1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), chronic conditions necessitate ongoing management spanning years or even decades, encompassing a multifaceted range of health challenges that extend beyond the typical limits of chronic conditions [

1]. These conditions encompass not only disorders such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and bronchial asthma but also communicable conditions like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), which have transitioned from fatal to manageable conditions due to medical advancements. Concurrently, the spectrum of chronic conditions extends to mental health disorders such as major depressive disorder and schizophrenia, as well as defined disabilities, whether permanent or temporary, such as sensory impairments like blindness, musculoskeletal disorders, and rehabilitation needs following surgery or trauma. Even the oncological spectrum, addressed separately by the European Observatory, falls under this wide-ranging category [

2]. Despite variations in terminology, chronic conditions demand a comprehensive, holistic, and ongoing multidisciplinary approach, emphasizing collaboration among diverse healthcare professionals. Facilitating this approach mandates not only accessibility to essential pharmacotherapeutics and monitoring modalities but also the development of a healthcare conceptual framework that prioritizes patient empowerment.

The challenge of chronic diseases is further heightened by the lack of integrated data systems, which impairs research and multidisciplinary healthcare. Focusing too narrowly in clinical practice creates isolated approaches that can lead to inadequate collaboration, and limits development. In order to improve research and innovation, it is crucial to adopt a collaborative approach that incorporates knowledge from various specialties while valuing the unique perspectives on different diseases. Cross-disciplinary collaboration enhances efficiency and generates strong evidence to improve patient care [

3]. Given the primary focus of our paper on PCC, it is imperative to engage key care team members including patients, their families, healthcare providers, and institutions. A care team is a collection of healthcare professionals, such as physicians, nurses, specialists, therapists, and other healthcare providers, who work collaboratively to deliver complete patient care. This team-based approach ensures that all aspects of a patient's health are managed effectively, often involving the patient and their family as integral team members. According to Wagner et al., this concept emphasizes the importance of coordinated and collaborative care [

4]. It is further supported by reputable sources such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [

5]. Through collaborative efforts, these care team members contribute to designing a comprehensive framework of metrics developed to capture the core strategies of PCC.

PCC has become a central focus on healthcare quality, receiving significant attention and recognition for its crucial role in developing modern healthcare conceptual frameworks. It provides benefits such as increased patient satisfaction, trust, and improved communication alongside staff career advancement through positive feedback [

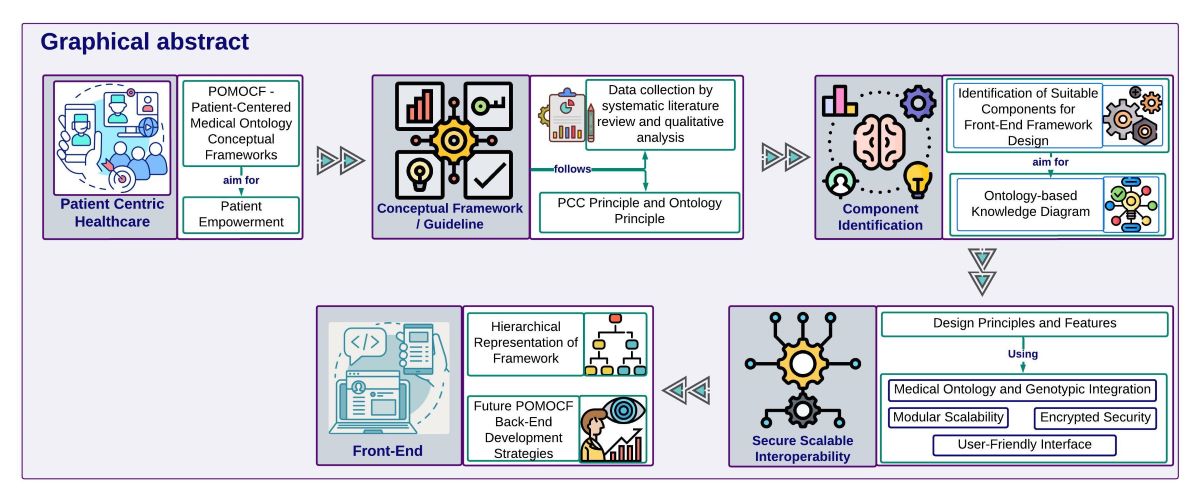

6]. PCC, a fundamental principle of modern healthcare, prioritizes patients’ active involvement and empowerment in their treatment and health management. This principle has gained significant attention and recognition for its vital function in developing modern healthcare conceptual frameworks. Innovative approaches like the POMOCF aim to revolutionize how patients interact with their EHRs by granting patients full authority over their personal and healthcare information. POMOCF transforms traditional data management practices, offering a streamlined and patient-centric approach to healthcare information access and utilization.

In the early 1990s, the healthcare industry shifted from paper-based to EHRs, driven by technological advancements and advocacy from the Institute of Medicine in the United States [

7]. As the inadequacies of paper records became evident, EHR adoption accelerated worldwide, with many countries embracing their transformative potential [

8]. In the United States, the implementation of EHRs has been guided by the Meaningful Use (MU) program. This initiative, launched in 2011, underwent three progressive stages of development to enhance healthcare delivery and patient outcomes [

9]. Over the past 25 years, EHR adoption among office-based physician practices has seen significant growth. According to Health IT data [

10], EHR adoption among office-based physician practices in the United States has risen from 18 percent in 2001 to 78 percent in 2013 for Any EHR, and from 72 percent in 2019 to 78 percent in 2021 for Certified EHR. This development underscores the ongoing efforts to enhance healthcare delivery through digital transformation.

In their seminal work, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) [

11] outlined Six Aims in

Crossing the Quality Chasm, aiming to enhance healthcare delivery by improving safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity. The integration of these aims into healthcare systems is essential to ensure high-quality care for patients with chronic conditions, while also tackling the challenges presented by fragmented data systems. Digital health solutions are necessary to properly manage chronic conditions and care, especially considering the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of long COVID cases. This global health crisis highlighted the unpreparedness of healthcare systems to manage surveillance on a mass scale and personalize surveillance effectively, underscoring the need for innovative technologies to navigate healthcare complexities and ensure continuity and quality of care [

12]. POMOCF can play a crucial role in addressing these challenges by providing a robust framework that supports comprehensive surveillance, data integration, and personalized care management. Empowering patients becomes vital during a health crisis, requiring user-friendly access to information and the necessary tools for informed decision-making. Our focus on PCC drives the development of a patient-centric front-end access conceptual framework. Empowering patients to manage their health information enhances engagement in care decision-making, advancing healthcare outcomes and aligning with the principles of PCC in information management.

EHRs play a pivotal role in simplifying healthcare by consolidating patient data into a centralized platform, thereby improving accessibility for healthcare providers and allowing patients to access their medical records directly. This direct access supports patients actively involved in their treatment and health management, resulting in empowerment and collaboration. Patient portals within EHR systems offer a range of features, including seamless access to medical records, secure communication with healthcare providers, appointment scheduling, and the ability to view test results and medication lists. These features enhance patient convenience and contribute to a more engaged and informed patient population, ultimately improving healthcare outcomes [

8,

13,

14]. Given the increasing prevalence of IoT devices and wearables, integrating these technologies into EHR systems represents a logical step toward improving patient care. This integration provides real-time health data for personalized interventions alongside challenges such as ensuring data security and managing interoperability. POMOCF can facilitate this integration, leading to more effective healthcare management for patients and providers.

The integration of chronic healthcare information and genomic data into EHRs is a significant breakthrough in healthcare. It aligns seamlessly with the PCC approach and targeted treatment initiatives. By combining information on chronic conditions with genomic insights, healthcare providers can comprehensively understand each patient's unique health profile and can create personalized treatment strategies that address individual needs. It also empowers patients to actively participate in their care, fostering a awareness of responsibility and independence regarding their health information. Moreover, it aids in the early identification of diseases and predicting chronic disease susceptibility, allowing for proactive measures and improved treatment outcomes by addressing underlying genetic predispositions and risk factors. Ultimately, it enables the utilization of genetic screening and pharmacogenomics to improve patient care standards and enhance overall healthcare quality within this integrated healthcare system [

15,

16].

In our exploration of PCC and the integration of advanced conceptual frameworks like POMOCF, we introduce novel solutions to typical healthcare management challenges. With a focus on bringing a patient-centric model within EHR systems, which empowers patients to curate their health information actively, we propose a transformative approach to healthcare delivery. Exploring ontology systems and standards, we highlight the crucial significance of standardizing medical record terminologies to ensure seamless communication and data exchange among the healthcare community. Furthermore, we underscore the pivotal role of integrating chronic and genomic data in advancing patient-centered care and precision medicine initiatives, thereby significantly contributing to the continuous development of healthcare practices.

2. Materials and Methods

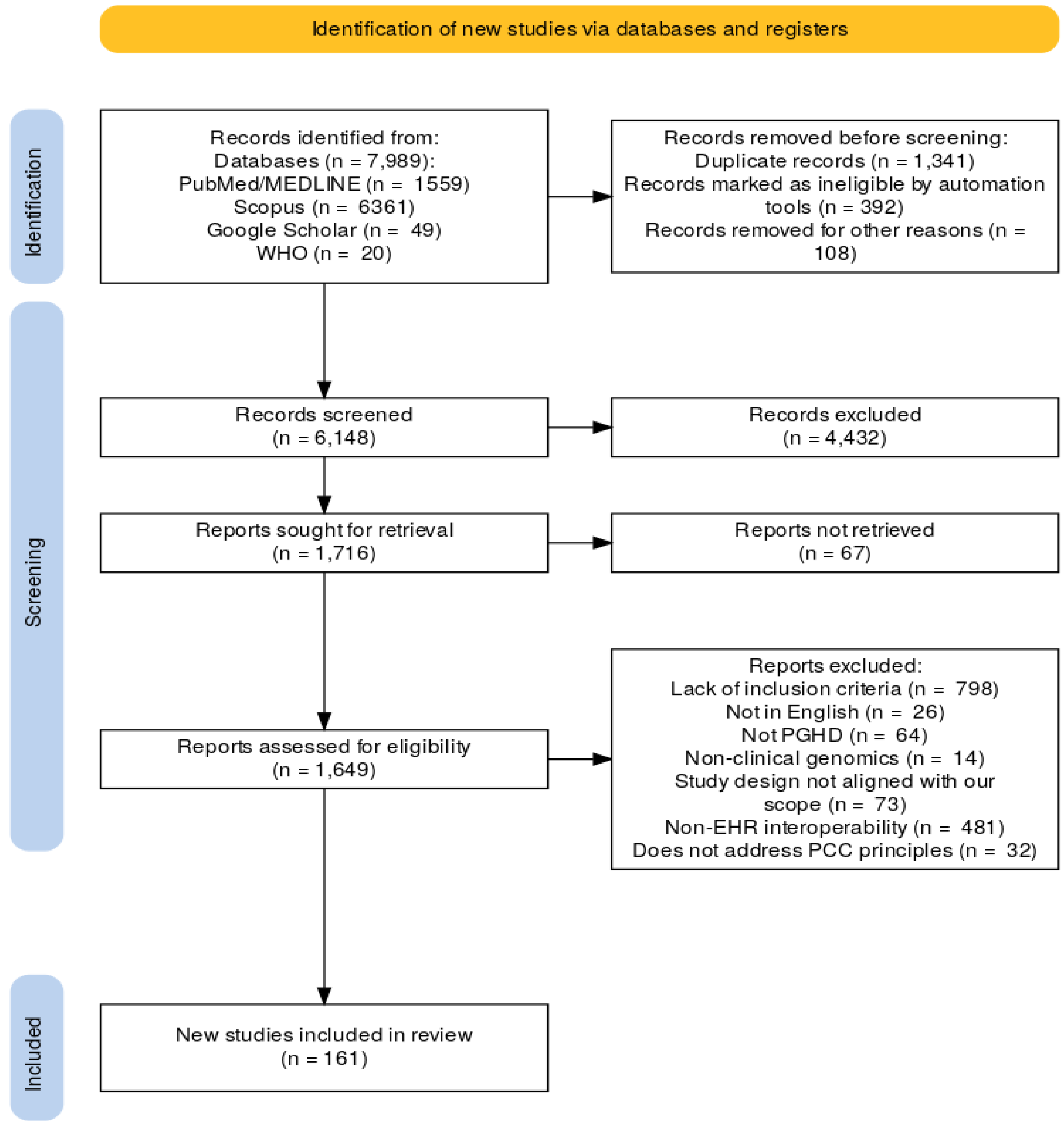

This study follows the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) general guidelines, which provide a standardized framework for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PRISMA offers an evidence-based minimum set of items to ensure comprehensive and transparent reporting in these types of studies. By adhering to PRISMA, authors aim to enhance the quality and transparency of reporting, thereby improving the reliability and reproducibility of systematic review findings. Additionally, PRISMA is a valuable resource for evaluating published systematic reviews, although it is designed for something other than quality assessment [

17].

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

Studies were identified up to March 15, 2024. The selection process involved searching various online databases. The five databases that retrieved the most unique references are PubMed, MEDLINE, Scopus, Google Scholar, and the World Health Organization (WHO). MEDLINE and PubMed were considered single databases since PubMed encompasses all the references found in MEDLINE. We initially retrieved 100 articles from Google Scholar. However, due to the abundance of relevant articles obtained from other databases, we decided to limit the number of articles from Google Scholar to 30. The search encompassed online books, published papers, conference abstracts, seminars, and reference publications to mitigate publication bias and ensure the inclusivity of relevant articles. Furthermore, reference lists of selected articles were manually searched for additional pertinent studies. Additionally, the bibliographies of articles and reviews were hand-searched for potentially relevant publications. An email alert system was set up within the electronic databases to monitor newly released publications meeting the selection criteria based on saved search histories up to 15 March 2024.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy was formulated based on the key concepts outlined in the research objectives, encompassing terms such as "Electronic Health Record," "Computerized Medical Record," "Automated Medical Record," "Clinical Information System," "Health Information System," "Hospital Information System," "Medical Record System," "Genomic data," "Ontology integration," "Chronic conditions," "Patient-centered care," "Patient-Generated Health Data," "Patient empowerment," "Interoperability," "Healthcare standards," "Semantic web technologies," "Healthcare quality," "Healthcare delivery," "Patient outcomes," "Data exchange," and "Database design." Boolean operators such as AND, OR, and NOT were used to refine the search terms. Quotation marks ensured phrases were searched as exact terms, while wildcard characters (*) and truncation covered variations in word endings. Parentheses ( ) grouped terms to control the search order. This comprehensive strategy ensured a thorough and systematic search of relevant databases.

Articles potentially relevant to the study were initially screened based on their titles and imported into Rayyan. Further selection criteria included assessing abstracts and full-text articles using Rayyan's screening tools [

18].

2.3. Article Selection

The PRISMA flow chart in

Figure 1 outlines the entire article selection process. Following the establishment of inclusion and exclusion criteria, as detailed in

Table 1, articles underwent thorough screening. Titles were first assessed for relevance, followed by abstract reviews and a comprehensive review of full-text articles. The article selection process was designed to include only relevant research that met the predefined criteria, maintaining the study findings' integrity and validity. The review protocol is registered under the “International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews” (PROSPERO) [

19] database (PROSPERO 2024 CRD42024555474)].

3. Conceptualization of Patient-Oriented Medical Ontology Conceptual Framework (POMOCF)

In accordance with our mission to develop a comprehensive healthcare information system, we present the POMOCF. This framework falls within the broader domain of healthcare ontology and informatics, aims to improve PCC and healthcare information management by integrating medical ontology principles. Medical ontology plays a crucial role in advancing healthcare systems by providing a structured framework for organizing and representing medical knowledge. Within the context of POMOCF, medical ontology facilitates the standardization of medical terminologies, definition of clinical concepts, and semantic interoperability between different healthcare systems.

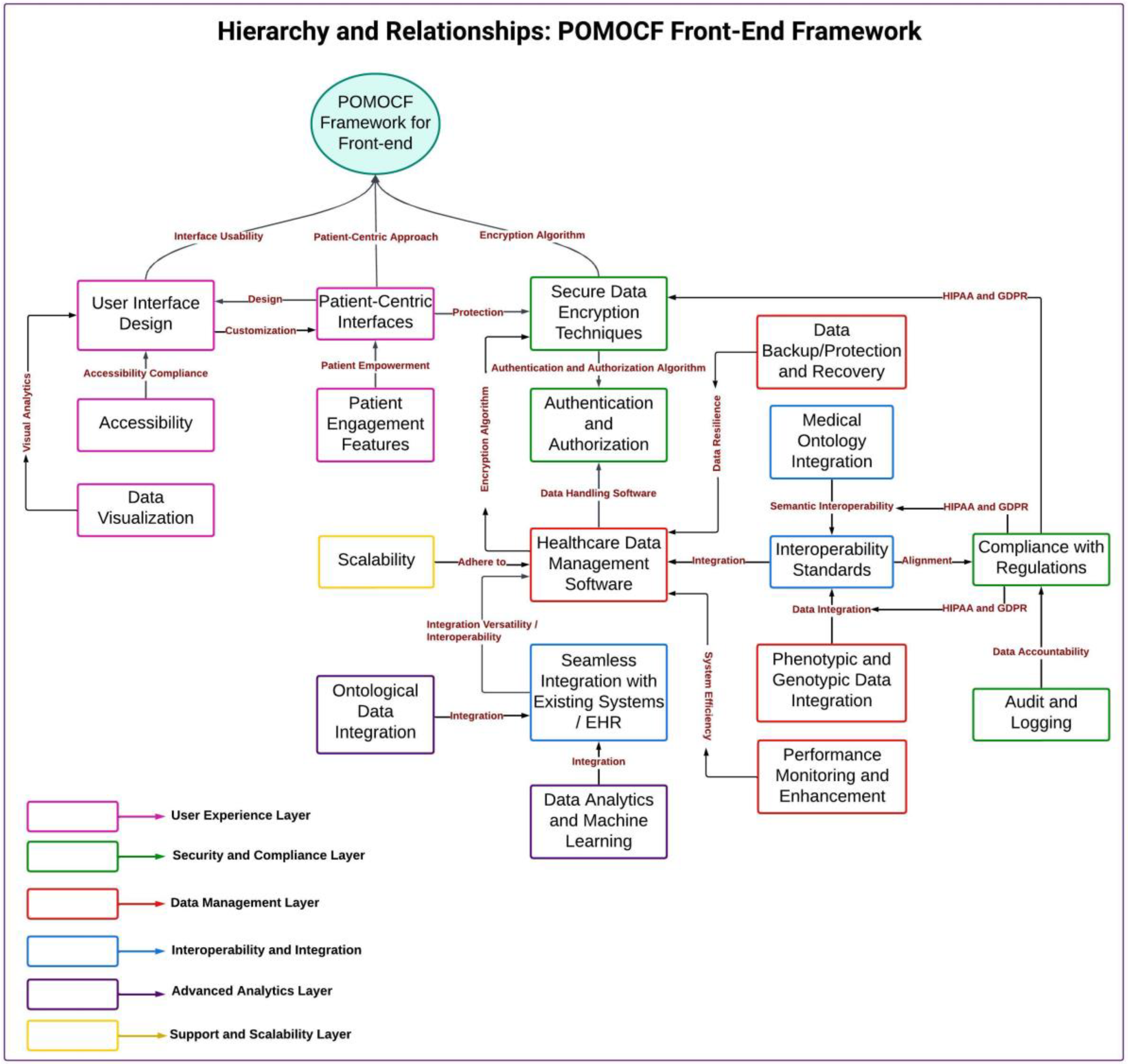

POMOCF will encompass both front-end and back-end components, creating a holistic system that addresses the needs of patients and healthcare providers. By "front-end," we refer to the user-facing aspects of the system that patients and healthcare providers interact with directly, such as interfaces and applications. "Back-end" refers to the server-side infrastructure responsible for data processing, storage, and security. Our current mission focuses on the conceptualizing and developing of the front-end framework, which prioritizes user-friendly interfaces and seamless access to healthcare data. Key components of the front-end framework include patient-centric interfaces, robust authentication and authorization mechanisms, secure data encryption techniques, seamless integration with existing healthcare systems, and dedicated healthcare data management software.

The back-end framework of POMOCF is a testament to our commitment to advanced technologies and medical ontology integration. We are currently in the process of assessing the feasibility of this integration and planning the necessary infrastructure. The back-end framework of POMOCF plans will leverage advanced technologies like Neo4j graph databases for efficient data management, including patient records, genomic data, and ontology mappings. The integration of medical ontology principles will standardize terminologies and ensure semantic interoperability across healthcare systems, supported by specialized and existing ontologies like Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) and Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC). These features enable advanced functionalities such as ontology-based reasoning and semantic querying, while API development facilitates seamless interaction between the front-end application and the data infrastructure, enabling secure data querying and real-time exchange.

We plan to integrate our front-end framework with the back-end framework, ensuring a cohesive system that supports comprehensive patient data management, semantic interoperability, and informed decision-making. By combining structured knowledge representation and semantic interoperability, POMOCF will facilitate seamless access to healthcare data, enhance the quality of patient care, and enable informed decision-making by patients and healthcare providers.

3.1. Front-End Framework Objectives and Scope

3.1.1. Objective

The primary objective of our front-end framework is to create a user-centric front-end framework that prioritizes the needs of patients and healthcare providers, making healthcare data more accessible and user-friendly. Our goal is to develop a front-end framework that is strategically designed to serve as the user-friendly interface that enables patients to take an active role in their healthcare experience and to make it easy for patients to access their medical records and effectively communicate with their healthcare providers, aiming to bridge the gap between users and complex healthcare data, thereby enhancing accessibility and usability.

3.1.2. Scope

Our front-end framework development extends beyond conventional user interface design. It takes a comprehensive approach, seamlessly integrating with the core functionalities of POMOCF. It encompasses the design and implementation of user interfaces that cater to fulfill the diverse requirements of healthcare stakeholders, including patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. This includes features such as user-friendly dashboards, interactive data visualization tools, secure messaging systems, and simple navigation pathways. Our framework focuses on accessibility, security, and ease of use, ensuring all users can effectively interact with the healthcare data presented through the front-end interface.

3.2. Front-End Framework Components

Table 2.

Components Used in POMOCF Framework.

Table 2.

Components Used in POMOCF Framework.

| Class |

Functionalities |

| User Experience |

Designs interfaces for seamless healthcare data interaction. |

| Security and Compliance |

Ensures data confidentiality, integrity, and regulatory compliance. |

| Data Management |

Organizes, stores, and retrieves healthcare data, ensuring integrity. |

| Interoperability and Integration |

Facilitates seamless data exchange across systems and platforms. |

| Advanced Analytics |

Utilizes analytics and AI to enhance clinical decision-making. |

| Scalability |

Addresses system capacity for growing data volumes and user loads. |

3.3. Front-End Framework Development Process

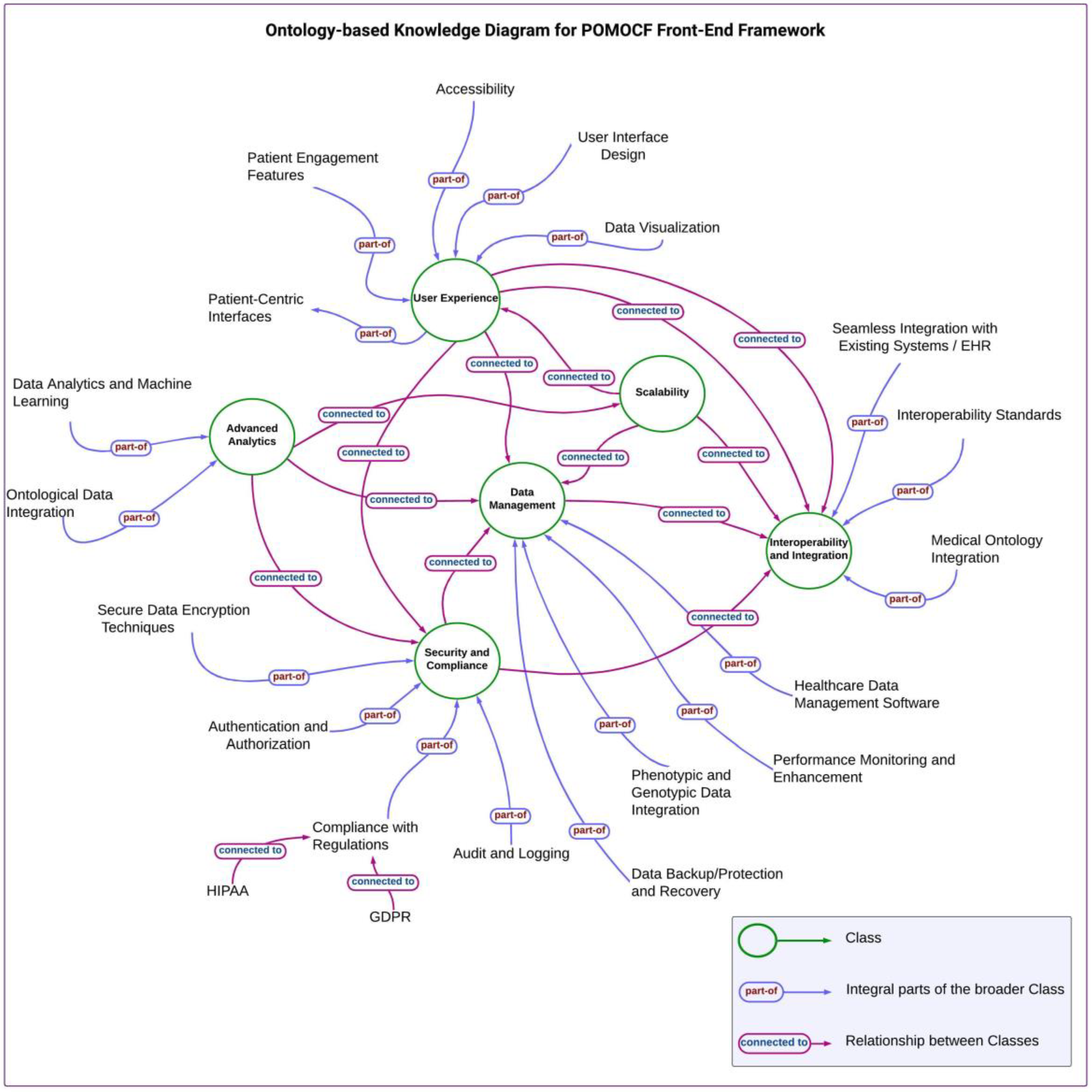

In developing our high-level medical ontology conceptual framework for front-end, we adopted a systematic approach that involved conducting a comprehensive literature review to analyze current healthcare information management frameworks, methodologies, and best practices. We identified successful strategies in user interface design, usability, and patient engagement by utilizing established methodologies like systematic literature review and qualitative analysis. Subsequently, we constructed a robust conceptual model as a visual blueprint illustrating the interconnected components and relationships within the front-end framework.

By using the identified components using a mind map, we created the ontology-based knowledge diagram (

Figure 2). This diagram visually represents the structured organization of information according to ontology principles, guiding the development of our front-end framework. We then proceeded to construct a Hierarchical Framework (

Figure 3), using the insights gathered from the ontology-based knowledge diagram to define the hierarchy and relationships among different components. Our hierarchical representation serves as a foundational structure for our front-end system, facilitating effective data organization and navigation.

During the development of our front-end system, the theoretical concepts of PCC principles were utilized as important guides. Additionally, we utilized ontology principles to structure information hierarchically within the conceptual framework, which is integral to the front-end framework. Focusing on ontology standards and best practices, we ensured that the framework facilitates semantic interoperability, standardizes terminologies, and effectively defines clinical concepts. This approach enhances data consistency and usability and supports seamless integration and communication across diverse healthcare systems.

3.3. Challenges in Developing a POMOCF Front-End Framework

3.3.1. Theoretical Framework Integration and Consistency

Developing the PCC-based framework involves ensuring theoretical coherence and consistency across diverse literature sources. Synthesizing findings from a systematic review involves navigating a multitude of theoretical perspectives and conceptual frameworks. Harmonizing these disparate viewpoints while maintaining a coherent and consistent theoretical foundation poses a significant challenge. It requires careful consideration of theoretical paradigms, methodological approaches, and underlying assumptions to ensure our conceptual framework remains conceptually robust and logically coherent.

3.3.2. Theoretical Concept Applicability and Potential Limitations

The creation of the POMOCF-based framework is not complete without ensuring its conceptual generalizability across diverse healthcare settings and user demographics. While our systematic review provides theoretical insights into the framework's conceptual foundation, it is crucial to emphasize that empirical validation is necessary to assess its applicability, usability, and effectiveness in clinical practice. The variations in clinical practices, patient demographics, and healthcare infrastructure may impact the framework's applicability. Although empirical validation studies have not yet been conducted, this theoretical foundation highlights potential limitations in applying our framework across diverse clinical environments. Overcoming methodological challenges and defining appropriate outcome measures are essential steps in conducting empirical validation studies. Continual refinement based on real-world feedback is required for enhancing the practical utility of our conceptual framework and addressing potential limitations identified through empirical validation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Significance of Front-End Frameworks

The development of the front-end framework in POMOCF is a significant advancement in PCC principles. By prioritizing user-centric design and accessibility, it empowers patients to actively engage in their healthcare. The inclusion of user-friendly interfaces and seamless data access fosters patient involvement and enhances communication with healthcare providers. This framework facilitates the integration of users with complex healthcare data, thereby facilitating informed decision-making and improving healthcare outcomes. In this way, it establishes a foundation for a patient-centric approach to healthcare delivery.

4.2. Next Steps and Case Studies in Using a High-Level Medical Ontology Conceptual Framework for Front-End

From here onward, our focus lies on advancing and expanding the high-level medical ontology conceptual framework for the front-end. We aim to enhance semantic interoperability, standardize terminologies, and effectively define clinical concepts within the framework. Incorporating feedback from stakeholders and utilizing emerging technologies, we will persistently develop the framework to address evolving healthcare demands while adhering to user-centric design principles.

The front-end framework within POMOCF serves as a versatile tool with diverse applications in healthcare delivery and patient engagement. Its user-centric design and seamless integration with existing healthcare systems make it adaptable for various use cases. For instance, Alpert et al. (2017) [

20] demonstrated a case study where user-centric patient portals were utilized to enable secure access to health records, facilitate telemedicine consultations, support remote monitoring of patient's health metrics, assist clinicians with decision-support functionalities, and serve as a foundational infrastructure for clinical research platforms.

Integrating genotypic data into healthcare systems' front-ends marks a significant advancement toward personalized medicine, aligning with our aim to enhance PCC. Our plan to incorporate genotypic information into the front-end interface holds promise for revolutionizing treatment decision-making processes. By providing clinicians with readily accessible genetic insights, we expect to observe improved accuracy in care planning and a reduction in adverse reactions. This strategic integration underscores our commitment to accuracy and PCC. In line with our scope, Williams et al. (2019) [

21] examined the challenges faced by EHR working groups, including the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) project, in integrating genotypic data. These programs aim to develop efficient and economically sustainable practical solutions supporting the realization of genomic medicine. They also provide significant ideas and knowledge that might help define future activities in this field.

Key features of the framework include its ability to provide a standardized and interoperable environment for healthcare data, ensuring secure communication between patients and providers, and its scalability to accommodate varying needs and technological advancements in healthcare delivery. By providing a robust platform for accessing and managing healthcare information, the front-end framework contributes to patient empowerment, care coordination, and improved healthcare outcomes. Hägglund et al. (2022) [

22] also underscores the importance of such features in their research, emphasizing the pivotal role of standardized environments and secure communication channels in ensuring the effectiveness and scalability of healthcare frameworks.

4.3. Future Development Strategies for POMOCF Back-End Framework: Bridging Front-End and Back-End Frameworks

As we consider the future of our healthcare information management system, the integration of our front-end framework with a robust back-end infrastructure is an essential phase. While we are currently focused on establishing the front-end framework that will empower patients and improve access to healthcare data, we recognize the importance of developing the groundwork for a comprehensive back-end solution to serve as the foundation of our healthcare information ecosystem.

The back-end framework serves as the backbone for various use cases aimed at improving healthcare delivery and patient outcomes. One key use case is the seamless management of patient data, ensuring its secure storage, efficient retrieval, and accurate representation [

23]. Another use case involves integrating genomic information into healthcare systems, enabling personalized medicine initiatives and precision healthcare interventions [

24]. Additionally, the back-end framework supports the implementation of PCC principles, facilitating active patient involvement in treatment decisions and health management. Moreover, it enables the monitoring and analysis of healthcare quality and outcomes, providing insights to optimize care delivery processes and enhance patient satisfaction [

25]. In our future back-end framework, we plan to integrate key components such as healthcare data storage database, ontology integration, API development, healthcare standards, genomic data integration, conceptual framework construction, PCC principles, data security and privacy, healthcare quality and outcomes, and analytical tools. Together, these components will form the backbone of our comprehensive healthcare information management system, enabling effective patient data management, seamless integration of genomic information, utilizing ontology-based knowledge representation, and facilitating API development for enhanced interoperability. In the POMOCF framework, front-end tools primarily focus on user interfaces and interaction design, presenting data to users and facilitating their engagement with the system. Conversely, back-end tools manage data storage, processing, and analytical tasks, ensuring data integrity and supporting decision-making processes.

4.3.1. Proposed Integration of Medical Ontology across Front-End and Back-End Framework

Our study underscores the pivotal role of integrating medical ontology into front-end interfaces within healthcare systems. By focusing on phenotypic and genotypic data integration, we have demonstrated how this approach advances PCC principles by enhancing data accessibility and interoperability. However, our study also identifies several research gaps which require further exploration. Real-world validation of our framework's effectiveness, rigorous adherence to interoperability standards such as HL7 FHIR and SNOMED CT, and integration of emerging technologies like semantic web technologies are essential for advancing the reliability and compatibility of our proposed framework.

In the domain of healthcare, efficient management of patient data and seamless integration of various healthcare processes are essential for enhancing patient care and outcomes. To achieve this, POMOCF will be instrumental and can contribute to the design of a comprehensive healthcare information management system by structuring and standardizing healthcare data, ensuring holistic and efficient management of healthcare information through its front-end and back-end components.

We explore the technological aspects that facilitate the seamless integration of EHR systems. Every healthcare provider today utilizes some type of EHR technology. However, achieving seamless integration across different healthcare providers requires a unified healthcare platform incorporating ontology and common standardization systems [

26]. Because different healthcare organizations utilize different terminologies, ontology is essential to facilitating the seamless sharing of health information. Standardizing medical record terminologies is essential for effective communication among healthcare professionals and organizations [

27]. Interoperability and adherence to standards are fundamental aspects within EHR systems are pivotal for ensuring the safety and efficacy of patient care. Since 2003, there has been a growing focus on achieving interoperability in health information systems, capturing the attention of academics and becoming a top priority. Interoperability enables seamless communication among diverse hardware and software platforms, ensuring the uninterrupted transfer of patient data across varied settings [

28,

29]. Various technologies and architectures, including Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), use these standardized systems and ontologies to facilitate the integration of different EHR systems [

30]. Additionally, semantic web technologies like SPARQL, OWL (Web Ontology Language), RDF Schema (RDFS), RDFa (Resource Description Framework in Attributes), GRDDL (Gleaning Resource Descriptions from Dialects of Languages), and OWL-S (OWL for Services) facilitate the querying and retrieving of data based on semantic relationships encoded in ontologies.

These technologies are foundational to the Semantic Web infrastructure, enabling advanced functionalities such as data querying through SPARQL (which is constructed upon RDF), ontology-based reasoning utilizing RDFS and OWL (both built atop RDF), semantic annotation facilitated by RDFa and GRDDL (both reliant on the RDF model), and service description facilitated by OWL-S [

31,

32]. However, the integration of various systems presents considerable challenges, such as ensuring adherence to established standards such as Health Level Seven Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (HL7 FHIR), Clinical Document Architecture (CDA), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and SNOMED-CT, as well as overcoming interoperability challenges arising from disparities in data formats and structures, continues to be a significant concern. Data standards like HL7 and FHIR are instrumental in ensuring seamless data exchange across healthcare organizations. HL7 FHIR defines data format, elements, and structure, facilitating interoperability. Additionally, terminology standards such as SNOMED CT standardize clinical codes, resolving discrepancies in textual descriptions when data is being transcribed. Adherence to regulations like CDA, HIPAA, and SNOMED CT is crucial for maintaining data security and integrity. CDA sets standards for clinical document exchange, HIPAA safeguards patient information, and SNOMED CT standardizes clinical coding, which improves interoperability [

28,

33]. Additionally, deploying key technologies, including API, Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA), Reference Information Model (RIM), Extensible Markup Language (XML), Java (a programming language), and Structured Query Language (SQL), requires careful consideration of compatibility and scalability to ensure seamless integration across diverse healthcare environments [

29,

34].

Our paper introduces innovative solutions to address the existing challenges in healthcare information management. In line with our objective of allowing patients to manage their health information within EHRs, we will suggest the integration of HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) with Ontobee and Common Core Ontologies. This integrated solution addresses the need for a front-end application to access patient data, genomic data, and ontology mappings, particularly for chronic disease management. By harnessing the semantic richness and broad coverage of Ontobee and Common Core Ontologies, along with the specialized gene nomenclature and detailed genetic disorder information provided by HGNC and OMIM, our approach significantly enhances the application's ability to provide comprehensive genomic details to patients. Integrating these distinct data sources facilitates a more holistic understanding of patients' health profiles, enabling personalized and effective interventions that ultimately improve patient outcomes. This integration also ensures interoperability between EHR systems, thereby enhancing data exchange and accessibility.

We further elaborate on the ontology systems and standards that enable this integration, providing insights into the structural conceptual frameworks supporting our patient-centric approach to healthcare management. The incorporation of ontologies into EHR systems enhances data interoperability by establishing standardized data exchange protocols and terminologies. This aims to facilitate seamless data sharing among all sectors within the organization, including clinicians, nurses, laboratory staff, and across the entire hospital infrastructure. By standardizing the data, healthcare professionals, researchers, and institutions can share and communicate medical information, even if there are differences in terminology and data in different formats. Ultimately, ontologies facilitate healthcare organizations to fully utilize chronic and genomic data within EHRs, leading to progress in personalized medicine, clinical decision support, and healthcare delivery.

Our study addresses an essential healthcare information management gap by proposing a comprehensive system for managing patient data, genomic information, and ontology mappings within a patient-centered front-end application. We will outline recommendations encompassing database design, ontology integration, and API development to achieve this. Firstly, we will highlight the significance of designing a database schema that can efficiently store and manage diverse datasets, including patient records, genomic data, and ontology mappings. Graph databases like Neo4j are suggested for their ability to handle complex relationships identified by healthcare data. Subsequently, our approach involves integrating a custom ontology with existing medical ontologies to establish semantic relationships and facilitate data retrieval. This integration allows for the querying and accessing of data through established semantic relationships, typically achieved through the use of SPARQL queries over RDF data. Finally, we strongly support the development of APIs that facilitate seamless interaction between the front-end application and the back-end database and ontology system. These APIs serve as the bridge for securely querying patient data, accessing genomic information, and retrieving ontology-based insights. By implementing these recommendations, our study aims to establish a robust back-end infrastructure supporting personalized healthcare delivery and improved decision-making. Furthermore, by outlining the framework's conceptualization, component identification, construction, ontology integration, and continuous enhancement, we provide the foundation for future evaluation and validation efforts. We aim to establish a robust conceptual framework that supports personalized healthcare delivery and improved decision-making.

5. Conclusions

Our study underscores the pivotal role of integrating medical ontology into front-end interfaces within healthcare systems. By focusing on phenotypic and genotypic data integration, we have demonstrated how this approach advances PCC principles by enhancing data accessibility and interoperability. The incorporation of medical ontology into front-end interfaces within healthcare systems, especially in the integration of phenotypic and genotypic data, signifies a significant advancement towards PCC. Our comprehensive review highlights critical research gaps and outlines future directions, with a strong emphasis on the necessity for empirical validation, strict adherence to interoperability standards, and integration of emerging technologies. These measures are crucial to ensuring the reliability and compatibility of the proposed framework. Through the strategic integration of the most effective ontological principles with advanced technological solutions, we expect an important advancement toward improved accessibility, personalized care, and improved patient outcomes. This approach, characterized by features like user-friendly dashboards, secure messaging systems, and simple navigation pathways, ensures effective interaction with healthcare data for all stakeholders. It offers a comprehensive solution for researchers, developers, healthcare providers, policymakers, and technology experts in designing and implementing healthcare information systems, seamlessly integrating both front-end and back-end components for unified healthcare management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.S.S., J.M., and R.A.; Theoretical framework: R.S.S., J.M., R.A., R.P., and K.K.; Investigation: R.S.S. and J.M.; Resources: R.S.S.; Literature review: R.A., J.M., and R.S.S.; Conceptual analysis: R.S.S., J.M., R.A., I.P.N., R.P., and S.P.; Writing—original draft preparation: R.S.S., R.A., and J.M.; Writing—review and editing: R.S.S., J.M., R.A., A.M., G.T., and M.M.K.; Visualization: R.A., R.P., K.K and R.S.S.; Supervision: R.S.S., I.P.N., R.P., and S.P.; Revision of the manuscript: I.P.N., R.P., S.P., A.M., G.T., and M.M.K.; Project administration: J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As this study is a systematic review, it did not involve direct interaction with human participants or the use of identifiable data. Therefore, ethical approval was not required for this review.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this study primarily consists of qualitative information extracted from published literature and other relevant sources to develop a conceptual framework. The conceptual framework is available upon request from the corresponding authors from The Self Research Institute for scholarly and non-commercial purposes, including detailed descriptions of study methodologies, findings, and other relevant qualitative information utilized in the synthesis process. The protocol detailing the systematic review process is publicly available in PROSPERO [CRD42024555474], ensuring transparency in the methodology used to develop the framework.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Megari, K. Quality of Life in Chronic Disease Patients. Health Psychol. Res. 2013, 1, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrow, M. Caring for People with Chronic Conditions: A Health System Perspective. Int. J. Integr. Care 2009, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, V. The next Generation of Evidence-Based Medicine. Nat. Med. 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving Chronic Illness Care: Translating Evidence into Action. Health Aff. Proj. Hope 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Care Coordination. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/care/coordination.html (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Vahdat, S.; Hamzehgardeshi, L.; Hessam, S.; Hamzehgardeshi, Z. Patient Involvement in Health Care Decision Making: A Review. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2014, 16, e12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Improving the Patient Record The Computer-Based Patient Record: Revised Edition: An Essential Technology for Health Care; Dick, R. S., Steen, E.B., Detmer, D.E., Eds.; National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 1997; ISBN 978-0-309-05532-1. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R.S. Electronic Health Records: Then, Now, and in the Future. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2016, Suppl 1, S48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Medical Association. Meaningful Use: Electronic Health Record (EHR) Incentive Programs. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/meaningful-use-electronic-health-record-ehr-incentive (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Office-Based Physician Electronic Health Record Adoption | HealthIT.Gov. Available online: https://www.healthit.gov/data/quickstats/office-based-physician-electronic-health-record-adoption (accessed on 3 April 2024).

-

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 2001; ISBN 978-0-309-07280-9.

- Ambalavanan, R.; Snead, R.S.; Marczika, J.; Kozinsky, K.; Aman, E. Advancing the Management of Long COVID by Integrating into Health Informatics Domain: Current and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blobel, B. Authorisation and Access Control for Electronic Health Record Systems. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2004, 73, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelek, J.; Baca-Motes, K.; Pandit, J.A.; Berk, B.B.; Ramos, E. The Power of Patient Engagement With Electronic Health Records as Research Participants. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e39145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abul-Husn, N.S.; Kenny, E.E. Personalized Medicine and the Power of Electronic Health Records. Cell 2019, 177, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayatollahi, H.; Hosseini, S.F.; Hemmat, M. Integrating Genetic Data into Electronic Health Records: Medical Geneticists’ Perspectives. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2019, 25, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating Guidance for Reporting Systematic Reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, A.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Moher, D.; Petticrew, M.; Stewart, L. An International Registry of Systematic-Review Protocols. The Lancet 2011, 377, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpert, J.M.; Krist, A.H.; Aycock, R.A.; Kreps, G.L. Designing User-Centric Patient Portals: Clinician and Patients’ Uses and Gratifications. Telemed. J. E-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2017, 23, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.S.; Taylor, C.O.; Walton, N.A.; Goehringer, S.R.; Aronson, S.; Freimuth, R.R.; Rasmussen, L.V.; Hall, E.S.; Prows, C.A.; Chung, W.K.; et al. Genomic Information for Clinicians in the Electronic Health Record: Lessons Learned From the Clinical Genome Resource Project and the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics Network. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hägglund, M.; McMillan, B.; Whittaker, R.; Blease, C. Patient Empowerment through Online Access to Health Records. BMJ 2022, 378, e071531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenstein, V.; Kharrazi, H.; Lehmann, H.; Taylor, C.O. Obtaining Data From Electronic Health Records. Tools and Technologies for Registry Interoperability, Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide, 3rd Edition, Addendum 2 [Internet], /: for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2019. Available online: https, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, D.E.; Moeckel, F.; Villa, M.S.; Housman, L.T.; McCarty, C.A.; McLeod, H.L. Strategies for Integrating Personalized Medicine into Healthcare Practice. Pers. Med. 2017, 14, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, D.C.; Vieira, I.; Pedro, M.I.; Caldas, P.; Varela, M. Patient Satisfaction with Healthcare Services and the Techniques Used for Its Assessment: A Systematic Literature Review and a Bibliometric Analysis. Healthc. Basel Switz. 2023, 11, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; DesRoches, C.M.; Campbell, E.G.; Donelan, K.; Rao, S.R.; Ferris, T.G.; Shields, A.; Rosenbaum, S.; Blumenthal, D. Use of Electronic Health Records in U.S. Hospitals. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1628–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.Y.; Arabandi, S.; Beale, T.; Duncan, W.D.; Hicks, A.; Hogan, W.R.; Jensen, M.; Koppel, R.; Martínez-Costa, C.; Nytrø, Ø.; et al. Improving the Quality and Utility of Electronic Health Record Data through Ontologies. Stand. Basel Switz. 2023, 3, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiase, V.L.; Hull, W.; McFarland, M.M.; Sward, K.A.; Del Fiol, G.; Staes, C.; Weir, C.; Cummins, M.R. Patient-Generated Health Data and Electronic Health Record Integration: A Scoping Review. JAMIA Open 2020, 3, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torab-Miandoab, A.; Samad-Soltani, T.; Jodati, A.; Rezaei-Hachesu, P. Interoperability of Heterogeneous Health Information Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2023, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dullabh, P.; Hovey, L.; Heaney-Huls, K.; Rajendran, N.; Wright, A.; Sittig, D.F. Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) in Health Care: Findings from a Current-State Assessment. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 265, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houssein, E.H.; Ibrahem, N.; Zaki, A.M.; Sayed, A. Semantic Protocol and Resource Description Framework Query Language: A Comprehensive Review. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandon, F.; Krummenacher, R.; Han, S.-K.; Toma, I. The Resource Description Framework and Its Schema; Handbook of Semantic Web Technologies, 2011; ISBN 978-3-540-92912-3.

- Zheng, F.; Shi, J.; Cui, L. A Lexical-Based Approach for Exhaustive Detection of Missing Hierarchical IS-A Relations in SNOMED CT. AMIA. Annu. Symp. Proc. 2021, 2020, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, N.R. de; Santos, Y. de R. dos; Mendes, A.C.R.; Barbosa, G.N.N.; Oliveira, M.T. de; Valle, R.; Medeiros, D.S.V.; Mattos, D.M.F. Storage Standards and Solutions, Data Storage, Sharing, and Structuring in Digital Health: A Brazilian Case Study. Information 2024, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).