1. Introduction

Radial nerve palsies represent a complex clinical condition that can lead to significant functional limitations and disability for affected patients [

1]. The radial nerve plays a crucial role in the extension of the elbow, wrist and fingers, and is responsible for most of the strength and coordination required for a proper movement of the upper limbs [

2]. The incidence of radial nerve palsy can vary depending on the etiology, with traumatic, compressive or idiopathic causes that can impair nerve function [

3].

Patients with this condition often have difficulty performing essential daily actions, such as grasping and lifting objects, significantly limiting their quality of life and ability to perform work activities [

4].

The management of radial nerve palsy has been the subject of ongoing research and development in orthopaedics and nerve surgery [

5]. Among the various treatment options available, tendon transfers have proven to be an effective surgical strategy for restoring motor function in patients with radial nerve damage. Tendon transfer is a surgical procedure in which the tendon of a functioning muscle is moved from its original position to reattach it to a new position in order to restore impaired motor function [

6].

The main goal of tendon transfers in radial nerve palsies is to restore the ability to extend the elbow, wrist and fingers, allowing patients to perform essential daily activities and thus improving their quality of life. Some schemes have been developed for evaluating the results of tendon transfers in radial nerve palsy, the most logical and commonly used being the evaluation schemes that assess the range of active joint movements.

The primary aim of our study is to present a new evaluation protocol, an original scheme for tendon transfer outcomes based on functional movements of the wrist and finger joints that includes all variables to be evaluated in the patients’ outcome, considering objective and subjective parameters; with a unique, complete, reproducible and reliable scheme that minimizes the examiner’s subjective error in the evaluation of all clinical cases.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective study of clinical evaluation in patients who underwent tendon transfer for post-traumatic radial nerve injury. The study included forty-five patients, twenty-nine men and sixteen women, treated at G. Pini and C.T.O. Microsurgery and Hand Surgery Unit in Milan and C.T.O. in Turin, between 2010 and 2022. Eighteen patients who had brachial plexus injury were excluded from the study. In these cases, as the paralysis affected more than one nerve, the sample would not have been homogeneous. Sixteen patients were also excluded because they escaped follow-up or because they had died. We therefore included eleven patients who had a pure radial nerve lesion, nine men and two women. The average age of the patients was thirty-six years (19-83 yy).

In eight patients, the dominant arm was affected. In six patients the lesion was at the level of the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) as a result of the forearm fracture, thus involving a low paralysis; in the remaining five patients the radial paralysis was high (before the ramification of radial nerve in PIN and sensory branch) as a result of a humerus fracture. All patients were evaluated after a minimum follow-up of one year following the surgery, with an average follow-up of three years and six months. One senior surgeon performed all the operations.

In all cases the same technique, described by Riordan [

7], was used: Flexor Carpi Ulnaris (FCU) pro common finger extensor (EDC), used to restore finger extension; Pronator Teres (PT) pro Extensor Radialis Carpi Brevis (ECRB) to restore wrist extension; and Palmaris Longus (PL) pro Extensor Pollicis Longus (EPL) to restore thumb extension using the re-routing technique [

8], in which the EPL is rerouted from Lister’s tubercle to the anatomical snuffbox to allow recovery of both thumb extension and abduction. The postoperative management was the same for all the patients.

Surgical Technique

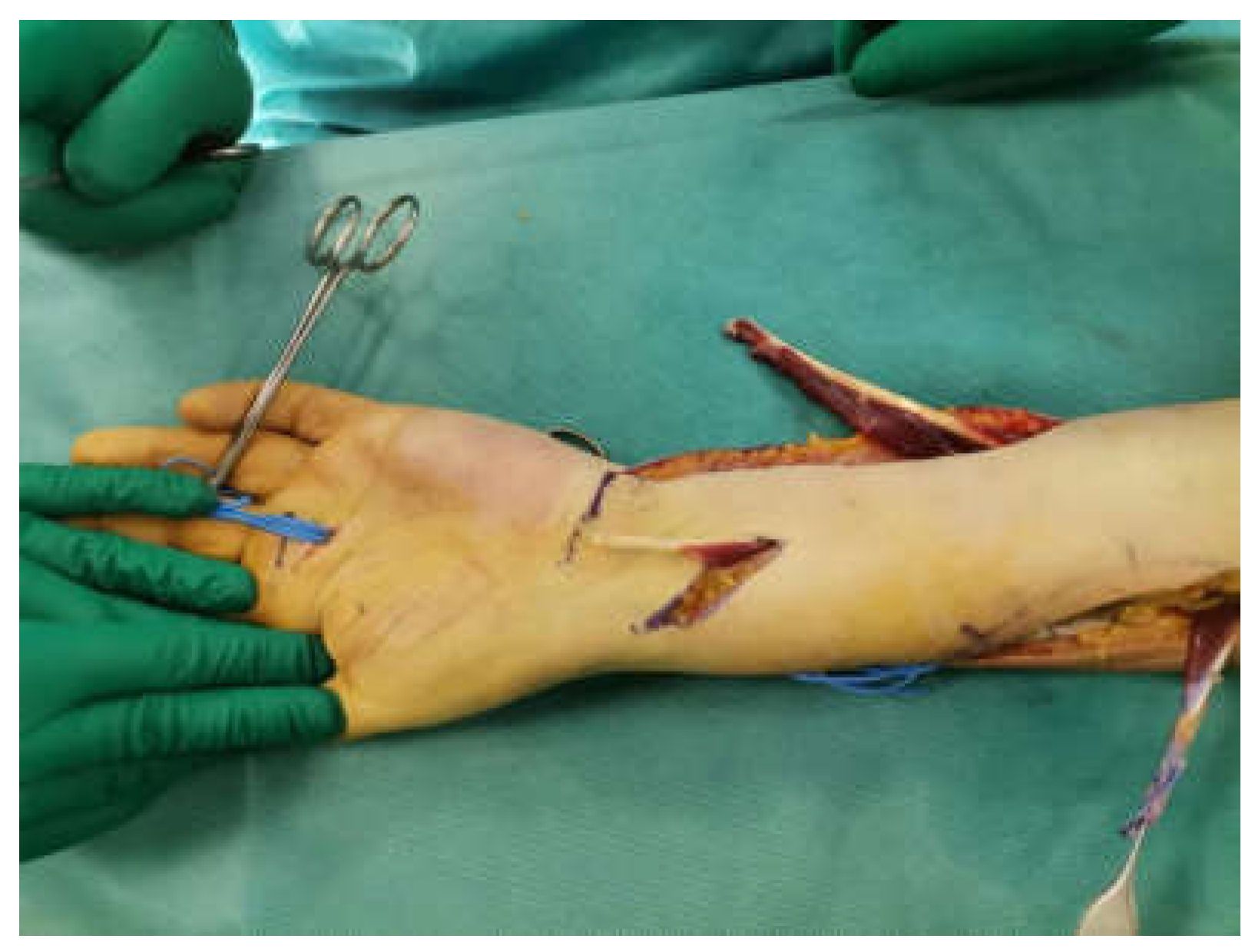

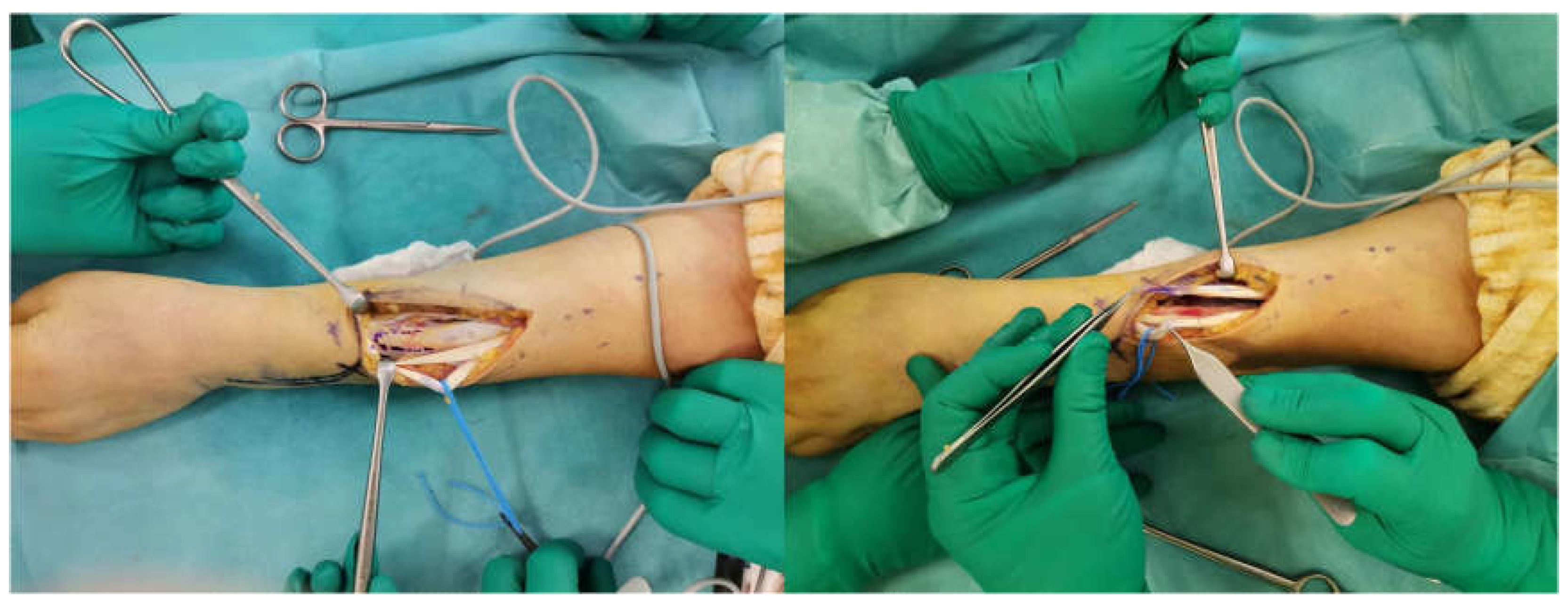

The surgical technique involves plexus anaesthesia with pneumo-ischemia of the arm. The first volar J-incision is made longitudinally at the FCU from the distal half of the forearm to the wrist and the distal transverse extension is extended to the PL. The FCU tendon is retrieved just proximal to the pisiform and released as far as the proximal extension of the incision allows. The FCU muscular belly is very wide and, therefore, it is preferred to remove part of the belly at the myotendinous insertion to facilitate later mobilization and avoid bulk around the ulnar edge of the forearm (

Figure 1).

The second dorsal incision, of approximately 5 cm, is made 2 cm distal to the medial epicondyle and directed towards Lister’s tubercle. The deep fascia of the FCU and all fascial shoots are then removed in order to mobilize it properly. The third incision begins in the volar-radial aspect of the forearm and is directed dorsally around its radial border in the PT insertion region.

The insertion on the radius of the PT is identified and disengaged, paying attention to take a strip of periosteum together to ensure that the length is sufficient (

Figure 2). The PT is then transferred subcutaneously (above the BR and ECRL) and sutured according to the Pulvertaft technique [

9], with 4-0 non-resorbable thread, just distal to the myotendinous junction of the ECRB; under maximum tension and with the wrist at 45° extension.

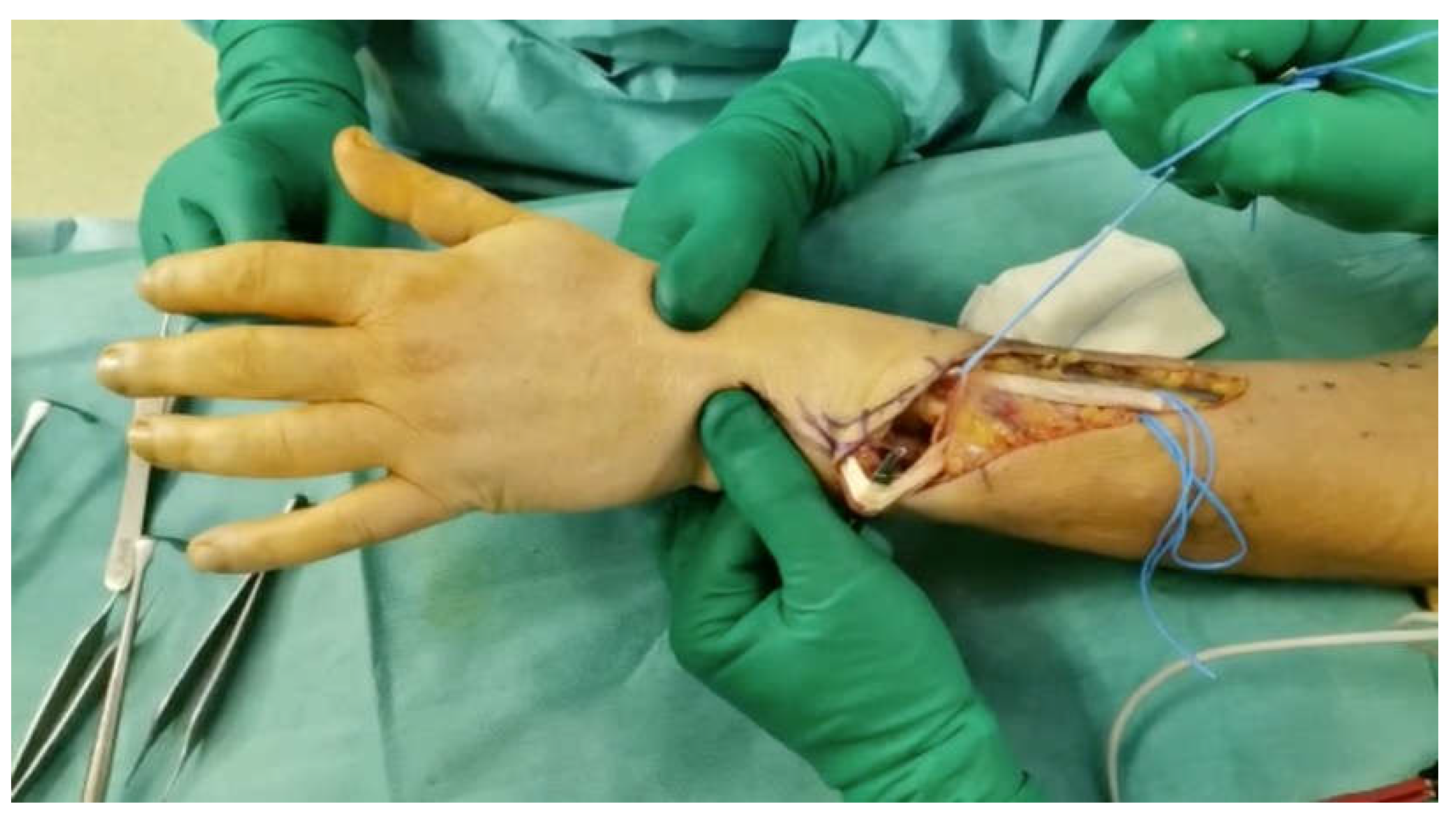

At this point the FCU is transferred subcutaneously to the third incision, where it is sutured distal to the myotendinous junction at each tendon of the EDC, just proximal to the extensor retinaculum (

Figure 3), with 4-0 non-absorbable thread, under maximum tension with the wrist in the neutral position. It is essential that the traction line is as straight as possible from the medial epicondyle to the EDC.

Through the third incision the EPL is dissected at the myotendinous junction proximal to the extensor retinaculum, from here it is pulled out of its channel and redirected through a subcutaneous tunnel, at the level of the anatomical snuffbox, to the I metacarpal and brought volarly [

8]. The PL is disengaged at the wrist and sutured to the EPL, according to the Pulvertaft technique, with 4-0 non-absorbable thread in maximum tension at neutral wrist (

Figure 4). The PL is absent in approximately 14% of the population [

10,

11]; in these cases the EPL is integrated with the EDC, but the independence of the first finger is lost.

Before closing the wounds, tension should be tested by passively moving the wrist to show the synergic action of the new transfers. With the wrist in extension, fingers flexion into the palm should be possible and, with the wrist in flexion, full extension of the metacarpo-phalanges should be possible, but not hyperextension. In patients who presented low paralysis PT transfer pro ECRB was not performed.

The post-operative protocol involves immobilization in a brachio-antibrachio-metacarpal (BAM) plaster cast for three weeks; with the proximal interphalangeal joints (PIP) free, the forearm pronated approximately 15°-30°, the wrist extended to 45°, the metacarpo-phalangeal (MP) joints slightly flexed to 10°-15° and the thumb in full extension and abduction. After that, a short brace is applied for a further three weeks, which the patient can remove several times per day to begin the rehabilitation treatment. A good recovery of function is generally observed after three months. Maximum recovery generally occurs six months after surgery.

3. Results

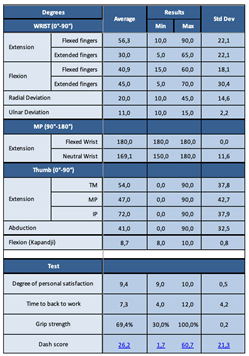

All patients were evaluated after a minimum follow-up of one year after surgery, with an average follow-up of three years and six months. Measurements were performed with a goniometer. We used an original evaluation protocol that includes all possible variables to be evaluated, specifically: wrist extension and flexion with flexed and extended fingers, radial deviation (RD) and ulnar deviation (UD) of the wrist; MP extension of the long fingers with flexed wrist and in neutral position; extension-abduction of the thumb by assessing the degrees of the trapezio-metacarpal, MP and interphalangeal (IP) joints; thumb flexion with the Kapandij test; the flute test for finger independence and strength with Jamar’s dynamometer, compared with the non-affected hand. We also assessed the degree of personal satisfaction, time to return to work and the DASH score (

Table 1).

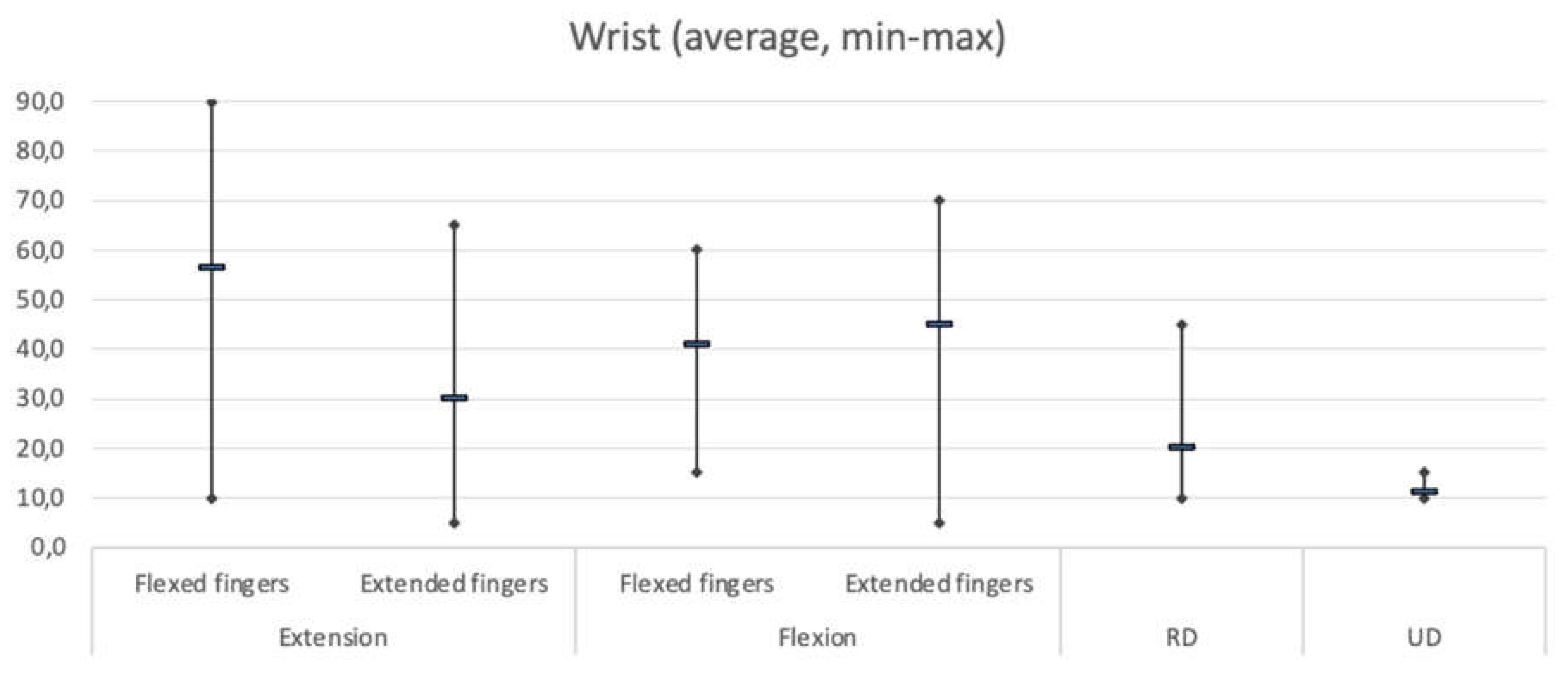

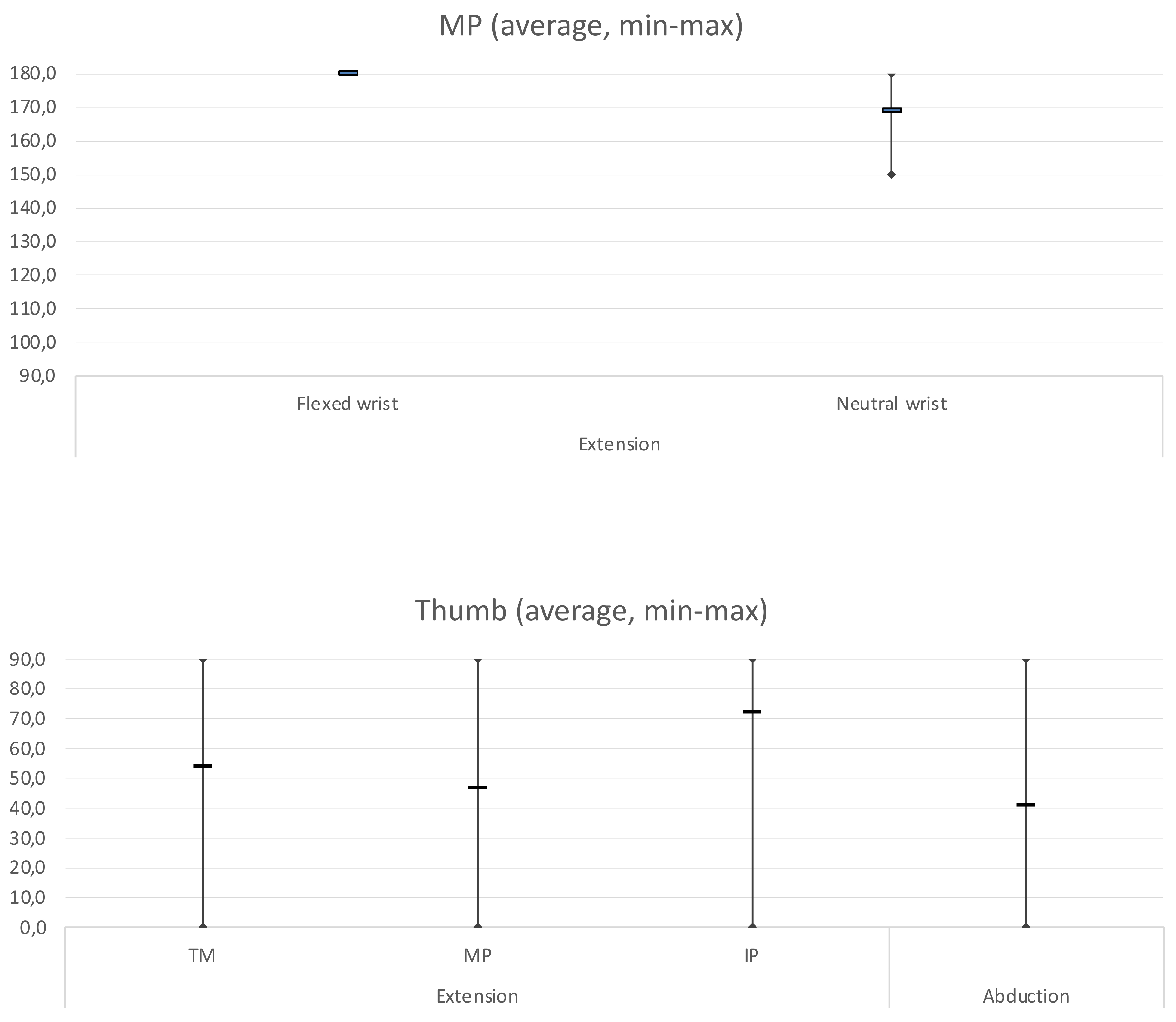

As far as range of motion (ROM) is concerned, the

Table 2 and Graph 1 show in detail: the average degrees of movement obtained for each individual assessment, with minimum and maximum ranges and the standard deviation.

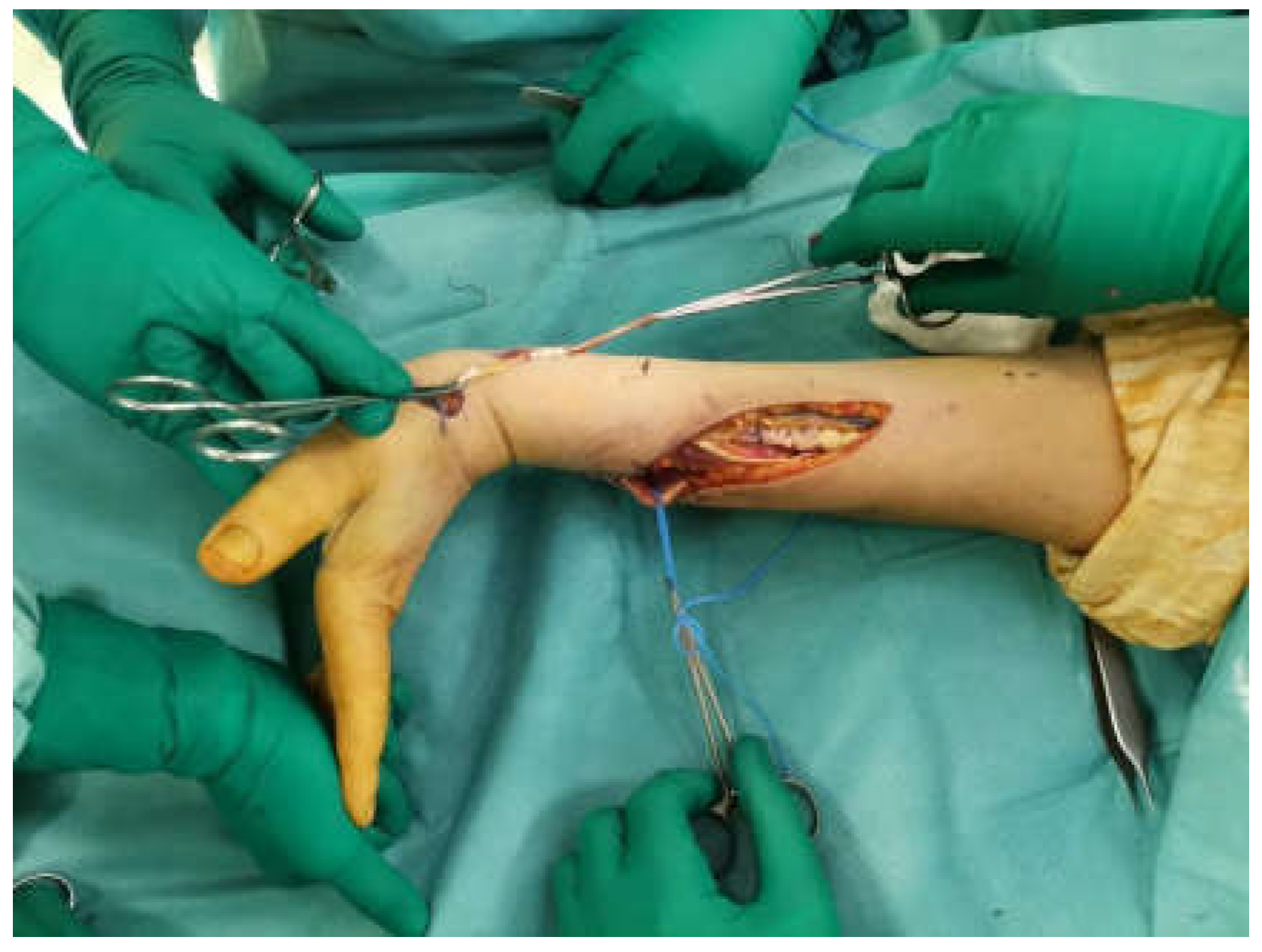

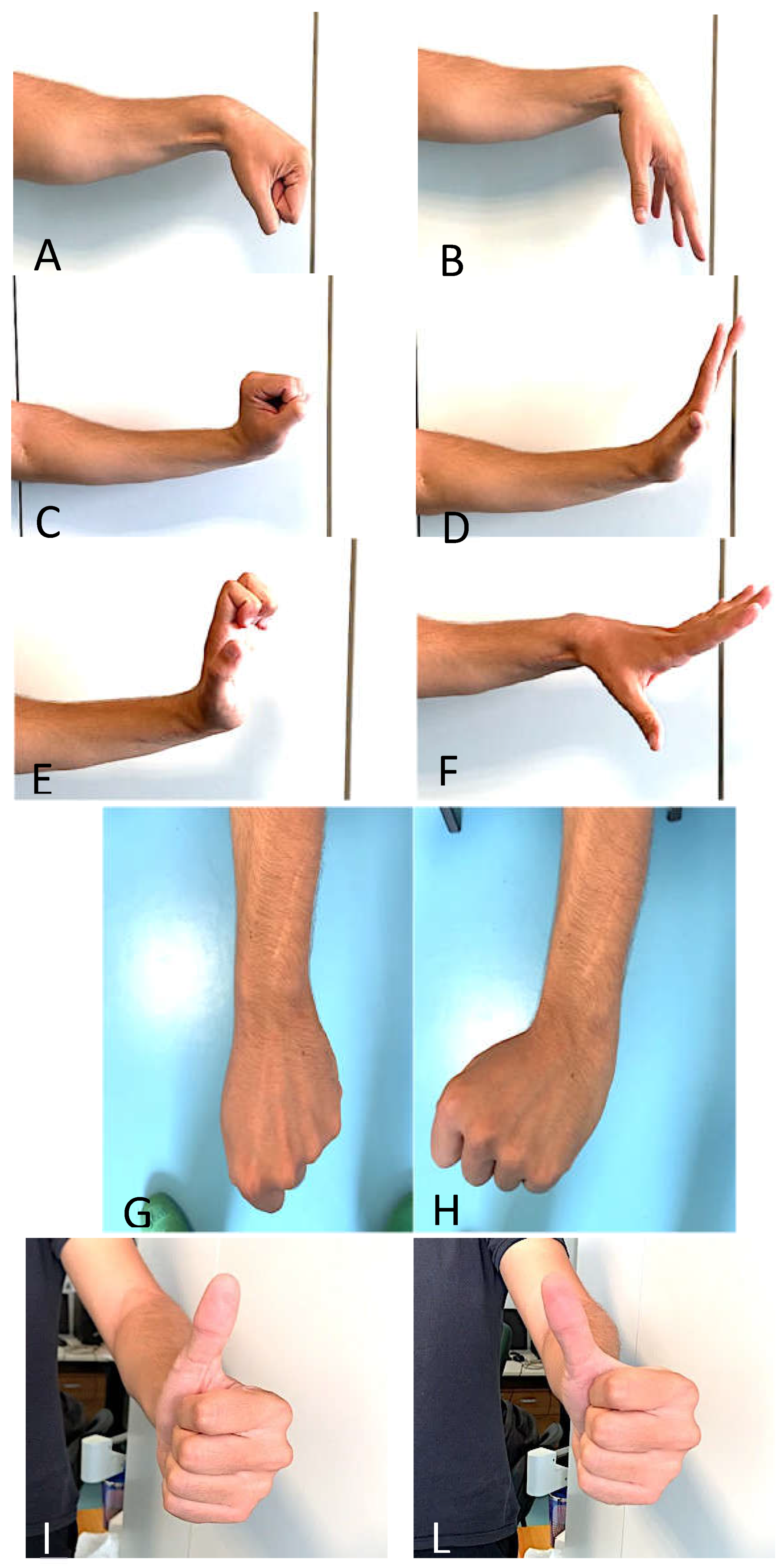

Figure 5 shows examples of clinical results.

Graph 1.

shows average of wrist ROM with flexed and extended fingers and RD-UL, average of MP extension and average of thumb extension-abduction.

Graph 1.

shows average of wrist ROM with flexed and extended fingers and RD-UL, average of MP extension and average of thumb extension-abduction.

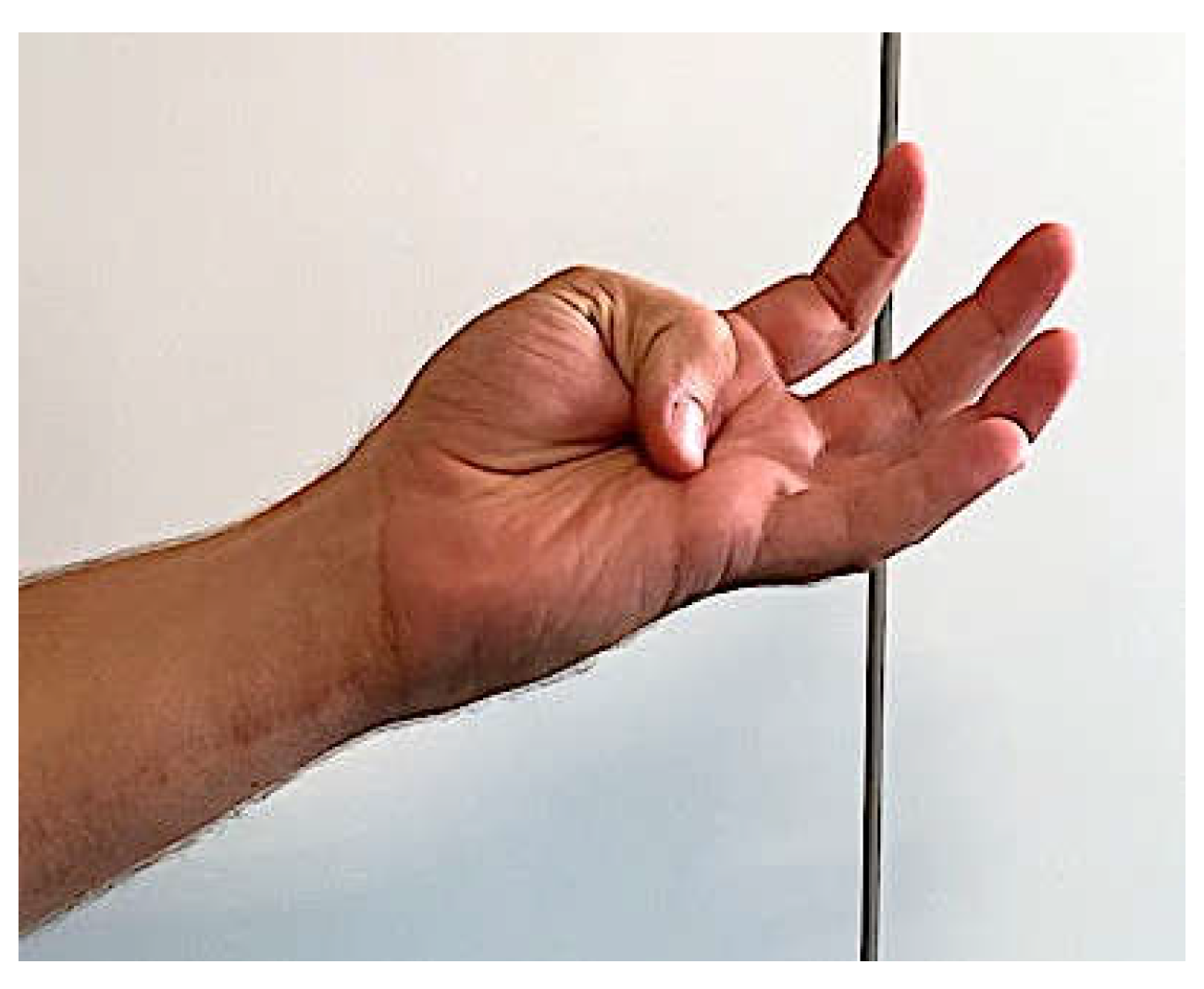

The Kapandji test evaluation showed an average of 8.7, meaning that on average patients were able to touch the base of the fifth finger (

Figure 6).

Grip strength was assessed using Jamar’s dynamometer and evaluated against the strength of the healthy arm. On average, the patients showed 70% of the contralateral strength. The DASH score showed an average value of 26.2%, with good patient-reported results and a minimal degree of disability. All patients were very satisfied and had no limitations in their daily activities, with return to work in all cases after an average period of seven months after surgery.

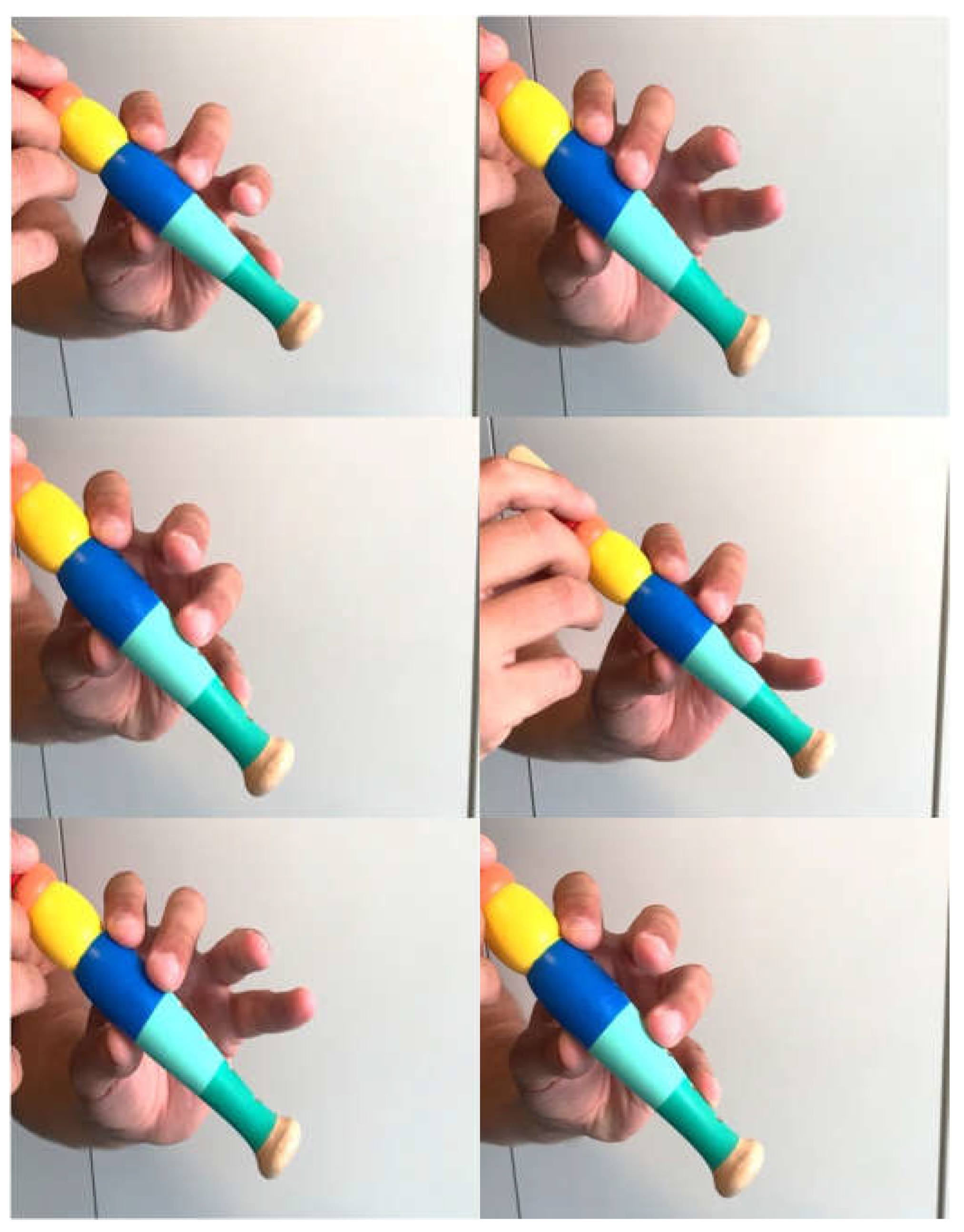

In three patients, we noticed a certain degree of finger independence by means of the flute test. Specifically, the patient was asked to ‘play the flute’ by pressing the holes with single and paired fingers with MP in extension. We found that the three patients performed more easily with single finger, with II and IV fingers together and with III-IV fingers together. This can be explained by the independence of the flexor tendons to overcome extensor resistance (

Figure 7).

There were no major complications, such as infection or suture rupture. One patient, aged 83, had a fall, eight months after the operation, resulting in a wrist fracture, treated conservatively, on the same side as the tendon transfer surgery. This undoubtedly affected the current result, as she reported that before the new trauma, she had regained most of her functions, which were then lost due to the fracture, leading to stiffness in the wrist.

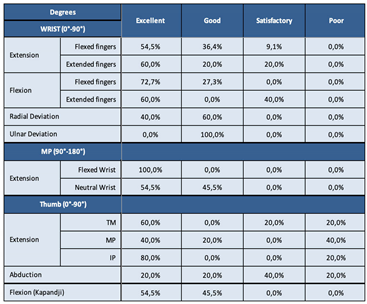

Analyzing these initial results using our rating scale, we can affirm that, on average, wrist extension was good with flexed fingers, excellent with extended fingers; wrist flexion was excellent with flexed fingers and good with extended fingers; excellent radial deviation, good ulnar deviation; MP extension was excellent with flexed wrist, good with neutral wrist; as for the thumb, TM extension was good on average, MP extension good and IP extension excellent, abduction satisfactory and flexion was good (measured with the Kapandji test).

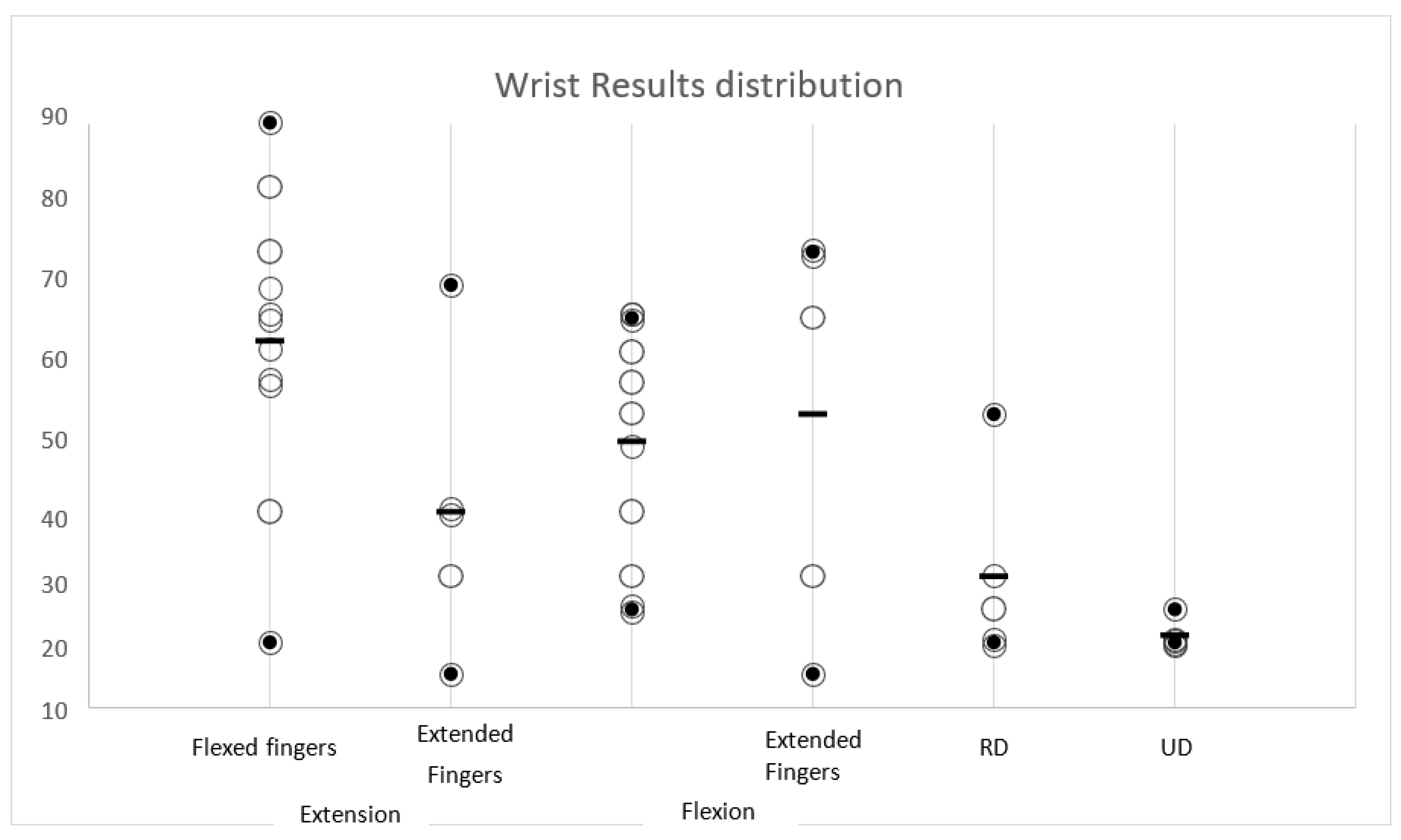

We report in

Table 3 the individual percentages and the final distribution graph of the wrist values (Graph 2).

Graph 2.

The final distribution graph of the wrist values.

Graph 2.

The final distribution graph of the wrist values.

4. Discussion

The radial nerve is frequently affected in upper extremity fractures, especially humerus fractures where the incidence reaches 12% [

12,

13]. Radial nerve injuries due to diaphyseal fracture of the humerus may be associated with Holstein-Lewis fractures: fractures of the middle/distal third of the humerus where the radial nerve twists to move anteriorly and is exposed to stretching/pulling damage due to its position between two fibrous fixation means (proximally the intermuscular septum and distally the Frohse’s arch) [

1,

14]. Fractures of the proximal third of the radius are also at risk of radial nerve injury. Furthermore, a great risk is iatrogenic damage due to surgical access [

15].

Because of its particular course characterized by its close relationship with the humerus, the radial nerve has several sites of possible compression: the radial tunnel at the elbow; Frohse’s arch (PIN); passage between the brachioradialis muscle tendon and extensor longus carpi (dorsal sensory branch); Wartenberg syndrome (compression of the radial sensory branch with only sensory symptoms) [

16]. Rarely, chronic compressive syndromes of the radial nerve cause clinically relevant pictures of paralysis.

The most common clinical presentation of radial nerve palsies is characterized by denervation of the extensor musculature with the characteristic ‘Wrist-Drop Sign’ [

17]. In complete paralysis, extension is maintained at the level of the interphalangeal joints, as it affects the intrinsic musculature innervated by the ulnar nerve.

Radial nerve injuries should be divided into high and low injuries depending on whether the level of injury is proximal or distal to the emergence of the PIN [

18]. In high lesions, at the level of the humeral diaphyseal middle third, denervation of the brachioradialis muscle is also present. The area of hypo-anaesthesia is the one pertaining to the superficial radial sensory nerve. In proximal paralysis (isolated proximal lesions related, for example, to iatrogenic damage during surgery in the proximal region of the humerus) or posterior plexus cord lesions, triceps denervation with elbow extension deficit is also present [

2,

3,

5].

Preservation of wrist extension in radial deviation indicates a radial nerve injury at the level of the PIN (low injury), as the branch to the radial extensor muscle of the carpus is supplied prior to the entry into the fibrotic canal.

In most cases, the nerve does not suffer real injuries but only a stretch or contusion. These are very often Sunderland grade I and II injuries [

19] and this explains their high spontaneous recovery rate, from 70 to 90%, of these injuries. In such cases, recovery is gradual but complete [

12,

13,

18]. Other times, however, we are faced with high-energy traumas that result in a complete nerve injury, with or without loss of substance. In these cases it may be necessary to perform a tendon transfer later to restore the lost function [

20]. The main indication for upper extremity tendon transfer is a peripheral nerve injury with no potential improvement [

17,

21].

There are several common tendon transfer approaches used for the treatment of radial nerve palsies [

3,

6,

18,

22]. However, literature reports only a few studies that analyze the results with evaluating score systems. The standardization of results in tendon transfers is not straightforward [

17,

26].

The heterogeneity of outcome classification remains a limitation in the evaluation of tendon transfer surgery. A recent review by Compton et al. [

5] suggested that comparisons between techniques are not possible, precisely because of the heterogeneity in reporting outcomes.

The most frequently used scales are Bincaz’s [

27] and Zachary’s [

28]. In general, however, these systems classify the results into different groups without precise indicators allowing for subjective interpretation and different endpoints in the same patient with different examiners. Furthermore, little attention is paid to the patient’s subjective functional results. Zachary’s scheme does not define the variables objectively and their variables are defined as “mild or severe” loss of function.

In a recent work, Karabeg et al. [

17] develop a new evaluation system that, like ours, aims at standardization and repeatability of the system. With the present study, we have completed and supplemented the attempt to standardize the assessment of results in palliative radial nerve palsy surgery by introducing new factors, such as the flute test, which aims at assessing the recovery, albeit partial, of finger independence, as well as the strength recovered and the subjective component of patients’ satisfaction.

Our study presents some limitations, one being the small size of patients, although it was a homogeneous group.

5. Conclusions

Tendon transfers represent a viable therapeutic option for the treatment of radial nerve palsies. Careful patient assessment and accurate planning of the surgery are mandatory to achieve positive results.

A functional assessment scheme is essential for evaluating the outcomes of this kind of surgery. We propose, with our work, a new, original, simple and reproducible evaluation protocol that includes all variables to be assessed in the outcome of tendon transfers of the radial nerve, taking into account objective parameters of active mobility of the wrist, finger and thumb joints and subjective parameters. Such protocol aims at the standardization of results in tendon transfers of radial nerve palsies outcomes that can be accepted worldwide.

Author Contributions

Reina Micaela “Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing-original draft, Funding acquisition’’; Simonetta Odella, Francesco Locatelli, Alice Clemente, Martina Macrì ‘Visualization’; Mauro Magnani ‘Conceptualization’ ; Pierluigi Tos ‘Methodology, Writing-rewiew & editing, supervision, project administration’. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests that would influence the work reported in this manuscript.

Disclaimer

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not- for-profit sectors.

References

- Ljungquist, K.L.; Martineau, P.; Allan, C. Radial nerve injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2015, 40, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, A.E.J.; Etcheson, J.; Yao, J. Radial Nerve Tendon Transfers. Hand Clin. 2016, 32, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozin, S.H. Tendon transfers for radial and median nerve palsies. J Hand Ther. 2005, 18, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, J.A.; Peljovich, A.; Kozin, S.H. Update on tendon transfers for peripheral nerve injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 2010, 35, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, J.; Owens, J.; Day, M.; Caldwell, L. Systematic Review of Tendon Transfer Versus Nerve Transfer for the Restoration of Wrist Extension in Isolated Traumatic Radial Nerve Palsy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavi, A.A.; Saied, A.; Karbalaeikhani, A. Outcome of tendon transfer for radial nerve paralysis: Comparison of three methods. Indian J Orthop. 2011, 45, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, D.C. Tendon transfers in hand surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 1983, 8, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantoni Woodside, J.; Bindra, R.R. Rerouting extensor pollicis longus tendon transfer. J Hand Surg Am. 2015, 40, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvertaft, R.G. Suture materials and tendon junctures. Am J Surg. 1965, 109, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enye, L.A.; Saalu, L.C.; Osinubi, A.A. The Prevalence of Agenesis of Palmaris Longus Muscle amongst Students in Two Lagos-Based Medical Schools. Int J Morphol. 2010, 28, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastin, S.J.; Puhaindran, M.E.; Lim, A.Y.T.; Lim, I.J.; Bee, W.H. The prevalence of absence of the palmaris longus—A study in a Chinese population and a review of the literature. J Hand Surg Am. 2005, 30, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.C.; Harwood, P.; Grotz, M.R.W. nUpper limb Radial nerve palsy associated with fractures of the shaft of the humerus A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. 2005, 87, 1647–1652.

- Schwab, T.R.; Stillhard, P.F.; Schibli, S.; Furrer, M.; Sommer, C. Radial nerve palsy in humeral shaft fractures with internal fixation: analysis of management and outcome. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018, 44, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Ilyas, A.M. Radial Nerve Palsy After Humeral Shaft Fractures: The Case for Early Exploration and a New Classification to Guide Treatment and Prognosis. Hand Clin. 2018, 34, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korompilias, A.V.; Lykissas, M.G.; Kostas-Agnantis, I.P.; Vekris, M.D.; Soucacos, P.N.; Beris, A.E. Approach to radial nerve palsy caused by humerus shaft fracture: Is primary exploration necessary? Injury. 2013, 44, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgiel, A.; Karauda, P.; Zielinska, N.; Tubbs, R.S.; Olewnik, Ł. Radial nerve compression: anatomical perspective and clinical consequences. Neurosurg Rev. 2023, 46, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabeg, R. New Functional Evaluation Scheme—Modality of the Results of Forearm Tendon Transfers Evaluation in Cases of Irreparable Radial Nerve Injury. Med Arch (Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina). 2020, 74, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabeg, R. Assessment of the Forearm Tendon Transfer with Irreparable Radial Nerve Injuries Caused by War Projectiles. Med Arch (Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina). 2019, 73, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SS A classification of peripheral nerve injuries producing loss of function. Brain. 1951, 74, 491–516. [CrossRef]

- Siret, P.; Belot, N.; Langlais, F.; Ropars, M.; Dre, T.; Unit, R.S. Article in Press Long-Term Results of Tendon Transfers in Radial and Posterior Interosseous. Hand Surg. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, R.R. Tendon transfers for failed nerve reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 2003, 30, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.F.; Machado, G.R. Tendon Transfers for Radial, Median, and Ulnar Nerve Injuries: Current Surgical Techniques. Clin Plast Surg. 2011, 38, 621–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammer, D.; Chung, K. Tendon Transfers Part I: Principles of Transfer and Transfers for Radial Nerve Palsy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009, 123, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, P.W.; Beach, R.B.; Thompson, D.E. Relative tension and potential excursion of muscles in the forearm and hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1981, 6, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhalter, W.E. Early tendon transfer in upper extremity peripheral nerve injury. Clin. Orthop. 1974, 104, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.S.; Barr, M.L.; Kim, D.; Jones, N.F. Tendon Transfers, Nerve Grafts, and Nerve Transfers for Isolated Radial Nerve Palsy: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Hand. 2023, 155894472211505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bincaz, L.E.; Cherifi, H.; Alnot, J.Y. Les transferts palliatifs de réanimation de l’extension du poignet et des doigts. À propos de 14 transferts pour paralysie radiale et dix transferts pour lésion plexique. Chir Main. 2002, 21, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachary, R.B. Tendon transplantation for radial paralysis. Br J Surg. 1946, 33, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).