1. Introduction

Autonomous ships are defined as ships that can operate independently of interaction with humans to a certain degree. According to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) [

1], the international shipping’s global regulatory body, such degrees of autonomy are defined as follows:

Degree 1: Ship with automated processes and decision support. The seafarers are on board to operate and control shipboard systems and functions. Some operations may be automated and at times be unsupervised, but with seafarers on board ready to take control;

Degree 2: Remotely controlled ship with seafarers on board. The ship is controlled and operated from another location. Seafarers are available on board to take control and operate the shipboard systems if needed;

Degree 3: Remotely controlled ship without seafarers on board. The ship is controlled and operated from another location. There are no seafarers on board;

Degree 4: Fully autonomous ship. The ship’s operating system can make decisions and determine actions by itself without human intervention.

Depending on the degree of autonomy, autonomous ships can offer considerable benefits in terms of safety, efficiency, and improved operation. However, as a novel presence in the global maritime industry (Degree 3 and Degree 4 are not expected until the 2030s and 2040s), they face significant cybersecurity issues. Addressing potential vulnerabilities to cyberattacks and ensuring that robust cybersecurity measures are in place is important to prevent any unauthorised access or manipulation of the ship’s systems.

The cyberattack surface of autonomous vessels is closely related to the level of autonomy, since the attack surface may vary with the complexity of the number of systems to control and monitor the vessels. Although the cyberattack surface is not well-defined yet, it might consist of attacks aiming at intercepting and manipulating communications or on-board IoT devices, attacks on ICT systems (on-board or remote), attacks on AI/ML-based systems used for autonomous operations or even physical attacks aiming at taking control of the uncrewed vessel.

In this paper, we propose an approach to secure the communication channel between the Shore Control Centre and the vessel, as well as the underlying digital infrastructure in charge of data collection, storage, and processing. More in detail, the proposed approach relies on IEC 63173-2 SECOM standard [

2] for securing the communication channel by implementing cryptography techniques, including a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) and key exchange mechanisms. The protocol ensures end-to-end data integrity, data confidentiality, and authentication processes. The digital infrastructure, deployed in the Livorno seaport, is responsible for hosting the SCC application. Therefore, a combination of the Deep Auto-Encoder and Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering (HD-DNCAE [

3]) ML-based algorithms was developed for anomaly detection conforming with the zero-touch approach. The ICT Prototyping Framework [

4] was adopted and used as a reference architecture and framework for the development and deployment of the components of the autonomous shipping application used for the experimental validation of the proposed approach.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 addresses relevant related work; Section 3 describes the reference architecture used for the application development as well as the application itself; Section 4 is focused on the SECOM standard by describing how it was applied to the considered scenario; Section 5 describes ML-algorithms and how they were applied to detect anomalies within the underlying digital infrastructure; in Section 6 experimental setup and performance evaluation are described; finally, Section 7 presents a discussion of the main findings of the paper and its conclusions.

2. Related Works

Anomaly detection within the maritime domain has been researched through the use of Automatic Identification System (AIS) data, cloud-based frameworks, and ML-based techniques to enhance the level of security and situational awareness in the maritime environment.

Wolsing et al. (2022) [

5] made note that the methods for detecting anomalies in the AIS tracks are course deviation and unexpected port arrivals, a feature for showing suspicious operations and keeping the maritime domain safe. Recently, Nguyen et al. (2024) [

3] proposed an approach for network intrusion detection using deep autoencoders in a Deep Nested Clustering Autoencoder (DNCAE) model to enhance anomaly detection through the learning of a better representation of normal network data in latent space and creating tighter regions of clusters using the K-means clustering technique.

Kim et al. (2021) [

6] conducted research for the detection of sensor data anomalies from maritime engines. They used ensemble learning techniques to combine various machine learning models to increase the overall accuracy and robustness of the developed anomaly detection system, especially in accurately identifying network intrusion among IT systems used in the maritime industry.

Farahnakian et al. (2023) [

7] demonstrated that the K-means clustering method was able to effectively detect ships or those sets of vessels that turn off the AIS transceivers to perform illegal activities. Balduzzi and Pasta (2014)[

8] conducted a security evaluation of the AIS implementations and communication protocols specifications by identifying a set of threats related to both the software and the hardware equipment such as ship spoofing, hijacking or availability disruption (e.g., frequency hopping, timing attacks or slot starvation). Zhang et al. (2022) [

9] proposed a blockchain-based architecture with a reputation voting mechanism for making the consensus process able to improve anti-attack capabilities. The proposed mutual authentication scheme was validated through simulation studies, which phase out the performance benefits in terms of data integrity and confidentiality. Furthermore, Chung et al. (2018) [

10] proposed a route plan exchange scheme based on a blockchain, pointing out the need for a distributed PKI for the port community actors to guarantee a secure information exchange mechanism.

These studies demonstrate the need for appropriate security measures for protecting and securing both the autonomous ships and the digital infrastructures they rely on for communication and data exchange.

3. The Reference Architecture

The Port Authority of Livorno has invested in the standardisation of an ICT reference stack structured as a private cloud, as described in [

4]. The infrastructure allows the development of Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) and Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) functions in the shape of microservices and exposes them through a standard set of APIs for the development of smart applications. Network and computing resources are organised in tenants, serving end users according to their needs. We relied on the above-mentioned architecture for the implementation, validation and development of the Shore Control Centre application as well as of the ML-based algorithms, as explained in the following sections.

3.1. The Shore Control Centre (SCC)

In 2006 the Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) first brought to attention the concept of e-navigation and, since then, has been coordinating the work on the development of a strategy with active participation from relevant IMO sub-committees, member states, international organisations (e.g. IALA and IHO) and industry representatives. E-navigation ([

11]) is the harmonised collection, integration, exchange, presentation and analysis of marine information on board and ashore by electronic means to enhance berth-to-berth navigation and related services for safety and security at sea and protection of the marine environment. The standardisation process will follow high-level directives for

three invariants: Remote Operations Centre (ROC) functionalities, ship assets for a digital ship and the seaport physical/digital infrastructure.

The vessels interact with the ports offering and consuming a wide range of digital services like functionalities exposed by the Port Community Systems (PCSs) and Terminal Operating Systems (TOCs) and representing the

Day X Maritime Services [

12] such as:

Real-time vessel tracking and monitoring in deep sea sailing and port waters;

Plans for operating the vessel, updated according to changes and feedback;

Vessel Collision Avoidance (e.g., early detection of dangerous situations and recalculation of the best path for the vessel);

Vessel Arrival Slot Management (e.g., Just-In-Time arrival, pre-booking of berths and yard resources, customs pre-clearing, etc.);

Calculation and measurement of pollution levels (e.g., COx and noise) and changes to the routing plan of the vessel;

Containerised and general cargo pervasive monitoring and control in port areas and along the logistics chain.

The Remote Operations Centre is supposed to be an infrastructure placed ashore (hence why we refer to it as the Shore Control Centre), accessible and fully integrated with the port digital infrastructure and able to combine the information from the land side with the ones coming from the vessel to enable all the required services and functionalities for the monitoring and the direct control of the ship, the handling of communication, the planning and the organisation of activities in the port area, and the production of documentation.

We implemented and deployed a prototype of the SCC at the Joint Laboratory for Seaports (JLAB-Ports [

13]) in Livorno, in the context of the 5G MASS project [

14] activities. The SCC is structured as a set of applications running as Software-as-a-Service in a private cloud. The architecture includes an Authentication and Authorisation server to monitor and manage access to the service through user profiling. The communication between the SCC and the ship approaching the port is guaranteed by a 5G millimetre-wave private network in a stand-alone configuration operating in the n258 frequency band (26 GHz) with a nominal bandwidth of up to 10 Gbps. The 5G Core Network is hosted at the JLab-Ports premises, in Livorno.

The applications composing the Shore Control Centre are based on the real-time availability of the information coming from the ship to the shore and vice versa, which is exchanged through the 5G private network. In particular, the SCC makes use of port-related data and a snapshot of the seaport area through the high-definition monitoring network (10 cameras) and the data coming from the sensor network of the Port of Livorno (bathymetric probe, weather stations, anemometers, current meters, wave meters, noise and environmental sensors). Moreover, the SCC can exploit the information coming from the shipboard as well as from the sensors installed on board (e.g., cameras and Light Detection and Ranging sensors - LIDARs). The exact positioning of the ship (order of centimetres) is guaranteed by the presence of a Real-Time Kinematics (RTK) network.

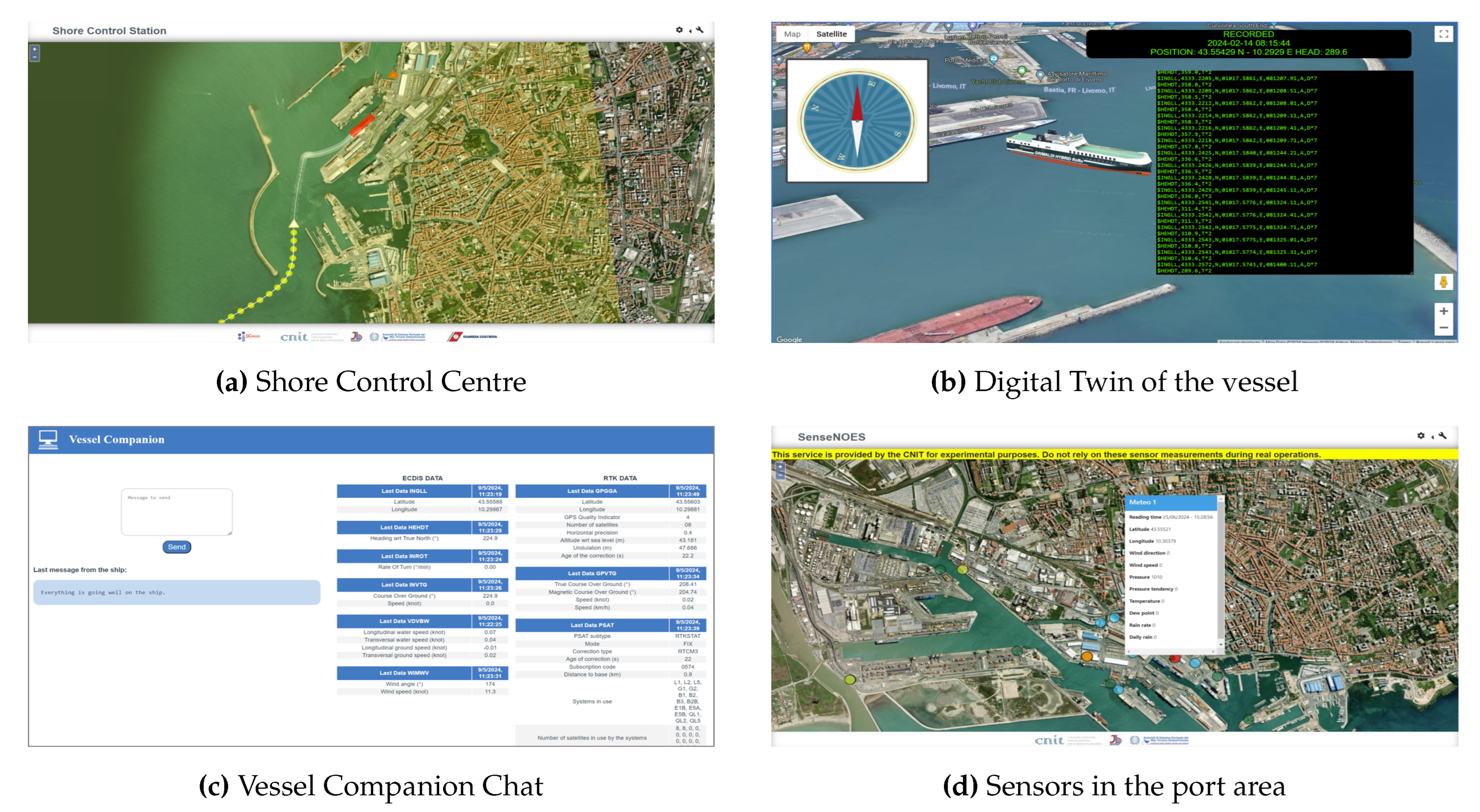

Figure 1 shows the main applications composing the SCC that enable the control and monitoring of the ship while approaching the berth as well as the current weather and marine conditions to detect potential security and safety issues and support the risk assessment based on IMO/EU standards. The

Shore Control Station application (

Figure 1) is a 2D map visualising the ships within the port area and the ship that is entering the port. The application shows the trajectory of the ship and includes a real-time computation of the optimal route that a given ship should follow to reach the assigned berth. The application is also able to visualise eventual alerts and alarms that may arise during the manoeuvre in case the ship deviates from the optimal route.

Figure 1 shows the

Digital Twin of the ship on a 3D map during the approach to the berth together with the information coming from the shipboard in real-time, e.g. the NMEA 0183 [

15] sentences shown on the Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS) on board the ship. The

Vessel Companion Chat (

Figure 1) has a counterpart running on a portable device used on board the ship and allows the real-time exchange of information from the ship to the shore and vice versa, together with the visualisation on the SCC of information coming from the ship side. Finally,

Figure 1 shows the

SenseNOES application that allows the visualisation of all the sensors installed in the port area for monitoring purposes, including their position and the last reading they produced.

4. The SECOM Standard

The increase in reliance on digital systems in the maritime domain has paved the way for a wide range of cyberattacks. These cyberattacks can lead to compromised operational security, potential disruptions to business operations, and data breaches. One key aspect in mitigating these concerns is the adoption of standardised procedures and protocols for secure data transmission and communication, such as the SECOM standard [

2]. IEC 63173-2 SECOM is an international standard defining a secure communication protocol between a ship and an SCC, which provides capabilities for secure data exchange with technical services that are defined by IALA [

16] and partly included in the IHO S-100 standard [

17]. The standard includes information service interfaces (APIs) for the data exchange, and information security measures using a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI), covering communication channel security and data protection aspects. The exchange of messages between the ship and the SCC relies on IP-based web services.

The SECOM components provide measures to meet the security requirements of the applications such as data authentication and integrity, service authentication and mutual TLS, data confidentiality and secure communication channels, access control, and identification through a common registry for unique identities.

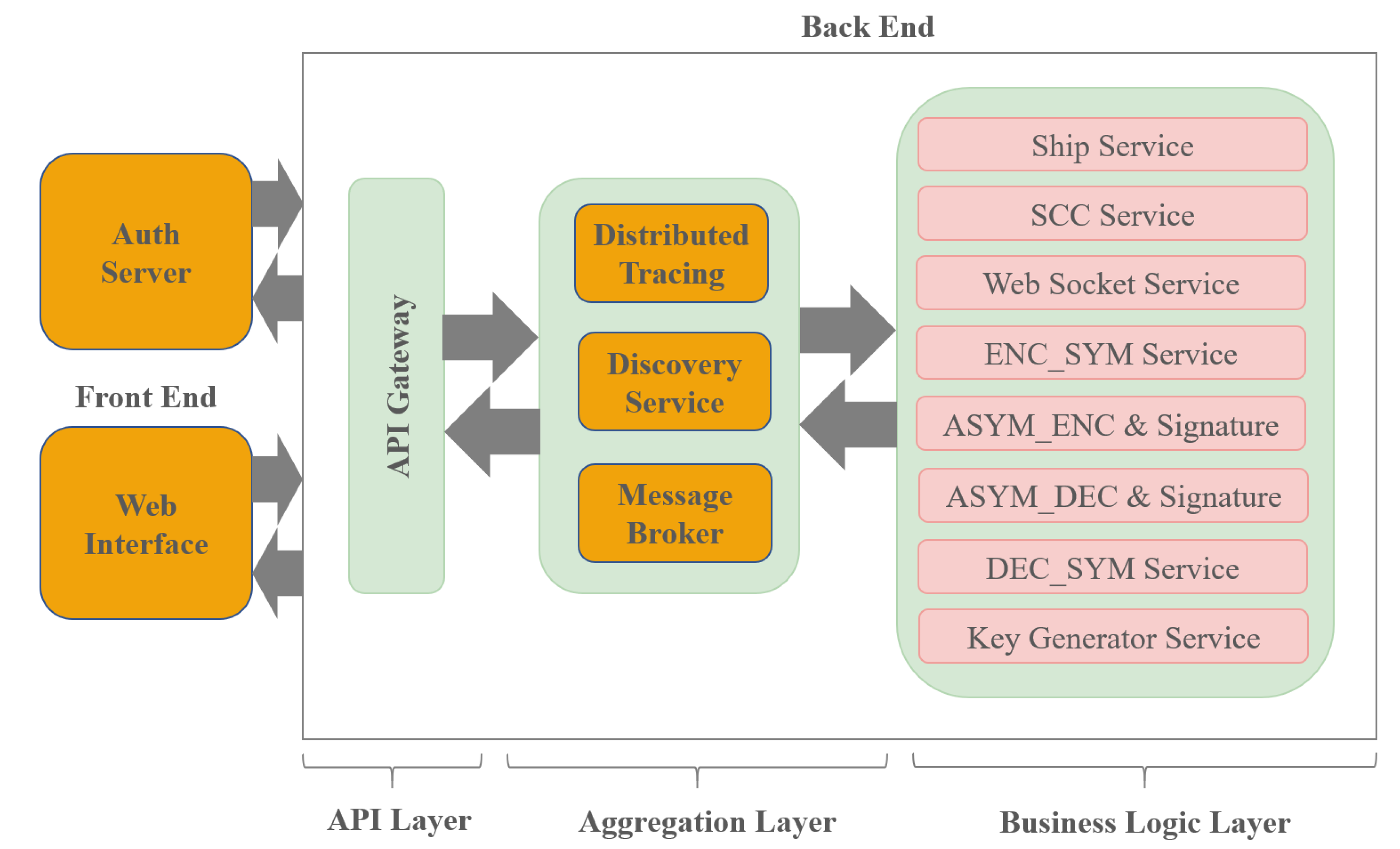

Due to the complexity of maritime networks, in addition to a secure communication protocol capability between the ship and SCC, there is a need for a framework that can properly address scalability as well as fault tolerance-related aspects. Hence, the SECOM standard is implemented relying on a microservice architecture (namely MSA-based SECOM). The MSA-based SECOM is deployed on the SCC, and it comprises different microservices, as shown in

Figure 2. Some are employed for non-functional requirements, such as the API Gateway, the discovery server, the authentication and authorisation server, the distributed tracing mechanism, the message broker, and the web sockets. Then there is a suite of microservices that are required to implement the SECOM functionalities such as the Symmetric Encryption and Symmetric Decryption, the Asymmetric Encryption and Signature, the Asymmetric Decryption and Signature Verification, the Key Generator and WebSocket. The main purpose of the SECOM standard is to enable the exchange of information that is consistent with the S-100 data model from the ship to the SCC and vice versa in such a way that the security requirements are fulfilled.

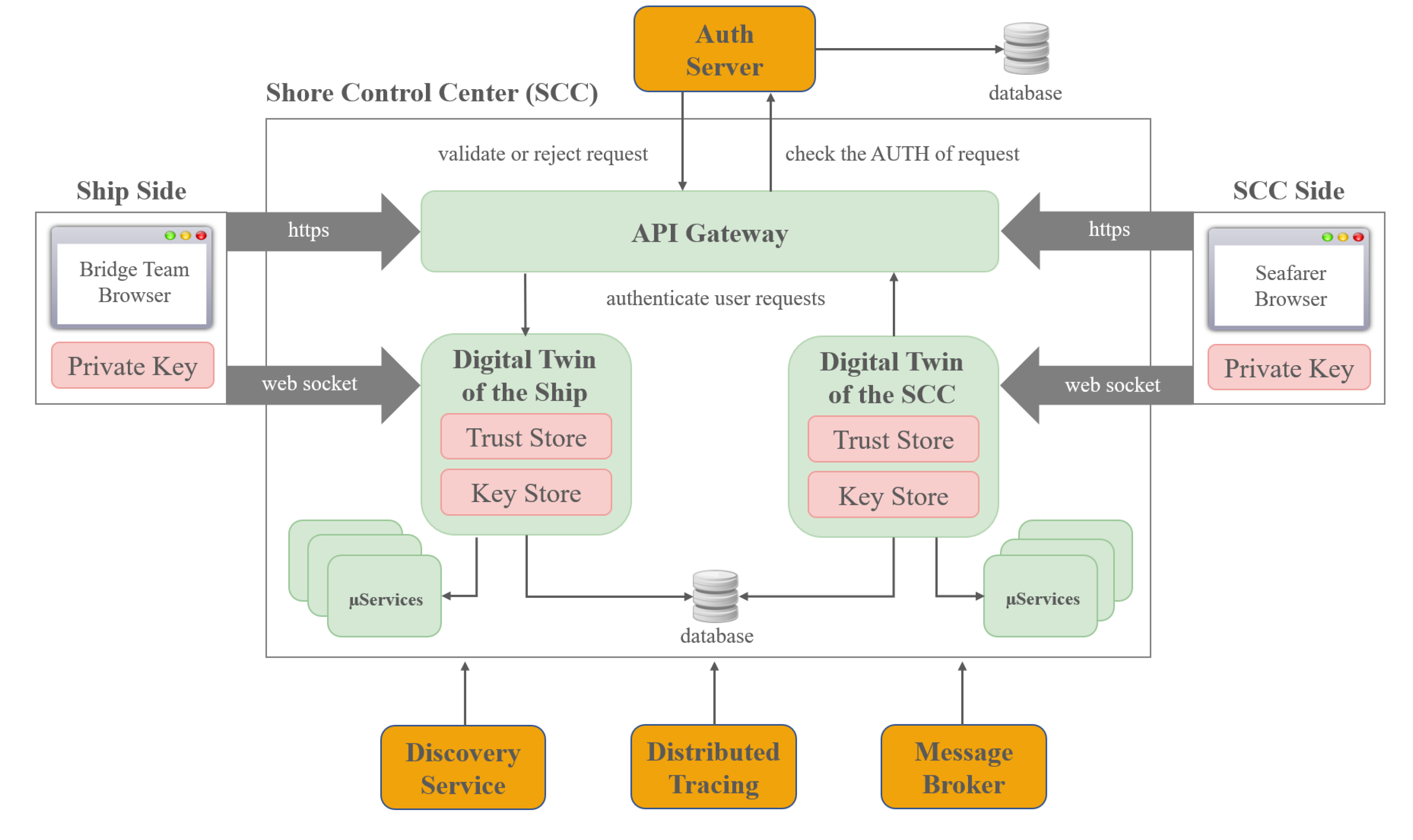

As shown in

Figure 3, the SECOM system architecture has three main blocks: the ship side, the MSA-based SECOM suite and the SCC side. On the ship side, users are connected through a browser and can exploit the functionalities provided by the ship-side microservices. They are provided with a digital certificate and a private key to encrypt messages to be sent to the shore. The SCC operator also has his own certificate and a private key and can send encrypted messages to the ship side.

To achieve the capability of exchanging messages, the ship sends an HTTP request to the API Gateway acting as a proxy. The gateway in turn redirects the request to the authentication server that has to authorise it. If the request is approved, it is redirected to the microservice that allows the ship to establish a WebSocket connection and make a digital copy of all the services on its side. At this point, the microservice starts to interact with the other microservices to finally provide the user with a shared key, enabling end-to-end encryption between the two entities. Having the shared key, the ship sends an encrypted and authenticated message to the SCC. Assuming the ship has undergone the authentication step and has established a WebSocket connection, the ship can receive the messages, verify their authenticity and decrypt them using the shared key.

4.1. Data Integrity and Confidentiality

The data protection scheme of the SECOM standard is provided by a suite of microservices, first generating a shared key between the ship and the SCC, then using this key to encrypt the information and ensure confidentiality by adding a tag for integrity and authenticity of the message. In this schema, each entity authenticates with the authentication server through the API Gateway and then gets an ID token as well as an access token. Then each side establishes a WebSocket with the support of the WebSocket microservice for dual communication between the parties. The ship side first requests to the CA the certificate of the other party, it then requests the Key Generator microservice to generate a pair of Diffie-Hellman (DH) private and public keys. It grabs the public key of the shore side, encrypts the message with its public key, generates a signature with the Asymmetric Encryption and Signature microservice and forwards it to the SCC together with its CA-signed public key. At this point, also the SCC side requests the Key Generator microservice to generate a DH private and public keys pair. First, it retrieves the ship-side certificate from the previous message and verifies and decrypts the received message through the Asymmetric Decryption and Signature Verification microservice. Then the shoreside signs its public key and the message with its private key and forwards it back, concatenating with its certificate. From now on, the SCC can generate the shared key by combining the ship’s public DH key that was received and its generated DH private key, through the Key Generator microservice. Since the ship has also received the message, it first decrypts and verifies it, retrieves the DH public key of the SCC, combines it with its own DH private key, and generates the shared key. At this point, both parties have the same shared key that can be used to encrypt the messages and generate integrity tags to send the information from one side to the other through the Symmetric Encryption microservice. Through these interactions, the message is confidential, and its integrity is guaranteed. The other side uses a Symmetric Decryption microservice to verify the tag and decrypt the message by using the shared key.

To establish a secure communication channel, we have implemented mutual authentication on each side, as both sides act as a service provider and a consumer at the same time. Each microservice has its certificate and private key stored in a key store and a CA certificate in a trust store. Whenever a microservice wants to serve a request, it has to provide the certificate to authenticate itself but, on the other hand, it needs to authenticate the service requester by asking for the certificate and verifying it against the CA certificate in the trust store. This allows to establish a secure communication channel, providing data integrity and confidentiality capabilities.

4.2. Authentication

Similarly to data integrity and confidentiality, in the SECOM implementation the authentication is achieved at three levels: through data protection, the secure communication channel, and the adoption of an authentication and authorization server. Authentication is the process by which a user or service proves to a system its identity. When a user or a service wants to use the SECOM standard, it first has to authenticate itself through the authorization server by providing the credentials and has to obtain an access token for the microservices interfaces. The second level of authentication is through the data protection scheme, with the establishment of the shared key between the ship and the SCC. Parties exchange certificates signed by the CA which is a trusted third party and can verify the authenticity of the messages. Finally, the third level of authentication is achieved through the SECOM secure communication channel, which provides service authentication on top of data integrity and confidentiality. It also provides a secure channel for the authentication of the functionalities exposed by each microservice.

5. Machine Learning Algorithms

As presented in

Section 2, existing Machine Learning algorithms still have some limitations. To overcome such limitations, we propose an approach to integrate HDBSCAN into DNCAE during the clustering of the latent space and label it

HDBSCAN Deep Nested Clustering Auto-Encoder (

HD-DNCAE). Our approach can enjoy the benefits of deep auto-encoders in learning compact and meaningful data representations, where the current cluster configurations can be adapted in the latent space without prior determination of the number of such clusters. This increases not only the ability of the model to capture the underlying structure of data but also its adaptability to changing patterns of the data, which is crucial for network intrusion detection systems in highly dynamic contexts, such as ports.

5.1. Model Architecture

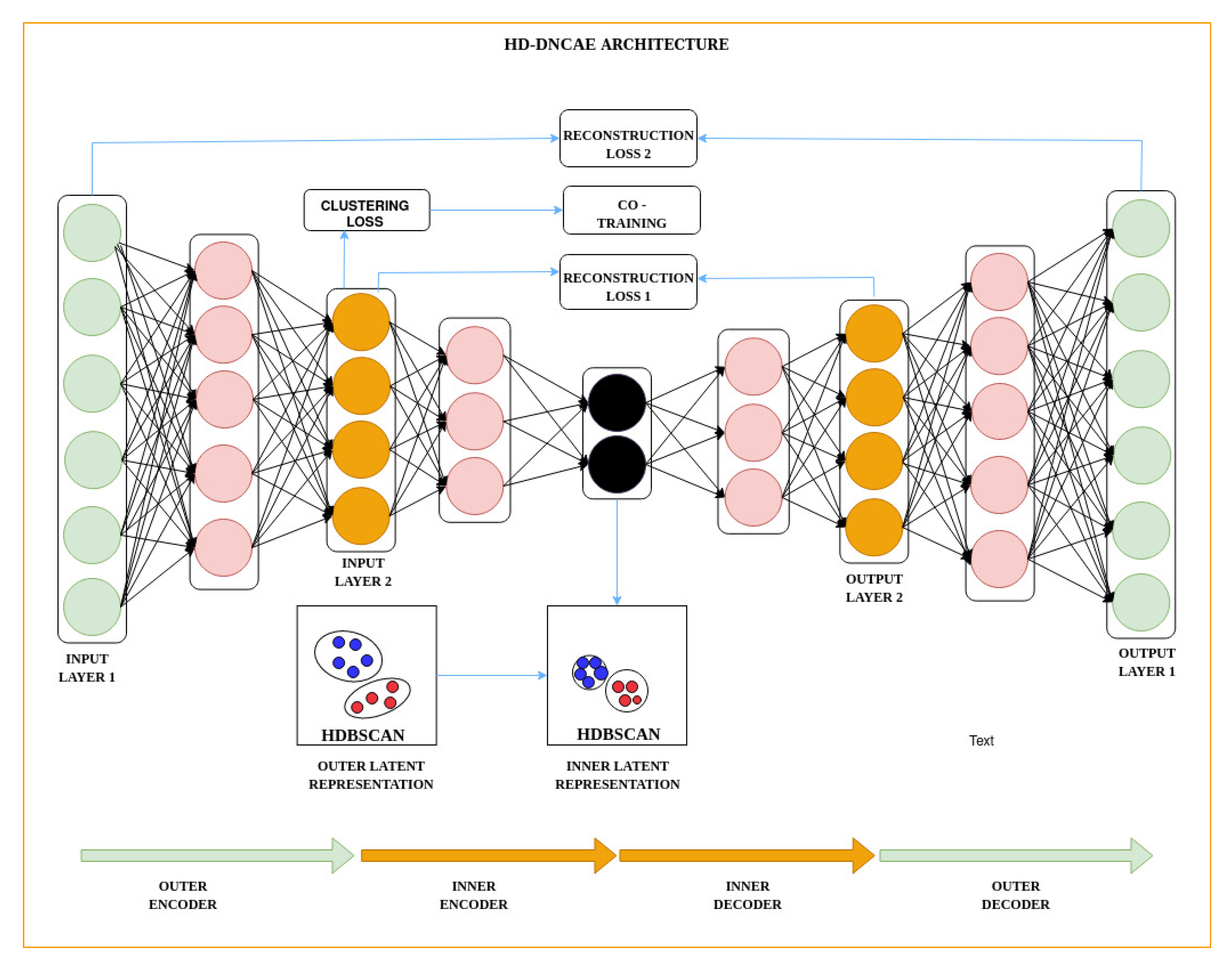

The HD-DNCAE model comprises two main components, as shown in

Figure 4:

Nested Deep Auto-Encoders (DAE): the architecture features an outer and inner Deep Auto-Encoder. The outer DAE first compresses the input data into a latent representation. The compressed latent representation, serving as the input for the inner DAE, is further refined into a more compact latent space. This process of hierarchical feature extraction in such a nested structure is adopted to enrich the capability for models to learn nuanced characteristics of data.

Dynamic Clustering with HDBSCAN: the proposed model embeds the HDBSCAN algorithm in the latent space of the outer DAE. In contrast, HDBSCAN dynamically calculates a derived value from data density for optimized clustering, whereas methods used in DNCAE [

3] require a fixed number of clusters. Because of this result, it comes out as a more flexible and accurate mechanism of anomaly detection. Such an integration allows one to learn from the optimally organized data configuration in the latent space, which has a huge positive effect on improved anomaly detection capability.

5.2. Training and Objective Functions

The model HD-DNCAE is trained using a co-training mechanism with the minimization of a composite objective function that is intended to minimise:

Reconstruction Loss: training both outer and inner DAEs reconstructs the error, restoring input data in the latent spaces with a faithful representation.

Loss from clustering: losses assigned from the HDBSCAN-based algorithm force the model to learn the best pattern of latent features, hence improving the separability between normal and anomalous data.

5.3. Anomaly Detection

In the post-training stage, anomaly detection is carried out by adopting both trained latent representations and clustering configurations. The detection of anomalies uses deviations from normal data patterns, as they have been modelled in the latent spaces with dynamic clustering to add more granularity and point out outliers.

6. Performance Evaluation

6.1. SECOM Implementation and Validation

6.1.1. Experimental Setup

The implementation of each component of the SECOM standard is done using a Javascript framework called Spring Boot [

18]. The framework follows a layered architecture that consists of a presentation layer, a business layer, and a persistence layer running on a 4-core Linux server with 8GB RAM and installed using the JDK (Java development kit), Docker engine and Docker-compose in the Livorno ICT stack.

The proposed SECOM implementation is composed of different microservices organized in three layers: the API access layer, the aggregation layer and the application logic layer. The API access layer includes the Spring Cloud API Gateway [

19] and the Keycloak [

20] server for authentication and authorization. The Aggregation layer includes the Eureka [

21] discovery server, the Kafka [

22] message broker, and the Zipkin [

23] distributed tracing system. Finally, the application logic layer consists of the ship and the SCC microservices as well as of the SECOM security suite e.g., (WebSocket, encryption, decryption, asymmetric encryption and signature creation, asymmetric decryption and signature verification and key generator microservices). All these microservices are working independently and running in their dedicated Docker-containerised environment. To containerize all microservices, we relied on a Maven plugin called JIB [

24]. Then, we added the configuration of each microservice to a docker-compose file to be able to orchestrate the multiple interconnected services in our system implementation. Some of the dependencies used are JCA (Java Cryptographic Cypher) and JSE (Java security), which provide the core security functionalities such as secret key generation, DH public and private key generation and encoding. In addition to these Java libraries, we also used i) Spring Boot dependencies, such as Starter Web and Lombok [

25], which provide necessary components for building web applications using the Spring MVC framework; ii) Web Client dependency for HTTP requests, iii) Kafka dependencies, iv) OAuth2 client and OAuth2 resource server dependencies, which allow the client to interact with the authorization server and v) dependencies for the discovery server registration.

After configuring all this, our main purpose was to generate a shared key (using an authenticated Diffie-Hellman key) to be exchanged among the ship and the SCC for encrypting and sending an authenticated and confidential message over an unsecured public network. To achieve this, the users make a request through the API Gateway and get subscribed to the topics required for the key exchange (functionality provided by the WebSocket microservice). Consequently, it is possible to make a copy (a digital twin) of the ship and SCC microservices. However, this operation is successful only if the users are authenticated and authorized through the Keycloak server and, subsequently, are provided with an ID and an access token accordingly. In addition to the trust and key stores used for establishing the mutual TLS channel between the digital twin of the ship and the SCC microservices, we also prepared certificates and private keys using OpenSSL [

26]. Once a secure communication channel is established, all microservices can interact with the SECOM security suite, synchronously or asynchronously, using the Kafka message broker, and establish a shared key. During this interaction, the Eureka discovery server is used, together with Spring Cloud API Gateway, to discover all the microservices that have been pre-registered, while the routes and interactions among the microservices are traced using Zipkin.

6.1.2. Experimental Results

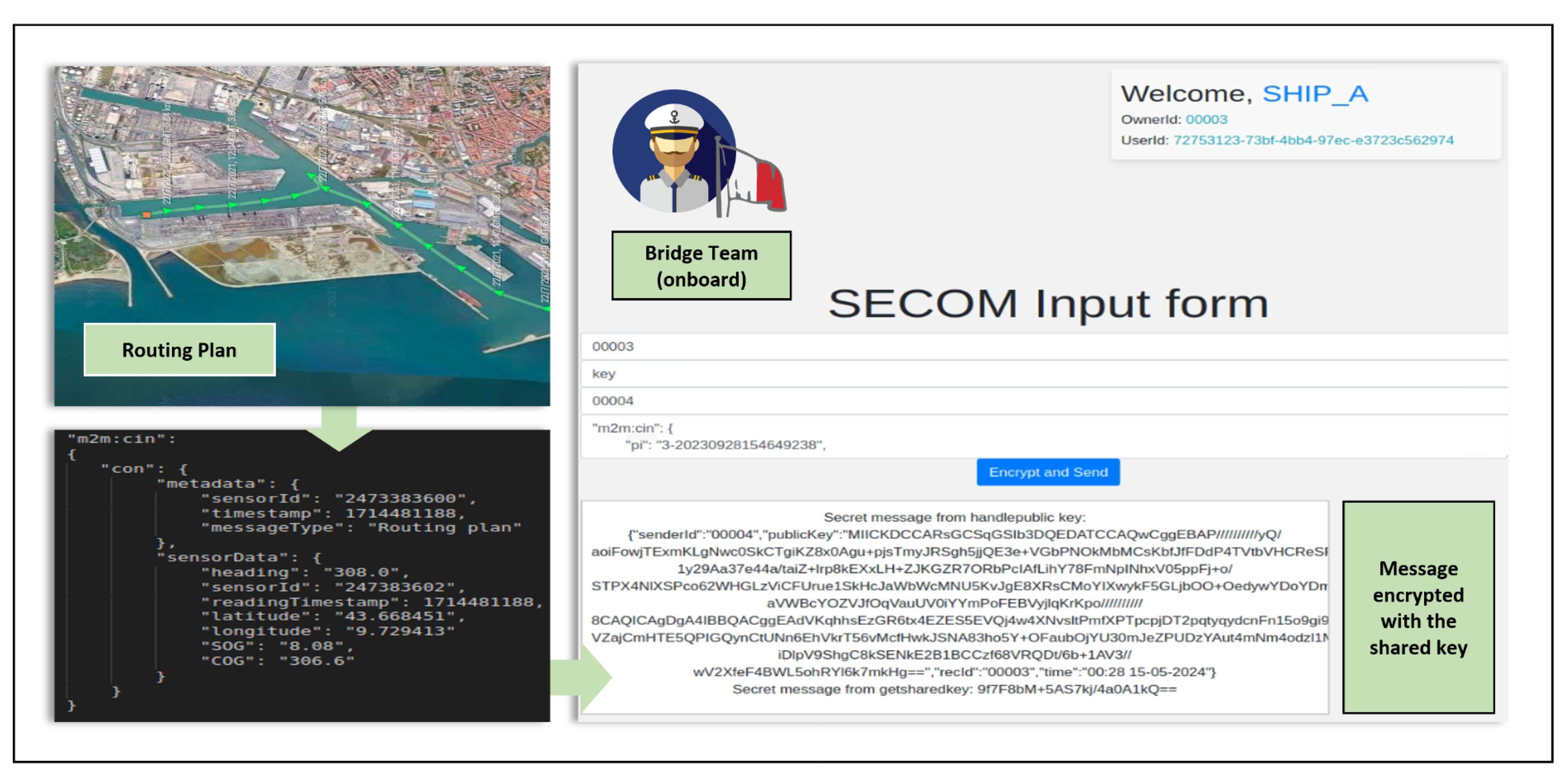

After spinning all the containers using Docker Compose commands, SECOM can be used as a secure infrastructure by the users (from the ship and ashore). Both end users (the bridge team and the seafarers) bootstrap the application and are redirected to the Keycloak login page for authentication. Assuming each user has been authenticated successfully, he is provided with an ID and an access token so that he can use every microservice. After that, users are redirected to the home page of the application. From this point on, each user can establish a shared key when he wants to send a message to the other side. In our case, the bridge team wants to send a sample vessel routing plan to the seafarers, as can be seen in

Figure 5. The same shared key is established in both parties using the Diffie-Hellman key exchange protocol. The bridge team uses this key to encrypt the message, generate a tag, and finally send the message to the seafarers. The seafarers authenticate the tag, decrypt the message, and can view the message in clear text. During the data exchange process, data integrity and confidentiality, as well as service authentication, are guaranteed by the SECOM standard. The implemented system is also fault-tolerant and scalable, since each microservice is independent and can be easily scaled by running multiple instances. On top of this, all the requests can be load-balanced by the API Gateway in case of high naval traffic and traced by Zipkin.

6.2. Machine Learning Algorithms Implementation and Validation

6.2.1. Experimental Setup

The test bed for building the Machine Learning algorithms for anomaly detection consists of both hardware and software configurations. The proposed models were built and tested on a machine with Intel Core i78700 CPU, which operates with 12 cores at a speed of 3.20 GHz, has RAM of 16 GB, and a dedicated Graphical Processing Unit (GPU) of type NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2060 Rev. This setup helps with multitasking, management of our large dataset, and intensive computation that are parallelizable. The operating system of the test bed is Ubuntu 22.04.4 LTS 64-bit; Python3.8 is installed on the OS and Jupyter Notebook [

27] is utilized as a development environment. The libraries used for building the neural network are PyThorch [

28] which helps us utilize the GPU to accelerate the development process and HDBSCAN from Scikit-learn [

29] which is compatible with Python and is used for clustering. In the preprocessing phase, Numpy [

30] and Pandas [

31] were used, while Matplotlib [

32] and Seaborn [

33] were used for plots.

In the training phase, a co-training method is used to train the HD-DNCAE model using only normal data from the dataset. We update the weights and biases of our deep neural network (HD-DNCAE) by using the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) method. The co-training is done in two steps: firstly, the HD-DNCAE is trained to learn the information and meaningful representations in the latent layers of normal data fed into the neural network. After that, the model is used to train simple One-Class Classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) with a variety of kernels (Linear, Poly, RBF and Sigmoid). We also train using Isolation Forest (IF), Local Outlier Factor (LOF), Elliptic Envelope (EP), Centroid (CEN), and Kernel Density Estimation (KDE), classifiers that are chosen based on the work done by Nguyen [

3].

6.2.2. Experimental Results

The data sets used for the evaluation of the proposed algorithm (HD-DNCAE) include benchmark data such as the NSL-KDD [

34], UNSW-NB15 [

35], and CIC-IDS2017 [

36]. The NSL-KDD data set is based on the data captured in the DARPA’98 Intrusion Detection System (IDS) evaluation program and has been the most widely used data set for the evaluation of anomaly detection methods. UNSW-NB15 is a comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems, which contains raw network packets and includes nine different attacks. The CIC-IDS2017 dataset contains benign data and the most up-to-date common attacks, which resemble true real-world data. It also includes the results of the network traffic analysis with labelled flows based on the time stamp, source, and destination IPs, source and destination ports, protocols and attacks. These datasets were used as a baseline for the bench-marking of the outcomes of the proposed model.

Finally, network-related data sets have been collected from the Livorno ICT stack as well as from the underlying machine-to-machine platform (namely Mobius OneM2M [

37]) which is used to collect and store data coming from the IoT monitoring network deployed in Livorno seaport (e.g., weather conditions, noise and pollution levels, etc.). The main parameters that are taken into consideration include IP address and port, protocol, timestamps, flow duration and rate, packet count and length, inter-arrival times and several TCP tags.

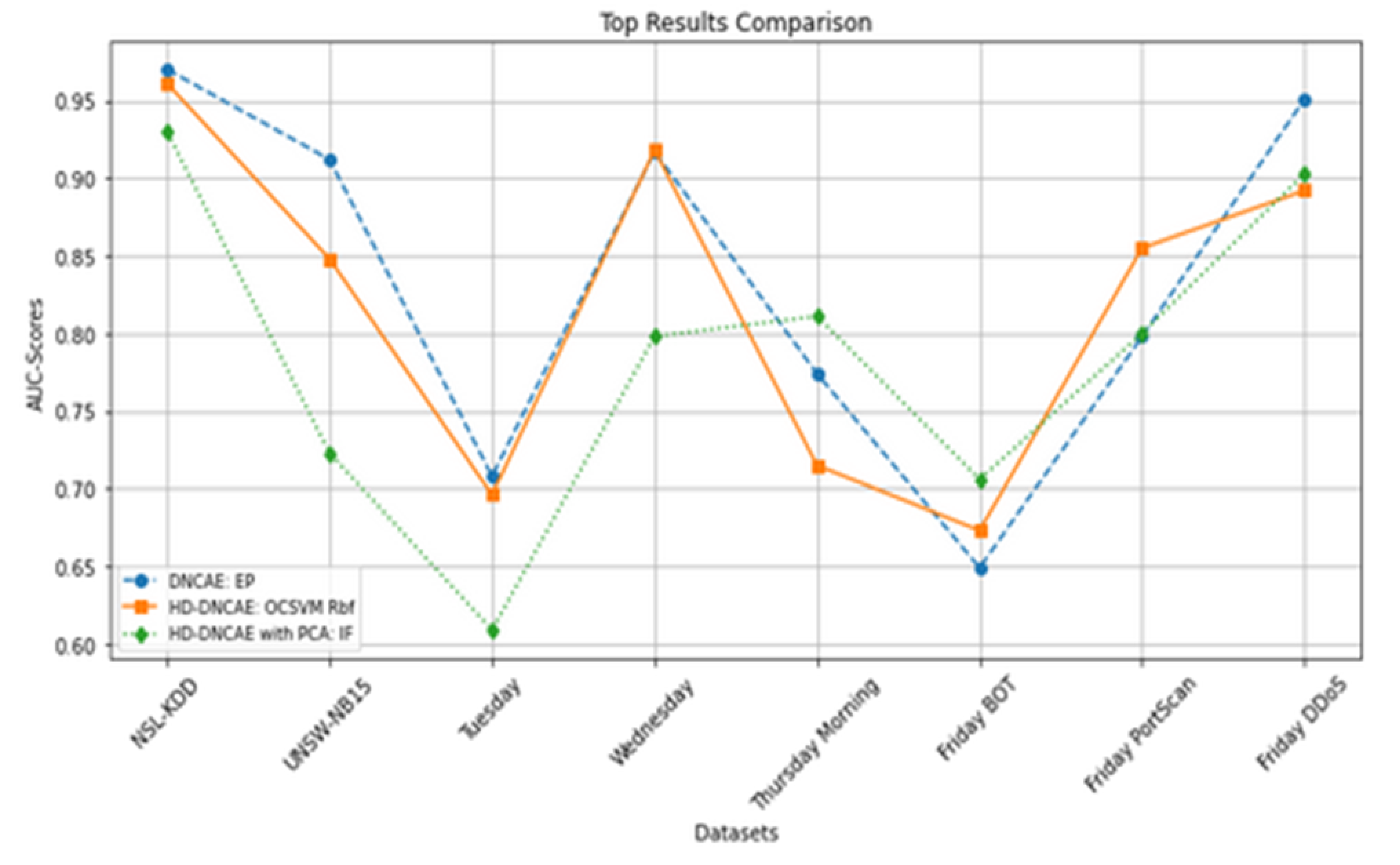

Figure 6 shows the results obtained after running the ML algorithms with the data sets described before. As we can see from the plot, HD-DNCAE performs similarly to DNCAE but does not require setting the number of clusters in advance. This improves the zero-touch approach after our security module has been deployed inside the Livorno reference stack. Another improvement on the part of the classifiers is that the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) performs far better with HD-DNCAE compared with DNCAE. We also tried to apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to our datasets, but this did not improve the learning of the compact clusters within the latent space.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we addressed security challenges related to the maritime domain by implementing the SECOM standard for securing the communication channel between the ship and the Shore Control Centre and by testing the Machine Learning algorithms for anomaly detection using the ICT reference stack of the Port of Livorno.

The proposed implementation of the SECOM standard, using a scalable microservice architecture, provides data confidentiality and data integrity while the scalability and robustness of the implementation addresses the existing security challenges that are faced in the context of the IHO S-100 [

17] framework. On one side, our implementation provides a mutual authentication procedure for the authentication among microservices. On the other side, the implementation provides the capability to generate and exchange shared keys among the parties so that the information exchanged through untrusted public networks can be decrypted only by the recipients accordingly. Finally, we validated the proposed solution in the context of the 5G MASS project [

14] funded by the European Space Agency as part of the on-field trial activities in the Livorno seaport.

Furthermore, the paper assessed the state of the art of anomaly detection in private cloud environments for maritime services with the introduction of HDBSCAN support to the DNCAE model. This enabled the expansion of the ICT reference stack of the Port of Livorno to support the anomaly detection module and the implementation of a misbehaviour detection algorithm that is not brittle against the constantly evolving nature of cyberthreats. The inclusion of HDBSCAN led to better clustering of data, where the number of clusters did not have to be predefined by enhancing the adaptability and precision in the identification of threats. In this paper, we tested the proposed HD-DNCAE model with benchmark datasets coming from the ICT reference stack in Livorno seaport and attained a high score of Area Under the Curve (AUC). The model turned out to be robust, and the results further attested to the competency of the model. In this direction, the result of this work revealed the practical applicability of the model for obtaining relevant improvements in the cybersecurity-related aspects applied to the maritime domain.

References

- MSC.1/Circ. 1638 - OUTCOME OF THE REGULATORY SCOPING EXERCISE FOR THE USE OF MARITIME AUTONOMOUS SURFACE SHIPS - MASS, 2021, https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/PublishingImages/Pages/Autonomous-shipping/MSC.1-Circ.1638%20-%20Outcome%20Of%20The%20Regulatory%20Scoping%20ExerciseFor%20The%20Use%20Of%20Maritime%20Autonomous%20Surface%20Ships...%20(Secretariat).pdf.

- IEC 63173-2:2022: Maritime navigation and radiocommunication equipment and systems - Data interfaces - Part 2: Secure communication between ship and shore (SECOM) Maritime navigation and radiocommunication equipment and systems - Data interfaces - Part 2: Secure communication between ship and shore (SECOM).

- Nguyen, V. Q.; Ngo, T. L.; Nguyen, L. M.; Nguyen, V. H.; Shone, N. Deep Nested Clustering Auto-Encoder for Anomaly-Based Network Intrusion Detection. 2023 RIVF International Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies (RIVF), , Hanoi,Vietnam, 2023, pp.289-294. [CrossRef]

- Barasti, D. S: An ICT Prototyping Framework for the “Port of the Future”, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wolsing, K.; Roepert, L.; Bauer, J.; Wehrle, K. Anomaly Detection in Maritime AIS Tracks: A Review of Recent Approaches. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Antariksa, G.; Handayani, M.P.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. Explainable Anomaly Detection Framework for Maritime Main Engine Sensor Data. Sensors 2021, 21, 5200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahnakian, F.; Nicolas, F.; Nevalainen, P.; Sheikh, J.; Heikkonen, J.; Raduly Baka, C. 2023, https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/15/6/1477#.

- Balduzzi, M.; Wilhoit, K.; Pasta, A. A Security Evaluation of AIS 2014 https://documents.trendmicro.com/assets/white_papers/wp-a-security-evaluation-of-ais.pdf.

- Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Singh Aujla, G.; Jindal, A.; Al Otaibi, Y. A Blockchain-Based Authentication Scheme and Secure Architecture for IoT-Enabled Maritime Transportation Systems 2022, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9745459.

- Chung, D.; Sook Jeon, H. Route Plan Exchange Scheme Based on Block Chain 2018, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8436761.

- MSC 85/26/Add.1, annex 20 - Strategy for the development and implementation of e-navigation, 2020 https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Safety/Documents/enavigation/MSC%2085%20-%20annex%2020%20-%20Strategy%20for%20the%20development%20and%20implementation%20of%20e-nav.

- Pagano, P. , Antonelli, S., Tardo, A. C-Ports: A proposal for a comprehensive standardization and implementation plan of digital services offered by the "Port of the Future". ArXiv, 2021. [CrossRef]

- JLab website. https://jlab-ports.cnit.it/.

- 5G-assisted Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship - 5G MASS. https://jlab-ports.cnit.it/activity/.

- The NMEA standard. https://www.nmea.org/.

- IALA. https://www.iala-aism.org/about-iala/.

- S-100 products. https://iho.int/en/standards-and-specifications.

- Spring Boot. https://spring.io/projects/spring-boot.

- Spring Cloud Gateway. https://spring.io/projects/spring-cloud-gateway.

- Open Source Identity and Access Management - Keycloak. https://www.keycloak.org/.

- Service Registration and Discovery - Netflix Eureka service registry. https://spring.io/guides/gs/service-registration-and-discovery.

- Open Source Distributed Event Streaming Platform - Apache Kafka. https://kafka.apache.org.

- Distributed Tracing System - Zipkin. https://zipkin.io/.

- Maven Plugin for Building Container Images - JIB. https://mvnrepository.com/artifact/com.google.cloud.tools/jib-maven-plugin.

- JAVA Library - Lombok. https://projectlombok.org/n.

- Cryptography and SSL-TLS Toolkit - OpenSSL. https://www.openssl.org/.

- Jupiter Notebook. https://jupyter.org/.

- PyTorch. https://pytorch.org/.

- HDBSCAN algorithm in Scikit-learn. https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.cluster.HDBSCAN.html.

- NumPy. https://numpy.org/.

- Pandas. https://pandas.pydata.org/.

- Matplotlib. https://matplotlib.org/.

- Seaborn. https://seaborn.pydata.org/.

- NSL-KDD Datasets. https://github.com/Mamcose/NSL-KDD-Network-Intrusion-Detection.

- UNSW-NB15 Datasets. https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/unsw-nb15-dataset.

- CIC-IDS2017 Datasets. https://github.com/mahendradata/cicids2017-ml.

- Mobius OneM2M Standard Platform. https://github.com/IoTKETI/Mobius.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).