Submitted:

27 June 2024

Posted:

27 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Chemicals

2.1.2. Plant Material

2.1.3. Grinding of Dry Plant Material

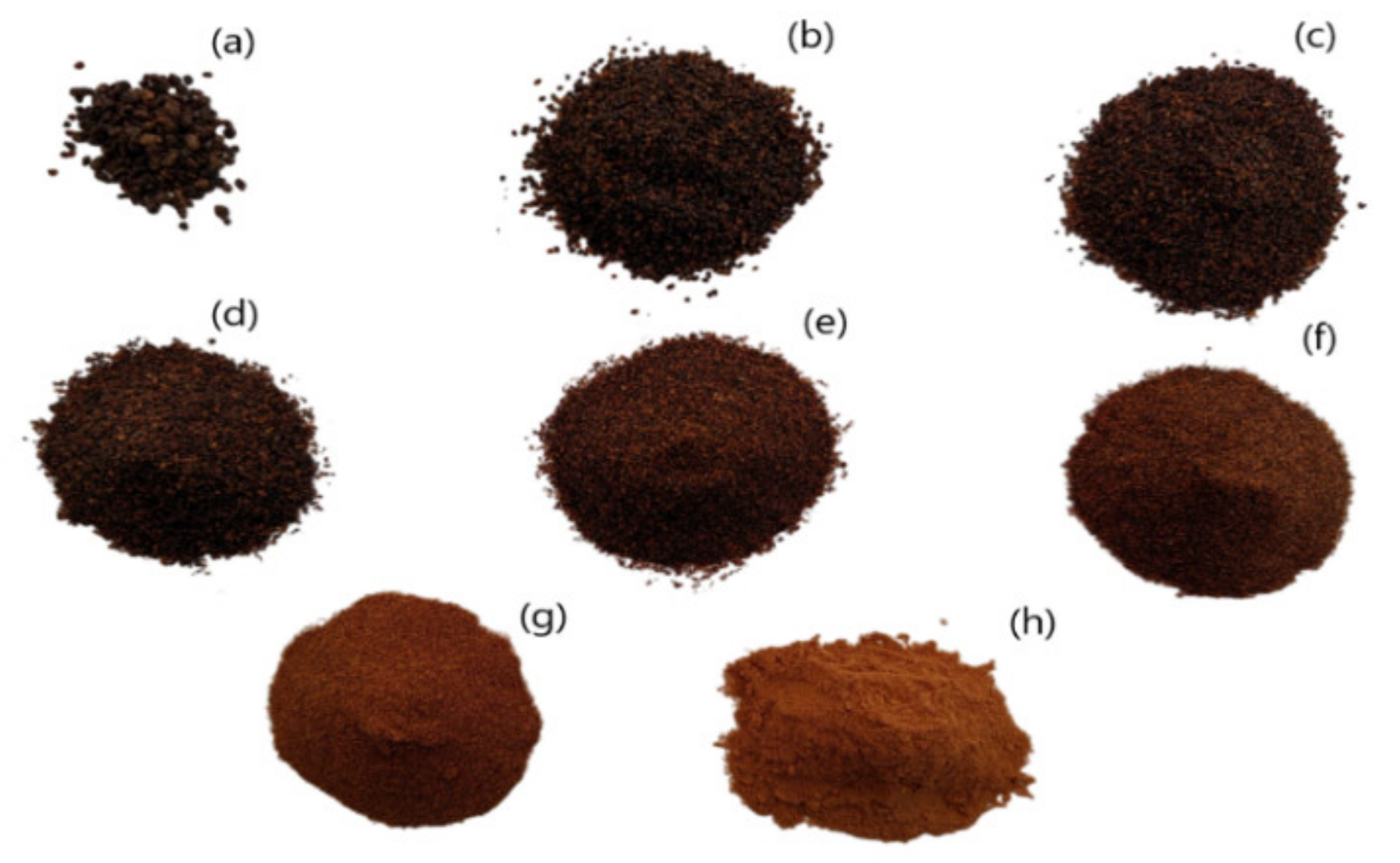

2.1.4. Sieving Plant Powder

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Moisture Content and Water Activity

2.2.2. Hydration Properties

2.2.3. Preparation of Extracts and Analysis of the Absorption Spectrum

2.2.4. Total Phenolic Content

2.2.5. Antioxidant Activity: DPPH Test

2.2.6. Proteins by the Lowry Method

2.2.7. Carbohydrates by Dinitrosalicylic Acid (DNS) Technique

2.2.8. Amount of Vitamin C by the Iodometric Method

3. Results

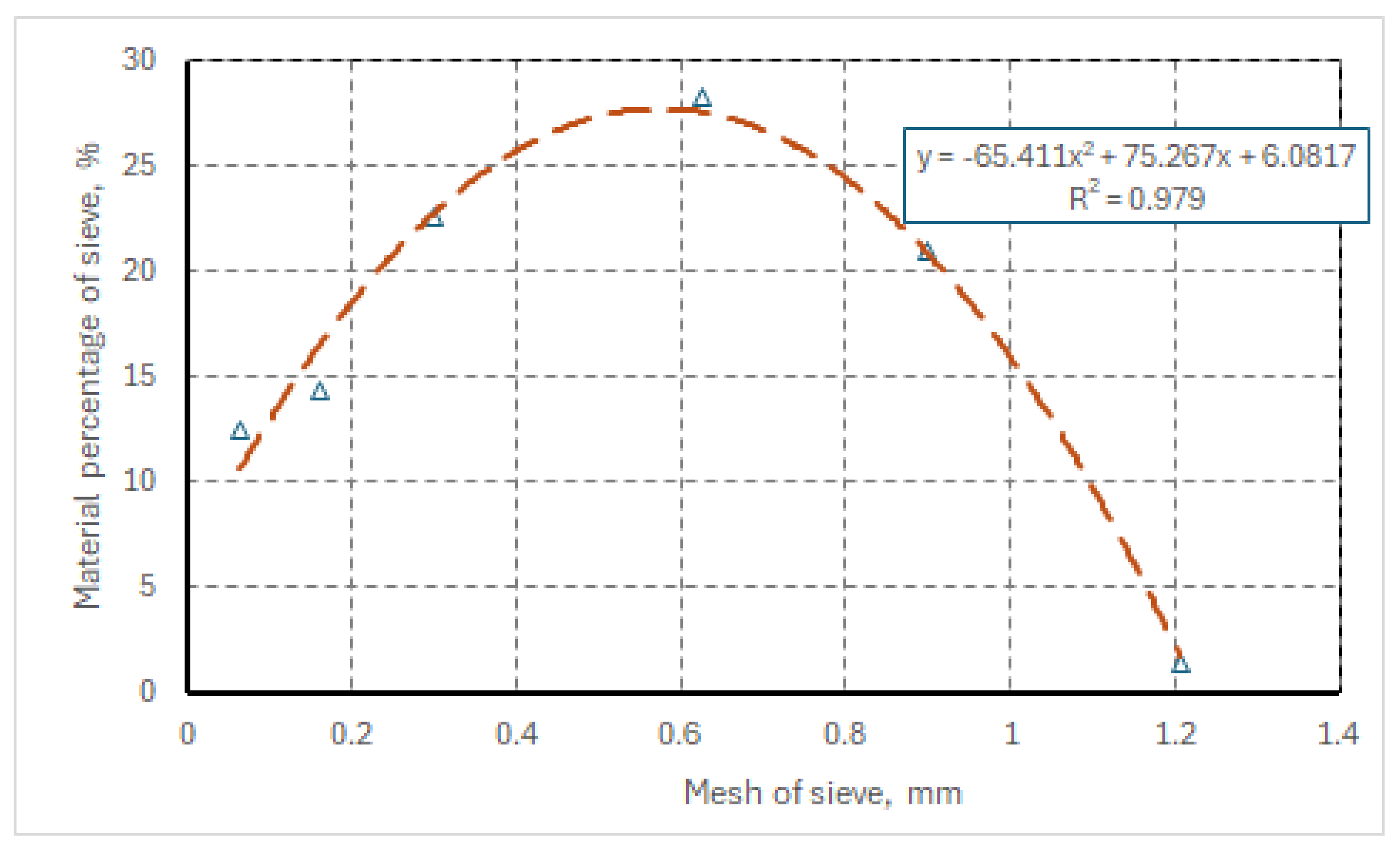

3.1. Particle size distribution of samples

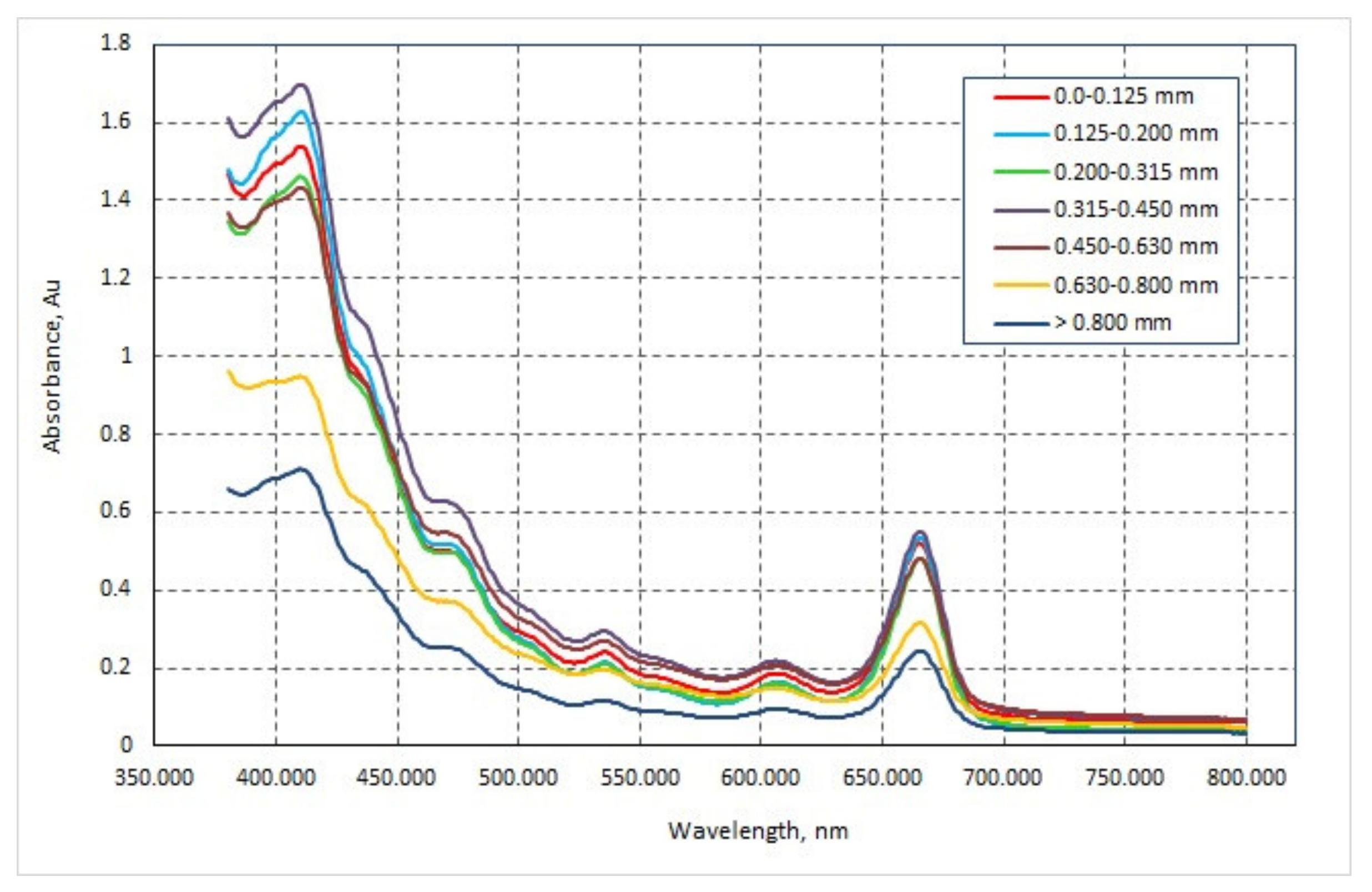

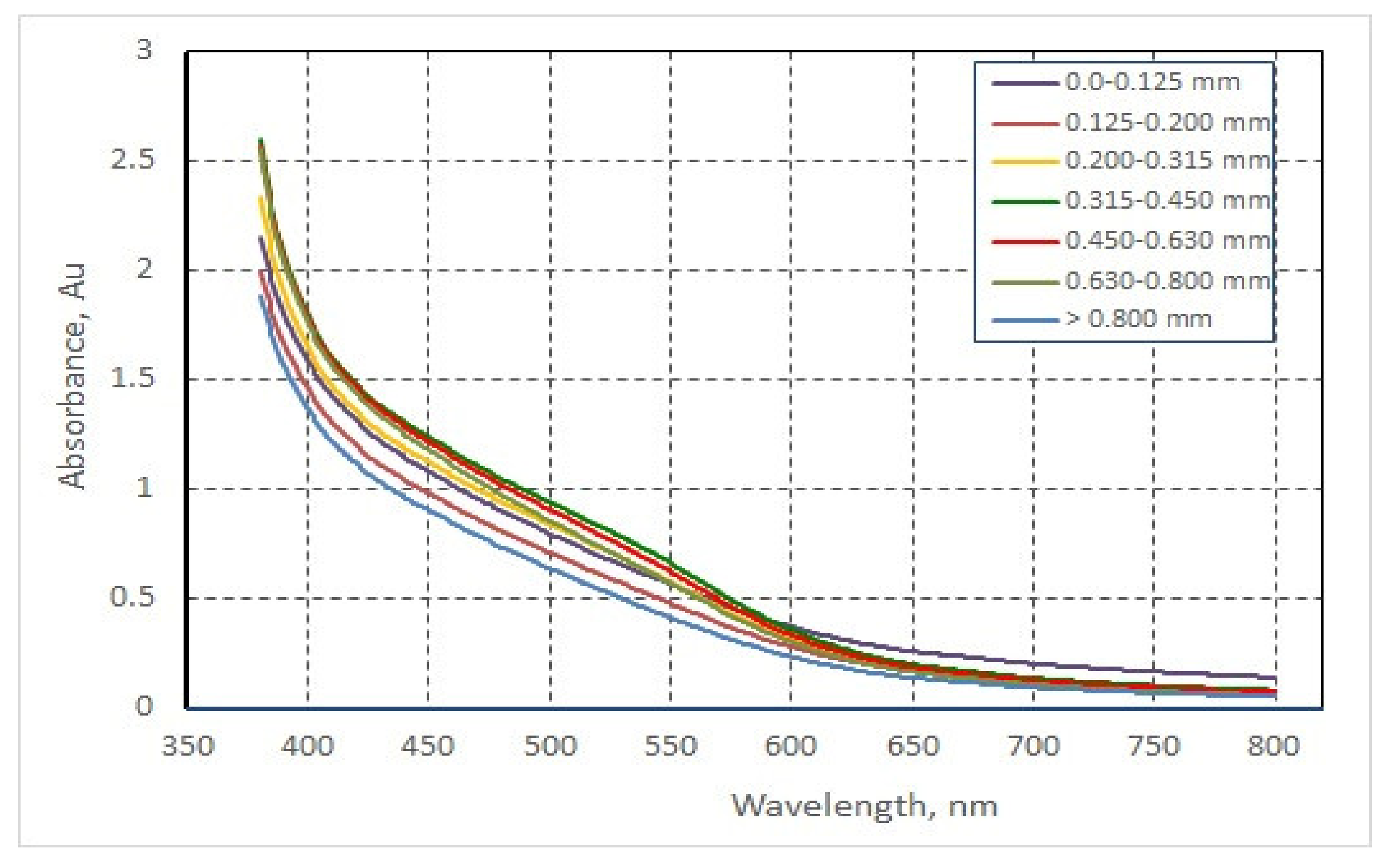

3.2. Analysis of the absorption spectrum of extract

3.3. Moisture content and water activity

3.4. Hydration properties

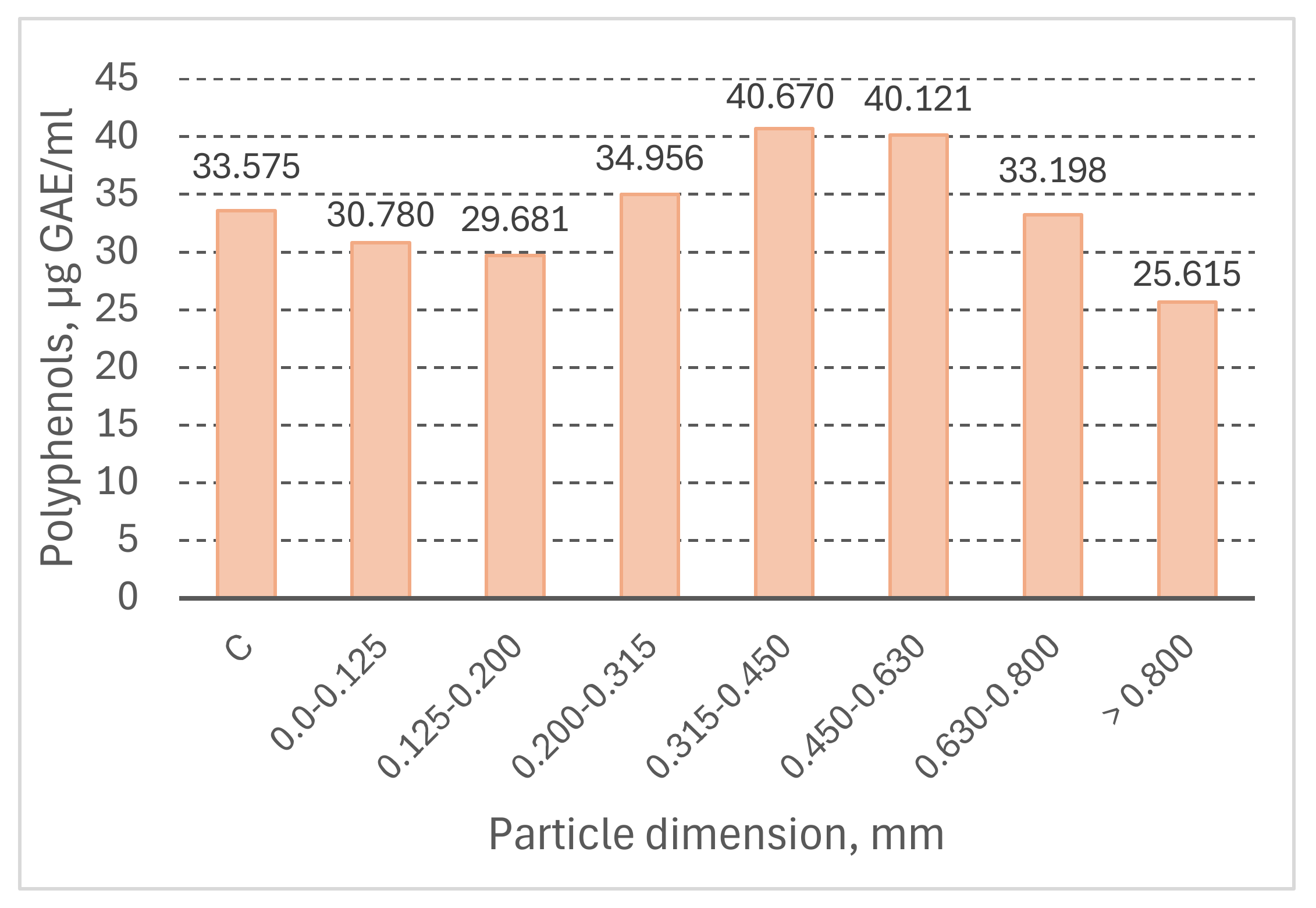

3.5. Total phenolic content

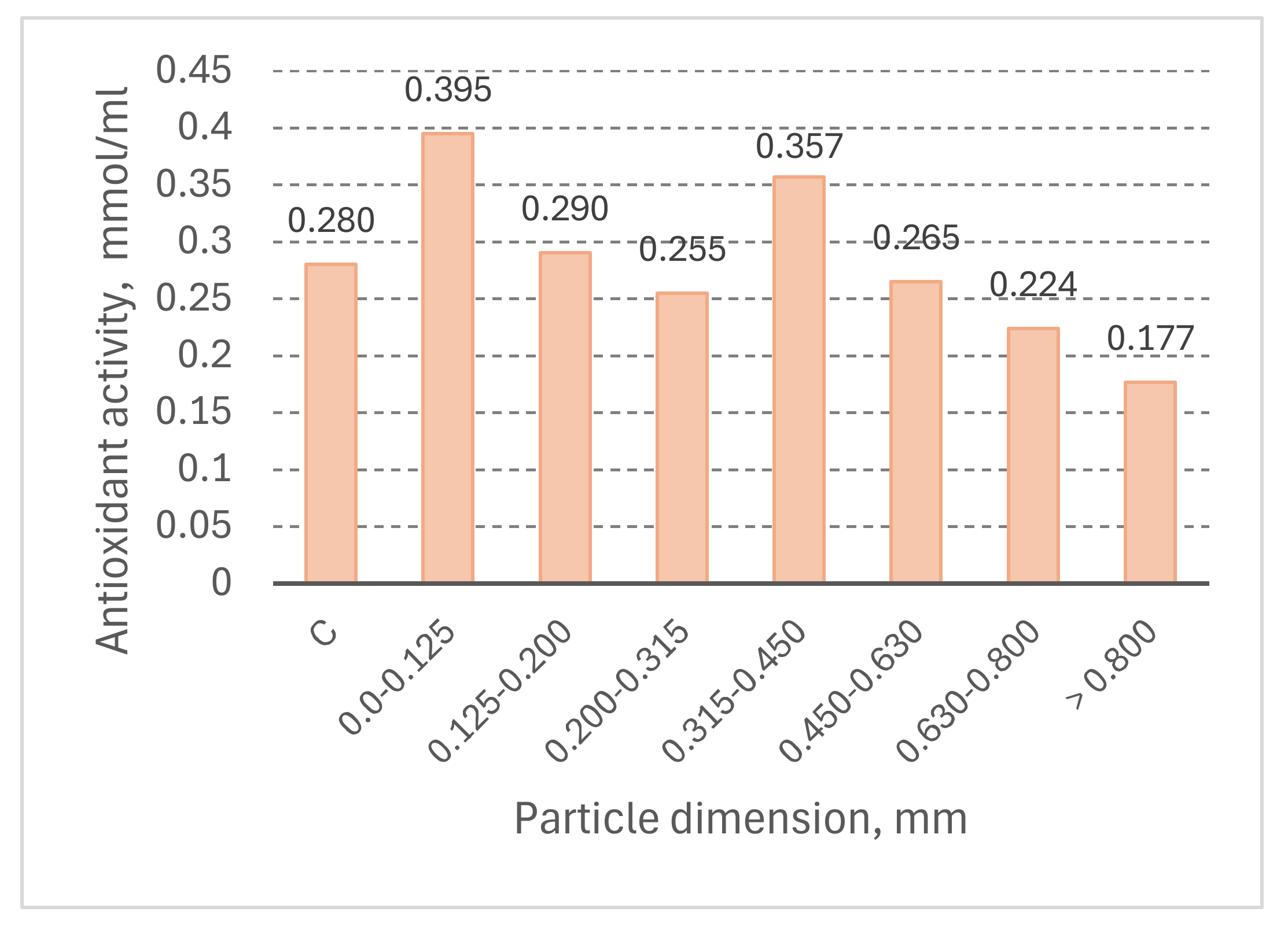

3.6. Antioxidant activity

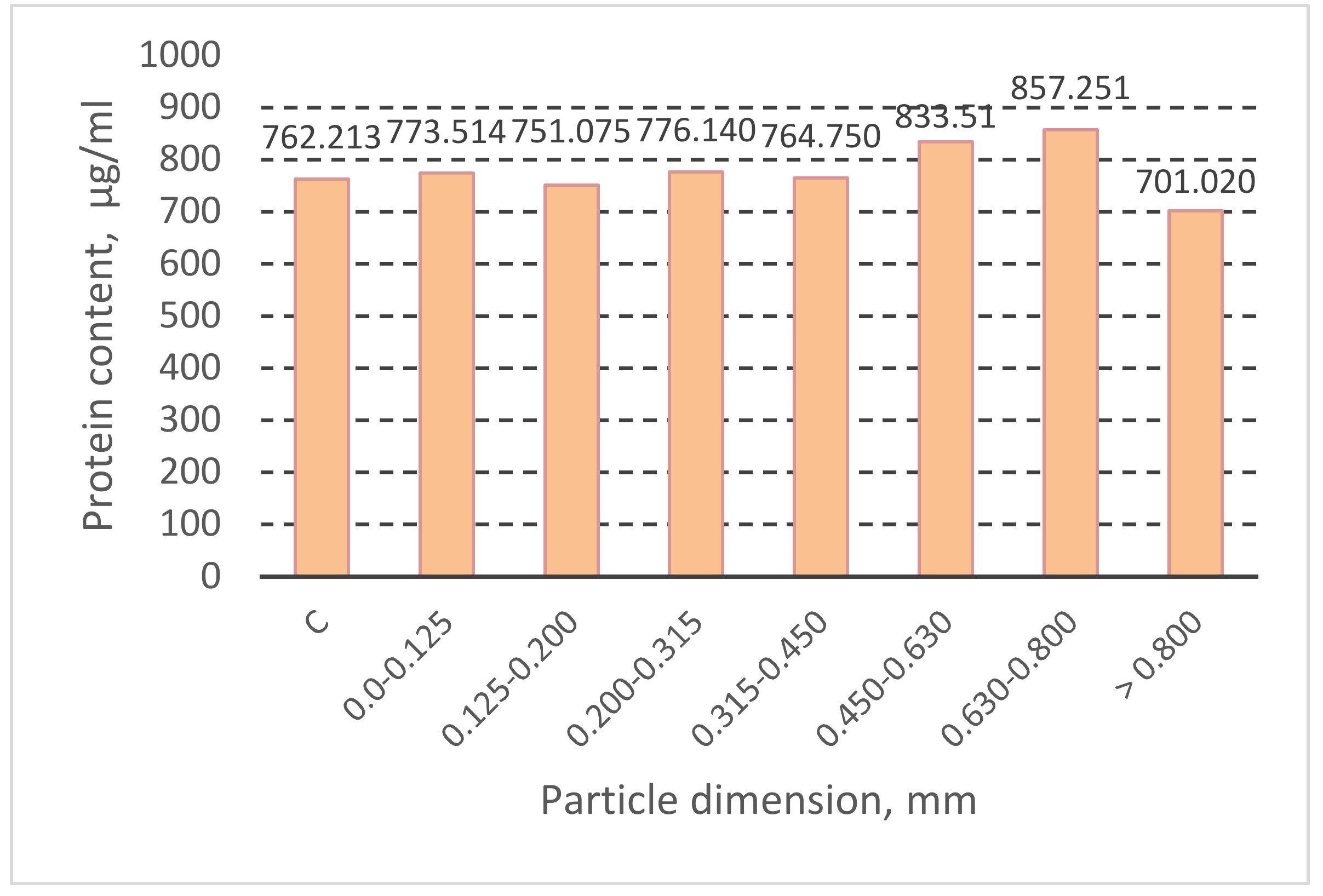

3.7. Proteins

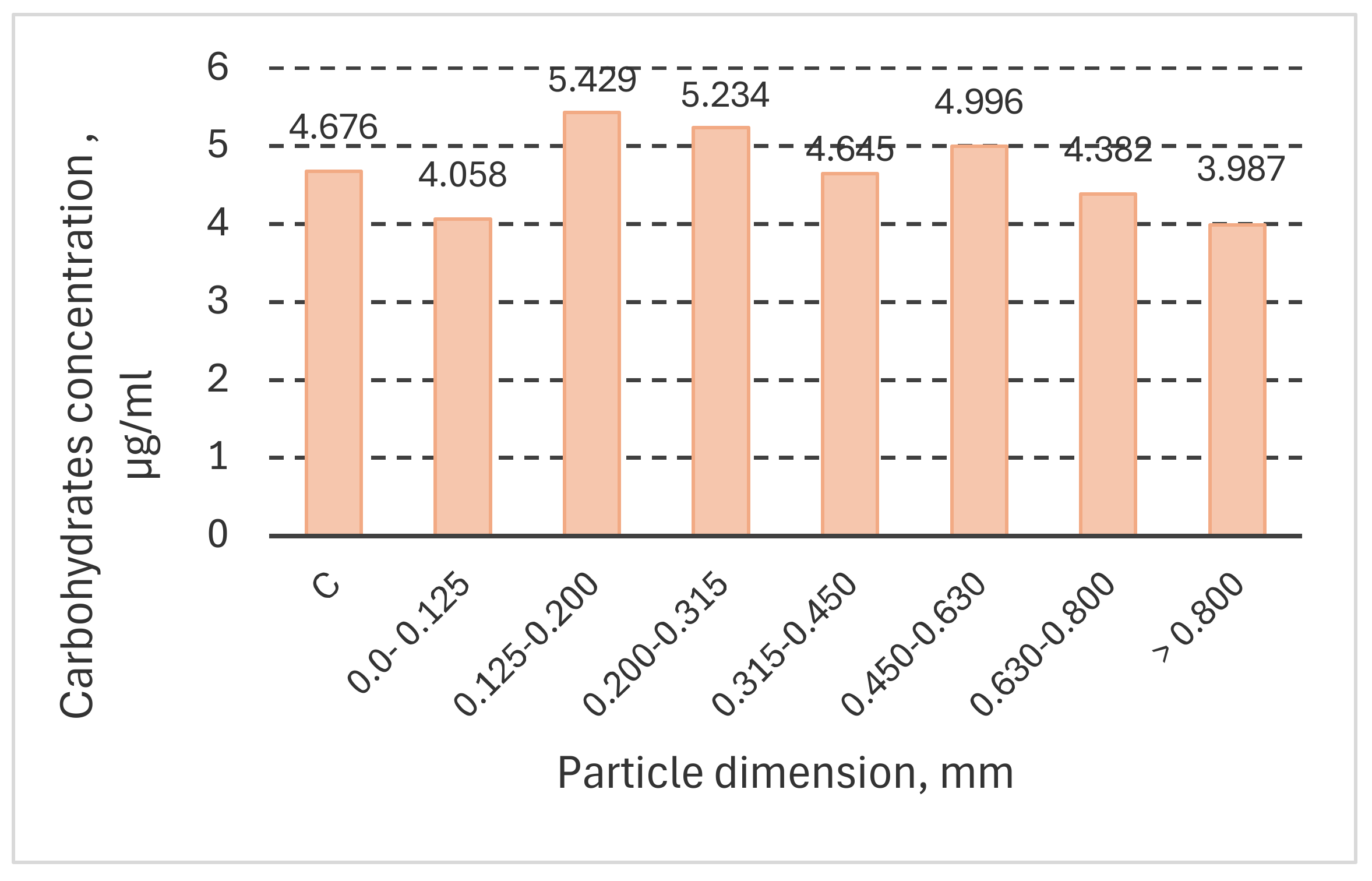

3.8. Carbohydrates

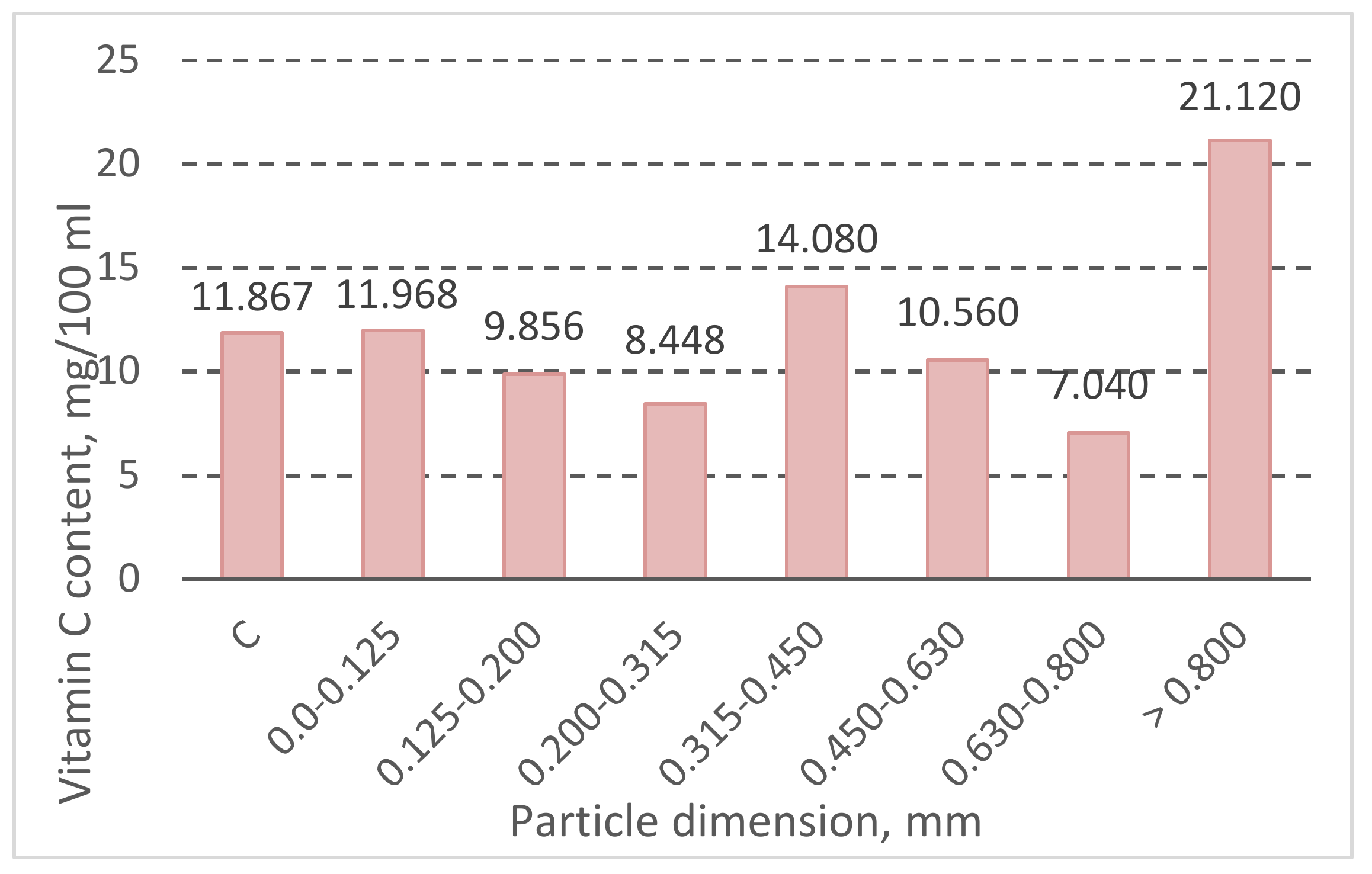

3.9. Vitamin C

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Magiera, A., Czerwińska, M.E., Owczarek, A., Marchelak, A., Granica, S., Olszewska, M. A. Polyphenol-enriched extracts of Prunus spinosa fruits: Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in human immune cells ex vivo in relation to phytochemical profile, Molecules, 2022, 27(5), 1691.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Xu, D.P.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S.; Li, H.B. Bioactivities and health benefits of wild fruits, International journal of molecular sciences, 2016, 17(8), 1258.

- Fernández-Ruiz, V.; Morales, P.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, B.M.; Isasa, E.T. Nutrients and bioactive compounds in wild fruits through different continents, Wild plants, mushrooms and nuts: functional food properties and applications, 2016, 263-314.

- Bei, M.F.; Apahidean, A.I., Budau, R.; Rosan, C.A.; Popovici, R.; Memete, A.R., Domocos, D.; Vicas, S.I., An Overview of the Phytochemical Composition of Different Organs of Prunus spinosa L., Their Health Benefits and Application in Food Industry, Horticulturae, 2023, 10(1), 29.

- Kotsou, K.; Stoikou, M.; Athanasiadis, V.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Mantiniotou, M.; Sfougaris, A.I.; Lalas, S.I. Enhancing Antioxidant Properties of Prunus spinosa Fruit Extracts via Extraction Optimization, Horticulturae, 2023, 9(8), 942.

- Popovic, B.M.; Blagojević, B.; Pavlović, R.Z., Micić, N.; Bijelić, S.; Bogdanović, B.; Misan A.; Duarte C.M.M.; Serra, A.T. Comparison between polyphenol profile and bioactive response in blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) genotypes from north Serbia-from raw data to PCA analysis, Food chemistry, 2020, 302, 125373.

- Babalau-Fuss, V.; Becze, A.; Roman, M.; Moldovan, A.; Cadar, O.; Tofana, M. Chemical and technological properties of blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) and rose hip (Rosa canina) fruits grown wild in Cluj-Napoca area, Agricultura, 2020, Vol. 113, No. 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Nistor, O.V.; Milea, S.A.; Pacularu-Burada, B.; Andronoiu, D.G.; Rapeanu, G.; Stanciuc, N. Technologically Driven Approaches for the Integrative Use of Wild Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) Fruits in Foods and Nutraceuticals, Antioxidants, 2023, 12(8), 1637.

- Popescu, I.; Caudullo, G. Prunus spinosa in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats, European Atlas of Forest Tree Species, Prunus Spinosa, 2016, Publ. Off. EU, Luxembourg, pp. e018f4e+.

- Mitroi, C.L.; Gherman, A.; Gociu, M.; Bujanca, G.; Cocan, E.N.; Radulescu, L.; Megyesi, C.I.; Velciov, A. The antioxidant activity of blackthorn fruits (Prunus spinosa L.) review, Journal of Agroalimentary Processes and Technologies, 2022, 28(3), 288-291.

- Veličković, I.; Žižak, Ž.; Rajčević, N.; Ivanov, M.; Soković, M.; Marin, P.D.; Grujić, S. Prunus spinosa L. leaf extracts: Polyphenol profile and bioactivities, Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 2021, 49(1), 12137-12137.

- Capek, P.; Košťálová, Z. Isolation, chemical characterization and antioxidant activity of Prunus spinosa L. fruit phenolic polysaccharide-proteins, Carbohydrate Research, 2022, 515, 108547.

- Gunes, R. A Study on Quality Properties of Blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) Fruit Powder Obtained by Different Drying Treatments. In BIO Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences, 2024, Vol. 85, p. 01011.

- Negrean, O.R.; Farcas, A.C.; Pop, O.L.; Socaci; S. A. Blackthorn-A Valuable Source of Phenolic Antioxidants with Potential Health Benefits. Molecules, 2023, 28(8), 3456.

- Magiera, A.; Kołodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Skrobacz, K.; Czerwińska, M.E.; Rutkowska, M.; Prokop, A.; Michel, P.; Olszewska, M.A. Valorisation of the Inhibitory Potential of Fresh and Dried Fruit Extracts of Prunus spinosa L. towards Carbohydrate Hydrolysing Enzymes, Protein Glycation, Multiple Oxidants and Oxidative Stress-Induced Changes in Human Plasma Constituents, Pharmaceuticals, 2022, 15(10), 1300.

- Balta, I.; Sevastre, B.; Miresan, V.; Taulescu, M.; Raducu, C.; Longodor, A.L.; Maris, C.S.; Coroian, A. Protective effect of blackthorn fruits (Prunus spinosa) against tartrazine toxicity development in albino Wistar rats, BMC Chemistry, 2019, 13, Article ID 104.

- Pinacho, R.; Cavero, R.Y.; Astiasarán, I.; Ansorena, D.; Calvo, M.I. Phenolic compounds of blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) and influence of in vitro digestion on their antioxidant capacity. Journal of Functional Foods, 2015, 19, 49-62.

- Sabatini, L.; Fraternale, D.; Di Giacomo, B.; Mari, M.; Albertini, M.C.; Gordillo, B.; Colomba, M. Chemical composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity of Prunus spinosa L. fruit ethanol extract. fruit ethanol extract. J. Funct. Foods. 2020, 67, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchelak, A.; Owczarek, A.; Matczak, M.; Pawlak, A.; Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Nowak, P.,& Olszewska, M. A. Bioactivity potential of Prunus spinosa L. flower extracts: Phytochemical profiling, cellular safety, pro-inflammatory enzymes inhibition and protective effects against oxidative stress in vitro. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2017, 8, 680.

- Nguyen, T.L.; Ora, A.; Häkkinen, S.T.; Ritala, A.; Räisänen, R.; Kallioinen-Mänttäri, M.; Melin, K. Innovative extraction technologies of bioactive compounds from plant by-products for textile colorants and antimicrobial agents. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery. 2023, 1-30.

- Becker, L.; Zaiter, A.; Petit, J.; Zimmer, D.; Karam, M.C.; Baudelaire, E.; Dicko, A. Improvement of antioxidant activity and polyphenol content of Hypericum perforatum and Achillea millefolium powders using successive grinding and sieving. Industrial Crops and Products. 2016, 87, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deli, M.; Baudelaire, E. D.; Nguimbou, R. M.; Njintang Yanou; N. & Scher, J. Micronutrients and in vivo antioxidant properties of powder fractions and ethanolic extract of Dichrostachys glomerata Forssk. fruits. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8(7), 3287-3297.

- Zaiter, A.; Becker, L.; Petit, J.; Zimmer, D.; Karam, M. C., Baudelaire, É.; & Dicko, A. Antioxidant and antiacetylcholinesterase activities of different granulometric classes of Salix alba (L.) bark powders. Powder Technology. 2016, 301, 649–656.

- Becker, L.; Zaiter, A. & Petit, J. How do grinding and sieving impact on physicochemical properties, polyphenol content, and antioxidant activity of Hieracium pilosella L. powders? J Funct Foods. 2017, 35: 666–672.

- Alsaud, N. & Farid, M. Insight into the influence of grinding on the extraction efficiency of selected bioactive compounds from various plant leaves. Applied Sciences. 2020, 10(18), 6362. [Google Scholar]

- Miganeh Waiss, I.; Kimbonguila, A.; Mohamed Abdoul-Latif, F.; Nkeletela, L.B.; Scher, J.; Petit, J. Total phenolic content, antioxidant activity, shelf-life and reconstitutability of okra seeds powder: influence of milling and sieving processes. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 2021, 56(10), 5139-5149.

- Duguma, H. T.; Zhang, L.; Ofoedu, C. E.; Chacha, J. S. & Agunbiade, A. O. Potentials of superfine grinding in quality modification of food powders. CyTA-Journal of Food. 2023, 21(1), 530-541.

- Deli, M.; Ndjantou, E. B.; Ngatchic Metsagang, J. T.; Petit, J.; Njintang Yanou, N. & Scher, J. Successive grinding and sieving as a new tool to fractionate polyphenols and antioxidants of plants powders: Application to Boscia senegalensis seeds, Dichrostachys glomerata fruits, and Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx powders. Food Science & Nutrition. 2019, 7(5), 1795-1806.

- Koraqi, H.; Aydar, A.Y.; Pandiselvam, R.; Qazimi, B.; Khalid, W.; Petkoska, A.T.; Rustagi, S. Optimization of extraction condition to improve blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) polyphenols, anthocyanins and antioxidant activity by natural deep eutectic solvent (NADES) using the simplex lattice mixture design method. Microchem. J. 2024, 110497.

- Damar, I.; Yilmaz, E. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds in blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.): characterization, antioxidant activity and optimization by response surface methodologyJ. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17(2), 1467-1479.

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, B.M.; De Ancos, B.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Fernández-Ruiz, V.; de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M.; Cámara, M.; Tardío, J. Wild blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) and hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna Jacq.) fruits as valuable sources of antioxidants. Fruits. 2014, 69(1), 61-73.

- Benković, M.; Belščak-Cvitanović, A.; Bauman, I.; Komes, D.; Srečec, S. Flow properties and chemical composition of carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) flours as related to particle size and seed presence. Int. Food Res. 2017, 100, 211-218.

- Ahmed, J.; Taher, A.; Mulla, M.Z.; Al-Hazza, A.; Luciano, G. Effect of sieve particle size on functional, thermal, rheological and pasting properties of Indian and Turkish lentil flour. J. Food Eng. 2016, 186, 34-41.

- Bala, M.; Handa, S.; Mridula, D. & Singh, R. K. Physicochemical, functional and rheological properties of grass pea (Lathyrus sativus L.) flour as influenced by particle size. Heliyon. 2020, 6(11).

- Ahmed, J.; Thomas, L. & Arfat, Y. A. Functional, rheological, microstructural and antioxidant properties of quinoa flour in dispersions as influenced by particle size. Int. Food Res. 2019, 116, 302-311.

- Singleton, V. L. & Rossi, J. A. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16(3), 144-158.

- Baliyan, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, R.P. & Chang, C. M. Determination of antioxidants by DPPH radical scavenging activity and quantitative phytochemical analysis of Ficus religiosa. Molecules. 2022, 27(4), 1326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Voicu, Gh; Stoica, D.; Ungureanu, N. Influence of oscillation frequency of a sieve on the screening process for a conical sieve with oscillatory circular motion. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology B (ISSN 2161-6264). 2011, vol. 1, no 8B, p. 1224-1231.

- Li, Z.; Tong, X. A study of particles penetration in sieving process on a linear vibration screen. Int. j. coal sci. technol. 2015, 2, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadree, J.; Shahidi, F.; Mohebbi, M. & Abbaspour, M. Evaluation of effects of spray drying conditions on physicochemical properties of pomegranate juice powder enriched with pomegranate peel phenolic compounds: modeling and optimization by RSM. Foods. 2023, 12(10), 2066.

- Deli, M.; Petit, J.; Nguimbou, R.M.; Beaudelaire Djantou, E.; Njintang Yanou, N.; Scher, J. Effect of sieved fractionation on the physical, flow and hydration properties of Boscia senegalensis Lam., Dichostachys glomerata Forssk. and Hibiscus sabdariffa L. powders. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 1375–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhillon, B.; Choudhary, G., & Sodhi, N. S. A study on physicochemical, antioxidant and microbial properties of germinated wheat flour and its utilization in breads. J. Food Sci. 2020, 57, 2800-2808.

- Chen, X. D. & Özkan, N. Stickiness, functionality, and microstructure of food powders. Drying Technology. 2007, 25(6), 959-969.

- Mueed, A.; Shibli, S.; Al-Quwaie, D.A.; Ashkan, M.F.; Alharbi, M.; Alanazi, H.; El-Saadony, M.T. Extraction, characterization of polyphenols from certain medicinal plants and evaluation of their antioxidant, antitumor, antidiabetic, antimicrobial properties, and potential use in human nutrition. Front. nutr. 2023, 10, 1125106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mieszczakowska-Frąc, M.; Celejewska, K.; Płocharski, W. Impact of innovative technologies on the content of vitamin C and its bioavailability from processed fruit and vegetable products. Antioxidants. 2021, 10(1), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mesh size of the sieve (mm) | Sieve mass (g) | The sample mass found on the sieve (g) | The mass of the sample taken for analysis (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.000 | 392.2 | 1.4 | 100 |

| 0.800 | 474.8 | 21.0 | |

| 0.630 | 458.6 | 14.7 | |

| 0.450 | 305.9 | 13.6 | |

| 0.315 | 413.9 | 12.5 | |

| 0.200 | 335.3 | 10.1 | |

| 0.125 | 391.9 | 14.3 | |

| 0 | 342.5 | 12.4 |

| Mesh size of the sieveli (mm) | The average particle size of fraction di (mm) | The percentage of material with a size between dimensions li and li+1 of the adjacent sieves ai (mm) | The percentage of material smaller than the size of the sieve mesh Ti (%) | The percentage of material larger than the size of the sieve mesh Ri (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.063 | 12.40 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| 0.125 | 0.163 | 14.30 | 12.40 | 87.60 |

| 0.200 | 0.258 | 10.10 | 26.70 | 73.30 |

| 0.315 | 0.383 | 12.50 | 36.80 | 63.20 |

| 0.450 | 0.540 | 13.60 | 49.30 | 50.70 |

| 0.630 | 0.715 | 14.70 | 62.90 | 37.10 |

| 0.800 | 0.900 | 21.00 | 76.20 | 21.00 |

| 1.000 | 1.207* | 1.40 | 77.60 | 22.40 |

| Mesh size of the sieve li (mm) |

Mean of intervals, (mm) | Moisture content (%) | Water activity (-) |

Water absorption capacity, WAC (g/g) |

Water solubility index, WSI (g/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Un-sieved sample | - | 4.52 | 0.241 | 4.905 | 32.672 |

| 0 | 0.063 | 3.31 | 0.232 | 5.883 | 41.284 |

| 0.125 | 0.163 | 3.79 | 0.234 | 5.688 | 40.676 |

| 0.200 | 0.258 | 4.34 | 0.237 | 3.892 | 42.272 |

| 0.315 | 0.383 | 4.71 | 0.242 | 3.958 | 37.920 |

| 0.450 | 0.540 | 5.10 | 0.243 | 3.868 | 35.544 |

| 0.630 | 0.715 | 5.11 | 0.244 | 3.847 | 38.912 |

| 0.800 | 1.131 | 5.61 | 0.250 | 3.837 | 36.828 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).