Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Needle Litter Collection, Storage, and Mass-Loss Determination

2.3. Sample Preparation and Chemical Analyses

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

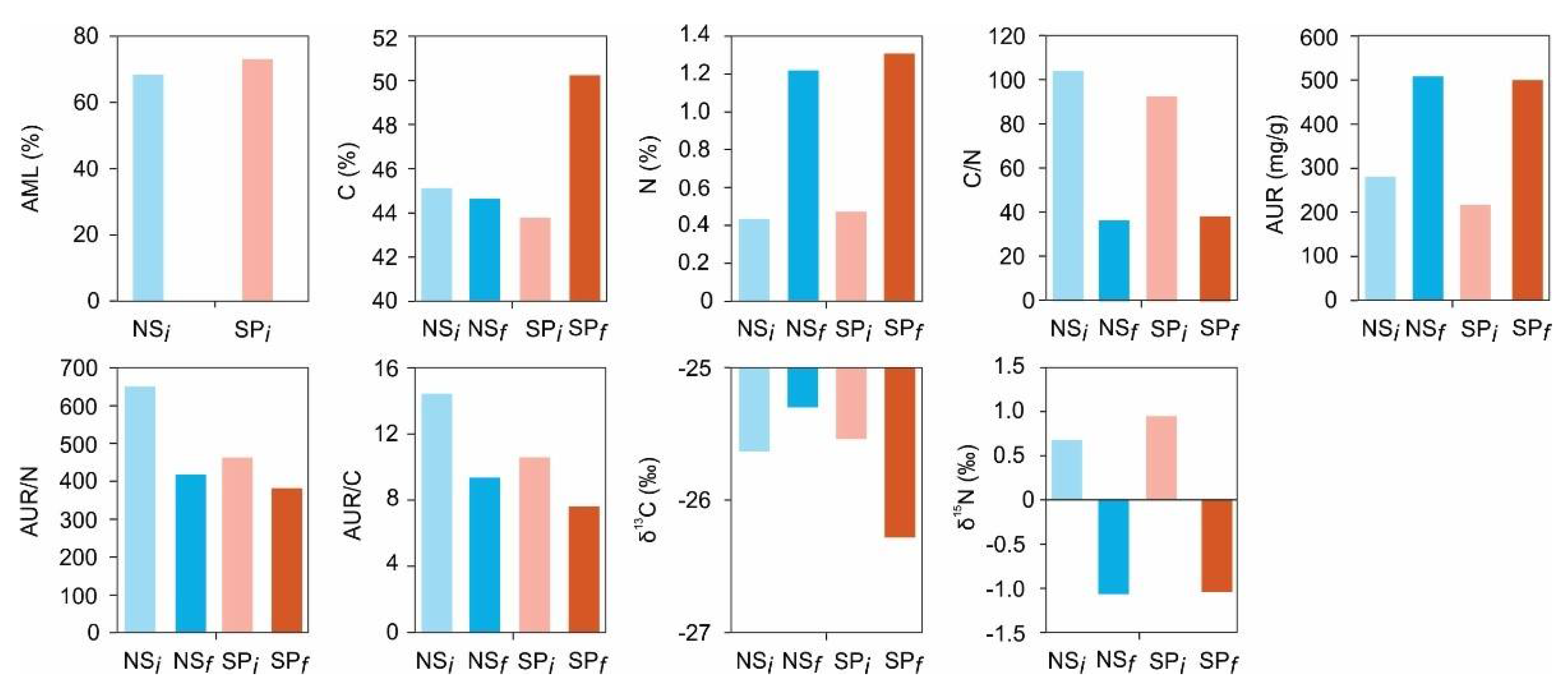

3.1. Initial Litter at Time t0

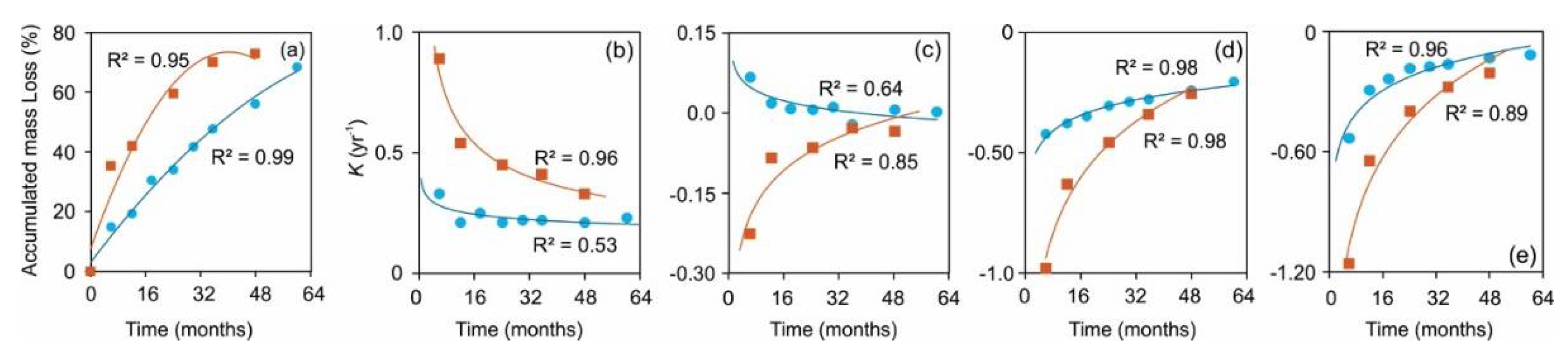

3.2. Litter Mass Loss and Decomposition Dynamics

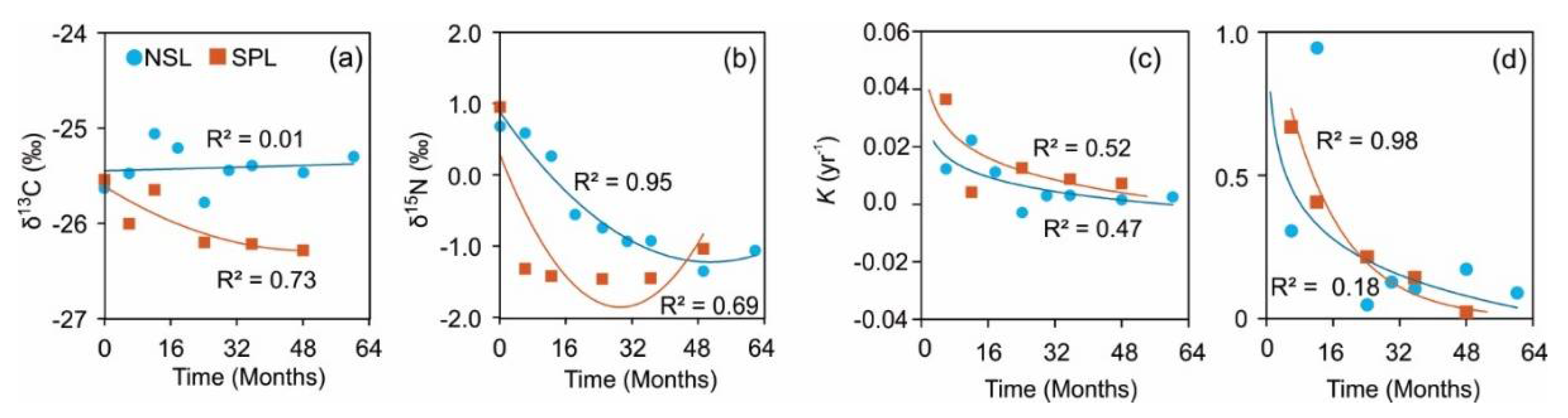

3.3. δ13C Dynamics during Decomposition

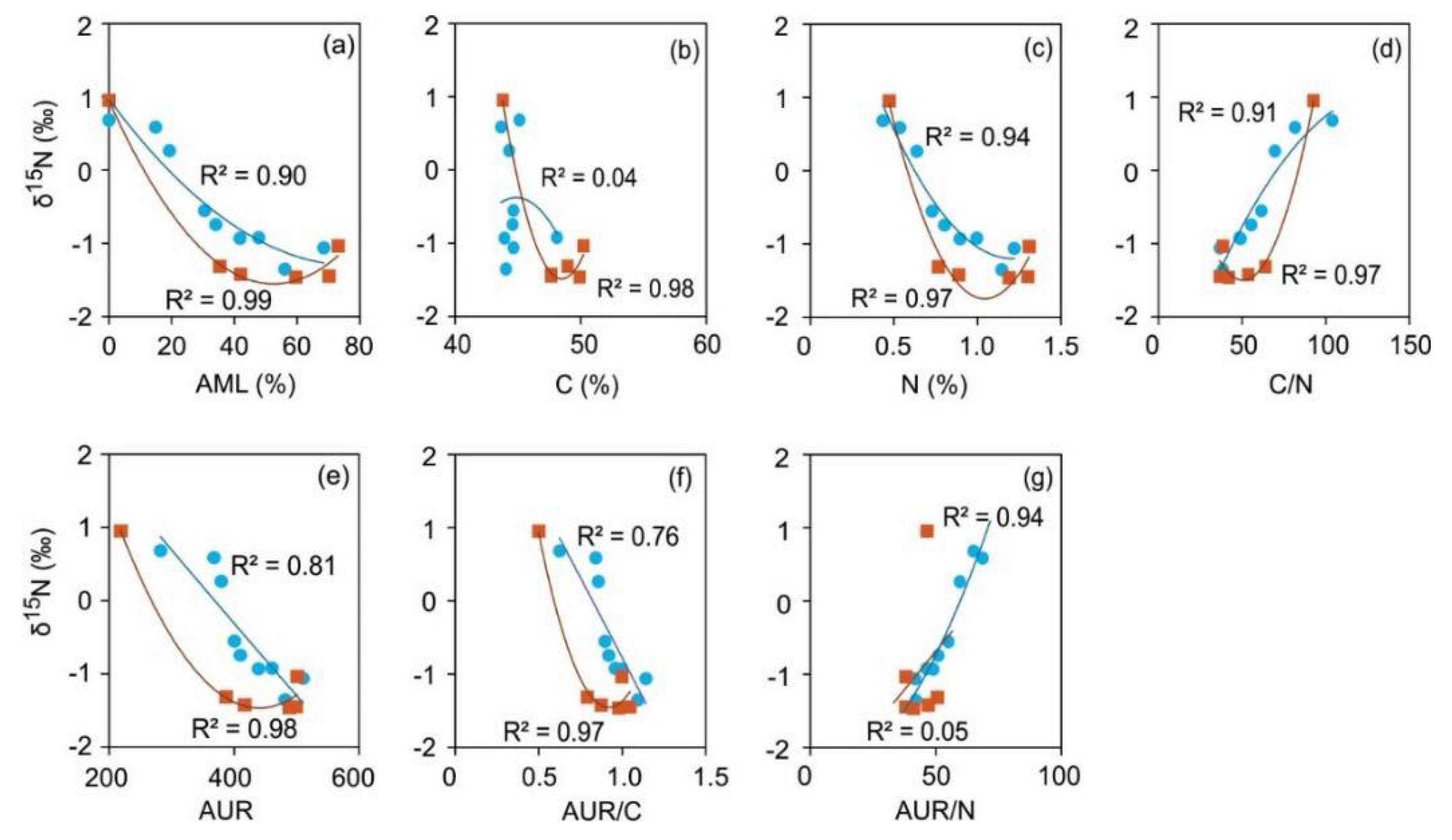

3.4. δ15N dynamics during decomposition

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Change in δ13C with Previous Studies

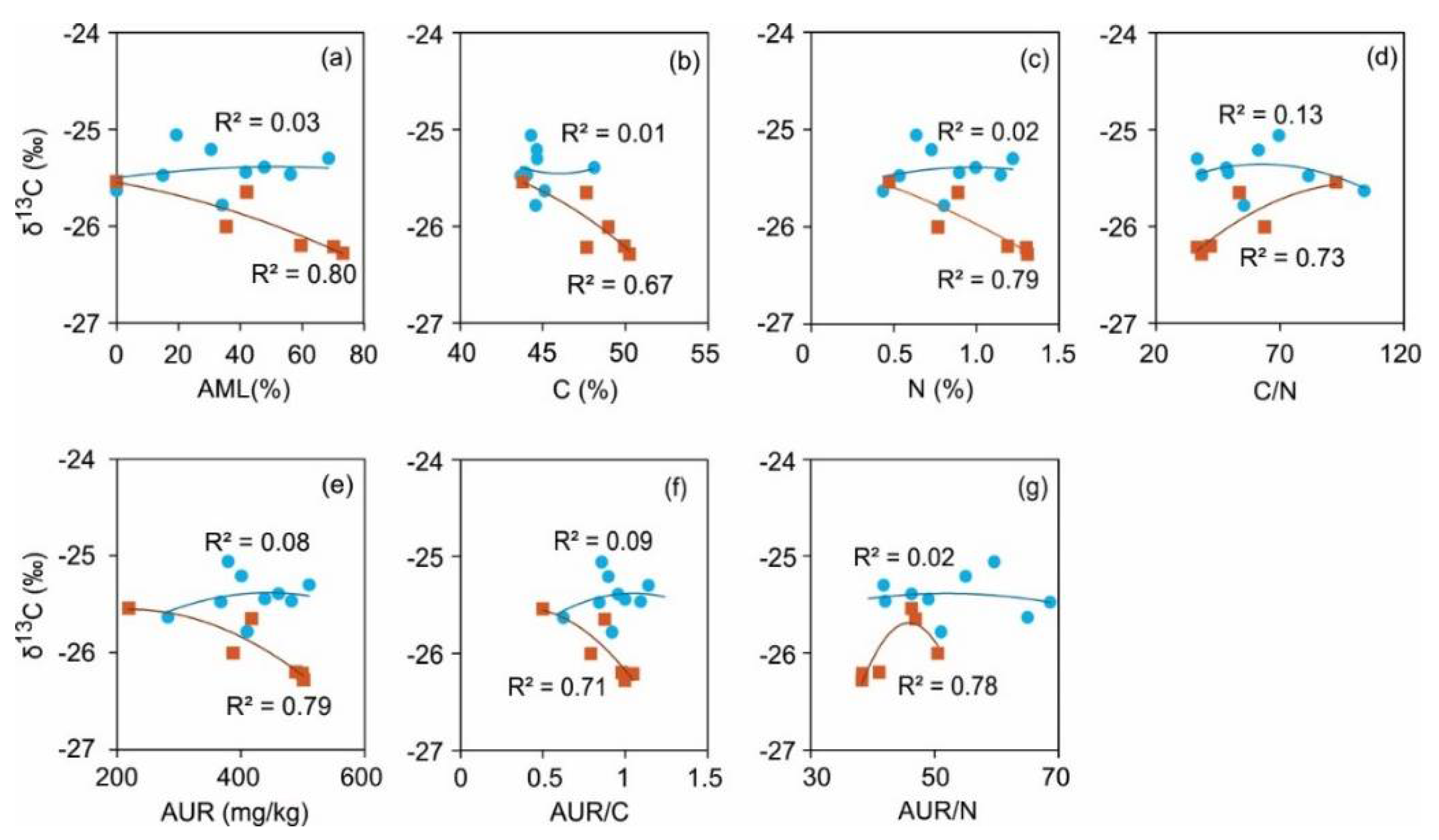

4.2. Factors Influencing δ13C Signatures of Decomposing Litter

4.3. Comparison of Change in δ15N with Previous Studies

4.4. Factors Influencing δ15N Signatures of Decomposing Litter

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berg, B.; Laskowski, R. Litter decomposition, a guide to carbon and nutrient turnover. 2005, Elsevier, New York.

- Balesdent, J.; Girardin, C.; Mariotti, A. Site-related δ13C of tree leaves and soil organic matter in a temperate forest. Ecology 1993, 74, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C.E.; Vesterdal, L.; Preston, C.M.; Simard, S.W. Influence of initial chemistry on decomposition of foliar litter in contrasting forest types in British Columbia. Can. J. For. Res. 2004, 34, 1714–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubino, M.; Lubritto, C.; D’Onofrio, A.; Terrasi, F.; Gleixner, G.; Cotrufo, M.F. An isotopic method for testing the influence of leaf litter quality on carbon fluxes during decomposition. Oecologia 2007, 154, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, B. Decomposition patterns for foliar litter–a theory for influencing factors. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M.K.; Berg, B.; Lee, K.S.; Nilsson, T.; Shin, H.S. Dynamics of trace and rare earth elements during long-term (over 4 years) decomposition in Scots pine and Norway spruce forest stands, Southern Sweden. Front. Env. Sci. 2023, 11, 1190370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connin, S.L.; Feng, X.; Virginia, R.A. Isotopic discrimination during long–term decomposition in an arid land ecosystem. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osono, T.; Takeda, H.; Azuma, J.I. Carbon isotope dynamics during leaf litter decomposition with reference to lignin fractions. Ecol. Res. 2008, 23, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngao, J.; Cotrufo, M.F. Carbon isotope discrimination during litter decomposition can be explained by selective use of substrate with differing δ13C. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 5–82. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Pei, Z. Litter decomposition in a subtropical plantation in Qianyanzhou China. J. For. Res. 2011, 16, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M.K.; Lee, K.S.; Song, B.Y.; Lee, D.; Bong, Y.S. Early-stage changes in natural 13C and 15N abundance and nutrient dynamics during different litter decomposition. J. Plant Res. 2016, 129, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Grandy, A.S.; Harmon, M.E. Isotopic and compositional evidence for carbon and nitrogen dynamics during wood decomposition by saprotrophic fungi. Fungal Ecol. 2020, 45, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Högberg, P. Nitrogen isotopes link mycorrhizal fungi and plants to nitrogen dynamics. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 36–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kammer, A.; Hagedorn, F. Mineralisation leaching and stabilisation of 13C labelled leaf and twig litter in a beech forest soil. Biogeosciences 2011, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G.; Tsujimura, M.; Sugimoto, A.; Davaa, G.; Oyunbaatar, D.; Sugita, M. Temporal variation of δ13C of larch leaves from a montane boreal forest in Mongolia. Trees 2007, 1, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perakis, S.S.; Sinkhorn, E.R.; Compton, J.E. δ15N constraints on long–term nitrogen balances in temperate forests. Oecologia 2011, 167, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, C.; Nault, J.; Trofymow, J. Chemical changes during 6 years of decomposition of 11 litters in some Canadian forest sites Part 2 13C abundance solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy and the meaning of lignin. Ecosystems 2009, 12, 1078–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; McClaugherty, C. Plant litter: Decomposition, humus formation, carbon sequestration. Springer: New York, NY, 2020, 4th Edition.

- Dijkstra, P.; LaViolette, C.M.; Coyle, J.S.; Doucett, R.R.; Schwartz, E.; Hart, S.C.; Hungate, B.A. 15N enrichment as an integrator of the effects of C and N on microbial metabolism and ecosystem function. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, T.; Warner, B.; Aravena, R. Effects of the early stage of decomposition on change in carbon and nitrogen isotopes in Sphagnum litter. J. Plant Interact. 2005, 1, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Fry B Nitrogen isotope studies in forest ecosystems. In, Lajtha K, Michener R. (eds.) Stable isotopes in ecology. Blackwell Scientific Publications:Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 22–44.

- Högberg, P. 15N natural abundance in soil–plant systems. New Phytol. 1997, 137, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templer, P.H.; Arthur, M.A.; Lovett, G.M.; Weathers, K.C. Plant and soil natural abundance δ15N: indicators of relative rates of nitrogen cycling in temperate forest ecosystems. Oecologia 2007, 153, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melillo, J.M.; Aber, J.D.; Linkins, A.E.; Ricca, A.; Fry, B.; Nadelhoffer, K.J. Carbon and nitrogen dynamics along the decay continuum: plant litter to soil organic matter. Plant Soil 1989, 115, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazza, L.; Iacuminm, P.; Siffi, C.; Gerdol, R. Seasonal variation in nitrogen isotopic composition of bog plant litter during 3 years of field decomposition. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2010, 46, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Hobbie, J.E. Natural abundance of 15N in nitrogen–limited forests and tundra can estimate nitrogen cycling through mycorrhizal fungi, a review. Ecosystems 2008, 11, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osono, T.; Hobara, S.; Koba, K.; Kameda, K.; Takeda, H. Immobilization of avian excreta–derived nutrients and reduced lignin decomposition in needle and twig litter in a temperate coniferous forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedin, D.A.; Tieszen, L.L.; Dewey, B.; Pastor, J. Carbon isotope dynamics during grass decomposition and soil organic matter formation. Ecology 1995, 76, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Pei, Z. Litter decomposition in a subtropical plantation in Qianyanzhou, China. J. For. Res. 2011, 16, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, R.; Fogel, M.L.; Sprague, E.K. Diagenesis of belowground biomass of Spartina alterniflora in salt-marsh sediments. Limno. Oceano. 1991, 36, 1358–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, C.M.; Trofymow, J.A.; Flanagan, L.B. Decomposition, d13C, and the ‘‘lignin paradox’’. Can J Soil Sci 2006, 86, 235–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, I.; Mahieu, N.; Cadisch, G. Carbon isotopic fractionation during decomposition of plants materials of different quality. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 2003, 17, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, M.; Fear, J.; Cadisch, G. Isotopic δ13C Fractionation during plant residue decomposition and its implications for soil organic matter studies. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1999, 13, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; Booltink, H.G.W.; Breymeyer, A.; Ewertsson, A.; Gallardo, A.; Holm, B.; Johansson, M.-B.; Koivuoja, S.; Meentemeyer, V.; Nyman, P.; Olofsson, J.; Pettersson, A.-S.; Reurslag, A.; Staaf, H.; Staaf, I.; Uba, L. Data on needle litter decomposition and soil climate as well as site characteristics for some coniferous forest sites. 2nd ed. Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Department of Ecology and Environmental Research. Section 1 Data on site characteristics. Report No 41. 1991.

- Berg, B.; McClaugherty, C.; Johansson, M.B. Chemical changes in decomposing plant litter can be systemized with respect to the litter’s initial chemical composition. Reports from the departments in Forest Ecology and Forest Soils. Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, 85. Report 74., 1997.

- Berg, B.; Berg, M.P.; Bottner, P.; Box, E.; Breymeyer, A.; Calvo de Anta, R.; Couteaux, M.; Gallardo, A.; Escudero, A.; Kratz, W.; Madeira, M.; Mälkönen, E.; Meentemeyer, V.; Munoz, F.; Piussi, P.; Remacle, J.; Virzo De Santo, A. Litter mass loss rates in pine forests of Europe and eastern United States: Some relationships with climate and litter quality. Biogeochemistry 1993, 20, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; Booltink, H.G.W.; Breymeyer, A.; Ewertsson, A.; Gallardo, A.; Holm, B.; Johansson, M.-B.; Koivuoja, S.; Meentemeyer, V.; Nyman, P.; Olofsson, J.; Pettersson, A.-S.; Reurslag, A.; Staaf, H.; Staaf, I.; Uba, L. Data on needle litter decomposition and soil climate as well as site characteristics for some coniferous forest sites. 2nd ed. Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Section 2. Data on needle litter decomposition. Department of Ecology and Environmental Research. Report No 42. REP 43, 1991.

- Olson, J.S. Energy storage and the balance of producers and decomposers in ecological systems. Ecology 1963, 44, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, R.K.; Lang, G.E. (1982) A critique of the analytical methods used in examining decomposition data obtained from litter bags. Ecology 1982, 63, 1636–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; Ekbohm, G. Littermass–loss rates and decomposition patterns in some needle and leaf litter types. Long–term decomposition in a Scots pine forest. VII. Can. J. Bot. 1991, 69, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, B. Stable isotope ecology. Springer:New York, NY, 2006.

- Fernandez, I.; Cadisch, G. Discrimination against 13C during degradation of simple and complex substrates by two white rot fungi. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 2003, 17, 2614–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Macko, S.A.; Shugart, H.H. Insights into nitrogen and carbon dynamics of ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungi from isotopic evidence. Oecologia 1999, 118, 353–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boström, B.; Comstedt, D.; Ekblad, A. Isotope fractionation and 13 C enrichment in soil profiles during the decomposition of soil organic matter. Oecologia, 2007, 153, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, N.E.A.L.; Leu, A.; Olsen, J.; Kwong, E.; Des Marais, D. Carbon isotopic fractionation in heterotrophic microbial metabolism. App. Env. Microbiol. 1985, 50, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, M.; Kuzyakov, Y. 13C fractionation at the root–microorganisms–soil interface: a review and outlook for partitioning studies. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1372–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, B.; Mariotti, A.; Morel, J.L. Use of 13C variations at natural abundance for studying the biodegradation of root mucilage, roots and glucose in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem 1992, 24, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, X. Does short–term litter input manipulation affect soil respiration and its carbon–isotopic signature in a coniferous forest ecosystem of central China? Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 113, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šantrůčková, H.; Bird, M.I.; Lloyd, J. Microbial processes and carbon-isotope fractionation in tropical and temperate grassland soils. Funct. Ecol 2000, 14, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazza, L.; Iacumin, P. Seasonal variation in carbon isotopic composition of bog plant litter during 3 years of field decomposition. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2009, 46, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, R.; Fogel, M.L.; Sprague, E.K.; Hodson, R.E. Depletion of 13C in lignin and its implications for stable carbon isotope studies. Nature 1987, 329, 708–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.J.; Huang, W.; Timokhin, V.I.; Hammel, K.E. Lignin lags, leads, or limits the decomposition of litter and soil organic carbon. Ecology 2020, 101, e3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, B.; Staaf, H. Decomposition rate and chemical changes of Scots pine needle litter. II. Influence of chemical composition. Ecol. Bullet. 1980, 373–390. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Macko, S.A.; Williams, M. Correlations between foliar δ15N and nitrogen concentrations may indicate plantmycorrhizal interactions. Oecologia 2000, 122, 273–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, M.; Frey, S.D.; Curtis, P.S. Nitrogen additions and litter decomposition: A meta–analysis. Ecology 2005, 86, 3252–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, J.M.; Treseder, K.K. Interactions among lignin, cellulose, and nitrogen drive litter chemistry–decay relationships. Ecology 2012, 93, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Hungate, B.A.; Cao, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, R. A keystone microbial enzyme for nitrogen control of soil carbon storage. Sci. Adv. 2018; 4, eaaq1689. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.; Söderström, B. Fungal biomass and nitrogen in decomposing Scots pine needle litter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1979, 11, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, R.J.K.; Palm, C.A.; Cuevas, E.; Gunatilleke, I.U.N.; Brossard, M. The synchronization of nutrient mineralization and plant nutrient demand. In, Woomer PL, Swift MJ (eds.) The biological management of tropical soil fertility. John Wiley and Sons, UK, 1994; pp 81–116.

- Kramer, M.G.; Sollins, P.; Sletten, R.S.; Swart, P.K. N isotope fractionation and measures of organic matter alteration during decomposition. Ecology 2003, 84, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogberg, M.N.; Hogberg, P.; Myrold, D.D. Is microbial community composition in boreal forest soils determined by pH, C–to–N ratio, the trees, or all three? Oecologia 2007, 150, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NSL | SPL | |

| ksyr-1 | ||

| AML | 0.22 | 0.32 |

| C | 0.002 | -0.031 |

| N | -0.21 | -0.25 |

| AUR | -0.12 | -0.21 |

| δ13C | 0.003 | -0.007 |

| δ15N | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Δ(‰) | ||

| Δ13C (‰) | 0.33 | -0.74 |

| Δ15N (‰) | -1.74 | -1.99 |

| AML | C | N | AUR | C/N | AUR/N | |

| ksNSL | -0.49 | -0.27 | -0.54 | -0.48 | 0.67* | 0.72* |

| ksSPL | -0.89* | -0.18 | -0.90* | -0.91* | 0.94* | 0.92* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).