Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

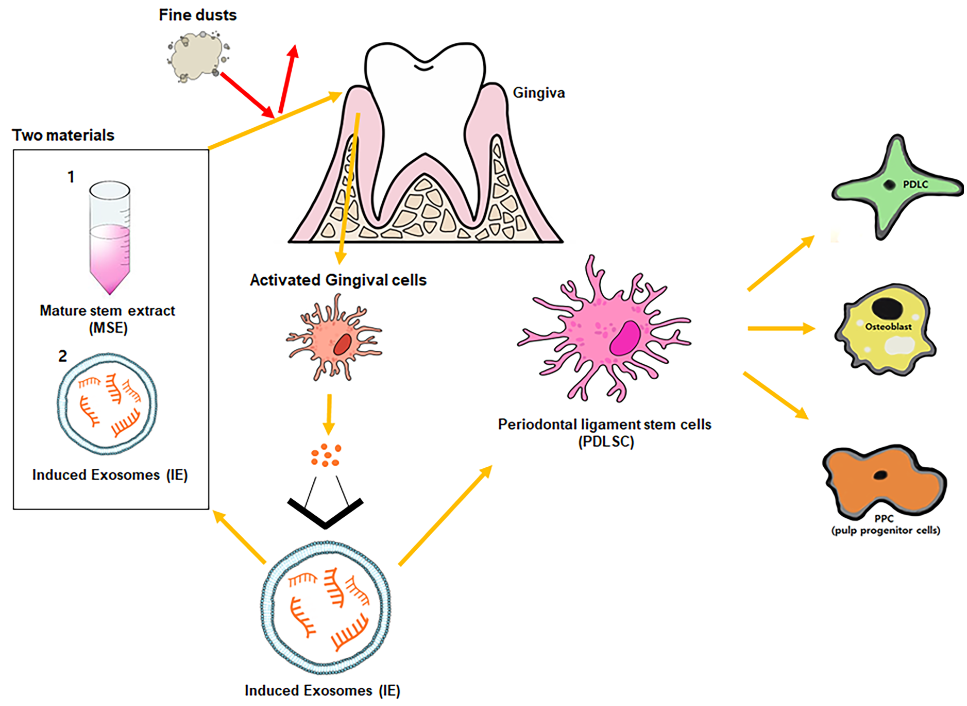

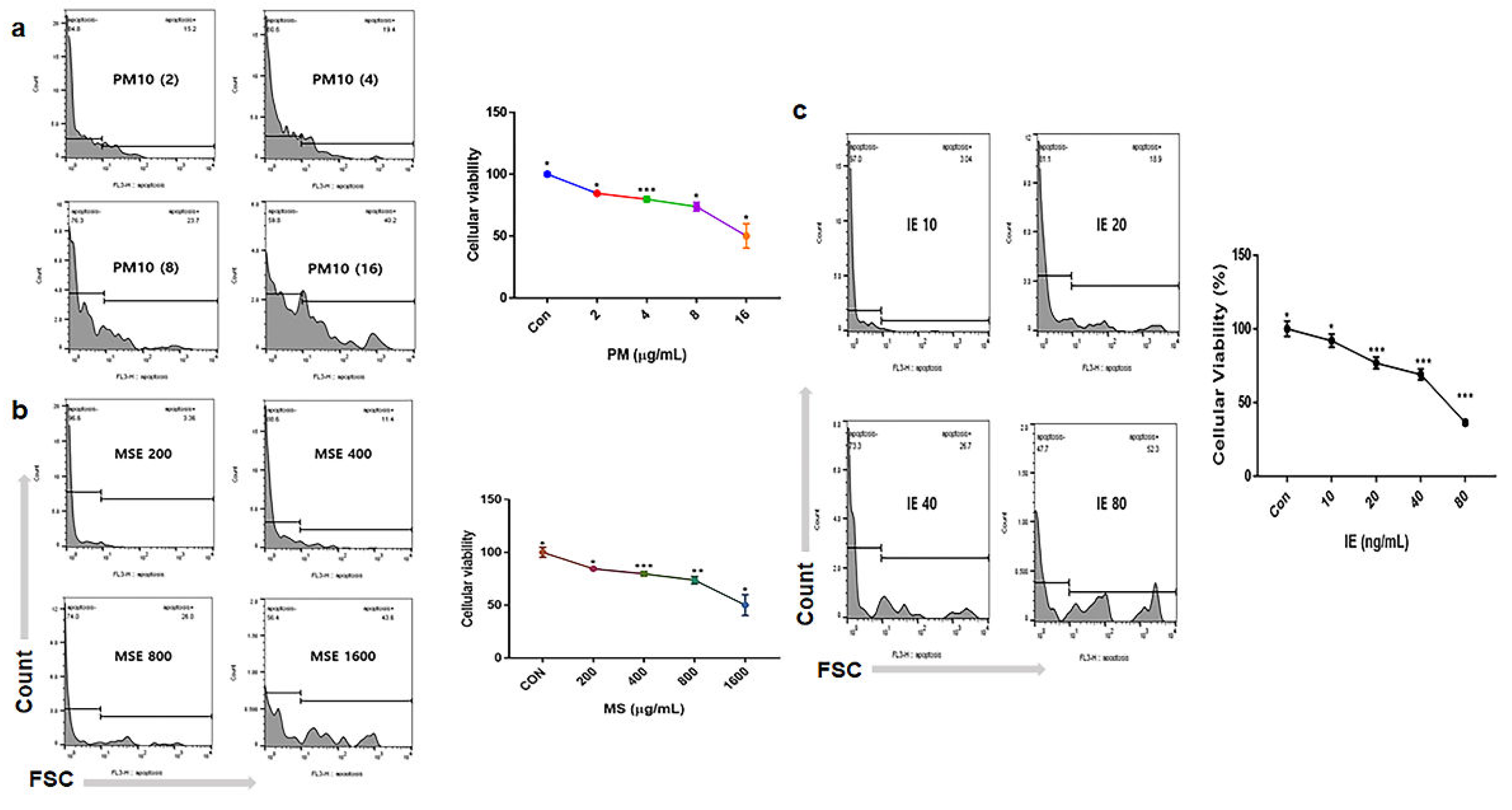

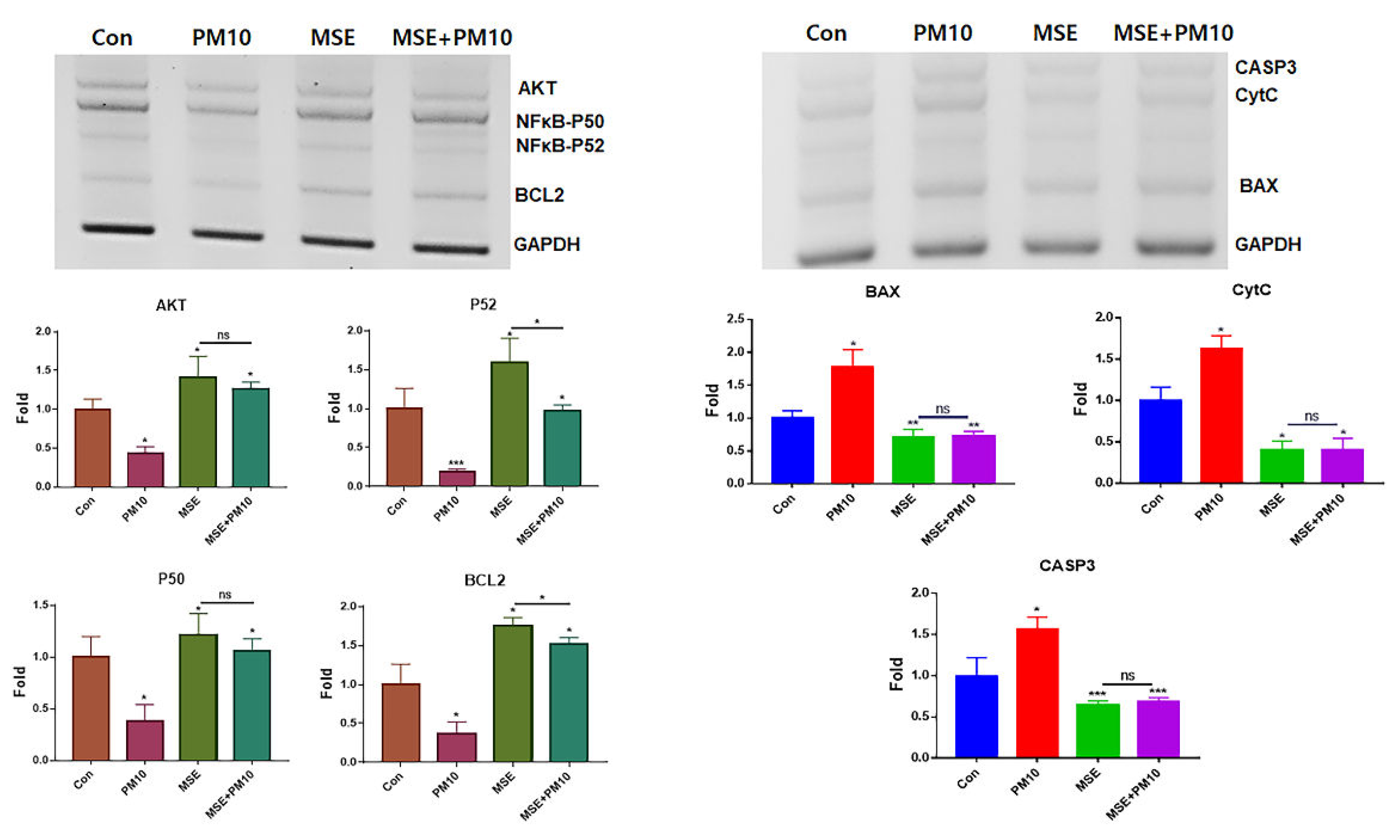

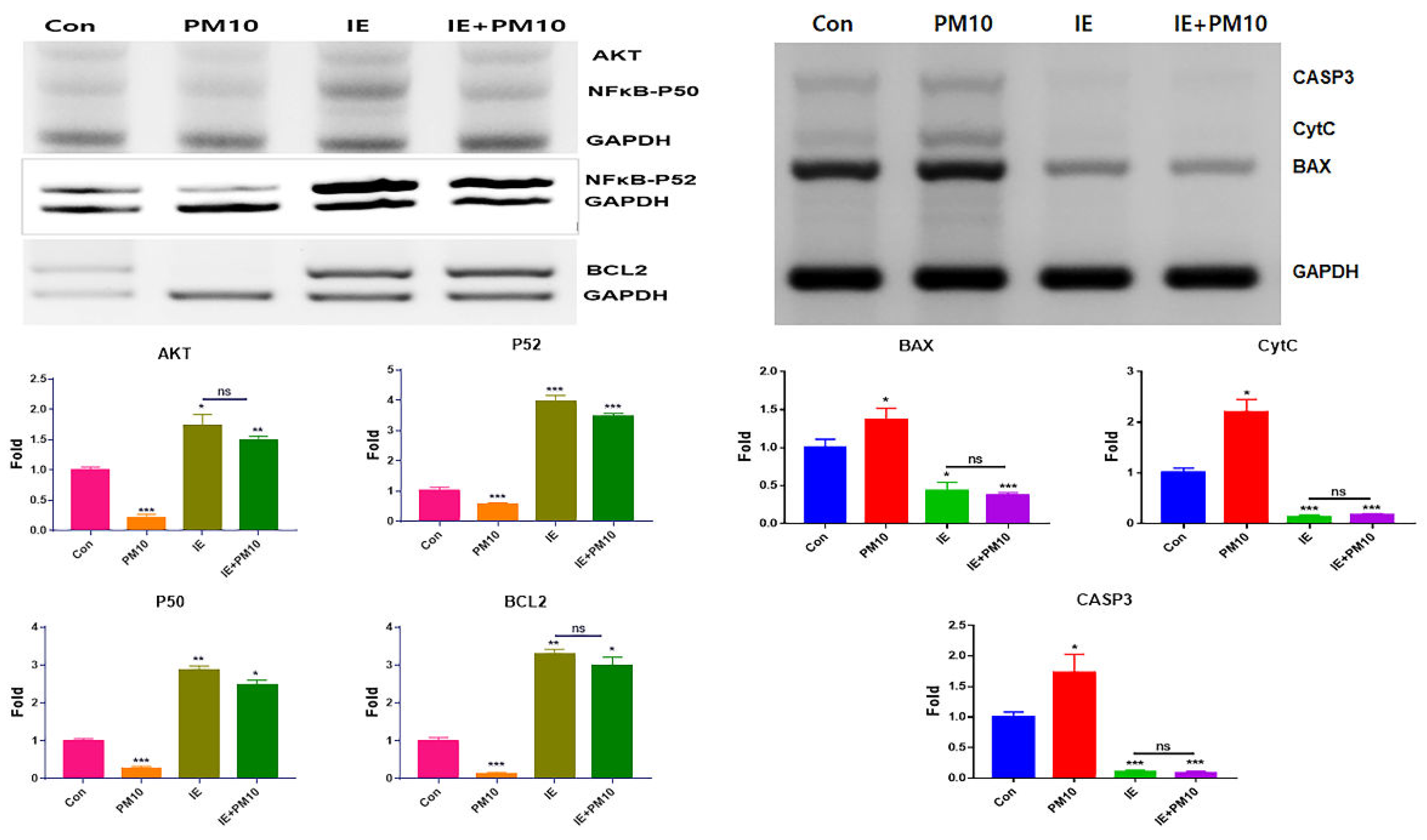

2.1. Protection of Gingival Cells Against Fine Dust

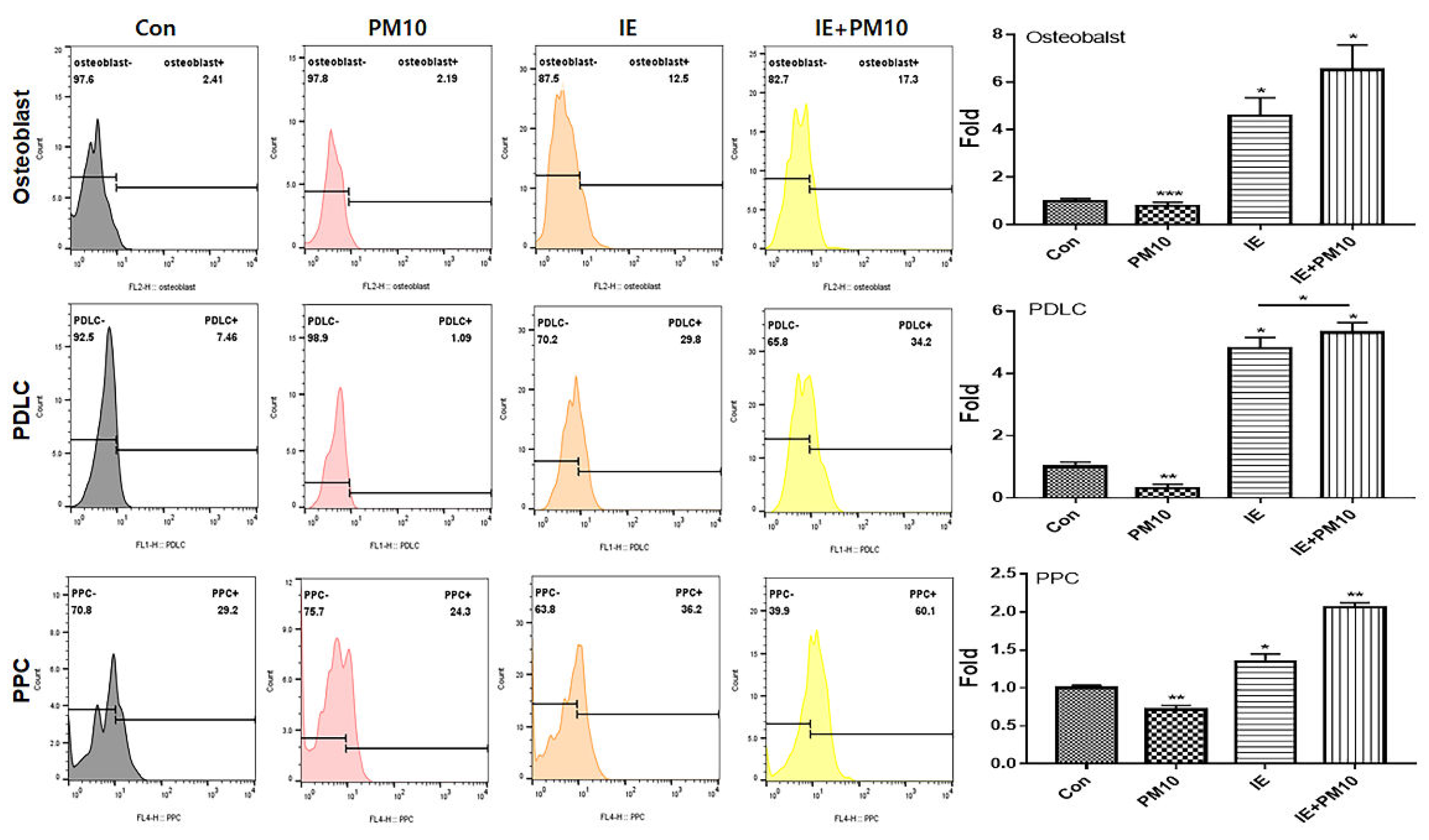

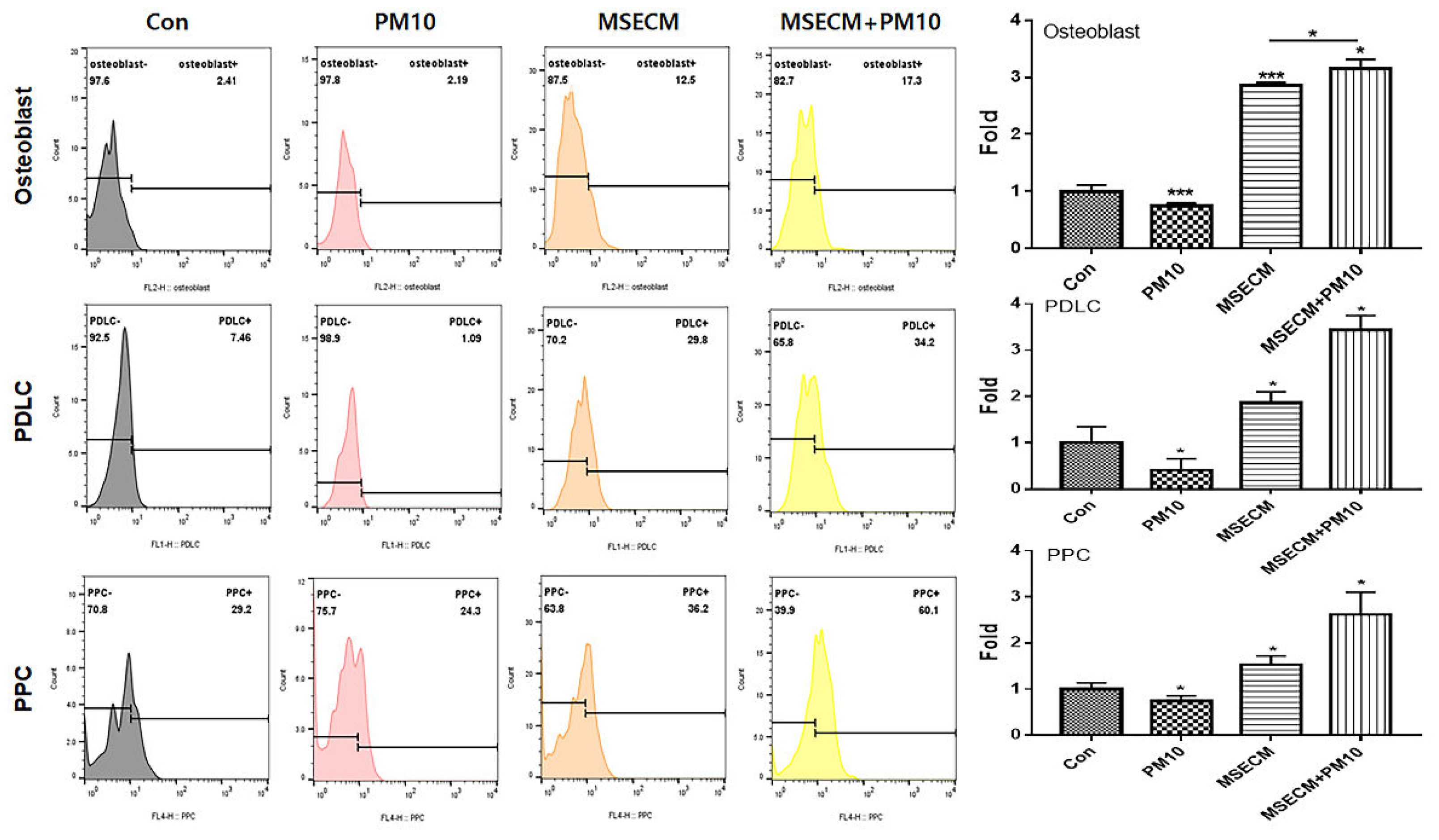

2.2. Activation of Osteogenic Differentiation By The Two Materials

2.3. Activation of PDLC Differentiation by the Two Materials

2.4. Activation of PPC Differentiation by the Two Materials

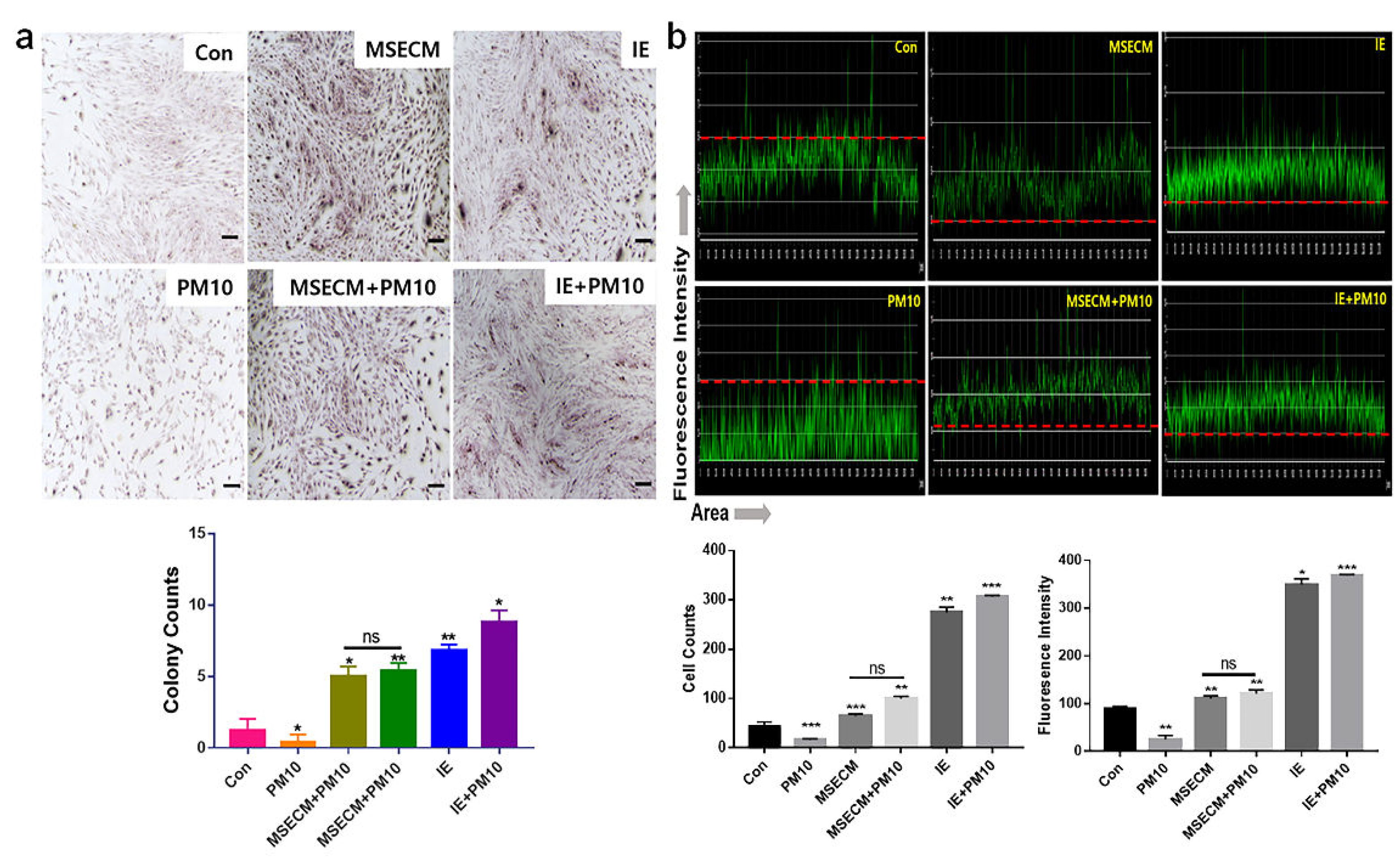

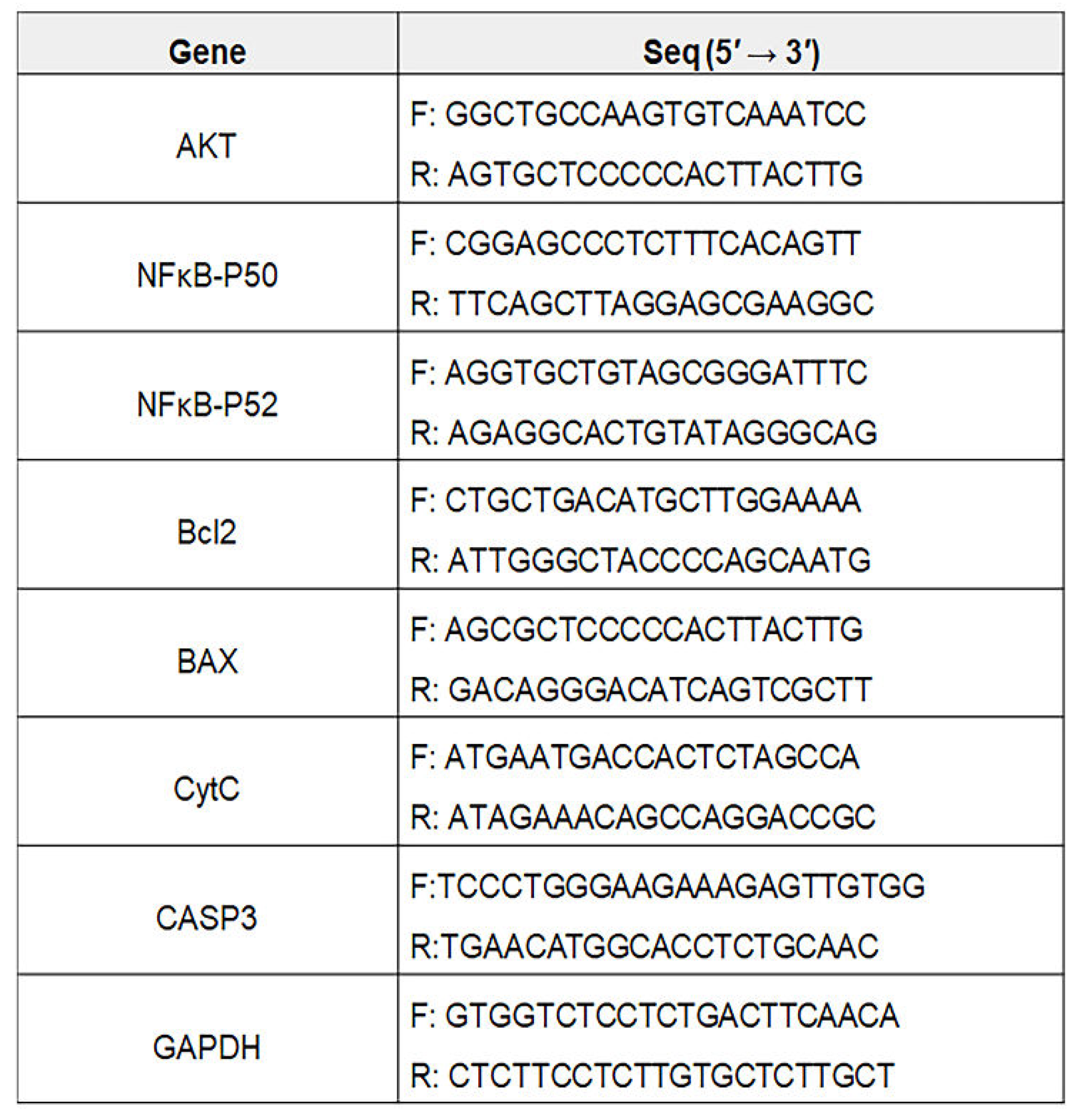

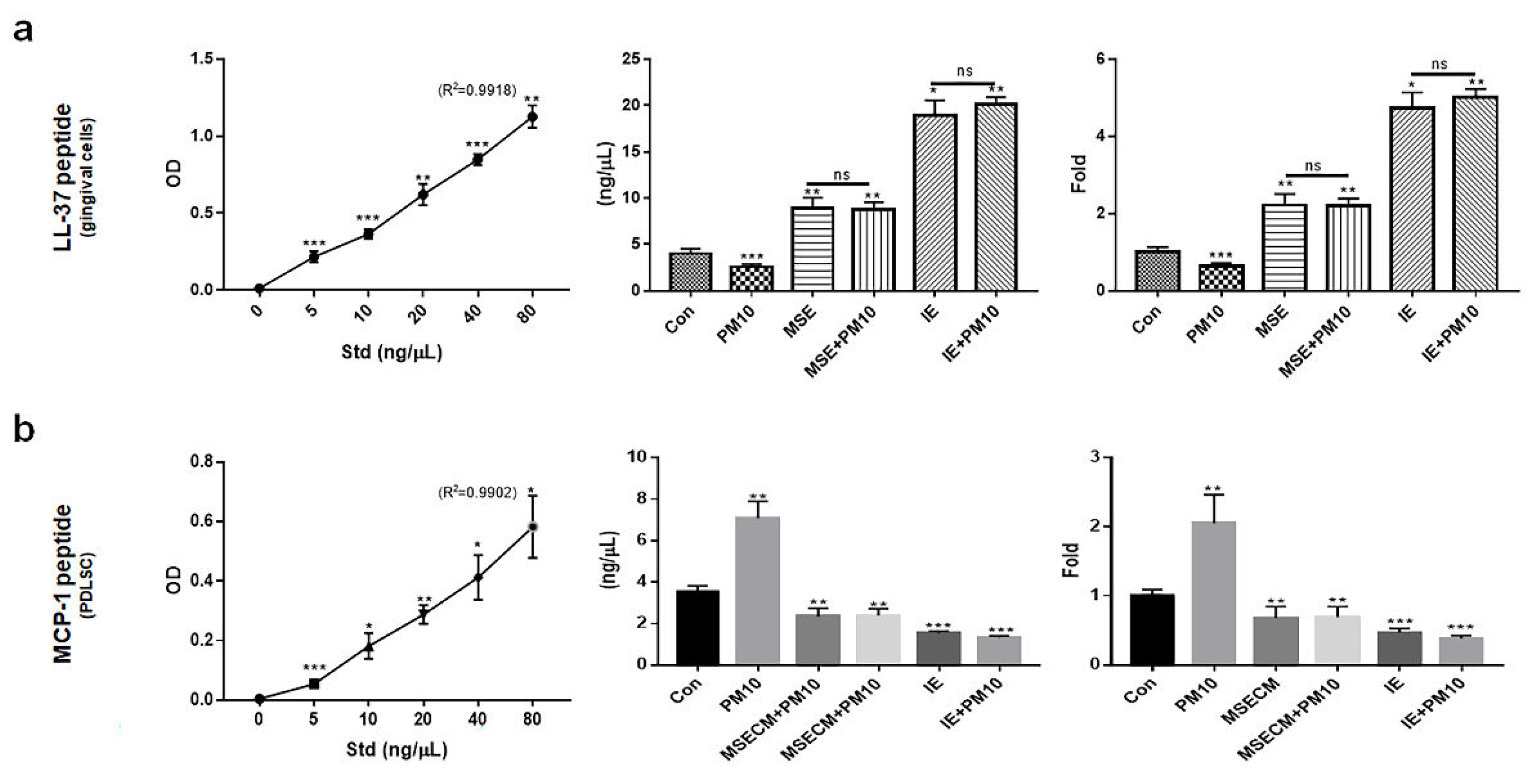

2.5. Modulation of Homeostatic Proteins By Two Bio-Materials

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Test to Establish the Treatment Dosage

4.2. Anti-Apoptotic Activity of MSE

4.3. Anti-Apoptotic Activity of IE

4.4. PDLSC Differentiation Patterns Under MSECM

4. 5. PDLSC Differentiation Patterns Under IE

4.6. Immunocytochemistry for Osteoblasts

4.7. Localization of PDLSC Markers Using Immunocytochemistry

4.8. Homeostatic Modulator Concentrations

4.9 . Statistical Analysis

|

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Shan, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Shu, Y.; Linghu, X.; Wang, B. Adverse effects of exposure to fine particles and ultrafine particles in the environment on different organs of organisms. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2024, 135, 449-473. [CrossRef]

- Combes, A.; Franchineau, G. Fine particle environmental pollution and cardiovascular diseases. Metabolism 2019, 100, 153944. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, B.; Li, S.; Chen, G.; Yang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J.; Guo, Y. Exposure to ambient particulate matter air pollution, blood pressure and hypertension in children and adolescents: a national cross-sectional study in China. Environment international 2019, 128, 103-108. [CrossRef]

- Javadinejad, S.; Dara, R.; Jafary, F. Health impacts of extreme events. Safety in Extreme Environments 2020, 2, 171-181.

- Xu, H.; Jia, Y.; Sun, Z.; Su, J.; Liu, Q.S.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, G. Environmental pollution, a hidden culprit for health issues. Eco-Environment & Health 2022, 1, 31-45. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Gangamma, S.; Raut, A.A.; Kumar, H. Particulate matter (PM10) enhances RNA virus infection through modulation of innate immune responses. Environmental Pollution 2020, 266, 115148. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Song, Y.; Pan, J. Urban particulate matter (PM) suppresses airway antibacterial defence. Respiratory research 2018, 19, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Franzetti, A.; Gandolfi, I.; Gaspari, E.; Ambrosini, R.; Bestetti, G. Seasonal variability of bacteria in fine and coarse urban air particulate matter. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2011, 90, 745-753. [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.C.; Andersen, Z.J.; Baccarelli, A.; Diver, W.R.; Gapstur, S.M.; Pope III, C.A.; Prada, D.; Samet, J.; Thurston, G.; Cohen, A. Outdoor air pollution and cancer: An overview of the current evidence and public health recommendations. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2020, 70, 460-479.

- Panagakos, F.; Scannapieco, F. Periodontal inflammation: from gingivitis to systemic disease. Gingival diseases: Their aetiology, prevention and treatment 2011, 155-168.

- Park, Y.; Shin, G.H.; Jin, G.S.; Jin, S.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.G. Effects of black jade on osteogenic differentiation of adipose derived stem cells under benzopyrene. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 1346. [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Ikemoto, T.; Morine, Y.; Imura, S.; Saito, Y.; Yamada, S.; Shimada, M. The differences in the characteristics of insulin-producing cells using human adipose-tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells from subcutaneous and visceral tissues. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 13204. [CrossRef]

- Gardin, C.; Ricci, S.; Ferroni, L. Dental stem cells (DSCs): Classification and properties. Dental Stem Cells: Regenerative Potential 2016, 1-25.

- Queiroz, A.; Albuquerque-Souza, E.; Gasparoni, L.M.; de França, B.N.; Pelissari, C.; Trierveiler, M.; Holzhausen, M. Therapeutic potential of periodontal ligament stem cells. World journal of stem cells 2021, 13, 605. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Jin, F. Periodontitis promotes the proliferation and suppresses the differentiation potential of human periodontal ligament stem cells. International journal of molecular medicine 2015, 36, 915-922. [CrossRef]

- Ridyard, K.E.; Overhage, J. The potential of human peptide LL-37 as an antimicrobial and anti-biofilm agent. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 650. [CrossRef]

- Bechinger, B.; Gorr, S.-U. Antimicrobial peptides: mechanisms of action and resistance. Journal of dental research 2017, 96, 254-260. [CrossRef]

- Aidoukovitch, A.; Anders, E.; Dahl, S.; Nebel, D.; Svensson, D.; Nilsson, B.O. The host defense peptide LL-37 is internalized by human periodontal ligament cells and prevents LPS-induced MCP-1 production. Journal of Periodontal Research 2019, 54, 662-670.

- Nilsson, B.O. Mechanisms involved in regulation of periodontal ligament cell production of pro-inflammatory cytokines: Implications in periodontitis. Journal of periodontal research 2021, 56, 249-255. [CrossRef]

- Svensson, D.; Aidoukovitch, A.; Anders, E.; Jönsson, D.; Nebel, D.; Nilsson, B.-O. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor regulates human periodontal ligament cell production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Inflammation Research 2017, 66, 823-831. [CrossRef]

- Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Communication by extracellular vesicles: where we are and where we need to go. Cell 2016, 164, 1226-1232. [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Song, S.; Chen, N.; Liao, J.; Zeng, L. Stem cell-derived exosomes: A supernova in cosmetic dermatology. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 2021, 20, 3812-3817. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, S.; Du, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chu, L.; Han, X.; Galons, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H. Exosomes from different cells: Characteristics, modifications, and therapeutic applications. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 207, 112784. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, K.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, M.W.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.G. Effects of induced exosomes from endometrial cancer cells on tumor activity in the presence of Aurea helianthus extract. Molecules 2021, 26, 2207. [CrossRef]

- Keller, N.M. The legalization of industrial hemp and what it could mean for Indiana's biofuel industry. Ind. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 2013, 23, 555.

- Johnson, R. Defining hemp: a fact sheet. Congressional Research Service 2019, 44742, 1-12.

- Fordjour, E.; Manful, C.F.; Sey, A.A.; Javed, R.; Pham, T.H.; Thomas, R.; Cheema, M. Cannabis: A multifaceted plant with endless potentials. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14, 1200269. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Bai, M.; Song, H.; Yang, L.; Zhu, D.; Liu, H. Hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa) Chemical composition and the application of hempseeds in food formulations. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2022, 77, 504-513. [CrossRef]

- Aloo, S.O.; Kwame, F.O.; Oh, D.-H. Identification of possible bioactive compounds and a comparative study on in vitro biological properties of whole hemp seed and stem. Food Bioscience 2023, 51, 102329. [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, R.; Bhuyan, S.K.; Mohanty, J.N.; Das, S.; Juliana, N.; Abu, I.F. Periodontitis and its inflammatory changes linked to various systemic diseases: a review of its underlying mechanisms. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2659. [CrossRef]

- Marruganti, C.; Shin, H.-S.; Sim, S.-J.; Grandini, S.; Laforí, A.; Romandini, M. Air pollution as a risk indicator for periodontitis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 443. [CrossRef]

- Rayad, S.; Dobrzyński, M.; Kuźniarski, A.; Styczyńska, M.; Diakowska, D.; Gedrange, T.; Klimas, S.; Gębarowski, T.; Dominiak, M. An In-Vitro Evaluation of Toxic Metals Concentration in the Third Molars from Residents of the Legnica-Głogów Copper Area and Risk Factors Determining the Accumulation of Those Metals: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 2904. [CrossRef]

- Cocârţă, D.M.; Prodana, M.; Demetrescu, I.; Lungu, P.E.M.; Didilescu, A.C. Indoor air pollution with fine particles and implications for workers’ health in dental offices: A brief review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 599. [CrossRef]

- Merzouki, A. Cheikh Yebouk, Fatima Zahrae Redouan, Ahmedou Soulé, and. 2024.

- Alves, L.; Machado, V.; Botelho, J.; Mendes, J.J.; Cabral, J.M.; da Silva, C.L.; Carvalho, M.S. Enhanced proliferative and osteogenic potential of periodontal ligament stromal cells. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1352. [CrossRef]

- Mohebichamkhorami, F.; Fattahi, R.; Niknam, Z.; Aliashrafi, M.; Khakpour Naeimi, S.; Gilanchi, S.; Zali, H. Periodontal ligament stem cells as a promising therapeutic target for neural damage. Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2022, 13, 273. [CrossRef]

- Marchesan, J.T.; Scanlon, C.S.; Soehren, S.; Matsuo, M.; Kapila, Y.L. Implications of cultured periodontal ligament cells for the clinical and experimental setting: a review. Archives of oral biology 2011, 56, 933-943. [CrossRef]

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J.; Mombelli, A. The therapy of peri-implantitis: a systematic review. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants 2014, 29.

- Tuikampee, S.; Chaijareenont, P.; Rungsiyakull, P.; Yavirach, A. Titanium Surface Modification Techniques to Enhance Osteoblasts and Bone Formation for Dental Implants: A Narrative Review on Current Advances. Metals 2024, 14, 515. [CrossRef]

- Grawish, M.E.; Saeed, M.A.; Sultan, N.; Scheven, B.A. Therapeutic applications of dental pulp stem cells in regenerating dental, periodontal and oral-related structures. World Journal of Meta-Analysis 2021, 9, 176-192. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Abbott, P.V. An overview of the dental pulp: its functions and responses to injury. Australian dental journal 2007, 52, S4-S6. [CrossRef]

- Tokajuk, J.; Deptuła, P.; Piktel, E.; Daniluk, T.; Chmielewska, S.; Wollny, T.; Wolak, P.; Fiedoruk, K.; Bucki, R. Cathelicidin LL-37 in health and diseases of the oral cavity. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1086. [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, D.; Nilsson, B.O. The antimicrobial peptide LL-37 is anti-inflammatory and proapoptotic in human periodontal ligament cells. Journal of periodontal research 2012, 47, 330-335. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Anshita, D.; Ravichandiran, V. MCP-1: Function, regulation, and involvement in disease. International immunopharmacology 2021, 101, 107598.

- Fernández-Rojas, B.; Gutiérrez-Venegas, G. Flavonoids exert multiple periodontic benefits including anti-inflammatory, periodontal ligament-supporting, and alveolar bone-preserving effects. Life sciences 2018, 209, 435-454. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).