Submitted:

01 July 2024

Posted:

02 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

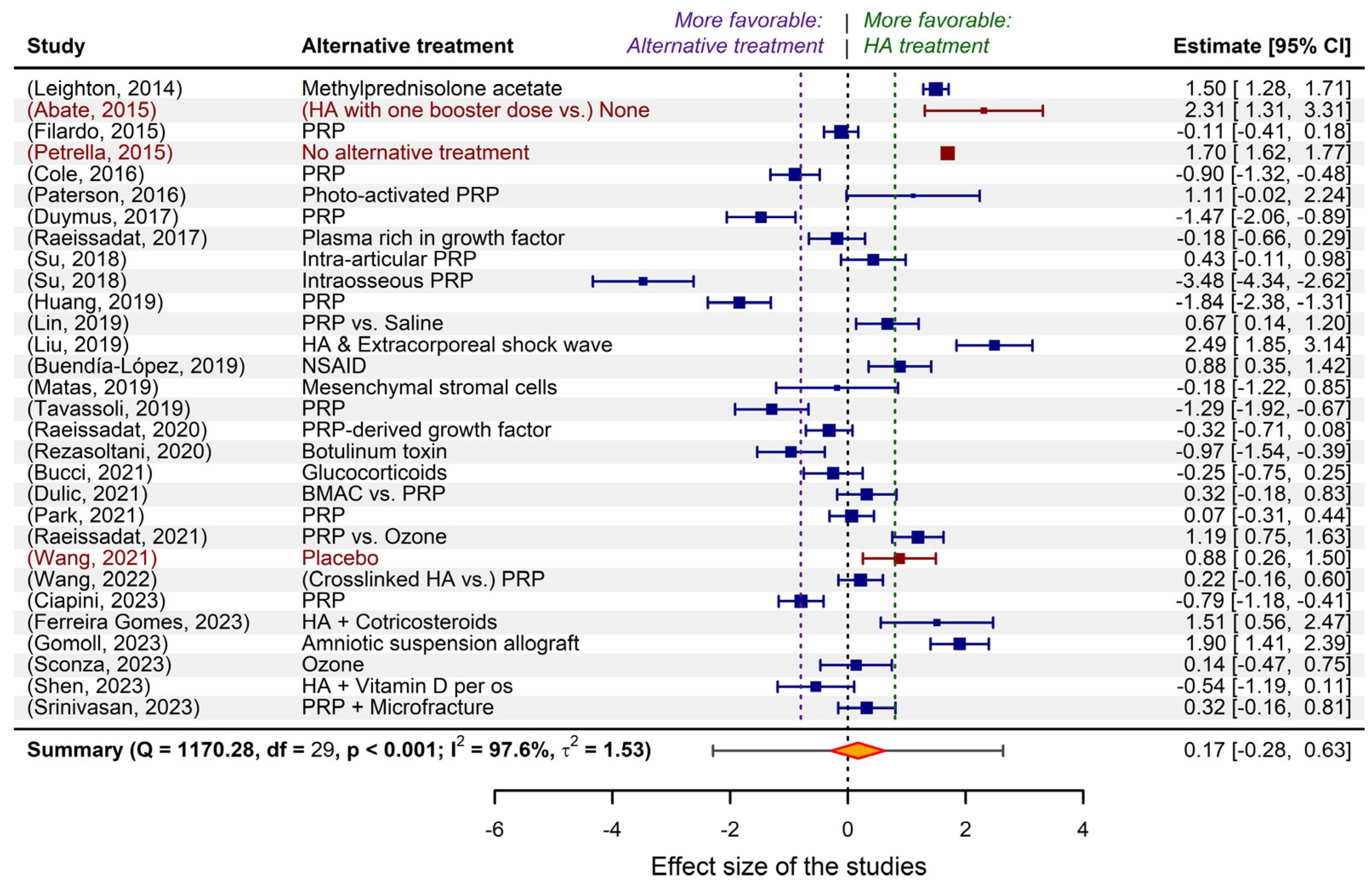

2.1. The “wide landscape” of non-surgical osteoarthritis treatments, in meta-analytical terms

2.2. Criteria derived from a clinical perspective for limiting the selected studies

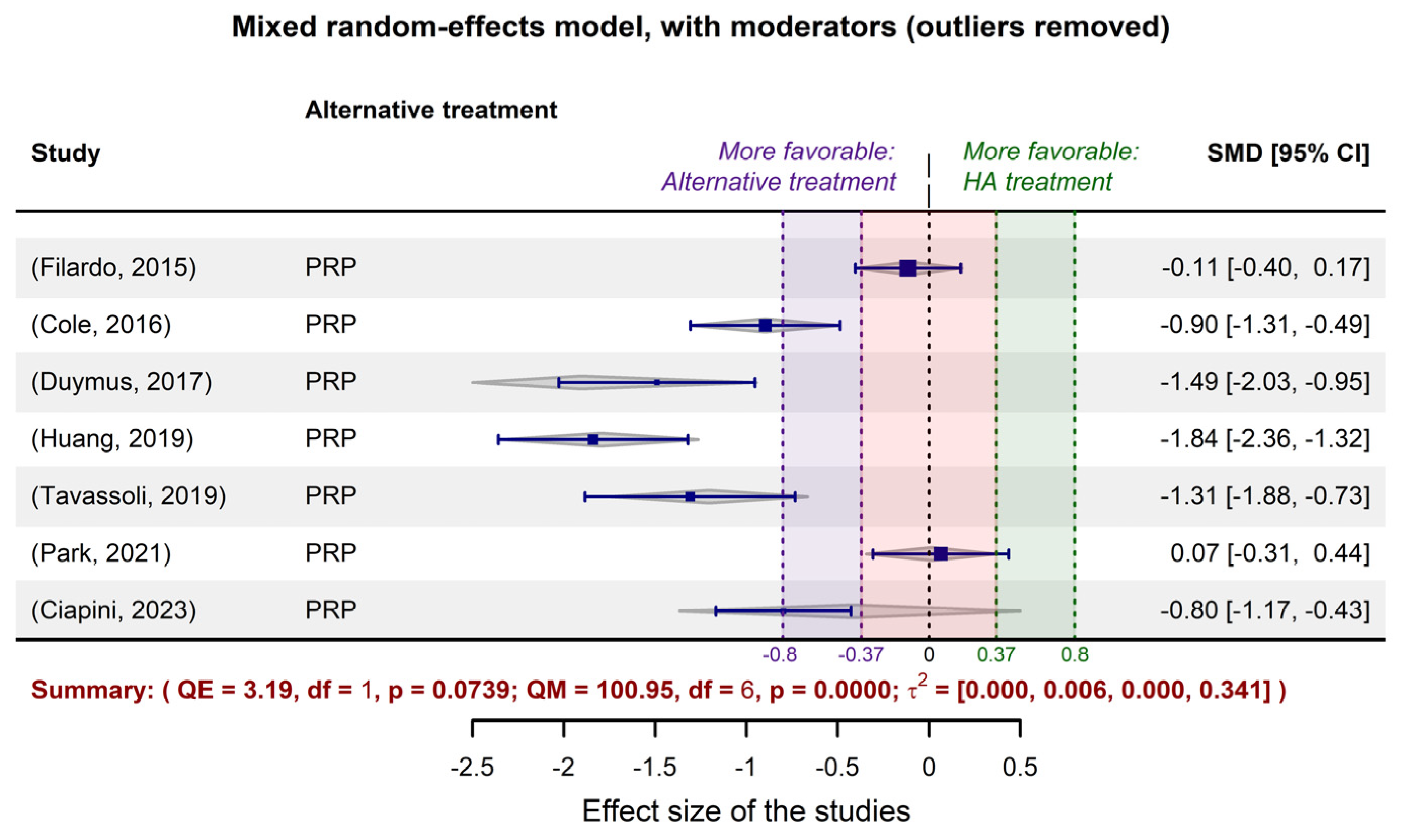

2.3. Fitting meta-analytic models to the data extracted from the limited selection of studies

- -

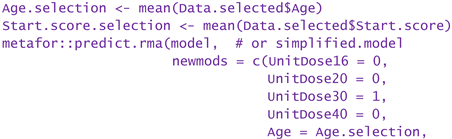

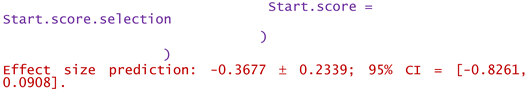

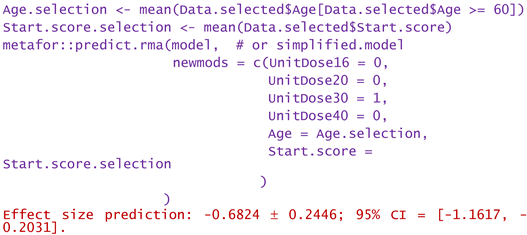

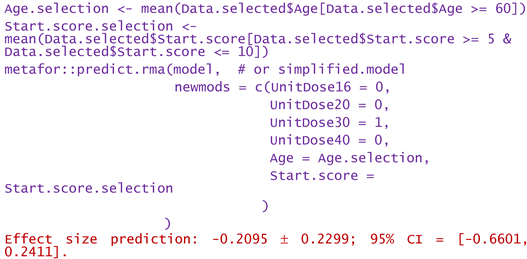

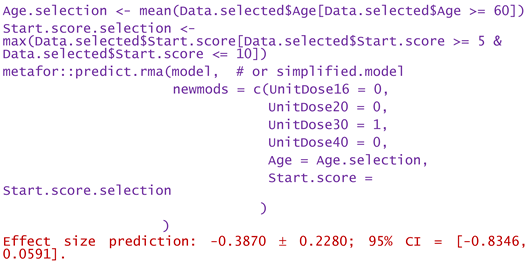

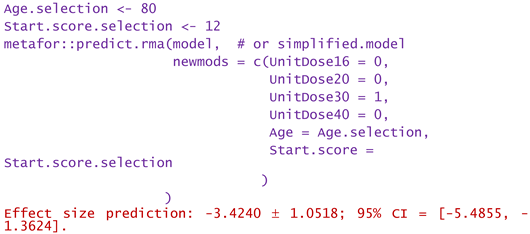

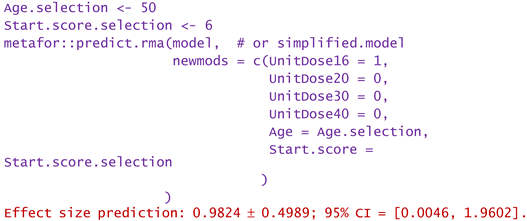

- For a patient of aged 80 and reported WOMAC pain score of 12:

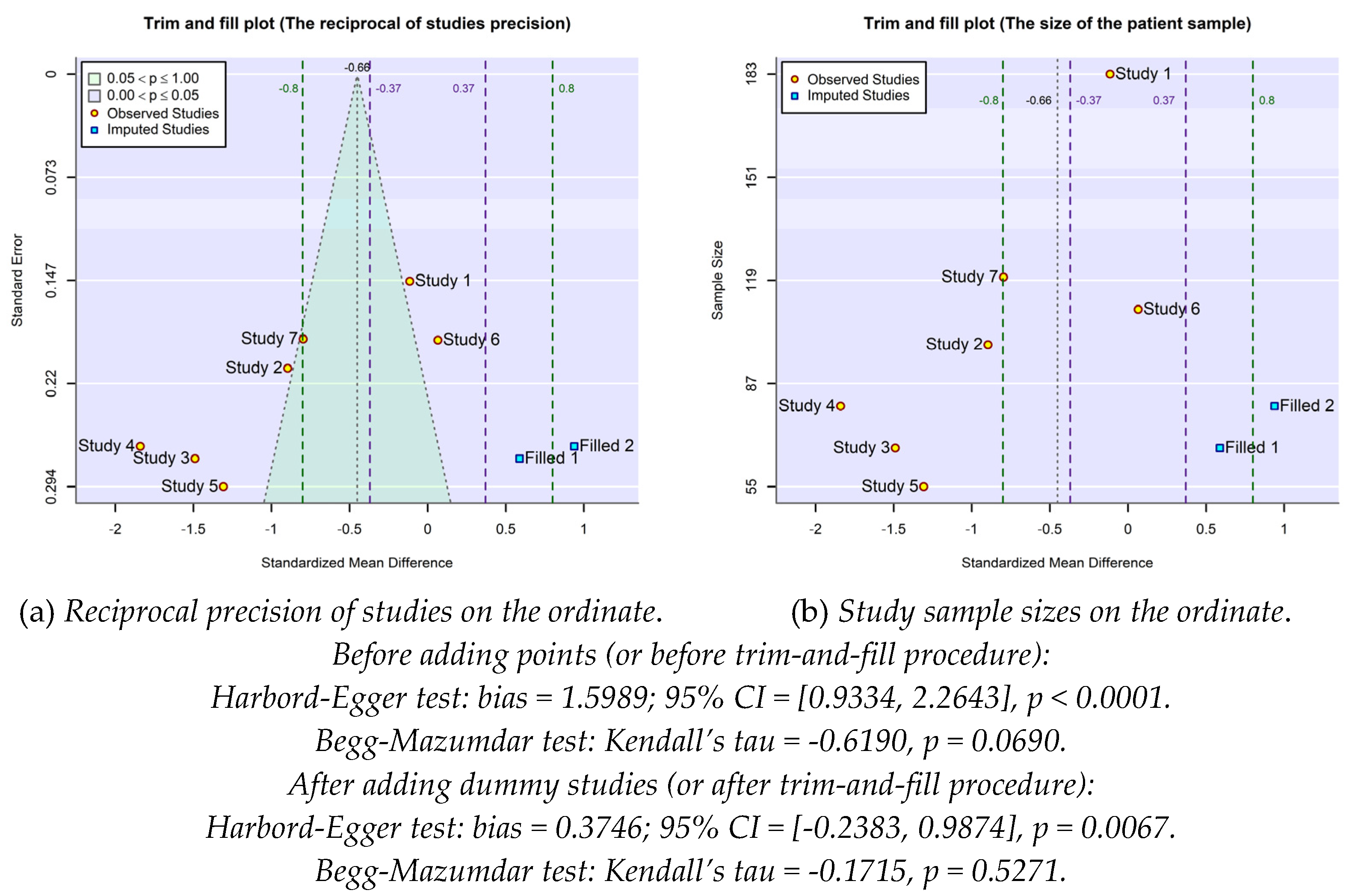

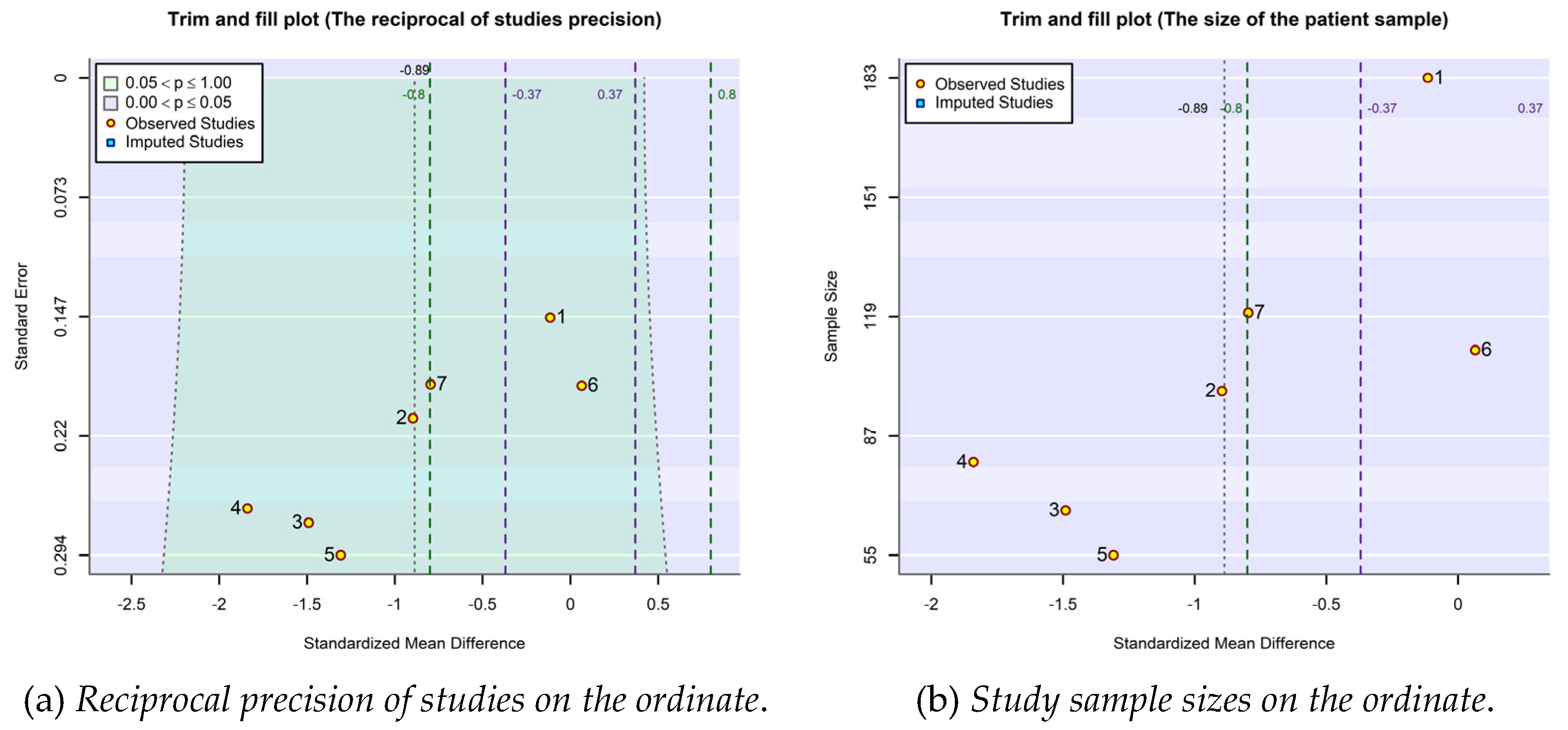

2.4. Publication bias

3. Conclusions

4. Methods of statistical investigation

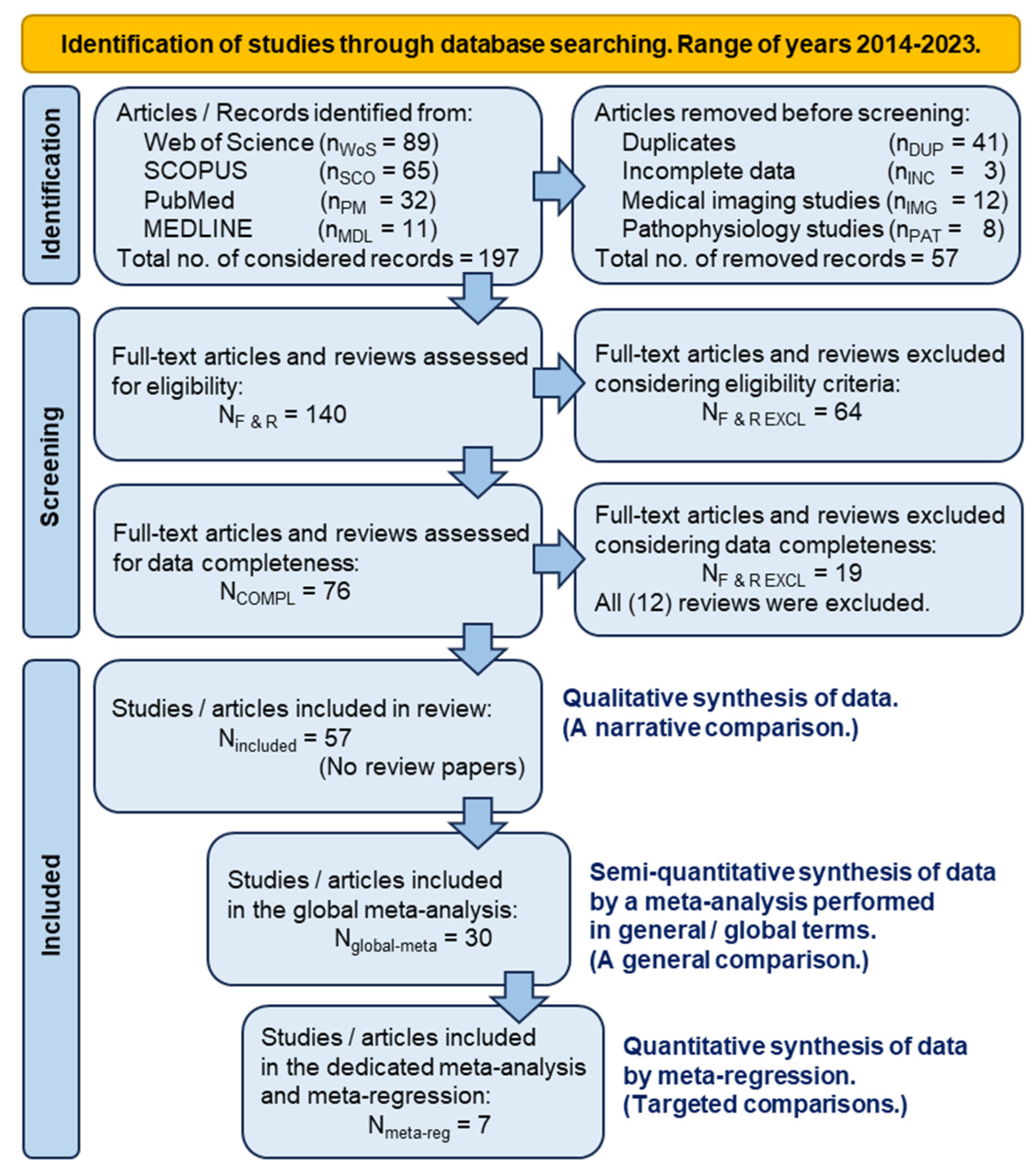

4.1. The retrospective study in PRISMA terms

4.2. The process of selecting articles of interest

4.3. The semi-quantitative synthesis of comparison data by meta-analysis

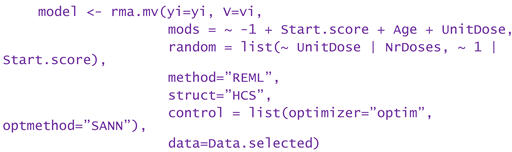

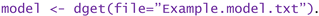

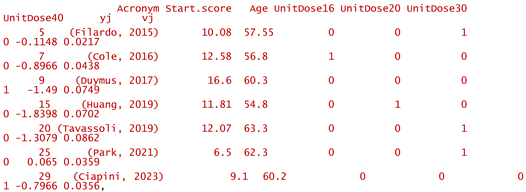

4.4. The quantitative synthesis of comparison data by dedicated meta-analysis and meta-regression

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prevalence of osteoarthritis, its causes, and prevention. Available online: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/prevalence-of-osteoarthritis (accessed on June 5, 2024).

- Gezer, H.H.; Ostor, A. What Is New in Pharmacological Treatment for Osteoarthritis? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 37(2), 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.-D.; Chen, H.-C.; Huang, M.-H.; Liou, T.-H.; Lin, C.-L.; Huang, S.-W. Comparative Efficacy of Intra-Articular Injection, Physical Therapy, and Combined Treatments on Pain, Function, and Sarcopenia Indices in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(7), 6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Householder, N.A.; Raghuram, A.; Agyare, K.; Thipaphay, S.; Zumwalt, M. A Review of Recent Innovations in Cartilage Regeneration Strategies for the Treatment of Primary Osteoarthritis of the Knee: Intra-Articular Injections. Orthop J Sports Med 2023, 11(4), 23259671231155950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaquero-Picado, A.; Rodríguez-Merchán, E.C. Intra-articular Injections of Corticosteroids and Hyaluronic Acid in Knee Osteoarthritis. In Comprehensive Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. Recent Advances; Rodríguez-Merchán, E.C., Gómez-Cardero, P., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2020, pp. 25–29.

- Sconza, C.; Di Matteo, B.; Queirazza, P.; Dina. A.; Amenta, R.; Respizzi, S.; Massazza, G.; Ammendolia, a.; Kon, E.; de Sire, A. Ozone Therapy versus Hyaluronic Acid Injections for Pain Relief in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: Preliminary Findings on Molecular and Clinical Outcomes from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(10), 8788. [CrossRef]

- Testa, G.; Giardina, S.M.C.; Culmone, A.; Vescio, A.; Turchetta, M.; Cannavò, S.; Pavone, V. Intra-Articular Injections in Knee Osteoarthritis: A Review of Literature. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021, 6(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Patent 7060466 / 2006, Methods of producing hyaluronic acid using a recombinant hyaluronan synthase gene.

- Serra, M.; Casas, A.; Toubarro, D.; Novo Barros, A.; Teixeira, J.A. Microbial Hyaluronic Acid Production: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28(5), 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Patent EP3498262B1 / 2021, Hyaluronic acid injectable gel.

- United States Patent 11191776B1 / 2021, Hyaluronic acid formulation.

- United States Patent 10821131B2 / 2020, Pharmaceutical formulations comprising chondroitin sulfate and hyaluronic acid derivatives.

- United States Patent 11013813B2 / 2021, Conjugates of stanozolol and hyaluronic acid.

- Sturabotti, E.; Consalvi, S.; Tucciarone, L.; Macrì, E.; Di Lisio, V.; Francolini, I.; Minichiello, C.; Piozzi, A.; Vuotto, C.; Martinelli, A. Synthesis of Novel Hyaluronic Acid Sulfonated Hydrogels Using Safe Reactants: A Chemical and Biological Characterization. Gels 2022, 8, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Patent 8846640B2 / 2014, Viscoelastic gels as novel fillers.

- United States Patent 10058499B2 / 2018, Sterilized composition comprising at least one hyaluronic acid and magnesium ascorbyl phosphate.

- Nichols, M.; Manjoo, A; Shaw, P.; Rosen, J. Rheological Properties of Commercially Available Hyaluronic Acid Products in the United States for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis Knee Pain. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2018, 11, 1179544117751622. [CrossRef]

- Murali, A.; Khan, I; Tiwari, S. Navigating the treatment landscape: Choosing between platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and hyaluronic acid (HA) for knee osteoarthritis management – A narrative review. JOREP 2024, 3, 100248. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, H.; Jayaram, P.; Bratsman, A.; Gabel, T.; Alba, K. Characterization and rheology of platelet-rich plasma. J. Rheol. 2020, 64(5), 1017–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoi, T.T.F.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Huber, S.C.; Santana, M.H.A.; da Fonseca, L.F.; Santos, G.S.; Azzini, G.O.M.; Mosaner, T.; Paulus-Romero, C.; Lana, J.F.S.D. Platelet-Rich Plasma Gel Matrix (PRP-GM): Description of a New Technique. Bioengineering (Basel) 2022, 9(12), 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, H.; Liang, G.; Zeng, L.; Yang. W.; Liu, J. Effects and safety of the combination of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and hyaluronic acid (HA) in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2020, 21, 224. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Sharma, S.P.; Potty, A.G. Combination of Platelet-Rich Plasma and Hyaluronic Acid vs. Platelet-Rich Plasma Alone for Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciapini, G.; Simonetti, M.; Giuntoli, M.; Varchetta, G.; De Franco, S.; Ipponi, E.; Scaglione, M.; Parchi, P.D. Is the Combination of Platelet-Rich Plasma and Hyaluronic Acid the Best Injective Treatment for Grade II-III Knee Osteoarthritis? A Prospective Study. Adv. Ortop. 2023, 2023, 1868943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellular Matrix®. Available online: https://www.regenlab.com/products/cellular-matrix/ (accessed on June 5, 2024).

- Saiz, L.C.; Erviti, J.; Learche, L.; Gutiérrez-Valencia, M. Restoring Study PRGF: a randomized clinical trial on plasma rich in growth factors for knee osteoarthritis. Trials 2023, 24, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fuertes, J.; Arias-Fernandez, T.; Acebes-Huerta, A.; Alvarez-Rico, D.; Gutierrez, L. Clinical Response After Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis With a Standardized, Closed-System, Low-Cost Platelet-Rich Plasma Product. 1-Year Outcomes. Orthop J Sports Med, 2022; 10, 3, 23259671221076496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumaran, A.J.; Deveza, L.A.; Atukorala, I.; Hunter, D.J. Assessment of Pain in Osteoarthritis of the Knee. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cedraschi, C.; Delézay, S.; Marty, M.; Berenbaum, F.; Bouhassira, D.; Henrotin, Y.; Laroche, F.; Perrot, S. "Let's talk about OA pain": a qualitative analysis of the perceptions of people suffering from OA. Towards the development of a specific pain OA-Related questionnaire, the Osteoarthritis Symptom Inventory Scale (OASIS). PLoS One, 2013; 8, 11, e79988. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, V.; Anand, C.; Della Paqua, O. Clinical Assessment of Osteoarthritis Pain: Contemporary Scenario, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Pain Ther 2024, 13, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.A.; Rosenthal, R. Choosing between random effects models in meta-analysis: Units of analysis and the generalizability of obtained results. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2018, 12, e12414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Rincón, D.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Botella, J.; Suero, M. . Heterogeneity estimation in meta-analysis of standardized mean differences when the distribution of random effects departs from normal: A Monte Carlo simulation study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2023, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Combining estimators in interlaboratory studies and meta-analyses. Res Syn Meth. 2023, 14(3), 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hönekopp, J.; Linden, A.H. Heterogeneity estimates in a biased world. PLoS One 2022, 17(2), e0262809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felson, D.T. Bias in meta-analytic research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1992, 45(8), 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañez-Heredia, E.; Irízar, S.; Huertas, P.J.; Otero, E.; del Valle, M.; Prat, I.; Díaz-Gallardo, M.S.; Perán, M.; Marchal, J.A.; del Carmen Hernandez-Lamas, M. Intra-Articular Injections of Platelet-Rich Plasma versus Hyaluronic Acid in the Treatment of Osteoarthritic Knee Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial in the Context of the Spanish National Health Care System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17(7), 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Huang, H.; Pan, J.; Lin, J.; Zeng, L.; Liang, G.; Yang, W.; Liu, J. . Meta-analysis Comparing Platelet-Rich Plasma vs Hyaluronic Acid Injection in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Pain Medicine 2019, 20(7), 1418–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.Z.; Nie, M.J.; Zhao, J.Z.; Zhang, G.C.; Zhng, O.; Wang, B. Platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. JOSR 2020, 15, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, T.; Gao, Y.; Ni, J. Efficacy and safety of platelet-rich plasma combined with hyaluronic acid versus platelet-rich plasma alone for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JOSR 2022, 17, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jin, S.; Yao, Y.; He, S.; He, J. Comparison of clinical efficiency between intra-articular injection of platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronic acid for osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2023, 15, 1759720X231157043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, A.; Khan, I.; Tiwari. S. Navigating the treatment landscape: Choosing between platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and hyaluronic acid (HA) for knee osteoarthritis management – A narrative review. JOREP 2024, 3, 100248. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK, 2019.

- R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. (https://www.R-project.org/).

- Alston, J.M.; Rick, J.A. A Beginner's Guide to Conducting Reproducible Research. Bull. Ecol. Soc. Am. 2021, 102(2), e01801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castilla, B.; Jamshidi, L.; Declercq, L.; Beretvas, S.N.; Onghena, P.; Van den Noortgate, W. The application of meta-analytic (multi-level) models with multiple random effects: A systematic review. Behav Res 2020, 52, 2031–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. 2023. Stata 18 Meta-Analysis Reference Manual. Stata Press, College Station, TX, USA.

- Shi, L.; Lin, L. The trim-and-fill method for publication bias: practical guidelines and recommendations based on a large database of meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98(23), e15987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajeunesse, M.J. Facilitating systematic reviews, data extraction, and meta-analysis with the metagear package for R. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2016, 7, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2022, 18(2), e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasey, J.O. (2016) PRISMAstatement: Plot Flow Charts According to the "PRISMA" Statement. R package version 1.1.1 (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/PRISMAstatement).

- RStudio Team (2020). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA. (http://www.rstudio.com/).

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 2010, 36(3), 1–48. (https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03). [CrossRef]

- Pustejovsky, J. (2023). clubSandwich: Cluster-Robust (Sandwich) Variance Estimators with Small-Sample Corrections. R package version 0.5.10. (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=clubSandwich).

- Lakens, D. Equivalence tests: A practical primer for t-tests, correlations, and meta-analyses. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2017, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- compute.es. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/compute.es/index.html (accessed on May 2, 2024).

- Ben-Shachar, M.S.; Lüdecke, D.; Makowski, D. effectsize: Estimation of Effect Size Indices and Standardized Parameters. J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5(56), 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdecke, D. (2019). esc: Effect Size Computation for Meta Analysis (Version 0.5.1). (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=esc).

- Barbone, J.M.; Garbuszus J.M. (2024). openxlsx2: Read, Write and Edit 'xlsx' Files. R package version 1.7 (https://janmarvin.github.io/openxlsx2/).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK, 2019.

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V. Effect sizes for meta-analysis. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, 3rd ed.; Cooper, H., Hedges, L.V., Valentine, J.C., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, USA, 2019; pp. 207–243.

- Ahn, S.; Fessler, J.A. Standard Errors of Mean, Variance, and Standard Deviation Estimators. Technical Report, 2003, EECS Department, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. (https://web.eecs.umich.edu/~fessler/papers/files/tr/stderr.pdf).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, USA, 1988; pp. 24–27.

- Pereira, T.V.; Jüni, P.; Saadat, P.; Xing, D.; Yao, L.; Bobos, P.; Agarwal, A.; Hincapié, C.A.; da Costa, B.R. . Viscosupplementation for knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 378, e069722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Chronological order | Study | Narrative outcomes of compared treatments from the perspective of their inclusion in the meta-analysis / meta-regression investigation |

| 1. | (Filardo, 2015) | No superiority of PRP treatment over viscosupplementation. |

| 2. | (Cole, 2016) | No substantial difference between PRP and HA treatments in terms of the pain score on the WOMAC pain subscale. |

| 3. | (Duymus, 2017) | PRP is more successful than HA in the treatment of mild to moderate KOA. |

| 4. | (Huang, 2019) | PRP performs better than HA in the early stages of KOA. |

| 5. | (Tavassoli, 2019) | PRP is twice as effective in reducing pain as compared to HA, but after two injections at three-week interval. |

| 6. | (Park, 2021) | PRP acts significantly better in reducing KOA pain, even six months after the injection, when the viscosupplementation effect decreases. |

| 7. | (Ciapini, 2023) | The combination of PRP and HA outperforms treatment with HA alone, in KOA. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).