Submitted:

19 June 2024

Posted:

20 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Procedure

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Volume and Prevalence of the Research Literature Production

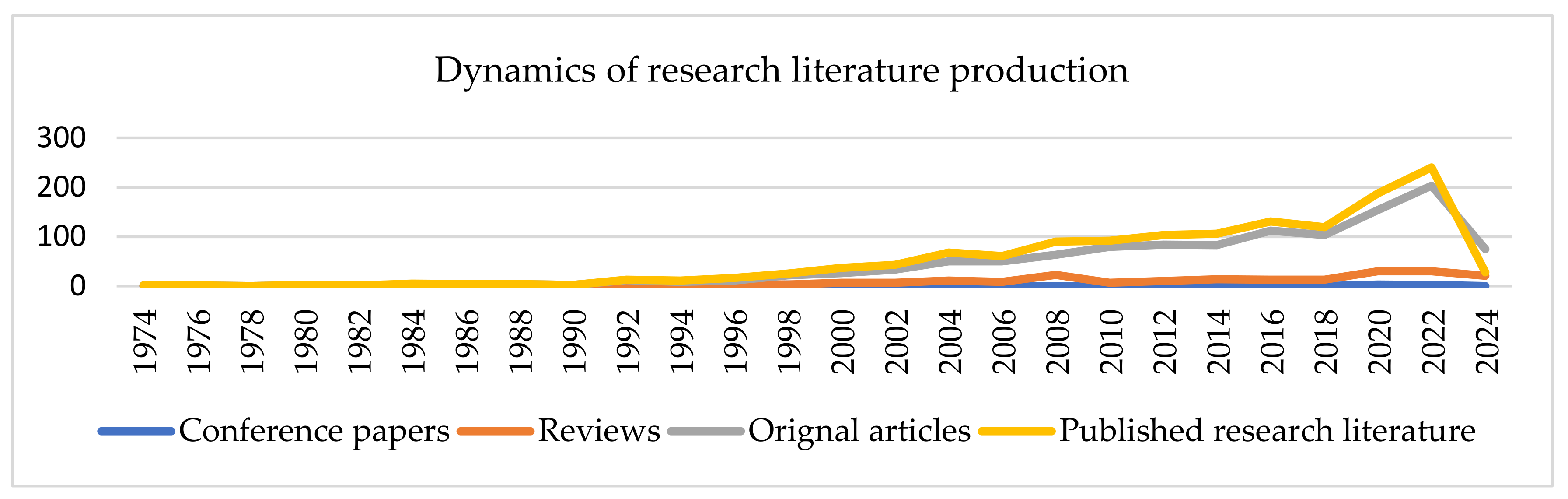

3.2. The Dynamics of the research Literature Production

3.3. The Thematic Analysis

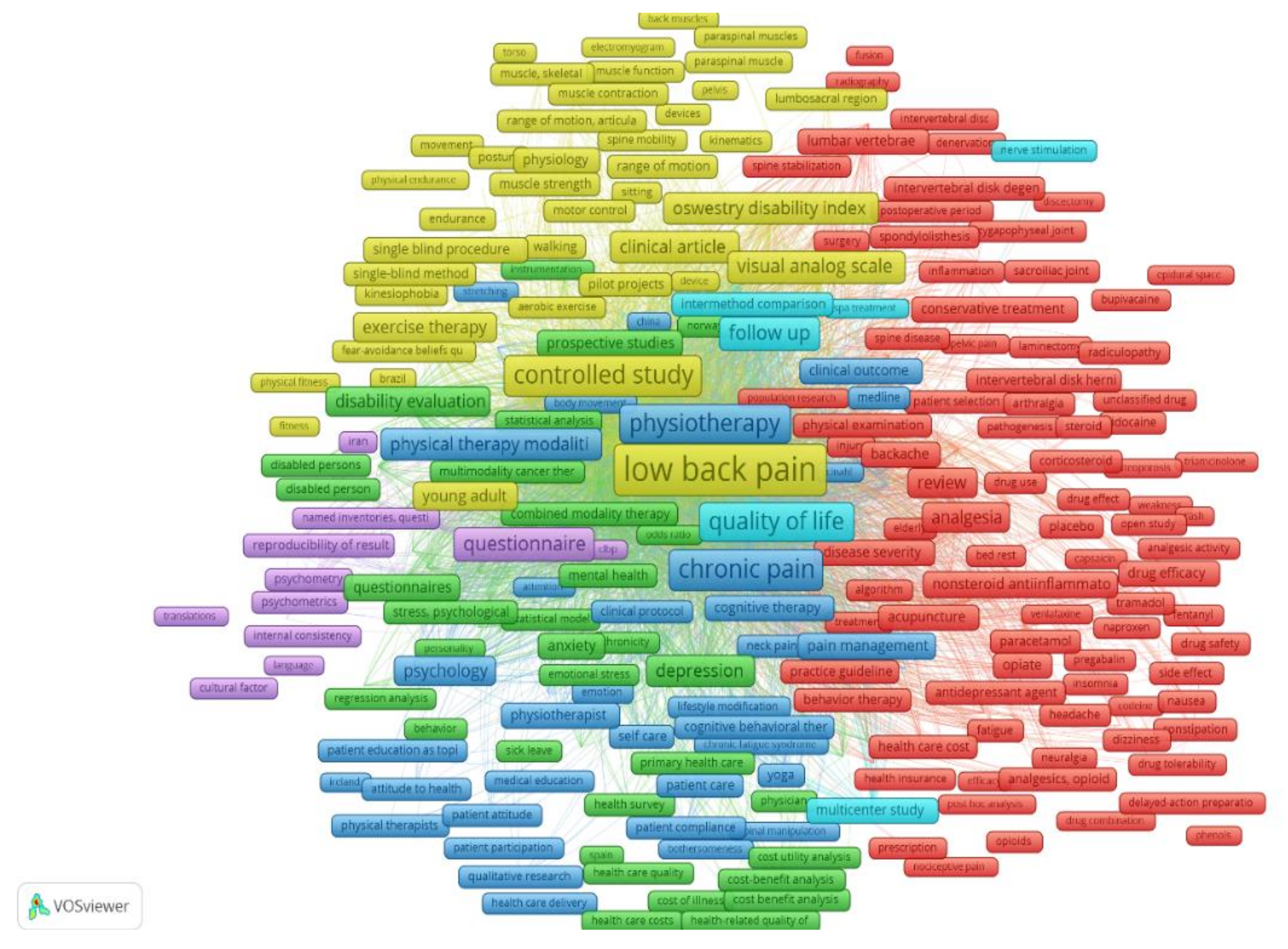

- Pathophysiology of CLBP and the assessment tools (yellow). This cluster contains terms about Oswestry disability index, pilot studies, single-blind method, exercise therapy, pathophysiology, range of motion, spine mobility, etc.

- Diagnostics and CLBP treatment (red). This cluster scopes terms about MRI, diagnostic imaging, conservative treatment, risk assessment, radiculopathy, herniation, operation, etc.

- Questionnaires and surveys about the CLBP (violet). This cluster include terms, connected to reproducibility, validity, assessment, rating scale, catastrophizing, nerve blockade, etc.

- Quality of life (light blue). This cluster covers terms, related to sleep quality, quality of life, functional status, treatment outcome, neuromodulation, balneotherapy, etc..

- Complementary methods in Physiotherapy (dark blue). This cluster contains terms, connected to physical therapy modalities, clinical protocol, yoga, cognitive behavioural therapy, coping behaviour, interpersonal communication, mindfulness, lifestyle, etc.

- Psychosocioeconomic aspects (green). This cluster include terms, such as cost-benefit analysis, health care costs, sick leave, social aspect, psychotherapy, depression, prognosis, etc..

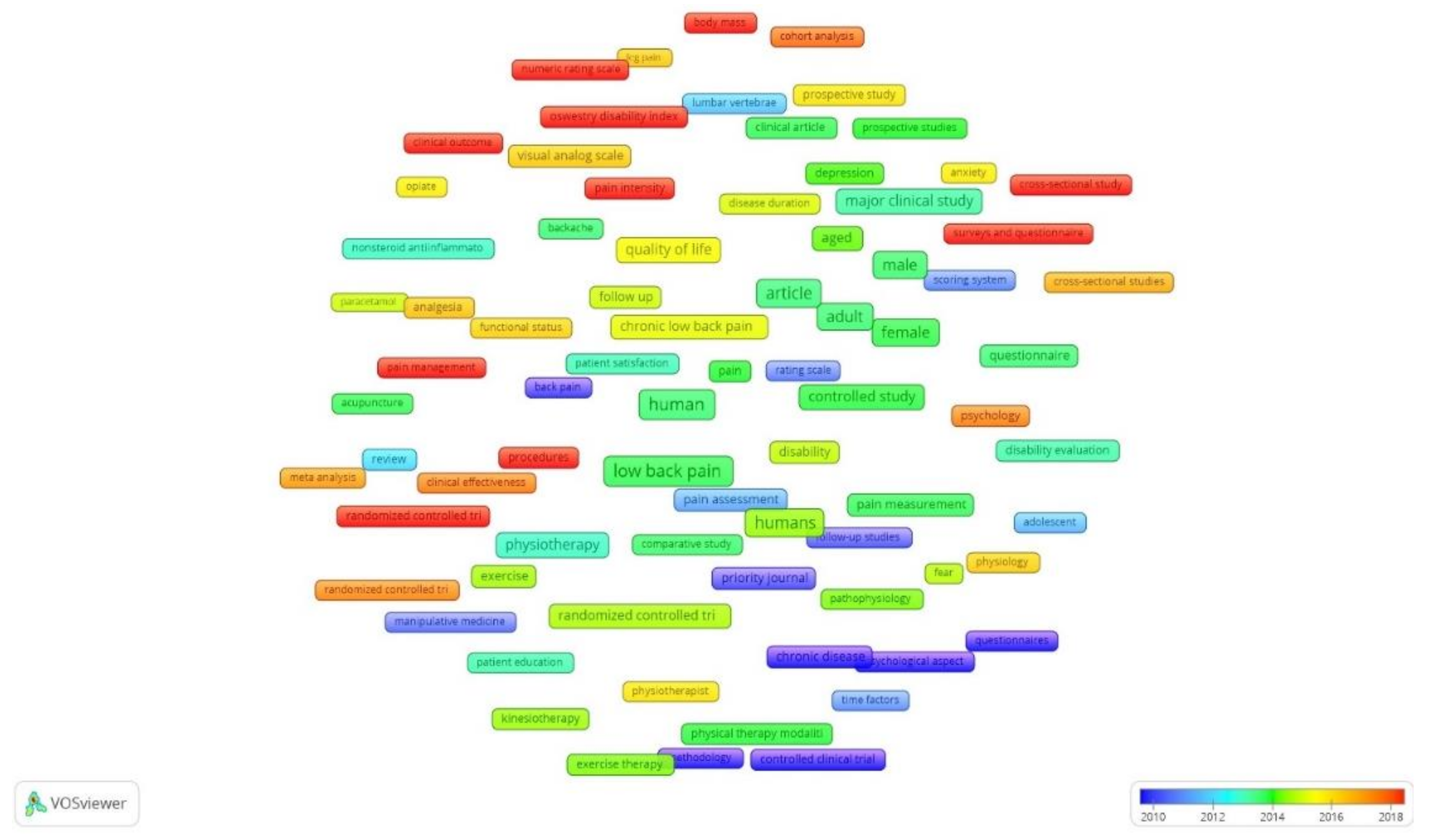

3.4. The Chronological Analysis

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gedin, F.; Alexanderson, K.; Zethraeus, N.; Karampampa, K. Productivity Losses among People with Back Pain and among Population-Based References: A Register-Based Study in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2020, 10, e036638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanciu, L.-E.; Petcu, L.C.; Apostol, S.; Ionescu, E.-V.; Oprea, D.; Oprea, C.; Țucmeanu, E.-R.; Iliescu, M.-G.; Popescu, M.-N.; Obada, B. The Influence of Low Back Pain on Health – Related Quality of Life and the Impact of Balneal Treatment. Balneo PRM Res. J. 2021, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Kidwai, A.; Rakhamimova, E.; Elias, M.; Caldwell, W.; Bergese, S.D. Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Pain. Diagnostics. 2023, 13, 3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Middelkoop, M.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Kuijpers, T.; Verhagen, A.P.; Ostelo, R.; Koes, B.W.; van Tulder, M.W. A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Physical and Rehabilitation Interventions for Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.T.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Guzman, J.; van Tulder, M.W. Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation for Chronic Low Back Pain: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ. 2015, 350, h444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdle, B.; Molander, P.; Stenberg, G.; Stalnacke, B.-M.; Enthoven, P. Weak Outcome Predictors of Multimodal Rehabilitation at One-Year Follow-up in Patients with Chronic Pain-a Practice Based Evidence Study from Two SQRP Centres. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan-Yee Ho, E.; Chen, L.; Simic, M.; Ashton-James, C.E.; Comachio, J.; Xin Mo Wang, D.; Hayden, J.A.; Loureiro Ferreira, M.; Henrique Ferreira, P. Psychological Interventions for Chronic, Non-Specific Low Back Pain: Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis. BMJ. 2022, 376, e067718. [Google Scholar]

- Monticone, M.; Vullo, S.S.; Lecca I, L.; Meloni, F.; Portoghese, I.; Campagna, M. Effectiveness of Multimodal Exercises Integrated with Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Working Patients with Chronic Neck Pain: Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial with 1-Year Follow-Up. Trials. 2022, 23, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, S.; Gilam, G.; Darnall, B.; Goldin, P.; Kong, J.-T.; Law, C.; Heirich, M.; Karayannis, N.; Kao, M.-C.; Lu, T.; et al. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Acupuncture in Chronic Low Back Pain: Protocol for Two Linked Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e37823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurak, I.; Delaš, K.; Erjavec, L.; Stare, J.; Locatelli, I. Effects of Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation on Short-Term Pain and Disability in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moral-Munoz, J.A.; Arroyo-Morales, M.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Cobo, M.J. An Overview of Thematic Evolution of Physical Therapy Research Area From 1951 to 2013. Front. Res. Metrics Anal. 2018, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Weng, L.; Peng, M.; Wang, X. Exercise for Low Back Pain: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research from 1980 to 2018. J. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 53, jrm00052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Li, J.; Xiao, B.; Tang, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Fang, F. Bibliometric Analysis of Research Trends on Manual Therapy for Low Back Pain Over Past 2 Decades. J. Pain Res. 2023, 16, 3045–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Kawchuk, G.; Bussières, A.E.; Al Zoubi, F.M.; Hartvigsen, J.; Fu, S.N.; de Luca, K.; Weiner, D.; Karppinen, J.; Samartzis, D.; et al. Trends of Low Back Pain Research in Older and Working-Age Adults from 1993 to 2023: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Pain Res. 2023, 16, 3325–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, W.; Yan, J. Exercise Interventions for Nonspecific Low Back Pain: A Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research from 2018 to 2023. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1390920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blažun Vošner, H.; Železnik, D.; Kokol, P.; Vošner, J.; Završnik, J. Trends in Nursing Ethics Research: Mapping the Literature Production. Nurs Ethics. 2017, 24, 892–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokol, P.; Blažun Vošner, H.; Završnik, J. Application of Bibliometrics in Medicine: A Historical Bibliometrics Analysis. Heal. Info Libr J. 2021, 38, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, A. Statistical Bibliography or Bibliometrics? J. Doc. 1969, 25, 348–349. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, E. The History and Meaning of the Journal Impact Factor. JAMA. 2006, 295, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejasen, C. Historical Bibliometric Analysis: A Case of the Journal of the Siam Society, 1972-1976. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, D.T. Bibliometrics of Electronic Journals in Information Science. Inf. Res. 2001, 7, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Železnik, U.; Kokol, P.; Starc, J.; Železnik, D.; Završnik, J.; Vošner, H.B. Research Trends in Motivation and Weight Loss: A Bibliometric-Based Review. Healthcare. 2023, 11, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokol, P.; Blažun Vošner, H.; Završnik, J.; Žlahtič, G. Sleeping Beauties in Health Informatics Research. Scientometrics. 2022, 127, 5073–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Završnik, J.; Kokol, P.; Žlahtič, B.; Blažun Vošner, H. Artificial Intelligence and Pediatrics: Synthetic Knowledge Synthesis. Electronics. 2024, 13, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual 2013.

- Gore, M.; Sadosky, A.; Stacey, B.R.; Tai, K.-S.; Leslie, D. The Burden of Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine. 2012, 37, E668–E677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisker, A.; Langberg, H.; Petersen, T.; Mortensen, O.S. Effects of an Early Multidisciplinary Intervention on Sickness Absence in Patients with Persistent Low Back Pain—a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanabria-Mazo, J.P.; D’Amico, F.; Cardeñosa, E.; Ferrer, M.; Edo, S.; Borràs, X.; McCracken, L.M.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Sanz, A.; Luciano, J.V. Economic Evaluation of Videoconference Group Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Behavioral Activation Therapy for Depression Versus Usual Care Among Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain Plus Comorbid Depressive Symptoms. J. Pain. 2024. S1526-5900(24)00351-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahl, C.; Cleland, J.A. Visual Analogue Scale, Numeric Pain Rating Scale and the McGill Pain Questionnaire: An Overview of Psychometric Properties. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2005, 10, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjermstad, M.J.; Fayers, P.M.; Haugen, D.F.; Caraceni, A.; Hanks, G.W.; Loge, J.H.; Fainsinger, R.; Aass, N.; Kaasa, S. Studies Comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for Assessment of Pain Intensity in Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2011, 41, 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.G.; Gray, H.G.; Newton, M.; Granat, M.H. Pain Biology Education and Exercise Classes Compared to Pain Biology Education Alone for Individuals with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, A.S. Physiotherapeutic Treatment Associated with Neuroscience of Pain Education for Patients with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain - Single-Blind Randomized Pilot Clinical Trial. Ağrı - J. Turkish Soc. Algol. 2023, 35, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Li, Y.; Dou, W.; Zhu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zou, Y. Ultra-Short Echo Time MR Imaging in Assessing Cartilage Endplate Damage and Relationship between Its Lesion and Disc Degeneration for Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. BMC Med. Imaging. 2023, 23, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.; Chang, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Zuo, J.; Ni, H.; Xie, B.; Yao, J.; Xu, Z.; Bian, S.; et al. The Enhanced Connectivity between the Frontoparietal, Somatomotor Network and Thalamus as the Most Significant Network Changes of Chronic Low Back Pain. Neuroimage. 2024, 290, 120558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaron, R.V.; Mun, C.J.; McGill, L.S.; Finan, P.H.; Campbell, C.M. The Longitudinal Relationship Between Emotion Regulation and Pain-Related Outcomes: Results From a Large, Online Prospective Study. J. Pain. 2022, 23, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Linton, S.J. Fear-Avoidance and Its Consequences in Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A State of the Art. Pain. 2000, 85, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, M.; Uchida, K.; Takano, S.; Nakawaki, M.; Sekiguchi, H.; Nakazawa, T.; Imura, T.; Saito, W.; Shirasawa, E.; Kawakubo, A.; et al. Role of CD14-positive Cells in Inflammatory Cytokine and Pain-related Molecule Expression in Human Degenerated Intervertebral Discs. J. Orthop. Res. 2021, 39, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.R.; Norvell, D.C.; Hermsmeyer, J.T.; Bransford, R.J.; DeVine, J.; McGirt, M.J.; Lee, M.J. Evaluating Common Outcomes for Measuring Treatment Success for Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine. 2011, 36, S54–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarotto, A.; Maxwell, L.J.; Terwee, C.B.; Wells, G.A.; Tugwell, P.; Ostelo, R.W. Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and Oswestry Disability Index: Which Has Better Measurement Properties for Measuring Physical Functioning in Nonspecific Low Back Pain? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 1620–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, S.J.; Bergbom, S. Understanding the Link between Depression and Pain. Scand. J. Pain. 2011, 2, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, N.C.; Bailey, S.J.; LaChapelle, D.L.; Harman, K.; Hadjistavropoulos, T. Coping Styles, Pain Expressiveness, and Implicit Theories of Chronic Pain. J. Psychol. 2015, 149, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.H.; Kim, H.D.; Shin, H.H.; Huh, B. Assessment of Depression, Anxiety, Sleep Disturbance, and Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain in Korea. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2014, 66, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, P.; Val, P.; Lapuente-Hernández, D.; Cuenca-Zaldívar, J.N.; Calvo, S.; Gómez-Trullén, E.M. Effects of Lifestyle Interventions on the Improvement of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2024, 12, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.; Ostelo, R.; Guzman, J.; van Tulder, M. Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation for Chronic Low Back Pain: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ. 2015, 350, h444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanhope, J.; Breed, M.F.; Weinstein, P. Exposure to Greenspaces Could Reduce the High Global Burden of Pain. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemani, S.; Sarrafzadeh, J.; Dehkordi, S.N.; Talebian, S.; Salehi, R.; Zarei, J. Effect of Multidimensional Physiotherapy on Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv. Rheumatol. 2023, 63, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-H.; Tam, K.-W.; Yang, Y.-L.; Liou, T.-H.; Hsu, T.-H.; Rau, C.-L. Meditation-Based Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Med. 2022, 23, 1800–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.M.; Ferreira, P.H.; Maher, C.G.; Latimer, J.; Ferreira, M.L. The Influence of the Therapist-Patient Relationship on Treatment Outcome in Physical Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, C.H.; Bright, F.A.S.; Mooney, S. The Role and Function of Body Communication in Physiotherapy Practice: A Qualitative Thematic Synthesis. New Zeal. J. Physiother. 2024, 52, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, M.C.; Čeko, M.; Low, L.A. Cognitive and Emotional Control of Pain and Its Disruption in Chronic Pain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henschke, N.; Kamper, S.J.; Maher, C.G. The Epidemiology and Economic Consequences of Pain. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 310 Diseases and Injuries, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016, 388, 1545–1602.

- Bingefors, K.; Isacson, D. Epidemiology, Co-Morbidity, and Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life of Self-Reported Headache and Musculoskeletal Pain – a Gender Perspective. Eur. J. Pain. 2004, 8, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, J.A.; Stewart, W.F.; Chee, E.; Leotta, C.; Foley, K.; Hochberg, M.C. Back Pain Exacerbations and Lost Productive Time Costs in United States Workers. Spine. 2006, 31, 3052–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.O.P.; Maher, C.G.; Latimer, J.; Ferreira, P.H.; Ferreira, M.L.; Pozzi, G.C.; Freitas, L.M.A. Clinimetric Testing of Three Self-Report Outcome Measures for Low Back Pain Patients in Brazil. Spine. 2008, 33, 2459–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, H.; McIntosh, G. Low Back Pain (Chronic). BMJ Clin Evid. 2008, 10, 1116. [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Haldeman, S. Synthesis of Recommendations for the Assessment and Management of Low Back Pain from Recent Clinical Practice Guidelines. Spine J. 2010, 10, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canjuga, M.; Läubli, T.; Bauer, G.F. Can the Job Demand Control Model Explain Back and Neck Pain? Cross-Sectional Study in a Representative Sample of Swiss Working Population. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2010, 40, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R. Will This Patient Develop Persistent Disabling Low Back Pain? JAMA. 2010, 303, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edit, V.; Eva, S.; Maria, K.; Istvan, R.; Agnes, C.; Zsolt, N.; Eva, P.; Laszlo, H.; Peter, T.I.; Emese, K.; et al. Psychosocial, Educational, and Somatic Factors in Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain. Rheumatol. Int. 2013, 33, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo-Cruz, B.; Gusi, N.; Del Pozo-Cruz, J.; Adsuar, J.C.; Hernandez-Mocholí, M.; Parraca, J.A. Clinical Effects of a Nine-Month Web-Based Intervention in Subacute Non-Specific Low Back Pain Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2013, 27, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaafsma FG, W.K. van der B.A.J. van der E.L.C.O.A.; Verbeek, J.H. Physical Conditioning as Part of a Return to Work Strategy to Reduce Sickness Absence for Workers with Back Pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, CD001822. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman, S.; Beggs, T.R. Yoga for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials/Le Yoga Pour Soulager Les Douleurs Lombaires : Une Méta-Analyse d’essais Aléatoires et Contrôlés. Pain Res. Manag. J. Can. Pain Soc. 2013, 18, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomp, S.; Fleig, L.; Schwarzer, R.; Lippke, S. Effects of a Self-Regulation Intervention on Exercise Are Moderated by Depressive Symptoms: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Int. J. Clin. Heal. Psychol. 2013, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inani, S.B.; Selkar, S.P. Effect of Core Stabilization Exercises versus Conventional Exercises on Pain and Functional Status in Patients with Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2013, 26, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notarnicola, A.; Fischetti, F.; Maccagnano, G.; Comes, R.; Tafuri, S.; Moretti, B. Daily Pilates Exercise or Inactivity for Patients with Low Back Pain: A Clinical Prospective Observational Study. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 50, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.C.; Wanigasekera, V.; Tracey, I. Imaging Opioid Analgesia in the Human Brain and Its Potential Relevance for Understanding Opioid Use in Chronic Pain. Neuropharmacology. 2014, 84, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, L.A.; Bittencourt, J.V.; Pagnez, M.A.M.; Mathieson, S.; Saragiotto, B.T.; Telles, G.F.; Meziat-Filho, N.; Nogueira, L.A.C.; Marshall, A.; Joyce, C.T.; et al. Examining What Factors Mediate Treatment Effect in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Mediation Analysis of a Cognitive Functional Therapy Clinical Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 21, 1765–1774. [Google Scholar]

- Roddy, E.; Zwierska, I.; Jordan, K.P.; Dawes, P.; Hider, S.L.; Packham, J.; Stevenson, K.; Hay, E.M.; Ferreira, M.L.S.; Pereira, M.G.; et al. Examining What Factors Mediate Treatment Effect in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Mediation Analysis of a Cognitive Functional Therapy Clinical Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 21, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar]

- Goossens, M.E.J.B.; de Kinderen, R.J.A.; Leeuw, M.; de Jong, J.R.; Ruijgrok, J.; Evers, S.M.A.A.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S. Is Exposure in Vivo Cost-Effective for Chronic Low Back Pain? A Trial-Based Economic Evaluation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ickmans, K.; Moens, M.; Putman, K.; Buyl, R.; Goudman, L.; Huysmans, E.; Diener, I.; Logghe, T.; Louw, A.; Nijs, J. Back School or Brain School for Patients Undergoing Surgery for Lumbar Radiculopathy? Protocol for a Randomised, Controlled Trial. J. Physiother. 2016, 62, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caby, I.; Olivier, N.; Janik, F.; Vanvelcenaher, J.; Pelayo, P. A Controlled and Retrospective Study of 144 Chronic Low Back Pain Patients to Evaluate the Effectiveness of an Intensive Functional Restoration Program in France. Healthc. 2016, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.E.; Moore, T.J.; Learman, K.; Showalter, C.; Snodgrass, S.J. Can Experienced Physiotherapists Identify Which Patients Are Likely to Succeed with Physical Therapy Treatment? Arch. Physiother. 2015, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Synnott, A.; O’Keeffe, M.; Bunzli, S.; Dankaerts, W.; O’Sullivan, P.; O’Sullivan, K. Physiotherapists May Stigmatise or Feel Unprepared to Treat People with Low Back Pain and Psychosocial Factors That Influence Recovery: A Systematic Review. J. Physiother. 2015, 61, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, A.; Hall, A.M.; Williams, G.C.; McDonough, S.M.; Ntoumanis, N.; Taylor, I.M.; Jackson, B.; Matthews, J.; Hurley, D.A.; Lonsdale, C. Effect of a Self-Determination Theory-Based Communication Skills Training Program on Physiotherapists’ Psychological Support for Their Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driver, C.; Kean, B.; Oprescu, F.; Lovell, G.P. Knowledge, Behaviors, Attitudes and Beliefs of Physiotherapists towards the Use of Psychological Interventions in Physiotherapy Practice: A Systematic Review. Disabil Rehabil. 2017, 39, 2237–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raheel, H. Depression and Associated Factors among Adolescent Females in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, a Cross-sectional Study. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borys, C.; Lutz, J.; Strauss, B.; Altmann, U. Effectiveness of a Multimodal Therapy for Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain Regarding Pre-Admission Healthcare Utilization. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, T.; Komatsu, H.; Rosenzweig, M.Q.; Chohnabayashi, N.; Nishimura, N.; Oizumi, S.; Ren, D. Impact of Symptom Clusters on Quality of Life Outcomes in Patients from Japan with Advanced Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancers. Asia-Pacific J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 3, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compare, A.; Marchettini, P.; Zarbo, C. Risk Factors Linked to Psychological Distress, Productivity Losses, and Sick Leave in Low-Back-Pain Employees: A Three-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study. Pain Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 3797493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsook, D.; Linnman, C.; Faria, V.; Strassman, A.M.; Becerra, L.; Elman, I. Reward Deficiency and Anti-Reward in Pain Chronification. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 68, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansell, G.; Hill, J.C.; Main, C.; Vowles, K.E.; van der Windt, D. Exploring What Factors Mediate Treatment Effect: Example of the STarT Back Study High-Risk Intervention. J.Pain. 2016, 17, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.T.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Guzman, J.; van Tulder, M.W. Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation for Chronic Low Back Pain: Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ. 2015, 350, h444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamam, D.M.; Leaver, A.; Moloney, N.; Alsobayel, H.I.; Alashaikh, G.; Mackey, M.G. Pain Behaviour Scale (PaBS): An Exploratory Study of Reliability and Construct Validity in a Chronic Low Back Pain Population. Pain Res. Manag. J. Can. Pain Soc. 2019, 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Xu, B.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Tian, Z.; Li, D.; Cen, J.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; et al. A Comparison between the Low Back Pain Scales for Patients with Lumbar Disc Herniation: Validity, Reliability, and Responsiveness. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2020, 18, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benz, T.; Lehmann, S.; Elfering, A.; Sandor, P.S.; Angst, F. Comprehensiveness and Validity of a Multidimensional Assessment in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Završnik, J.; Blažun Vošner, H.; Kokol, P.; Pišot, R.; Krečič Javornik, M. Sport Education and Society: Bibliometric Visualization of Taxonomy. J. Phys. Educ. Sport. 2016, 16, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, T.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulkader, R.S.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abebo, T.A.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived with Disability for 328 Diseases and Injuries for 195 Countries, 1990–2016: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, I.M.B. de; Merini, L.R.; Vidal Ramos, L.A.; Pássaro, A. de C.; França, J.I.D.; Marques, A.P. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Associated Factors in Older Adults: Amazonia Brazilian Community Study. Healthcare. 2021, 9, 539. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øverås, C.K.; Johansson, M.S.; de Campos, T.F.; Ferreira, M.L.; Natvig, B.; Mork, P.J.; Hartvigsen, J. Distribution and Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Pain Co-Occurring with Persistent Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021, 22, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartvigsen, J.; Natvig, B.; Ferreira, M. Is It All about a Pain in the Back? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 27, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takasaki, H. Predictors of 1-Year Perceived Recovery, Absenteeism, and Expenses Due to Low Back Pain in Workers Receiving Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy: A Prospective Cohort Study. Healthcare. 2023, 11, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Hoeh, N.H.; Voelker, A.; Gulow, J.; Uhle, U.; Przkora, R.; Heyde, C.-E. Impact of a Multidisciplinary Pain Program for the Management of Chronic Low Back Pain in Patients Undergoing Spine Surgery and Primary Total Hip Replacement: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Patient Saf. Surg. 2014, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furunes, H.; Storheim, K.; Brox, J.I.; Johnsen, L.G.; Skouen, J.S.; Franssen, E.; Solberg, T.K.; Sandvik, L.; Hellum, C. Total Disc Replacement versus Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain and Degenerative Discs: 8-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial. Spine J. 2017, 17, 1480–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nees, T.A.; Riewe, E.; Waschke, D.; Schiltenwolf, M.; Neubauer, E.; Wang, H. Multidisciplinary Pain Management of Chronic Back Pain: Helpful Treatments from the Patients’ Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cholewicki, J.; Breen, A.; Popovich, J.M.; Peter Reeves, N.; Sahrmann, S.A.; Van Dillen, L.R.; Vleeming, A.; Hodges, P.W. Can Biomechanics Research Lead to More Effective Treatment of Low Back Pain? A Point-Counterpoint Debate. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Hui, E.S.; Kranz, G.S.; Chang, J.R.; de Luca, K.; Pinto, S.M.; Chan, W.W.; Yau, S.; Chau, B.K.; Samartzis, D.; et al. Potential Mechanisms Underlying the Accelerated Cognitive Decline in People with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Scoping Review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 82, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashbaum, I.; Sarno, J. Psychosomatic Concepts in Chronic Pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003, 84, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, E.; De Herdt, A.; Minguet, P.; Baldew, S.S.; Probst, M. Can Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Based Strategies Be Integrated into Physiotherapy for the Prevention of Chronic Low Back Pain? A Systematic Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erp, R.M.A.; Huijnen, I.P.J.; Verbunt, J.A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M. A Biopsychosocial Primary Care Intervention (Back on Track) versus Primary Care as Usual in a Subgroup of People with Chronic Low Back Pain: Protocol for a Randomised, Controlled Trial. J. Physiother. 2015, 61, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojmanovska Shukova, D.; Velichkovska, L.A.; Ibrahimi-Kacuri, D. Low Back Pain, Influence of Anxiety in Its Treatment. Res. Phys. Educ. Sport Heal. 2018, 7, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Berković-Šubić, M. Povezanost Depresije, Katastrofiziranja i Jačine Boli s Funkcionalnom Onesposobljenošću Bolesnika s Kroničnom Križoboljom Prije i Nakon Terapijskih Vježbi [PhD Thesis]. 2021, p.16-52.

- Shamji, M.F.; Setton, L.A.; Jarvis, W.; So, S.; Chen, J.; Jing, L.; Bullock, R.; Isaacs, R.E.; Brown, C.; Richardson, W.J. Proinflammatory Cytokine Expression Profile in Degenerated and Herniated Human Intervertebral Disc Tissues. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licciardone, J.C.; Kearns, C.M.; Hodge, L.M.; Bergamini, M.V.W. Associations of Cytokine Concentrations With Key Osteopathic Lesions and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain: Results From the OSTEOPATHIC Trial. J. Osteopath. Med. 2012, 112, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Queiroz, B.Z.; Pereira, D.S.; Lopes, R.A.; Felício, D.C.; Silva, J.P.; de Britto Rosa, N.M.; Dias, J.M.D.; Dias, R.C.; Lustosa, L.P.; Pereira, L.S.M. Association Between the Plasma Levels of Mediators of Inflammation With Pain and Disability in the Elderly With Acute Low Back Pain. Spine. 2016, 41, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Synnott, A.; O’Keeffe, M.; Bunzli, S.; Dankaerts, W.; O’Sullivan, P.; Robinson, K.; O’Sullivan, K. Physiotherapists Report Improved Understanding of and Attitude toward the Cognitive, Psychological and Social Dimensions of Chronic Low Back Pain after Cognitive Functional Therapy Training: A Qualitative Study. J. Physiother. 2016, 62, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukičević, A.; Ogurlić, R.; Lazić, M.; Beqaj, S.; Švraka, E. Patients’ Trust in the Health-Care System and Physiotherapists. J. Heal. Sci. 2021, 11, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Institution | Number of funded publications | Percentage of funded informations sources (in %) |

|---|---|---|

| National Institutes of Health | 84 | 8,97 |

| National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health | 67 | 7,15 |

| Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior | 30 | 3,20 |

| National Health and Medical Research Council | 28 | 2,99 |

| Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo | 23 | 2,46 |

| National Natural Science Foundation of China | 23 | 2,46 |

| Pfizer | 18 | 1,92 |

| U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs | 18 | 1,92 |

| National Institute on Aging | 17 | 1,81 |

| National Institute of Child Health and Human Development | 16 | 1,71 |

| Source title | Number of sources | Percentage of all sources (in %) | IF 20221 | H-index of journal2 | Quartiles (Q)3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spine | 129 | 6,79 | 3.0 | 292 |

|

| BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders | 81 | 4,27 | 2.3 | 122 |

|

| European Spine Journal | 52 | 2,74 | 2.8 | 164 |

|

| Spine Journal | 52 | 2,74 | 4.5 | 136 |

|

| Pain | 51 | 2,69 | 7.4 | 296 |

|

| Journal Of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation | 48 | 2,53 | 1.6 | 39 |

|

| Clinical Journal of Pain | 47 | 2,48 | 2.9 | 145 |

|

| Pain Medicine United States | 46 | 2,42 | No data | No data |

|

| Journal of Pain Research | 44 | 2,32 | 2.7 | 71 |

|

| BMJ Open | 34 | 1,79 | 2.9 | 160 |

|

| Topic (color) | Subtopics | The newest / most cited papers | Focus of research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathophysiology of CLBP and the assessment tools (yellow) | Pain quantification tools, Muscle physiology, Rehabilitation, Kinesiology |

-Visual analogue scale, numeric pain rating scale and the McGill pain Questionnaire: an overview of psychometric properties [29] -Studies Comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for Assessment of Pain Intensity in Adults: A Systematic Literature Review [30] -Pain biology education and exercise classes compared to pain biology education alone for individuals with chronic low back pain: A pilot randomised controlled trial [31] -Physiotherapeutic treatment associated with neuroscience of pain education for patients with chronic non-specific low back pain - single-blind randomized pilot clinical trial [32] -Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation on Short-Term Pain and Disability in Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis [10] |

The VAS and NPRS are the most commonly used scales of perceived pain intensity, but otherwise there is no established gold standard for pain measurement in the literature. Physiotherapy interventions through behavioural (teaching the patient about the biology of their pain) or instructional modalities demonstrate better treatment outcomes for CLBP. |

| Diagnostics and CLBP treatment (red) | Diagnostics, Analgesia, Risk assessment, Pathology, Other treatment methods |

-Ultra-short echo time MR imaging in assessing cartilage endplate damage and relationship between its lesion and disc degeneration for chronic low back pain patients [33] -The enhanced connectivity between the frontoparietal, somatomotor network and thalamus as the most significant network changes of chronic low back pain [34] -The Longitudinal Relationship Between Emotion Regulation and Pain-Related Outcomes: Results From a Large, Online Prospective Study [35] -Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art [36] -Role of CD14-positive cells in inflammatory cytokine and pain-related molecule expression in human degenerated intervertebral discs [37] |

MRI is the most widespread method for researching pain networks in the brain, a newer method is UTE (ultra-short echo time) MRI. Research indirectly suggests a psycho-neuro-immunological connection in CLBP. Pain-related fear and avoidance appear to be essential features for the development of chronic pain. The thalamus plays the most important role in regulation of pain-related emotions. Expression of pain-related molecules is mediated by CD14+ cells via inflammatory cytokines. |

| CLBP Questionnaires and surveys (violet) | Questionnaires and surveys, Pain, Patients’ impact. |

-Evaluating Common Outcomes for Measuring Treatment Success for Chronic Low Back Pain [38] -Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and Oswestry Disability Index: Which Has Better Measurement Properties for Measuring Physical Functioning in Nonspecific Low Back Pain? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [39] -Understanding the link between depression and pain [40] - Coping Styles, Pain Expressiveness, and Implicit Theories of Chronic Pain [41] |

Studies recommend measuring several outcomes to assess the strength of CLBP and the effectiveness of physiotherapy, namely: functional (Oswestry Disability Index, Rolland Morris Disability Index, etc.), pain (NPRS, Pain Disability Index, etc.), psychosocial (Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire) and other (return to work, complications or adverse effects, etc.)) outcomes and quality of life assessment (SF-36, etc.). Negative behavioural emotion regulation is reported to result in spiralling negative affect and subsequent CLBP relapse. |

| Quality of life (light blue) | Quality of life, Intermethod comparison, Newer therapeutic methods |

- Assessment of depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain in Korea [42] - Effects of Lifestyle Interventions on the Improvement of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis [43] - Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis [44] - Exposure to greenspaces could reduce the high global burden of pain [45] |

Depression, anxiety, coping behaviour and catastrophizing are the main components of the quality of life assessment and influence the strength of CLBP and the success of physiotherapy. The concept of a multidisciplinary approach emphasizes the connection between the psychological and physical components of pain. More recent studies are also focused on investigating the effects of the environment and report that a calmer and green living environment should have a positive effect on the expression of CLBP and pain in general. |

| Complementary methods in Physiotherapy (dark blue) | Physiotherapy, Complementary therapies, Personal relationships, Coping behaviour |

- Effect of multidimensional physiotherapy on non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial [46] - Meditation-Based Therapy for Chronic Low Back Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials [47] - The Influence of the Therapist-Patient Relationship on Treatment Outcome in Physical Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review [48] - The role and function of body communication in physiotherapy practice: A qualitative thematic synthesis [49] - Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain [50] |

The physiotherapist-patient relationship plays an important role in the success of physiotherapy, as it affects the patient's trust. The effectiveness of rehabilitation is also influenced by non-verbal communication, the patient's ability to cope with pain and associated relaxation methods (meditation). |

| Psychosocioeconomic aspects (green) | Economy, Absenteeism, Socioeconomic factors, Disability, Risk factors |

- The Epidemiology and Economic Consequences of Pain [51] - Effects of an early multidisciplinary intervention on sickness absence in patients with persistent low back pain—a randomized controlled trial [27] - Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 [52] |

Research shows an increasing prevalence of CLBP and associated health care costs. Early multidisciplinary treatment of CLBP is essential to reduce the rate of sick leave and work disability. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).