1. Introduction

Hyperspectral image (HSI) classification has become an essential research area in remote sensing due to its capability to capture rich spectral information [

1,

2,

3]. Traditional methods for hyperspectral image classification face various limitations and drawbacks. A widely used method includes linear discrimination analysis (LDA) [

4,

5], K Nearest Neighbors [

6,

7], Naive Bayes [

8,

9], polynomial logic regression classification [

10,

12], support vector machine [

13,

14,

15], and others. These methods generally rely on statistical principles and typically represent models within a vector space. A data matrix often describes geographical spatiotemporal datasets, where each sample is considered a vector or point within a finite-dimensional Euclidean space. The interrelationships among samples are defined by the connections between points [

16,

17]. Another category of classification methods focuses on spectral graph features. These methods transform spectral data into spectral curves and then perform direct classification and analysis based on the spectral curve graph features [

18,

19]. Techniques such as the cumulative cross-area of spectral curves, fractal feature method [

20], spectral curve feature point extraction method [

21], spectral angle classification [

22], spectral curve matching algorithm [

23], and spectral curve graph index method that describes key statistical features [

24] are included. Overall, these approaches mainly focus on the global morphological information of the spectral curve and lack a comprehensive understanding of the spatial structural characteristics inherent in the spectral information [

25,

27]. Effective extraction of spectral curves or features and optimizing model design are critical research areas for enhancing image classification accuracy.

Deep learning, a machine learning approach based on artificial neural networks, traces its origins to the perceptual machine model of the 1950s [

28]. Research has demonstrated the promising potential of deep learning methods in classifying graphics [

29]. In recent decades, significant efforts have been dedicated to extensively studying and enhancing neural networks. The increased prevalence of deep learning can be attributed to advancements in computing power, the availability of vast datasets, and the algorithms' continuous evolution [

30]. Due to limitations in computing resources and imperfect training algorithms, neural networks have faced challenges in practical applications. In 2006, Geoffrey Hinton introduced the Deep Belief Network (DBN), which spearheaded a new wave in deep learning [

31,

32]. The DBN employs greedy pre-training to iteratively extract abstract data features through multi-layer unsupervised learning. Recently, researchers have increasingly utilized deeper network structures combined with the backpropagation algorithm. Deep neural networks have significantly advanced image classification, voice recognition, and natural language processing [

33,

35]. In 2012, Krizhevsky introduced the Alexnet convolutional neural network model, which secured victory in the ImageNet image classification competition, effectively indicating the immense potential of deep neural networks in handling large-scale complex data [

33]. Subsequently, many deep learning models have emerged, such as the VGG [

36,

37] network models proposed by Simonyan and Zisserman in 2014 and the GoogLeNet [

38] introduced by Google. In 2015, Kaiming presented the ResNet neural network model, which introduced residual connections to address the issues of gradient vanishing and explosion in deep neural networks [

39]. Since then, numerous subsequent studies have been conducted, such as ResNetV2 [

40], ResNetXT [

41], and ResNetST [

42], which have further enhanced the performance of the model. The ongoing refinement of deep learning models has led to significant advancements in image classification, resulting in a continuous enhancement of the accuracy of image classification results. These developments have provided a wealth of well-established classification model frameworks for future researchers. The models above primarily rely on 2D-CNN, in addition to numerous classification methods based on sequential data, such as Multi-layer perception machine (MLP), 1D-CNN [

43], RNN [

44], and HybridSN [

45], and 3D-CNN [

46,

47] classification methods that incorporate attention mechanisms [

48,

49]. The MLP is a fundamental feedforward neural network structure for processing various data types, possessing strong fitting and generalization capabilities. 1D-CNN is commonly used for processing sequential data such as time series or sensor data. It effectively captures local patterns and dependencies within the data, making it suitable for speech recognition and natural language processing [

43]. RNN is designed to handle sequential data by maintaining an internal memory that allows it to process input sequences of arbitrary length [

44]. This feature makes it well-suited for tasks involving sequential dependencies, such as language modeling, machine translation, and time series prediction. A hybrid spectral-spatial CNN (HybridSN) employs a 3D-CNN to learn the joint spatial-spectral feature representation, followed by encoding spatial features using a 2D-CNN [

45]. Extending the concept of traditional 2D-CNN, 3D-CNN processes spatio-temporal data such as videos, volumetric medical images, and high spectral data for classification [

50]. By considering both spatial and temporal features, 3D-CNNs effectively capture complex patterns and movements within the data, making them suitable for action recognition, video analysis, and medical image classification. These diverse classification methods are widely used for hyperspectral image classification.

Most high spectral deep learning classification methods currently rely on pixel block classification. This approach involves selecting central pixels and their surrounding pixels as the objects for classification. However, two major shortcomings persist: firstly, the model training only incorporates the pixel label value at the center of the image block, resulting in the wastage of a large amount of label information from the neighborhood and the disregard of spatial information within the pixel block; secondly, overlapping can lead to severe information leakage [

51,

52]. When using pixel patches as training features, pixel blocks containing label information are directly or indirectly utilized for model training. However, these methods cannot generally be generalized to untagged data. In order to address these issues, this study introduces a new method for pixel-based HSI classification, undertaking the following tasks:

(1) The eigenvalues of each band of the hyperspectral image are transformed into polarization feature maps utilizing the polar coordinate conversion method. This process converts each pixel's spectral value into a polygon, capturing all original pixel information. These transformed feature maps then serve as a novel input form, facilitating direct training and classification within a classic 2D-CNN deep learning network model, such as VGG or ResNet.

(2) Based on the feature maps generated in the previous step, a novel deep learning residual network model called DCFF-Net is introduced for training and classifying the converted spectral feature maps. This study includes comprehensive testing and validation across three hyperspectral datasets: Indian Pines, Pavia University, and Salinas. The proposed model consistently exhibits superior classification performance across these datasets through comparative analysis with other advanced pixel-based classification methods.

(3) The response mechanism of DCFF-Net's classification accuracy to polar coordinate maps under different filling methods is analyzed. The DCFF-Net model, evaluated using pixel-patch input mode, is compared to other advanced models for classification performance, consistently demonstrating outstanding results.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Experimental Datasets and Implementation

The Indian Pines (IP) Aerial hyperspectral dataset, collected by the AVIRIS sensor on June 12, 1992, encompasses an area of 2.9 km × 2.9 km in northwest Indiana. The dataset features a pixel size of 145 × 145 (21025 pixels), a spatial resolution of 20 m, a spectral range from 0.4 to 2.5 µm, and includes 16 land cover types, predominantly in agricultural regions. Originally comprising 220 bands, the dataset was refined to 200 bands after excluding 20 bands that captured atmospheric water absorption and exhibited low SNR. The retained data from these 200 bands were utilized in this experiment.

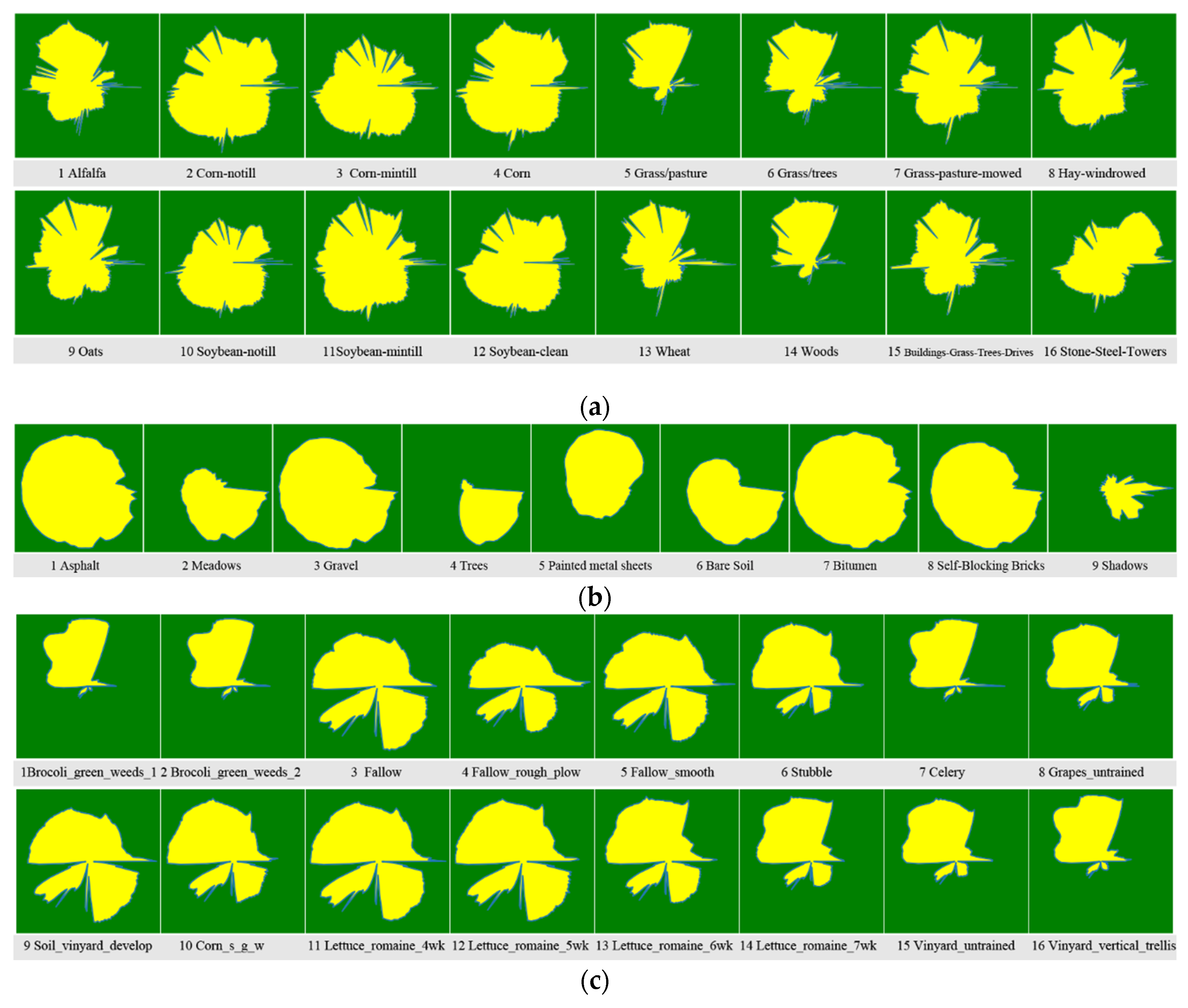

Table 1 and

Figure 3 (a) (b) illustrate the actual marking information of ground objects in this dataset. The sample distribution across different types is highly variable, with quantities ranging from 20 to 2455.

Aerial hyperspectral remote sensing images of Pavia University (PU) were obtained by the German airborne Reflective Optical Spectral Imager (ROSIS) on July 8, 2002, in the campus area of the University of Pavia, Italy. The spatial resolution of the data is 1.3 m, the image size is 610 x 340 pixels (207,400 pixels), and the spectral range of the image spans from 0.43 to 0.86 µm, encompassing 115 spectral channels. The dataset includes nine urban land cover types and 42,776 labeled pixels. The image on the right displays a false-color composite image of the Pavia University data and the actual overlay type of the surface. Due to noise, 12 noise bands were eliminated, leaving 103 bands to verify the performance of the proposed method. The PU dataset contains nine categories of ground objects, as shown in

Figure 3 (c) (d).

The Salinas dataset (SA) consists of hyperspectral remote sensing images of the Salinas Valley region in southern California, United States, acquired by the AVIRIS sensor. The image measures 512 x 217 pixels, with a spatial resolution of 3.7 m, a spectral resolution between 9.7 and 12 nm, and a spectral range from 400 to 2500 nm. It includes 16 types of ground objects and 54,129 labeled samples. The dataset initially had 224 bands, but 20 bands affected by atmospheric water absorption and low signal-to-noise ratios were removed. The remaining 204 bands, retained after processing, are utilized in this experiment, as indicated in

Figure 3 (e) (f).

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Hyperspectral dataset: Indian pines (a)(b), Pavia University (c)(d), Salinas(e)(f)

Figure 3.

Figure 3. Hyperspectral dataset: Indian pines (a)(b), Pavia University (c)(d), Salinas(e)(f)

All experiments were conducted in identical environments using two computers. The configuration for these computers was as follows: the hardware platform included an Intel Core i7-9700K (8 cores/8 threading)/i7-1100F (8 cores/16 threading) processor with 12M/16M L3-cache/, 64GB/128G DDR4 memory at 3200MHz serial speed, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2070 GPU with 8GB DDR5/RTX 3060 GPU with 12GB DDR5 video memory, and a 1TB HDD with 7200 RPM. The software platform comprised the Windows 10 Professional operating system, Keras 2.5.0 based on TensorFlow-gpu 2.5.0, and Python 3.7.7. Models were trained using a batch size of 12, with IP models employing an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 2×10−3, a decay of 1×10−4, and PU&SA models using a learning rate of 1×10−4 and a decay of 1×10−5.

3.2. Evaluation Criterion

Classification accuracy was estimated using evaluation indicators such as overall accuracy (OA), average accuracy (AA) for each category, user accuracy (UA) for each category, and kappa coefficient (KA) [

1,

56]. In this text, percentages represent the KA. The calculation formula is as follows:

where

is the class

;

(True Positive) is the number of true examples, i.e., the number of samples that are correctly classified as positive examples;

(True Negative) is the number of true counterexamples, i.e., the number of samples that are correctly classified as negative examples;

(False Positive) is the number of false positives. The number of examples, i.e., the number of samples that are incorrectly classified as positive examples;

(False Negative) is the number of false counterexamples, that is, the number of samples that are incorrectly classified as negative examples.

is the total number of categories.

is the accuracy of the classifier;

is the random accuracy that the classifier can achieve.

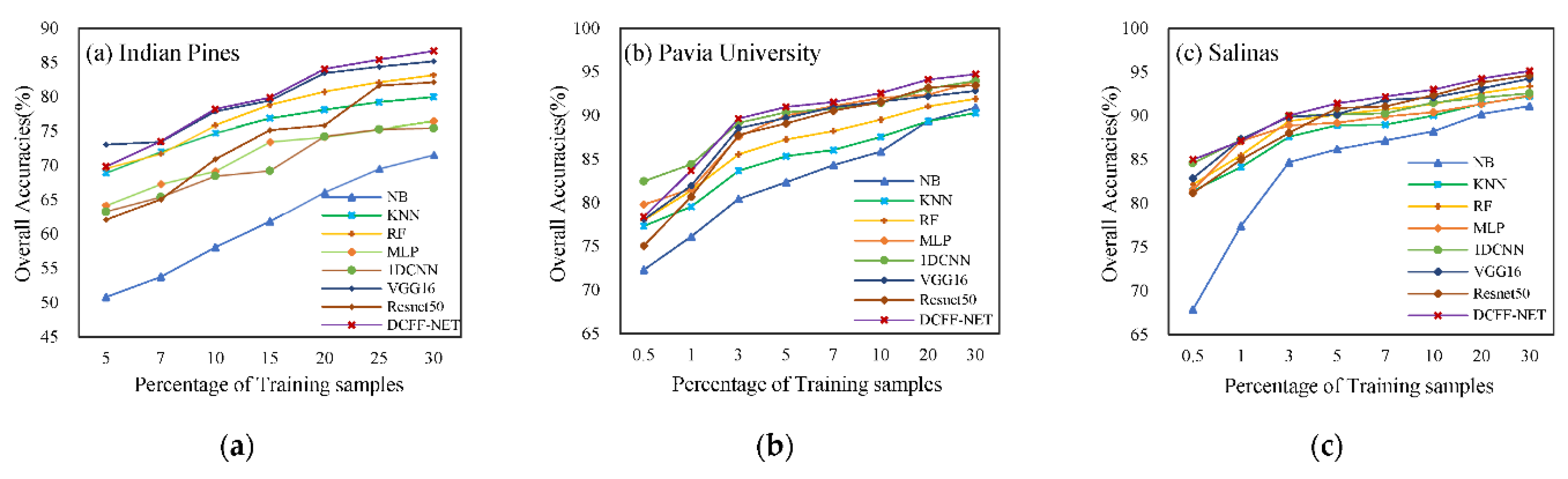

3.3. Results Analysis Based on Feature Map

Traditional Naive Bayes (NB), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), 1D-CNN, VGG16, and ResNet50 deep learning methods were selected for comparative analysis with DCFF-NET. NB, KNN, and RF are all open-source machine learning libraries in Python. The data partitioning for random seeds was set to fixed values to achieve data recovery. NB, KNN, and RF use automatic searches (Grid Search) to select the optimal parameters with a 50% off verification method. MLP, 1D-CNN, VGG16, ResNet50, and DCFF-Net methods were implemented using TensorFlow2.5.0, and a grid search algorithm was also employed to obtain optimal parameters. When using a grid search method, important parameter selection was performed first, reducing the parameter space range and gradually narrowing the search range of the parameters based on the calculation results to improve search efficiency. This study uses different proportions of training samples for training and prediction. As the proportion of the training sample changes, the training process and performance of the model are also affected. Therefore, under different training sample proportions, the best parameter combination is sought to ensure the best performance and generalization ability of the model. The best parameters and optimal models were selected to predict and evaluate the three hyperspectral datasets. The results are depicted in

Table 2.

When various classification methods use different training sample ratios, the accuracy of image prediction results increases significantly as the proportion of training samples increases. The DCFF-Net classification method performs well on the three datasets. The three different datasets exhibit higher performance than the lower training ratios in the case of 10%, 20%, and 30% training ratios. Except for the maximum value of AA, all other values achieve the maximum value and demonstrate the best classification performance overall. With 30% training samples, the OA, KA, and AA of the IP datasets are 86.68%, 85.05%, and 85.08%; the OA, KA, and AA of the PU dataset are 94.73%, 92.99%, and 92.60%; and the OA, KA, and AA of the SA dataset are 95.14%, 94.59%, and 97.48%.

3.3.1. Results of Indian Pines

Figure 4 shows the classification result chart obtained using 30% of the training samples from the Indian Pines dataset. The UAs of each category in this dataset are listed in

Table 3. It can be observed from the table that out of the 16 land types, seven types achieve the best classification effects compared to other classification methods when using the DCFF-Net classification method. The OA, KA, and AA are 86.68%, 85.04%, and 85.08%, respectively, higher than other classification methods. The classification effect of VGG16 is less than that of DCFF-Net, with OA, KA, and AA at 85.18%, 83.16%, and 83.21%, respectively. Secondly, ResNet50 also performs well. These three deep learning methods outperform other classification methods. The optimal UA values for the 16 land types are scattered across various classification methods and are not concentrated in a specific classification method. In some categories, such as Corn-no Till, Corn, Oats, and others, DCFF-Net achieves a better classification effect. The NB classification methods show significant variation in UA across different categories. For Alfalfa, Grass-Pasture-Mowed, and Oats, the UA is 0.00% due to too few samples, while the highest, Hay-Windrowed, reaches an AA of 99.40%. However, the average accuracy across the 16 categories is only 53.85%, far lower than several other methods.

Figure 4.

Predicted classification map of 30% Samples for Training. (a) Three bands false color composite. (b) Ground truth data. (c) NB. (d) KNN. (e) RF. (f) MLP. (g) 1DCNN. (h) VGG16. (i) Resnet50. (j) DCFF-NET.

Figure 4.

Predicted classification map of 30% Samples for Training. (a) Three bands false color composite. (b) Ground truth data. (c) NB. (d) KNN. (e) RF. (f) MLP. (g) 1DCNN. (h) VGG16. (i) Resnet50. (j) DCFF-NET.

3.3.2. Results of Pavia University

Figure 5 illustrates the classification result diagram obtained using 30% training samples on the Pavia University dataset. The OA, KA, and AA of the DCFF-Net model are 94.73%, 92.99%, and 92.60%, respectively, and these three indicators have achieved the highest classification accuracy. Trees and Bitumen's UA are the highest compared to other methods. The 1D-CNN classification result's OA is second only to DCFF-Net, reaching 93.97%. The categories Gravel, Painted Metal Sheets, Bare Soil, and Shadows are higher than other methods. For Gravel and Bitumen, no classification methods have exceeded 90.00%. In

Figure 1, Gravel, Bitumen, and Self-Blocking Bricks have similar ground features, leading to generally low UA in these categories. Among all comparison methods, the KNN classification method has the lowest accuracy.

Figure 5.

Predicted classification map of 30% Samples for Training. (a) Three bands false color composite. (b) Ground truth data. (c) NB. (d) KNN. (e) RF. (f) MLP. (g) 1DCNN. (h) VGG16. (i) Resnet50. (j) DCFF-NET.

Figure 5.

Predicted classification map of 30% Samples for Training. (a) Three bands false color composite. (b) Ground truth data. (c) NB. (d) KNN. (e) RF. (f) MLP. (g) 1DCNN. (h) VGG16. (i) Resnet50. (j) DCFF-NET.

3.3.3. Results of Salinas

Figure 6 presents the classification result obtained using 30% training samples on the Salinas dataset. The number of training samples is 16,231.

Table 5 shows the user accuracy (UA) of various types in SA. DCFF-Net classification OA, KA, and AA are 95.14%, 94.59%, and 97.48%, respectively, better than other comparison methods. VGG16 and ResNet50 have also achieved better classification effects, second only to DCFF-Net. Among the 16 types of land, the DCFF-Net classification results are the highest in the UA of six places. Except for the low UA in Celery, the classification accuracy in other categories is not significantly different from other classification methods. The Celery UA is extremely low.

Figure 6 indicates that the characteristic graphic features of Celery and Broccoli_green_weeds_1 and Broccoli_green_weeds_2 are highly similar, making them difficult to distinguish effectively and significantly low accuracy. In the current classification methods, Grapes_untrained and Vineyard_untrained are difficult to distinguish. As shown in

Table 5, the three methods—DCFF-Net, VGG16, and ResNet50—are significantly higher than other classification methods. DCFF-Net significantly increases the characteristics of similar objects, obtaining higher classification accuracy. Grapes_untrained and Vineyard_untrained achieve 98.96% and 91.71%, respectively. In other methods, the UAs of Grapes_untrained and Vineyard_untrained are lower than 90.00%, with NB, KNN, RF, MLP, 1D-CNN, and other methods achieving less than 80.00%.

Figure 6.

Predicted classification map of 30% Samples for Training. (a) Three bands false color composite. (b) Ground truth data. (c) NB. (d) KNN. (e) RF. (f) MLP. (g) 1DCNN. (h) VGG16. (i) Resnet50. (j) DCFF-NET.

Figure 6.

Predicted classification map of 30% Samples for Training. (a) Three bands false color composite. (b) Ground truth data. (c) NB. (d) KNN. (e) RF. (f) MLP. (g) 1DCNN. (h) VGG16. (i) Resnet50. (j) DCFF-NET.

The eight classification methods mentioned in the text are NB, KNN, RF, MLP, 1D-CNN, VGG16, ResNet50, and DCFF-Net. The first five methods use one-dimensional serial vector data as the model input data, while the latter three are based on two-dimensional images. The latter three methods extract image features through 2D-CNN, classifying the data into different categories. In the IP data concentration, including Corn-Min Till, Corn, Oats, and Buildings-Grass-Trees-Drives, and on the SA dataset, including Grapes_untrained and Vineyard_untrained, the accuracy of the latter three methods is significantly higher than the first five methods. This indicates that 2D-CNN can achieve better classification effects in some easily mixed categories. However, for some categories, the first five methods perform better than the latter three methods, such as Soybean-Min Till, Woods, and Stone-Steel-Towers in the IP dataset. More suitable classification methods can be selected based on these observations in practical applications.

3.4. Results Analysis Based on Pixel-Patched

An additional evaluation was conducted using the pixel-patched method to examine the classification effectiveness of DCFF-NET and assess the performance of the proposed model. The methods NB, KNN, RF, MLP, and 1D-CNN use one-dimensional vector data and cannot directly use pixels as input data. Therefore, a comparative analysis was conducted using HybridSN, 3D-CNN, and A2S2KNet models. The pixel block size was uniformly extracted at 24 × 24 × S as the input data, where S is the number of image channels, and 10% of the categories were selected as training samples. The models underwent a fine-tuning process to facilitate the utilization of VGG16 and ResNet50 models for training and testing with the provided input data. After model training was completed, the optimal model was selected for testing, using 90% of the data as test data, performing the test 10 times. The average value and standard deviation were selected as the test results, as shown in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8. The OA and KA on the IP dataset were 98.15% and 97.89%, respectively, second only to A2S2K but higher than all other methods. The AA value of 97.73% was the highest of all methods. The OA, KA, and AA of 3D-CNN were the lowest, with values of 93.18%, 92.26%, and 94.52%, respectively. The DCFF-Net model achieved the best classification performance regarding OA, KA, and AA on the PU and SA datasets. The results on the two datasets were as follows: 99.86%, 99.82%, 99.79% and 99.98%, 99.98%, 99.94%, respectively. In addition, all comparison methods also achieved very high classification accuracy.

Figure 7.

Classification map of IP(A) PU(B)&SA(C) based on patched-based input. (a) False color composite. (b) Ground truth. (c) VGG16. (d) Resnet50. (e) 3-DCNN. (f) HybridSN. (g) A2S2K. (h) DCFF-NET.

Figure 7.

Classification map of IP(A) PU(B)&SA(C) based on patched-based input. (a) False color composite. (b) Ground truth. (c) VGG16. (d) Resnet50. (e) 3-DCNN. (f) HybridSN. (g) A2S2K. (h) DCFF-NET.

The pixel-patched block contains surrounding pixel information, specifically spectral-spatial information, which provides more discriminative cues for the target pixel. Using pixel-patched block data as the input for the model can effectively improve classification accuracy, as mentioned earlier, but it can also lead to potential label information leakage. In addition, the larger the pixel block, the more spatial information it contains; however, it will significantly increase computational complexity.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Chen Zhijie, Wang Yuan and Wang Xiaoyan; Funding acquisition, Wang Xinsheng; Investigation, Chen Zhijie; Methodology, Chen Zhijie, Chen Yu, Wang Yuan and Wang Xinsheng; Project administration, Wang Xinsheng; Software, Chen Zhijie and Chen Yu; Validation, Chen Zhijie, Chen Yu, Wang Yuan and Wang Xiaoyan; Visualization, Chen Zhijie, Chen Yu and Xiang Zhouru; Writing – original draft, Chen Zhijie, Chen Yu, Wang Yuan and Wang Xiaoyan; Writing – review & editing, Chen Zhijie, Chen Yu, Wang Yuan and Xiang Zhouru.