Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting and Samples

3. Analytical Methods

3.1. Whole-Rock Major and Trace Element

3.2. Zircon LA-ICP-MS U-Pb Dating

3.3. Whole-Rock Sr-Nd Isotopes and Zircon Lu-Hf Isotopes

4. Analytical Results

4.1. Chronological Characteristics

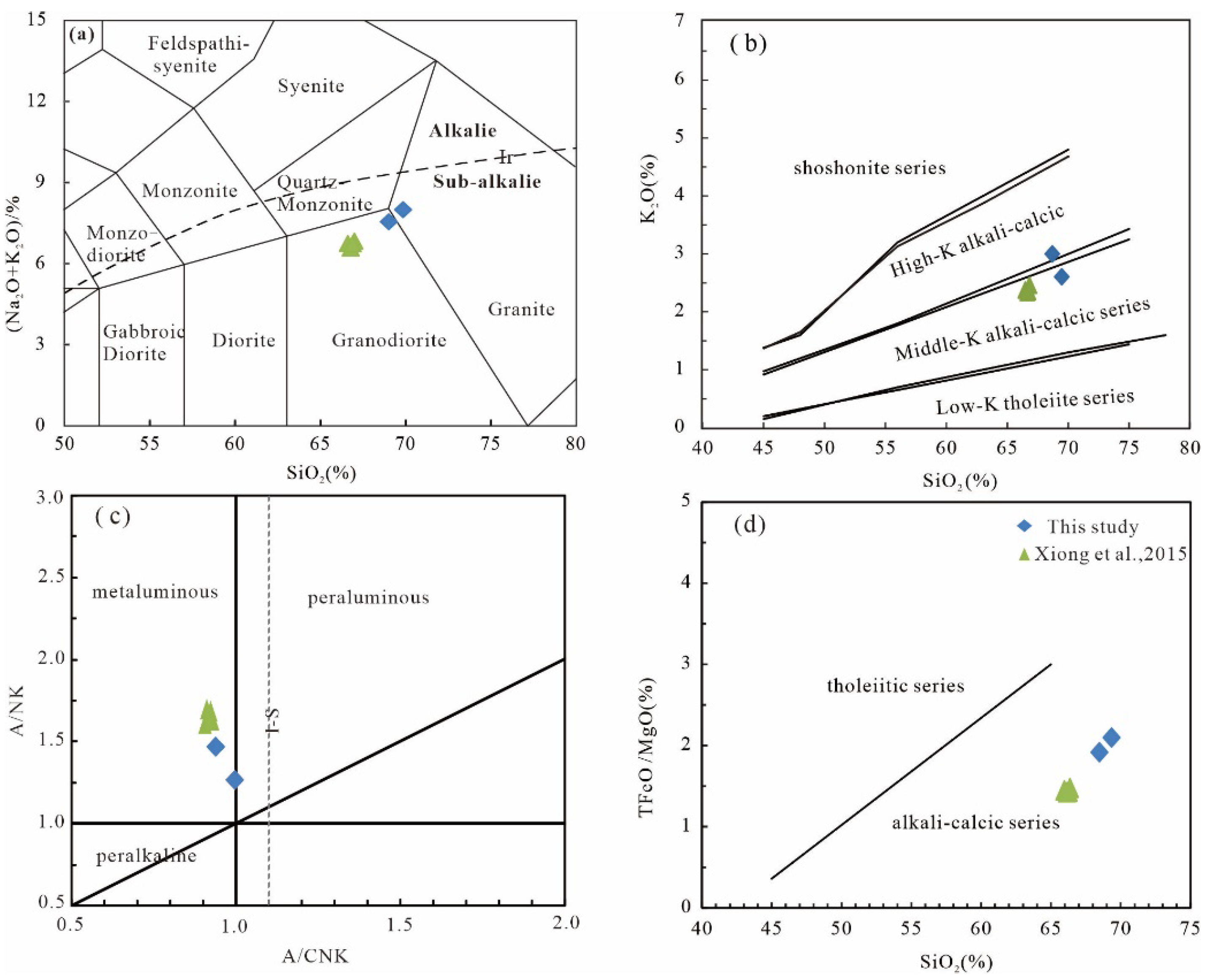

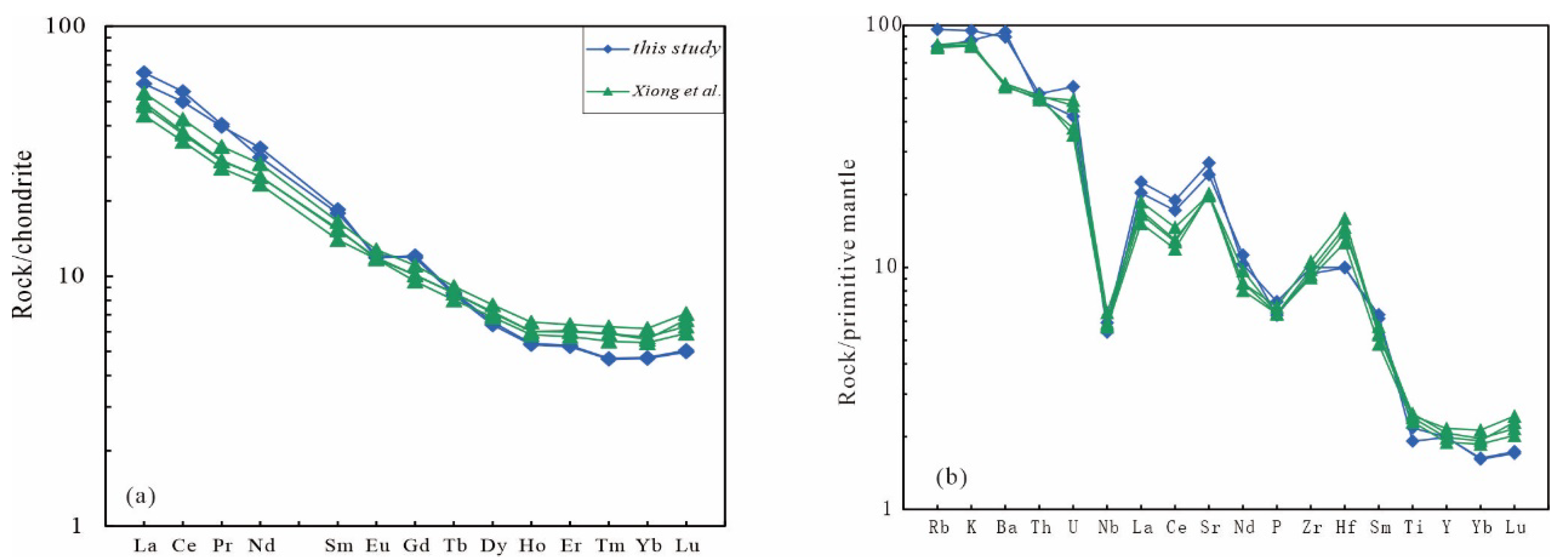

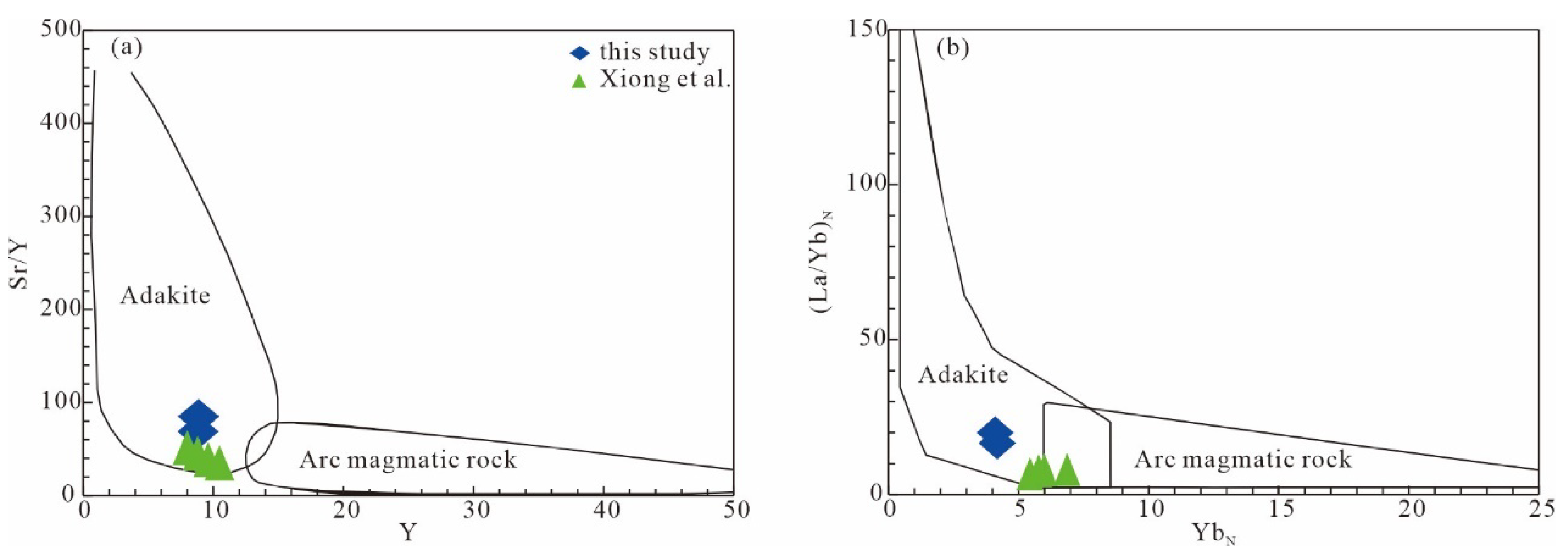

4.2. Major and Trace Elements

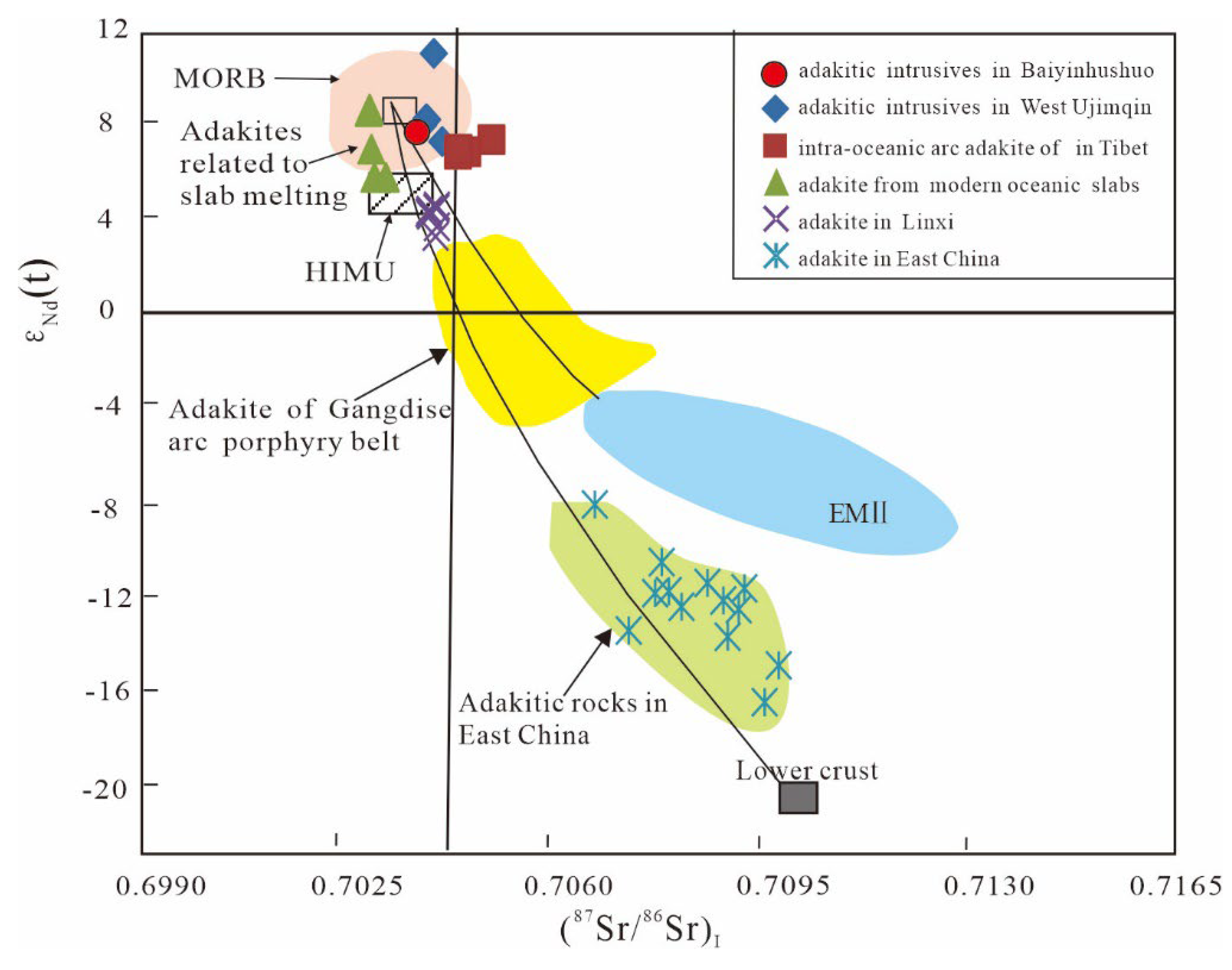

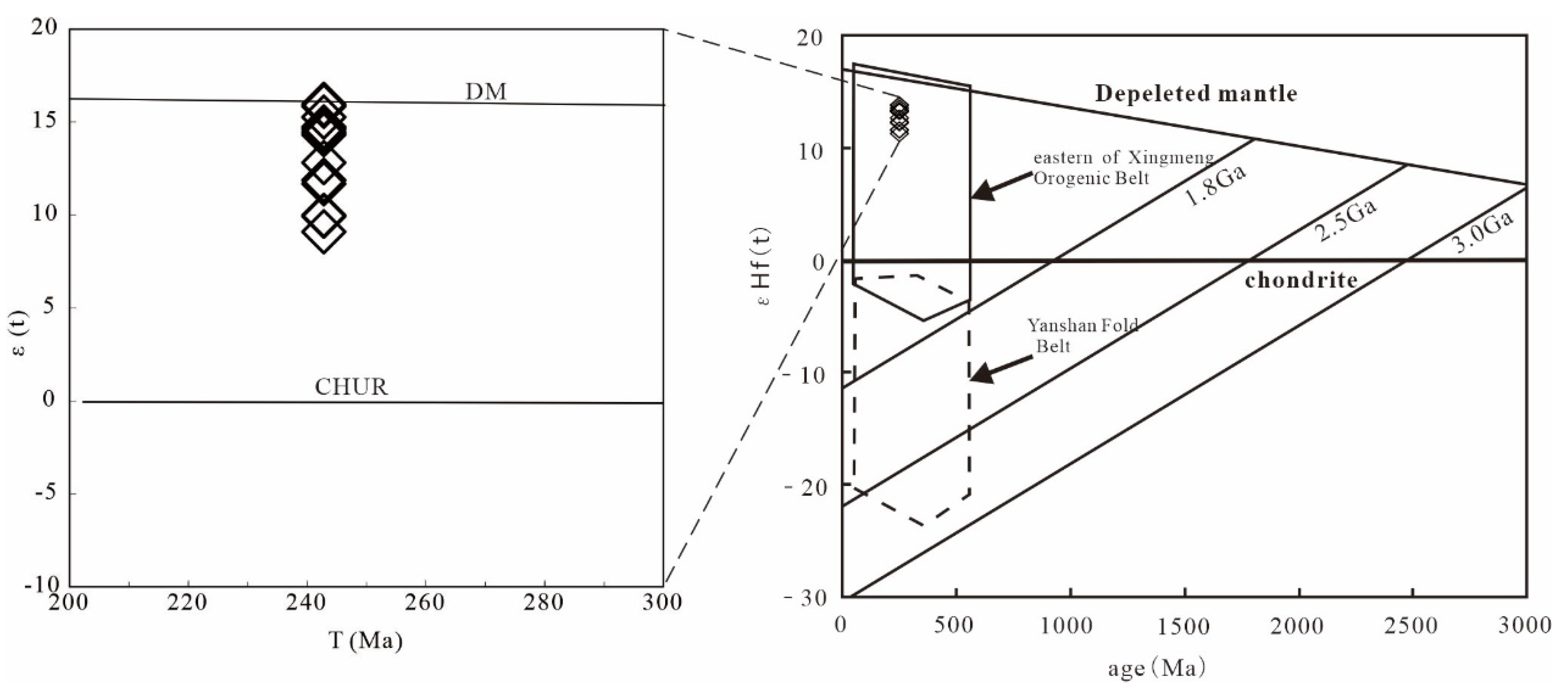

4.3. Isotope Geochemical Characterization

5. Discussion

5.1. Chronology

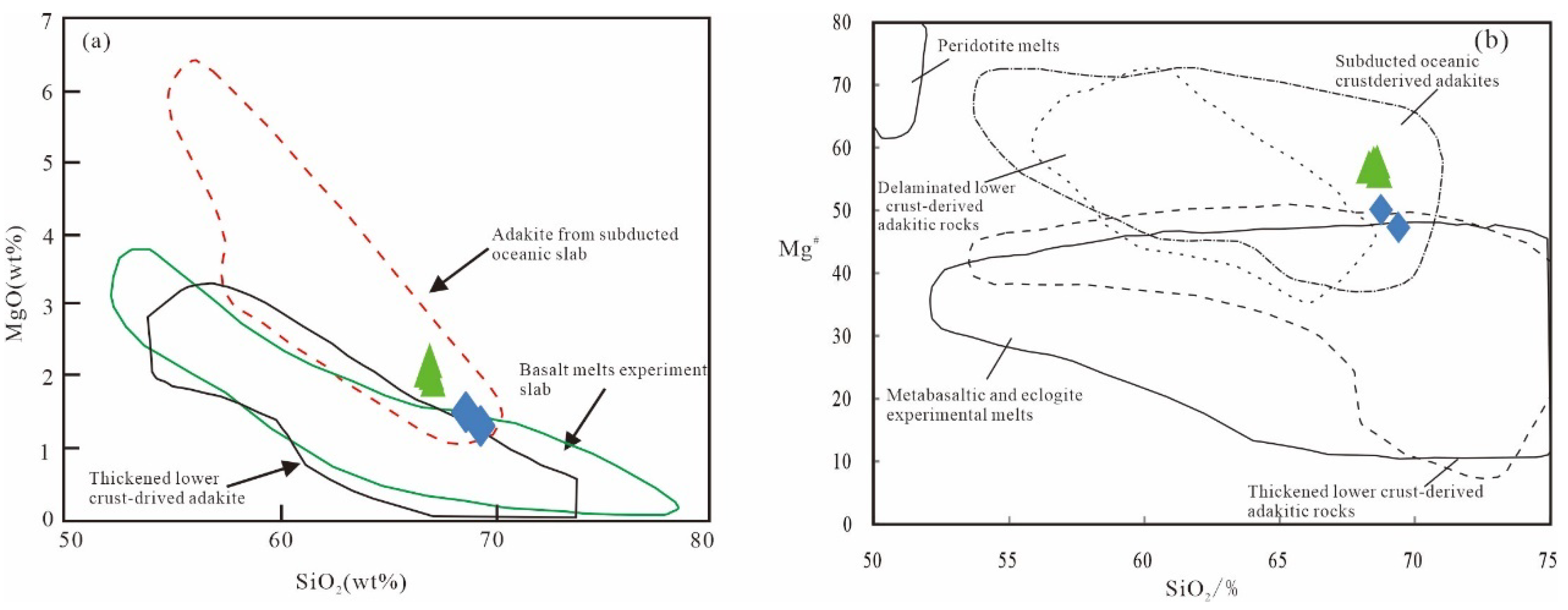

5.2. Petrogenesis of Adakite

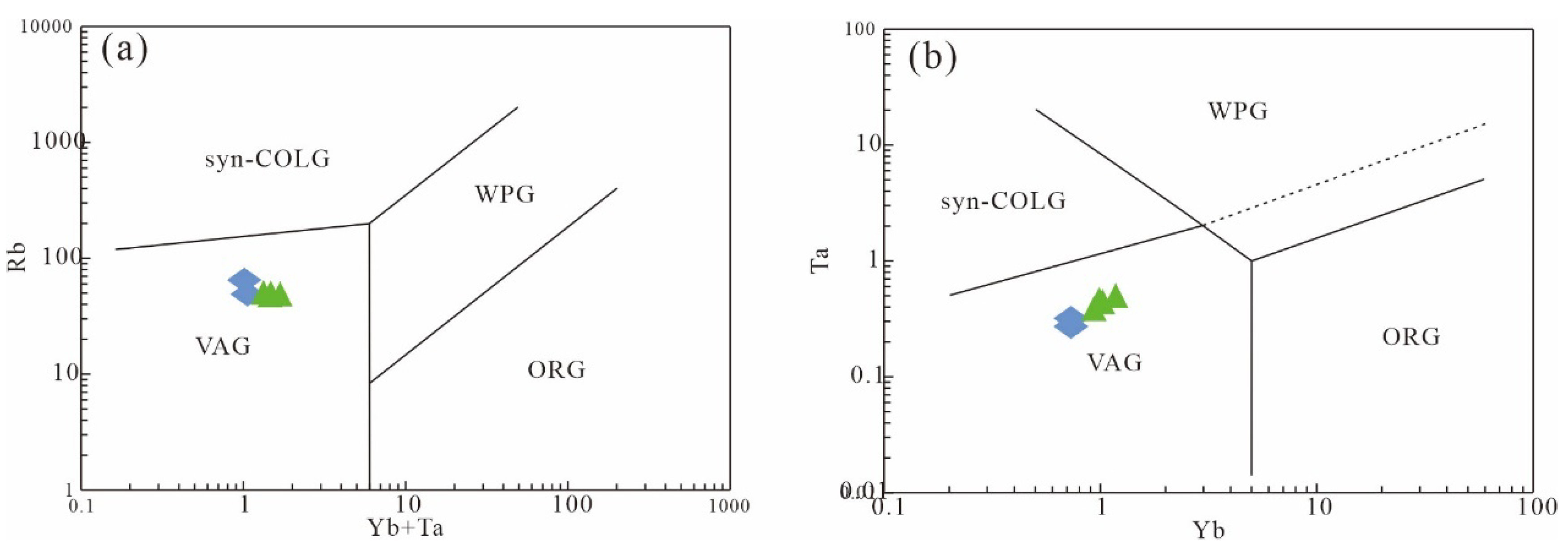

5.3. Tectonic Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sengör, A.M.C. . Natalin.B.A.. Burtman. V.S..1993. Evolu-tion of the Altaid Tectonic Collage and Paleozoic Crus-tal Growth in Eurasia. Nature,364 :299-307. [CrossRef]

- Sengör A M C, Natal'In B A. Turkic-type orogeny and its role in the making of the continental crust. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 1996, 24(1): 263-337. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J. , Brian F. Windley, Hao, J., Zhai. M.G., 2003. Accretion leading to collision and the Permian Solonker suture, Inner Mongolia, China: Termination of the central Asian orogenic belt. Tectonics 22(6):n/a-n/a. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J. , Windley, B.F., Han, C.M., Liu, W., Wan, B., Zhang, J.E., Ao, S.J., Zhang, Z.Y., Song, D.F. 2018. Late Paleozoic to Early Triassic multiple roll-back and oroclinal bending of the Mongolia collage in Central Asia. Earth-Science Reviews, 186: 94-128. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W. J, Song, D.F., Windley, B.F., Li, J.L., Han, C.M., Wan, B., Zhang, J.E., Ao, S.J. Zhang, Z.Y. 2020. Accretionary processes and metallogenesis of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Advances and perspectives. Science China (Earth Sciences), 63(3): 329-361. [CrossRef]

- Windley B F, Alexeiev D, Xiao W J, Kröner A, Badarch G. 2007.Tectonic models for accretion of the central Asian orogenic belt. J Geol Soc, 164: 31–47. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F. , Chi X.G., Zhan Z., Hu Z.C. and Chen J.Q. 2013. Zircon U-Pb age and petrologenetic discussion on Jianshetun adakite in Balinyouqi, Inner Mongolia. Aeta Petrologica Sinica,29(3): 827 -839 (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Liu, J.F. , Li J.Y., Chi X.C., Qu J.F., Hu Z.C. and Guo C.L. 2014. Petrological and geochemical characteristics of the Karly 'Triassic granite belt in southeastern Inner Mongolia and its tectonic setting. Acta Ceologioa Sinica,88(9): 1677 -1690 (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Liu, J.F. , Li, J.Y., Chi, X.G., Qu, J.F., Chen, J.Q., Hu, Z., and Feng, Q.W. 2016. The tectonic setting of early Permian bimodal volcanism in central Inner Mongolia: Continental rift, post-collisional extension, or active continental margin? International Geology Review, 58(6): 737–755. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F. , Li J.Y., Zhao S., Zhang J., Zheng R.G., Zhang W.L., Lv Q.L., Zheng P.X. 2022. Crustal accretion and Paleo-Asian Ocean evolution during Late Paleozoic-Early Mesozoic in southeastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Evidence from magmatism in Linxi-Dongwuqi area, southeastern Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 38(8): 2181-2215. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J. , Wang, J.F., Li, H.Y.; et al., 2012. Recognition of Diyanmiao Ophiolite in Xi Ujimqin Banner, Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 28(4):1282-1290(in Chinese with English abstract).

- Li, Y.J. , Wang, J.F., Wang, G.H., Li, H.Y., Dong, P.P., 2018. Discovery and significance of the Dahate fore-arc basalts from Diyanmiao ophiolite in Inner Mongolia. Acta Petrobgica Sinica, 34 (02):469-482.

- Cheng, Y. , Xiao, Q.H., Li, T.D.; et al., 2019. Magmatism and Tectonic Background of the Early Permian Intra-Oceanic Arc in the Diyanmiao Subduction Accretion Complex Belt on the Eastern Margin of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Science China:Earth Sciences, 44(10):3454-3468(in Chinese with English abstract).

- Li, S. , Chung S. L., Wilde S. A., Jahn B. M., Xiao W. J., Wang T, Guo Q. Q. 2017. Early-Middle Triassic high Sr/Y granitoids in the southern Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Implications for ocean closure in accretionary orogens. Geophys Res Solid Earth, 122: 2291–2309. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.Q. , Liu, M., Zhao, H.T., Zhang, D., Wang, H.R., Wang, Z., Hu, X.C. 2015. Zircon U-Pb.LA-ICP-MS dating, geochemical, Hf isolopic characteristics of Bayanhushu granodiorite in West Ujimqin banner and geological significance. Geological Review.G1(3): 651 -663. (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Fan, Y.X. , Li, T.D., Xiao, Q.H., Cheng, Y., Li Y., Guo, L.J., Luo, P.Y. 2019. Zircon U-Pb ages, geochemical characteristics of Late Permian granite in West Ujimqin Banner, Inner Mongolia, and tectonic significance. Geological Review, 65(1); 248 -266 (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Li, S.C. , Wang, H.T., Li, G., Wang, X.A., Yang, X.P., Zhao, Z.R. 2020. Northward plate subduction process of the Paleo-Asian Ocean in the middle part of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Evidence from adakites. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 36( 8) : 2521-2536. [CrossRef]

- Li, S. , Chung, S. L., Wilde, S.A., Wang, T., Xiao, W.J., Guo, Q.Q. 2016. Linking magmatism with collision in an accretionary orogen. Sci Rep, 6: 25751. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.D. , Li, S., Chew, D., Liu, T.Y., Guo, D.H. 2021. Permian-Triassic magmatic evolution of granitoids from the southeastern Central Asian Orogenic Belt: Implications for accretion leading to collision. Science China Earth Sciences, 64(5): 788–806. [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.C. , Zhang, F., Fan, W.M., and Liu, D.Y. 2007. Phanerozoic evolution of the Inner Mongolia–Daxinganling orogenic belt in North China: Constraints from geochronology of ophiolites and associated formations. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 280(1): 223–237. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F. , Li, Y.J., Li, H.J., and Dong, P.P. 2017. Discovery of Early Permian Intra-oceanic arc adakite in the Meilaotewula Ophiolite, Inner Mongolia and its evolution model. Acta Geologica Sinica, 91(8): 1776–1795.

- Liu, Y.S. , Hu Z.C., Gao S., Günther D., Xu J., Gao C.G. and Chen H.H., 2008. In situ analysis of major and trace elements of anhydrous minerals by LA-ICP-MS without applying an internal standard. Chem. Geol., 257(1-2): 34-43. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig.K.R. 2003. Users Manual for Isoplot 3.00; A Geo-chronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel. Berkeley Ge-ochronolog y Center, Special Publication,4:1-71.

- Hou, K.J. , Li Y.H., Zou T.R., Qu X.M., Shi Y.R., Xie G.Q. 2007. Laser ablation-MC-ICP-MS technique for Hf isotope microanalysis of zircon and its geological applications. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 23(10): 2595-2604.

- Scherer, E. , Munker, C., Mezger, K., 2001. Calibration of the lutetium-hafnium clock. Science, 293 (5530):683-687. [CrossRef]

- Blichert-Toft, J. , Albarède, F., 1997. The Lu-Hf Isotope Geochemistry of Chondrites and the Evolution of the Mantle-Crust System. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 148(1/2):243-258. [CrossRef]

- Corfu, F. , Hanchar, J.M., Hoskin, P.W.O.; et al., 2003. Atlas of Zircon Textures. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 53(1):469-500. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. B. , Zheng, Y. F., 2004. Genesis of Zircon and its Constraints on Interpretation of U-Pb Age. Chinese Science Bulletin, 49(15):1554-1569(in Chinese with English abstract). [CrossRef]

- Middlemost, Eric.A.K., 1994. Naming materials in the magma/igneous rock system. Earth-Science Reviews, 37 (3):215-224. [CrossRef]

- Maniar, P.D. , Piccoli, P.M., 1989. Tectonic discrimination of granitoids. GSA Bull, 101: 635-643.

- Peccerillo, A.; Taylor, S.R. Geochemistry of eocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks from the Kastamonu area, Northern Turkey. Contrib. Fan Miner. Petrol. 1976, 58, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashiro, A. . 1974. Volcanic rock series in island arcs and active continental margins. American Journal of Science, 274: 321–355. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.S. , McDonough, W.E.. 1989. Chemical and Isotopic Systematics of Oceanic Basalts: Implications for Mantle Composition and Processes. In: Saunders, A.D., Norry, M.J., eds., Magmatism in the Ocean Basins, Geological Society of London, Specialcation, London, 313-345.

- Wu, F.Y. , Li, X.H., Zheng, Y.F.; et al., 2007. Lu-Hf Isotopic Systematics and their Applications in Petrology. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 23(2):185-220(in Chinese with English abstract) ttp://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=perio&id=ysxb98200702001.

- Bao, Q.Z. , Zhang, C.J., Wu, Z.L., Wang H., Li W., Sang J.H.. 2007. SHRIMP U-Pb Zircon Geochronology of a Carboniferous Quartz-Diorite in Baiyingaole Area, Inner Mongolia and Its Implications. Journal of Jilin University (Earth Science Edition), 37(1):15-23(in Chinese with English abstract).

- Guo, Z.J. , Zhou Z.H., Li G.T., Li J.W., Wu X.L., Ouyang H.G., Wang A.S., Xiang A.P., Dong X.Z.. 2012. SHRIMP U-Pb zircon dating and petrogeochemistral characteristics of the intermediate-acid intrusive rocks in the Aoergai copper deposit of Inner Mongolia. Geology in China,39(6):1486 -1500 (in Chinese with English abstract).

- Defant M, J. , Drummond M S.1990. Derivation of some modern arc magmas by melting of young subducted lithosphere. Nature 347:662. [CrossRef]

- Rapp, R. P. Shimizu, M. D. Norman, G. S. Applegate.1999. Reaction between slab-derived melts and peridotite in the mantle wedge: Experimental constraints at 3.8 GPa. Chemical Geology 160(4):335-356. [CrossRef]

- Martin, H. , Smithies, R.H., Rapp, R., Moyen, J.F. 2005. An overview of adakite, tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite (TTG),and sanukitoid: Relationships and some implications for crustal evolution. Lithos, 79(1/2):1-24. [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.B. , 1995. Genesis of High Mg# Andesites and the Continental Crust. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 120(1): 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. , Jahn, B.M., Wilde, S.A., and Xu, B. 2000. Two contrasting Paleozoic magmatic belts in northern Inner Mongolia, China: Petrogenesis and tectonic implications. Tectonophysics, 328(1–2): 157–182. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. , Xu, J.F., Jian, P., Bao, Z.W., Zhao, Z.H., Li, C.F.; et al. 2006. Petrogenesis of adakitic porphyries in an extensional tectonic setting, Dexing, South China: Implications for the genesis of porphyry copper mineralization. Journal of Petrology, 47: 119–144. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. , Wang Y., Qian Q., Yang J.H., Wang Y.L., Zhao T.P., Guo G.J. 2001. The characteristics and tectonic-metallogenic significances of the adakites in Yanshanian period from eastern China. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 17( 2): 236- 244.

- Luo, H.L. , Wu T.R., Li Y. 2007&. Geochemistry and SHRIMP dating of the Kebu massif from Wulatezhongqi, Inner Mongolia: Evidence for the Early Permian underplating beneath the North China Craton. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 23(4):755~766.

- Xiong, X.L. , Liu X.C., Zhu Z.M., Li Y., Xiao W.S., Song M.S., Zhang S., Wu J.H. 2011. Adakitic rocks and destruction of the North China Craton: Evidence from experimental petrology and geochemistry. Science China (Earth Science), 54: 858-870. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. B. , Liu, Y. S., Zong, K. Q.; et al., 2009. Early Mesozoic O-Type High-Mg Adakitic Andesites from Linxi Area, Inner Mongolia and Its Implication. Geological Science and Technology Information, 28(6): 31-38(in Chinese with English abstract). http://www.en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-DZKQ200906005.htm.

- Pearce J A, Harris N B W, Tindle A G.1984.Trace element discrimination diagrams for the tectonic interpretation of granitic rocks. Journal of Petrology, 25(4):956~983. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.H. , Wang, Q., Xiong, X.L.; et al., 2006. Two-Types of Adakites in North Xinjiang China. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 22(5):1249-1265(in Chinese with English abstract).

- Hou, Z.Q. , Pan, X.F., Yang, Z.M.; et al., 2007.Porphyry Cu Mo-Au)Deposits no Related to Oceanic-Slab Subduction:Examples from Chinese Porphyry Deposits in Continental Settings.Geoscience, 21(2):332-351(in Chinese with English abstract).

- Wei, D. L. , Xia, B., Zhou, G. Q.; et al., 2007. Geochemistry and Sr-Nd Isotope Characteristics of Tonalites in Zêtang, Tibet:New Evidence for Intra-Tethyan Subduction. Science in China Series D: Earth Sciences, 50(6):836-846(in Chinese). [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z. Q. , Gao, Y. F., Qu, X. M.; et al., 2004. Origin of Adakitic Intrusives Generated during Mid-Miocene East-West Extension in Southern Tibet. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 220(1/2):139-155. [CrossRef]

- Falloon, T.J. , Danyushevsky, L.V., Crawford, A.J., Meffre, S., Woodhead, J.D.,Bloomer, S.H., and 49(4): 697–715. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B., Kimura, J.I., Machida, S., Ishii, T., Ishiwatari, A., Maruyama, S.; et al.2013. High-Mg adakite and low-Ca boninite from a bonin fore-arc seamount: Implications for the reaction between slab melts and depleted mantle. Journal of Petrology, 54(6): 1149–1175. [CrossRef]

- Amelin, Y. , Lee, D. C., Halliday, A. N.; et al., 1999. Nature of the Earth's Earliest Crust from Hafnium Isotopes in Single Detrital Zircons. Nature, 399(6733):252-255. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H. , Wu F.Y., Shao J., Wilde S. A., Xie L.W., Liu X.M. 2006. Constraints on the timing of uplift of the Yanshan Fold and Thrust Belt, North China. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 246(3):336~352. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.J. , Liu S.W., Ren J.S., Wang Y. 1997. Later Permian-early Trissic sedimentary evolution and tectonic setting of Linxi region Inner Mongolia.Regional Geology of China,16(4):403~409.

- Liu, W. , Pan X.F., Xie L.W., Li H. 2007. Sources of material for the Linxi granitoids, the southern segment of the Da Hinggan Mts.: When and how continental crust grew?.Acta Petrologica Sinica, 23(2):441-460.

- Shao, J.A. , Hong D.W., Zhang L.Q. 2002: Genesis of Sr-Nd isotopic characteristics of igneous rocks in Inner Mongolia. Geological Bulletin of China, 21(12): 817-822.

- Zhang, X.H. , Zhang H.F., Tang Y.J., Liu J.M. 2006. Early Triassic A-type felsic volcanism in the Xilinhaote-Xiwuqi, central Inner Mongolia: Age, geochemistry and tectonic implications. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 22(11): 2769-2780.

| spot | Pb | Th | U | isotope ratio | age | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 207Pb/206Pb | 207Pb/235U | 206Pb/238U | 207Pb/206Pb | 207Pb/235U | 206Pb/238U | ||||||||||

| HS17-05-1 | 9.20 | 81.59 | 196.24 | 0.0549 | 0.0065 | 0.2612 | 0.0243 | 0.0371 | 0.0009 | 409.3 | 265.6 | 235.6 | 19.5 | 234.7 | 5.8 |

| HS17-05-2 | 10.81 | 96.49 | 215.68 | 0.0516 | 0.0057 | 0.2746 | 0.0281 | 0.0390 | 0.0009 | 264.9 | 237.0 | 246.3 | 22.4 | 246.6 | 5.6 |

| HS17-05-3 | 11.54 | 105.51 | 266.05 | 0.0514 | 0.0056 | 0.2749 | 0.0320 | 0.0390 | 0.0009 | 257.5 | 242.6 | 246.6 | 25.5 | 246.5 | 5.8 |

| HS17-05-7 | 17.52 | 210.71 | 323.19 | 0.0523 | 0.0048 | 0.2818 | 0.0251 | 0.0397 | 0.0010 | 298.2 | 211.1 | 252.1 | 19.9 | 250.9 | 6.2 |

| HS17-05-9 | 12.65 | 117.88 | 238.69 | 0.0500 | 0.0050 | 0.2885 | 0.0265 | 0.0410 | 0.0010 | 194.5 | 218.5 | 257.4 | 20.9 | 259.0 | 6.1 |

| HS17-05-10 | 9.89 | 104.35 | 215.33 | 0.0542 | 0.0049 | 0.2753 | 0.0232 | 0.0374 | 0.0012 | 388.9 | 203.7 | 246.9 | 18.5 | 236.5 | 7.3 |

| HS17-05-11 | 8.67 | 65.99 | 168.49 | 0.0558 | 0.0061 | 0.3106 | 0.0286 | 0.0428 | 0.0012 | 442.6 | 272.2 | 274.7 | 22.1 | 270.5 | 7.5 |

| HS17-05-12 | 25.16 | 298.49 | 488.14 | 0.0505 | 0.0033 | 0.2698 | 0.0175 | 0.0386 | 0.0008 | 220.4 | 153.7 | 242.6 | 14.0 | 244.1 | 4.7 |

| HS17-05-13 | 17.12 | 185.40 | 334.21 | 0.0505 | 0.0038 | 0.2696 | 0.0203 | 0.0384 | 0.0008 | 220.4 | 177.8 | 242.4 | 16.2 | 243.2 | 5.1 |

| HS17-05-14 | 12.17 | 111.35 | 258.52 | 0.0510 | 0.0048 | 0.2702 | 0.0230 | 0.0386 | 0.0008 | 242.7 | 216.6 | 242.9 | 18.4 | 244.5 | 4.9 |

| HS17-05-15 | 12.50 | 103.26 | 267.82 | 0.0523 | 0.0045 | 0.3101 | 0.0255 | 0.0431 | 0.0011 | 301.9 | 191.6 | 274.3 | 19.8 | 272.0 | 6.5 |

| HS17-05-17 | 33.82 | 553.50 | 483.04 | 0.0523 | 0.0034 | 0.2844 | 0.0168 | 0.0402 | 0.0008 | 298.2 | 150.0 | 254.1 | 13.3 | 254.1 | 5.0 |

| HS17-05-18 | 22.37 | 227.49 | 442.93 | 0.0526 | 0.0034 | 0.2846 | 0.0181 | 0.0388 | 0.0008 | 309.3 | 148.1 | 254.3 | 14.3 | 245.5 | 4.7 |

| HS17-05-20 | 10.94 | 104.53 | 223.74 | 0.0547 | 0.0054 | 0.2843 | 0.0259 | 0.0389 | 0.0010 | 466.7 | 222.2 | 254.1 | 20.5 | 245.9 | 6.0 |

| HS17-05-21 | 24.59 | 317.06 | 463.84 | 0.0511 | 0.0034 | 0.2593 | 0.0167 | 0.0371 | 0.0008 | 242.7 | 153.7 | 234.1 | 13.5 | 234.8 | 5.0 |

| HS17-05-22 | 16.22 | 186.03 | 314.59 | 0.0507 | 0.0045 | 0.2674 | 0.0226 | 0.0382 | 0.0008 | 227.8 | 207.4 | 240.6 | 18.1 | 241.6 | 4.8 |

| HS17-05-23 | 36.25 | 408.73 | 719.38 | 0.0521 | 0.0030 | 0.2739 | 0.0163 | 0.0381 | 0.0007 | 287.1 | 133.3 | 245.8 | 13.0 | 241.2 | 4.6 |

| HS17-05-24 | 26.68 | 234.30 | 617.82 | 0.0497 | 0.0035 | 0.2586 | 0.0176 | 0.0377 | 0.0007 | 189.0 | 167.6 | 233.5 | 14.2 | 238.6 | 4.6 |

| HS17-05-25 | 22.14 | 269.19 | 451.68 | 0.0507 | 0.0038 | 0.2629 | 0.0198 | 0.0375 | 0.0008 | 227.8 | 175.9 | 237.0 | 15.9 | 237.1 | 4.8 |

| Sample | SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | FeO | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | P2O5 | LOI | TATOL | Mg# | A/CNK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS17-05 | 69.40 | 0.48 | 15.43 | 3.07 | / | 0.05 | 1.35 | 1.92 | 5.45 | 2.67 | 0.16 | 1.39 | 99.29 | 46.73 | 1.01 |

| HS17-09 | 68.76 | 0.43 | 15.37 | 3.24 | / | 0.06 | 1.55 | 2.90 | 4.60 | 2.95 | 0.14 | 2.2 | 99.06 | 48.87 | 0.96 |

| DW11-b1* | 67.06 | 0.54 | 15.13 | 1.84 | 1.58 | 0.04 | 2.27 | 3.4 | 4.35 | 2.47 | 0.15 | 0.82 | 98.83 | 61.78 | 0.95 |

| DW11-43* | 66.93 | 0.53 | 15.48 | 1.76 | 1.49 | 0.03 | 2.12 | 3.52 | 4.45 | 2.5 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 98.95 | 61.55 | 0.94 |

| DW11-4* | 67.22 | 0.5 | 15.53 | 1.38 | 1.71 | 0.03 | 2 | 3.45 | 4.46 | 2.56 | 0.14 | 0.98 | 98.98 | 56.82 | 0.95 |

| DW11-6* | 67.15 | 0.52 | 15.4 | 1.68 | 1.51 | 0.03 | 2.11 | 3.47 | 4.46 | 2.48 | 0.14 | 0.92 | 98.95 | 61.12 | 0.94 |

| Sample | Rb | Ba | Th | U | Nb | Sr | Nd | Zr | Hf | Yb | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Sm |

| HS17-05 | 52 | 657.55 | 4.17 | 0.88 | 4.21 | 570.14 | 13.96 | 112 | 3.09 | 0.80 | 15.47 | 33.55 | 3.85 | 13.96 | 2.73 |

| HS17-09 | 61 | 625.28 | 4.44 | 1.17 | 3.86 | 509.54 | 15.23 | 105 | 3.08 | 0.80 | 13.96 | 30.53 | 3.77 | 15.23 | 2.83 |

| DW11-b1 | 52.5 | 401.4 | 4.35 | 0.98 | 4.65 | 416.6 | 11.67 | 118.5 | 4.92 | 0.97 | 11.75 | 23.1 | 2.76 | 11.67 | 2.37 |

| DW11-43 | 51.9 | 399.7 | 4.36 | 0.74 | 4.22 | 421.1 | 13.15 | 104.6 | 4.31 | 1.05 | 12.83 | 25.99 | 3.14 | 13.15 | 2.53 |

| DW11-4 | 52.9 | 388.5 | 4.28 | 1.03 | 4.05 | 425.7 | 10.89 | 101.5 | 3.91 | 0.92 | 10.44 | 21.18 | 2.57 | 10.89 | 2.14 |

| DW11-6 | 51.3 | 393.3 | 4.2 | 0.79 | 4.15 | 424 | 11.69 | 109.7 | 4.53 | 0.95 | 11.39 | 22.67 | 2.74 | 11.69 | 2.34 |

| Sample | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | Y | ΣREE | LREE/HREE | LaN/YbN | δEu | |

| HS17-05 | 0.70 | 2.43 | 0.32 | 1.62 | 0.30 | 0.86 | 0.12 | 0.80 | 0.13 | 9.06 | 76.84 | 10.68 | 13.93 | 0.83 | |

| HS17-09 | 0.69 | 2.48 | 0.32 | 1.66 | 0.30 | 0.87 | 0.12 | 0.80 | 0.13 | 9.04 | 73.71 | 10.00 | 12.47 | 0.79 | |

| DW11-b1 | 0.68 | 2.08 | 0.32 | 1.83 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.15 | 0.97 | 0.16 | 9.42 | 59.17 | 7.65 | 8.69 | 0.94 | |

| DW11-43 | 0.74 | 2.27 | 0.34 | 1.95 | 0.37 | 1.06 | 0.16 | 1.05 | 0.18 | 9.84 | 65.76 | 7.91 | 8.76 | 0.94 | |

| DW11-4 | 0.68 | 1.96 | 0.3 | 1.74 | 0.33 | 0.95 | 0.14 | 0.92 | 0.15 | 8.64 | 54.39 | 7.38 | 8.14 | 1.02 | |

| DW11-6 | 0.69 | 2.07 | 0.32 | 1.81 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.95 | 0.17 | 9.03 | 58.33 | 7.57 | 8.60 | 0.96 |

| Spot | t(Ma) | 176Yb/177Hf | 2σ | 176Lu/177Hf | 2σ | 176Hf/177Hf | 2σ | εHf(0) | εHf(t) | TDM(Ma) | T2DM(Ma) | f(Lu/Hf)s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS17-05-10 | 242.8 | 0.012445 | 0.000207 | 0.000465 | 0.000006 | 0.283006 | 0.000017 | 8.28 | 13.5 | 343 | 405 | -0.99 |

| HS17-05-10 (2) | 242.8 | 0.020651 | 0.000135 | 0.000779 | 0.000007 | 0.282970 | 0.000020 | 7.00 | 12.2 | 397 | 491 | -0.98 |

| HS17-05-11 | 242.8 | 0.022239 | 0.000562 | 0.000871 | 0.000018 | 0.282982 | 0.000015 | 7.44 | 12.6 | 381 | 464 | -0.97 |

| HS17-05-13 | 242.8 | 0.022755 | 0.000505 | 0.000914 | 0.000021 | 0.283014 | 0.000016 | 8.57 | 13.8 | 336 | 391 | -0.97 |

| HS17-05-14 | 242.8 | 0.011469 | 0.000265 | 0.000470 | 0.000012 | 0.282996 | 0.000016 | 7.93 | 13.2 | 357 | 428 | -0.99 |

| HS17-05-15 | 242.8 | 0.019129 | 0.000328 | 0.000722 | 0.000008 | 0.282951 | 0.000016 | 6.34 | 11.6 | 423 | 533 | -0.98 |

| HS17-05-3 | 242.8 | 0.028464 | 0.000230 | 0.001110 | 0.000007 | 0.282954 | 0.000016 | 6.42 | 11.6 | 424 | 532 | -0.97 |

| HS17-05-4 | 242.8 | 0.016900 | 0.000988 | 0.000670 | 0.000038 | 0.283014 | 0.000018 | 8.57 | 13.8 | 334 | 389 | -0.98 |

| HS17-05-5 | 242.8 | 0.017065 | 0.000089 | 0.000703 | 0.000004 | 0.282999 | 0.000017 | 8.02 | 13.2 | 356 | 425 | -0.98 |

| HS17-05-6 | 242.8 | 0.010922 | 0.000090 | 0.000425 | 0.000003 | 0.282999 | 0.000015 | 8.03 | 13.3 | 353 | 421 | -0.99 |

| HS17-05-7 | 242.8 | 0.019116 | 0.000357 | 0.000741 | 0.000010 | 0.282943 | 0.000015 | 6.03 | 11.3 | 436 | 553 | -0.98 |

| HS17-05-8 | 242.8 | 0.021709 | 0.000173 | 0.000873 | 0.000008 | 0.282972 | 0.000016 | 7.09 | 12.3 | 395 | 487 | -0.97 |

| HS17-05-9 | 242.8 | 0.016488 | 0.000241 | 0.000661 | 0.000008 | 0.283001 | 0.000016 | 8.11 | 13.3 | 352 | 419 | -0.98 |

| Scheme 87. | Rb(μg/g) | Sr(μg/g) | 87Rb/86Sr | 87Sr/86Sr(2σ) | (87Sr/86Sr)ⅰ | Sm(μg/g) | Nd(μg/g) | 147Sm/144Nds | 143Nd/144Nds | 143Nd/144Nd(t) | εNd(0) | εNd(t) | TDM2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS17-09 | 60.98 | 509.54 | 0.3466 | 0.70508 | 0.703882 | 2.83 | 15.23 | 0.1122 | 0.512900 | 0.512721 | 5.10 | 7.72 | 387 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).