1. Introduction

The understanding of autism has significantly evolved since the early 20th century, marked by contributions from pioneers such as Grunya Efimovna Sukhareva, Leo Kanner, and Eugen Bleuler [

1]. Grunya Efimovna Sukhareva, a Soviet child psychiatrist, provided one of the earliest detailed descriptions of autism spectrum disorder in 1925. Her work identified behaviors in children that closely align with modern diagnostic criteria, including social withdrawal and sensory abnormalities, offering a comprehensive view that included both behavioral and physical health. Despite the groundbreaking nature of her observations, her contributions were overlooked mainly due to the linguistic, political, and gender barriers of her time. Concurrently, the term autism was first introduced by Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1911 during a congress in England, where he described it as a subset of symptoms observed in schizophrenia, characterizing patients who were withdrawn and self-absorbed. This initial use of the term laid the groundwork for future exploration and understanding of autism as a distinct condition. In the current medical landscape, autism is primarily viewed as a neurodevelopmental disorder with a strong genetic basis, yet it remains a complex condition influenced by various environmental factors [

2]. Despite advances in research, the diagnostic process often emphasizes psychiatric assessments [

3], potentially leading to superficial evaluations that overlook critical comorbidities such as gastrointestinal disturbances, metabolic dysfunctions, and immune irregularities. These underlying conditions can mimic or exacerbate core autistic symptoms, complicating both diagnosis and treatment. As our understanding of autism deepens, there is a growing need for a comprehensive and integrative diagnostic approach that considers both differential and complementary diagnoses. This approach acknowledges the intricate interplay of medical and psychiatric symptoms and seeks to improve diagnostic accuracy and intervention effectiveness, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for individuals with autism.

The prevalence of ASD is increasing, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates from 2023 indicating that it affects 1 in 36 children in the United States. This underscores the pressing need for advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [

3]. A significant concern in the management of autism is the prevalence of polypharmacy, wherein individuals are often prescribed multiple medications to manage a wide array of associated symptoms and comorbidities. Studies have indicated that individuals with ASD are much more likely to receive prescriptions from numerous medication classes. This not only complicates clinical management but also increases the risk of adverse drug interactions and side effects [

5]. Furthermore, the life expectancy of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder is significantly affected. Recent research indicates that the average life expectancy of those with ASD can be up to 16 years shorter than that of the general population, mainly because of a combination of health comorbidities, such as epilepsy and mental health conditions, and external factors, including inadequate healthcare responses to their unique needs. The necessity for personalized approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of autism is becoming increasingly apparent. These approaches must account for the diverse clinical profiles and intricate interplay of the genetic, neurological, and environmental factors that characterize ASD. By tailoring strategies to individuals, it is possible to significantly enhance the quality of life and health outcomes of those affected by this complex condition [

6]. This article advocates for such a paradigm shift, building on the pioneering insights of early researchers such as Sukhareva, to foster a more nuanced and integrative understanding of autism, aiming to develop a comprehensive stratification model for ASD based on clinical profiles utilizing precision medicine techniques to identify and categorize ASD into ten distinct profiles. These profiles are intended to guide personalized therapeutic strategies and improve the overall health outcomes in individuals with ASD.

2. Methods

This article introduces a clinical stratification model for Autism Spectrum Disorder, proposing distinct clinical profiles based on prevalent comorbidities and underlying biological mechanisms. The model draws on existing research investigating various mechanisms, metabolic pathways, and pathophysiological processes related to autism, including mitochondrial, immunological, inflammatory, gastrointestinal, infectious, metabolic, and endocrine factors. While individual studies provide insights into these areas, this study integrates these perspectives into a cohesive framework to offer a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment.

A synthesis informs the model of peer-reviewed articles and meta-analyses exploring these factors' role in autism. Each profile is characterized by specific symptomatology and associated biological mechanisms, facilitating a more tailored approach to diagnosis and intervention. This approach considers how the intersection of clinical comorbidities can affect the presentation of ASD symptoms, supporting a more integrated diagnostic strategy.

The data for this model were gathered from various clinical settings, encompassing comprehensive clinical evaluations, patient histories, and laboratory tests. We utilized analytical tools to identify patterns and categorize clinical profiles, relying upon medical records and case studies to establish a robust foundation for the model.

This model's objective is to improve the accuracy of the diagnostic process by integrating conventional diagnostic criteria with state-of-the-art biomarkers and behavioral assessments. The proposed stratification model seeks to address the complexity of autism by acknowledging the intricate interplay between medical and psychiatric symptoms. This article advocates for a shift towards integrated diagnostic strategies that improve the accuracy of diagnoses and the effectiveness of interventions, ultimately enhancing the quality of care for individuals with autism.

Treatment response is a critical factor in refining stratification. Initial treatment strategies focused on addressing gastrointestinal, metabolic, and nutritional issues. Subsequent interventions have targeted food allergies, endocrine imbalances, infectious diseases, autoimmune conditions, and chronic inflammation.

The validity of the proposed model was evaluated against established clinical guidelines and current best practices for autism. This involved comparing the outcomes derived from traditional diagnostic methods with those suggested by precision medicine [

7]. This discussion is based on scientific evidence and aims to provide a clear rationale for adopting a personalized approach to ASD management.

This structured methodology allows treatment plans to be tailored to each patient’s needs based on their unique clinical profiles. This model aims to improve therapeutic outcomes by addressing the particular challenges and requirements inherent to each ASD subtype.

3. The Personalized and Integrated Approach to ASD

According to recent data from the CDC, Autism Spectrum Disorder affects approximately 2.8% of the population in the United States [

2]. This highlights the importance of a personalized and comprehensive approach to managing autism, including medical, psychological, educational, and therapeutic interventions tailored to each patient's needs. Precision medicine is crucial for understanding neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism. It thoroughly evaluates medical history, physical examination, and biomarkers to identify unique clinical profiles [

8]. A critical aspect of this methodology is the systematic and comprehensive assessment of simple and complex comorbidities to identify the root causes of the presenting symptoms.

Implementing this approach in diagnosing and managing comorbidities among individuals with ASD, especially within the framework of ten clinical profiles, offers substantial advantages. These include enhanced symptom management, increased effectiveness of treatments and behavioral therapies, disease prevention, and potential reductions in healthcare costs and medication usage. This process is essential for gathering extensive phenotypic data and biomarkers, including epigenetic markers, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and neurobehavioral metrics. Such detailed profiling facilitates the differentiation of distinct clinical profiles, leading to improved prognoses and, ultimately, a significant enhancement in the quality of life of these individuals across the short-, medium-, and long-term [

9].

4. Clinical Profiles in ASD

Genetics are crucial in the development of ASD, but its phenotypic expression varies due to interactions with other factors [

10]. Precision medicine integrates genomic insights into biological processes and environmental factors. This approach facilitates the development of personalized therapies tailored to individual patient-specific needs while exploring a variety of triggers to understand the root cause of symptoms, including internal and external factors. For example, metabolic disruptions can lead to various symptoms, whereas genetic variations can affect neurotransmitter synthesis and mitochondrial functions [

11]. Additionally, the composition of the gut microbiome significantly influences the microbiome-gut-brain axis, which can cause inflammation, autoimmune reactions, or pain [

12,

13,

14].

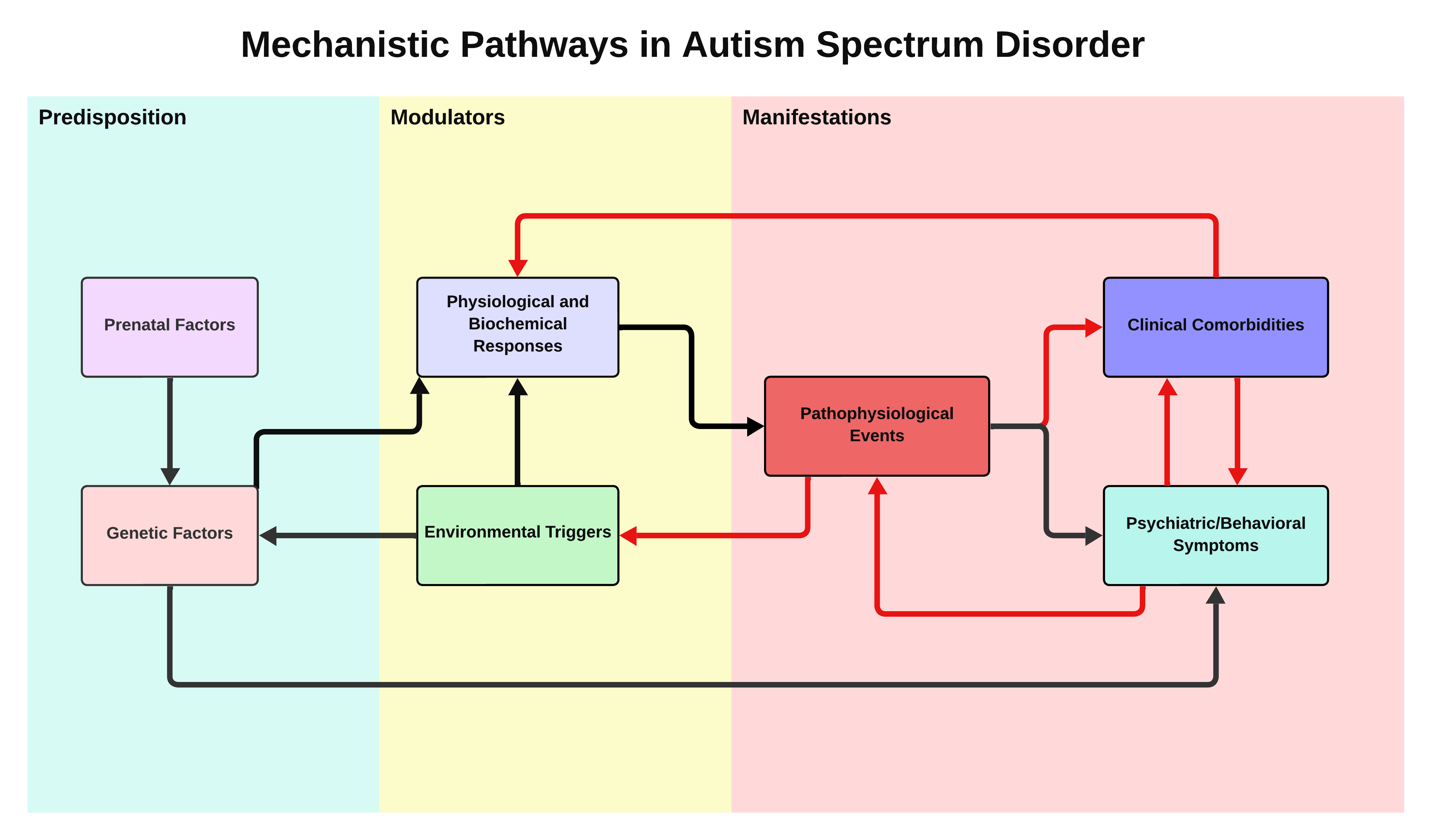

Individuals with autism typically exhibit unique symptoms and comorbidities that are frequently exacerbated by external factors such as infections or diet, which often lead to metabolic disruptions. These disruptions can trigger immune dysregulation, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Approximately 70% of individuals with autism have some form of metabolic dysfunction, whereas almost 90% face gastrointestinal difficulties. However, these symptoms are often misinterpreted as behavioral problems, overlooking the potential origins [

15,

16,

17,

18]. The coexistence of psychiatric signs and clinical comorbidities offers critical insights for clinicians that can be obtained through comprehensive physical examinations, detailed medical histories, and laboratory tests. These insights are instrumental in identifying distinct clinical profiles within the autism spectrum and facilitating the development of customized treatment plans and interventions for effective and targeted care [

19].

Ten clinical profiles have been meticulously developed to assist in diagnosing and treating various conditions in ASD as follows:. (1) Syndromic (2) Gastrointestinal (3) Metabolic (4) Mitochondrial (5) Endocrine (6) Infectious (7) Bioaccumulative (8) Immunological (9) Inflammatory (10) Neurological

It is vital to acknowledge that the presentation of these profiles may vary. A particular profile may be more evident during initial evaluations, whereas further assessments may reveal additional associated profiles. This dynamic and evolving process is crucial for accurately understanding each individual’s unique factors and allowing for tailored treatment strategies. Initially, patients may present with multiple profiles due to untreated comorbidities. The persistent presentation of symptoms helps clinicians to stratify and refine clinical profiles over time. Identifying and differentiating particular clinical profiles and subtypes of autism is achieved using a multi-tiered approach that includes observing characteristic signs and symptoms, following progression from primary to complex treatment protocols, and utilizing targeted laboratory examinations. Each profile presents unique features, and understanding these nuances is pivotal for tailoring interventions according to individual needs [

20].

4.1. Syndromic Profile

The Syndromic Profile in ASD is seen in individuals with genetic syndromes such as Down Syndrome, Fragile X Syndrome, and Rett Syndrome [

21,

22,

23]. A critical aspect of this profile is the potential for delayed or overlooked diagnosis of autism. The symptoms and challenges associated with genetic syndromes can overshadow the behavioral and developmental signs of autism. Therefore, autism, as a co-occurring neurodevelopmental condition, may not be promptly recognized or adequately addressed [

24]. This trend highlights a significant diagnostic oversight in which the primary genetic syndrome manifestations might be exclusively attributed to the syndrome, neglecting the possibility of autism [

25]. Therefore, healthcare professionals must be vigilant about the signs of autism in individuals with genetic syndromes and not attribute all symptoms and behaviors solely to the primary syndrome.

4.2. Gastrointestinal Profile

The gastrointestinal profile is a significant aspect of the autism spectrum. It is particularly prevalent in those who have not received nutritional interventions for allergies, intolerance, or food sensitivities that impact the microbiota-intestine-brain axis [

6,

12,

13,

18]. Notably, a significant proportion of individuals with autism experience gastrointestinal symptoms. These symptoms are often characterized by chronic conditions, such as diarrhea, which is prevalent in up to 45% of individuals with ASD, and constipation, which is reported in approximately 30-45% of cases. Additional frequently observed symptoms include abdominal distension, skin rashes, and persistent diaper rashes [

13,

26,

27]. Furthermore, conditions such as Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) may contribute to this profile, causing discomfort and affecting the overall well-being of affected individuals [

28].

Addressing the Gastrointestinal Profile requires a comprehensive approach, starting with a thorough assessment to identify the underlying causes. This includes laboratory tests for nutritional deficiency, immune dysfunction, and gastrointestinal inflammation [

29,

30]. Personalized treatment plans for this profile often involve dietary modifications and supplements.

It is crucial to recognize that gastrointestinal symptoms in autism, such as chronic diarrhea or constipation, may be misinterpreted as purely behavioral issues. Effective management requires a deep understanding of each patient’s medical history, including gastrointestinal symptoms, dietary habits, and responses to prior treatment [

31].

4.3. Metabolic Profile

A complex interplay between genetic and non-genetic factors shapes the metabolic profiles of individuals with autism [

32]. Genetic variants such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can significantly affect critical metabolic pathways, including the one-carbon metabolism pathway. This pathway is integral to various biological functions and illustrates the influence of genetic factors on metabolism.

In addition to genetic influences, non-genetic and epigenetic factors play a substantial role in shaping metabolic profiles, including enteropathies and deficiencies in essential nutrients such as zinc, iron, and calcium [

33,

34]. The combined effects of these genetic and non-genetic elements contribute to various metabolic challenges, leading to increased oxidative stress, diminished energy production, and altered metabolic pathways [

35].

Moreover, the interaction between nutrition, environmental factors, and genetic predispositions is pivotal in determining the metabolic function in individuals with autism. This dynamic underscores the importance of personalized nutritional and environmental management approaches for metabolic health.

4.4. Mitochondrial Profile

Individuals with autism often experience mitochondrial dysfunction, which can manifest in various ways, such as facial hypotonia, speech delay, suspected apraxia of speech, epilepsy, and cognitive challenges. Mitochondrial dysfunction can be linked to inborn errors of metabolism, such as MCAD gene polymorphisms, which are crucial for β-oxidation of medium-chain fatty acids and mitochondrial energy production [

36,

37]. Deficiencies in essential nutrients, such as the vitamin B complex, can also lead to mitochondrial dysfunction. Patients with mitochondrial dysfunction may also exhibit increased allergy and atopic conditions. Environmental allergens and toxins can exacerbate this dysfunction, leading to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and impairment of the electron transport chain, causing mitochondrial damage, mast cell degranulation, and triggering inflammatory and allergic responses [

38].

A comprehensive approach encompassing genetic and environmental factors is essential to address mitochondrial dysfunction in autism. Nutritional support is crucial for optimizing mitochondrial function, highlighting the importance of a tailored dietary strategy for managing this aspect of autism [

39].

4.5. Endocrine Profile

Individuals with ASD may exhibit deficiencies in hormone production, particularly in steroids and thyroid hormones, which can manifest as endocrine profiles [

40,

41,

42]. This profile is characterized by symptoms of hormonal imbalances that may present as either insufficient or excessive hormone production.

A key concern within this profile is the disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-thyroid (HPA-T) axis, which can significantly affect various bodily systems. Proper regulation of this axis is critical, as imbalances may precipitate more severe psychiatric disorders and chronic illnesses [

43,

44,

45]. The initial presentation of this profile often involves elevated cortisol levels that may lead to decreased cortisol levels over time. This dysregulation suggests either hyporeactivity or hyperreactivity of the HPA-T axis [

46,

47,

48].

Assessing cortisol production is essential to delineate the endocrine profile and ensure that the adrenal glands are sufficiently robust to support diverse treatments, including those for infections. Individuals with this endocrine profile commonly experience speech delay, significant sensory dysfunction, and hypotonia [

45,

49].

Individuals with ASD and an identified endocrine profile are commonly diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [

46,

50]. Treatment strategies typically involve eliminating endocrine disruptors, managing inflammation, and supporting adrenal and thyroid functions, as required.

4.6. Bioaccumulative Profile

The phenotypic expression of autism is influenced by the complex interplay between environmental factors, such as exposure to toxins and pesticides, and genetic predispositions [

16,

51,

52]. Various single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), including MTHFR, CBS, and SUOX, affect detoxification processes in the body, making them genetic factors that influence this profile [

53]. These genetic variations significantly affect how the body handles and eliminates the toxins. Individuals with this profile often show clinical signs of systemic intoxication, such as dark circles under the eyes, edema, dermatitis, chronic fatigue, and neurological symptoms. Recognizing and addressing these signs is crucial to effectively managing their conditions [

54,

55,

56].

Effective management of the Bioaccumulative Profile involves reducing toxin exposure, utilizing targeted detoxification therapies, and a diet rich in antioxidants, essential nutrients, and phytochemicals to support detoxification [

57,

58]. Understanding an individual’s specific genetic makeup, particularly in genes related to detoxification, is vital for developing personalized therapeutic approaches to enhance detoxification efficiency and alleviate the adverse effects of bioaccumulation [

59].

4.7. Infectious Profile

Psychiatric and neurological disorders, including autism, are often intricately linked to the immune and inflammatory responses to various infections [

19,

28]. Understanding the infectious profile is essential for comprehending these conditions as it offers insights into the potential underlying causes and guides appropriate treatment strategies. Analyzing the immune system response and cytokine profiles is crucial for clinicians to understand the role of infectious processes in the development of symptoms observed in autism and other psychiatric disorders.

It is essential to recognize the potential overlap and confusion in symptom presentation between conditions, such as Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS), Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS), and autism [

60]. These conditions can be challenging to diagnose, especially in children aged 3-17 years, owing to the similarities in their presentation with autism, which leads to diagnostic complexities. An overactive immune response to infection can trigger autoimmune encephalitis and cause brain inflammation and neuropsychiatric symptoms that may resemble or exacerbate autism symptoms [

61,

62,

63].

Furthermore, it is essential to acknowledge that anxiety in individuals with autism may be associated with various viral infections [

64]. These infections can lead to neuroinflammation and contribute to neuropsychiatric symptoms. The emergence of COVID-19 and the associated neuroinflammatory responses, including in children with autism, underscores the need for pediatricians to be particularly vigilant [

65,

66,

67]. This vigilance is crucial for detecting neurodevelopmental regression or other changes that may indicate an infectious or an autoimmune response.

Individuals with autism may experience concurrent infections or autoimmune encephalitis of infectious origin that may affect their clinical presentation. Therefore, a thorough and detailed investigation is vital for the diagnosis and treatment of autism, recognizing that individuals with autism can experience a wide range of health issues, including those related to infections [

68].

4.8. Immunological Profile

The Immunological Profile presents significant challenges owing to its complexity and severity, often resulting in poor prognosis. This profile is influenced by various immunological triggers, including infections, exposure to toxic agents, and comorbidities, all contributing to management difficulties. One of the critical challenges in this profile is the significant overlap and mimicry of symptoms with conditions such as viral encephalitis, leading to potential diagnostic errors. Patients with immunological profiles may exhibit a range of symptoms and conditions, such as Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD), selective eating, and multiple allergies. Owing to their severity, these patients often require moderate to high levels of support and respond well to treatments such as antibiotics, corticosteroids, or immunomodulatory drugs [

60,

68,

69].

Additionally, a history of autoimmune diseases, including upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) and atopic dermatitis, is common in these patients. Significantly, conditions such as Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) and Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS) are strongly associated with immunological profiles [

70]. Both PANS and PANDAS are characterized by sudden-onset neuropsychiatric symptoms following an infection, often leading to significant behavioral changes and exacerbation of autism-related symptoms. Recognizing and addressing these conditions is crucial for managing the Immunological Profile, as they demonstrate the profound impact of immunological factors on neuropsychiatric presentation in autism. Managing the immunological profile requires a comprehensive approach that focuses on the specific immunological needs of each individual and tailors treatment strategies to effectively address a broad spectrum of symptoms and their underlying triggers [

71].

4.9. Inflammatory Profile

The Inflammatory Profile is characterized by chronic inflammation, evident through elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). This profile is frequently observed in patients with gastrointestinal tract disorders and is initially observed in a significant proportion of individuals with autism spectrum disorders [

72]. Gastrointestinal symptoms often serve as early indicators of an inflammatory profile originating from gut inflammation, which is common in these patients. The primary sources of inflammation are intestinal- and diet-related factors [

73]. However, the defining characteristic of the inflammatory profile is persistent inflammation, even after addressing various underlying issues, including intestinal dysfunction, endocrine abnormalities, subclinical infections, and autoimmune diseases.

Despite comprehensive treatment efforts, some patients continue to exhibit clinical and laboratory signs of inflammation, indicating the presence of chronic inflammatory disease. This persistent inflammation suggests an ongoing role of the inflammasome, a multiprotein complex involved in chronic inflammatory conditions. Identifying specific Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) that contribute to the pro-inflammatory state is crucial for understanding individual variations in inflammatory responses [

74]. Notably, SNPs, such as those in the MTHFR and TNF genes, specifically TNF-α -308G>A, have been extensively studied for their roles in inflammatory processes [

72].

Inflammation is a common mechanism in several diseases. It's important to note that even after treating various clinical conditions and eliminating all possible inflammatory triggers, inflammation and the inflammatory profile persist. This underscores the need for particular and targeted strategies for managing chronic inflammation, which appears to be intrinsic to the inflammatory profile in ASD.

4.10. Neurological Profile

The neurological profile of individuals with autism is often identified early in treatment or may have been previously diagnosed with a condition related to the central nervous system (CNS). This profile encompasses conditions such as epilepsy, congenital malformations, and syndromes that result in seizure disorders, including Landau-Kleffner syndrome [

75,

76]. In some instances, a neurological profile may develop because of a lack of diagnosis and subsequent treatment of chronic neuroinflammation, leading to worsening of the overall condition.

Recent studies have highlighted the critical role of amino acid metabolism, particularly tryptophan metabolism, in the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric disorders [

79]. Dysregulation of the tryptophan metabolic pathway has been implicated in conditions such as schizophrenia and could similarly influence the neurological profile of autism [

80]. This suggests that metabolic interventions targeting amino acid imbalances may be a potential avenue for managing treatment-resistant neurological symptoms in ASD.

An, and that integrative approach is vital for the understanding and management of neurological profiles. For instance, individuals with severe allergies may experience food-reactive epilepsy, or food allergies can lead to adenoid hypertrophy, causing hypoxia and nocturnal epilepsy [

77,

78]. Identifying and addressing these underlying factors is crucial, especially for treatment-resistant neurological symptoms, and it is essential to recognize that the CNS interacts with all profiles within the autism spectrum. While the Neurological Profile may predominantly display neurological characteristics and symptoms, these can be influenced by various factors, including gut-related disorders, infections, intoxication, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation.

5. Discussion

Autism spectrum disorder is a complex disorder that presents significant challenges in terms of diagnosis and treatment owing to its wide range of symptoms and comorbidities. Despite substantial progress in understanding ASD and its associated conditions, there is a need for extensive exploration, especially in understanding the variation in symptom presentation among individuals with autism, which complicates the diagnostic process. The current diagnostic criteria for ASD do not fully capture its complexity and heterogeneity. This gap presents a challenge for developing personalized diagnostic tools and treatments. Focusing on preventive medicine, especially when it comes to comorbidities, is crucial for enhancing the quality of life of individuals with autism. Many symptoms that exacerbate the challenges faced by individuals with autism are either direct manifestations of untreated clinical comorbidities or worsened by them [

20,

28]. Moreover, symptoms arising from these comorbidities can often be misinterpreted by professionals as a core aspect of autism, leading to an inaccurate diagnosis. Neglecting the treatment of these comorbidities can have negative consequences, including worsening of the patient’s required support, prognosis, and overall quality of life [

80].

Psychiatry can be challenging due to the absence of conventional laboratory findings for the identification of certain disorders. This lack of recognition is partly due to difficulties obtaining meaningful medical histories and conducting physical tests, particularly for non-verbal individuals or those whose behaviors may interfere with assessments. Hence, it is crucial to accurately subtype and genotype individuals with ASD to enhance treatment and add various psychiatric and clinical comorbidities [

41].

Precision medicine has the potential to refine treatments for psychiatric symptoms in ASD patients. Identifying clinical profiles can provide a more accurate assessment of individuals with autism and, consequently, better treatment options. It also helps monitor and predict symptoms' progression and potential complications and identify future treatment possibilities [

8]. However, further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of precision medicine in treating psychiatric symptoms, its potential risks and long-term effects, and the potential of precision medicine for treating patients with ASD.

This study highlights the significance of a personalized and integrated approach to managing autism, emphasizing the integration of the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria based on behavioral observations. Although the DSM-5 provides a standardized framework for ASD diagnosis, the heterogeneity of autism and the presence of both clinical and psychiatric comorbidities often complicate the identification of distinct clinical profiles. By incorporating various clinical profiles, this approach aims to achieve a more comprehensive understanding and diagnosis of autism, addressing its diverse and complex nature more effectively. This approach should integrate various medical, psychological, educational, and therapeutic interventions tailored to individual needs. Considering the complexity of neurodiversity, it is crucial to correlate the core signs and symptoms of autism with potential clinical comorbidities [

20]. This ensures that comorbidities causing or exacerbating symptoms are identified and treated appropriately rather than being mistaken for autism symptoms alone. Embracing an integrative perspective encompassing genetic factors and a broad spectrum of associated conditions will enable professionals to develop precise and effective interventions. This approach improves patient outcomes and the quality of life of individuals with autism and their families.

Advancing our understanding of ASD involves identifying distinct clinical profiles and utilizing epigenetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic markers and neurobehavioral measures. This strategy aims for more accurate diagnoses and treatments, potentially reducing the incidence of chronic diseases, improving prognoses, achieving cost efficiency, and enhancing the effectiveness of behavioral therapies. Such holistic approaches signify a significant paradigm shift in autism care, promising a future with better health outcomes and opportunities for individuals with ASD.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The novel stratification model for ASD was preliminarily validated in a controlled clinical environment, highlighting areas needing further investigation owing to inherent limitations.

Empirical validation of the model was confined to a specific patient cohort within a clinical setting, providing promising preliminary results. However, these findings may not adequately capture the full diversity of ASD as observed in broader clinical practice. The development of the model relied heavily on existing literature, which, while extensive, may carry inherent biases or limitations that could affect its comprehensiveness and applicability in different clinical contexts. Furthermore, owing to the complex and variable nature of ASD, the model, despite its robust framework, might only partially capture the nuances of the individual cases. This reflects the inherent challenge of creating diagnostic models universally applicable to a broad spectrum of ASD manifestations [

81,

82].

Several directions for future research are evident. To further validate the model's effectiveness, it is necessary to conduct broader empirical studies that extend beyond the initial clinical settings and include more diverse patient cohorts across different environments. This expansion helps establish the robustness and generalizability of the model. Additionally, there is a need to explore how the model can be seamlessly integrated into routine clinical practice. Developing practical implementation tools and guidelines would facilitate their use by a broader range of healthcare professionals, thus enhancing the model’s accessibility and utility.

We planned a series of follow-up studies to delve more deeply into the clinical profiles introduced in this preliminary study. Future studies should provide a more detailed characterization of each profile to help clinicians integrate these findings into routine practice. This approach includes laboratory investigations and identifying clinical symptoms to improve the quality of life and clinical stratification of patients with autism. The goal was to offer more tailored and effective treatments by refining our understanding of each profile and the associated comorbidities.

Future research can enhance the effectiveness of the stratification model in diagnosing and treating ASD by validating and refining the model, exploring suggested research directions, and addressing limitations. Ultimately, this results in improved patient outcomes.

7. Conclusions

This research presents a stratification model for Autism Spectrum Disorder, aiming to improve the precision of diagnosis and the effectiveness of treatment. By gaining a detailed understanding of the diverse manifestations of ASD, the model challenges traditional diagnostic approaches. Its implementation in clinical practice has the potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy and treatment outcomes by tailoring interventions to each individual's unique needs and characteristics. Additionally, the model addresses comorbid conditions associated with ASD, improving overall patient care and management strategies. The integration of personalized medicine into standard care could revolutionize the management of Autism Spectrum Disorder, offering more effective healthcare solutions and potential insights into the pathophysiology of ASD.

Author Contributions

Sample: Somit Jain: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing (equal). Shobhit Agrawal: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing (equal). Eshaan Mohapatra: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing (equal). Kathiravan Srinivasan: Methodology, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing.

Funding

This research received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACTH |

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone |

| ADHD |

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ASD |

Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CNS |

Central Nervous System |

| DMDD |

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| GERD |

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| HPA |

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal |

| HPA-T |

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal-Thyroid |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| MCAD |

Medium-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase |

| OCD |

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

| PANDAS |

Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections |

| PANS |

Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic Acid |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SIBO |

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth |

| SNP |

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| URTI |

Upper Respiratory Tract Infection |

References

- Simmonds, Charlotte (2019). G. E. Sukhareva's place in the history of autism research: Context, reception, translation. Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington. Thesis.

- C. Andrés et al., "The importance of genetics in an advanced integrative model of autism spectrum dis-order," Journal of Translational Genetics and Genomics, 2022.

- Association, A.P. "Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders," 5th ed., text rev. Ed. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Maenner, M.J. , Warren, Z.; Williams, A.R.; Amoakohene, E.; Bakian, A.V.; Bilder, D.A.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR. Surveill. Summ. 2023, 72, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, C.; Hewitt, K.; McMorris, C.A. Psychotropic Polypharmacy Among Children and Youth with Autism: A Systematic Review. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 31, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaureguiberry, M.S.; Venturino, A. Nutritional and environmental contributions to autism spectrum disorders: Focus on nutrigenomics as complementary therapy. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2022, 92, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, R.E. A Personalized Multidisciplinary Approach to Evaluating and Treating Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.L.; Loyacono, N. Rationale of an Advanced Integrative Approach Applied to Autism Spectrum Disorder: Review, Discussion and Proposal. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. D. Leann et al., "Mortality in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: Predictors over a 20-year period," Autism: the International Journal of Research and Practice, vol. 23, pp. 1732 - 1739, 2019.

- B. Dan et al., "Association of Genetic and Environmental Factors With Autism in a 5-Country Cohort," JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 76, pp. 1035 - 1043, 2019.

- LaSalle, J.M. Epigenomic signatures reveal mechanistic clues and predictive markers for autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1890–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Chiara et al., "The Gut-Brain-Immune Axis in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A State-of-Art Report," Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2022.

- Davies, C.; Mishra, D.; Eshraghi, R.S.; Mittal, J.; Sinha, R.; Bulut, E.; Mittal, R.; Eshraghi, A.A. Altering the gut microbiome to potentially modulate behavioral manifestations in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. Shunya et al., "The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea, and functional constipation: An open-label observa-tional study," Journal of Affective Disorders, 2018.

- De Santis, B.; Raggi, M.E.; Moretti, G.; Facchiano, F.; Mezzelani, A.; Villa, L.; Bonfanti, A.; Campioni, A.; Rossi, S.; Camposeo, S.; et al. Study on the Association among Mycotoxins and other Variables in Children with Autism. Toxins 2017, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modabbernia, A.; Velthorst, E.; Reichenberg, A. Environmental risk factors for autism: an evidence-based review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Mol. Autism 2017, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, J.R. The plausibility of maternal toxicant exposure and nutritional status as contributing factors to the risk of autism spectrum disorders. Nutr. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krigsman, A.; Walker, S. J. "Gastrointestinal disease in children with autism spectrum disorders: Eti-ology or consequence," World J Psychiatry, vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 605-618.

- L. B. Margaret, "Medical comorbidities in autism: challenges to diagnosis and treatment," Neurothera-peutics: the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, vol. 7, pp. 320 - 7, 2010.

- T. Charlotte et al., "Characterizing the Interplay Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Comorbid Medical Conditions: An Integrative Review," Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 9, pp. 751 -, 2019.

- Bozhilova, N.; Welham, A.; Adams, D.; Bissell, S.; Bruining, H.; Crawford, H.; Eden, K.; Nelson, L.; Oliver, C.; Powis, L.; et al. Profiles of autism characteristics in thirteen genetic syndromes: a machine learning approach. Mol. Autism 2023, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenner, L.; Richards, C.; Howard, R.; Moss, J. Heterogeneity of Autism Characteristics in Genetic Syndromes: Key Considerations for Assessment and Support. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2023, 10, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Iram et al., "The Role of Genetic Testing Among Autistic Individuals," Pediatrics, vol. 149, 2022.

- Genovese, A.; Butler, M.G. The Autism Spectrum: Behavioral, Psychiatric and Genetic Associations. Genes 2023, 14, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Natasha et al., "The role of new genetic technology in investigating autism and developmental delay," Medicine and health, Rhode Island, vol. 94, pp. 131, 134 - 7, 2011.

- K. Jenni et al., "Systematic review: Autism spectrum disorder and the gut microbiota," Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 2023.

- Holingue, C.; Pfeiffer, D.; Ludwig, N.N.; Reetzke, R.; Hong, J.S.; Kalb, L.G.; Landa, R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms among autistic individuals, with and without co-occurring intellectual disability. Autism Res. 2023, 16, 1609–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Beltagi, M. Autism medical comorbidities. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbjornsdottir, B.; Snorradottir, H.; Andresdottir, E.; Fasano, A.; Lauth, B.; Gudmundsson, L.S.; Gottfredsson, M.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Birgisdottir, B.E. Zonulin-Dependent Intestinal Permeability in Children Diagnosed with Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Xinrui et al., "Gastrointestinal Issues in Infants and Children with Autism and Developmental Delays," Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 2017.

- Senarathne, U.D.; Indika, N.-L.R.; Jezela-Stanek, A.; Ciara, E.; Frye, R.E.; Chen, C.; Stepien, K.M. Biochemical, Genetic and Clinical Diagnostic Approaches to Autism-Associated Inherited Metabolic Disorders. Genes 2023, 14, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hana, A.; et al. "Nutritional Status of Pre-school Children and Determinant Factors of Autism: A Case-Control Study," Frontiers in Nutrition, 2021.

- Indika, N.-L.R.; Frye, R.E.; Rossignol, D.A.; Owens, S.C.; Senarathne, U.D.; Grabrucker, A.M.; Perera, R.; Engelen, M.P.K.J.; Deutz, N.E.P. The Rationale for Vitamin, Mineral, and Cofactor Treatment in the Precision Medical Care of Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robea, M.-A.; Luca, A.-C.; Ciobica, A. Relationship between Vitamin Deficiencies and Co-Occurring Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Medicina 2020, 56, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent, S.; Lawton, B.; Warren, T.; Widjaja, F.; Dang, K.; Fahey, J.W.; Cornblatt, B.; Kinchen, J.M.; Delucchi, K.; Hendren, R.L. Identification of urinary metabolites that correlate with clinical improvements in children with autism treated with sulforaphane from broccoli. Mol. Autism 2018, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Niyazov, D.M.; Rossignol, D.A.; Goldenthal, M.; Kahler, S.G.; Frye, R.E. Clinical and Molecular Characteristics of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2018, 22, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Sumit et al., "Patient care standards for primary mitochondrial disease: a consensus statement from the Mitochondrial Medicine Society," Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, vol. 19, 2017.

- Chen, L.; Shi, X.-J.; Liu, H.; Mao, X.; Gui, L.-N.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Y. Oxidative stress marker aberrations in children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 87 studies (N = 9109). Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, R.E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder: Unique abnormalities and targeted treatments. 2020, 35, 100829. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zou, J.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, T.; Fan, X. Alteration of peripheral cortisol and autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 928188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marazziti, D.; Stahl, S.M. Novel challenges to psychiatry from a changing world. CNS Spectrums 2021, 26, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, B.A.; Mendoza, S.; Abdullah, M.; Wegelin, J.A.; Levine, S. Cortisol circadian rhythms and response to stress in children with autism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Gerasimos et al., "Stress System Activation in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Dis-order," Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 15, pp. 756628 -, 2022.

- Zinke, K.; Fries, E.; Kliegel, M.; Kirschbaum, C.; Dettenborn, L. Children with high-functioning autism show a normal cortisol awakening response (CAR). Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35, 1578–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, B.A.; Schupp, C.W.; Levine, S.; Mendoza, S. Comparing cortisol, stress, and sensory sensitivity in children with autism. Autism Res. 2009, 2, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’osso, L.; Massoni, L.; Battaglini, S.; Cremone, I.M.; Carmassi, C.; Carpita, B. Biological correlates of altered circadian rhythms, autonomic functions and sleep problems in autism spectrum disorder. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2022, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, E.G.; Nicholas, J.S.; Brady, K.T.; Carpenter, L.A.; Hatcher, C.R.; Meekins, K.A.; Furlanetto, R.W.; Charles, J.M. Enhanced Cortisol Response to Stress in Children in Autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinović-Ćurin, J.; Marinović-Terzić, I.; Bujas-Petković, Z.; Zekan, L.; Škrabić, V.; Đogaš, Z.; Terzić, J. Slower cortisol response during ACTH stimulation test in autistic children. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2007, 17, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, H. Şimşek, ; Şahin, S. Elevated levels of cortisol, brain-derived neurotropic factor and tissue plasminogen activator in male children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2078–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jue, H.; Fang-Fang, L.; Dan-Fei, C.; Nuo, C.; Chun-Lu, Y.; Ke-Pin, Y.; Jian, C.; Xiao-Bo, X. A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study about the role of morning plasma cortisol in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1148759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrangelo, M.; Tolve, M.; Artiola, C.; Bove, R.; Carducci, C.; Carducci, C.; Angeloni, A.; Pisani, F.; Leuzzi, V. Phenotypes and Genotypes of Inherited Disorders of Biogenic Amine Neurotransmitter Metabolism. Genes 2023, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisato, V.; Silva, J.A.; Longo, G.; Gallo, I.; Singh, A.V.; Milani, D.; Gemmati, D. Genetics and Epigenetics of One-Carbon Metabolism Pathway in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Sex-Specific Brain Epigenome? Genes 2021, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Qiu, Y.; Li, Y.; Cong, X. Genetics of autism spectrum disorder: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Kyong-Oh et al., "Phenotypic overlap between atopic dermatitis and autism," BMC Neuroscience, vol. 22, pp. 43 -, 2021.

- Theoharides, T.C.; Angelidou, A.; Alysandratos, K.-D.; Zhang, B.; Asadi, S.; Francis, K.; Toniato, E.; Kalogeromitros, D. Mast cell activation and autism. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2012, 1822, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. B. Russell, "A possible central mechanism in autism spectrum disorders, part 3: the role of excitotoxin food additives and the synergistic effects of other environmental toxins," Alternative therapies in health and medicine, vol. 15, pp. 56 - 60, 2009.

- Rossignol, D.A.; Frye, R.E. The Effectiveness of Cobalamin (B12) Treatment for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepmala et al., "Clinical trials of N-acetylcysteine in psychiatry and neurology: A systematic review," Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, vol. 55, pp. 294 - 321, 2015. 2015.

- L. Yi-Ying et al, "Antioxidant interventions in autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis," Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 2021.

- Satinder, A.; Suvasini, S. "Diagnosis and Management of Acute Encephalitis in Children," Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vreeland, A.; Calaprice, D.; Or-Geva, N.; Frye, R.E.; Agalliu, D.; Lachman, H.M.; Pittenger, C.; Pallanti, S.; Williams, K.; Ma, M.; et al. Postinfectious Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Sydenham Chorea, Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal Infection, and Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Disorder. Dev. Neurosci. 2023, 45, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. C. Jennifer et al., "Autoantibody Biomarkers for Basal Ganglia Encephalitis in Sydenham Chorea and Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated With Streptococcal Infections," Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2020.

- R. W. Ellen, "A Pediatric Infectious Disease Perspective on Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Dis-order Associated With Streptococcal Infection and Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome," Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 2019.

- Chang, K.; Frankovich, J.; Cooperstock, M.; Cunningham, M.W.; Latimer, M.E.; Murphy, T.K.; Pasternack, M.; Thienemann, M.; Williams, K.; Walter, J.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of Youth with Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS): Recommendations from the 2013 PANS Consensus Conference. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Cavestro, C.; Alam, S.S.; Kundu, S.; Kamal, M.A.; Reza, F. Encephalitis in Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Evidence-Based Analysis. Cells 2022, 11, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Ren, Y.; Lv, T. Encephalitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 945–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Siddiqa, A.; Ali, N.; Dhallu, M. COVID-19 and the Brain: Acute Encephalitis as a Clinical Manifestation. Cureus 2020, 12, e10784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Sofia et al., "Treatment of PANDAS and PANS: a systematic review," Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 2018.

- Gause, C.; Morris, C.; Vernekar, S.; Pardo-Villamizar, C.; Grados, M.A.; Singer, H.S. Antineuronal antibodies in OCD: Comparisons in children with OCD-only, OCD+chronic tics and OCD+PANDAS. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009, 214, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.M. et al., "Prevalence of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) in children and adolescents with eating disorders," Journal of Eating Disorders, 2022.

- Sarah and W. Kyle, "PANDAS and PANS: An Inflammatory Hypothesis for a Childhood Neuropsy-chiatric Disorder," Pediatric Neuropsychiatry, 2019.

- Thom, R.P.; Keary, C.J.; Palumbo, M.L.; Ravichandran, C.T.; Mullett, J.E.; Hazen, E.P.; Neumeyer, A.M.; McDougle, C.J. Beyond the brain: A multi-system inflammatory subtype of autism spectrum disorder. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 3045–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, M.J.; Ha, S.; Hwang, J.; Koyanagi, A.; Dragioti, E.; Radua, J.; Smith, L.; Jacob, L.; de Pablo, G.S.; et al. Association between autism spectrum disorder and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. Baumeister et al., "Inflammatory biomarker profiles of mental disorders and their relation to clinical, social and lifestyle factors," Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014.

- Lesca, G.; Rudolf, G.; Labalme, A.; Hirsch, E.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Genton, P.; Motte, J.; Martin, A.d.S.; Valenti, M.; Boulay, C.; et al. Epileptic encephalopathies of the Landau-Kleffner and continuous spike and waves during slow-wave sleep types: Genomic dissection makes the link with autism. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 1526–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolfenden, S.; Sarkozy, V.; Ridley, G.; Coory, M.; Williams, K. A systematic review of two outcomes in autism spectrum disorder – epilepsy and mortality. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2012, 54, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorjipour, H.; Darougar, S.; Mansouri, M.; Karimzadeh, P.; Amouzadeh, M.H.; Sohrabi, M.R. Hypoallergenic diet may control refractory epilepsy in allergic children: A quasi experimental study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Joks, R.; Durkin, H.G. Allergic disease is associated with epilepsy in childhood: a US population-based study. Allergy 2014, 69, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Malhi et al., “Integration of proteinogenic amino acids in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia,” Med4, vol. 65, pp. 120-135, 2023.

- Y. N. L. Huiyun Fan, R. Zhang, "Early death and causes of death of patients with autism spectrum dis-orders: A systematic review," vol. 55 2, 2023.

- M. W. Elizabeth, "Autism, Physical Health Conditions, and a Need for Reform," JAMA Pediatrics, 2023.

- K. V. et al., "Comorbidities in autism spectrum disorder and their etiologies," Translational Psychiatry, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).