1. Introduction

The Coffin-Siris syndrome (CSS) is a multisystem congenital anomaly caused by mutations in genes of BRG1- and BRM-associated factors complex, including

ARID1A,

ARID1B,

ARID2,

DPF2,

SMARCA4,

SMARCB1,

SMARCC2,

SMARCE1,

SOX11, and

SOX4. [

1,

2,

3]

Recent discoveries underlined the importance of the BAF complex in the human neuronal development and cancer occurrence (three especially well-studied complex assemblies are esBAF, npBAF and nBAF): mutations in their subunit genes and related genes are implicated in several nonverbal ID (intellectual disability) syndromes such as CSS, autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia as well as in cancers/cancer predisposing syndromes [

4,

5].

In 1970, Coffin and Siris were the first ones to describe 3 girls with similar phenotypic traits and manifestations: severe mental retardation and developmental delay, growth retardation, lax joints, and absent or hypoplastic fifth distal phalanges and nails [

6]. Other findings were coarse facial appearance, feeding difficulties, frequent infections, cardiac/neuro- logical/gastrointestinal/genitourinary anomalies [

7].

The typical features of Coffin Siris syndrome result from the involvement of ectodermal tissues. Abnormal or delayed dentition is also reported frequently. [

8,

9]

Fewer than 200 individuals with molecularly confirmed Coffin-Siris syndrome have been reported, indicating and underlining that the diagnosis is rare and difficult. It has to be considered that these numbers are likely underestimated, since not all individuals may have come to medical attention.

In addition, the identification of a pathogenic variant in

ARID1B in some members of a large cohort with intellectual disability suggests that the prevalence of pathogenic variants in genes associated with CSS (and of subtle phenotypic features of CSS) may be higher than currently appreciated among those with intellectual disability [

10,

11].

Penetrance for Coffin-Siris syndrome appears to be complete.

More females than males with CSS were reported in the literature prior to 2001 [

12]. In cases of molecularly confirmed CSS, male:female ratios are similar [

13,

14]. No evidence exists for X-linked dominant, sex-limited, or mitochondrial inheritance [

15]

Individuals with Coffin-Siris syndrome have a distinct appearance with overall typical coarse facial features. In early childhood individuals with CSS usually have round face with thick and arched eyebrows, short nose with bulbous tip and anteverted nostrils, long philtrum, small mouth, and micro-retrognathia. Adults tend to have broad nasal bridge without anteverted nostrils, broad philtrum, large tongue and prognathism [

16].

Common findings include wide mouth and thick lips. The palate is generally high arched and cleft palate is occasionally present. Another common feature is abnormal ears, either in shape or position. Less frequent findings are ptosis, short philtrum and macroglossia. [

17]

Because of micrognathia, macroglossia, hypotonia, and lax joint, dental and orthodontic management can be challenging in these children as well as the communication because of the ID. Dentists should be aware that proper motivation and psychological support for the patients and their families are essential to achieve a functional and esthetical dentition and occlusion. [

18,

19]

The most common and significant oral health problems in these patients are gingival and periodontal diseases, which usually lead to the loss of permanent anterior teeth in their young adulthood. Some factors can contribute to such evolution, including malocclusion, bruxism, conical-shaped tooth roots, and abnormal host response because of a compromised immune system [

20].

This article describes the treatment of a patient affected by CSS through orthognathic surgery and pre- and post-surgical orthodontic treatment.

The patient showed a problematic condition with a significant malocclusion characterized by mandibular prognathism, extremely narrow palate, anterior reverse bite, right and left cross bite.

This, combined with the facial dysmorphism typical of CSS, caused significant social, functional and aesthetic problems that the patient perceived as disturbing, requesting us to solve especially her aesthetic condition during the first visit [

21].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Presentation

The patient suffering from CSS came in the Orthodontic Department of the Gabriele D'Annunzio Odontostomatological Clinic in April 2016. The reasons for the visit were third class malocclusion and impacted second upper premolar (1.5).

The patient underwent a comprehensive clinical examination at the age of 26. The girl suffered from CSS and despite her ID she proved good communication skills. Her periodontal condition was good, she had not lost any periodontal support tissue or permanent elements, but her oral hygiene needed to be increased and improved. She was extensively educated and motivated at oral hygiene procedures before, during and after the treatment. During the whole treatment period we were strongly supported by her family and therapists who followed her closely at home.

Due to the anterior reverse bite, the patient was unable to chew, speak and breathe properly. She also had debilitating aesthetic problems because she was deeply ashamed of her smile. Giving this patient a better smile was crucial to motivate her to take care of her oral hygiene, and therefore to prevent her from incurring periodontal and dental problems at a young age.

Furthermore, due to the CSS, the patient had significant retinopathy which had significantly reduced her vision.

2.2. Clinical Assessment

The patient was 26 years old. The orthodontic examination assessed the following characteristics:

- Mesiofacial biotype

- Competent lips, prognathic profile

- Third molar and canine dental class, both right and left

- Anterior crossbite

- Negative overjet (approximately -3mm), increased overbite (approximately +5mm)

- Right and left posterior crossbite

- Lower midline left deviation approximately 3 mm

- Narrow upper arch with diastemas due to the absence of element 15

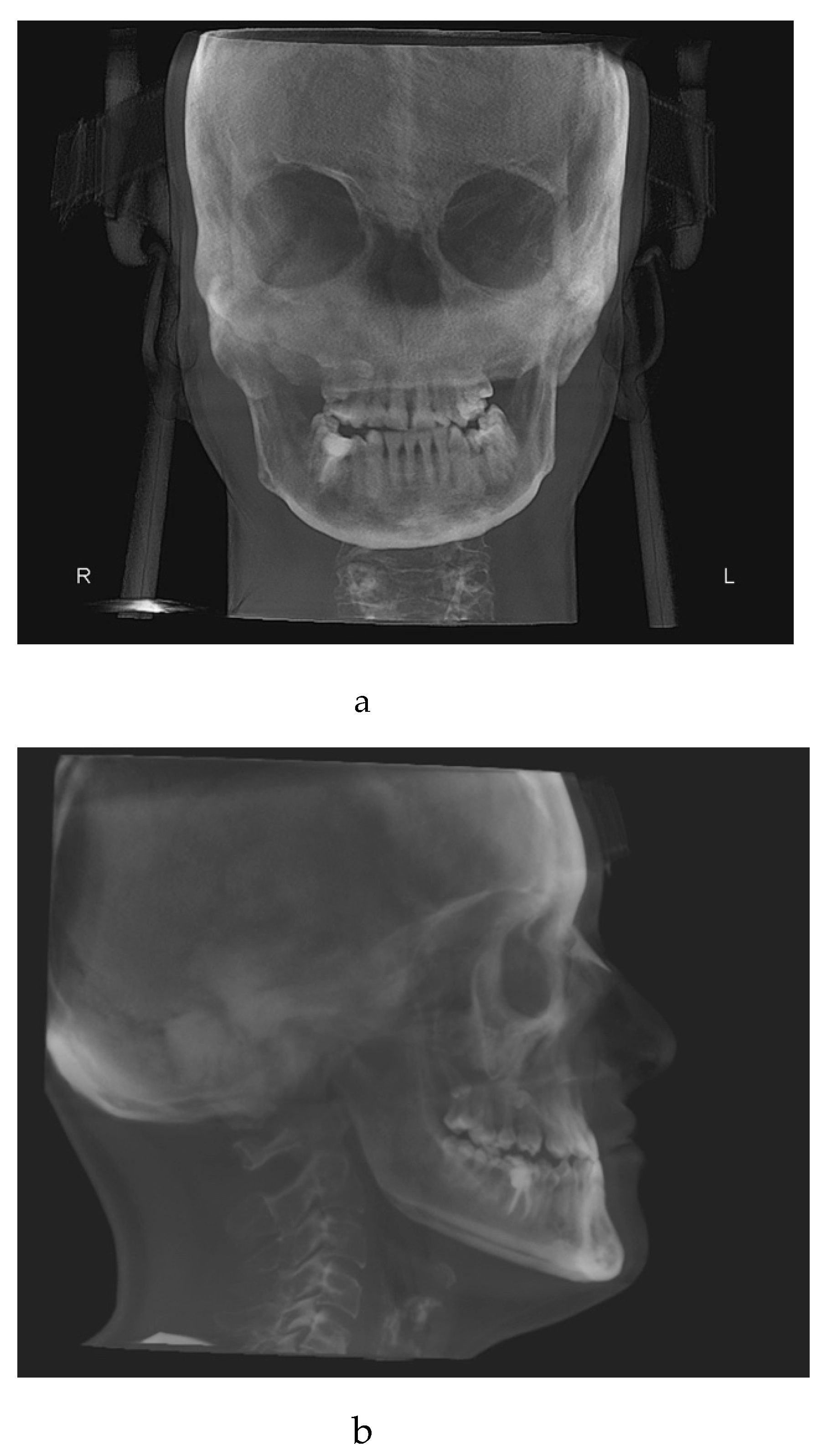

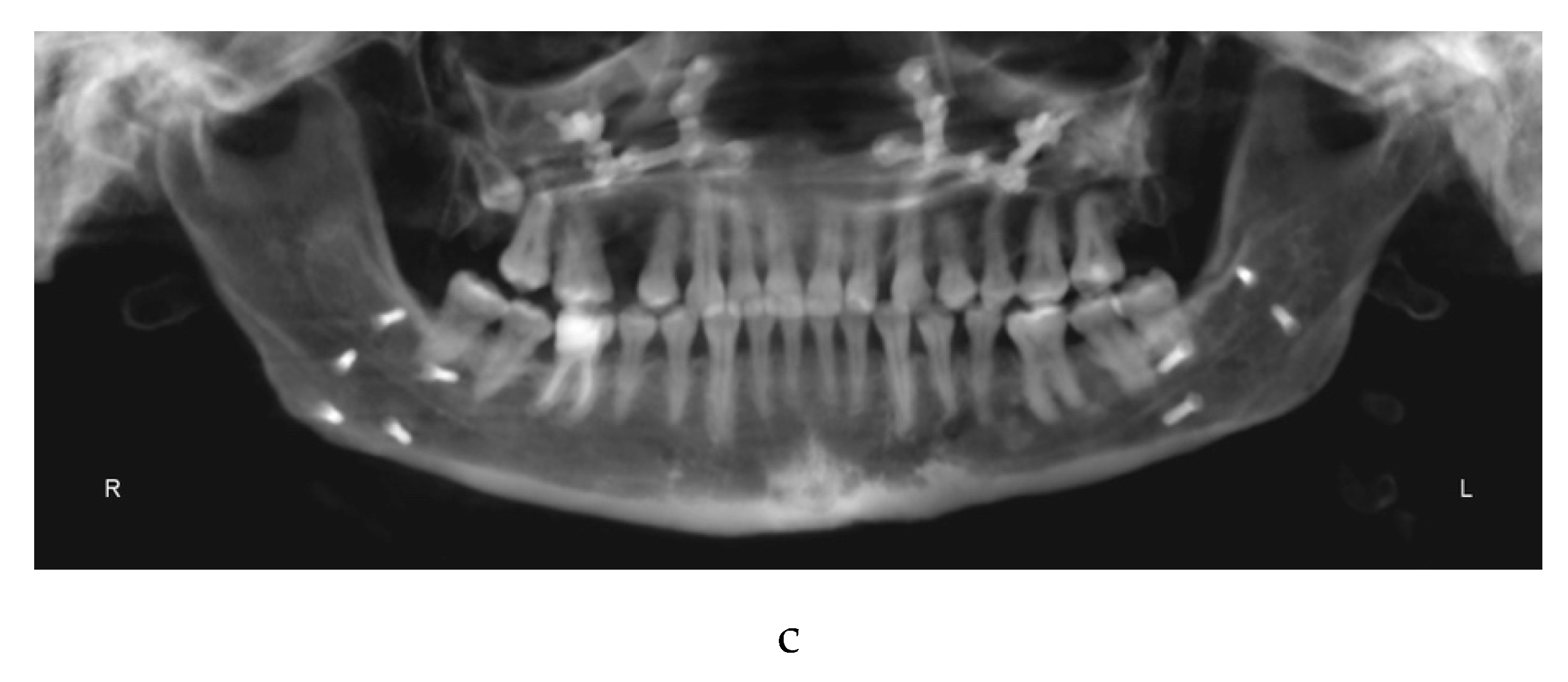

2.3. Radiographic Assessment

The x-ray examination through cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) [

22] (

Figure 1a, 1b, 1c) processed with dolphin software [

23] showed:

- Third skeletal class

- Hyperdivergent skeletal profile

- Left lateral deviation of the mandible

- Contracted upper arch

- Inclusion of 15 in a transverse position, near the apexes of elements 1.4 and 1.6.

2.4. Treatment Plan

The treatment plan involved a presurgical orthodontic phase. The aim was to align and level the arches, removing the dental compensations of the third-class malocclusion [

24] (upper incisors proclination and lingual inclination of the lower incisors), mesializing and derotating element 1.4. This phase included the avulsion of the impacted 1.5. [

25].

Afterwards the orthognathic surgery was necessary to obtain anterior and posterior maxillary alignment and to resolve the anterior crossbite and the right and left posterior crossbite [

26].

After surgery, the patient underwent post-surgical orthodontic treatment, to refine the alignment and avoid surgical relapse [

27].

3. Results

3.1. Treatment and Follow-Up

The patient underwent the orthodontic examination in April 2016 and received the diagnosis and the treatment plan in May 2016.

The therapy started in June 2016 with multibracket self-ligating attachments for the upper jaw, Damon prescription, followed by the same approach for the lower jaw in September 2016.

In this syndromic patient, the self-ligating technique proved to be very useful and valid because the check-up and follow-up appointments’ duration was significantly reduced. In fact, the patient was sufficiently cooperative, but she quickly got tired during the sessions.

The pre-surgical orthodontic treatment lasted 3 years. The duration was slightly longer than average [

28] but considering the medical condition of the patient we believe that the times were appropriate. She missed various check-up appointments because of some ocular problems she was dealing with during the treatment period. Furthermore, several times we had to stop to manage periodontal inflammation and newly motivate the patient to proper oral hygiene. Then on two occasions the patient lost motivation and she was not completely cooperative for several months. The patient was also treated by a psychologist team for the entire duration of the treatment.

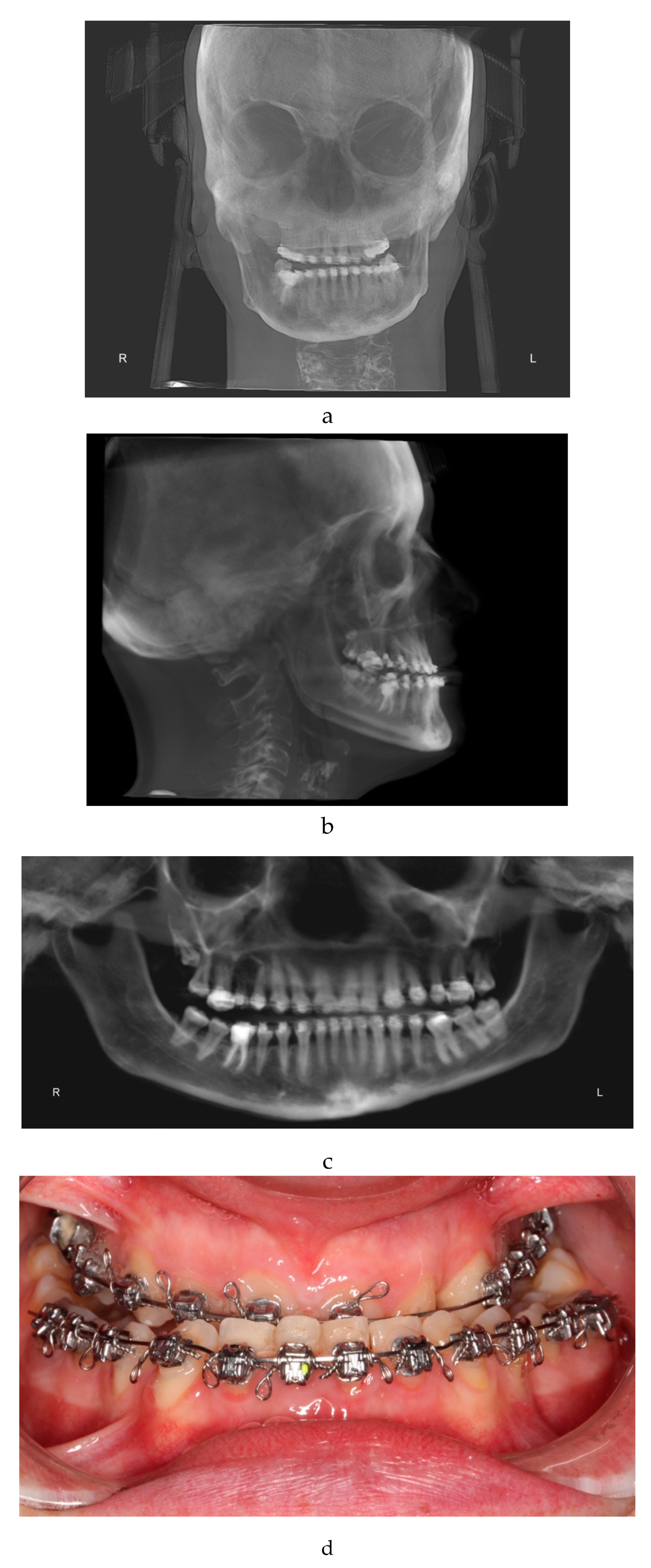

In June 2019, the objectives of the pre-surgical orthodontic treatment were considerably achieved: the arches were leveled, the teeth aligned, and the dental compensations of the third skeletal class had been removed. The pre-surgical diagnostic records were sent (

Figure 2a–d) to the maxillofacial equip. Kobayashi ligatures were placed all over the teeth to prepare the patient for surgery.

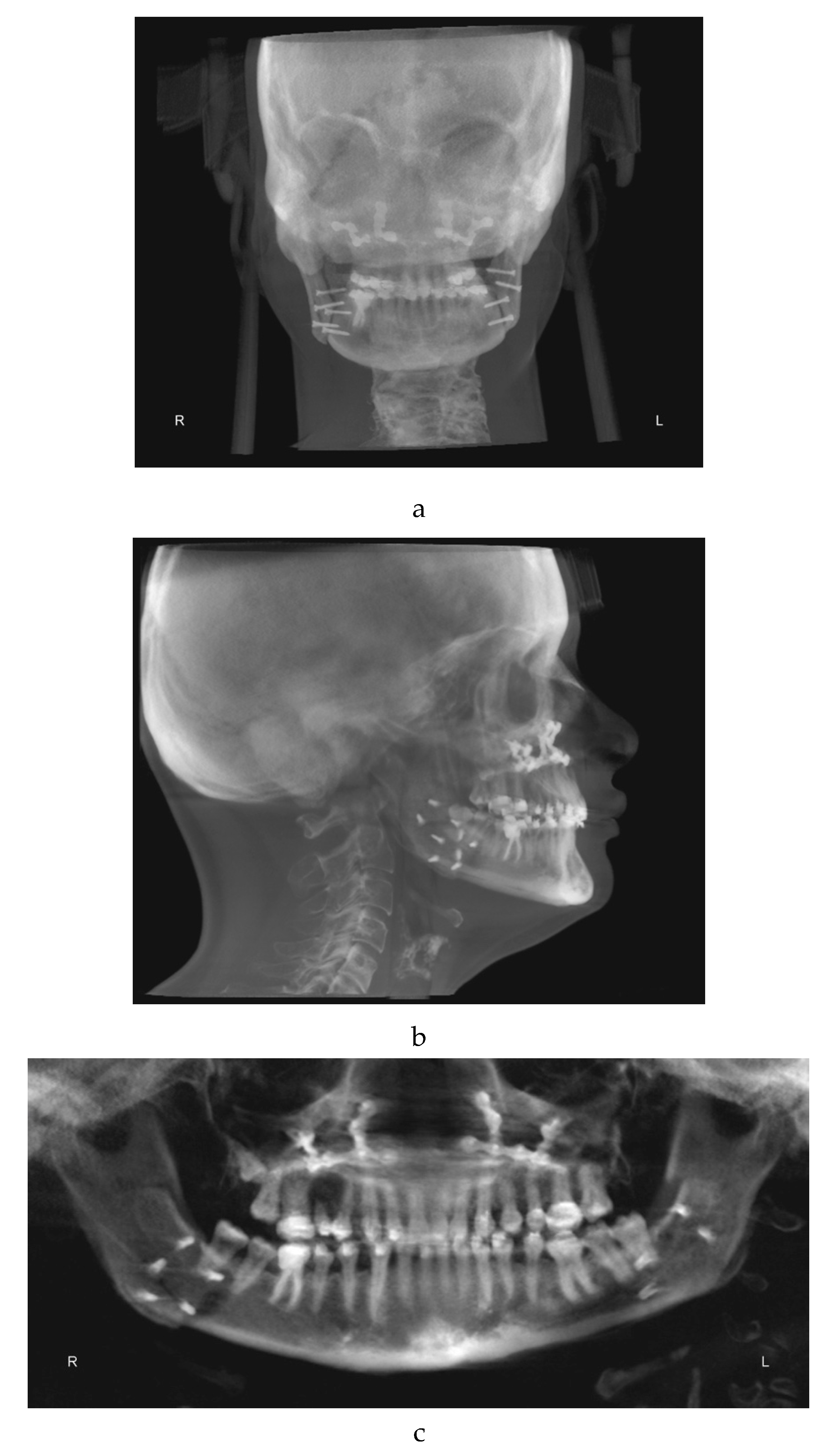

In October 2019 the patient underwent maxillofacial surgery to correct the severe skeletal malocclusion and relocate the bone bases in the right relationship. The combined surgery involved maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy [

29]and mandibular reduction [

30]. Skeletal fixation plates were then used to stabilize the bone segments [

31].

One week later the post-surgical orthodontic treatment phase started (

Figure 3a–c).

During the post-surgical orthodontic treatment frequent follow up examinations were performed to reduce the risk of relapse and to complete the alignment. In this phase, element 1.5 was extracted.

It was challenging to regain entirely the patient's collaboration after the surgery because she was scared and demotivated. Her family and therapy team worked for several months to get her to collaborate again. Unfortunately, during this phase a partial orthodontic relapse was recorded. In fact, the patient did not cooperate enough with the intermaxillary maintenance elastic bands. Furthermore, she had to be constantly re-motivated regarding home oral hygiene procedures.

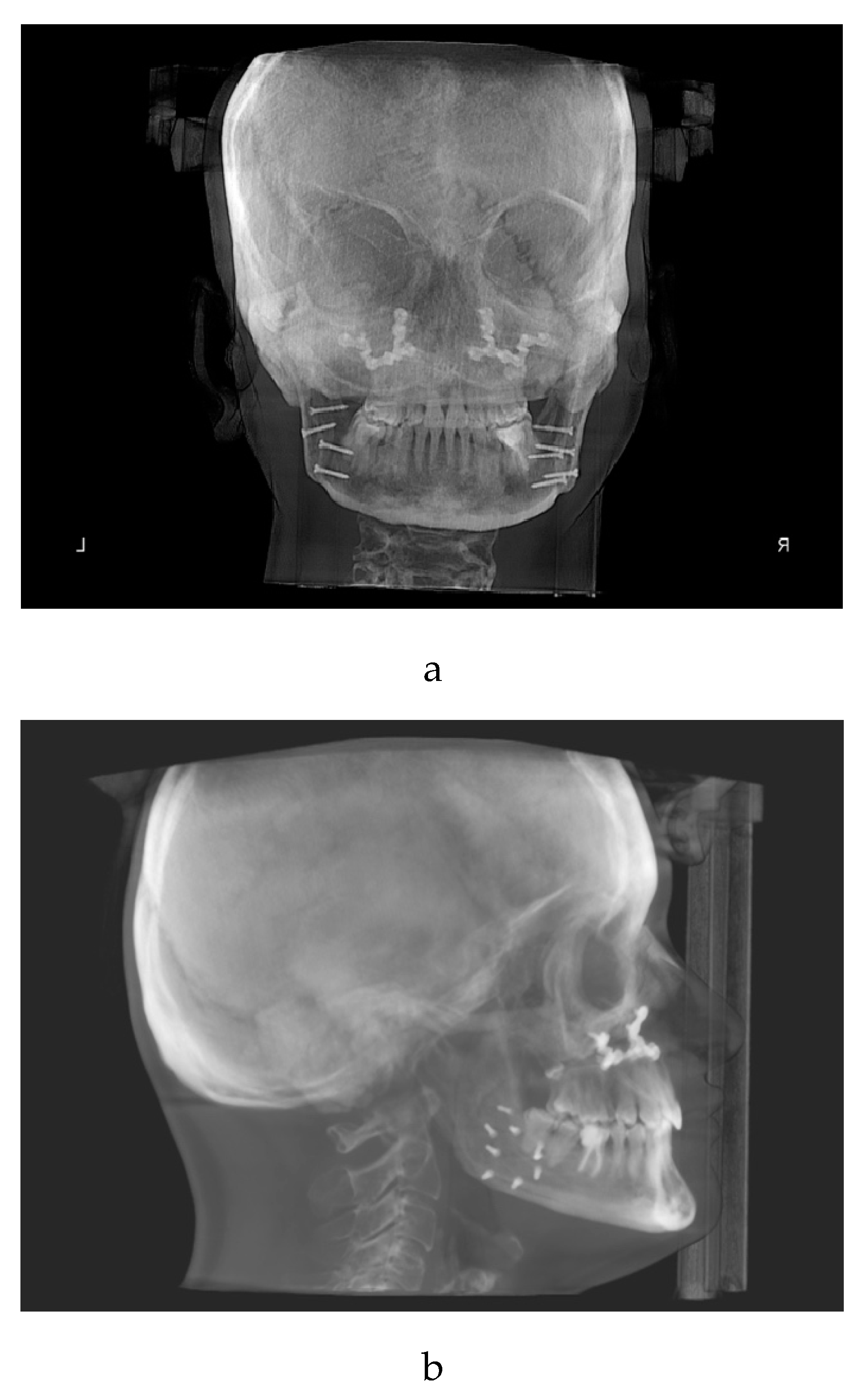

Since May 2021 the patient wore cross arch elastics on elements 1.6, 1.4, 2.6, 2.4, 2.5 to control the high tendency to relapse. (

Figure 4)

In August 2022, the post-surgical orthodontic treatment was considered finished as well as no risk of surgical relapse. We proceeded with the removal of the orthodontic appliances (

Figure 5a–c) and the delivery of the restraints.

4. Discussion

The patient with CSS underwent the first visit at the D'Annunzio orthodontics department in April 2016, at the age of 26.

Pre-surgical orthodontic treatment lasted 3 years as well as the post-surgical orthodontic one.

During the pre-surgical orthodontic treatment, the arches were aligned and leveled, and the dental decompensation was solved. During this phase a slowdown occurred because the patient had difficulty to understand the purpose of the "worsening of the malocclusion". She therefore tended to skip appointments. After the surgery, the post-operative pain was worsened and complicated by poor oral hygiene, resulting in a further slowdown and unfortunately also a beginning of relapse of the transverse dimension of the upper jaw.

In a rare case report of a patient with CSS of Dr Sahil Mustafa Kidwai et al.l., a 20yo female underwent oral and extraoral examinations. Intraoral examination revealed missing maxillary lateral incisor, generalized periodontitis and bifid uvula. The patient had poor oral hygiene and was never cooperative in preserving her oral health. The author found that early professional treatment and daily care at home can mitigate the severity and frequency of oral health issues. [

32]

Anyway, despite the ID our patient was cooperative and allowed the operators to perform all the necessary surgical and orthodontic treatment. The duration of the therapy was influenced by the patient's poor oral hygiene, which required a considerably number of pauses for adequate oral hygiene procedures and motivation. Furthermore, the patient missed numerous follow-up appointments because of the comorbidities of CSS, ocular and dermatological conditions.

Despite this, the operators were satisfied with the result since the treatment allowed the patient to improve her aesthetic appearance and functional abilities. Furthermore, the patient's parents were impressed to note that their daughter's socialization skills were also improved after the treatment.

Both the family and the psychologists preserved and maintained the patient's collaboration throughout the treatment leveraging the aesthetic result of the therapy and the resolution of the jaw deviation. In fact, despite her ID, the patient was perfectly conscious of her syndromic situation and of the functional and aesthetic limitation of her malocclusion.

The outcome cannot be considered perfect since the patient did not want to rehabilitate element 1.5 after the treatment, and a small component of lateral mandibular deviation remained. Moreover, there was a recurrence of the maxillary expansion because the patient lacks cooperation for several months after surgery. However, negligible failures considering the starting condition and the patient's health condition.

The operators continue to visit the patient every year.

5. Conclusions

It has been interesting for us to describe this case because we think that patients with CSS can be treated with a customized approach and treatment plan.

The treatment lasted longer than average and did not lead to a perfect outcome, but nevertheless the patient responded well to the most of steps and cooperated at the best of her ability.

Clearly the patient's collaboration had to be constantly supervised and re-motivated by her family and all the professional figures who revolve around her. It was a challenging, long and intense work also from a psychological standpoint.

Today the patient no longer has the anterior crossbite, a slight left posterior crossbite persists. Moreover, she has an aesthetically acceptable smile and less concerns about her social life. She is extremely pleased with her new smile and her family reports that after the treatment they noticed an improvement in socializing with her peers.

We think that this is of enormous importance, especially in patients with multiple disabilities and comorbidities.

In conclusion, we wanted to document this case, although the result is not “orthodontically” perfect and ultimate, to support and send the message that even syndromic patients can be treated if comorbidities and collaboration allow it. The need of more, support and collaboration with the family and psychotherapists must be considered, but clinical cases like this can be faced and solved. Obviously, each syndromic patient is a unique case, and the risk-benefit ratio must be correctly assessed for each one.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and F.F; methodology, M.M.; validation, M.M., C.R., M.F. and C.D.; formal analysis, M.M C.R.; resources, M.M. and F.F.; data curation, C.R., M.M. and C.D.; writing, M.M., C.R and C.D.; writing—review and editing, M.M.; supervision, M.M. and F.F;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval (number 23) was obtained by Independent Ethics Committee of Chieti hospital. The study protocol was drawn following the European Union Good Practice Rules and the Helsinki Declaration. Patient provided written informed consent before the beginning of orthodontic and surgical therapies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the subject involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, L. ARID2, a Rare Cause of Coffin-Siris Syndrome: A Clinical Description of Two Cases. Front Pediatr. 2022, 23; 10:911954. [CrossRef]

- Vergano, S. S., Santen, G., Wieczorek, D., Wollnik, B., Matsumoto, N., & Deardorff, M. A. Coffin-siris syndrome. GeneReviews®[Internet]. 2021.

- Miyake, N.; Tsurusaki, Y.; Matsumoto, N. Numerous BAF complex genes are mutated in Coffin-Siris syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014, 166C(3):257-61. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31406.

- Kosho, T.; Miyake, N.; Carey, J.C. Coffin-Siris syndrome and related disorders involving components of the BAF (mSWI/SNF) complex: historical review and recent advances using next generation sequencing. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014, 166C(3):241-51.

- Vasko, A.; Drivas, T.G.; Schrier Vergano, S.A. Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in 208 Individuals with Coffin-Siris Syndrome. Genes (Basel). 2021, 19;12(6):937. [CrossRef]

- Fleck, B.J.; Pandya, A.; Vanner, L.; Kerkering, K.; Bodurtha, J. Coffin-Siris syndrome: review and presentation of new cases from a questionnaire study. Am J Med Genet. 2001, 15;99(1):1.

- Ozkan, A.S.; Akbas, S.; Yalin, M.R.; Ozdemir, E.; Koylu, Z. Successful difficult airway management of a child with Coffin-siris syndrome. Clin Case Rep. 2017, 29;5(8):1312-1314. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Bielsa, A., Ruiz-de-Larramendiz, D. R., Abenia-Usón, P., Gracia-Cazaña, T., & Gilaberte, Y. (2024). Nail dysplasia and digital hypoplasia‒Coffin-Siris syndrome. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia.

- Vergano, S. S., Santen, G., Wieczorek, D., Wollnik, B., Matsumoto, N., & Deardorff, M. A. Coffin-Siris Syndrome Synonym: Fifth Digit Syndrome.

- Vergano, S. S., Santen, G., Wieczorek, D., Wollnik, B., Matsumoto, N., & Deardorff, M. A. Coffin-Siris Syndrome Synonym: Fifth Digit Syndrome.

- Hoyer, J.; Ekici, A.B.; Endele, S.; Popp, B.; Zweier, C.; Wiesener, A.; Wohlleber, E.; Dufke, A.; Rossier, E.; Petsch, C.; Zweier, M.; Gohring, I.; Zink, A. M.; Rappold, G.; Schrock, E.; Wieczorek, D.; Riess, O.; Engels, H.; Rauch, A.; Reis, A. Haploinsufficiency of ARID1B, a member of the SWI/SNF-a chromatin-remodeling complex, is a frequent cause of intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2012, 90:565–72.

- Fleck, B. J.; Pandya, A.; Vanner, L.; Kerkering, K.; Bodurtha, J. Coffin-Siris syndrome: review and presentation of new cases from a questionnaire study. Am J Med Genet. 2001, 99:1–7.

- Kosho, T.; Okamoto, N. Genotype-phenotype correlation of Coffin-Siris syndrome caused by mutations in SMARCB1, SMARCA4, SMARCE1, and ARID1A. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014, 166C:262–75.

- Santen, G. W.; Clayton-Smith, J. The ARID1B phenotype: what we have learned so far. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014, 166C:276–89. [CrossRef]

- Vergano, S. S.; Santen, G.; Wieczorek, D.; Wollnik, B.; Matsumoto, N.; Deardorff, M. A. Coffin-Siris Syndrome Synonym: Fifth Digit Syndrome.

- Kosho, T.; Okamoto, N.; Ohashi, H.; Tsurusaki, Y.; Imai, Y.; Hibi-Ko, Y.; Kawame, H.; Homma, T.; Tanabe, S.; Kato, M.; Hiraki, Y.; Yamagata, T.; Yano, S.; Sakazume, S.; Ishii, T.; Nagai, T.; Ohta, T.; Niikawa, N.; Mizuno, S.; Kaname, T.; Naritomi, K.; Narumi, Y.; Wakui, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Miyatake, S.; Mizuguchi, T.; Saitsu, H.; Miyake, N.; Matsumoto, N. Clinical correlations of mutations affecting six components of the SWI/SNF complex: detailed description of 21 patients and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2013, 161A(6):1221-37. [CrossRef]

- Schrier, S. A.; Bodurtha, J. N.; Burton, B.; Chudley, A. E.; Chiong, M. A. D.; D'avanzo, M. G.; ... & Deardorff, M. A. The Coffin–Siris syndrome: a proposed diagnostic approach and assessment of 15 overlapping cases. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 2012, 158(8), 1865-1876.

- Figueira, H. S.; Medina, P. O.; de Jesus, G. P.; Hanan, A. R. A.; Júnior, E. C. S.; Hanan, S. Oral findings in Coffin-Siris syndrome: A case report. Rev Port Estomatol Med Dent Cir Maxilofac, 2021, 62, 42-9.

- Ozkan, A. S.; Akbas, S.; Yalin, M. R.; Ozdemir, E.; Koylu, Z. Successful difficult airway management of a child with Coffin-siris syndrome. Clinical Case Reports, 2017, 5(8), 1312.

- Figueira, H. S.; Medina, P. O.; de Jesus, G. P.; Hanan, A. R. A.; Júnior, E. C. S.; Hanan, S. Oral findings in Coffin-Siris syndrome: A case report. Rev Port Estomatol Med Dent Cir Maxilofac, 2021, 62, 42-9.

- Nouri, M.; Hamidiaval, S.; Akbarzadeh Baghban, A.; Basafa, M.; Fahim, M. Efficacy of a Newly Designed Cephalometric Analysis Software for McNamara Analysis in Comparison with Dolphin Software. J Dent (Tehran). 2015, 12(1):60-9.

- Feragalli, B.; Rampado, O.; Abate, C.; Macrì, M.; Festa, F.; Stromei, F.; Caputi, S.; Guglielmi, G. Cone beam computed tomography for dental and maxillofacial imaging: technique improvement and low-dose protocols. Radiol Med. 2017, 122(8):581-588. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M.; Hamidiaval, S.; Akbarzadeh Baghban, A.; Basafa, M.; Fahim, M. Efficacy of a Newly DesignedCephalometricAnalysis Software for McNamara Analysis in Comparison with Dolphin Software. J Dent (Tehran). 2015, 12(1):60-9.

- Alhammadi, M. S.; Almashraqi, A. A.; Khadhi, A. H.; Arishi, K. A.; Alamir, A. A.; Beleges, E. M.; Halboub, E. Orthodontic camouflage versus orthodontic-orthognathic surgical treatment in borderline class III malocclusion: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig. 2022, 26(11):6443-6455. [CrossRef]

- Macrì, M.; D’Albis, G.; D’Albis, V.; Timeo, S.; Festa, F. Augmented Reality-Assisted Surgical Exposure of an Impacted Tooth: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11097. [CrossRef]

- Proffit, W. R.; Turvey, T. A.; Phillips, C. Orthognathic surgery: a hierarchy of stability. The International journal of adult orthodontics and orthognathic surgery, 1996, 11(3), 191-204.

- Wolford, L. M. Comprehensive post orthognathic surgery orthodontics: complications, misconceptions, and management. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics, 2020, 32(1), 135-151.

- Wolford, L. M. Comprehensive post orthognathic surgery orthodontics: complications, misconceptions, and management. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics, 2020, 32(1), 135-151.

- Sullivan, S. M. Le Fort I Osteotomy. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am, 2016, 24(1), 1-13.

- Chan, T. C.; Harrigan, R. A.; Ufberg, J.; Vilke, G. M. Mandibular reduction. The Journal of emergency medicine, 2008, 34(4), 435-440.

- Ellis III, E. Rigid skeletal fixation of fractures. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 1993, 51(2), 163-173., A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196.

- Mustafa, S.; Ahmed, R.; Goel, S.; Atif, A. Coffin Siris Syndrome: A Rare Case Report.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).