.

4.2. Additional Benefits of Pharmacies as AED Locations

We have already mentioned that pharmacies have some important benefits as potential locations for the placement of AEDs. These include:

the fact that well known services exist that provide directions to the closest pharmacy,

the fact that pharmacists’ education makes them better candidates to be trained for and apply AEDs in the case of an emergence,

the fact that their locations follow population density patters and therefore provide good population coverage and

the fact that the local population already has a culture of visiting a pharmacy in the case of minor medical emergencies.

In addition to these, some more advantages can be identified:

A. Pharmacies are small establishments were guests are greeted immediately and urgent situations can be identified in a moment’s notice. In contrast, public establishments such as general hospitals tend to be larger and more bureaucratic. It is not rare for patients who visit the emergency room to have to wait for more than an hour before they are even assessed; in the case of a SCA incident that would of course be detrimental.

B. There is no time when a pharmacy is not available in some relatively reasonable distance. Whereas typically only one of the general hospitals remains on duty every evening, meaning that only those close to that specific hospital have immediate access to its services, there is always and at all times at least one pharmacy on duty in each sub-region of Argolis depicted in

Table 12 and pictured in

Figure 8.

4.3. Regarding the Need for Legislative Intervention

A defining aspect of our proposal is that ALL locations of a given type should hold a defibrillator. Knowing, for example, that all pharmacies have a defibrillator, in case of a suspected SCA a bystander can seek assistance at the closest pharmacy. If, instead, many, or even the vast majority of, pharmacies have defibrillators, then at a time of emergency one would have to wonder which pharmacy to head to when time is of the essence and there is a chance that upon arriving to the wrong pharmacy no help will be available.

This is exactly the problem with the current situation. Whilst defibrillators exist at a number of locations, the fact that one cannot know beforehand and with certainty where these locations are makes them much less useful at emergencies.

In order to address this, and for our proposal to have its maximum impact and effectiveness, it would be necessary to assure the public that an AED is always available at any pharmacy they might visit. The way to achieve this is via a legislative action, mandating that all pharmacies acquire and maintain an AED.

4.4. Regarding the Need for Subsidisation

Pharmacies are typically small stores operating on a small budget and with a controlled margin for profit. Moreover, in Greece they are hampered by the legislation that compels them to hand out medicines only receiving a small part of their cost whilst the remaining cost is given to them retrospectively by the state at a later date, often reduced and with delays. Therefore, pharmacists may be both unable and unwilling to undertake the additional cost of acquiring and maintaining an AED.

A program subsidising the procurement of the AEDs could help alleviate this barrier and facilitate the implementation of the proposed approach.

In addition to the initial procurement, there is a cost for their maintenance. Someone will need to be paid to periodically check that the equipment is up to standard, replace batteries and perform other repairs/updates as needed. Similarly, there is a cost and effort involved in maintaining people’s training up to date. Either with refresher courses for existing personnel or with new training for newcomers such as new employees of the pharmacies.

These activities also could and should be subsidised.

4.5. Alternative Scenaria

In addition to the purely medical facilities discussed herein, there are other public facilities that might be included in a public network of defibrillators.

Key among them are police stations and fire stations. The reason for this is that police persons and fire persons are (or should be) trained as first responders, as they are often the first to arrive at a location of an emergency. Police stations and fire stations are also prime locations for someone to seek help in an emergency. Moreover, their locations are well known to the public and they are always open, day and night.

Building further on this idea, all police cars and fire trucks could also be mandated to have an AED on board. Although the impact of this approach would be difficult to quantify (the real-time locations of police cars and firetrucks is not made publicly available for security reasons), it is clear that having an AED on each such vehicle would have a benefit.

Should, as suggested in the previous paragraph, vehicles be considered as locations for the placement of AEDs, then it would also make sense to consider public transport vehicles, such as buses and trams. Particularly in busy urban areas, there is almost always a means of public transport within reach. Therefore the implementation of such a scenario would make an AED immediately available in most cases.

Looking again towards the private sector, private medical practices, such as private clinics, could also be mandated to hold AEDs. These are locations that are already known to the public as medical establishments and also have personnel with appropriate medical training.

As a final scenario, large malls and supermarkets are places that are visited by large numbers of people. They could be mandated to have a defibrillator and at least one member of the staff properly trained present at all times. Whilst this solution still puts the economic burden on the private business, major supermarkets are financially larger than the typical pharmacy store by multiple orders of magnitude and can therefore absorb this cost much more easily. Similarly, many major supermarkets already have a member of the personnel always present at a supervisory / front desk role; assigning defibrillator duties to these members of the personnel would be quite straightforward.

Three added benefits of using malls and large supermarkets to establish a network of AEDs are that

their locations are well known to the public,

they have long opening hours and

their larger financial size which means that undertaking the cost of purchasing an AED is not as difficult as it would be for the much smaller pharmacies.

On the other hand, with this scenario the presence of staff with a core medical training is lost; in pharmacies, in addition to the training on the defibrillator the personnel comes with the additional multi-year studies on pharmacology which include a multitude of medical courses. These do not exist in a mall or in an supermarket.

On the other hand, focusing on the ethics of placing the burden on the private sector, it could be proposed that the school network could be used to extend the network of defibrillators, by training either all teachers or some in a more senior role such as the headmaster of each school. As the school system is the largest existing network of public facilities, this approach would guarantee maximum population coverage.

Drawbacks on this scenario, in addition to missing the presence of personnel with prior medical training, include the fewer opening hours as well as the multitude of days that the schools are closed. This is particularly emphasised during holiday periods when schools are closed for weeks or, in the case of summer, for months. It is also reasonable to expect an intense push back from teachers if they were forced to undertake this additional training, role and responsibility.

4.6. On the Existing Network of Privately Held AEDs

As has already been mentioned, there are a some defibrillators scattered in the region, primarily held by private citizens. Similarly to the UK, where “The Circuit”, the national defibrillator network, lists and maps the defibrillators across the country, the network of defibrillaltors in Greece is maintained by KidsSaveLives.

Unfortunately this service is not quite up to the standards of TheCircuit, for three main reasons:

1. It does not include all the defibrillators. More specifically, it only includes those listed by the individuals who have them. Thus, it is missing the most important ones: the ones available in hospitals and medical centres, which are also accompanied by the most appropriately trained medical professionals. As a result, in case of an emergency the KidsSaveLives service will not necessarily provide the best recommendation (if a hospital is within reach to the incident, it will obviously be best to go there rather than to a restaurant that also happens to be close by and has a defibrillator but no doctor to apply it properly).

2. The defibrillators listed in it are primarily held by private citizens. Thus their availability varies and follows the schedule of each individual holder. For example, when the defibrillator is in a restaurant (which is surprisingly quite common) it is only available during restaurant opening days and hours. As a result, in case of emergency it is not easy to locate the defibrillator that is the most easily accessible at that specific moment and for the specific location.

3. The service is neither well known, nor connected to the public health care service. Therefore, even if one where to call the Emergency Medical Services in case of a sudden cardiac arrest, they would not receive advice regarding the location of the closest defibrillator and would rather be advised to waste critical time waiting for an ambulance to arrive.

For these reasons, the existing network of AEDs is of course useful, but certainly not sufficient. An organised approach is required for the establishment and operation of a reliable and effective network; we have proposed such an approach in this work.

4.7. On the Availability Hours

The calculations in this work assume the availability of the AEDs in all the considered locations. The findings might be drastically different when considering the situation after hours or during holidays.

Whilst for opening hours the region has 2 hospitals, 2 medical centres, 16 regional medical offices and 90 pharmacies, during after hours and holidays there are reduced to:

1 hospital, in one of the two main cities, at a distance of more than 1 driving hour from some of the larger and densely populated areas of Argolis.

9 pharmacies, distributed in the region, reachable in at most some minutes from most populated areas.

3 police stations, distributed in the region, reachable in at most half an hour from any populated area.

2 fire stations, in the two main cities, at a distance of more than 1 driving hour from some areas of Argolis.

Although the population coverage of all scenaria would be greatly reduced, again it is the network of pharmacies that would provide the best coverage due to the number of on-duty pharmacies as well as to their distribution in the different areas of Argolis.

4.8. Weaknesses of This Work

There are a number of limitations and areas of weakness of this work. We discuss some of them in this section, aiming to provide the reader with the necessary context under which to consider our findings.

First of all, the definition of immediate and partial coverage is rather arbitrary. 300 and 1500 meters are reasonable distances, but geographic distance does not necessarily translate into time to travel.The type of roads, traffic, whether there is a straight line connection or not, whether one is on foot or using a vehicle and so on are all parameters that affect how the 3-5 minutes translate into geographical distance. This has not been considered in this work.

Secondly, the calculations of this work are based on the GHSL data which estimate population based on the presence of buildings, typically corresponding to people’s places of residence. But incidents may also happen away from the permanent residence, eg during an excursion in the mountains. Using the permanent residence locations to calculate percentage of population covered is not perfect.

Thirdly, the presence of an AED does not automatically mean that proper help will be provided in the case of an incident of SCA. Public awareness and ability to identify the need for defibrillation also matters. In this work we have not examined the degree of public awareness of how to maximise the training of the general public.

Fourthly, in this work we make no distinction between different types of presence of population. But in addition to the number of people present, the danger for an incident of a SCA is also affected by the activities of the people. For example the same number of people have a smaller chance of SCA when they are relaxing at home compared to when they are working out at the gym.

Despite these weaknesses, this being to the best of our knowledge the first work that quantifies the impact of a defibrillator network based on population data, we feel that its findings have value when interpreted correctly. For example, the above limitations do not put into question the usefulness of using the pharmacies in order to establish a more extensive, effective and reliable network of defibrillators.

4.9. Areas for Further/Future Examination

Areas for future research include

an examination of the effectiveness of the existing and proposed networks of defibrillators during off-hours when only on-duty facilities are available,

an assessment of the potential impact of impact of educating the public (for example what percentage of people might seek the defibrillator, and what percentage might use it correctly?),

the consideration of travel times instead of geometrical distances,

a more detailed analysis regarding the financial burdens of the implementation of the proposed scenaria and a study of ways to undertake them and

the estimation not just of the incidents with access to an AED but also of the actual number of lives saved and of the number of quality life years saved under the different scenaria, so that a cost-benefit assessment can be presented to the relevant authorities.

4.10. The Dissenting Opinion

There are of course two sides to this issue. Quicker access to proper medical care is undoubtedly beneficial in cases of emergency. But the argument can be made that making defibrillators accessible without the necessary presence of a trained medical professional may be associated to dangers that could outweigh the potential benefits.

It is generally accepted that the use of defibrillation involves dangers, even to the personnel using them as well as to bystanders due to the potential of inadvertent electric shock [

15]. There are even reports of injuries, in some very rare occasions serious ones, to the hospital personnel operating the devices [

16]. If even trained hospital personnel can be injured, it raises a question of what will happen to random members of the general public if they are given access and advice to use AEDs unsupervised and unassisted.

The dangers for the patient upon which the AED is applied are even greater [

17]. Discharging a defibrillator directly to a healthy person’s chest can be lethal, as has actually happened in at least one occasion [

18]. Therefore, perhaps giving free access to AEDs to random bystanders can put otherwise healthy individuals at risk, if the bystanders wrongfully assume defibrillation is needed.

Intented or malicious misuse cannot be ruled out either, as in at least one case a defibrillator was intentionally used succesfully to cause death [

19].

The dangers are not only limited to the immediate consequences. In the case of implantable cardiac defibrillators it has been shown that shocks promote myocardial stunning, heart failure, and pro-arrhythmic effects [

20].

For these reasons, broad access to and unsupervised use of AEDs by the general public may have adverse public health consequences, limiting and potentially outweighing the expected benefits. This danger is of course reduced when the AEDs and their application are under the supervision of trained healthcare professionals as is the case of pharmacists. But even in that case, it remains to be seen whether pharmacists will perform better than the general public, especially those pharmacists who have no desire on their own to have such a role and are only compelled via a legislative mandate.

5. Conclusions

Sudden Cardiac Arrest is a leading cause of death that it is characterized by the extremely narrow time window in which an intervention is necessary for the patient’s life to be saved. This small time window in most cases makes it impossible for proper medical assistance to arrive. But the intervention by random bystanders has proven to be greatly beneficial, in the cases where an Automated External Defibrillator was available. But the network of AEDs is limited and most importantly unreliable.

In this work we proposed taking legislative action to mandate that all pharmacies are equipped with an AED. Via analytical calculations based on the GHSL data and taking as a case study the area of Argolis in Greece we demonstrated that the implementation of the proposed approach would increase by more than eight-fold the number of people who have immediate access to a defibrillator, potentially saving many lives. It will also provide access to an AED within reasonable time to almost 60% of the population (in contrast to the current situation where less than 30% have such access). With respect to the number of incidents, this translates into providing immediate / partial access to a defibrillator to 18 / 24 incidents of SCA per year that would otherwise lead to death. Various scenaria were examined, with the data showing that in all cases it is mainly the inclusion of the pharmacies that augments the population coverage of the network of AEDs.

Other benefits of the proposed approach include the fact that pharmacists already have training in the broader medical field, there is always a pharmacy on-duty in every region and many applications provide in real time routing directions towards the closest pharmacy. On the other hand, the implementation of the proposal would impose on the pharmacies that is not high, but might be considered too much of a burden considering pharmacies’ typically small economic scale. A governmental subsidisation of AEDs might be warranted.

As a closing remark, it is a pity to loose lives and quality life years to SCA at a time when science and technology provide us with the tools to save them. Any government has a duty to its citizens to cultivate awareness, promote training and create the environment that can save these lives, including with the establishment and maintenance of an extensive and reliable network of AEDs.