Submitted:

19 June 2024

Posted:

20 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

TCGA database analysis

In vitro translation analysis

Cell culture and transfection

Plasmid construction

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

CCK-8 assay

EdU assay

Wound-healing assay

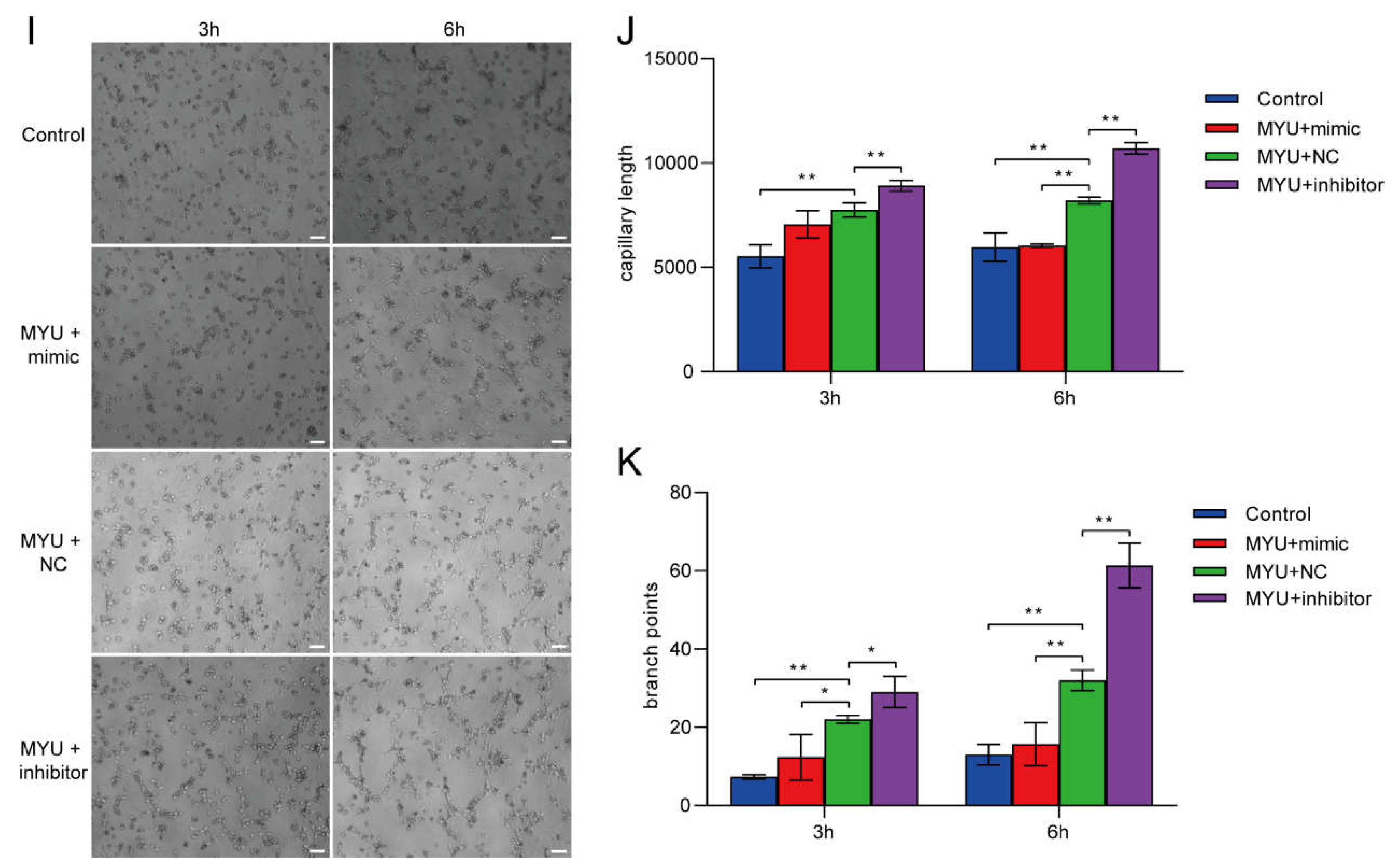

Tube-formation assay

Statistical analysis

Results

1. Expression pattern of MYU and upregulation under hypoxia in vitro

2. HUVEC proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis under hypoxia are promoted by MYU

3. MYU overexpression downregulates miR-23a-3p in HUVECs under hypoxia

4. HUVEC proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis under hypoxia is inhibited by miR-23a-3p overexpression

5. Identification of an MYU–miR-23a-3p–IL-8 axis that regulates angiogenesis under hypoxia

Discussion

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and materials

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BLCA | Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma; |

| BRCA | Breast invasive carcinoma; |

| CESC | Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; |

| COAD | Colon adenocarcinoma; |

| ESCA | Esophageal carcinoma; |

| HNSC | Head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma; |

| KIRC | Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; |

| LGG | Brain Lower Grade Glioma; |

| LIHC | Liver hepatocellular carcinoma; |

| LUAD | Lung adenocarcinoma; |

| LUSC | Lung squamous cell carcinoma; |

| MESO | Mesothelioma; |

| OV | Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; |

| PAAD | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma; |

| PRAD | Prostate adenocarcinoma; |

| READ | Rectum adenocarcinoma; |

| SARC | Sarcoma; |

| SKCM | Skin Cutaneous Melanoma; |

| STAD | Stomach adenocarcinoma; |

| TGCT | Testicular Germ Cell Tumors; |

| THCA | Thyroid carcinoma; |

| UCEC | Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma. |

References

- Zhao X, Nedvetsky P, Stanchi F, et al. Endothelial PKA activity regulates angiogenesis by limiting autophagy through phosphorylation of ATG16L1. Elife, 2019, 8, e46380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang X, Zhang L, Wang S, et al. Exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stem cells promote endothelial cell angiogenesis by transferring miR-125a. J Cell Sci, 2016, 129, 2182–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 3. Tetzlaff F, Adam MG, Feldner A, et al. MPDZ promotes DLL4-induced Notch signaling during angiogenesis. Elife.

- Bower NI, Vogrin AJ, Le Guen L, et al. Vegfd modulates both angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis during zebrafish embryonic development. Development, 2017, 144, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir R, Yaba A, Huppertz B. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in the endometrium during menstrual cycle and implantation. Acta Histochem, 2010, 112, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen DB, Zheng J. Regulation of placental angiogenesis. Microcirculation, 2014, 21, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaniolo K, Sapieha P, Shao Z, et al. Ghrelin modulates physiologic and pathologic retinal angiogenesis through GHSR-1a. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci, 2011, 52, 5376–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodnar, RJ. Chemokine regulation of angiogenesis during wound healing. Adv Wound Care, 2015, 4, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Tumor angiogenesis: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat Med, 2011, 17, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murukesh N, Dive C, Jayson GC. Biomarkers of angiogenesis and their role in the development of VEGF inhibitors. Br J Cancer, 2010, 102, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiani E, Christofori G. Angiopoietins in angiogenesis. Cancer Lett, 2013, 328, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono F, De Smet F, Herbert C, et al. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and growth by a small-molecule multi-FGF receptor blocker with allosteric properties. Cancer Cell, 2013, 23, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadian S, El-Assaad W, Wang XQ, et al. p53 inhibits angiogenesis by inducing the production of Arresten. Cancer Res, 2012, 72, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Chen Y, Lu X-A, et al. Endostatin prevents dietary-induced obesity by inhibiting adipogenesis and angiogenesis. Diabetes, 2015, 64, 2442–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida I, Oliveira GA, Lima M, et al. Different contributions of angiostatin and endostatin in angiogenesis impairment in systemic sclerosis: a cohort study. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2016, 34, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Tumor angiogenesis: MMP-mediated induction of intravasation-and metastasis-sustaining neovasculature. Matrix Biol, 2015, 44, 94–112. [Google Scholar]

- Soufi-Zomorrod M, Hajifathali A, Kouhkan F, et al. MicroRNAs modulating angiogenesis: miR-129-1 and miR-133 act as angio-miR in HUVECs. Tumor Biol, 2016, 37, 9527–9534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang KC, Chang HY. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell, 2011, 43, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voellenkle C, Garcia-Manteiga JM, Pedrotti S, et al. Implication of Long noncoding RNAs in the endothelial cell response to hypoxia revealed by RNA-sequencing. Sci Rep, 2016, 6, 24141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z-C, Tang C, Dong Y, et al. Targeting the long noncoding RNA MALAT1 blocks the pro-angiogenic effects of osteosarcoma and suppresses tumour growth. Int J Biol Sci, 2017, 13, 1398. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann P, Jaé N, Knau A, et al. The lncRNA GATA6-AS epigenetically regulates endothelial gene expression via interaction with LOXL2. Nature communications, 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry H, Harris AL, Mcintyre A. The tumour hypoxia induced non-coding transcriptome. Mol Aspects Med, 2016, 47, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Li Q, Zhang K-S, et al. Downregulation of the long non-coding RNA Meg3 promotes angiogenesis after ischemic brain injury by activating notch signaling. Mol Neurobiol, 2017, 54, 8179–8190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li L, Wang M, Mei Z, et al. lncRNAs HIF1A-AS2 facilitates the up-regulation of HIF-1α by sponging to miR-153-3p, whereby promoting angiogenesis in HUVECs in hypoxia. Biomed Pharmacother, 2017, 96, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin D, Fu C, Sun D. Silence of lncRNA UCA1 represses the growth and tube formation of human microvascular endothelial cells through miR-195. Cell Physiol Biochem, 2018, 49, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou Z-W, Zheng L-J, Ren X, et al. LncRNA NEAT1 facilitates survival and angiogenesis in oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD)-induced brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) via targeting miR-377 and upregulating SIRT1, VEGFA, and BCL-XL. Brain Res, 2019, 1707, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun Y, Xiong X, Wang X. RELA promotes hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells via LINC01693/miR-302d/CXCL12 axis. J Cell Biochem, 2019, 120, 12549–12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Wang P, Xue Y, et al. PVT1 affects growth of glioma microvascular endothelial cells by negatively regulating miR-186. Tumor Biol, 2017, 39, 1010428317694326. [Google Scholar]

- He C, Yang W, Yang J, et al. Long noncoding RNA MEG3 negatively regulates proliferation and angiogenesis in vascular endothelial cells. DNA Cell Biol, 2017, 36, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki Y, Komiya M, Matsumura K, et al. MYU, a target lncRNA for Wnt/c-Myc signaling, mediates induction of CDK6 to promote cell cycle progression. Cell Rep, 2016, 16, 2554–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Xu L, Wang Q, et al. Dysregulation of long non-coding RNA profiles in human colorectal cancer and its association with overall survival. Oncol Lett, 2016, 12, 4068–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau PR, Örd T, Downes NL, et al. Transcriptional profiling of hypoxia-regulated non-coding RNAs in human primary endothelial cells. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2018, 5, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Yang X, Li R, et al. Long non-coding RNA MYU promotes prostate cancer proliferation by mediating the miR-184/c-Myc axis. Oncol Rep, 2018, 40, 2814–2825. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li H, Burnett JC, et al. The role of antisense long noncoding RNA in small RNA-triggered gene activation. RNA, 2014, 20, 1916–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge Y, Yan X, Jin Y, et al. fMiRNA-192 and miRNA-204 directly suppress lncRNA HOTTIP and interrupt GLS1-mediated glutaminolysis in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS Genet, 2015, 11, e1005726. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z-H, Wang W-T, Huang W, et al. The lncRNA HOTAIRM1 regulates the degradation of PML-RARA oncoprotein and myeloid cell differentiation by enhancing the autophagy pathway. Cell Death Differ, 2017, 24, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolia A, Crea F, Xue H, et al. The long non-coding RNA PCGEM1 is regulated by androgen receptor activity in vivo. Mol Cancer, 2015, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X-H, Sun M, Nie F-Q, et al. Lnc RNA HOTAIR functions as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate HER2 expression by sponging miR-331-3p in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer, 2014, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang P, Hu L, Fu G, et al. LncRNA MALAT1 Promotes the Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Melanoma Cells by Downregulating miR-23a. Cancer Manag Res, 2020, 12, 6553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu S, Xu Q. MicroRNA-23a inhibits melanoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in mice through a negative feedback regulation of sdcbp and the MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. IUBMB Life, 2019, 71, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Li B, Fu Y, et al. miR-23a suppresses proliferation of osteosarcoma cells by targeting SATB1. Tumor Biol, 2015, 36, 4715–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen F, Qi S, Zhang X, et al. miR-23a-3p suppresses cell proliferation in oral squamous cell carcinomas by targeting FGF2 and correlates with a better prognosis: miR-23a-3p inhibits OSCC growth by targeting FGF2. Pathology-Research and Practice, 2019, 215, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang S, He W, Wang C. MiR-23a Regulates the Vasculogenesis of Coronary Artery Disease by Targeting Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. Cardiovasc Ther, 2016, 34, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok H-H, Chan L-S, Poon P-Y, et al. Ginsenoside-Rg1 induces angiogenesis by the inverse regulation of MET tyrosine kinase receptor expression through miR-23a. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2015, 287, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu X-D, Guo T, Liu L, et al. MiR-23a targets RUNX2 and suppresses ginsenoside Rg1-induced angiogenesis in endothelial cells. Oncotarget, 2017, 8, 58072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sruthi T, Edatt L, Raji GR, et al. Horizontal transfer of miR-23a from hypoxic tumor cell colonies can induce angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol, 2018, 233, 3498–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng Y, Liu L, Chen C, et al. The extracellular vesicles secreted by lung cancer cells in radiation therapy promote endothelial cell angiogenesis by transferring miR-23a. PeerJ, 2017, 5, e3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu Y, Hung J, Chang W, et al. Hypoxic lung cancer-secreted exosomal miR-23a increased angiogenesis and vascular permeability by targeting prolyl hydroxylase and tight junction protein ZO-1. Oncogene, 2017, 36, 4929–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao L, You B, Shi S, et al. Metastasis-associated miR-23a from nasopharyngeal carcinoma-derived exosomes mediates angiogenesis by repressing a novel target gene TSGA10. Oncogene, 2018, 37, 2873–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Accession No. | Primers | Sequence |

| MYU | ENST00000562866.1 | F | 5’ ATGGGTAACCAGGGGTCAAG 3’ |

| R | 5’ AGTAACAGTGGTAGAGCCGAC 3’ | ||

| IL8 | ENST00000307407.8 | F | 5’ ACTGAGAGTGATTGAGAGTGGAC 3’ |

| R | 5’ AACCCTCTGCACCCAGTTTTC 3’ | ||

| HIF1α | ENST00000539097.2 | F | 5’ TCCAAGAAGCCCTAACGTGT 3’ |

| R | 5’ TGATCGTCTGGCTGCTGTAA 3’ | ||

| VEGF-A | ENST00000372067.7 | F | 5’ ATGCGGATCAAACCTCACCA 3’ |

| R | 5’ CACCAACGTACACGCTCCAG 3’ | ||

| GAPDH | ENST00000396861.5 | F | 5’ GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT 3’ |

| R | 5’ GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGGA 3’ | ||

| U6 | NR_004394.1 | F | 5’ CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA 3’ |

| R | 5’ AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT 3’ | ||

| hsa-miR-23a-3p | MIMAT0000078 | F | 5’ ATCACATTGCCAGGGATTTCC 3’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).