1. Introduction

Barniz de Pasto is an artistic technique of pre-Hispanic origin, unique in the world, which involves the collection of

mopa-mopa from shrubs in the rural area of Mocoa in the Andean-Amazonian piedmont of Putumayo. It is then transformed into thin coloured sheets that are applied to wood – this technique is currently only practiced in the city of Pasto, Nariño, in the southwest region of the Colombian Andes. However, as is the case in several other crafts worldwide, research on

Barniz continues to be focused on technique and objects [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. There have also been publications about

mopa-mopa in Putumayo that focus on its taxonomy, the main one being by Luís Eduardo Mora Osejo [

16], who classified the shrub from which

mopa mopa is picked as

Elaeagia pastoensis mora.

3 Others relate to the history [

17], location, physico-chemical characteristics, cultivation, and innovation for processing, while warning of its imminent risk of disappearing.

Most of the publications correspond to chronicles, articles, books, user manuals, images and videos in which the harvesters or artisans are only present silently in the background. With the exception of the 2019

Expediente y Plan Especial de Salvaguardia PES (Dossier and Special Safeguarding Plan) [

18], texts and audiovisuals found in various physical and virtual repositories have in common that the wood, cabinetmakers, turners, carvers and harvesters are kept hidden behind the sheets of

Barniz. In the 2019 PES, they were taken into account and named by some of the masters in the marketing of their works, as the Home-workshop of the Granja family has been doing for a couple of years.

4

In short, the history of decoration with Barniz has been looked at through analyses that focus on a fascination with or seduction by works of pre-Hispanic or colonial origin found in private collections or in the world’s most prestigious museums, studies that includes chemical, microscopic, conservation and design aspects. This results in the recognition of a crossbreeding, hybrid amalgamation between Europe, America and Asia which ends in a welcome and grateful syncretism – a sort of co-creation – that produces forgetfulness and silences that erase tensions and agencies between subjects. It almost seems that the objects are (self-)created without any relation to places, home-workshops, workshops or mountain jungles, vegetation (mopa-mopa and wood), tools, women and men, circumstances, cosmic forces, etc.

During the process of patrimonialización of the Barniz de Pasto mopa-mopa, author Giovany Paolo Arteaga Montes was the coordinator for the team of the Fundación Mundo Espiral5 that developed the UNESCO applications (see below) through research and the creation of written, visual and audiovisual discourses, among other activities and products. Ruth Flórez Rodríguez from the Dirección de Patrimonio y Memoria del Ministerio de las Culturas (the Colombian Directorate of Heritage and Memory of the Ministry of Culture), and María Mercedes Figueroa Fernández, as Director of Mundo Espiral and, later, as an official of the Governorate of Nariño, also participated in this process. Between 2013 and 2020, with 45 artisans from the Department of Nariño and 10 mopa-mopa harvesters in Putumayo, the team achieved the recognition of their knowledge and techniques of pre-Hispanic origin, unique in the world, as Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) at the departmental (2014), national (2019) and global levels (2020). Therefore, on December 15, 2020, Barniz de Pasto mopa-mopa was included in UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, in view of their imminent risk of disappearing.

The interesting thing about these processes is that they gradually led us to realise that we were engaging in ethnographies that summarised journeys, crusades or missions from the centres of learning or power to the ‘ends of the earth and time’, now known as ‘territories’. We were the protagonists and the authority that planned, observed, controlled and were ‘immersed’ in this always extraneous reality, in order to develop an idea that created a contrast between a past, a present, a future, and fragmented networks of others, which were then described, valued and influenced by our voice as travelers [

19] (pp. 23-26).

Thus, we decided to turn around and carry out ethnographies that would take the form of spatial and experiential journeys, insofar as they involved moving and walking in company, talking, being attentive, allowing ourselves to be taught and live with the people who participate in the production of Barniz de Pasto (harvesters and artisans), in the places where daily life takes place: mountain jungle of the Andean-Amazonian piedmont of Putumayo, carpenters’ workshops and Home-workshops of the craftspeople in the Nariño Andes, specifically in Pasto.

These journeys were also lived experiences. They had their own rhythms and timeframes that left traces or scars from the shared moments, which pierced our bodies and souls with their energy, taking place from within to without and the other way round for those who experienced them, because we walked together, gave our all without holding anything back, like a large family. Because everything around us passed through us (sometimes unnoticed) and was passed through by us in turn, without a clear destination, without a clear horizon, as it is in life.

In this way, we carried out ethnographies at ground level and with dirty hands, as proposed by the anthropologist Luís Alberto Suárez Guava [

20], where past(s), present(s) and future(s) merged through the multiple relationships between humans and non-humans, subjects-objects, which allowed us to make people and scenarios visible in order to understand the

Barniz de Pasto mopa-mopa from another perspective, which we have called: ‘behind the objects’. A similar concept was expressed by conservator Dana Melchar, scientist Lucia Burgio and curator Nick Humphrey at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, with a

Barniz cabinet decorated around 1650 that revealed a skeleton of death hidden beneath its ornamentation, imperceptible to the naked eye [

21].

That is why, with this paper, we want to reveal and relate what has so far gone unnoticed, through ethnographies of the production process of the objects made with

Barniz de Pasto. The aim is to reassemble the relationships between humans (harvesters, woodworkers and master artisans) and non-humans (raw materials, tools, places, works, etc.) as expressed by Bruno Latour [

22], fragmented by a fascination with objects, as happens in most popular arts worldwide.

The text is organised in the form of ethnographic overviews:

The Home-workshops of the masters of Barniz de Pasto;

The workshops of the woodworkers;

The montañas-selvas and the mopa-mopa harvesters;

The works (objects, products, merchandise).

These will be assessed in their current dynamics in order to understand what is happening with them, the people involved - together with those who are becoming involved - and the changes that are being implemented in the technique. Unlike a conventional academic paper, we will not end with closed and immutable conclusions. Rather, the reader will find in each of the paragraphs reflections from ten years of our accompanying artisans and harvesters, always open for discussion.

2. Ethnographic Overview 1: the Home-Workshop of the Masters of Barniz de Pasto

It is a September morning in 2013, accompanied by an immaculate blue sky and a radiant sun that rises in front of the Galeras volcano while it enlivens the mountain walls that surround the Atriz Valley, the seat of the city of Pasto and its inhabitants (

Figure 1). A bright morning that anyone would say is hot, but which can be summarised as warmly cold due to the roar of the icy wind, just a typical Andean autumn morning. We arrived at the home-workshop of the Granja Masters located in Tamasagra - a neighbourhood that commemorates a local

cacique - a neighbourhood somewhat distant from the city centre and which has its difficulties related to violence and crime. After wandering through its pedestrianised streets for a few minutes, we rang a bell at a modest house with white railings and a light green façade.

The door was opened to us by the young artisan Óscar Granja, who greeted us with a big hug, while his elderly father, Gilberto Granja, examined us in detail before stretching out his hand to shake our hands. The scene that met us comprised: a dog by the name of Oso, two ceremonial chairs around a small table on which a portable stove was placed, heating a pot containing mopa-mopa buds, which exhaled their welcome steam. An old sound system that transmitted the news in AM (Amplitude Modulation) under the exclusive authority of master Gilberto, a kind of hammer with incisions called ‘buzarda’, ready to macerate the buds on a trunk with a rectangular plate on top, a wide piece of sacking ready to rest on the legs, in order to facilitate the cleaning of the raw material through the friction of the hands, the use of the nails, the cooking and the shaking. Everything rested close to the light radiating from the window in the room, behind a white curtain that served as a lamp shade.

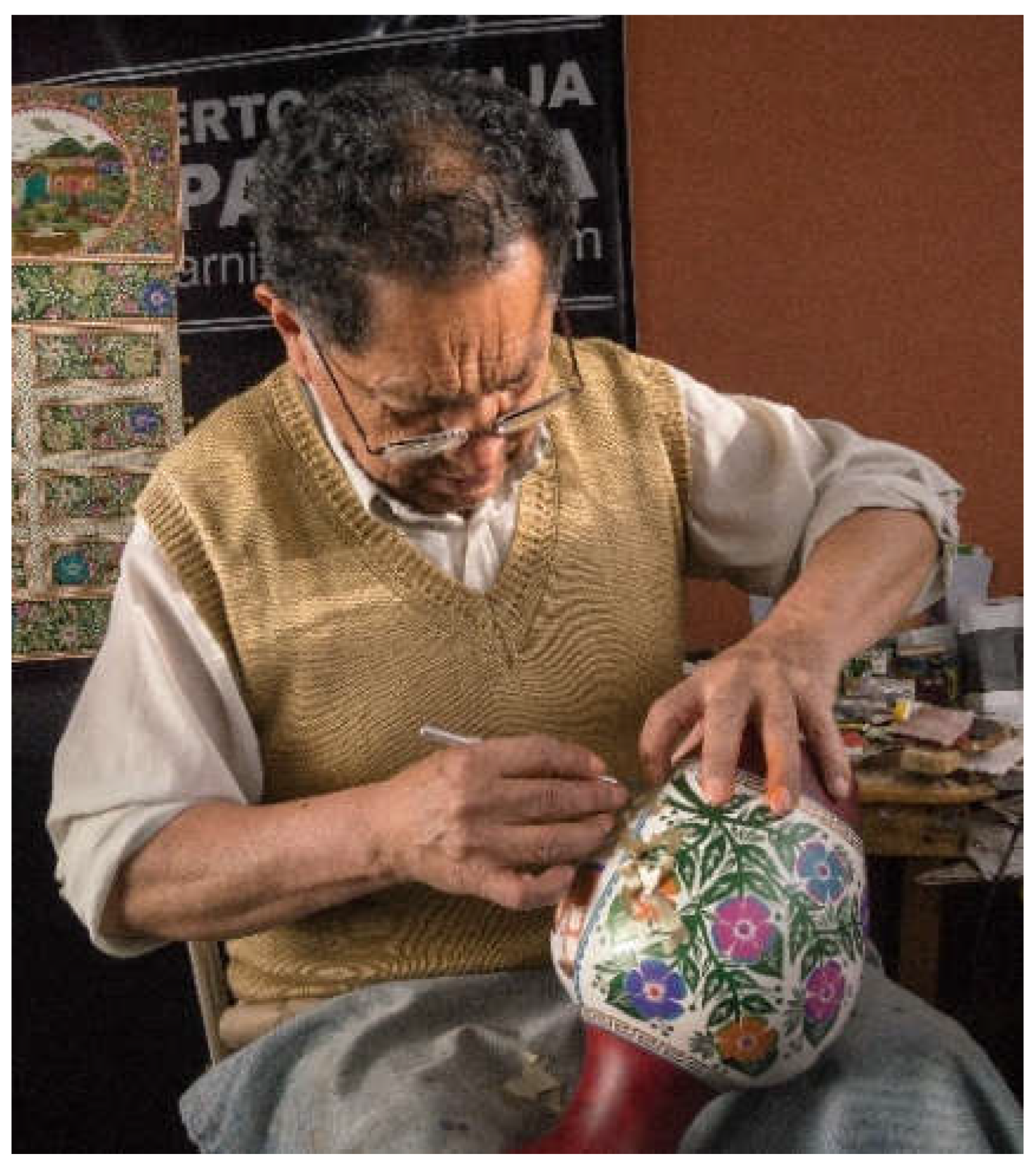

In the background, several wooden objects on two shelves made of the same material, arranged by size and shape, patiently awaiting their turn to be decorated. The hands of the masters are coloured orange, red and blue from the ‘El indio’ anilines used to give the

Barniz sheets their hues. These are delicately stretched between the fingers and mouths of two working partners looking at each other intensely, until the desired thickness is achieved. An oblique body posture, a mark of their work in which they use a ‘magic knife’ adapted by each of them from the fragment of a saw. The surgical scalpel is the protagonist in the decoration of objects as it is an extension of their body and mind, whether it is a craftsman or surgeon who seeks to do his work well (

Figure 2). On their legs they also have a blanket or coverlet and on top of it the object on which they will leave the trace of their skin, to the extent that the pressure of their fingers, hands and forearms is needed to adhere the

mopa-mopa sheets to the wood. There is a close connection between nature, body, soul and tools that denotes concentration, coordination, skill and cooperation as Richard Sennett would put it [

23] (pp. 31-263).

Once we came back to ourselves, after passing through that magical place, we talked about cultural heritage, thanks to the invitation made to us at the time by the conservator and now councillor of Pasto Álvaro José Gomezjurado Garzón. From that moment on, we started to walk alongside Oscar Granja (one of the few workers or officials who recognise their collaborators and the small number of family apprentices) to look for the 5 master craftswomen and 31 master craftsmen who dedicate themselves to this artisan practice in the city of Pasto (

Figure 3 to

Figure 6). It took us 12 months to carry out a census, a part of the process of

patrimonialización that lasted six more years.

Figure 3.

Barniz de Pasto Home-workshop, Maestros Jhonatan and José María Castrillón stretching a sheet of mopa-mopa. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2023.

Figure 3.

Barniz de Pasto Home-workshop, Maestros Jhonatan and José María Castrillón stretching a sheet of mopa-mopa. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2023.

Figure 4.

Barniz de Pasto Home-workshop, Maestro Alfredo Zambrano and family. Photography by Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2023.

Figure 4.

Barniz de Pasto Home-workshop, Maestro Alfredo Zambrano and family. Photography by Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2023.

Figure 5.

Barniz de Pasto Home-workshop, Maestro Óscar Ceballos and his apprentice María Camila Muñoz. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2023.

Figure 5.

Barniz de Pasto Home-workshop, Maestro Óscar Ceballos and his apprentice María Camila Muñoz. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2023.

Figure 6.

Barniz de Pasto Home-workshop, Maestra Mary Ortega, Maestro Mario Narváez and their apprentices. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2023.

Figure 6.

Barniz de Pasto Home-workshop, Maestra Mary Ortega, Maestro Mario Narváez and their apprentices. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2023.

3. Ethnographic Overview 2: the Workshops of the Woodworkers 6

Around October 2019 - six years after the meeting with Óscar and Gilberto - the master artisans told us one of their many ‘secrets’,7 in this case related to the 10 suppliers of wood, which include five wood turners, three cabinetmakers and two carvers. The first are elderly men who have their workshop mainly in the classic Obrero neighbourhood of the city of Pasto and two of them - the youngest - in the municipality of El Peñol, Nariñoawn.

Here, the home-made ‘electric lathe’ is the main tool used to shape round and oval objects such as vases and bonbonnieres with the force of the body that is impressed through gouges, chisels and cutters (

Figure 7). As Efrén Taborda expresses it, these workshops are characterised by their modest size and the absence of apprentices, as it is considered a complex and risky job to teach, because it can cause accidents ranging from small cuts to the amputation of fingers. This is in addition to the practically non-existent work safety conditions, which generate respiratory problems due to the dust by-product from the manufacture of the objects. Apprenticeships could bring more difficulties than benefits.

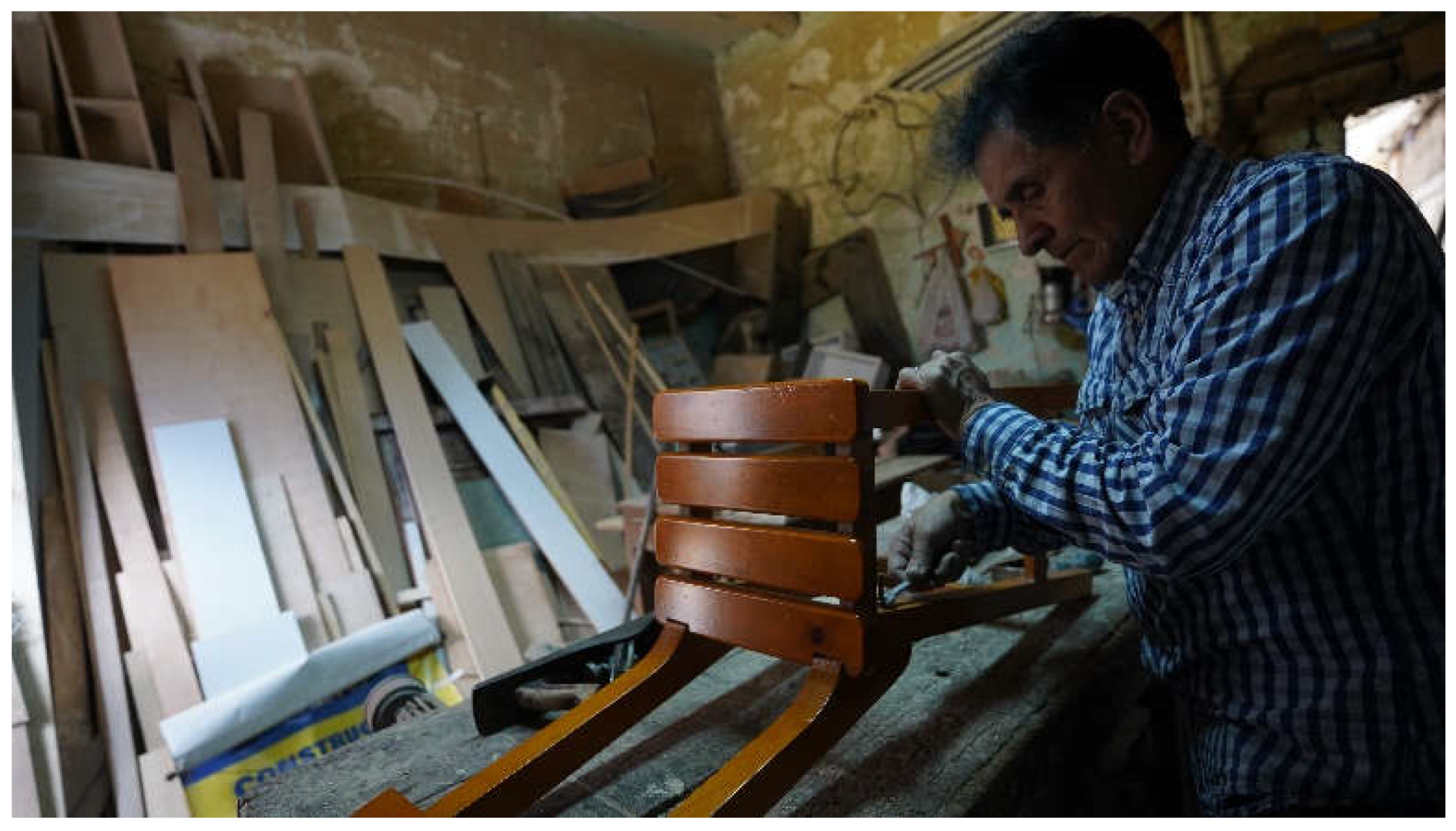

At the same time, in San Felipe, a sector near the Obrero neighbourhood, there is an old one-storey house built with adobe bricks and clay tiles that looks more like an old-fashioned grocer’s shop. Right there, there is a long, thick table decorated with a fine dust that sticks to everything, a floor padded with sawdust on which footprints are left, along with boards of various types of wood resting vertically leaning against the walls waiting to be worked on. Here we spoke with cabinetmaker Ricardo Mauricio Bolaños, who designs, makes and finishes square or rectangular furniture such as desks, chairs, bedroom sets, dining rooms, kitchens, wardrobes,

bargueños and ‘secret boxes’, so called because they have a hidden opening mechanism (

Figure 8).

In the middle of the conversation, Mauricio was emphatic in expressing that the carpenter helps to assemble the product, but does not start or finish it as the cabinetmaker does, using electrical tools to shape the wood, such as the router, gluing machine, drill and auger. In his work, he also needs saws, jigsaw, planers, glue and tape measure, among others. Furthermore, in addition to selling his works to Barniz de Pasto artisans, he uses his knowledge to offer them to multiple clients and, as turners and carvers do, he works to order.

At the end of the same year, we arrived with the audiovisual production team at the La Minga neighbourhood in the south-east of the city of Pasto. This is the place where master Guillermo Cuaces and three other people carve wood (

Figure 9). In this space it was striking to meet the young Elizabeth Rosero Chicaiza who used to be an apprentice and helper, but now is dedicated to other tasks. Here, in the midst of gouges, chisels and crowbars of different sizes, there are unique hammers, sandpaper of different grades, brushes and the force that is impressed on this substrate. These hands amazingly made masks,

ñapangas (peasant woman from Nariño) and animals of various sizes to be decorated.

During the conversation, master Cuaces told us that only some of the carpenters - in his general definition - sell their work directly to the artisans, because there are three agents in Aruba who market the wooden and decorated pieces for sale. They have been taking care of a large part of the production process for several decades, with an excellent profit margin for them - the ‘resellers’ - reflected in dollars, thanks to their sales strategy that concentrates on the cruise ships that arrive at the tourist port in the Caribbean.

4. Ethnographic Overview 3: the Montañas-Selvas and the Mopa-Mopa Harvesters

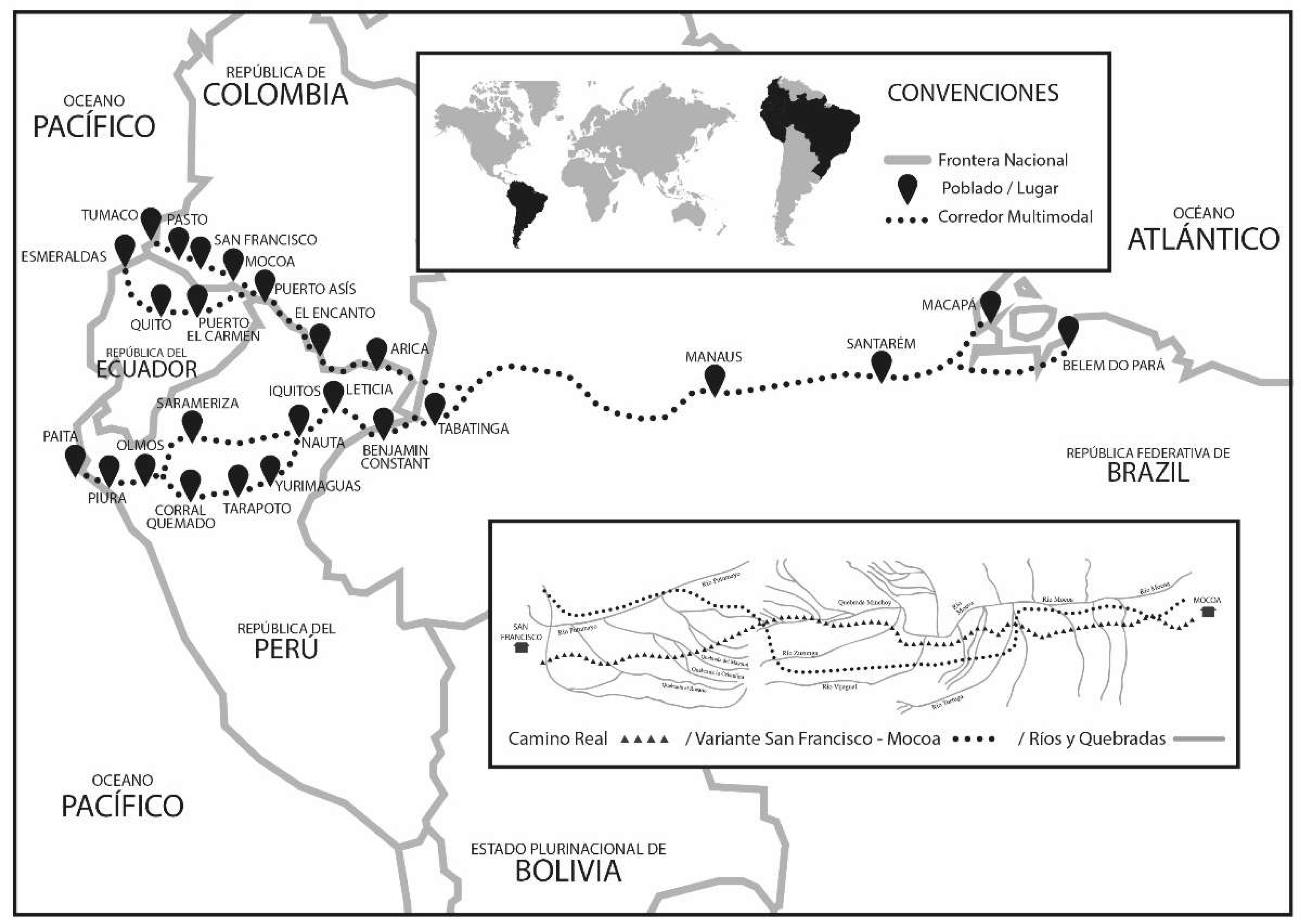

During 2019 we also travelled along the ‘Trampolín de la muerte’ (‘death road’), an unpaved road in the middle of imposing abysses that connects Pasto with Mocoa. This road will be replaced by the construction of the San Francisco – Mocoa road section, part of the Multimodal Corridor Tumaco - Pasto - Puerto Asís - Belem do Pará (

Figure 10), which seeks to promote the Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America (‘Integración de la Infraestructura Regional Suramericana’, or IIRSA). The main objective of the Multimodal Corridor is to promote the development of southern Colombia, northern Ecuador, Peru and Brazil, by strengthening trade and facilitating the connection between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. At the same time, it will extract the riches of the Amazonia, linking the latter to the global economy even more. Under this plan, the section between the municipalities of San Francisco and Mocoa will cross the forest reserve area of the upper basin of the Mocoa River, home to non-human beings, some peasant families and headquarters of mining companies. The few

manchas (‘patches’)

de mopa-mopa that exist in the Andean-Amazonian piedmont are found here in particular (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

Once we crossed the famous ‘Trampolin’ to Mocoa, we visited 10 ‘barniceros’ or ‘cosecheros’, as they call themselves, renamed modernly as

recolectores (harvesters), who obtain the

mopa-mopa from the scarce bushes scattered in areas with specific characteristics of altitude, humidity, sunlight and soil conditions that give life to the ‘

manchas de mopa-mopa’. ‘There where the clouds are’ - as the

barnicero Pedro Pablo Zuin says - only his wife Marciolina Gaviria and their children climb the steep trails (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14); as well as the married couple Evelio Bravo and Isabel Cerón; Mery Cerón and her son Juan Eliceo Gelpud; Jesús Cerón, Armando Becerra; Jorge and Edinson Macías, father and son, respectively.

Campesinos who survive with their families clinging to rubber boots, a machete, a

garabato (a stick that ends in the shape of a hook), a small backpack and a humble hut. It is a family tradition that does not generate economic profit, for which it is always necessary to walk uphill for 5 to 8 hours from 800 metres above sea level to 1600 or 2200 meters to find the buds that will be transformed into

Barniz.

It is necessary to carry more than one arroba (a traditional unit of measurement equivalent to approximately 12 Kg) of food to spend 10 to 15 days in the montañas-selvas, an effort to collect a maximum of 15 kilos of buds and bull horns (because of their shape). There is a commercial relationship in which each kilo is sold directly to the artisans of Pasto for $200,000 COP, equivalent to just over 40 GBP (at the exchange rate of spring 2024). Currently there are two harvesting seasons: March and November. There have been changes due to global warming: these are places where the complex global environmental situations affecting the rainforest have to be overcome: the advance of deforestation, climate change, the presence of crops for illicit use, the violence present in the area, large-scale mining, the scarcity of the Elaeagia Pastoensis bush and its respective pests (cutworm or weevil), along with the expansion of the frontiers of agriculture, livestock production and indigenous reservations. This is compounded by the solitary work that the barniceros do, insofar as they are older adults whom young people do not want to accompany to learn; they consider it arduous and dangerous work, not at all profitable, which is added to the non-existent recognition of the people who carry out this work and the undervaluation of the mopa-mopa.

5. The objects

The decorative technique, and even more so the finished works, is what most attracts the attention of scholars and customers (

Figure 15). Generally, hardly anyone pays attention to the people who create the objects and much less to the sacred places where they collect and transform the raw material. This situation has dogged

Barniz for the duration of its history, and us since 2013. To reverse this, with the team we organised several exhibitions at the local and national level involving the harvesters and artisans. But as is the case in the production of these crafts - and probably in others - the existence of the objects is still the only thing that is almost exclusively recognised, and lately a few men linked to the decoration, thanks to the debate they have created about themselves through the

patrimonialización process. These masters, together with their families, have vehemently fought for these spaces of recognition in the market in order to overshadow their rival colleagues and thus shine within the guild, among the civil servants and institutions. However, the master craftswomen who work with wood and

Barniz in the city of Pasto, as well as those women and men who are dedicated to the harvesting of

mopa-mopa, remain hidden behind the

mopa-mopa sheets in their homes-workshops, workshops,

montañas-selvas with their pros and cons.

As mentioned above, most texts and research projects are dedicated to the analysis, conservation and history of objects decorated with

Barniz, carried out by scientists, curators and conservators [

1,

2,

5,

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] or consist of comparative studies with Japanese lacquer [

6,

7,

8]. Microscopic and spectroscopic analyses have also been carried out on

Barniz objects in various museums around the world, such as the one done in 2015 by Newman et al. on

qeros, pre-Hispanic ceremonial vessels [

10].

In 2018 a

Barniz cabinet from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London was investigated, and calomel, a white pigment containing mercury, was found [

11]; a similar discovery was made in 2020 by Pozzi et al. in a seventeenth-century work [

3]. These were analyses that astonish the small academic world interested in

Barniz de Pasto due to the complexity of the techniques involved. However, it would be equally, if not more, surprising to find today the large quantities of mercury and other chemicals that are permeating soil, streams and rivers in the Amazon, which leave their scars as a result of agriculture and indiscriminate mining extraction by multinational companies from the same countries that cry out for the environment and boast about the status of their ‘development’. States with institutions that in some cases dedicate their efforts to understanding the physico-chemical benefits of the

mopa-mopa, a motivation that Colombia does not yet have.

Changes in design have also been studied, nurtured by practices that were previously called ‘mingas’ (voluntary gathering of people to carry out construction works and repairs or to establish guidelines that benefit the community). The mingas are now viewed as collaborative and co-creation methodologies, innovative processes that end up legitimising the opinion of the professionals. In what is always a hierarchical relationship, the professionals emphasise their own judgement and sense of importance in the elaboration of objects that are fully conceived before they are even started. The novel designs therefore have been projected, oriented and submitted to the pre-approval of experts. The master craftsmen and craftswomen are themselves one more object to decorate, exoticise and a means to give a face to the technique; in order to claim collaboration between artists and artisans, the masters are used in photography or videos, for exhibitions or reports. Having said that, this relationship is mutually beneficial and is used to generate debates and increase recognition that cannot be measured by the same yardstick.

Technology adds to these processes, as the officials of the Secretary of Culture of Pasto said in 2023: ‘to drive the evolution of the technique’ and generate ‘more functional goods that meet the needs of the market and customers, nothing traditional or pre-Columbian’. If so, hopefully the technology comes from a designer, artist or recognised brand, and includes innovation in centrifugal machines and mixers that speed up the process of cleaning the raw material and allow production in large quantities.

At the same time as the announcement of the inclusion of Barniz de Pasto in the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Paris on 15 December 2020, publicity also began to circulate for mopa-mopa decorated bottles of a world-famous brand of liquor, which - according to various sources - fetched hundreds of dollars on the national and international market. However, the artisans were paid COP 70,000, equivalent to about GBP 14, for their efforts. None of them made a profit. However, they were still satisfied because the important thing was recognition, even if only Germán Obando, son of the charismatic master José María Obando (RIP), was given visibility.

This recognition has increased the number of visits by renowned designers and companies to home-workshops, to expand the use of mopa-mopa to different types of decorations, including souvenirs and furniture finishes in houses and flats: doors, countertops and cabinets, etc., which can be decorated and the work charged per square centimetre; and there are even dreams of requesting volumes of thousands of objects and filling shipping containers that circle the seas. These are dreams that could never be achieved, even if the small number of people who dedicate themselves to this work toiled 24 hours a day for the rest of their lives, without forgetting the difficulty in obtaining raw materials.

Driven by the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent supposed need to jumpstart the economies, it is also considered necessary to strengthen commercialisation in the virtual world. This, together with the visualisation of works in 3D, augmented reality and laser cutters to improve the quality of the decoration, will probably turn the ‘traditional’ Barniz towards other dynamics of manufacturing, maquila8 and industry that is now also beginning to be tied to a tourism that does not take into account the local hosts, only the travelers. It is worth noting that, like all seemingly uncertain futures, we cannot predict the positive or negative impacts that such processes may generate. Although the reader can clearly sense which way we believe it is going to go.

‘Performances’ of artisans and crafts manufactured by external professionals, ignoring the intimate, alchemical and profound relationships between subject(s)-object(s) or culture(s)-nature(s) and vice versa, relationships that we have shared for many years and that are constantly transforming us, but that now seem to be guided solely and exclusively by the needs of the cultural industry.

In short, without the scarce mopa-mopa or wood, there will be no harvesters and artisans who work the Barniz, without the Amazon there will be no life. Perhaps, the journeys we propose are an opportunity to let ourselves be transfixed by every word, feeling or sensation in order to share what happens in these magical places: the homes-workshops of the Barniz, the workshops of the woodworkers and the montañas-selvas of mopa-mopa, spaces in which apparently only objects, techniques, tools and raw materials existed in the absence of humans. As Richard Senneth proposes [Sennet]: ‘“Craftsmanship” designates an enduring and basic human impulse, the desire to perform a task well’. For this reason, we also want to do our task in the best way: as historians, that we describe together with harvesters and craftsmen how the subject-object relationship manifests itself; as anthropologists, that we narrate what the relationship looks like today, and as sociologists, that we project what it could become in the future.

That is why we want to encourage people to leave their mark, to find different alternatives that improve the possibility of existence for humans and non-humans, who since that morning in 2013 have also become our family. It only remains to say that harvesters and artisans make the objects, just as the objects produce harvesters and artisans, and it is there, in these complex networks of production, diffusion and marketing that are established between subject(s)-object(s) and object(s)-subject(s) where it is necessary to trace the multiple relationships that allow us to better understand what was, is and possibly will be the Barniz de Pasto mopa-mopa as an intangible cultural heritage with urgent safeguarding needs and thus avoid its risk of disappearing.

Final note: we would like to emphasise that in the last paragraph we intentionally have not written ICH in capital letters in an institutional way, but we write ‘intangible cultural heritage’ in full and in lower case. This is because the situation should be reassessed, that is, where and how are the human and non-human beings that allow the existence of

Barniz de Pasto today. The integral view of the relationship between subject(s)-object(s) and nature(s)-culture(s) is necessary; these are words that must be joined without any hierarchy to remind us constantly that we are hybrid beings [

22].

Please note that the original Spanish version of this article is available as Supplementary Materials S1.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Supplementary Materials S1: original text in Spanish.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.P.A.M.; methodology, G.P.A.M.; investigation, M.M.F.F. and G.P.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P.A.M.; writing—review and editing, G.P.A.M.; project administration, M.M.F.F. and G.P.A.M.; funding acquisition, G.P.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by (the Grants for the Development of Research in Cultural Heritage of the Directorate of Heritage and Memory. Call for the National Stimulus Program, Ministry of the Cultures, Arts and Knowledge of the Republic of Colombia, 2023).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to all artisans of Barniz de Pasto, harvesters of mopa-mopa in Mocoa, Ruth Flórez Rodríguez of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Group of the Ministry of Cultures, Arts and Knowledge of the Republic of Colombia; Lucia Burgio, Dana Melchar and Monica Katz, without your help it would not have been possible to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Álvarez-White, María Cecilia. 2022. El Barniz de Pasto: secretos y revelaciones de la técnica. Bogotá: Editorial Uniandes.

- Álvarez-White, María Cecilia, David Cohen, and Mario Omar Fernández. “The Splendour of Glitter: Silver Leaf in barniz de Pasto Objects.” Heritage 6, no. 10 (2023): 6581-6595. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, Federica, Elena Basso, and Monica Katz. “In search of Humboldt’s colors: materials and techniques of a 17th-century lacquered gourd from Colombia.” Heritage Science 8 (2020): 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Basso, E.; McGeachy, A.; Mieites Alonso, M.G.; Pozzi, F.; Radpour, R.; Katz, M. Seventeenth-Century Barniz de Pasto Objects from the Collection of the Hispanic Society Museum & Library: Materiality and Technology. Heritage 2024, 7, 2620-2650. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Monzón, L. 2020. El Barniz de Pasto, evolución histórica-técnica, estudio del diseño y propuesta de restauración y conservación preventiva. Madrid: Escuela Superior de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales ESCRBC.

- Kawamura, Y. “Encuentro multicultural en el arte de barniz de Pasto o la laca del Virreinato del Perú.” Historia y sociedad 35 (2018): 87-112.

- Kawamura, Y. The Art of Barniz de Pasto and Its Appropriation of Other Cultures. Heritage 2023, 6, 3292-3306. [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y.; García Barrios, A. Influence of Japanese Namban Lacquer in New Spain, Focusing on Enconchado Furniture. Heritage 2024, 7, 1472-1495. [CrossRef]

- Gomezjurado, Álvaro José. 2017. El Barniz de Pasto: Testimonio del mestizaje cultural en el suroccidente colombiano 1542-1777. Pasto: Ministerio de Cultura y Fundación Mundo Espiral.

- Newman, R., Kaplan, E. and Derrick, M., 2015. Mopa mopa: scientific analysis and history of an unusual South American resin used by the Inka and artisans in Pasto, Colombia. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 54(3), pp.123-148. [CrossRef]

- Burgio, L., Melchar, D., Strekopytov, S., Peggie, D.A., Di Crescenzo, M.M., Keneghan, B., Najorka, J., Goral, T., Garbout, A. and Clark, B.L., 2018. Identification, characterisation and mapping of calomel as ‘mercury white’, a previously undocumented pigment from South America, and its use on a barniz de Pasto cabinet at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Microchemical Journal, 143, pp.220-227. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N., Burgio, L. and Melchar, D., 2020. One small corner of the Viceroyalty in South Kensington: barniz de Pasto at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. In Anales del Museo de América (No. 28, pp. 147-156). Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones.

- Melchar, D.; Burgio, L.; Fernandez, V.; Keneghan, B.; Newman, R. A collaborative, multidisciplinary and multi-analytical approach to the characterisation of barniz de Pasto objects from the V&A collections. In Transcending Boundaries: Integrated Approaches to Conservation. ICOM-CC 19th Triennial Conference Preprints, Proceedings of the ICOM-CC, Beijing, China, 17–21 May 2021; International Council of Museums: Paris, France, 2021.

- Geminiani, L.; Sanchez Carvajal, M.; Schmuecker, E.; Wheeler, M.; Burgio, L.; Melchar, D.; Risdonne, V. A Recently Identified Barniz Brillante Casket at Bateman’s, the Home of Rudyard Kipling. Heritage 2024, 7, 1569-1588. [CrossRef]

- Zabía de la Mata, A. New Contributions Regarding the Barniz de Pasto Collection at the Museo de América, Madrid. Heritage 2024, 7, 667-682. [CrossRef]

- Mora Osejo, Luís Eduardo. 1977. “El Barniz de Pasto”, en Caldasia, Volumen XI, Número 55, enero 20 de 1977. Available on https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/%20cal/article/%20view/34354/34572 (last accessed 10 September 2023).

- Newman, R.; Kaplan, E.; Álvarez-White, M.C. The Story of Elaeagia Resin (Mopa-Mopa), So Far. Heritage 2023, 6, 4320-4344. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Culture, 2019. Plan Especial de Salvaguardia PES, Conocimientos y técnicas tradicionales asociadas con el Barniz de Pasto mopa–mopa, Putumayo-Nariño. Available on: https://patrimonio.mincultura.gov.co/Documents/PES%20BARNIZ%20MOPA%20MOPA.pdf [Last accessed 30 September 2023].

- Fabian, Johannes. 2019. El tiempo y el otro. Cómo construye su objeto la antropología. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, Ediciones Uniandes; Popayán: Universidad del Cauca.

- Suárez Guava, Luís Alberto *y otros catorce*. 2019. Antropología de objetos, sustancias y potencias. Bogotá: Editorial Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

- Melchar, D.; Burgio, L. and Humphrey, N. “Conservation: revealing a hidden skeleton of death | Barniz de Pasto cabinet | V&A”. London: Victoria and Albert Museum. Available on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-j1g81iM28g [last accessed on 10 November 2023].

- Latour, B. Nunca fuimos modernos: ensayos de antropología simétrica. Siglo XXI editores, 2022.

- Sennett, R. El artesano. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama S. A., 2009.

Notes

| 1 |

We have chosen to use the unifying expression ‘Barniz de Pasto mopa-mopa’ to indicate both the technique and raw material discussed in this work. |

| 2 |

By this term, here and throughout the paper, we intend to refer to the process of recognising mopa-mopa as part of the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding. |

| 3 |

In this article ‘mopa-mopa’ is used exclusively to refer to the buds obtained from Elaeagia Pastoensis Mora, while in other publications the term also refers to the material obtained from Elaeagia Utilis. |

| 4 |

For this article we elaborated the category ‘Home-workshop’: a sacred place, where the master artisan works daily and lives with his or her family; a symbolic space within the same dwelling house that is under his or her authority and has a connotation of respect. It is usually located in the living room, dining room, kitchen, courtyard or terrace. This word differs from House-workshop (which emphasises the physical aspect), School-workshop and Workshop-school (institutional proposals of the Ministry of Cultures and AECID) and Workshop (a space completely separate from the dwelling house that is dedicated exclusively to craft work). |

| 5 |

This included master craftsman Óscar Granja, anthropologist Julián Piedrahita, graphic designer René Quintero Montes, sociologist and audiovisual producer Pablo Vladimir Trejo Obando. |

| 6 |

The wood used include cedar, pine, sajo, red balsam, urapan, among others. |

| 7 |

Confidential information that the masters refrain from discussing with outsiders in order to avoid others copying their work, to secure the market and to increase recognition under their own label. The ‘secrets’ are passed on by the craftspeople to the apprentices and relate to the procurement and particular transformation of the raw material, the decoration and the sale of products. |

| 8 |

In the “maquila” workers assemble parts that will be joined by others to create the final work. This reduces costs. |

Figure 1.

The Galeras volcano and the municipality of Pasto, Department of Nariño, Colombia. Photography by Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 1.

The Galeras volcano and the municipality of Pasto, Department of Nariño, Colombia. Photography by Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 2.

Maestro Gilberto Granja. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2014.

Figure 2.

Maestro Gilberto Granja. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2014.

Figure 7.

Workshop of the turner Efren Taborda. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2019.

Figure 7.

Workshop of the turner Efren Taborda. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2019.

Figure 8.

Workshop of the cabinetmaker Ricardo Mauricio Bolaños. Photography by Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 8.

Workshop of the cabinetmaker Ricardo Mauricio Bolaños. Photography by Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 9.

Master wood carver Guillermo Cuaces. Photography by Carlos René Quintero Montes, 2019.

Figure 9.

Master wood carver Guillermo Cuaces. Photography by Carlos René Quintero Montes, 2019.

Figure 10.

Proposal: Multimodal Corridor Tumaco – Pasto – Puerto Asís – Belem do Pará. BIC, Bank Information Center (2014), Miguel López and Giovany Arteaga (2015).

Figure 10.

Proposal: Multimodal Corridor Tumaco – Pasto – Puerto Asís – Belem do Pará. BIC, Bank Information Center (2014), Miguel López and Giovany Arteaga (2015).

Figure 11.

Montañas-selvas habitat of mopa-mopa. Photography of Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 11.

Montañas-selvas habitat of mopa-mopa. Photography of Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 12.

Mountains and forests of Putumayo, mopa-mopa harvesting process, 2019. © Fundación Mundo Espiral.

Figure 12.

Mountains and forests of Putumayo, mopa-mopa harvesting process, 2019. © Fundación Mundo Espiral.

Figure 13.

Harvester Mery Cerón, on the way to mopa-mopa. Photography of Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 13.

Harvester Mery Cerón, on the way to mopa-mopa. Photography of Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 14.

Pedro Pablo Zuin harvesting mopa-mopa (left), and mopa-mopa ‘block’ (right). Photography of Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 14.

Pedro Pablo Zuin harvesting mopa-mopa (left), and mopa-mopa ‘block’ (right). Photography of Giovany Arteaga Montes, 2022.

Figure 15.

Flowering mushroom vase, author: Maestra Claudia Ximena Mora (left); Andean vase, author: Master Eduardo Muñoz Lora. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2019.

Figure 15.

Flowering mushroom vase, author: Maestra Claudia Ximena Mora (left); Andean vase, author: Master Eduardo Muñoz Lora. © Fundación Mundo Espiral, 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).