Submitted:

02 July 2024

Posted:

03 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Particle Swarm Optimisation

2.2. Eavesdropping Behaviour in Animals

2.3. Altruism

3. Materials and Methods

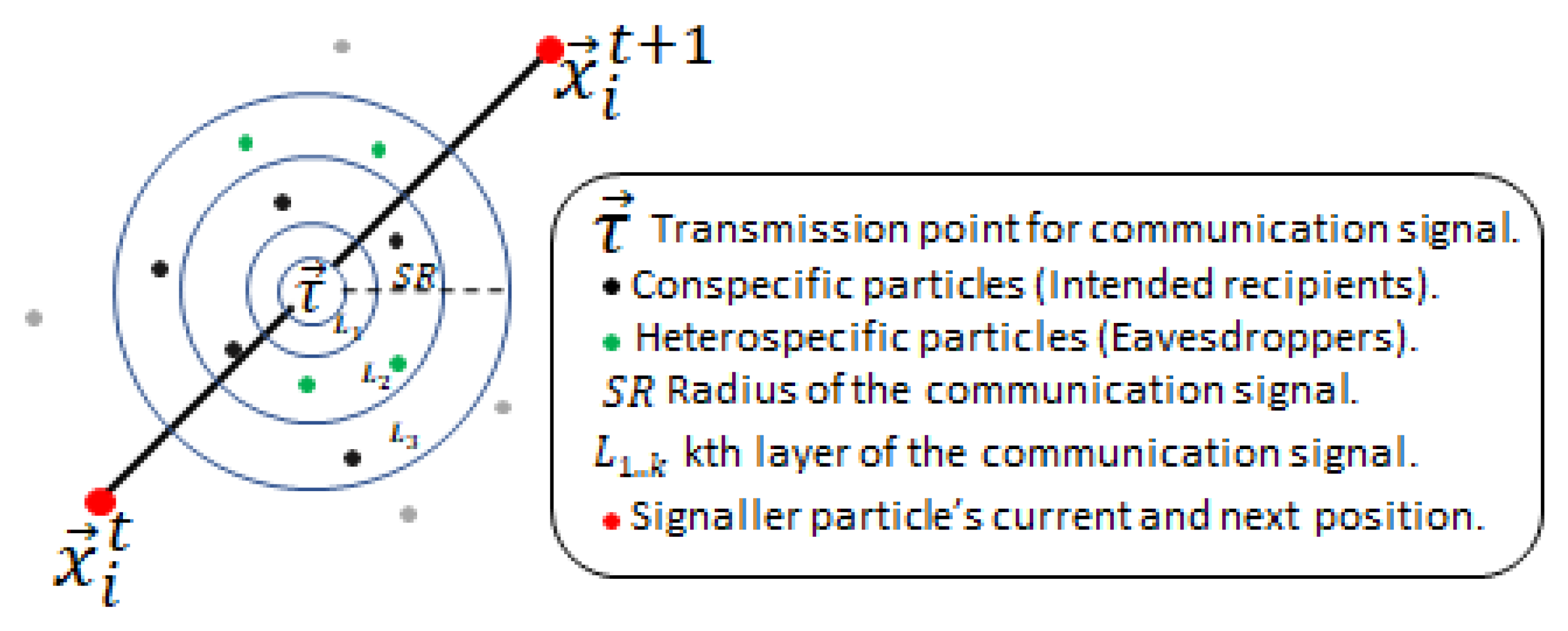

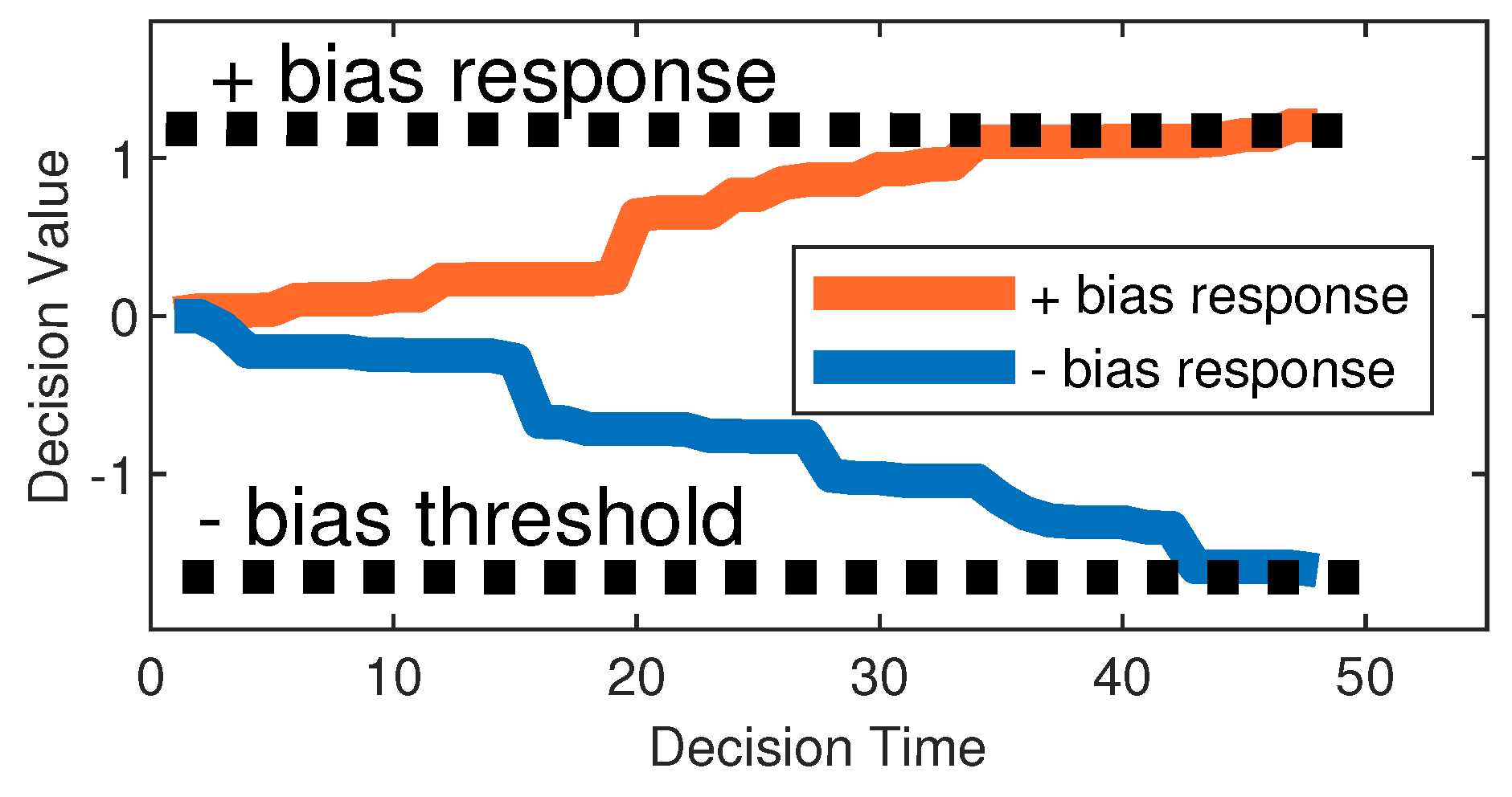

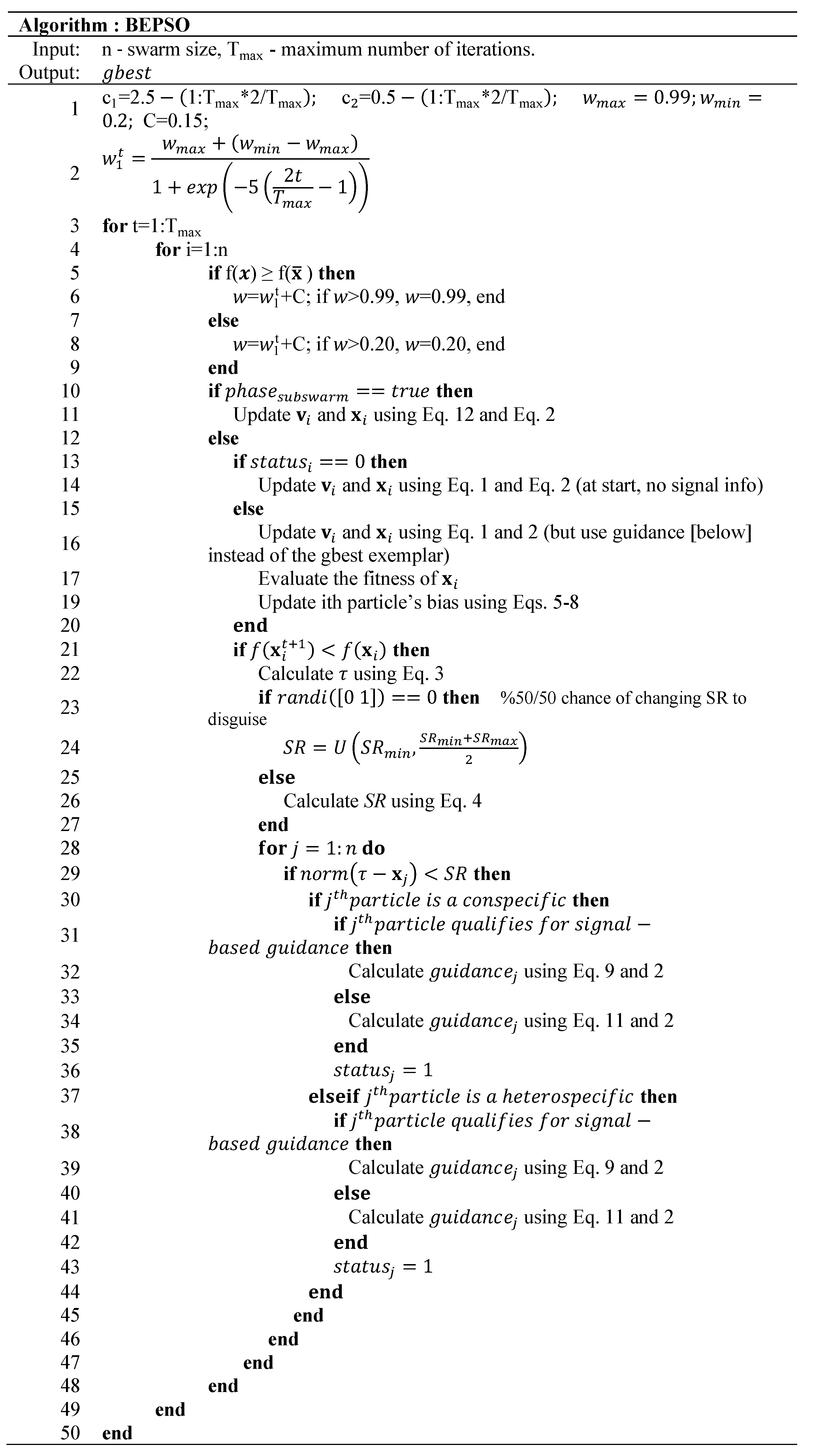

3.1. BEPSO: biased eavesdropping PSO

- Conspecific recipient particles decide to exploit signal information only if the recipient particle is positively biased or unbiased towards the signaller, and the signaller particle’s confidence in the newly discovered position is high.

- Eavesdropper particles decide to exploit signal information if the eavesdropper is positively or negatively biased towards the signaller, but the signaller’s confidence in the newly discovered position is high.

3.1.1. BEPSO Parameters

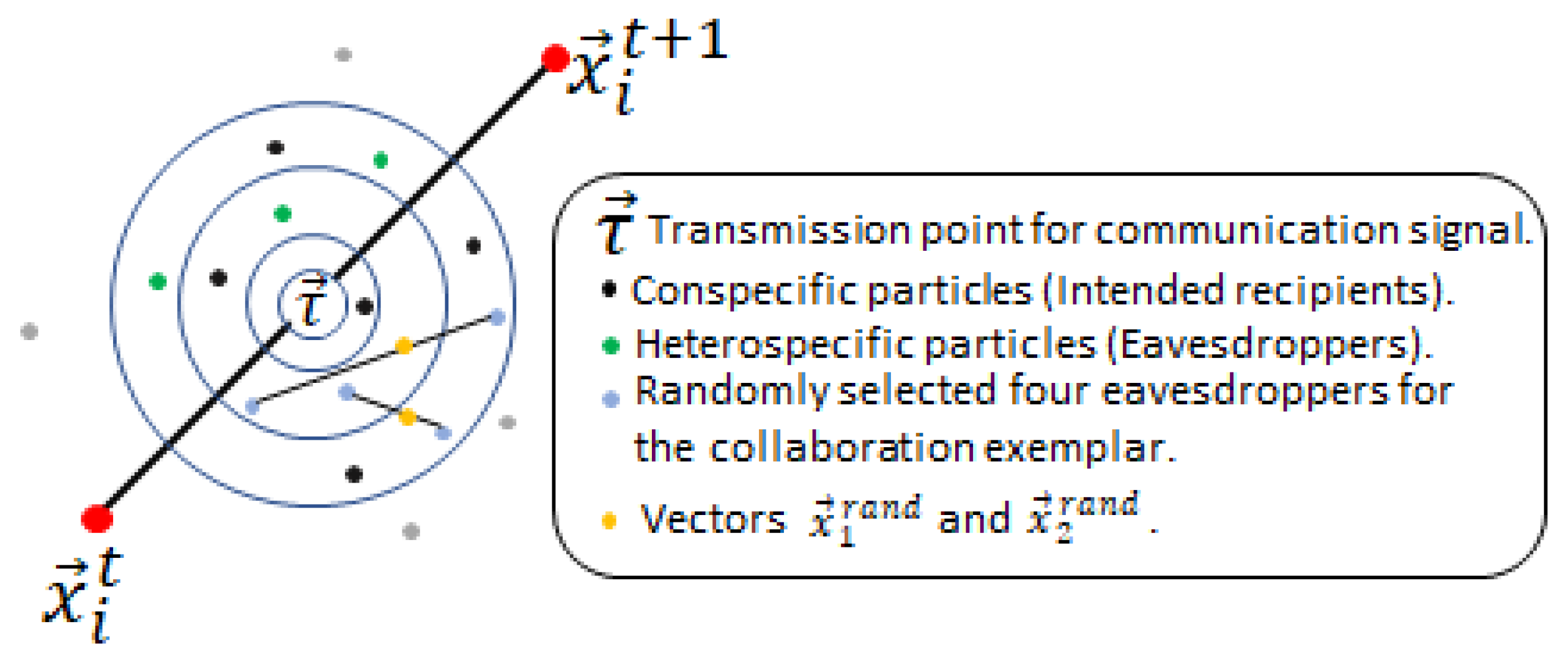

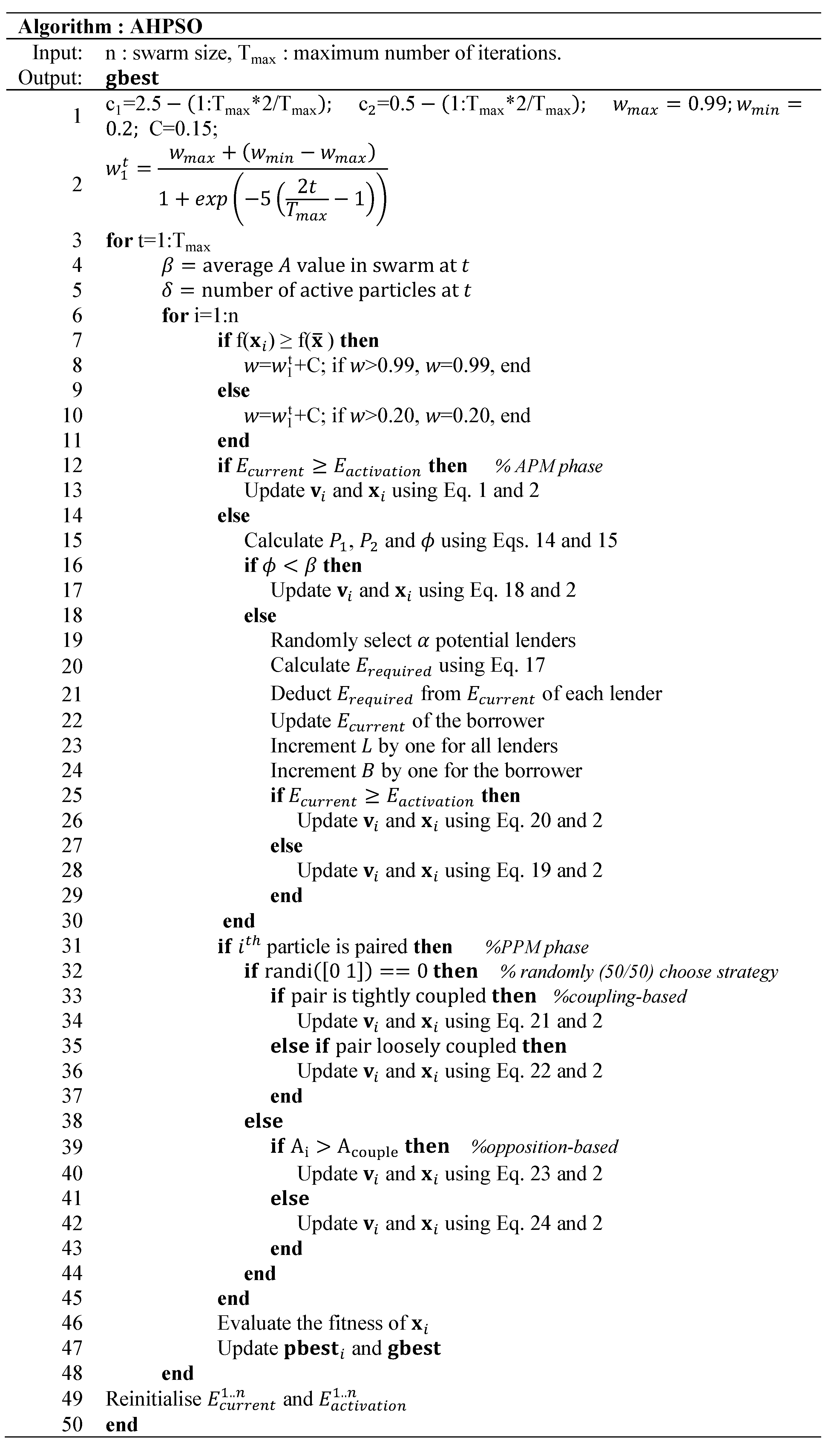

3.2. AHPSO: Altruistic Heterogeneous PSO

3.3. Altruistic Particle Model (APM)

3.4. Paired Particle Model (PPM)

3.4.1. Coupling-based Strategy

- A pair is tightly coupled, if both particles are active at time t.

- A pair is loosely coupled, if both particles are inactive at time t.

- A pair is neutral, if one particle is active and the other is inactive at time t.

3.4.2. Opposition-Based Strategy

3.5. The Search Process of AHPSO

3.5.1. AHPSO parameters

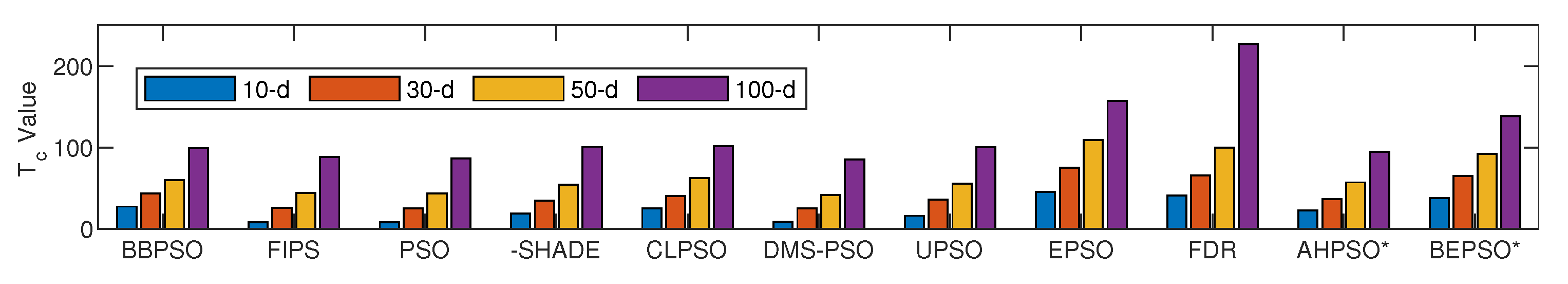

3.6. Comparative experiments

4. Results

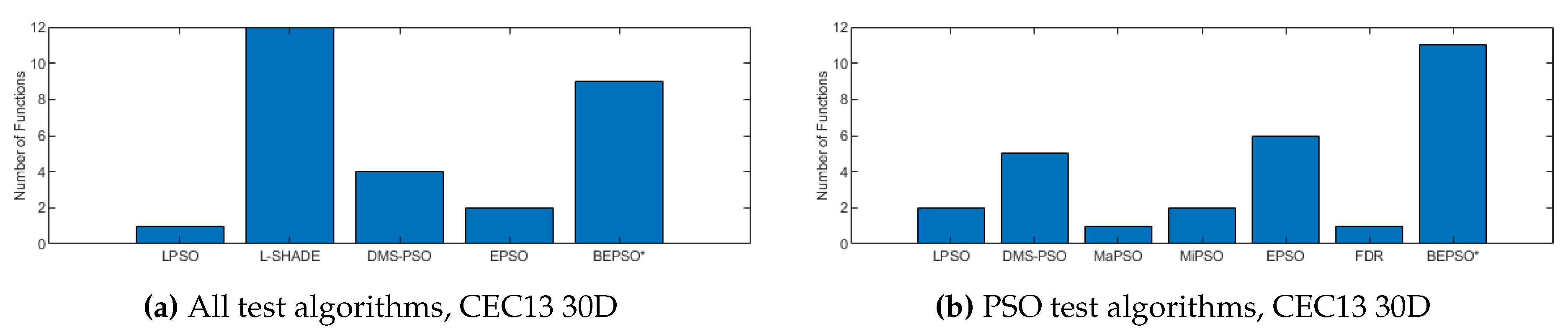

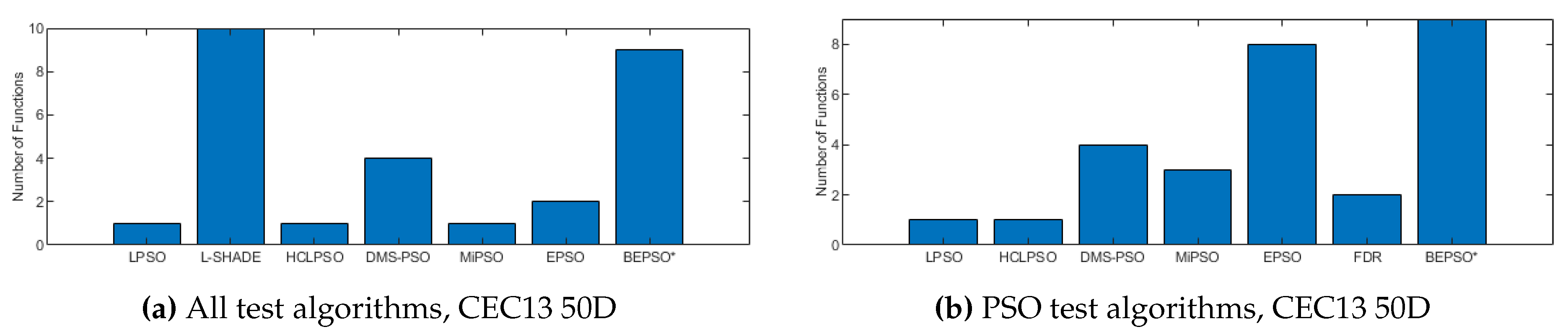

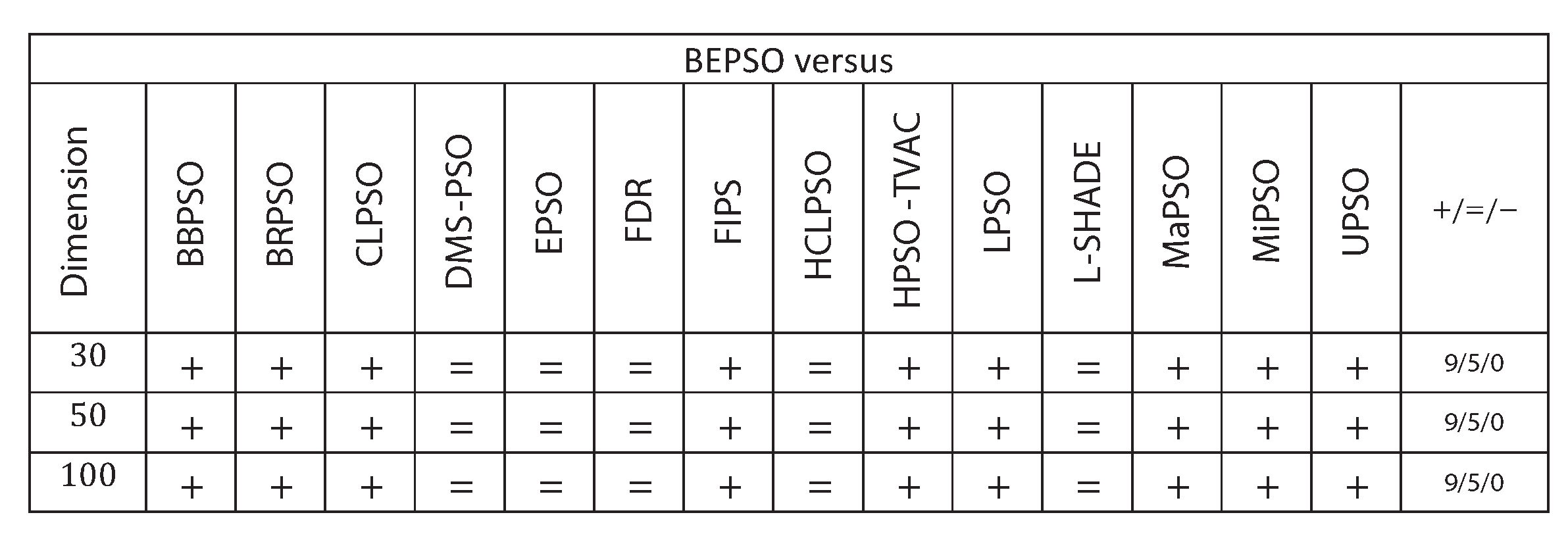

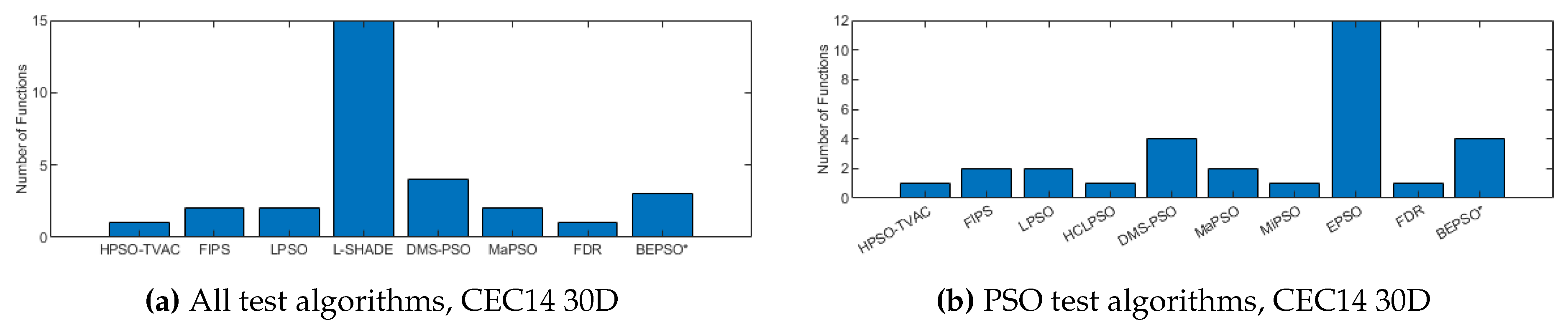

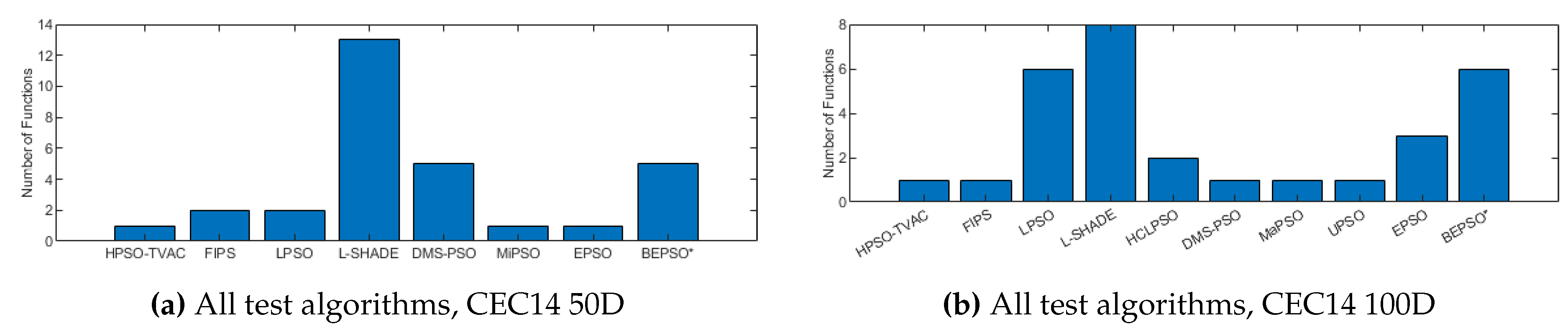

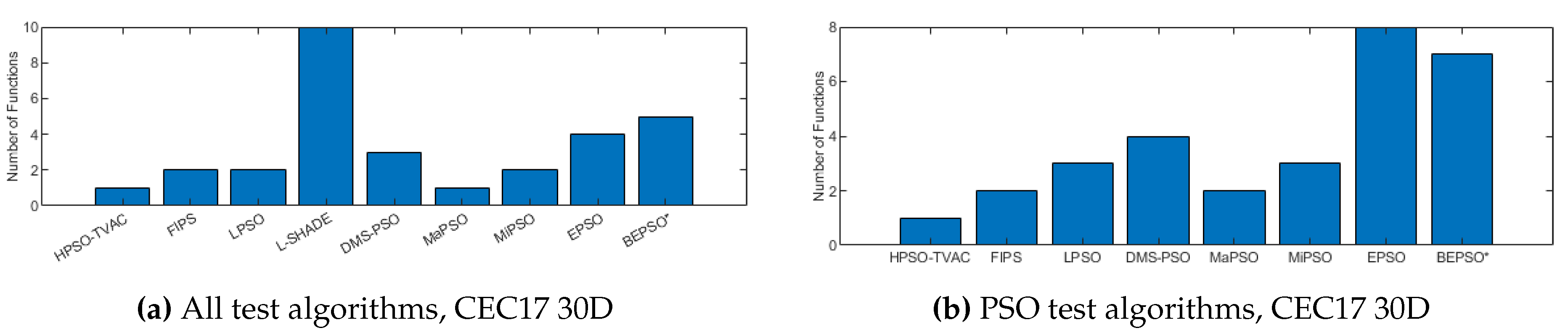

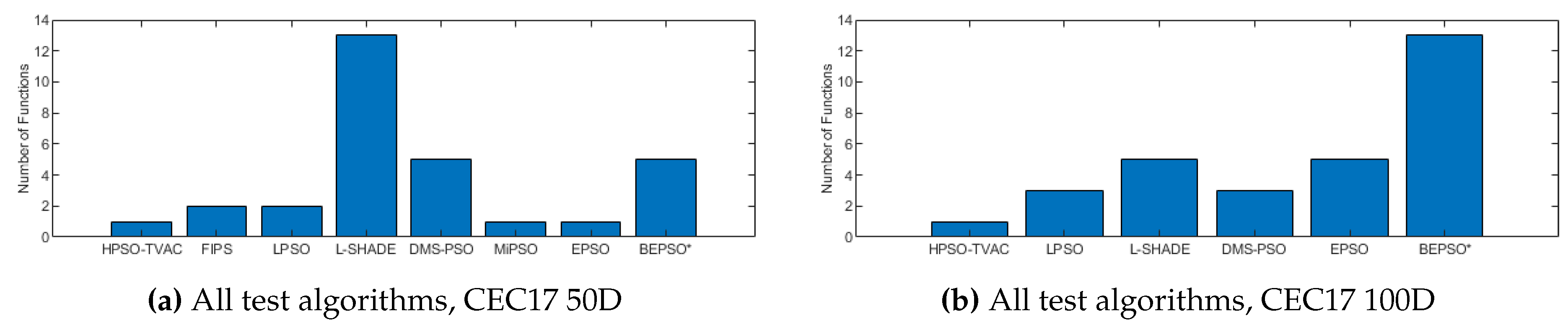

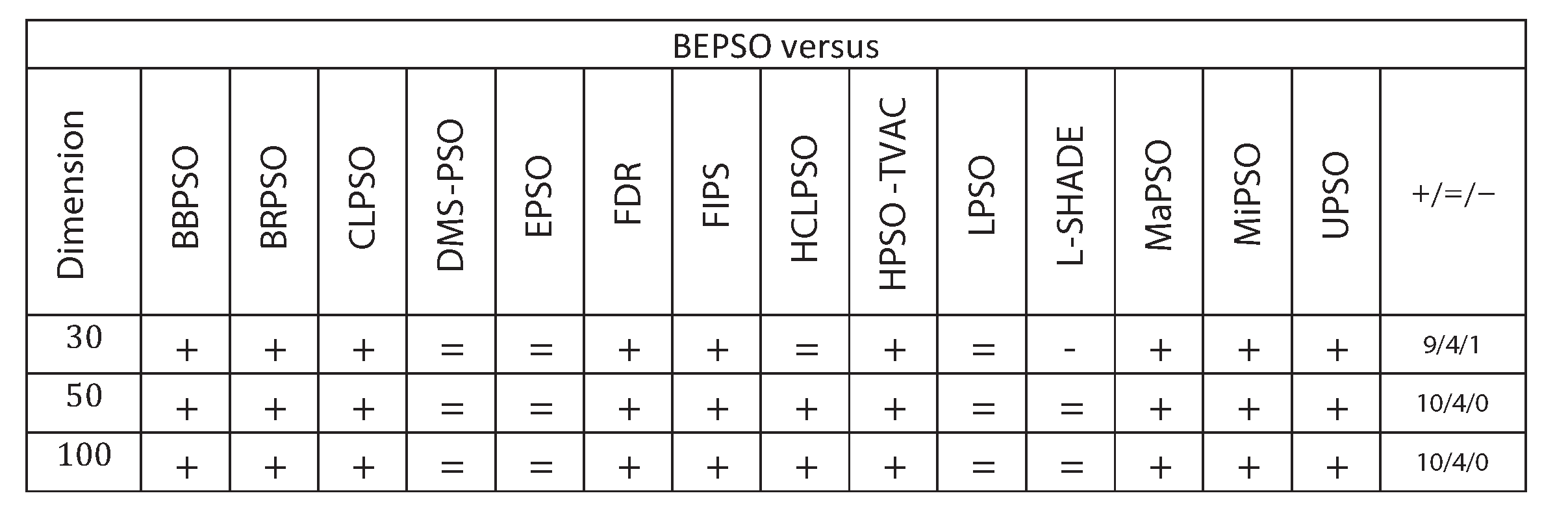

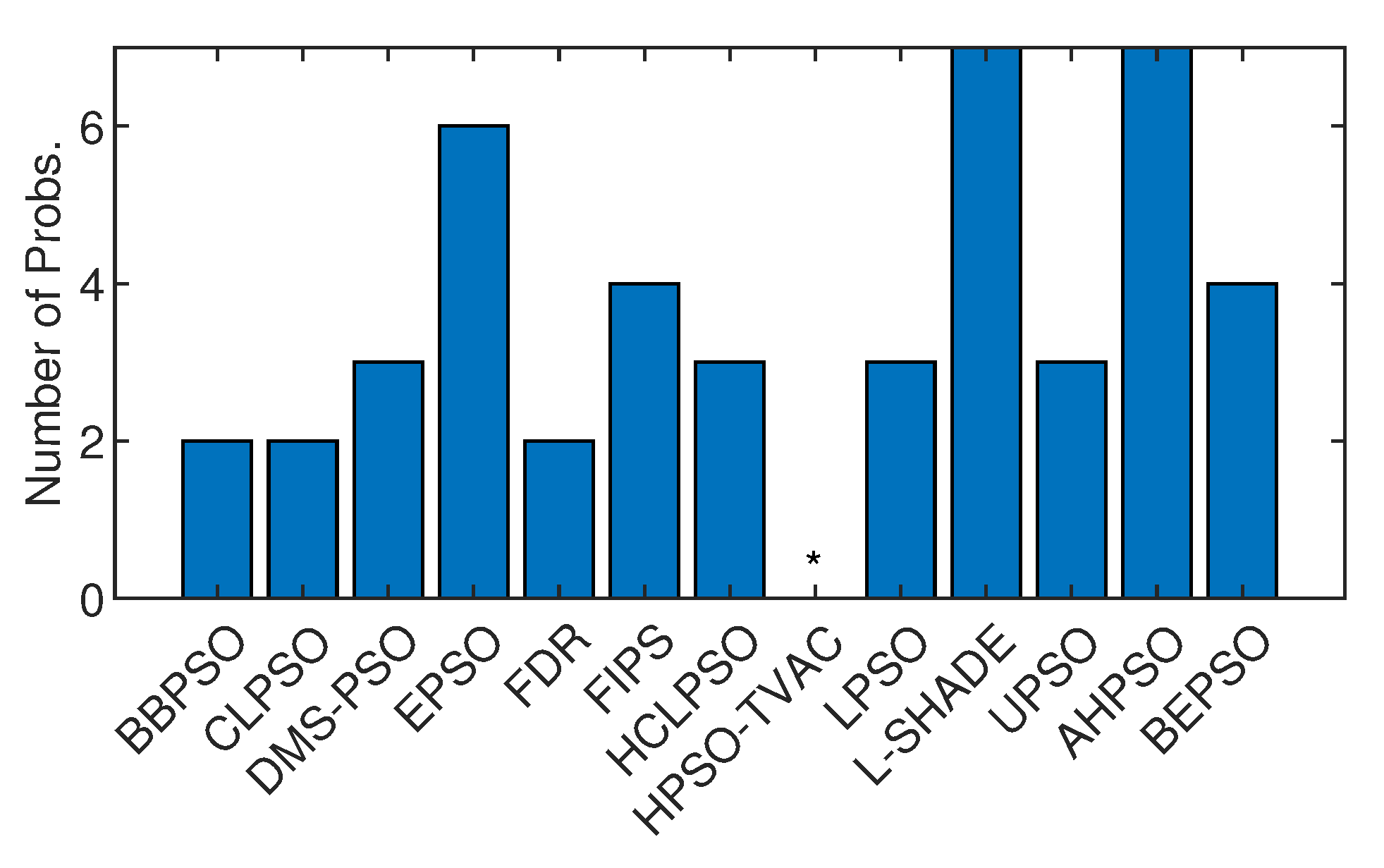

4.1. BEPSO: Performance

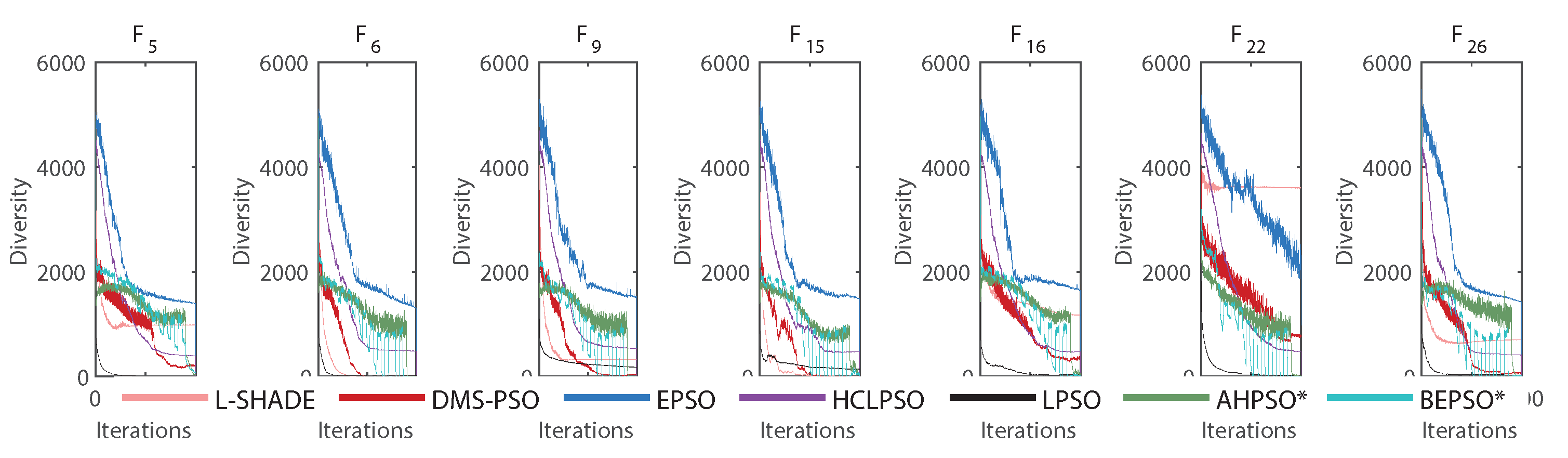

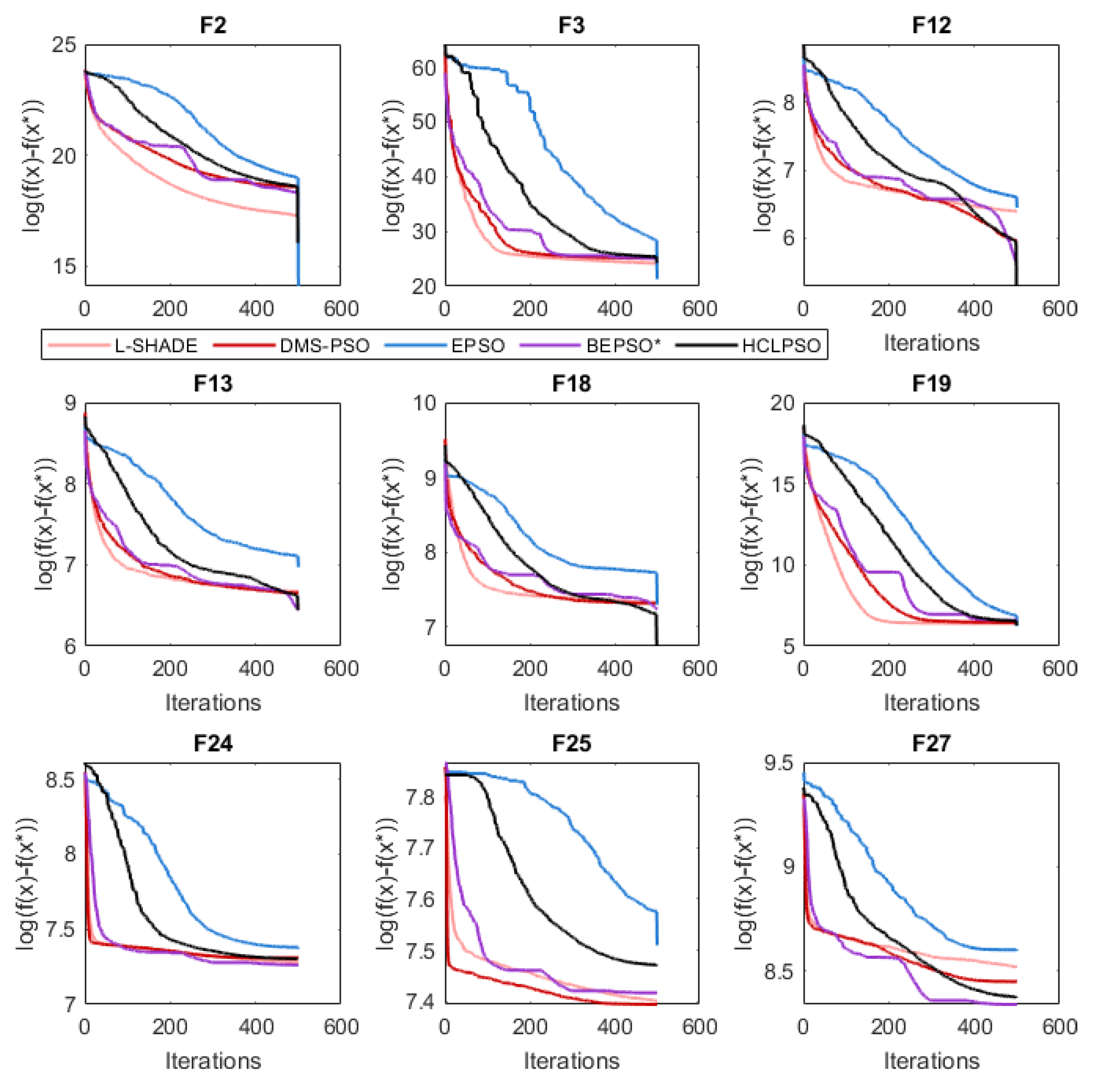

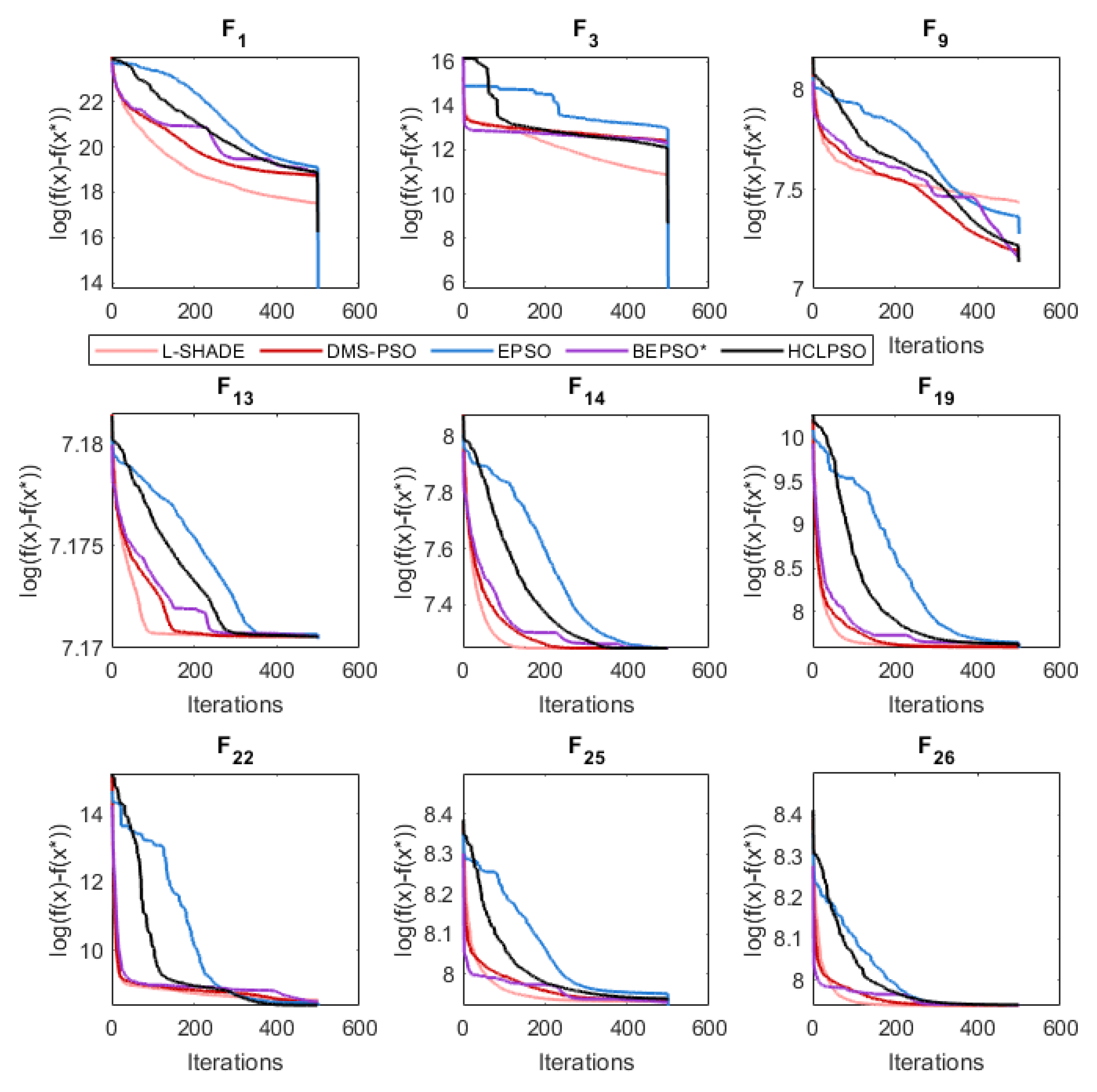

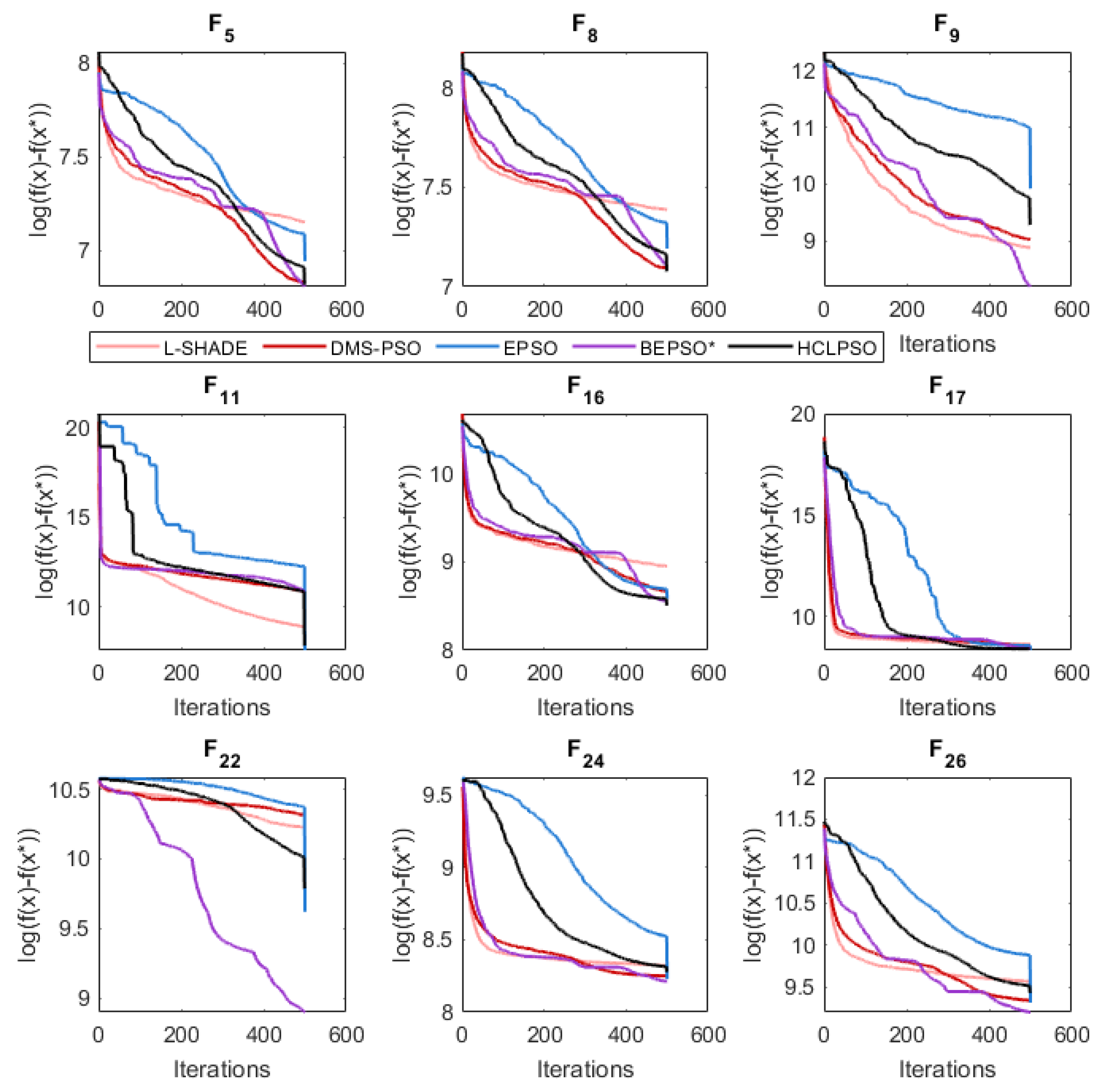

4.2. BEPSO: Convergence

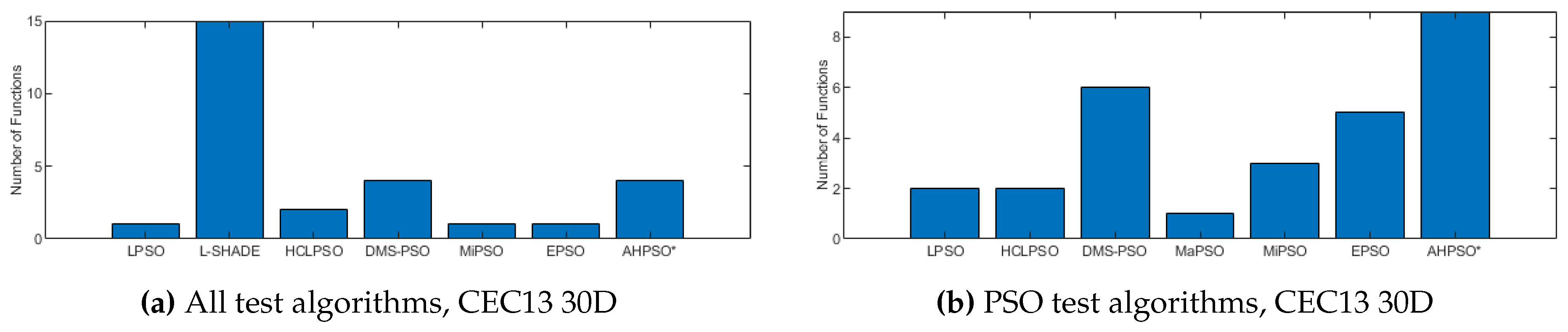

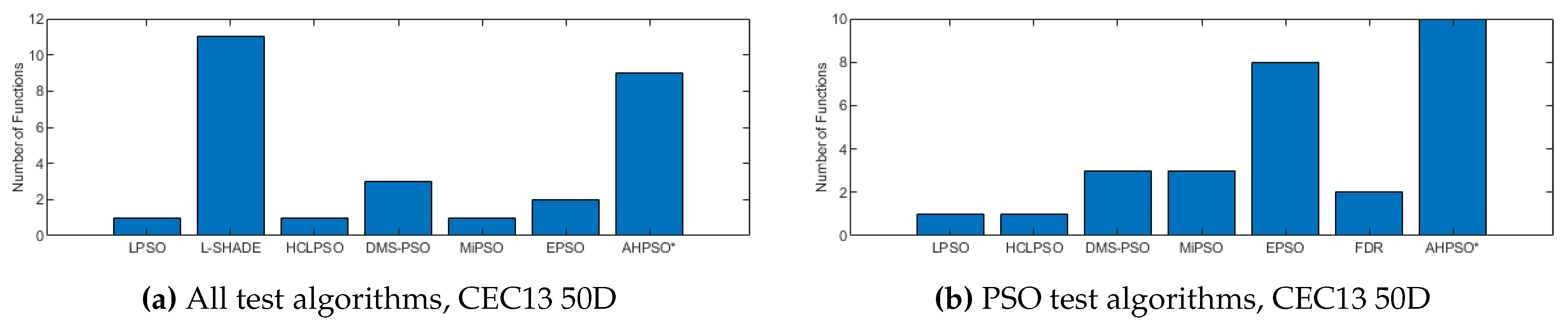

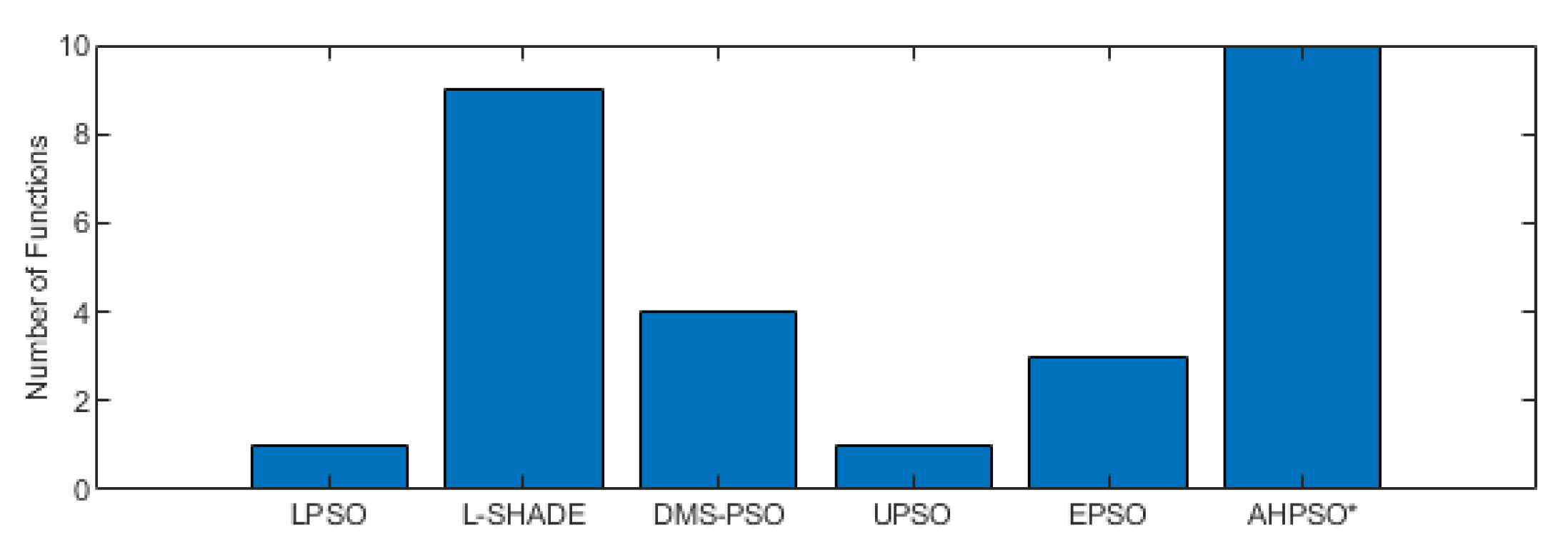

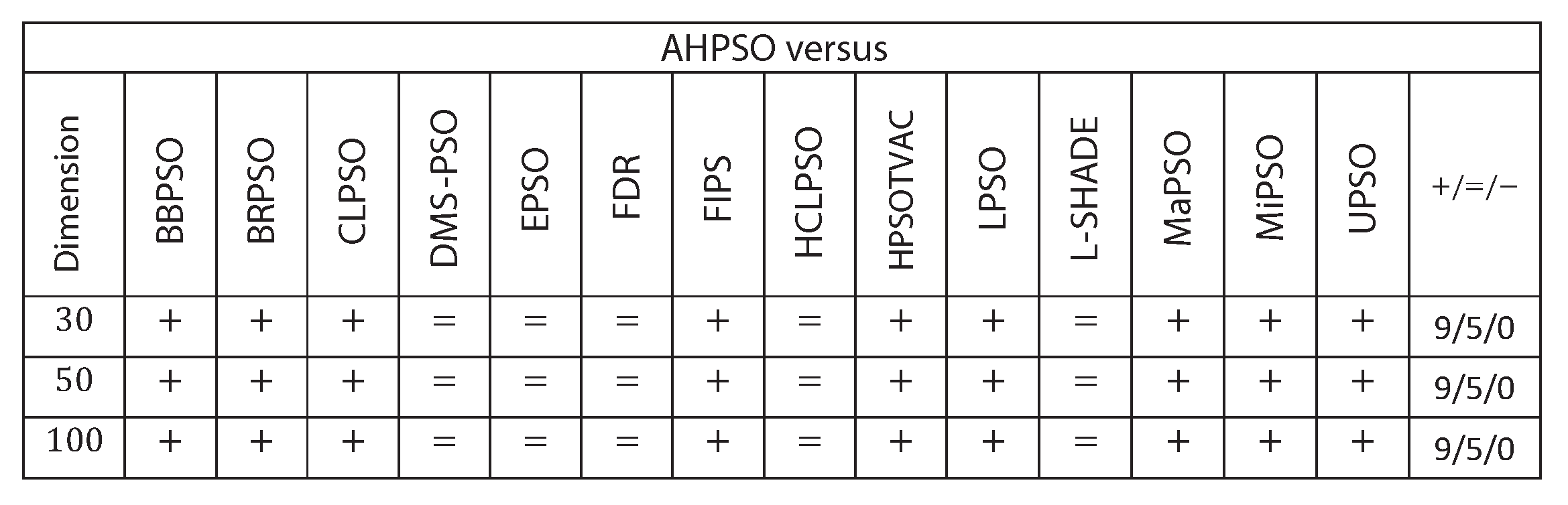

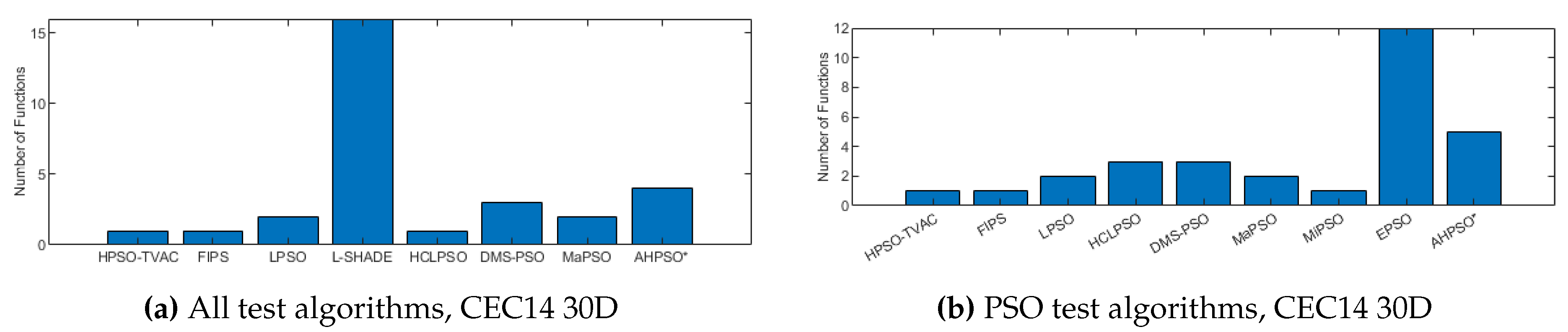

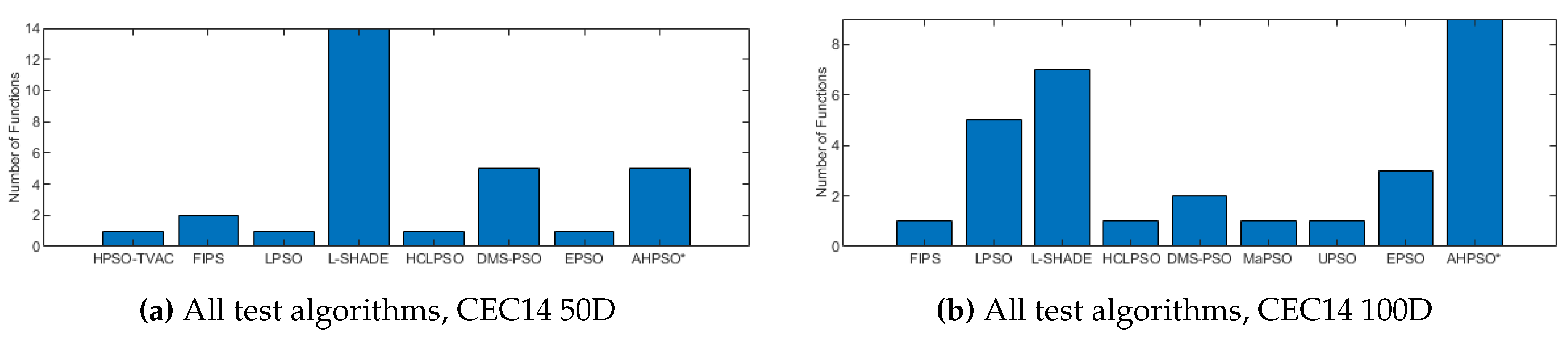

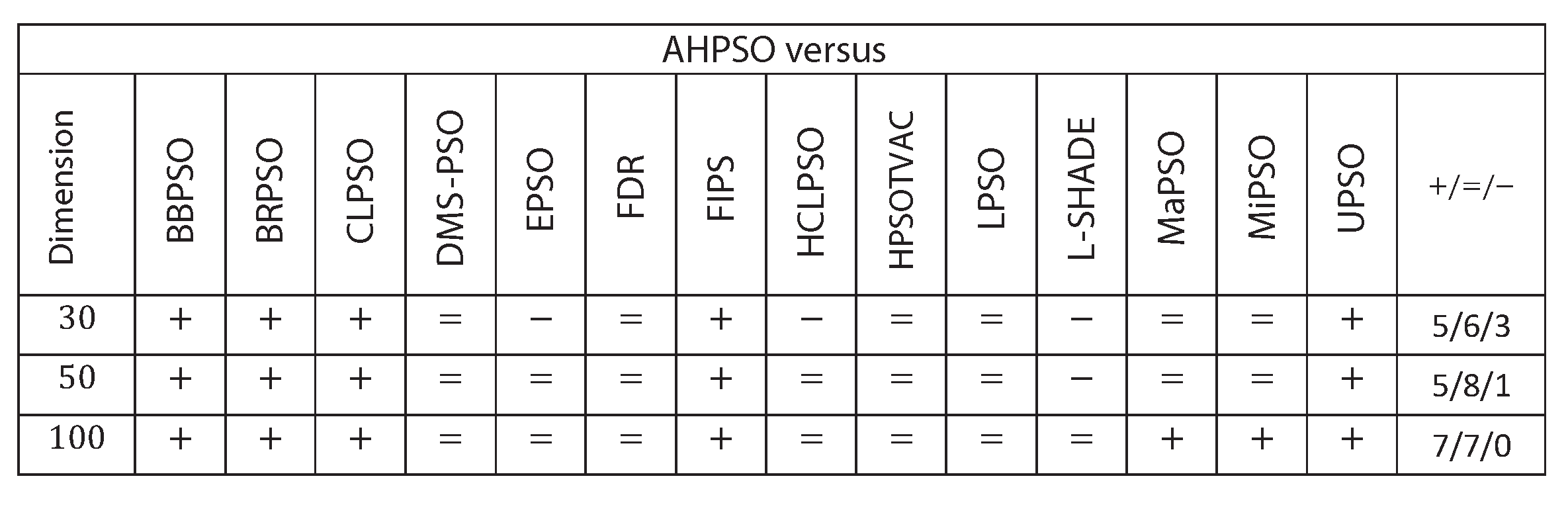

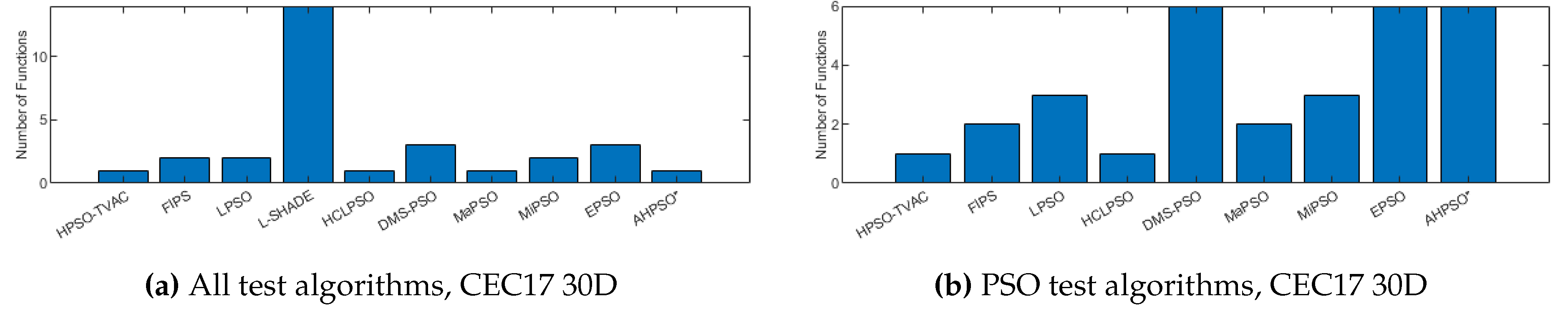

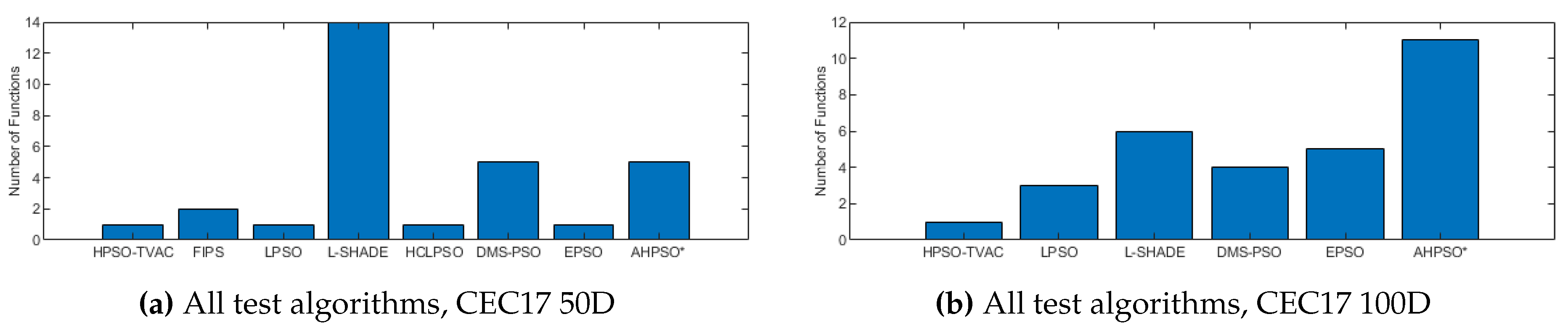

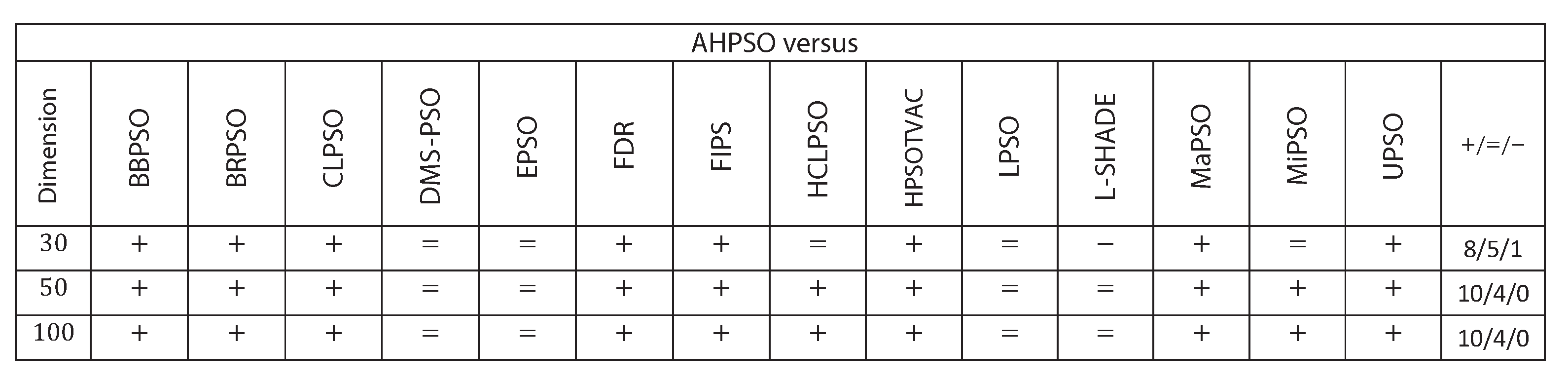

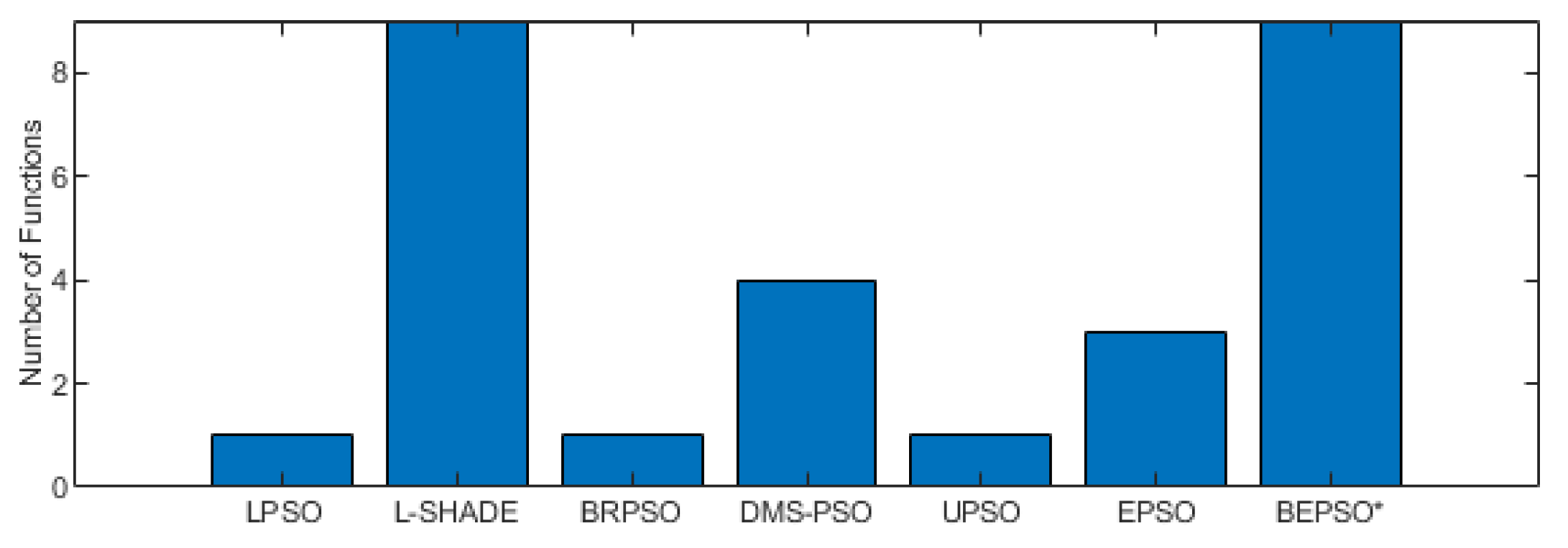

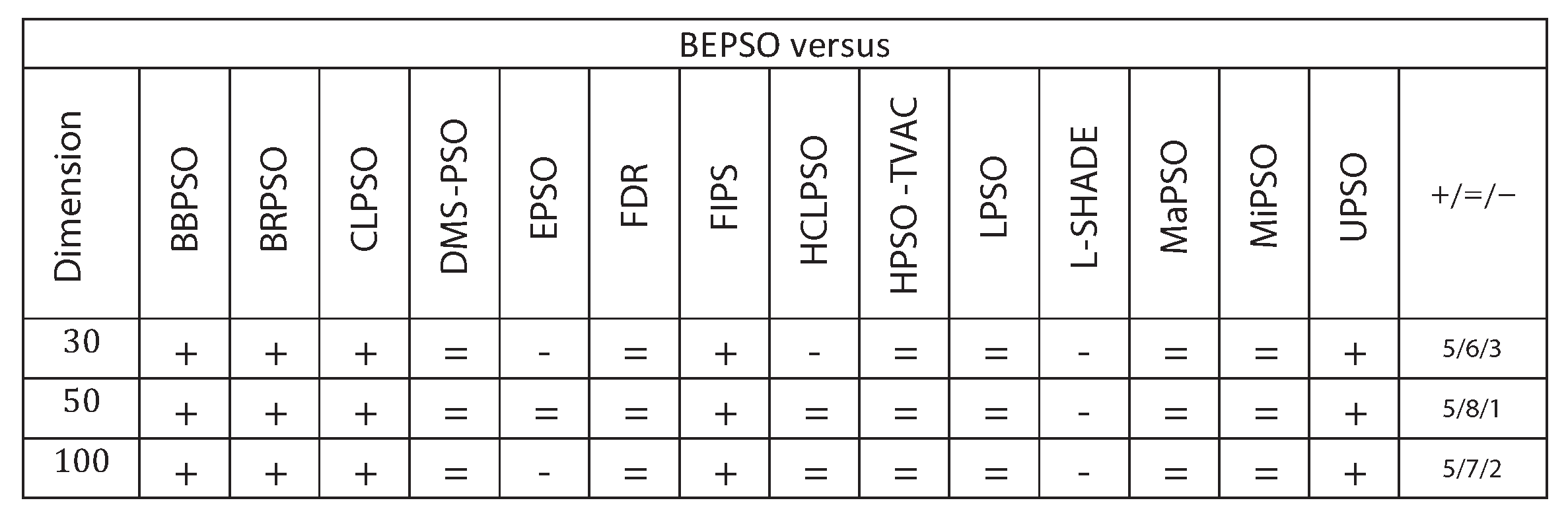

4.3. AHPSO: Performance

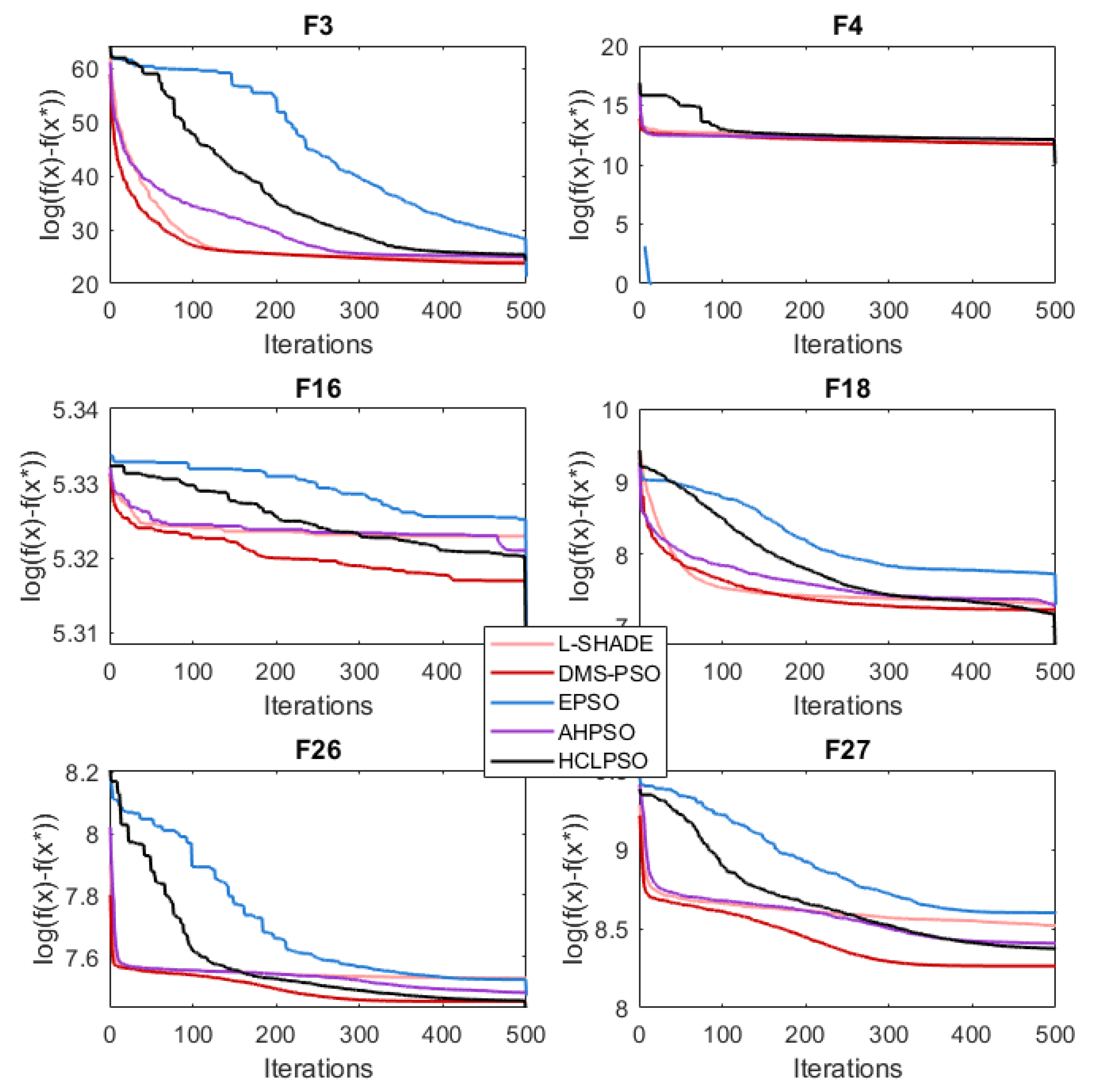

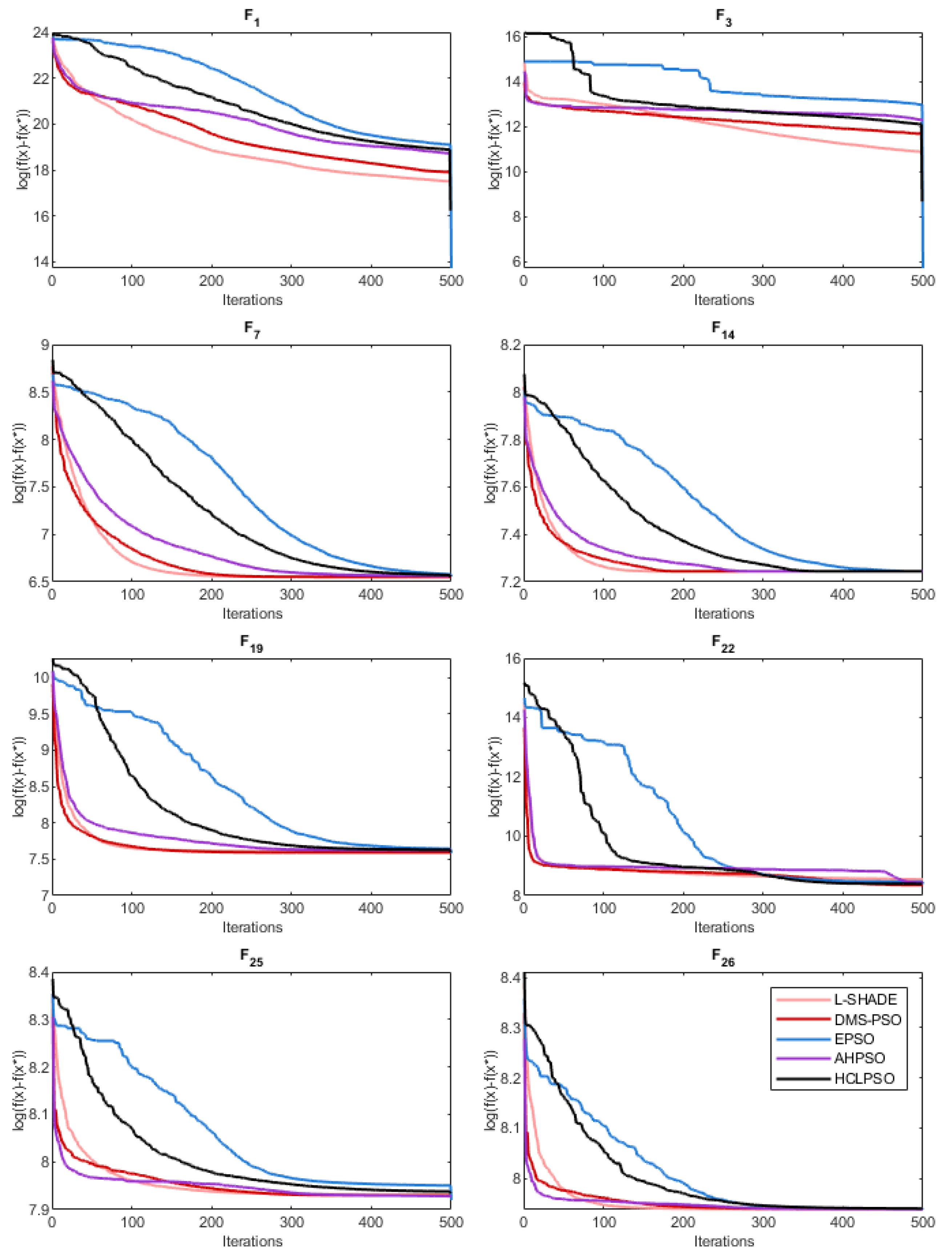

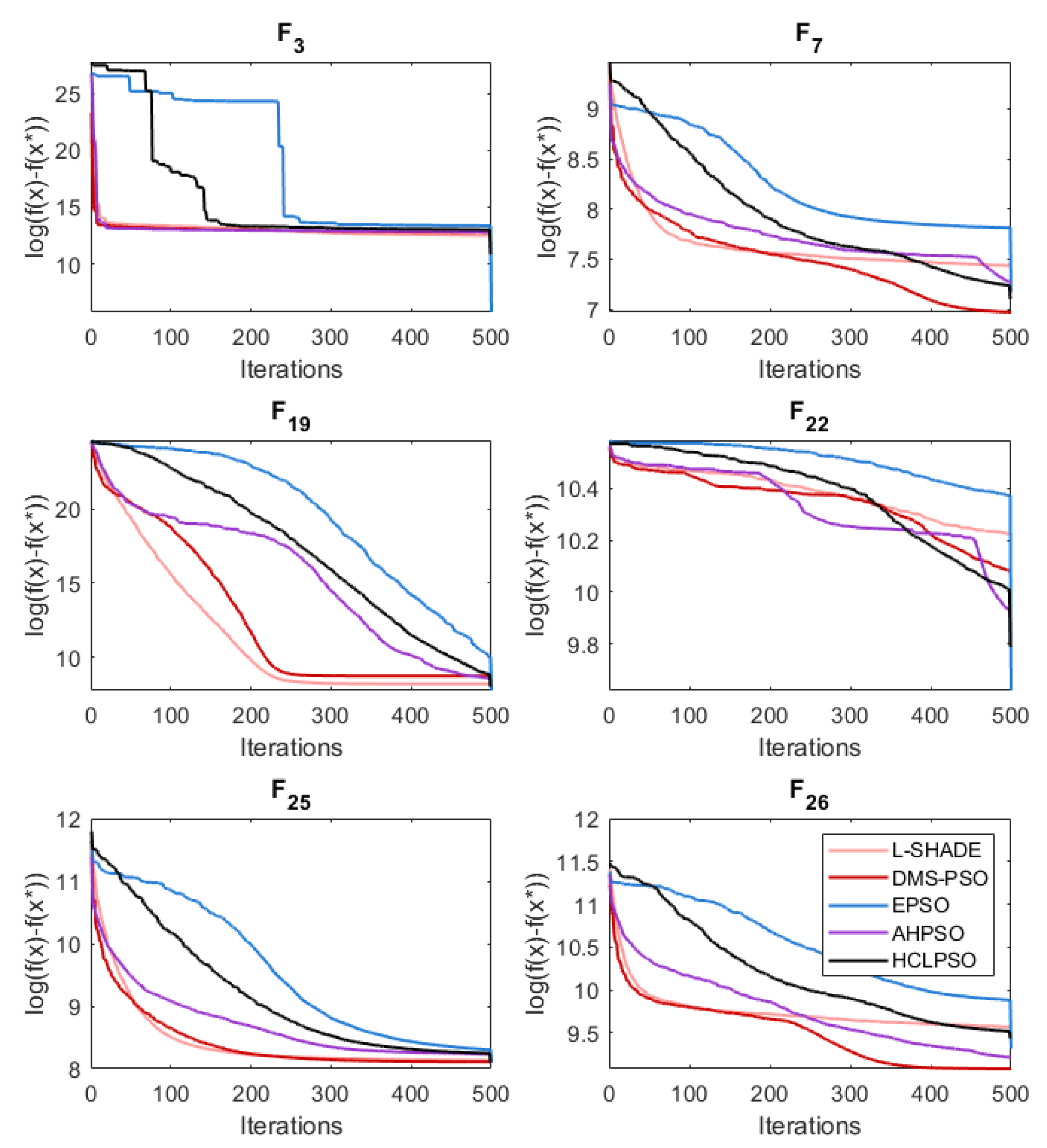

4.4. AHPSO: convergence

5. Constrained Optimisation Problems

6. Discussion

- Step 1 – Calculate the given code (according to the methodology in [35]) and record the computation time as .

- Step 2 – Calculate the computation time just for (CEC13 test suite) for function evaluations on dimension D, record as .

- Step 3 – Calculate the complete computation time for with function evaluations on the same dimension as .

- Step 4 – Repeat step 3 5 times and attain 5 individual values, .

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pham, Q.V.; Nguyen, D.C.; Mirjalili, S.; Hoang, D.T.; Nguyen, D.N.; Pathirana, P.N.; Hwang, W.J. Swarm intelligence for next-generation networks: Recent advances and applications. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2021, 191, 103141. [CrossRef]

- Camci, E.; Kripalani, D.R.; Ma, L.; Kayacan, E.; Khanesar, M.A. An aerial robot for rice farm quality inspection with type-2 fuzzy neural networks tuned by particle swarm optimization-sliding mode control hybrid algorithm. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2018, 41, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ehteram, M.; Binti Othman, F.; Mundher Yaseen, Z.; Abdulmohsin Afan, H.; Falah Allawi, M.; Bt. Abdul Malek, M.; Najah Ahmed, A.; Shahid, S.; P. Singh, V.; El-Shafie, A. Improving the Muskingum Flood Routing Method Using a Hybrid of Particle Swarm Optimization and Bat Algorithm. Water 2018, 10, 807. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ye, Y.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, H.; Shang, Y.; Wang, J. Remote sensing of water quality based on HJ-1A HSI imagery with modified discrete binary particle swarm optimization-partial least squares (MDBPSO-PLS) in inland waters: A case in Weishan Lake. Ecological Informatics 2018, 44, 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Thanga Ramya, S.; Arunagiri, B.; Rangarajan, P. Novel effective X-path particle swarm optimization based deprived video data retrieval for smart city. Cluster Computing 2019, 22, 13085–13094. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. Proceedings of ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks. IEEE, Vol. 4, pp. 1942–1948. [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A. Particle swarm optimization: Velocity initialization. 2012 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation. IEEE, 2012, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A.P.; Bosman, P.; Malan, K.M. The influence of fitness landscape characteristics on particle swarm optimisers. Natural Computing 2022, 21, 335–345. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Luo, Y.; Yang, S. Stochastic convergence analysis and parameter selection of the standard particle swarm optimization algorithm. Information Processing Letters 2007, 102, 8–16. [CrossRef]

- Trelea, I.C. The particle swarm optimization algorithm: convergence analysis and parameter selection. Information Processing Letters 2003, 85, 317–325. [CrossRef]

- Varna, F.T.; Husbands, P. HIDMS-PSO: A New Heterogeneous Improved Dynamic Multi-Swarm PSO Algorithm. 2020 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI). IEEE, 2020, pp. 473–480. [CrossRef]

- Varna, F.T.; Husbands, P. HIDMS-PSO with Bio-inspired Fission-Fusion Behaviour and a Quorum Decision Mechanism. 2021 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1398–1405. [CrossRef]

- Varna, F.T.; Husbands, P. Genetic Algorithm Assisted HIDMS-PSO: A New Hybrid Algorithm for Global Optimisation. 2021 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1304–1311. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Gao, M.; Cao, S.; Guo, A.; Wang, J. Heterogeneous comprehensive learning and dynamic multi-swarm particle swarm optimizer with two mutation operators. Information Sciences 2020, 540, 175–201. [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.R.; Chang, Y.D.; Lee, W.S. Maximum Power Point Tracking of Photovoltaic Generation System Using Improved Quantum-Behavior Particle Swarm Optimization. Biomimetics 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Cao, L.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Su, Z. Towards an Optimal KELM Using the PSO-BOA Optimization Strategy with Applications in Data Classification. Biomimetics 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, T.; Shanmugavel, S.; Rajesh, A. Hybrid HSA and PSO algorithm for energy efficient cluster head selection in wireless sensor networks. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2016, 30, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.M.; Pandey, H.M.; Amgoth, T. GAPSO-H: A hybrid approach towards optimizing the cluster based routing in wireless sensor network. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2021, 60, 100772. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Qin, A.; Suganthan, P.; Baskar, S. Comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer for global optimization of multimodal functions. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2006, 10, 281–295. [CrossRef]

- Lynn, N.; Suganthan, P.N. Heterogeneous comprehensive learning particle swarm optimization with enhanced exploration and exploitation. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2015, 24, 11–24. [CrossRef]

- Changhe Li.; Shengxiang Yang.; Trung Thanh Nguyen. A Self-Learning Particle Swarm Optimizer for Global Optimization Problems. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 2012, 42, 627–646. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J. Small worlds and mega-minds: effects of neighborhood topology on particle swarm performance. Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation-CEC99 (Cat. No. 99TH8406). IEEE, 1999, pp. 1931–1938. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Mendes, R. Population structure and particle swarm performance. Proceedings of the 2002 Congress on Evolutionary Computation, CEC 2002. IEEE, 2002, Vol. 2, pp. 1671–1676. [CrossRef]

- Suganthan, P. Particle swarm optimiser with neighbourhood operator. Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation-CEC99 (Cat. No. 99TH8406). IEEE, pp. 1958–1962. [CrossRef]

- Varna, F.T.; Husbands, P. HIDMS-PSO Algorithm with an Adaptive Topological Structure. 2021 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.J.; Suganthan, P.N. Dynamic multi-swarm particle swarm optimizer. Proceedings - 2005 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium, SIS 2005. IEEE, 2005, Vol. 2005, pp. 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Trillo, P.A.; Benson, C.S.; Caldwell, M.S.; Lam, T.L.; Pickering, O.H.; Logue, D.M. The Influence of Signaling Conspecific and Heterospecific Neighbors on Eavesdropper Pressure. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Lilly, M.V.; Lucore, E.C.; Tarvin, K.A. Eavesdropping grey squirrels infer safety from bird chatter. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0221279. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.D. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1964, 7, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G. Cooperation: How Vampire Bats Build Reciprocal Relationships. Current Biology 2020, 30, R307–R309. [CrossRef]

- Connor, R.C. Pseudo-reciprocity: Investing in mutualism. Animal Behaviour 1986, 34, 1562–1566. [CrossRef]

- Wickelgren, W.A. Speed-accuracy tradeoff and information processing dynamics. Acta Psychology 1977, 41, 67–85.

- Varna, F.T. Design and Implementation of Bio-inspired Heterogeneous Particle Swarm Optimisation Algorithms for Unconstrained and Constrained Problems. Phd thesis, University of Sussex, 2023.

- Varna, F.T.; Husbands, P. BIS: A New Swarm-Based Optimisation Algorithm. 2020 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI). IEEE, 2020, pp. 457–464. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Qu, B.; Suganthan, P. Problem Definitions and Evaluation Criteria for the CEC 2013 Special Session on Real-Parameter Optimization, Vol. 34: Technical Report 201212. Technical report, Computational Intelligence Laboratory, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China and Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2013.

- Liang, J.; Qu, B.; Suganthan, P. Problem Definitions and Evaluation Criteria for the CEC 2014 Special Session and Competition on Single Objective Real-Parameter Numerical Optimization. Technical report, Computational Intelligence Laboratory, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou China and Technical Report, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2014.

- Awad, N.; Ali, M.; Suganthan, P.; Liang, J.; Qu, B. Problem Definitions and Evaluation Criteria for the CEC 2017 Special Session and Competition on Single Objective Real-Parameter Numerical Optimization. Technical report, School of EEE, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, School of Computer Information Systems, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan, School of Electrical Engineering, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2016.

- Yue, N.; Yue, P.; Price, K.; Suganthan, P.; Liang, J.; Ali, M.; Qu, B. Problem Definitions and Evaluation Criteria for the CEC 2020 Special Session and Competition on Single Objective Bound Constrained Numerical Optimization, 2019.

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A.S. Improving the search performance of SHADE using linear population size reduction. 2014 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC). IEEE, 2014, pp. 1658–1665. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J. Bare bones particle swarms. Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium. SIS’03 (Cat. No.03EX706). IEEE, pp. 80–87. [CrossRef]

- Settles, M.; Soule, T. Breeding swarms. Proceedings of the 2005 conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation - GECCO ’05; ACM Press: New York, New York, USA, 2005; p. 161. [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.; Kennedy, J.; Neves, J. The Fully Informed Particle Swarm: Simpler, Maybe Better. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2004, 8, 204–210. [CrossRef]

- Peram, T.; Veeramachaneni, K.; Mohan, C. Fitness-distance-ratio based particle swarm optimization. Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE Swarm Intelligence Symposium. SIS’03 (Cat. No.03EX706). IEEE, pp. 174–181. [CrossRef]

- Parsopoulos, K.; Vrahatis, M. UPSO: A Unified Particle Swarm Optimization Scheme. In International Conference of Computational Methods in Sciences and Engineering 2004 (ICCMSE 2004); CRC Press, 2019; pp. 868–873. [CrossRef]

- Lynn, N.; Suganthan, P.N. Ensemble particle swarm optimizer. Applied Soft Computing 2017, 55, 533–548. [CrossRef]

- Ratnaweera, A.; Halgamuge, S.; Watson, H. Self-Organizing Hierarchical Particle Swarm Optimizer With Time-Varying Acceleration Coefficients. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2004, 8, 240–255. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation 1998. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Hasanzadeh, M.; Meybodi, M.R.; Ebadzadeh, M.M. Adaptive Parameter Selection in Comprehensive Learning Particle Swarm Optimizer; 2014; pp. 267–276. [CrossRef]

- Derrac, J.; Garcia, S.; Molina, D.; Herrera, F. A practical tutorial on the use of nonparametric statistical tests as a methodology for comparing evolutionary and swarm intelligence algorithms. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2011, 1, 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Wu, G.; Ali, M.Z.; Mallipeddi, R.; Suganthan, P.N.; Das, S. A test-suite of non-convex constrained optimization problems from the real-world and some baseline results. Swarm and Evolutionary Computation 2020, 56, 100693. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Engelbrecht. Fundamentals of Computational Swarm Intelligence; Wiley, 2005.

- Li, W.; Meng, X.; Huang, Y.; Fu, Z.H. Multipopulation cooperative particle swarm optimization with a mixed mutation strategy. J. Inf. Sci. 2020, 529, 179–196. [CrossRef]

- Wood, D. Hybrid cuckoo search optimization algorithms applied to complex wellbore trajectories aided by dynamic, chaos-enhanced, fat-tailed distribution sampling and metaheuristic profiling. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 34, 236–252. [CrossRef]

- Husbands, P.; Philippides, A.; Vargas, P.; Buckley, C.; Fine, P.; DiPaolo, E.; O’Shea, M. Spatial, temporal, and modulatory factors affecting GasNet evolvability in a visually guided robotics task. Complexity 2010, 16, 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Edelman, G.; Gally, J. Degeneracy and complexity in biological systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 13763––13768. [CrossRef]

- Whitacre, J.; Bender, A. Degeneracy: A design principle for achieving robustness and evolvability. J. Theor. Biol. 2010, 263, 143–153. [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No Free Lunch Theorems for Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 1997, 1, 67–82. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.; Yadav, A. Optimizing the parameters of hybrid active power filters through a comprehensive and dynamic multi-swarm gravitational search algorithm. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 123, 106469. [CrossRef]

| Key | Algorithm | Parameters |

| L-Shade [39] | SHADE with linear population reduction | see [39] |

| BBPSO [40] | Bare bones PSO | see [40] |

| BreedingPSO [41] | A GA/PSO hybrid | w=0.8 - 0.6, |

| HCLPSO [20] | Heterogeneous comprehensive learning PSO | w=0.99–0.29,, |

| CLPSO [19] | Comprehensive learning PSO | w=0.9–0.2; |

| FIPS [42] | Fully informed PSO | |

| FDR-PSO [43] | Fitness distance ratio PSO | w=0.9–0.4, |

| UPSO [44] | Unified PSO | |

| EPSO [45] | Ensemble PSO | see [45] |

| DMS-PSO [26] | Dynamic multi-swarm PSO | |

| HPSO-TVAC [46] | Hierarchical PSO, time-varying coefficients | |

| LPSO [47] | Linearly decreasing inertial weight PSO | |

| maPSO [48] | macroscopic PSO | |

| miPSO [48] | microscopic PSO |

| Problem | D | g | h | ||

| Process Synthesis and Design Problems | |||||

| RC01 | Process flow sheeting problem | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1.0765430833E+00 |

| RC02 | Process synthesis problem | 7 | 9 | 0 | 2.9248305537E+00 |

| Mechanical Engineering Problems | |||||

| RC03 | Weight minimization of a speed reducer | 7 | 11 | 0 | 2.9944244658E+03 |

| RC04 | Pressure vessel design | 4 | 4 | 0 | 5.8853327736E+03 |

| RC05 | Three-bar truss design problem | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2.6389584338E+02 |

| RC06 | Step-cone pulley problem | 5 | 8 | 3 | 1.6069868725E+01 |

| RC07 | 10-bar truss design | 10 | 3 | 0 | 5.2445076066E+02 |

| RC08 | Rolling element bearing | 10 | 9 | 0 | 1.4614135715E+04 |

| RC09 | Gas transmission compressor design | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2.9648954173E+06 |

| RC10 | Gear train design | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.0000000000E+00 |

| Power Electronic Problems | |||||

| RC11 | SOPWM for 7-level inverters | 25 | 24 | 1 | 1.5164538375E-02 |

| RC12 | SOPWM for 8-level inverters | 30 | 29 | 1 | 1.6787535766E-02 |

| RC13 | SOPWM for 11-level inverters | 30 | 29 | 1 | 9.3118741800E-03 |

| RC14 | SOPWM for 13-level inverters | 30 | 29 | 1 | 1.5096451396E-02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).