1. INTRODUCTION

Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty (UKA) and Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) represent crucial surgical options for managing knee osteoarthritis, each with distinct implications for patient outcomes. As surgical paradigms evolve and indications for UKA expand, its utilization is increasing [

1,

2], with studies suggesting that up to 20% of osteoarthritis patients could benefit from this targeted approach. [

3] UKA offers the advantage of preserving the healthy knee compartment, which can lead to shorter recovery times and superior functional outcomes, particularly regarding range of motion and pain reduction during recovery. [

4,

5] In contrast, while TKA entails a longer initial recovery, it often provides significant long-term relief and enhanced joint function. [

5,

6]

UKA Has several economic advantages. Shorter hospital stays, reduced blood loss, and consequently, fewer blood transfusions translate to decreased overall healthcare costs [

7,

8,

9,

10]. These benefits make UKA an increasingly attractive option for well-selected patients. However, the decision between UKA and TKA is highly individualized. Several patient factors must be meticulously considered, including the severity and location of the arthritis, age and activity level, and overall health status. Additionally, implant longevity and the potential need for revision surgery, which is typically lower with TKA, are crucial considerations [

11].

Recent studies highlight that patient undergoing UKA experience reduced postoperative pain, return to work more swiftly, and have an enhanced range of motion than those treated with TKA. [

12,

13,

14]. While some studies question the superiority of UKA over TKA, they consistently affirm that UKA achieves at least equivalent functional outcomes, thereby supporting its use as an effective alternative in appropriate clinical scenarios. [

15,

16]

Our study, utilizing data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) involving 68,445 UKA patients and 2,538,480 TKA patients, seeks to compare hospitalization characteristics, complications, and costs associated with these procedures. This comprehensive analysis aims to enhance our understanding of the practical implications, benefits, and limitations of UKA relative to TKA, providing valuable insights that could influence future advancements in patient-centered care and healthcare resource allocation.

2. METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

This retrospective analysis utilized data from the NIS, a large administrative database capturing inpatient stays in the United States. We included patients who underwent UKA or TKA identified using specific ICD-10 procedure codes (provided in Appendix). The study period spanned from January 1st, 2016, to December 31st, 2019 which is the latest available data within the NIS system at the time of the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients undergoing elective UKA or TKA during the study period were included. We excluded patients with non-elective admissions, prior knee surgery, or revision surgeries to maintain data homogeneity. This yielded a cohort of 2,606,925 patients: 68,445 undergoing UKA and 2,538,480 undergoing TKA.

Propensity Score Matching

To minimize confounding factors, propensity score matching was performed using MATLAB 2024. We matched patients undergoing UKA to those undergoing TKA based on several characteristics, including hospital size, patient location (urban/rural), median household income, hospital region, total discharges within the NIS dataset, comorbidities, payer type, sex, and race. This process resulted in a balanced dataset of 136,890 patients (68,445 UKA and 68,445 TKA).

Outcome Measures

Following propensity score matching, we compared the following outcomes between the UKA and TKA groups: in-hospital mortality, length of stay, postoperative complications, and overall hospitalization costs.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 26 and included chi-square tests, independent samples t-tests, and risk ratio calculations. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used.

Ethical Considerations

This study received exempt status from the institutional review board due to the de-identified nature of the NIS dataset.

3. RESULTS

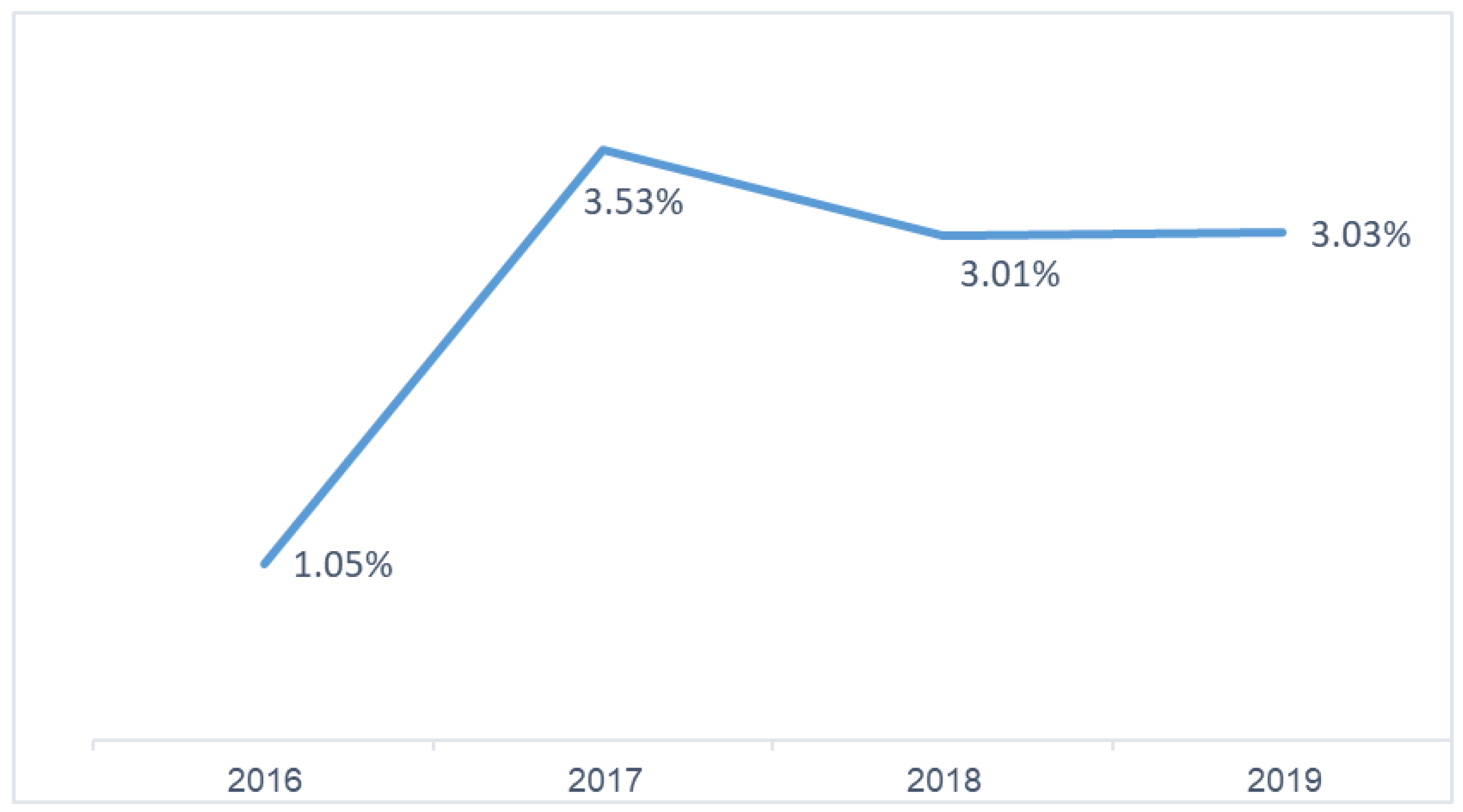

Our analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2016 to 2019 investigated the UKA relative to TKA procedures. Examining the proportion of UKA procedures among all knee arthroplasties, we observed a statistically significant increase (p < 0.0001) in the prevalence of UKA over the study period as shown in

Figure 1. This trend manifested as a sharp rise in the percentage of UKA procedures from 1.05% in 2016 to 3.53% in 2017, while the utilization of UKA from 2017 to 2019 plateaued.

Primary osteoarthritis is the leading cause for both UKA and TKA procedures, As shown in the

Table 1. It accounts for nearly all surgeries, with 97.35% for UKA and 97.70% for TKA. Post-traumatic arthritis is the second most common etiology, affecting a small percentage of patients undergoing both procedures (1.13% for UKA and 1.46% for TKA). Rheumatoid arthritis, osteonecrosis, leg deformity, malignant neoplasm, and other unspecified etiologies are less frequent causes for both UKA and TKA.

To understand potential differences between UKA TKA patients, we analyzed their demographic and clinical characteristics before applying propensity score matching. This analysis included all available data.

Our analysis revealed notable differences between the two groups. Patients undergoing UKA tended to be younger than those undergoing TKA. Additionally, the prevalence of comorbidities differed between the groups.

Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of various parameters for UKA and TKA patients before propensity score matching. It highlights key differences in age, sex, payer information, and the prevalence of specific comorbidities.

In order to overcome potential selection bias and baseline differences, a propensity score-matched analysis was performed. As discussed in the methods section, selection bias can arise when comparing outcomes between UKA TKA. To address this and ensure a fair comparison, we employed this statistical technique that balances baseline characteristics between the two groups.This approach ensures that any observed differences in outcomes can be more confidently attributed to the type of surgery itself, rather than pre-existing variations between the patient populations undergoing UKA and TKA.

After propensity score matching, the two groups were observed to be statistically equivalent across all parameters presented in

Table 3. This indicates that the propensity score matching method successfully balanced the baseline characteristics between patients undergoing UKA and TKA, ensuring that any observed differences in outcomes could be attributed to the type of surgery rather than underlying patient demographics or comorbidities.

In our analysis comparing hospitalization outcomes between UKA TKA in propensity score-matched cohorts, several key findings emerged. Firstly, the incidence of mortality during hospitalization was found to be low in both UKA and TKA groups, with rates of 0.015% for each. However, disparities were observed in the length of hospital stay and total charges incurred. Patients undergoing UKA had a significantly shorter mean length of stay compared to those undergoing TKA (1.53 days vs. 2.47 days, respectively; P<0.0001). Additionally, TKA was associated with higher mean total charges compared to UKA by 5537$.

In our investigation comparing postoperative complications between UKA TKA in propensity score-matched cohorts, several important findings emerged. As showen in

Table 5 our analysis revealed that UKA did not demonstrate superiority over TKA in terms of some postoperative complications. UKA exhibited higher rates of intraoperative fracture and pulmonary edema compared to TKA, with statistically significant differences observed in both instances (P=0.007 and P<0.0001, respectively). While the incidence of venous thromboembolism was slightly lower in UKA compared to TKA, this difference was not statistically significant (P=0.06). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the incidence of heart failure between the two procedures (P=0.44).

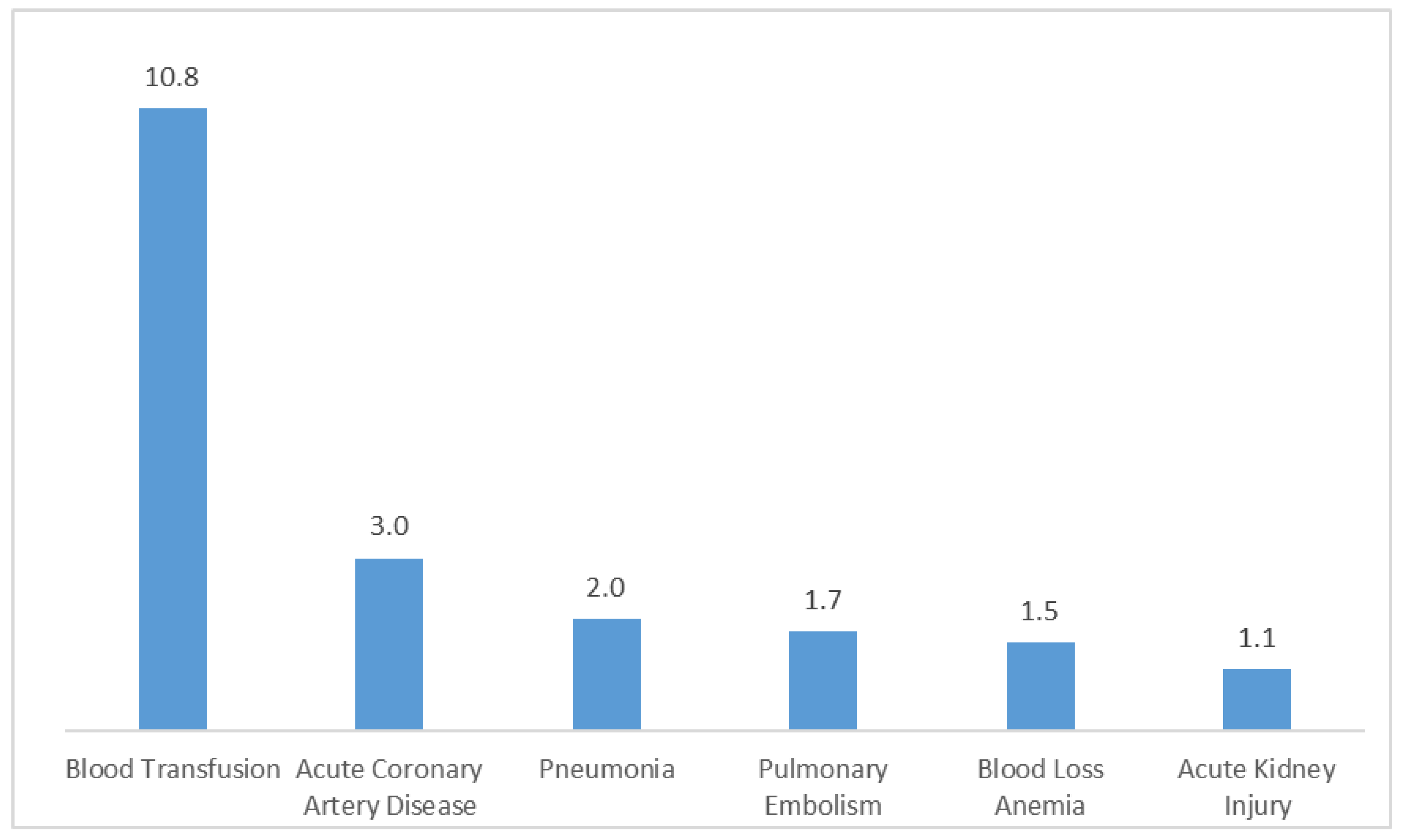

In

Figure 2, the risk estimates illustrate the increased likelihood of experiencing various postoperative complications when opting for TKA over UKA. Risk signifies the elevated probability or chance of encountering a specific complication following TKA compared to UKA. The risk estimates quantify this increased likelihood, delineating the relative rise in risk associated with TKA for each complication:

Blood Transfusion: The risk of requiring a blood transfusion following TKA is substantially elevated by a factor of 10.812 compared to UKA (95% CI: 8.353 - 13.996, P<0.0001). Blood Loss Anemia: TKA is associated with a 54.7% increase in the risk of developing blood loss anemia relative to UKA (Risk Estimate: 1.547, 95% CI: 1.509 - 1.585, P<0.0001). Acute Coronary Artery Disease: The likelihood of experiencing acute coronary artery disease postoperatively is notably higher with TKA, presenting a 200.5% increase in risk compared to UKA (Risk Estimate: 3.005, 95% CI: 2.385 - 3.787, P<0.0001).

Pulmonary Embolism: Opting for TKA over UKA entails a 72.3% rise in the risk of pulmonary embolism (Risk Estimate: 1.723, 95% CI: 1.347 - 2.204, P<0.0001). Pneumonia: TKA is associated with a 95.1% higher risk of developing pneumonia postoperatively compared to UKA (Risk Estimate: 1.951, 95% CI: 1.536 - 2.478, P<0.0001). Acute Kidney Injury: TKA presents a 7.2% higher risk compared to UKA (Risk Estimate: 1.072, 95% CI: 1.011 - 1.137, P=0.017). These risk estimates elucidate the comparative increase in the likelihood of experiencing these complications following TKA relative to UKA.

4. DISCUSSION

Our investigation, utilizing the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2016 to 2019, highlighted a significant increase in the utilization of UKA compared to TKA, particularly noting a surge from 1.05% in 2016 to 3.53% in 2017. This significant increase in UKA procedures aligns with recent trends reported in the literature. [

1,

2] While TKA remains the predominant surgery for severe knee conditions, particularly in older adults, UKA has gained favor due to its less invasive nature and faster recovery times. Yet many surgeons still tend to choose TKA over UKA due to its proven efficacy, lower revision rates, and higher patient satisfaction. [

17] Not surprising that the primary etiology for both surgical interventions was predominantly primary osteoarthritis, accounting for over 97% of cases, with other causes like post-traumatic and rheumatoid arthritis being far less common.

Costs

Our comprehensive analysis of hospitalization outcomes in matched cohorts undergoing UKA and TKA revealed a significantly shorter LOS in the UKA group. This finding aligns with previous studies demonstrating similar reductions in LOS. [

18,

19] Moreover, some studies have even explored the comparison of lateral compartment arthroplasty to TKA. [

7] From a financial perspective, the shorter LOS associated with UKA translates to substantial cost savings for the hospital. Our analysis suggests a potential annual saving of 1,817.4 inpatient ward bed days, corresponding to an estimated cost reduction of

$2,124,540.60 and up to

$2,397.28 per patient. [

20] Furthermore, our data demonstrates a statistically significant difference in total charges, with the TKA group incurring an additional

$5,537 compared to the UKA group. Supporting this finding, a prior study reported not only lower direct hospital costs for UKA but also shorter anesthesia and operative times, further contributing to reduced overall costs. [

9]

Complications

In our study, UKA was associated with slightly higher rates of intraoperative fractures and pulmonary edema compared to TKA. These complications, although relatively infrequent, can have significant clinical implications. Intraoperative fractures may necessitate additional surgical intervention, potentially delaying recovery and increasing healthcare costs [

18]. Pulmonary edema, although rare, requires prompt management to prevent serious outcomes such as respiratory failure.

TKA was linked to higher rates of several serious complications, including blood transfusion, blood loss anemia, acute coronary artery disease, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, and acute kidney injury. These findings highlight the necessity for careful patient selection and surgical planning to mitigate risks and optimize outcomes for both procedures.

Pros of UKA

UKA offers several significant advantages over TKA. One of the primary benefits is the preservation of healthy knee compartments, which contributes to a quicker recovery and less postoperative pain [8,911]. Patients undergoing UKA typically experience a shorter hospital stay and lower overall healthcare costs due to reduced blood loss and fewer complications as shown in our study and in previous studies [

8,

18,

19]. Additionally, UKA patients often achieve better postoperative range of motion and a higher level of activity at the time of discharge compared to those undergoing TKA. This improved functional outcome is particularly beneficial for younger, more active patients. Furthermore, UKA is associated with a lower incidence of some serious complications, such as blood transfusion and acute coronary artery disease, making it an attractive option for well-selected patients.

Cons of UKA

UKA offers several advantages, but its broader adoption is tempered by concerns regarding potentially higher revision rates. Data from the German Arthroplasty Registry (EPRD) suggests an increased risk of early failure (after 12 months) in UKA compared to TKA, with this risk doubling by the four-year mark [

21]. Notably, some of this disparity has been attributed to the procedure being performed at low-volume hospitals [

22,

23]. Additionally, higher body mass index (BMI) has been correlated with a propensity for revision surgery in UKA patients. [

24]

Limitations and Strengths

This study leverages a large, nationally representative dataset to compare real-world outcomes of UKA and TKA. Propensity score matching mitigates confounding factors, strengthening the comparison. However, the use of administrative data from the NIS limits the analysis to in-hospital outcomes and lacks long-term patient perspectives. Additionally, the retrospective nature and potential coding errors might influence the results. Future research should incorporate long-term follow-up and patient-reported measures for a more holistic picture.

Despite these limitations, the study's large sample size and comprehensive analysis offer valuable insights into patient demographics, clinical characteristics, hospitalization details, and cost implications of UKA vs. TKA. The findings highlight shorter hospital stays and lower costs for UKA, alongside differing complication profiles. This valuable contribution fuels the discussion around optimal surgical approaches for knee osteoarthritis, paving the way for future research that ultimately improves patient care and resource allocation in knee arthroplasty.

5. Conclusions

This study shows the importance of understanding the trade-offs between UKA and TKA for optimal surgical decision-making. By highlighting UKA's advantages in terms of shorter hospital stays and reduced costs, alongside its specific complication profile, the study empowers both healthcare providers and patients when navigating knee arthroplasty options.

Moving forward, research should prioritize long-term outcomes and patient-reported measures to gain a more comprehensive picture of UKA and TKA's impact on quality of life. Ongoing advancements in surgical techniques and post-operative care protocols will ultimately lead to improved outcomes and increased satisfaction for patients undergoing knee arthroplasty.

List of Abbreviations (A-Z):

HCUP: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

ICD-10: International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision

LOS: Length of Stay

NIS: Nationwide Inpatient Sample

SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

TKA: Total Hip Arthroplasty

UKA: Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted under exempt status granted by the institutional review board, and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the de-identified nature of the NIS dataset.

Acknowledgements

Irrelevant.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Jennings JM, Kleeman-Forsthuber LT, Bolognesi MP. Medial unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(5):166–76. [CrossRef]

- Halawi MJ, Barsoum WK. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty: Key concepts. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2017;8(1):11–3. [CrossRef]

- Satku K. Unicompartmental knee Arthroplasty: Is it a step in the right direction? - surgical options for osteoarthritis of the knee. Singap Med J. 2003;44(11):554–6.

- Tille, E., Beyer, F., Auerbach, K. et al. Better short-term function after unicompartmental compared to total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22, 326 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Soh, T.L.T.; Loh, N.L.K.; Ho, S.W.L.; Kaliya-Perumal, A.-K.; Kau, C.Y. Short-Term Functional Outcomes of Unicompartmental versus Total Knee Arthroplasty in an Asian Population. Rheumato 2023, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit M. The Renaissance of Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty appears rational - A radiograph-based comparative Study on adverse Events and patient-reported Outcomes in 353 TKAs and 98 UKAs. PLoS ONE. 2021 Sep 16;16(9):e0257233. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu Y, Ma T, Wen T, Yang T, Xue L, Xue H. Does Unicompartmental knee replacement offer improved clinical advantages over Total knee replacement in the treatment of isolated lateral osteoarthritis? A Matched Cohort Analysis From an Independent Center. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(8):2016–21. [CrossRef]

- Siman H, Kamath AF, Carrillo N, Harmsen WS, Pagnano MW, Sierra RJ. Unicompartmental knee Arthroplasty vs Total knee Arthroplasty for medial compartment arthritis in patients older than 75 years: Comparable reoperation, revision, and complication rates. J Arthroplast. 2017;32(6):1792–7. [CrossRef]

- Shankar S, Tetreault MW, Jegier BJ, Andersson GB, Della Valle CJ. A cost comparison of unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2016;23(6):1016–9. [CrossRef]

- Schwab PE, Lavand’homme P, Yombi JC, Thienpont E. Lower blood loss after unicompartmental than total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:3494–500.

- Patient relevant outcomes of unicompartmental versus total knee replacement: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019 Apr 2;365:l1032.Erratum for: BMJ. 2019 Feb 21;364:l352. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blevins JL, Carroll KM, Burger JA, Pearle AD, Bostrom MP, Haas SB; et al. Postoperative outcomes of total knee arthroplasty compared to unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A matched comparison. Knee. 2020;27(2):565–71. [CrossRef]

- Lum ZC, Lombardi AV, Hurst JM, Morris MJ, Adams JB, Berend KR. Early outcomes of twin-peg mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty compared with primary total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(10_Supple_B):28–33. [CrossRef]

- Hauer G, Sadoghi P, Bernhardt GA, Wolf M, Ruckenstuhl P, Fink A; et al. Greater activity, better range of motion and higher quality of life following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A comparative case–control study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140(2):231–7. [CrossRef]

- Liebensteiner M, Köglberger P, Ruzicka A, Giesinger JM, Oberaigner W, Krismer M. Unicondylar vs total knee arthroplasty in medial osteoarthritis: A retrospective analysis of registry data and functional outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140(4):545–9.

- Goh GS-H; et al. Unicompartmental knee Arthroplasty achieves greater flexion with no difference in functional outcome, quality of life, and satisfaction vs Total knee Arthroplasty in patients younger than 55 years. A Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:355–61.

- Murray DW, Parkinson RW. Usage of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt. J. 2018;100:455–60.

- Kulshrestha V, Datta B, Kumar S, Mittal G. Outcome of Unicondylar Knee Arthroplasty vs Total Knee Arthroplasty for Early Medial Compartment Arthritis: A Randomized Study. J Arthroplasty. 2017 May;32(5):1460-1469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh J, Liow MHL, Pua YH, Chew ES, Chia SL, Lo NN, Yeo SJ, Chen JY. Early postoperative straight leg raise is associated with shorter length of stay after unilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2021 Jan-Apr;29(1):23094990211002294. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee WC, Neoh EC, Wong LP, Tan KG. Shorter length of stay and significant cost savings with ambulatory surgery primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty in Asians using enhanced recovery protocols. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2024 Feb 25;50:102379. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimberg A, Jansson V, Lützner J, Melsheimer O, Morlock M, Steinbrück A. Annual Report German Arthroplasty Registry 2019. EPRD Deutsche Endoprothesenregister gGmbH. ISBN: 978-3-9817673-4-6.

- Liddle AD, Pandit H, Judge A, Murray DW. Effect of surgical caseload on revision rate following total and unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Jt Surg - Am Vol. 2016;98(1):1–8.

- Jeschke E, Gehrke T, Günster C, Heller KD, Malzahn J, Marx A; et al. Impact of case numbers on the 5-year survival rate of Unicondylar knee replacements in Germany. Z Orthop Unfall. 2018;156(1):62–7.

- Lee HJ, Xu S, Liow MHL, Pang HN, Tay DK, Yeo SJ, Lo NN, Chen JY. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in obese patients, poorer survivorship at 15 years. J Orthop. 2024 Apr 2;53:156-162. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).