1. Introduction

Spastic cerebral palsy (SCP) is the most common form of cerebral palsy (CP), marked by motor dysfunctions resulting from early brain damage. SCP significantly affects the quality of life of those affected and presents significant challenges to healthcare systems worldwide. In Mexico, SCP is a notable public health issue, with scarce epidemiological data available. However, recent research indicates an increasing prevalence that mirrors global patterns. Identifying the epidemiology, causes, and management of SCP is crucial to improve outcomes and guide healthcare policy and interventions. This article seeks to offer a detailed overview of the current state of SCP, with a focus on recent data from Mexico and around the world [

1,

2].

Recent epidemiological investigations underscore the escalating prevalence of SCP both within Mexico and globally. In Mexico, precise prevalence rates remain indeterminate due to under-reporting and variability in diagnostic criteria; however, emerging evidence indicates an increasing burden of SCP. On a global scale, SCP affects approximately 2 out of every 1000 live births, with elevated rates observed in low- and middle-income countries. These disparities underscore the intricate interplay between socioeconomic factors, access to healthcare, and early intervention services in shaping the epidemiological landscape of SCP [

3,

4]. Moreover, the etiology of SCP encompasses a multifactorial interplay of genetic, prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors. Contemporary research highlights the role of prenatal insults, such as intrauterine infections, maternal health conditions, and genetic predispositions, in predisposing individuals to SCP. Perinatal factors such as birth asphyxia, prematurity, and low birth weight further augment the risk profile. Postnatally, environmental factors, including inadequate access to health services and socioeconomic disparities, exacerbate the risk of developing SCP. Comprehending these risk factors is imperative for the implementation of targeted prevention strategies and interventions [

5].

In addition, cerebral palsy is the leading cause of childhood disabilities, with a frequency of 2-2.5 per 1,000 births in western countries [

6]. In France, for example, there are approximately 130,000 affected individuals [

1]. It is estimated that two out of every 1,000 newborns will develop cerebral palsy, with approximately 40% of the cases being severe [

7]. Around 10,000 babies and children are diagnosed with the disease each year [

2].

The incidence of cerebral palsy is 2.5 per 1,000 live births in developing countries and 2.0 per 1,000 live births in developed countries. Despite progress in preventing and treating certain causes of cerebral palsy, risk factors such as prematurity, low birth weight, maternal-child malnutrition, and inadequate prenatal care contribute to its prevalence. Some authors, such as Odding et al. in [

5], suggest that the prevalence of cerebral palsy may have increased over the last 30 years due to these risk factors.

The clinical manifestations of SCP encompass a broad spectrum of motor impairments, including hypertonia, spasticity, impaired motor coordination, and delayed developmental milestones. The diagnosis is based on comprehensive clinical evaluations, neuroimaging studies, and standardized neurological evaluations. Recent advances in neuroimaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), have facilitated early diagnosis and prognostication, thus allowing personalized interventions and family counseling. In contrast, optimal management strategies for SCP require a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates early intervention, rehabilitation therapies, pharmacotherapy, orthopedic interventions, and assistive devices. Contemporary research highlights the efficacy of early intervention programs, including physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy, in improving motor impairments and improving functional outcomes. Emerging interventions, such as dolphin-assisted therapy (DAT), have garnered attention for their potential benefits in increasing motor function, psychological well-being, and quality of life in children with SCP. However, more research is imperative to elucidate the long-term efficacy and underlying mechanisms of DAT in SCP management; see

Figure 1.

Rosenbaum et al. in [

6] elucidate that cerebral palsy encompasses various types, classified both anatomically and physiopathologically, contingent upon the affected body regions and the severity of symptomatic manifestations. Monoplegia is characterized by the involvement of a single limb, typically the lower limb. Hemiplegia affects both limbs on the same side, with a greater impact on the upper limb compared to the lower limb. Paraplegia involves both lower limbs symmetrically. Diplegia predominantly affects the lower limbs more than the upper limbs and is accompanied by fine motor and sensory abnormalities in the upper limbs. Quadriplegia involves all four limbs equally, while maintaining normal head and neck control. Cerebral palsy is associated with numerous complications, including gait disturbances, which are marked by impaired balance, alignment, postural control, and locomotion.

Another complication refers to hip development, where there exists a risk of stiffness and the emergence of contractures and deformities. Children must experience a variety of positions throughout the day, particularly those with movement limitations, postural contractures, and deformities. Most children with cerebral palsy exhibit an altered gait pattern. Due to spasticity, muscle weakness, and postural instability, approximately 90% of these children experience difficulties in ambulation, leading to reduced speed and endurance. This condition is characterized by knee flexion, which progressively deteriorates, thus reducing speed, step length, single-leg support time, and range of motion in the pelvis, knee, and ankle. Given the critical role of walking in the functional capacity of a child, the use of technical aids is essential. These aids, which facilitate sitting, mobility, standing, and, in particular, walking, can partially or entirely mitigate disability-related challenges, thus improving the level of functional independence and significantly improving quality of life.

In addition to conventional therapeutic interventions employing technical aids such as walking aids, crutches, and wheelchairs, alternative therapies such as dolphin-assisted therapy (DAT) present distinctive opportunities for children with physical disabilities. Although assistive devices are indispensable for improving mobility and functionality, DAT offers a supplementary modality by leveraging the therapeutic advantages of dolphin interaction. During DAT sessions, children are exposed to sensory stimulation, physical activity, and emotional support in a new and stimulating environment. In addition, the beneficial impacts of DAT on muscle tone, mobility, and overall well-being have been substantiated in clinical studies [

8]. Consequently, incorporating DAT into the treatment regimen along with the prescription of assistive devices can provide a comprehensive approach to addressing the multifaceted needs of pediatric patients with physical disabilities.

This work is structured into five main sections. The second section reviews related work, providing a comprehensive overview of existing methodologies and highlighting the gap that our approach aims to fill. The third section details the methodology, describing how we train a Siamese network using data from CP patients undergoing DAT sessions to learn patterns and similarities between pre- and post-therapy evaluations. This network architecture allows accurate comparisons within the same feature space, identifying biomarkers indicative of therapy effectiveness. The fourth section presents the results, showcasing promising findings that reveal distinct patterns in the network’s output that are correlating with improvements in CP symptoms post-DAT. Finally, the fifth section discusses the conclusions, emphasizing the potential utility of the Siamese Network as a quantitative biomarker to monitor therapy outcomes in children with CP, offering a more objective and quantifiable approach to assessing therapeutic interventions.

2. Related Work

Siamese Neural Networks (SNN) are a class of neural networks designed to identify similarities between two input items. Unlike traditional neural networks that focus on classification tasks, SNNs are tailored for comparison tasks. They consist of two identical subnets that process two different inputs simultaneously, and their outputs are then compared using a similarity metric. This architecture is particularly effective for tasks where determining the similarity or difference between inputs is crucial, such as matching patient data or diagnosis of disease. There are several key applications of SNNs in healthcare care, emphasizing their versatility and effectiveness, that is, SNNs can be used to match patient records based on similarity, helping in patient diagnosis and treatment planning. By comparing new patient data with existing records, SNNs help identify similar cases and suggest potential diagnoses and treatment options. Advantages of ussing SNN’s in health care lies that this kind of neural neuwork improves diagnostic accuracy by leveraging historical data, providing a data-driven basis for medical decisions. In this way, in disease diagnosis, SNNs can compare medical images, such as radiographs or MRI scans, to diagnose diseases. By learning the patterns and features associated with specific conditions, SNNs can accurately identify similar cases in new patient images.This leads to faster and more accurate diagnoses, reducing the reliance on subjective interpretation by medical professionals.

Siamese neural networks have shown significant promise in various healthcare applications, demonstrating their versatility and effectiveness in improving diagnostic accuracy, thus, Li and Deng in [

9] discuss the application of Siamese neural networks for healthcare, focusing on patient similarity matching, which improves diagnostic precision and patient management by learning from large datasets. This study not only highlights the scalability and high accuracy of Siamese networks, but also notes the requirement for substantial training data and the complexity of implementation. In addition, the work by Li and Deng delves into the implementation and benefits of Siamese Neural Networks (SNNs) within the healthcare domain. The authors explore how SNN can significantly improve various healthcare processes by providing robust and efficient methods to compare and analyze complex medical data.

For mediacal appplicatins, SNNs can compare DNA sequences to identify genetic similarities and mutations, for instance. In this poarticular case, this application is crucial to understanding genetic disorders and developing personalized medicine approaches. SNNs provide a scalable solution for processing large volumes of genomic data, allowing the identification of rare genetic conditions. Futhermore, SNN’s can be used for detailing explanation of the technical implementation of SNNs, including network architecture, training methodologies, and performance metrics. The twin subnetworks in SNNs are typically convolutional neural networks (CNNs) when dealing with image data, or recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for sequential data like time-series or text. Training SNNs involves creating pairs of similar and dissimilar inputs. The network learns to minimize the distance between similar pairs while maximizing the distance between dissimilar pairs. The evaluation of SNNs is based on metrics such as precision, precision, recall, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC), ensuring robust performance on different healthcare tasks. SNNs excel in tasks requiring precise comparison and matching, leading to improved diagnostic accuracy. These kinds of neural network can handle large datasets efficiently, making them suitable for big data applications in healthcare. In addition, SNNs can be applied to various data types, including images, text, and genomic sequences, demonstrating their broad applicability. The performance of SNNs is highly dependent on the quality and quantity of training data. Poor-quality data can lead to inaccurate comparisons. Training and deploying SNNs require significant computational power, which can be a barrier for some healthcare institutions. The implementation and fine-tuning of SNNs are complex, necessitating expertise in neural networks and domain-specific knowledge.

In relation to this Dolphin-Assisted Therapy Project, the insights from this study are particularly relevant to this work. Using SNNs’ ability to compare pre and post-therapy data, the project can objectively measure the effectiveness of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy. The network can identify patterns and biomarkers indicative of therapy success, providing a quantitative basis for evaluating therapeutic outcomes. The approach aligns with the advantages of SNNs highlighted by Li and Deng , including high accuracy and scalability, while also addressing the challenge of ensuring high-quality input data for reliable evaluations. State-of-the-art SNN architectures underscore the transformative potential of Siamese Neural Networks in healthcare, offering robust solutions for patient matching, disease diagnosis, and genomic analysis. Despite challenges such as data quality and computational requirements, the benefits of enhanced accuracy and scalability make SNNs a valuable tool in modern healthcare. The methodology and insights of this article provide a solid foundation for the application of SNNs in innovative projects, such as the evaluation of the impact of dolphin-based therapy on pediatric cerebral palsy, ultimately contributing to more objective and effective therapeutic evaluations.

In a different context, Li and Deng explore the use of Siamese neural networks for the recognition of continuous speech emotions in ambulatory settings. This application is particularly relevant for mobile health, allowing real-time monitoring of patients’ emotional states. Although this approach offers real-time processing capabilities, it is sensitive to noise and requires clean input data to function effectively. Gopalan and Raja in [

10] use Siamese neural networks to extract drug–drug interactions from biomedical text. This method automates the extraction process, significantly improving drug safety by identifying potential adverse interactions. The main advantage of this approach is its ability to handle large volumes of textual data, although its effectiveness is contingent upon the quality of the input text. Panigrahi and Desai in [

11] applied Siamese neural networks for the detection of anomalies in healthcare data, grouped anomalies that could indicate potential health problems. This method enhances data security and anomaly detection, but is computationally intensive and can produce false positives. Koch et al. in [

12] focus on one-shot image recognition using Siamese neural networks. This application is beneficial for diagnosing rare diseases in which only a single example may be available. The key advantage is the minimal training data required, though the network’s performance can be limited by the quality of the single samples available. Wang and Yan in [

13] employ Siamese convolutional neural networks for image analysis in healthcare, improving diagnostic accuracy through detailed image comparison. This method excels in extracting detailed features from images, but comes with high computational costs and extensive preprocessing requirements. Parodi and Kooij in [

14] investigate the use of Siamese networks for non-intrusive load monitoring, which, while more relevant to facility management, shows the versatility of Siamese networks in handling various data types. Its primary advantage lies in its non-intrusive nature, although it is less directly applicable to patient care. Wang and Feng in [

15] explore the use of Siamese networks for biomedical image registration, facilitating the alignment of images from different modalities. This application is crucial for multimodal analysis, enhancing image alignment, but requiring high-quality input images to function effectively. Fonseca and Cruz in [

16] demonstrate the application of Siamese networks for biosignal classification, specifically for sleep stage scoring. This method offers high accuracy in classifying biosignals, which is essential for sleep studies, although it relies on high-quality biosignal data and complex signal processing. Yoon and Park in [

17] use Siamese networks to provide medical diagnoses with uncertainty estimation, which is crucial to understanding confidence levels in diagnostic predictions. This approach improves diagnostic confidence but is computationally intensive and relies on comprehensive training data.

The similarities among these studies lie in their use of Siamese networks to compare data inputs for various healthcare applications, all aiming to improve diagnostic accuracy and provide more objective assessments. Differences include the types of data used (text, images, biosignals) and specific network architectures (convolutional, clustering-based). Advantages often include high accuracy and robustness, while disadvantages often involve high computational requirements and dependence on high-quality input data.

Relating these findings to this work, the comparative capabilities of Siamese networks are particularly relevant. By comparing pre- and posttherapy data, these networks can identify biomarkers indicative of therapy effectiveness. The project’s focus on objective assessment aligns with the uncertainty estimation techniques discussed, enhancing the reliability of evaluations. Methodologies from studies on emotion recognition and anomaly detection can ensure robust assessments, making Siamese networks a promising tool for evaluating Dolphin-Assisted Therapy’s impact on children with cerebral palsy.

3. Methodology

3.1. Mathematical Basis

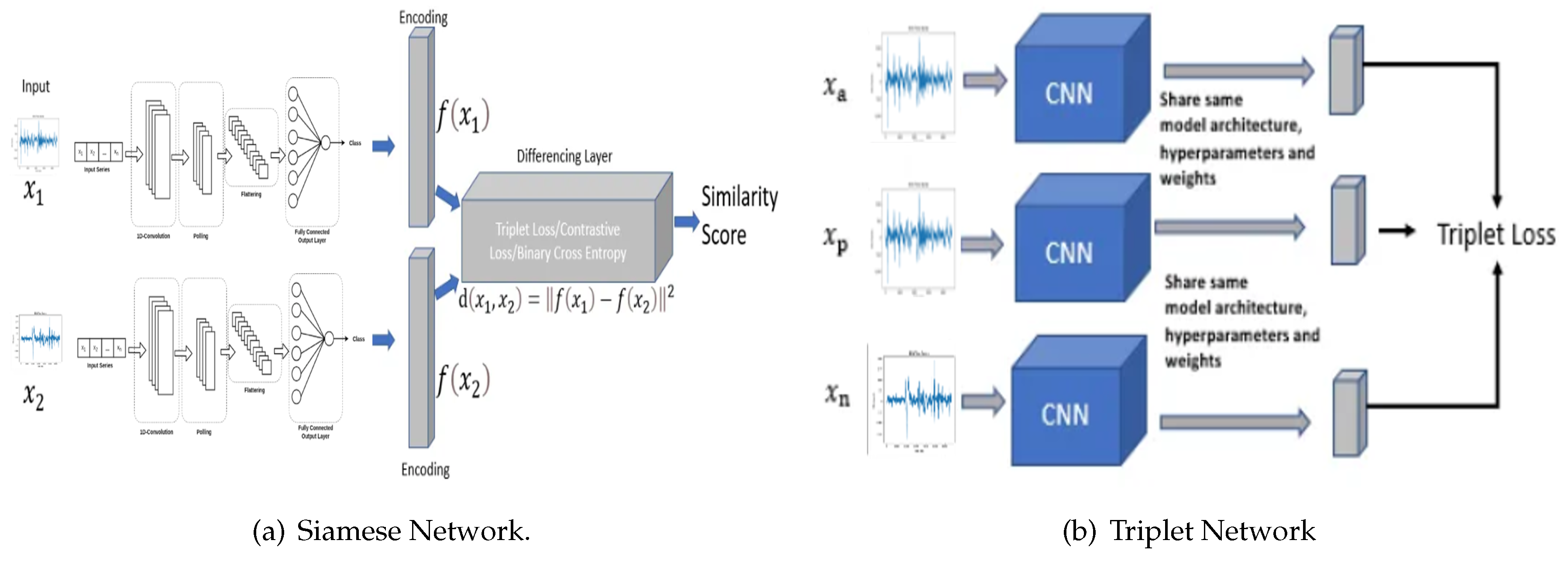

Conventional methodologies encompass three critical processes: feature extraction, distance computation, and the retrieval of analogous features corresponding to a given query image or time series. These traditional systems face three principal challenges: i) the semantic gap, ii) the computation of similarity and dissimilarity, and iii) the memory overhead required for storing visual descriptors. In this study, we advocate for the utilization of Siamese and triplet CNN architectures for the retrieval of both analogous and non-analogous EEG. The Siamese architecture employs two identical deep learning convolutional neural networks with shared synaptic weights, using the contrastive cost function. The triplet architecture, akin to the Siamese architecture, employs three deep learning convolutional neural networks with shared synaptic weights, but utilizes the triplet cost function.

In contrast to the manual process of content description employing low-level features such as frequency, these Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) provide a superior description by leveraging the intrinsic information of the quantitative electroencephalogram (EEG). This proposed methodology thereby mitigates the semantic gap. Distance calculation, embedded within the cost function of these neural architectures, facilitates learning of similarities and dissimilarities between various classes of EEGs in the database, thus enhancing discriminative power. Furthermore, it is unnecessary to store characteristic vectors, as the activation calculation of the neurons (forward propagation) can determine which time series most closely resemble the given EEG.

Figure 2a,b depict the Siamese and triplet CNN architectures, respectively. Furthermore,

Figure 2a illustrates that each network receives a pair of images as input, with the label variable indicating if the image pair is positive or negative. The depicted Siamese neural network architecture comprises a pair of images as input to a system constituted by two identical subnets with shared synaptic weights. The output of these subnetworks is subsequently processed by a cost function. This cost function is designed to minimize a distance metric (

,

, or cosine) between the feature representations of a positive pair of e.g. (

) and (

), while maximizing this metric for a negative pair of e.g.. In contrast to conventional CNNs, Siamese networks employ a contrastive cost function, which is defined by equ:ContrastiveCostFunction as follows:

In this context, let D represent the distance computed between the outputs of two convolutional neural networks, and , which is defined as . The variable Y functions as a binary label, indicating whether the image pairs belong to the same class () or to different classes (). Furthermore, m denotes a margin that specifies the required degree of similarity for time series within the same class, with . The presence of a margin implies that dissimilar pairs exceeding this threshold do not contribute to the loss.

The L2 distance between the outputs of the triplet Siamese network can be expressed as follows:

where

and

signify the representations of the features of the electroencephalograms (EEGs)

A and

B obtained from the Siamese network, with

n denoting the dimensionality of the feature space.

From

Figure 2b, within the framework of a Siamese triplet network, the inputs consist of three distinct time series: i) an anchor EEG denoted as

, ii) a positive EEG denoted as

, and iii) a negative EEG denoted as

. The network subsequently computes the embedded representations of these time series, designated as

,

, and

. Using the L2 distance, the network produces two values: i) the Euclidean distance between the anchor and the positive EEG, denoted as

; and ii) the Euclidean distance between the anchor and the negative EEG, denoted as

. Consequently, within the framework of the proposed triplet Siamese network, which utilizes inputs

,

, and

along with their corresponding embedded representations

, the two distance metrics of the Euclidean norm (L2) between the respective feature vectors are formally defined as follows:

where

,

, and

are the feature representations of the images

(anchor),

(positive), and

(negative) from the Siamese network, and

n is the number of dimensions in the feature space, i.e.

x and

are images belonging to the same class, while

belongs to a different class. In other words, triplet networks encode the distances of the images

and

with respect to the reference image

x. It should be noted that the objective of triplet networks (similar to Siamese networks) is to obtain a very large distance

between images

x and

, and a very short distance

between the images

x and

. The structure of this type of network can be seen in

Figure 2b. For training, we used a triplet loss function, which is defined by :

where

represents the anchor image,

denotes the positive image (belonging to the same class as the anchor),

signifies the negative image (belonging to a different class from the anchor), and

constitutes the margin imposed between positive and negative pairs. The operator

signifies the hinge function, which yields the maximum of

z and 0. Here, the function is described using the

notation to denote the L2 norm (Euclidean distance), which is crucial to ensure the desired distances between the anchor time series, positive and negative. Stated differently, these diverse architectures possess the capability to discern the inter-class and intra-class distances among images, addressing a prominent challenge currently recognized in the scholarly literature.

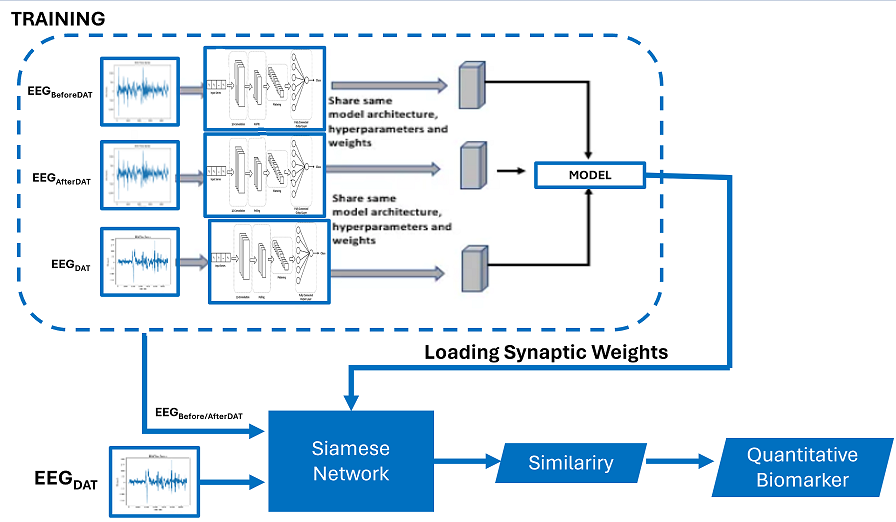

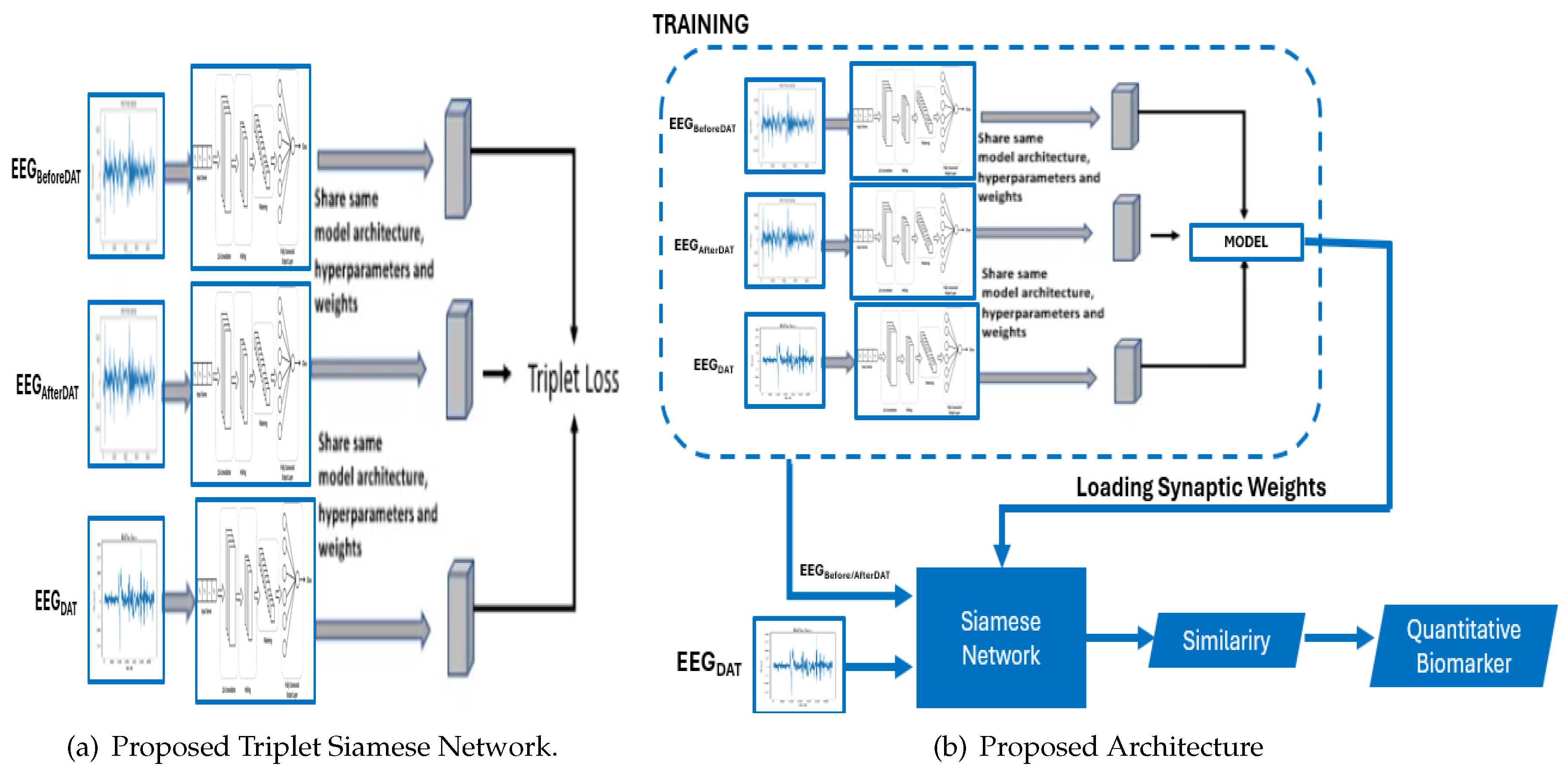

3.2. Proposed Architecture

The architecture of the Proposed Triplet Siamese Network for Time Series is delineated in fig:ProposedTripletSiamese. It is pertinent to underscore that triplet Siamese networks are an extension of Siamese networks, specifically engineered to discern and differentiate representations between pairs of electroencephalograms. In the context of time series analysis, the objective is to identify analogous or anomalous patterns within temporal sequences. Each time series is encapsulated as a sequence of characteristic vectors. The architecture employs two congruent branches of the Siamese network, with each branch processing an individual input time series. The shared layers are responsible for extracting salient features from the time series. The loss function is meticulously crafted to minimize the distance between the representations of analogous time series while maximizing the distance between the representations of dissimilar time series. The loss function is comprised of three components:

Anchor term: Representation of the anchor time series.

Positive term: Representation of a similar time series.

Negative term: Representation of a dissimilar time series.

If two time series are similar, we want their representations to be close in the latent space. If two time series are dissimilar, we want their representations to be separated in the latent space. The principal hypothesis posits that the electroencephalographic patterns observed pre- and post-intervention exhibit analogous characteristics. However, should a high degree of similarity be detected during the DAT, it would imply that the DAT did not exert a substantial impact on children with CP.

Figure 3.

Proposed architectures of the Siamese and Triplet Convolutional Neural Networks for assessing a Quantitative Biomarker.

Figure 3.

Proposed architectures of the Siamese and Triplet Convolutional Neural Networks for assessing a Quantitative Biomarker.

The proposed architecture harnesses the capabilities of these diverse architectures to mitigate the semantic gap and improve the discriminative efficacy of EEG. The proposed framework is depicted in Figure 6, which employs a triplet Siamese network and consists of two stages. The initial stage (dotted line block) represents the training phase, in which a Triplet Siamese CNN is used, illustrated in

Figure 2a. The EEG descriptors within the database are not retained; rather, only the synaptic weights of the trained network are preserved. The second stage is the process of retrieving similar EEG’s, in which one input of the Siamese network is the given query image, while the other input consists of all the time series in the database before or after the Dolphin Assisted Therapy, introduced one by one. The level of similarity between each pair of EEG is calculated in Equation (6) by applying the Euclidean distance to the two outputs of the Siamese Network:

Where and are the vectors of characteristics in the database of electroencephalograms before and after dolphin-assisted therapy and EEG during DAT, respectively, and is the L2 norm. Once the similarity value between each pair is obtained, the most similar ones to the given query are extracted. In this way, this system scheme is simplified as there is no need to store the descriptors. Additionally, the feature extractor and the similarity measure are embedded in a single process, a Siamese neural network.

3.3. Quantitative Biomarker

Then, we used a triplet network, whose training is performed as detailed in

Figure 2b. In this scheme, a binary label is not necessary; instead, we introduce three images into the network, two of the same class, and one image of a different class. The training is responsible for learning that images with the same semantic content should have very close distances, and images with different semantic content should have a very large distance. For the query stage, we only use two networks (instead of three) since ultimately all three networks share the same synaptic weights. As a result, we will have a Siamese network that will obtain the similarity level between the query image and each of the images in the database. As in the Siamese architecture, the image feature vectors are not stored and the similarity calculation, given by Equation (6) , is performed within the same neural architecture, as seen in

Figure 3b. Once the similarity between each pair of time series is obtained, the most similar EEG’s to the given query EEG are retrieved, when this time series is obtained during the DAT.

Finally, for the new quantitative biomarker proposed called

whose units are decibels (dB), we propose Equation (7), where it is observed that the more similar there is between brain activity at rest (

) compared to brain activity during dolphin-assisted therapy (

),

tends to zero. However, the more dissimilar it is, the more effective the therapy was for the patient, then

.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

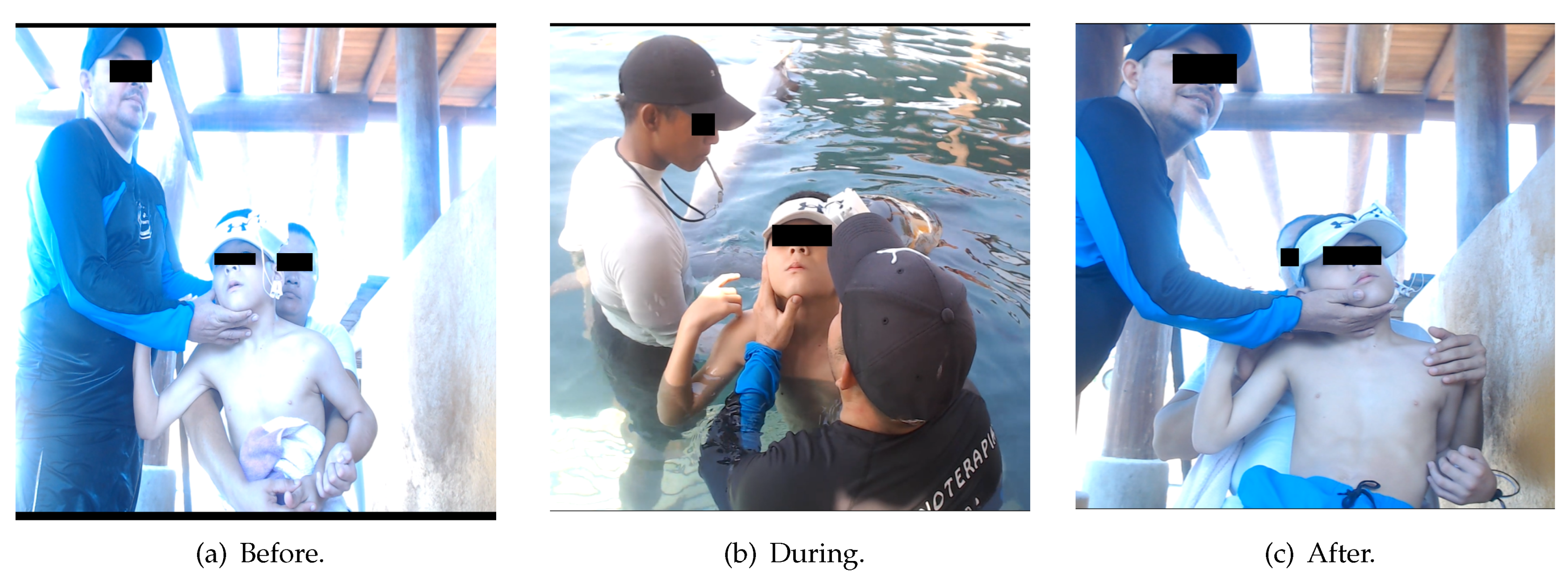

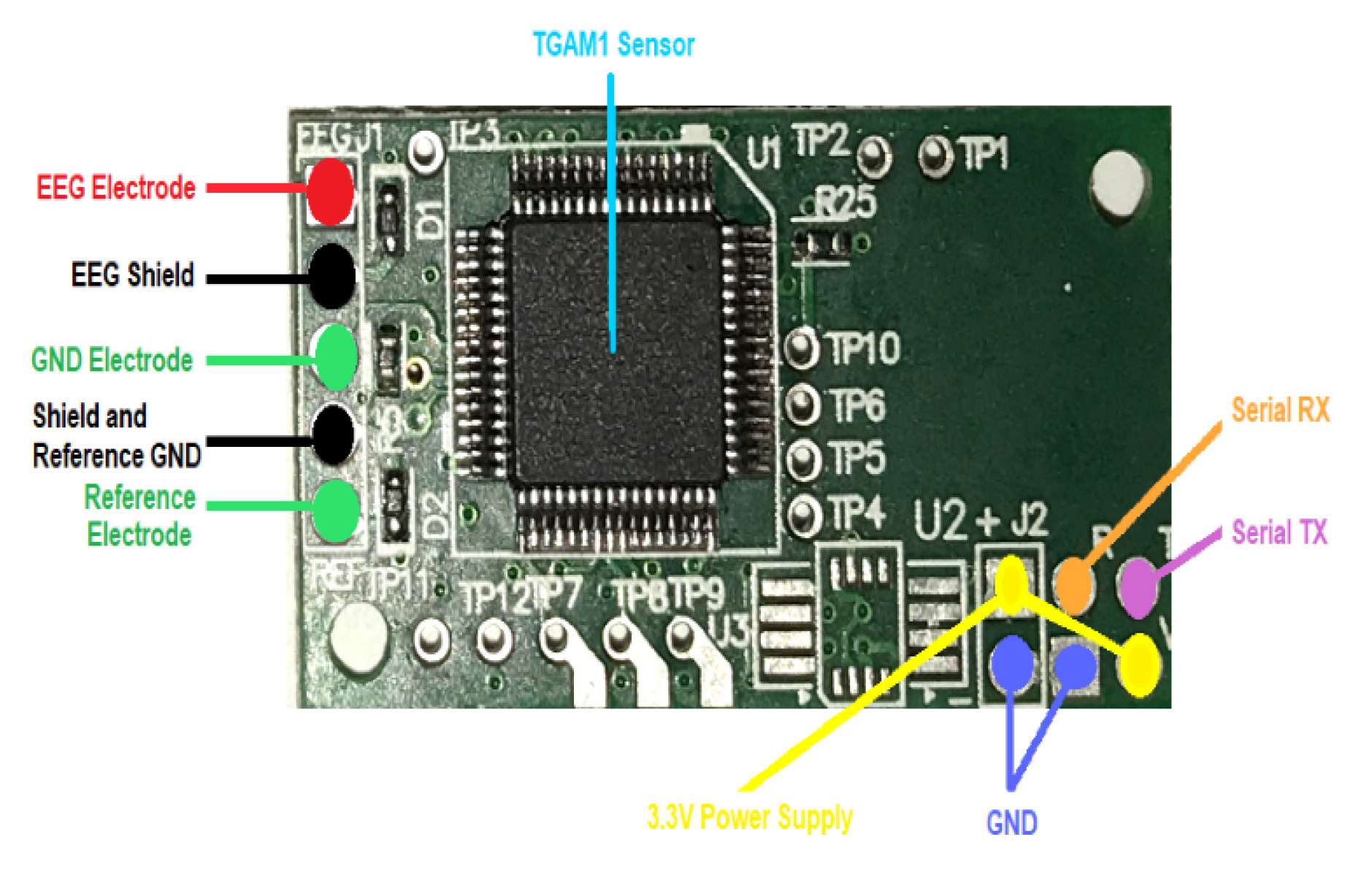

The experimental protocol involved the acquisition of EEG signals from 4 children diagnosed with cerebral palsy, all of whom underwent Dolphin-Assisted Therapy (DAT). It is important to mention that for all four subjects, as recorded on the frontopolar electrode in the forehead () using the TGAM1 module. The entire system was then segmented into three primary components.

A female bottlenose dolphin,

Intervention patients, specifically children with cerebral palsy, and

EEG device, sensor TGAM1, fig:TGAM1.

The interaction among the three subsystems is crucial in determining the efficacy of DAT in patients with cerebral palsy. In our analysis of EEG data, we decomposed the EEG signal into distinct functional frequency bands:

(0.5–4 Hz),

(4–8 Hz),

(8–12 Hz),

(12–30 Hz),

(30–60 Hz), and All Bands (0.5–60 Hz) by employing the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to estimate the Power Spectral Density (PSD), expressed in

[

18]. Subsequently, we investigated the behavior of the three patients with cerebral palsy using FFT on EEG signals [

19]. The RAW EEG data, which are time series representing cerebral brain activity (voltage versus time), were collected at three distinct intervals: i) At rest or

Before DAT or

, Figure 5a, ii)

During DAT or

, Figure 5b, and iii)

after DAT or

, Figure 5c. All time series of EEG signals, regardless of whether they were captured, were recorded using the first frontopolar electrode (

) with an TGAM1 EEG biosensor module, as shown in

Figure 4 [

20].

The methodology used in this research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Polytechnic Institute of Mexico, as indicated in the confidentiality commitment letter D/1477/2020. This document validates the procedures for sample collection and treatment given to bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) by the research team. In addition, this project ensured the ethical use of patient data, with participants fully informed and giving consent for the use of data collected during the experiments. Before sample collection and device attachment, participants were informed about the entire process; those who did not consent were allowed to withdraw immediately. Participants who agreed to the methodology and materials for sample collection signed a written informed consent form on January 25, 2020. In addition, participants were informed about the tests that would be performed on them, although some did not fully understand the details, before entering the tank with the cetaceans. The winter season was chosen to ensure that the temperature at noon during testing did not exceed 30ºC, while the measuring equipment was kept at temperatures not exceeding 20ºC. After sample collection, the adequacy of the data was evaluated; If found to be insufficient, participants were asked to remain in the tank for an additional sample collection, not exceeding 5 minutes.

Figure 5.

Method for obtaining EEG RAW samples.

Figure 5.

Method for obtaining EEG RAW samples.

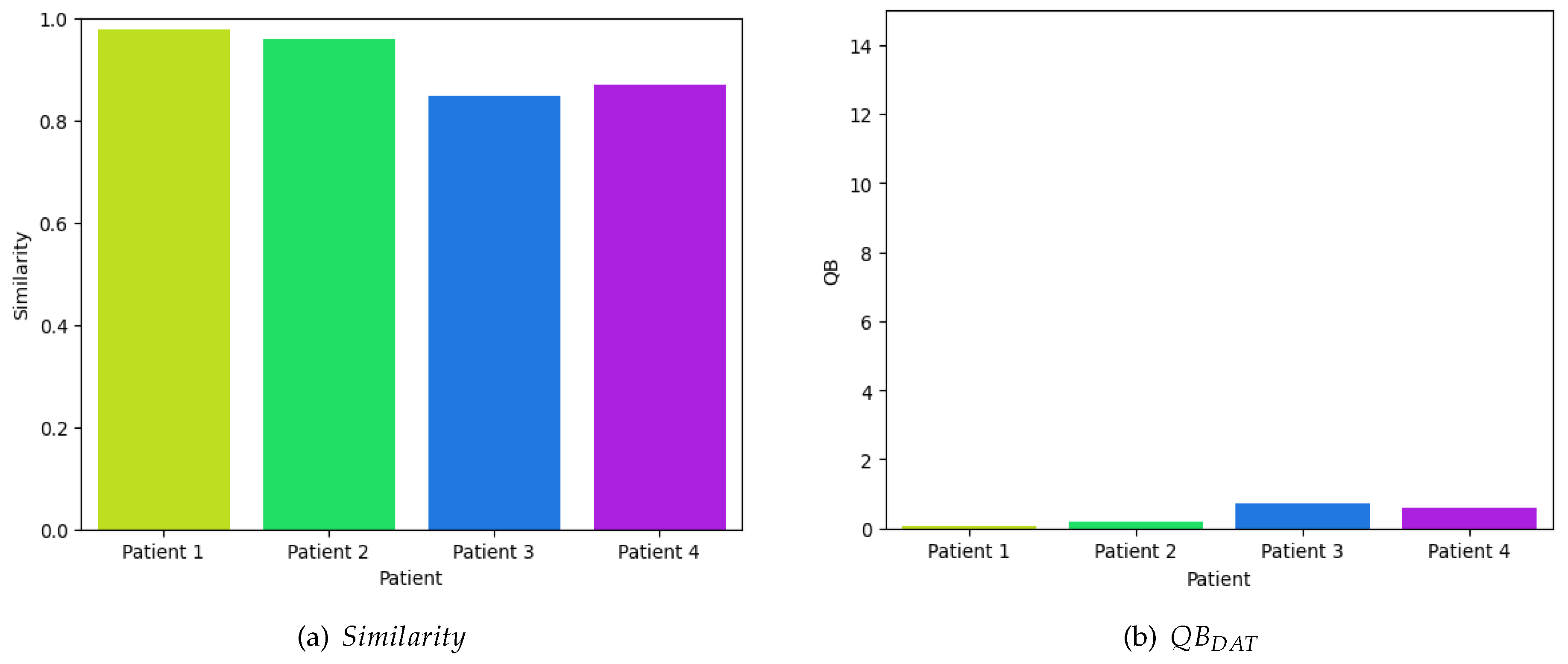

4.2. Discussion

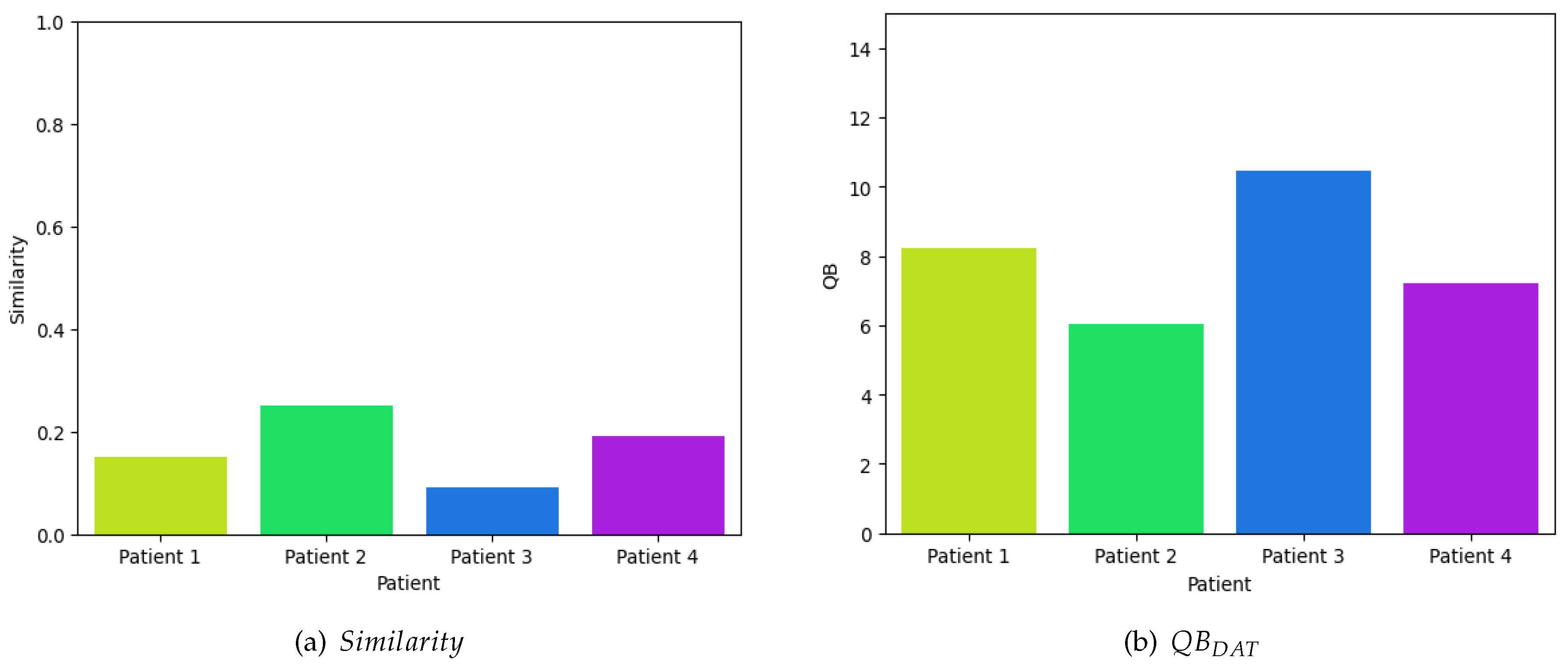

Initially, to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed model, four random samples were extracted from four children diagnosed with cerebral palsy. These samples exhibited an average similarity index of 0.9150, while the overall mean similarity across the entire database was 0.8753, . Figure 6a illustrates the similarity metrics of the samples in relation to the resting time series database, specifically those obtained before and after the children underwent dolphin-assisted therapy. These findings are anticipated because the samples are inherently expected to exhibit a high degree of similarity to the database.

Figure 6.

Quantitative Evaluation of the Efficiency of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy at Rest, i.e. .

Figure 6.

Quantitative Evaluation of the Efficiency of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy at Rest, i.e. .

Using Equation (7), as depicted in Figure 6b, it can be discerned that the perturbations in the neuronal voltage exhibit minimal variance, rendering them statistically insignificant and approaching null values, since we obtain on average 0.3939 dB of efficiency. This observation does not imply the ineffectiveness of dolphin-assisted therapy in activating specific cerebral regions; rather, the experiment is solely designed to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed model.

In contrast, to evaluate the efficacy of dolphin-assisted therapies, four random samples were obtained from four children diagnosed with cerebral palsy. These samples exhibited an average similarity index of 0.17, compared to a general mean similarity index of 0.2353 in all samples in the database . Figure 7a illustrates the similarity of these samples in relation to the time series database during dolphin-assisted therapy sessions, specifically when the child is involved in this alternative therapeutic intervention. The observed results indicate a low similarity with the database, suggesting that dolphin-assisted therapy induces distinct activity patterns compared to the typical activity of the patient.

Figure 7.

Quantitative Evaluation of the Efficiency During a Dolphin-Assisted Therapy, i.e. .

Figure 7.

Quantitative Evaluation of the Efficiency During a Dolphin-Assisted Therapy, i.e. .

Finally, by reapplying Equation (7), as depicted graphically in Figure 7b, it is evident that the disparities in neuronal voltage perturbations are substantial, resulting in a significant deviation from zero. This deviation suggests a marked difference from resting activity. The mean value of these four samples is 7.9825 dB, whereas the mean value across the entire dataset is 6.2838 dB. Consequently, this supports the assertion that dolphin-assisted therapy selectively activates specific regions of the brain exclusively during this unconventional therapeutic intervention.

5. Conclusions

Spastic cerebral palsy (SCP) represents the most prevalent subtype of cerebral palsy (CP), characterized by motor impairments attributable to early brain injury. Dolphin-assisted therapy (DAT) emerges as a promising adjunctive therapeutic modality for pediatric CP patients. This investigation examines the feasibility of employing a Siamese network as a biomarker to evaluate the efficacy of Dolphin-Assisted Therapy in children with Cerebral Palsy. The methodology encompasses the training of a simulative neural network (SNN), a specialized neural network architecture designed to assess input similarities, utilizing data procured from CP patients participating in DAT sessions. The study’s outcomes reveal encouraging results, demonstrating distinct patterns in SNN outputs that correlate with symptomatic improvements in CP following DAT. These findings underscore the potential applicability of SNNs as an objective and quantifiable means for evaluating therapeutic interventions. Ultimately, it is clear that the variations in neuronal voltage fluctuations are considerable, leading to a notable deviation from zero. This deviation indicates a significant difference from resting state activity. The average value of these four samples is 7.9825 dB, while the average value for the entire dataset is 6.2838 dB. Therefore, this supports the claim that dolphin-assisted therapy specifically activates certain brain regions only during this unique therapeutic approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Y.A.V.; formal analysis, H.Q.E. and E.Y.A.V.; investigation and resources, O.M.M.; data acquisition, J.J.M.E. and E.Y.A.V.; writing original draft preparation, L.C.H., J.J.M.E., and O.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article is supported by National Polytechnic Institute (Instituto Poliécnico Nacional) of Mexico by means of projects No.

Acknowledgments

The research described in this work was carried out at Escuela Superior de Ingeniería Mecánica y Eléctrica along with Centro de Investigación en Computación of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Campus Zacatenco.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cans, C.; others. Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2007, 49, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durkin, M.; others. Prevalence and correlates of cerebral palsy among children in Botswana. Journal of the American Medical Association 2000, 284, 1971–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, D.; others. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveillance Summaries 2014, 63, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelmann, K. ; others. The changing panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden. IX International Cerebral Palsy Conference, 2009.

- Odding, E.; others. Epidemiology of cerebral palsy: prevalence, impairments and risk factors. Disability and Rehabilitation 2006, 28, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.; others. The definition and classification of cerebral palsy: an historical perspective. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2007, 49, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskoui, M.; others. Cerebral palsy and developmental coordination disorder in children born at term. Paediatrics & Child Health 2013, 18, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Johnson, A. Assistive devices for children with physical disabilities. Pediatric Physical Therapy 2010, 20, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Deng, Z. Siamese neural networks for continuous speech emotion recognition in ambulatory settings. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 2018, 46, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalan, K.; Raja, K. Siamese Neural Network for Drug–Drug Interaction Extraction from Biomedical Text. Journal of Healthcare Engineering 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, B.K.; Desai, N. Siamese Neural Network Based Clustering for Anomaly Detection in Healthcare Data. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 18190–18201. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, G.; Zemel, R.; Salakhutdinov, R. Siamese Neural Networks for One-shot Image Recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2015, pp. 152–158. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, C. Siamese Convolutional Neural Networks for Healthcare Image Analysis. 2019 IEEE 18th International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), 2019, pp. 1119–1124. [CrossRef]

- Parodi, R.; Kooij, R.E. Siamese Neural Network-based Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring. 2019 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM).

- Wang, J.; Feng, J. Siamese Neural Network for Biomedical Image Registration. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164668–164679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, P.; Cruz, T. Siamese Neural Networks for Biosignal Classification: Application to Sleep Stage Scoring. 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2018, pp. 2106–2109. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Park, J. Siamese Neural Networks for Medical Diagnosis with Uncertainty Estimation. International Conference on Neural Information Processing, 2019, pp. 390–399. [CrossRef]

- Kantelhardt, J.; Tismer, S.; Gans, F.; Schumann, A.; T. , P. Scaling behavior of EEG amplitude and frequency time series across sleep stages. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 2015, 112, 18001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtahi, F.; Ro, T.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z. Emotion Analysis Using Audio/Video, EMG and EEG: A Dataset and Comparison Study. 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2018, pp. 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Senevirathna, B.; Abshire, P. Spatio-temporal compressed sensing for real-time wireless EEG monitoring. 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), 2018, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).