1. Introduction

Clean air is one of the key issues of the European Union (EU) environmental policy. The goal is to achieve air quality levels that do not cause significant negative effects or threats to human health and the environment. One of the important air pollutants is ammonia (NH

3), which is mainly emitted from the agriculture sector. This sector is responsible for over 81% of global NH

3 emissions [

1]. According to data published by the National Center for Emissions Management (KOBIZE), in 2021 agriculture was responsible for 96% of national emissions of this gas. The largest share of emissions is related to the use of mineral and organic fertilizers, including natural fertilizers from farm animals (50%), and 46% of emissions are related to the manure management [

2]. Ammonia has a negative impact on the environment both locally and globally. The main threat is soil acidification resulting from the nitrification processes of ammonium ions coming from the atmosphere and eutrophication related to the supply of biogenic compounds to water, including NH

3 from agricultural sources [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Ammonia is also highly reactive in creating aerosols (PM2.5) that move over large areas [

7,

8,

9]. Moreover, this gas is easily transformed into other nitrogen compounds, therefore it may be involved in global warming, the destruction of the ozone layer, as well as the creation of photochemical smog [

10,

11,

12,

13].

One of the main documents regulating issues related to ammonia emissions is Directive (EU) 2016/2284 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2016 on the reduction of national emissions of certain atmospheric pollutants, called the NEC Directive, which sets out ammonia emission reduction targets for member countries from 2020 and 2030.

In the ammonia emission inventory, KOBIZE considers the impact of some activities limiting NH3 emissions, such as keeping pigs on partially slatted floors, covering storage of solid natural fertilizers, covering slurry tanks, 3-phase feeding of laying hens, or 4-phase feeding of fattening pigs. Quantitative determination of the scope of implementation of these techniques in practice was based on the synthesis of integrated databases of the Statistics Poland (GUS) and the National Research Institute of Animal Production. It was decided that it would be interesting to supplement these activities with research on the state of awareness of agricultural producers regarding the reduction of air pollutant emissions and the scope of their use of methods for reducing NH3 emissions.

The aim of the research was a preliminary assessment of the implementation status of methods for reducing NH3 emissions on farms and to learn the views and awareness of agricultural producers on reducing air pollutant emissions. Additionally, pilot studies will allow for testing the survey developed for this purpose.

2. Materials and Methods

Research on methods of reducing NH3 emissions on Polish farms and farmers' awareness of air pollutant emissions was carried out using a survey questionnaire that was made available to farmers in various ways. The surveys were collected in 2020-2021.

The subjective scope of the survey research included farms where animal production, plant production or plant-animal production were carried out. The survey consisted of two parts: the main part and the specifications. The main part of the survey consisted of two thematic sections: general questions regarding environmental protection, in particular reducing air pollutant emissions, and detailed questions regarding the methods used on farms to reduce ammonia emissions. Therefore, the scope of the research included the following information:

general information about farm owners,

general information about farms,

opinions and knowledge of agricultural producers regarding environmental protection,

knowledge of agricultural producers about ammonia emissions and related risks,

knowledge of agricultural producers about legal regulations regarding air protection and limiting air pollutant emissions,

activities undertaken on farms in nitrogen management,

methods used on farms to reduce ammonia emissions in the field of livestock housing systems,

methods used on farms to reduce ammonia emissions in the field of farm animal feeding systems,

methods used on farms to reduce ammonia emissions in the field of storage of natural fertilizers,

methods used on farms to reduce ammonia emissions during application of natural fertilizers to fields,

methods used on farms to reduce ammonia emissions during application of mineral nitrogen fertilizers to fields.

The main part of the survey on methods for reducing NH3 emissions was developed based on the National Advisory Code of Good Agricultural Practice for Reducing Ammonia Emissions [

14].

The results collected in the survey will be subjected to statistical analysis - χ2 independence tests. It is used to analyze two qualitative variables and determine whether there is a statistically significant relationship between them. The analysis will be carried out at the significance level of α=0.05. If the size of a given subgroup is limited, a correction for the chi-square independence test will be applied, the so-called continuity correction. Additionally, to improve the quality of statistical analysis, the number of groups will be limited (to three in selected categories):

farm area: 0-40 ha, 40-80 ha, over 80 ha,

education: vocational, secondary, higher.

The research will determine the impact of parameters such as farm area, age, animal species and education on:

application of nutritional reduction techniques,

time of incorporation the slurry,

time of incorporation the manure,

type of slurry application method used,

use of reduction methods during application of urea,

and what determines (age, education, farm area) the use of reduction techniques for groups of animals: cattle, pigs, poultry. Microsoft Excel was used to perform the statistical analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

The preliminary research was carried out on a group 30 agricultural producers from the Greater Poland Voivodeship.

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the respondents and their farms participating in the study.

3.1. General Knowledge of Environmental Protection

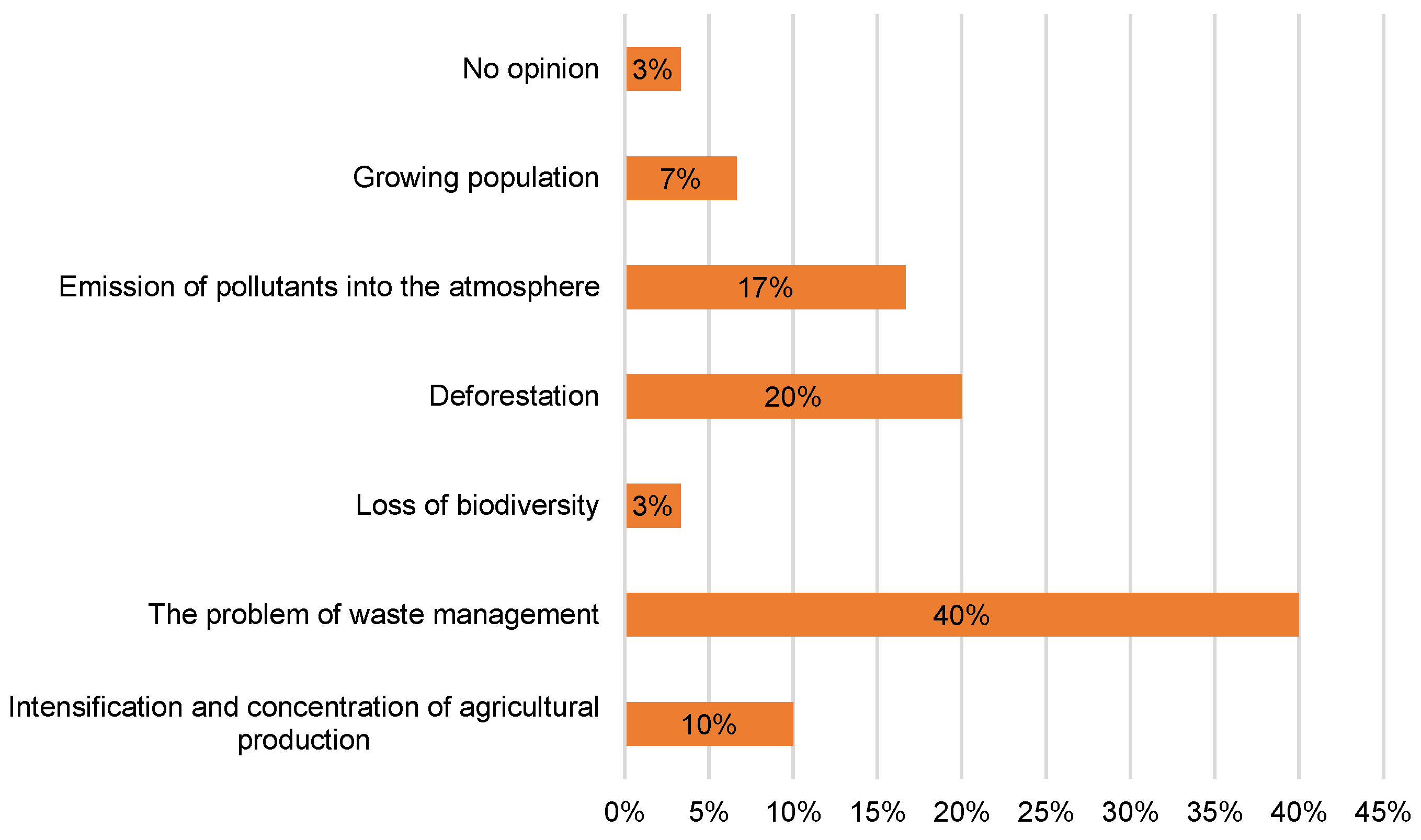

First, respondents were asked if they believed in their impact on the state of the environment. Most respondents (90%) stated that they had an influence, 3% believed that they had no influence, and 7% had no opinion on this matter. The results of research showed the greatest threats to the environment were the waste management (40% of respondents), deforestation (20% of respondents) and emissions of air pollutants into the atmosphere (17% of respondents) (

Figure 1).

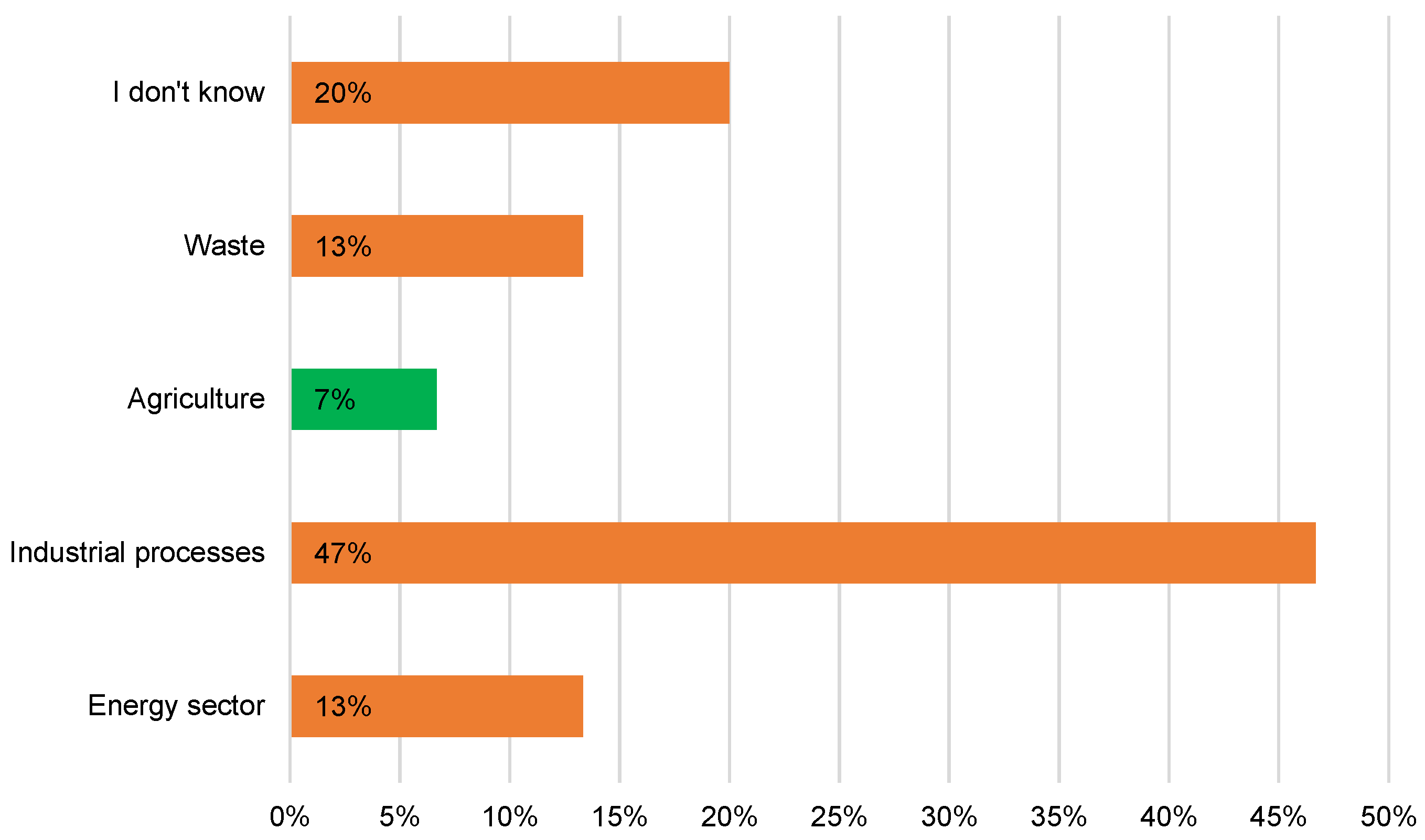

According to respondents, citizens (37% of responses) and state administration (37% of responses) are equally responsible for the state of the environment, followed by local government (13%) and industrial factories (7%). Respondents most frequently indicated raising ecological awareness (43%), followed by the creation of financial incentives (37%), controls and inevitable penalties (10%), and the use of local authorities (7%) as a way of improving the state of the environment. They stated that the industrial processes were the largest source of ammonia emissions into the air (47%). Only 7% study participants indicated agriculture (correct answer) as the largest source of ammonia emissions (

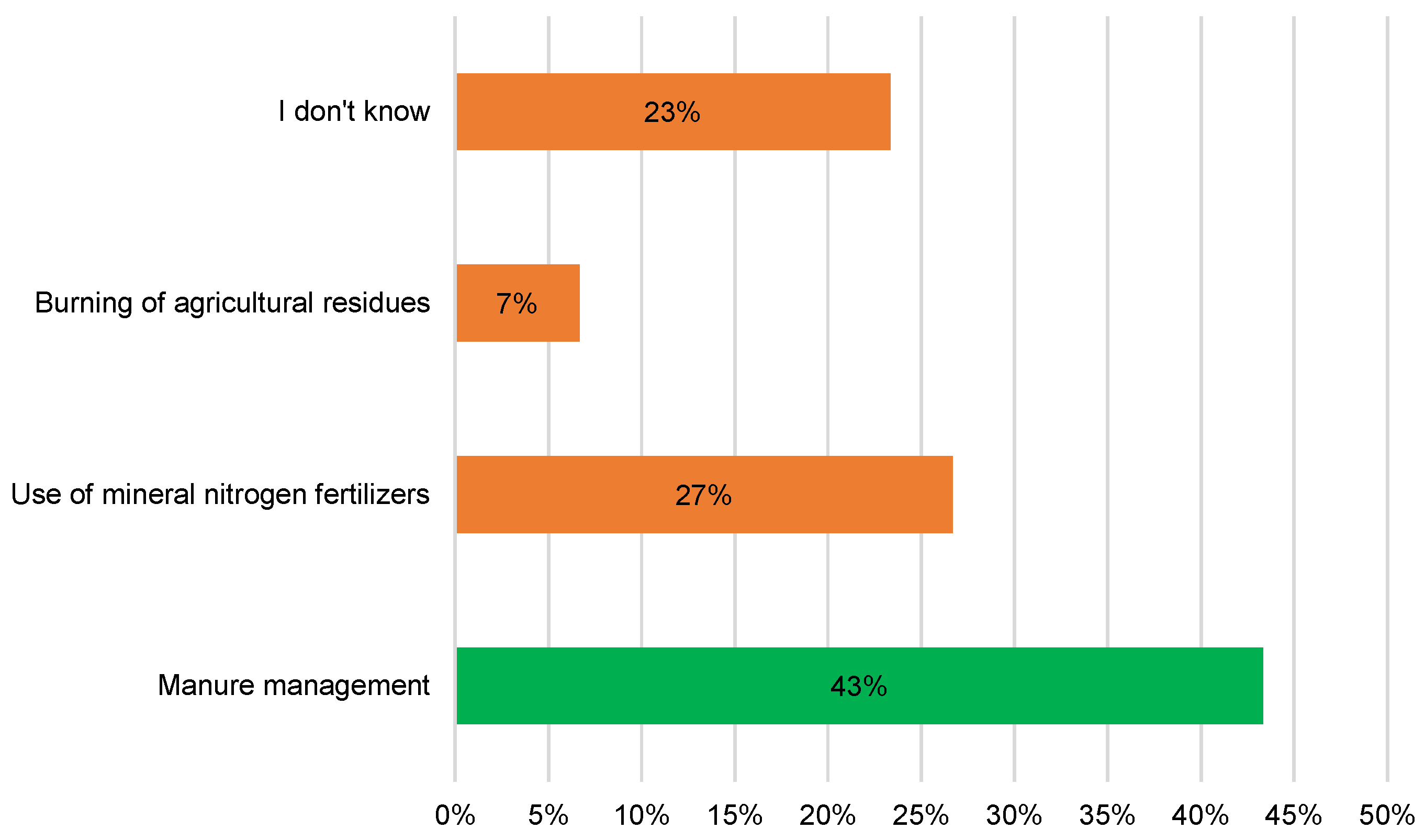

Figure 2). However, the largest source of ammonia emissions from agriculture was the use of natural fertilizers (43% of respondents), which is the correct answer. And then the use of mineral nitrogen fertilizers (27% of respondents), (

Figure 3).

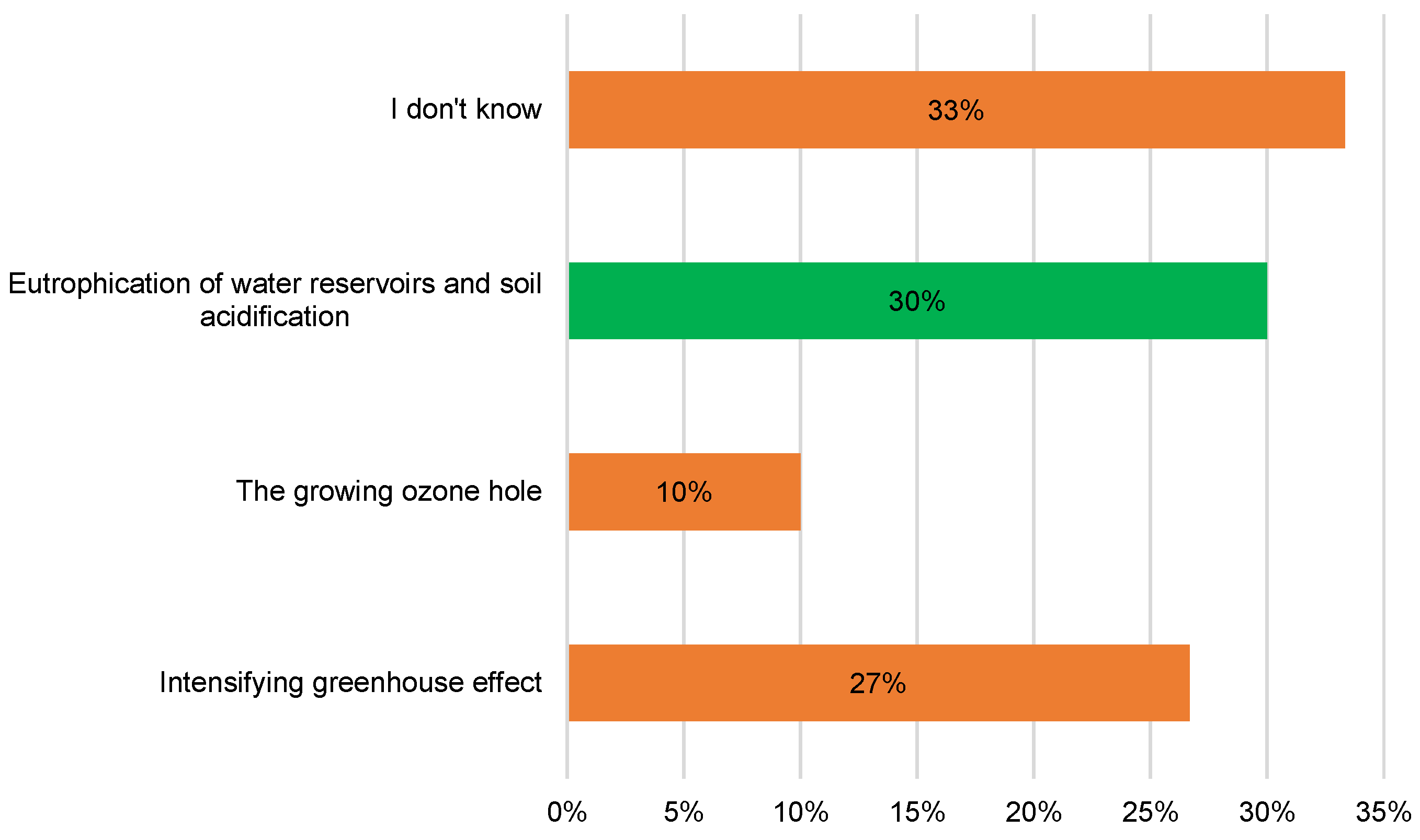

Only 30% of respondents correctly indicated that ammonia emissions mainly cause eutrophication of water reservoirs and soil acidification. 27% indicated the intensification of the greenhouse effect, and 33% of respondents marked the answer "I don't know" (

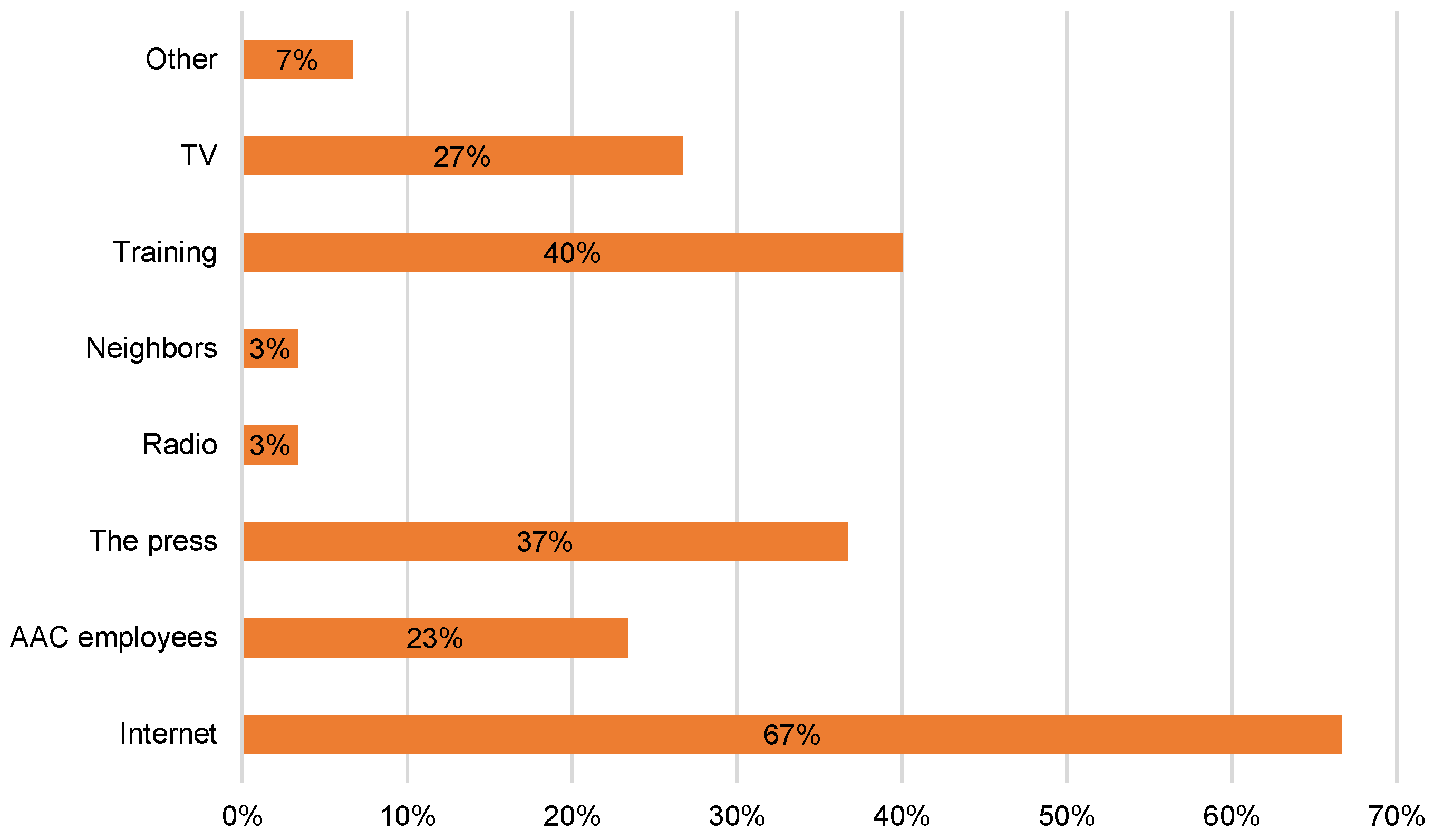

Figure 4). In the question regarding sources of information on environmental pollution, methods of reducing air pollutant emissions and legal regulations, a 3 information sources could be indicated. Respondents mainly chose: the Internet (67%), training (40%) and the press (37%), (

Figure 5).

3.2. Legal Regulations about Ammonia Emissions

The knowledge of applicable legal regulations regarding the reduction of ammonia emissions, the respondents' knowledge is varied. 93% of respondents had heard about the Nitrate Program, but only 33% have heard of the NEC directive.

The next part of questionnaire were the questions concerned knowledge of the applicable regulations regarding: maximum doses of manures used in agriculture, storage of manures and the dates when manures and mineral fertilizers can be applicated on each kind of agricultural lands. The most of respondents have limited knowledge in this area. Most respondents (70%) gave the correct answer to the question regarding the possibility of storing solid manure directly on arable land. Also, a significant percentage of respondents (57%) gave the correct answer to the question regarding the dates of application of solid manure on arable land. For the rest of questions, the percentage of correct answers was 40 (

Table 2).

3.3. Feeding Methods of Ammonia Reduction

The next series of questions were about ammonia reduction methods used on farms. The composition of animal feed directly affects emissions from animal excrements [

15]. One way to reduce NH

3 emissions is to reduce crude protein (CP) in the diet [

16,

17]. One study showed that a 2% reduction in dietary CP reduced NH

3 concentrations at 1 cm and 10 cm above the fecal surface by 49% and 24%, respectively, and it also reduced NH

3 emissions from the floor and the fattening house by 46% and 31%, respectively [

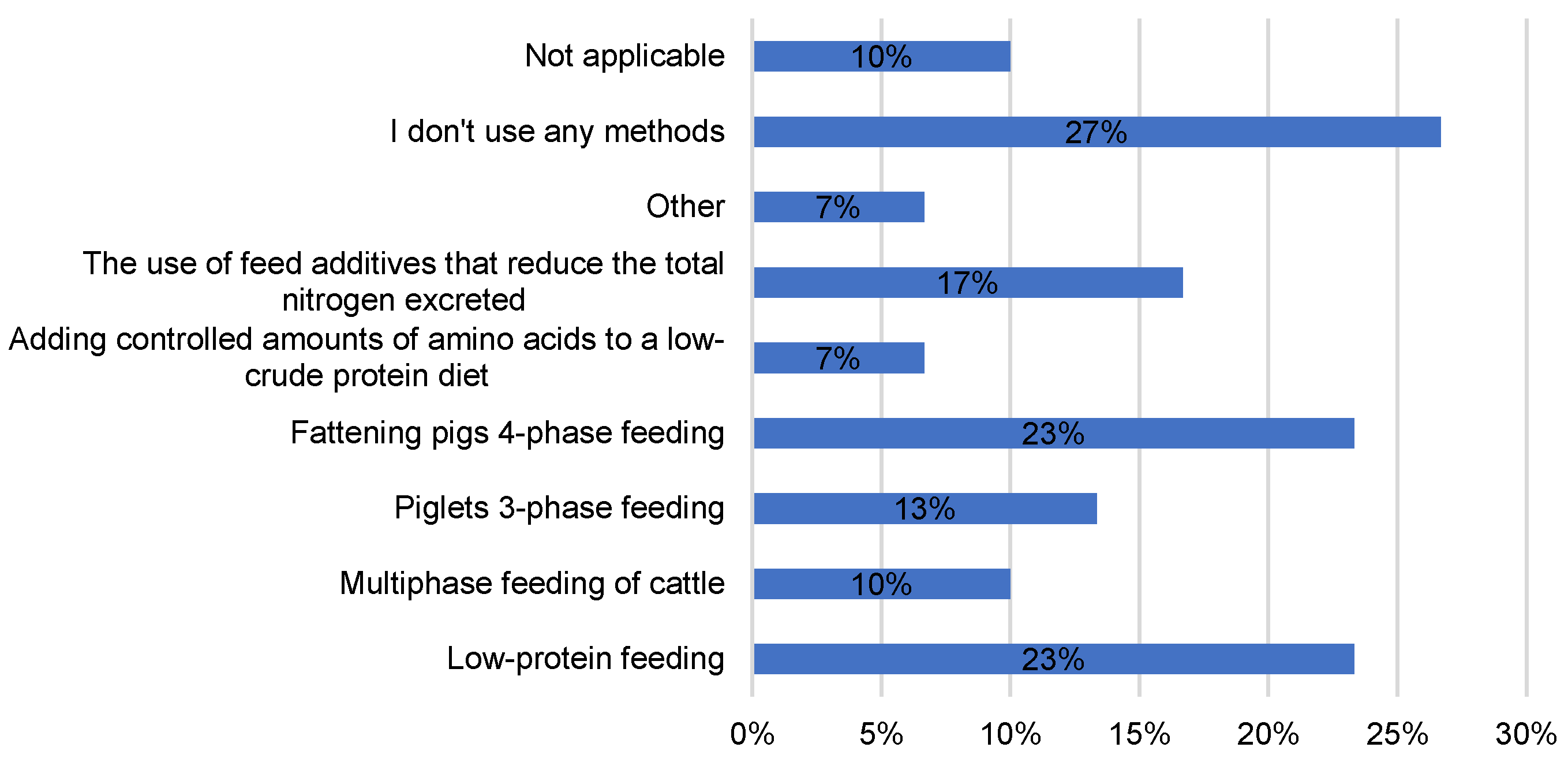

18]. The respondents showed that they used the following feeding ammonia reduction methods: low-protein feeding (23%), 4-phase feeding for fattening pigs (23%), the use of feed additives that reduce the total amount of nitrogen excreted (17%), 3-phase feeding for piglets (13 %), multiphase feeding of cattle (10%), adding controlled amounts of amino acids to low-crude protein diet (7%) and others - indicated by 7% of respondents. Respondents reported that they also used effective microorganisms. However, 27% of respondents also stated that they did not use any feeding methods (

Figure 6). Among the studied farms, only 4 of them used two nutritional methods to reduce NH

3 emissions, 1 farm used three methods, and 1 - six methods. Survey research on methods for reducing ammonia emissions in Polish agriculture was also conducted by other researcher. He asked respondents about: the use of nitrogen-fixing preparations in animal nutrition (7% of respondents answered yes, 83% - no, and 10% - I don't know among 520 studied farms) and about the use of appropriately selected feed additives ensuring the effective functioning of the animals' digestive tract (44% - yes, 51% - no, 5% - I don't know among the same research population) [

20]. According to KOBIZE, the most frequently used feeding methods were: 5-phase feeding of broilers (43.4% of the population), 3-phase feeding of laying hens (29.8%), 4-phase feeding of fattening pigs (25.1%) and protein feeding of dairy cattle (25%) [

2].

3.4. Animal Housing Methods of Ammonia Reduction

Animal housing is one of the stages at which ammonia emissions can be reduced. Some researchers identified and analyzed in detail several effective technologies and mitigation practices for each stage of manure management. Their results identified several promising approaches to reducing many gas emissions from the entire manure management process. Namely: removing excrement 2-3 times a week or daily when housing animals is an effective and simple way to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and air pollutants [

19].

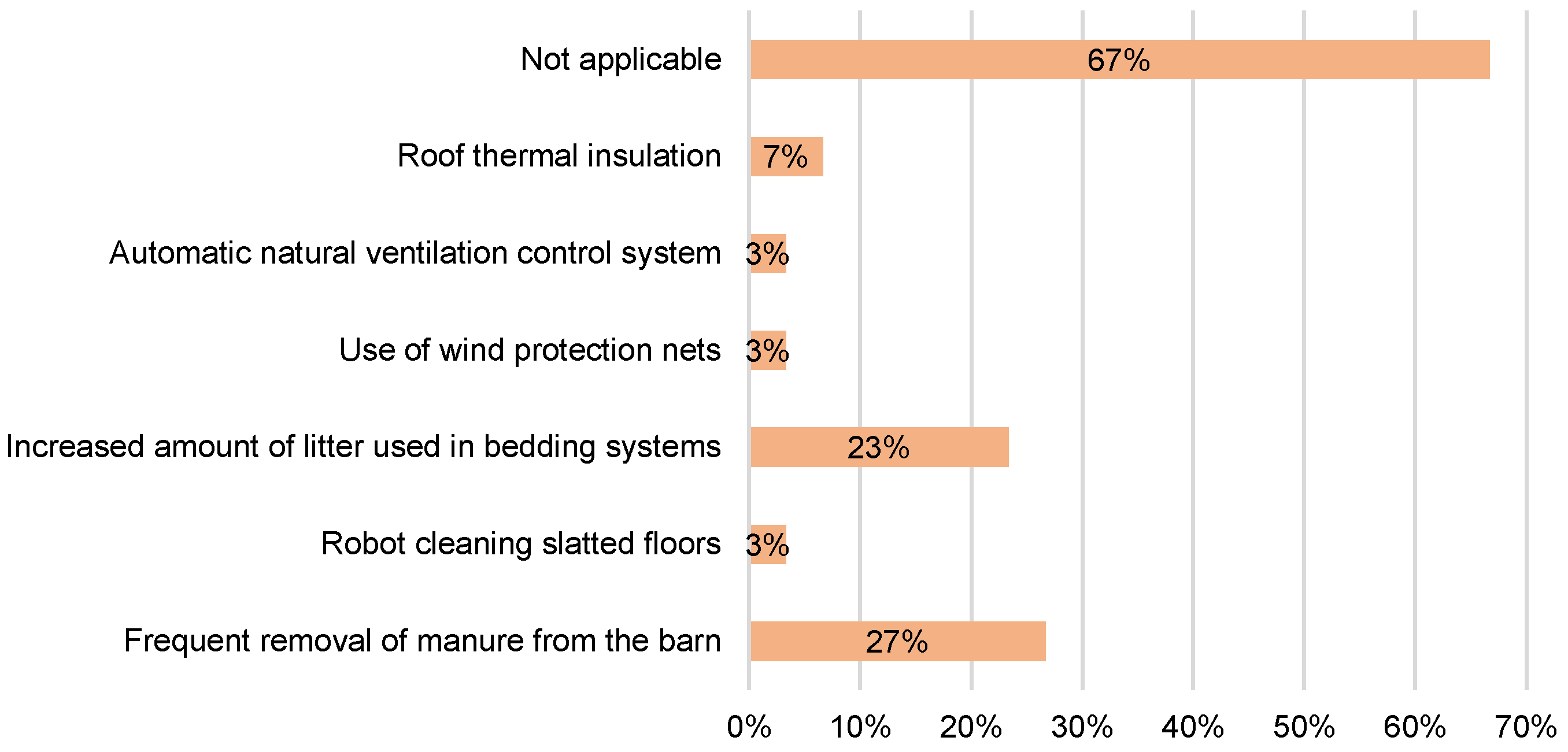

Among cattle housing the most used methods of reducing ammonia emissions were: frequent removal of manure from the barn (27%), increased amount of litter used in bedding systems (23%). The remaining methods were indicated by single people. However, 67% of respondents stated that this did not apply to them (

Figure 7).

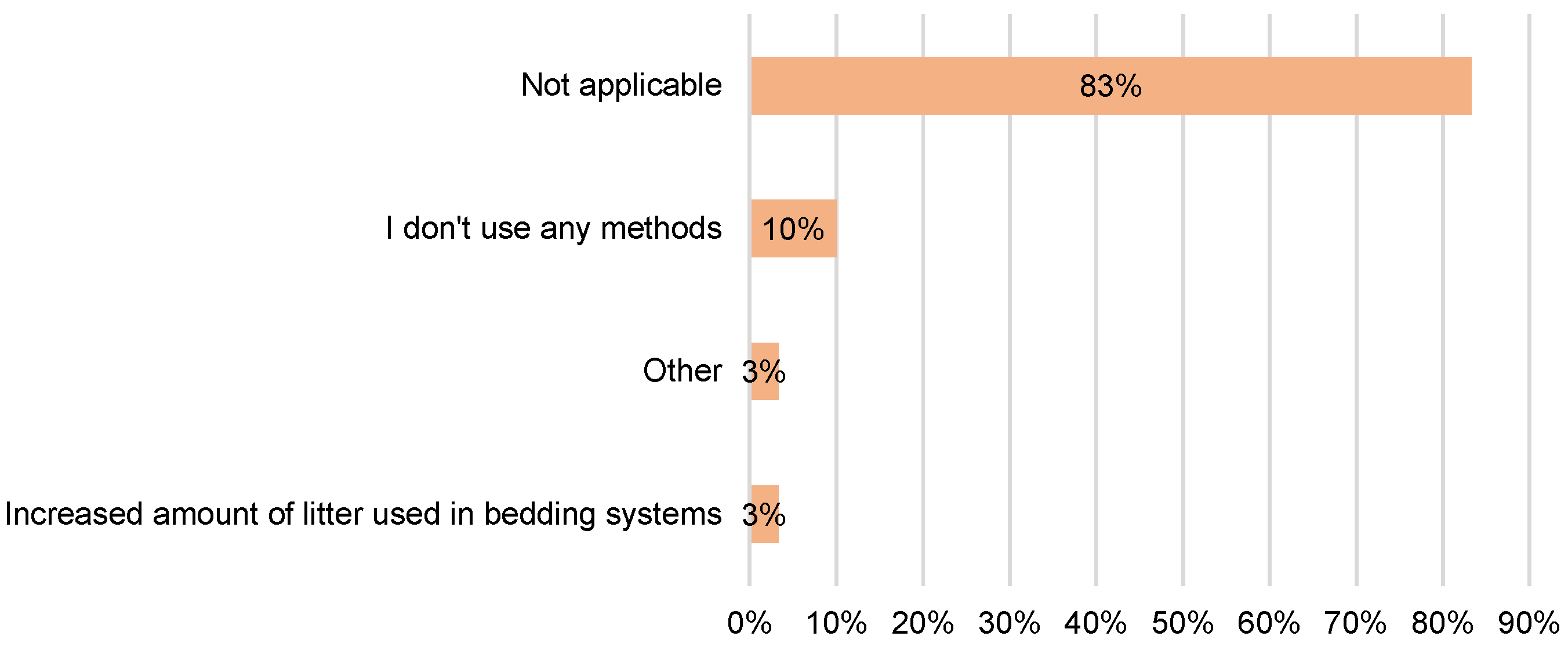

The 3 of 5 respondents producing poultry stated that they do not use any methods, one keeping ducks indicated that he uses an increased amount of litter and also one person indicated that he used other methods (

Figure 8).

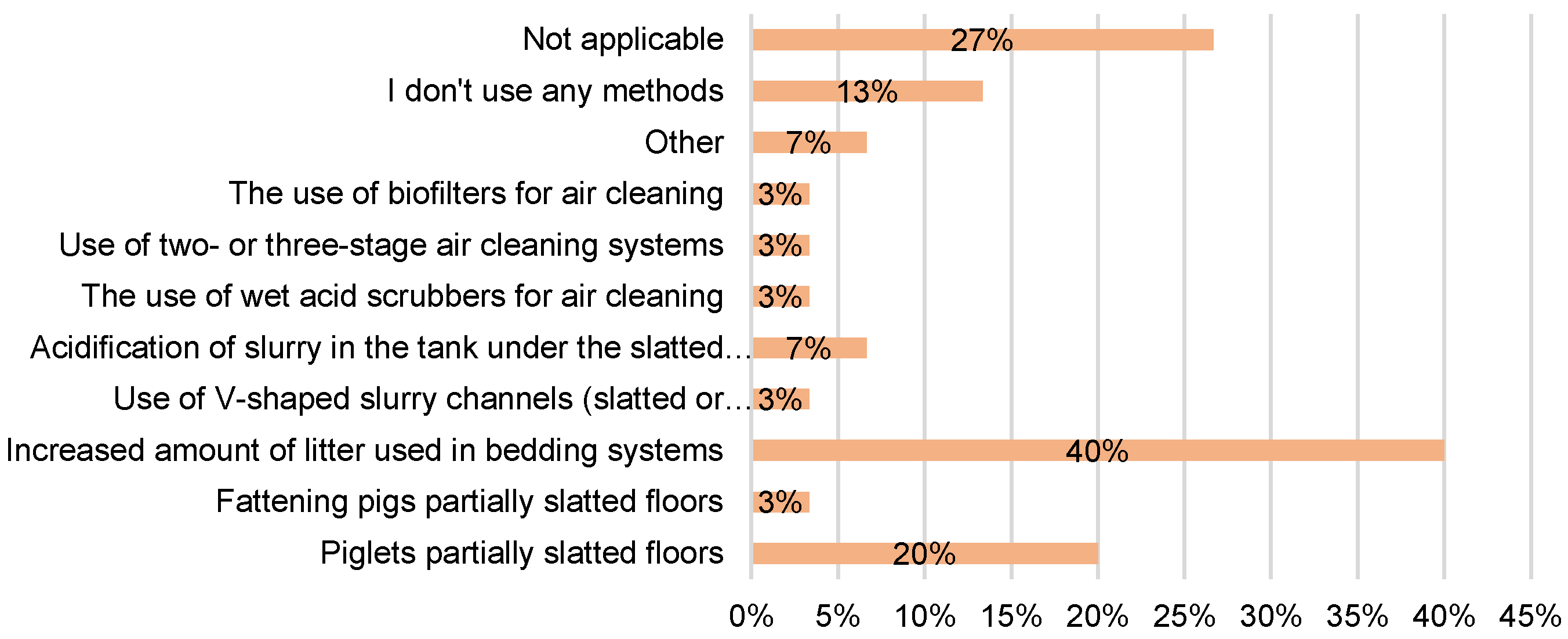

The studied pigs producers also used the methods of reducing ammonia emissions and they most often indicated: the use of increased amounts of litter in bedding systems (40%) and the use of partially slatted floors when housing piglets (20%). The remaining methods were used by single farm. However, three respondents indicated that they did not use any methods, and 27% of respondents indicated that this did not apply to them (

Figure 9).

Also in research [

20], not many of the 520 surveyed farms with animal production indicated the use of methods to reduce ammonia emissions while housing animals. The respondents using ammonia reduction methods applied the following techniques: microbiological and mineral-organic additives to animal faeces in livestock buildings (14%), underfloor heating (2.5%), mechanical ventilation with recirculation (34%), ultraviolet radiation (5%) and negative air ionization (2.5%). However, according to KOBIZE: the use of partially slatted floors on pigs farms covers 14.7% of the population, laying hens fast removal of solid manure covers 29.6% of the population, and laying hens solid manure ventilation covers 10.2% of the population [

2].

3.5. Low-Emission Manure Storage Systems

Storing manure is the next step in manure management where ammonia emissions can be reduced. One study identified and analyzed that acidification during slurry storage and treatment can reduce ammonia and methane emissions by 33-93% and 67-87%, respectively [

19]. In part of study concerning the storage of manures, the respondents stated that all studied farm had such the storage. 83% of them indicated that they had a manure plate, 90% had a slurry tank and 24 studied farms were equipped with both. However, among farms equipped with a slurry tank, the following types of cover were used: a rigid cover (67% of farms), floating plastic elements (3% of farms) and a natural crust on the surface of the slurry (3% of farms). 17% of farms do not cover the slurry tank. Farms that use slurry do not use flexible bags to store this natural fertilizer. The ammonia reduction methods use in managing of natural fertilizer excluding storage were also used and the following were indicated: acidification of slurry in a slurry storage tank (11% of farms), dilution of slurry (15% of farms) and separation of slurry (11% of farms). According to KOBIZE, a marginal percentage of the cattle, pigs and poultry population is covered by the solid manure covering technique, while 46.1% of the cattle population and 72.8% of the pig population are covered by the covering of slurry tanks [

2].

3.6. Low-Emission Manure and Urea Application Techniques

The final stage of manure management in which ammonia emissions can be reduced is its application to fields. According to the research [

19], shallow slurry injection is most effective in reducing ammonia emissions by 62–70%. One study investigated the reduction of NH

3 emissions using trailing hoses, trailing shoes, and shallow open slot injection, which were 30%, 50%, and 70% ammonia reduction, respectively [

21]. Similar results were obtained by [

22]. They showed that the use of trailing hoses, trailing shoes and shallow open-slot injection when applying cattle slurry reduced NH

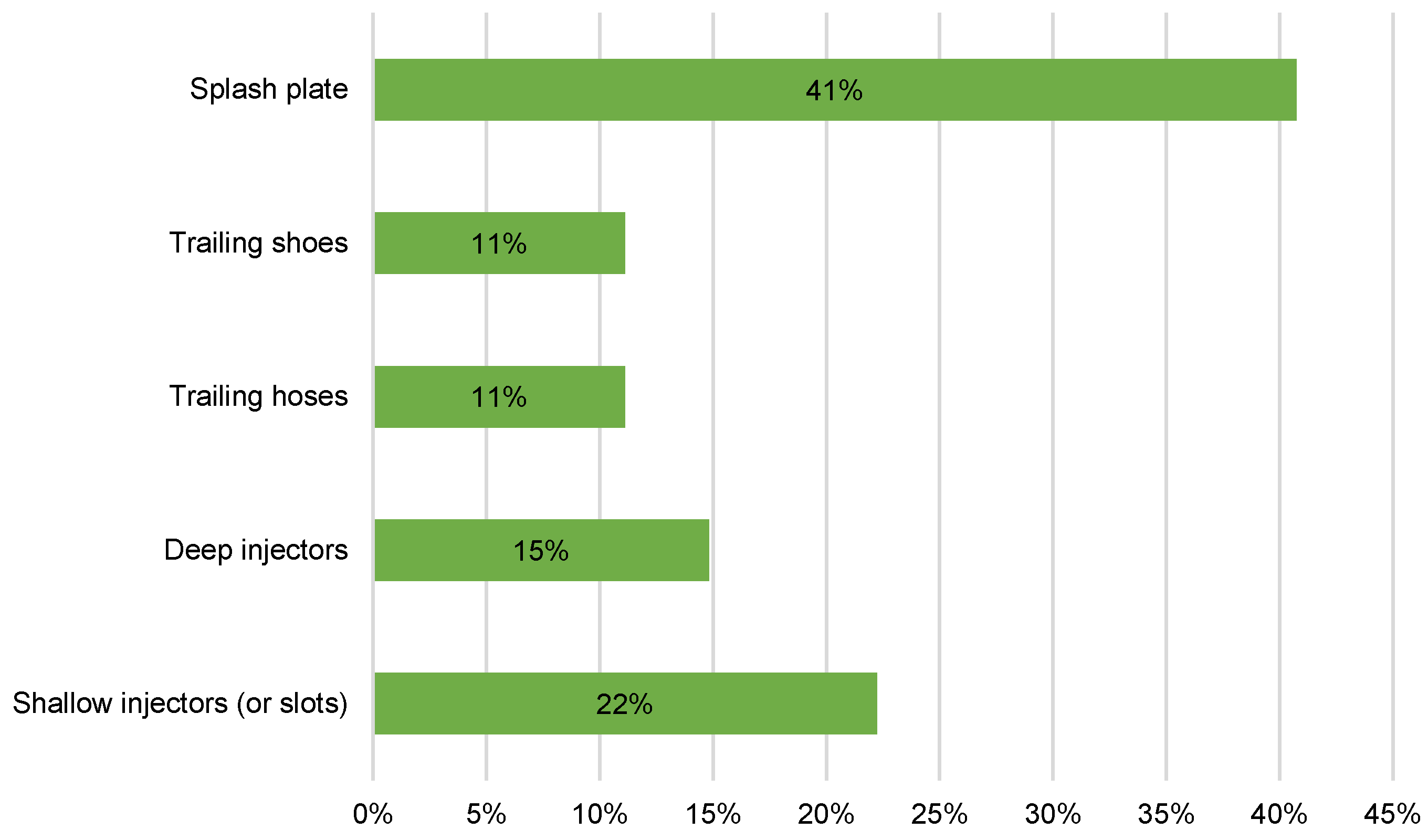

3 emissions by 35%, 46% and 62%, respectively, compared to surface application. Very positive results regarding environmental awareness were given by the part of study regarding the ammonia reduction methods during applying fertilizers to fields. Nitrogen fertilization plans are being developed in 87% of the surveyed farms. Moreover, 93% of respondents declare that choosing the date of application of fertilizers, they pay attention to the prevailing weather conditions, and 87% take into account the soil pH value when applying mineral nitrogen fertilizers. In terms of low-emission slurry application techniques, 41% of respondents use a splash plate, 22% use a slurry shallow (or slots) injectors, 15% use a deep injectors, and 11% of respondents use trailing hoses or trailing shoes (

Figure 10).

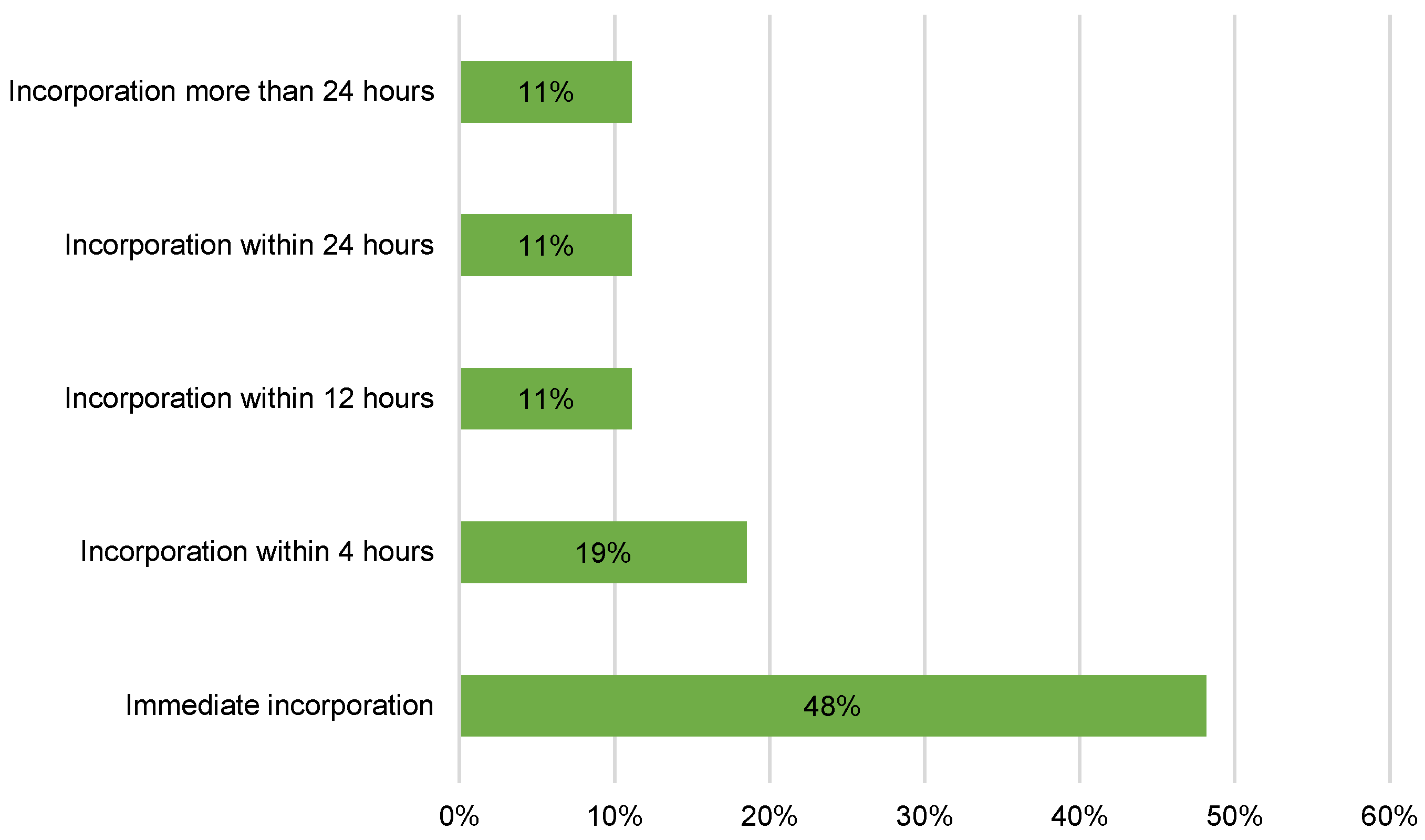

In part of the study concerning the time between slurry application and its cover with soil 48% of respondents indicated immediate incorporation, and 19% indicated incorporation within 4 hours of application (

Figure 11).

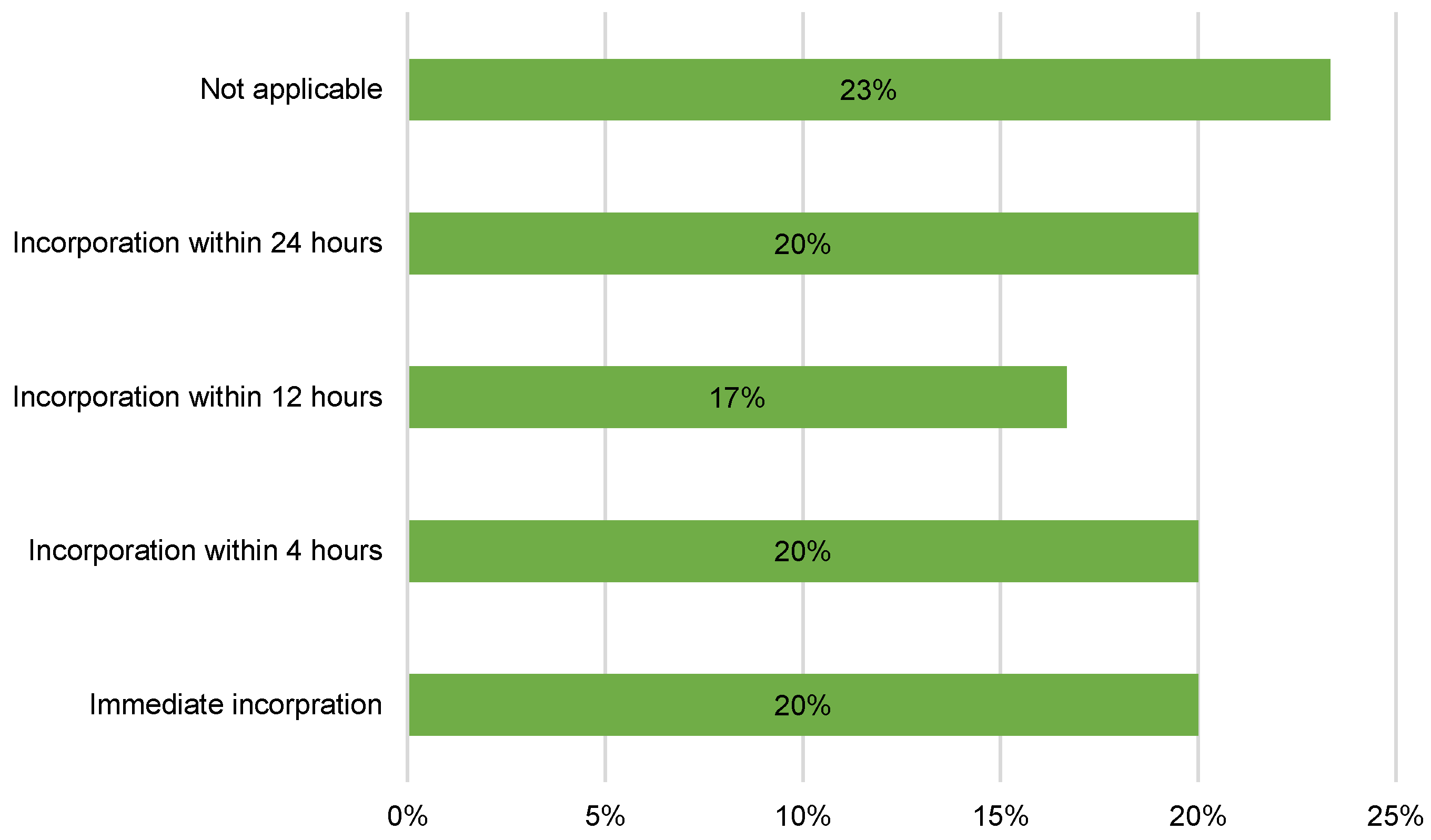

However, in relation to the time between solid manure field application and it is covered with soil the results were worse. 20% of respondents indicated immediate incorporation, the same number declared incorporation within 4 hours of application, and 17% of respondents indicated incorporation within 12 hours of application (

Figure 12).

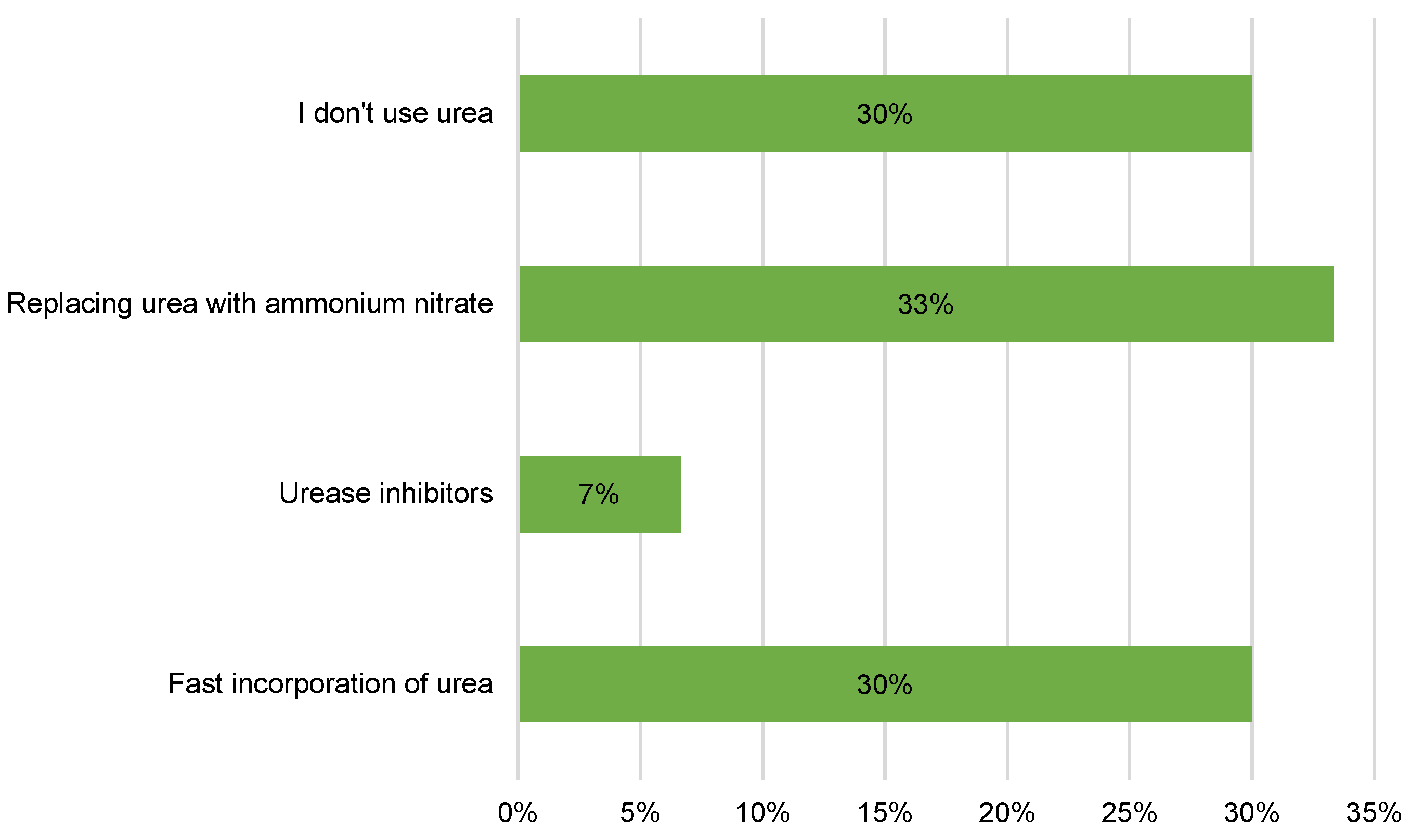

In turn, as the most popular methods of reducing ammonia during urea application, respondents indicated replacing urea with ammonium nitrate (33%), fast incorporation of urea (30%), not using urea (30%) and using urease inhibitors (7%). In turn, the most popular ammonia reduction methods used during applying urea in fields the respondents indicated replacing urea with ammonium nitrate (33%), fast incorporation of urea (30%), non-use of urea (30%), and use of urease inhibitors (7%), (

Figure 13).

The research about the use of reduction methods, among 1,034 farms with plant production in Poland also conducted other researcher [

20]. He showed that 75% of applying reduction methods use of divided doses of nitrogen fertilizers (depending on the plant vegetation period), 26% use of fertilizers with a slowed or controlled release of nutrients and 21% have a current nitrogen balance.

The results obtained in the pilot study were statistically analysed. In few cases the size of subgroups was less than 5 observations, which distorts the results of the analysis. Therefore, due to the limited size of studied population, statistically significant conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the relationships between the studied variables.

4. Conclusions

Based on the results of pilot surveys on the methods used to reduce NH3 emissions on Polish farms and farmers' awareness of air pollutant emissions, it can be concluded that farmers have general knowledge of environmental protection and generally agree that people have an impact on the state of the environment. According to respondents, improving the state of the environment is possible mainly by raising ecological awareness and creating financial incentives. Farmers do not identify the agriculture as the largest source of ammonia emissions is, but they know what is the largest source of ammonia emissions from agriculture. The knowledge of the respondents about the applicable legal regulations regarding the reduction of ammonia emissions, as well as the doses of manures used in agriculture, the possibility of storing manures and the dates during which natural and mineral fertilizers can be used on individual agricultural lands is often limited. Low-emission practices to reduce ammonia emissions from agricultural sources are not widely used. In the area of animal production, the use of modern ventilation and air cleaning systems is marginal. The most frequently recommended method is to use more litter in bedding systems. Similarly, feeding methods were not often used by farmers. The situation is much more favourable with regard to the storage of manure and the use of low-emission fertilizer application techniques.

Summarizing, it can be concluded that the survey is generally well designed and fulfils its purpose. Nevertheless, it requires corrections in some aspects, which will primarily aim to improve the readability and understandability of the questions for the respondent. Especially in a situation when the respondent fills out the survey questionnaire himself without the presence of the interviewer.

Currently, meeting the relatively high reduction target resulting from the NEC Directive may be difficult to achieve. Therefore, it is necessary to take decisive reduction actions in the area of agriculture. Some reduction activities are not obligatory, therefore it is difficult to determine the scope of application of these practices and determine the level of ammonia emission reduction. Therefore, this type of research monitoring the implementation of reduction methods is needed. Moreover, periodic research in this area will allow monitoring the activity of agricultural producers in implementing methods to reduce ammonia emissions. In the future, these data may be used during the air pollution inventory conducted by KOBIZE, as well as in reports on the implementation of the National Air Pollution Control Program.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.-B; Methodology, P.M.-B. and W.RZ.; Investigation, P.M.-B.; Formal analysis, P.M;-B. and W.RZ.; Writing—original draft preparation, P.M.-B. and W.RZ.; Writing—review and editing, P.M.-B. and W.RZ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wyer, K.E.; Kelleghan, D.B.; Blanes-Vidal, V.; Schauberger, G.; Curran, T.P. Curran Ammonia emissions from agriculture and their contribution to fine particulate matter: a review of implications for human health. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 323, 116285. [CrossRef]

- Bebkiewicz, K.; Boryń, E.; Chłopek, Z.; Doberska, A.; Kamola, E.; Kargulewicz, I.; Olecka, A.; Rutkowski, J.; Skośkiewicz, J.; Szczepański, K.; Walęzak, M.; Waśniewska, S.; Zakrzewska, D.; Zimakowska – Laskowska, M.; Żaczek, M. Poland’s Informative Inventory Report 2023. Submission under the UNECE Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution and Directive (EU) 2016/2284. Air pollutant emissions in Poland 1990–2021. National Centre for Emissions Management: Warsaw, Poland, 2023.

- Sommer, S.G.; Webb, J. and Hutchings, N.D. New Emission Factors for Calculation of Ammonia Volatilization From European Livestock Manure Management Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3:101. [CrossRef]

- Werner, M.; Kryza, M.; Geels, C.; Ellermann, T.; Ambelas Skjøth, C. Ammonia concentrations over Europe – application of the WRF-Chem model supported with dynamic emission. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26(3), pp. 1323–1341. [CrossRef]

- Yunnen, C.; Changshi, X. and Jinxia, N. Removal of Ammonia Nitrogen from Wastewater Using Modified Activated Sludge. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 25(1), pp. 419–425. [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.E.E.; Smyth, S.; Beattie, V.E.; McCracken, K.J.; McCormack, U.; Muns, R.; Gordon, F.J.; Bradford, R.; Reid, L.A.; Magowan, E. The Environmental Impact of Lowering Dietary Crude Protein in Finishing Pig Diets—The Effect on Ammonia, Odour and Slurry Production. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12016. [CrossRef]

- Baldini, C.; Borgonovo, F.; Gardoni, D.; Guarino, M. Comparison among NH3 and GHGs emissive patterns from different housing solutions of dairy farms. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 141, pp. 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gu, B.; Erisman, J.W.; Reis, S.; Fang, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X. PM2.5 pollution is substantially affected by ammonia emissions in China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, pp. 86–94. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-de-Santiago, D.E.; Ovejero, J.; Antúnez, M.; Bosch-Serra, A.D. Ammonia Volatilization from Pig Slurries in a Semiarid Agricultural Rainfed Area. Sustainability 2024, 16, 238. [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, M.; Tayà, C.; Burgos, L.; Morey, L.; Noguerol, J.; Provolo, G.; Cerrillo, M.; Bonmatí, A. Assessing Ammonia and Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Livestock Manure Storage: Comparison of Measurements with Dynamic and Static Chambers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15987. [CrossRef]

- Prosser, J.I.; Hink, L.; Gubry-Rangin, C.; Nicol, G.W. Nitrous oxide production by ammonia oxidizers: physiological diversity, niche differentiation and potential mitigation strategies. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26 (1), pp. 103–118. [CrossRef]

- Bougouin, A.; Leytem, A.; Dijkstra, J.; Dungan, R.S.; Kebreab, E. Nutritional and Environmental Effects on Ammonia Emissions from Dairy Cattle Housing: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, pp. 1123–1132. [CrossRef]

- Walczak, J.; Jarosz, Z.; Jugowar, J.L.; Krawczyk, W.; Mielcarek, P.; Skowrońska, M. Implementation of the NEC directive and BAT conclusions regarding the reduction of ammonia emissions from agriculture. Fundacja na rzecz Rozwoju Polskiego Rolnictwa, Wydawnictwo naukowe SCHOLAR: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available at: https://www.fdpa.org.pl/wdrazanie-dyrektywy-nec-oraz-konkluzji-bat-w-zakresie-redukcji-emisji-amoniaku-z-rolnictwa-1 (accessed on 15 March 2024). (in Polish).

- Jarosz, Z.; Faber, A.; Walczak, J.; Sowula-Skrzyńska, E.; Borecka, A.; Krawczyk, W.; Tyra, M.; Pieszka, M.; Knapik, J.; Połtowicz, K.; Karpowicz, A.; Kowalska, D.; Wrona, I.; Jugowar, J.L.; Mielcarek, P.; Rzeźnik, W.; Zieliński, M.; Sobierajewska, J.; Józwiak, W. Advisory Code of Good Agricultural Practice on the Reduction of Ammonia Emissions. Wydawnictwo ITP, Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/kodeks-dobrej-praktyki-rolniczej-w-zakresie-ograniczania-emisji-amoniaku (accessed on 15 March 2024). (in Polish).

- Sajeev, E.P.M.; Winiwarter, W. and Amon, B. Greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from different stages of liquid manure management chains: abatement options and emission interactions. J. Environ. Qual. 2018, 47(1), pp. 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Jha, R. and Berrocoso, J.F.D. Dietary fiber and protein fermentation in the intestine of swine and their interactive effects on gut health and on the environment: a review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 212, pp. 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Spiehs, M.J.; Whitney, M.H.; Shurson, G.C.; Nicolai, R.E.; Renteria Flores, J.A.; Parker, D.B. Odor and gas emissions and nutrient excretion from pigs fed diets containing dried distillers grains with solubles. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2012, 28(3), pp. 431–437. [CrossRef]

- Le Dinh, P.; van der Peet-Schwering, C.M.C.; Ogink, N.W.M.; Aarnink, A.J.A. Effect of diet composition on excreta composition and ammonia emissions from growing-finishing pigs. Animals 2022, 12(3), 229. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Ying, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, K. A review of mitigation technologies and management strategies for greenhouse gas and air pollutant emissions in livestock production. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 352, 120028. [CrossRef]

- Piwowar, A. Farming Practices for Reducing Ammonia Emissions in Polish Agriculture. Atmosphere 2020, 11(12): 1353. [CrossRef]

- Hafner, S.D.; Pacholski, A.; Bittman, S.; Burchill, W.; Bussink, W.; Chantigny, M.; Carozzi, M.; Génermont, S.; Häni, C.; Hansen, M.N.; Huijsmans, J.; Hunt, D.; Kupper, T.; Lanigan, G.; Loubet, B.; Misselbrook, T.; Meisinger, J.J.; Neftel, A.; Nyord, T.; Pedersen, S.V.; Sintermann, J.; Thompson, R.B.; Vermeulen, B.; Vestergaard, A.V.; Polina Voylokov, P.; Williams, J.R.; Sommer, S.G. The ALFAM2 database on ammonia emission from field-applied manure: Description and illustrative analysis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 258, pp. 66–79. [CrossRef]

- van der Weerden, T.J.; Noble, A.; de Klein, C.A.M.; Hutchings, N.; Thorman, R.E.; Alfaro, M.A.; Amon, B.; Beltran, I.; Grace, P.; Hassouna, M.; Krol, D.J.; Leytem, A.B.; Salazar, F.; Velthof, G.L. Ammonia and nitrous oxide emission factors for excreta deposited by livestock and land-applied manure. J. Environ. Qual. 2021, 50, pp. 1005–1023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).