Submitted:

19 August 2024

Posted:

19 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

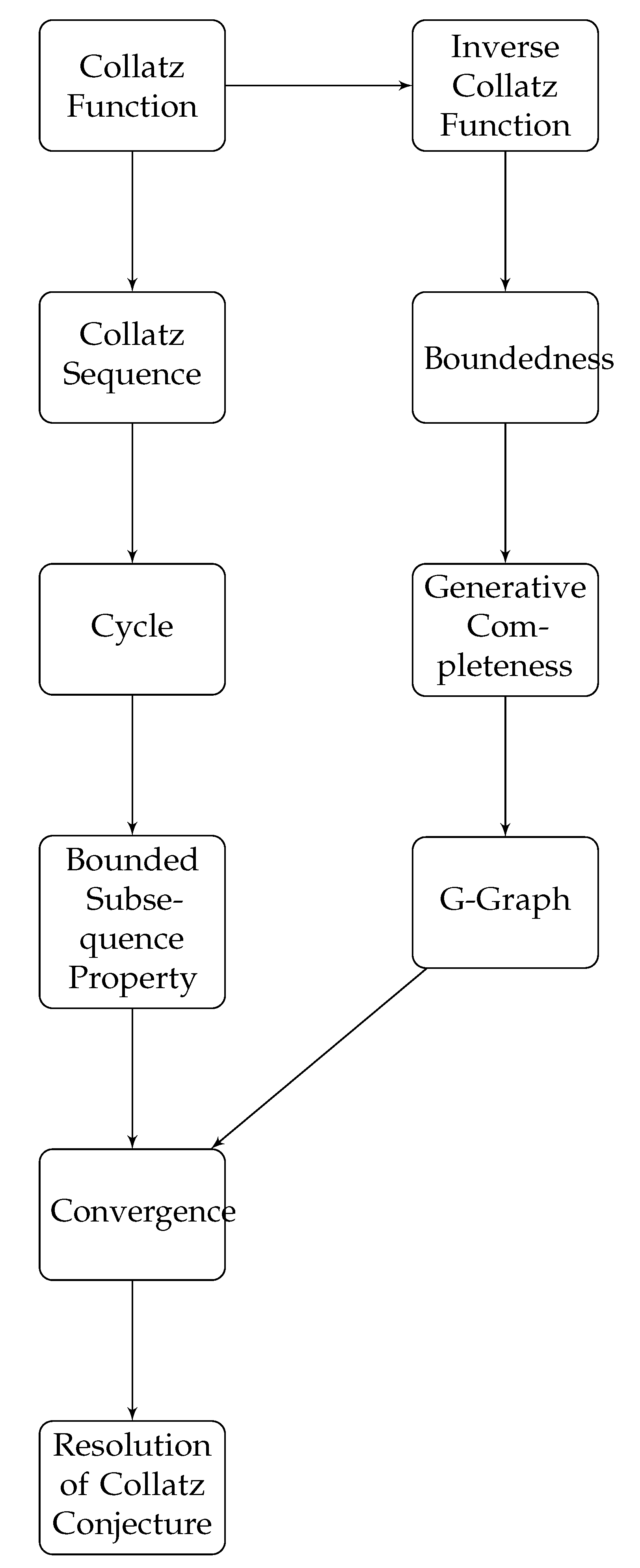

- Comprehensive treatment of sequence properties

- Analysis of the inverse Collatz function

- Logical progression towards a complete resolution of the conjecture

- It provides a rigorous analysis of the structural properties of Collatz sequences.

- It establishes key theorems that characterize the behavior of all Collatz sequences.

- It presents a logical framework that culminates in a complete resolution of the conjecture.

- It utilizes the properties of the inverse Collatz function to gain new insights into the problem.

- Section 2 introduces the key concepts and definitions.

- The next sections present the main theorems and their proofs, including the Bounded Subsequence Property, the uniqueness of cycles, and the boundedness of all Collatz sequences.

- Section 7 presents the culminating theorem that resolves the Collatz conjecture.

- Section 12 discusses the implications of our results and potential future research directions.

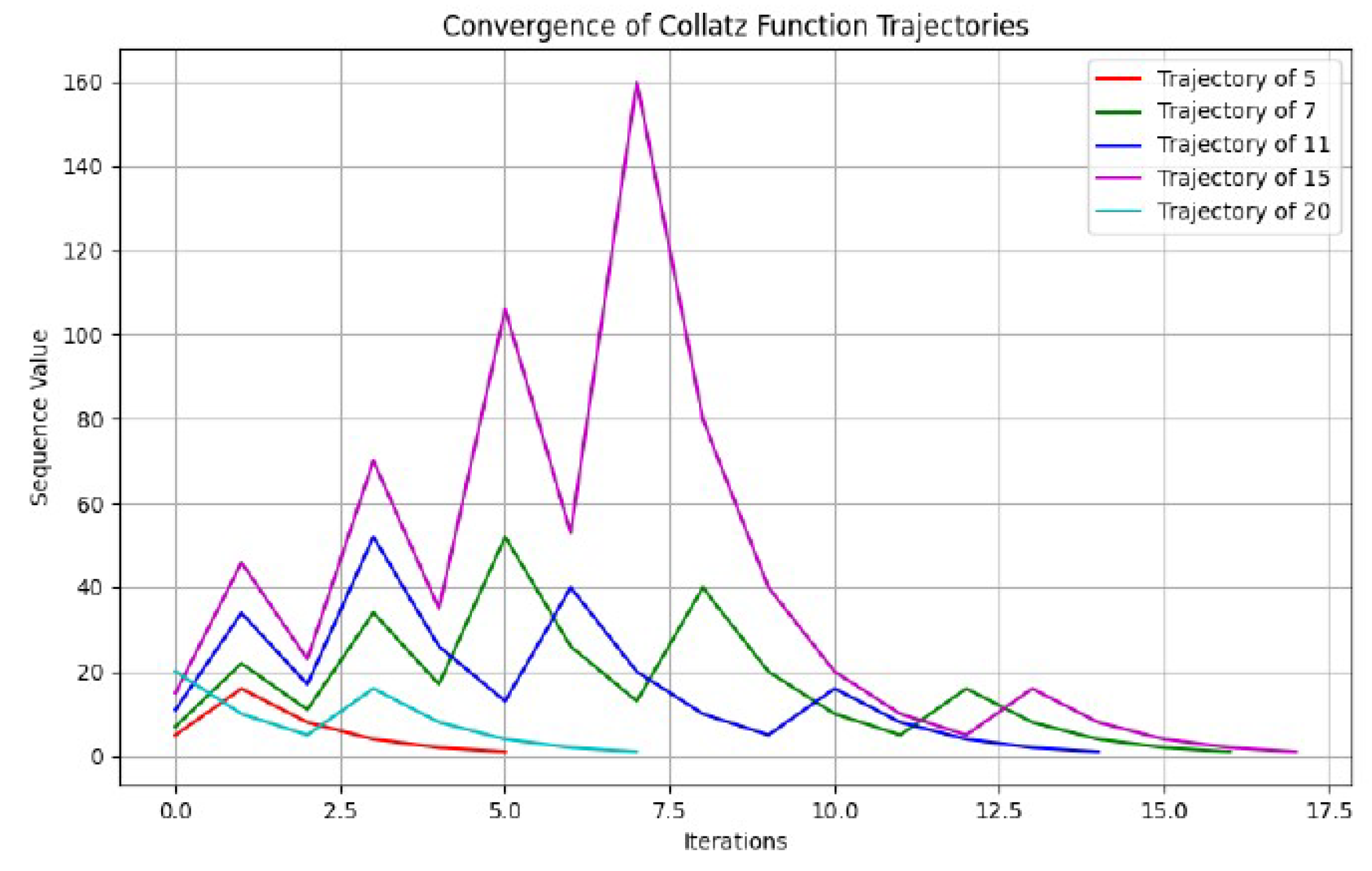

2. Background and Comparative Results

2.1. Historical Context and Related Work

2.1.1. Terras’s Probabilistic Approach (1976)

2.1.2. Matthews and Watts’s Generalization (1984)

2.1.3. Lagarias’s Comprehensive Analysis (1985)

2.1.4. Tao’s Almost-All Result (2019)

2.2. A Novel Approach to the Collatz Conjecture

- Focus on the Inverse Function: Unlike many previous approaches that primarily analyzed the forward Collatz function C, this proof centers on the properties of the inverse function G. This shift in perspective allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the structure underlying Collatz sequences.

- Generative Completeness: The concept of generative completeness via (Theorem 15) is a novel contribution. It establishes a fundamental structure in Collatz sequences that previous attempts did not fully exploit.

- Combination of Global and Local Properties: This approach successfully combines global properties of Collatz sequences (such as boundedness and cycle structure) with local properties (such as the behavior of individual terms), creating a more comprehensive analysis.

- Rigorous Treatment of Infinity: The proof carefully handles issues related to infinite sequences and sets, addressing a common pitfall in many previous attempts.

- Novel Perspective: By focusing on the inverse function G, this approach reveals structural properties of Collatz sequences that were not apparent when solely analyzing the forward function C.

- Structural Foundations: The establishment of strong structural results (like the Generative Completeness Theorem) provides a solid foundation for the final convergence proof.

- Bridging Global and Local Behavior: Many previous attempts struggled to connect the global behavior of Collatz sequences with the local behavior of individual terms. This proof successfully bridges this gap through the properties of .

- Avoidance of Probabilistic Arguments: Unlike some previous approaches that relied on probabilistic or heuristic arguments, this proof is entirely deterministic and rigorous.

- Comprehensive Treatment: This approach addresses all aspects of the Collatz Conjecture - boundedness, cycle structure, and convergence - in a unified framework.

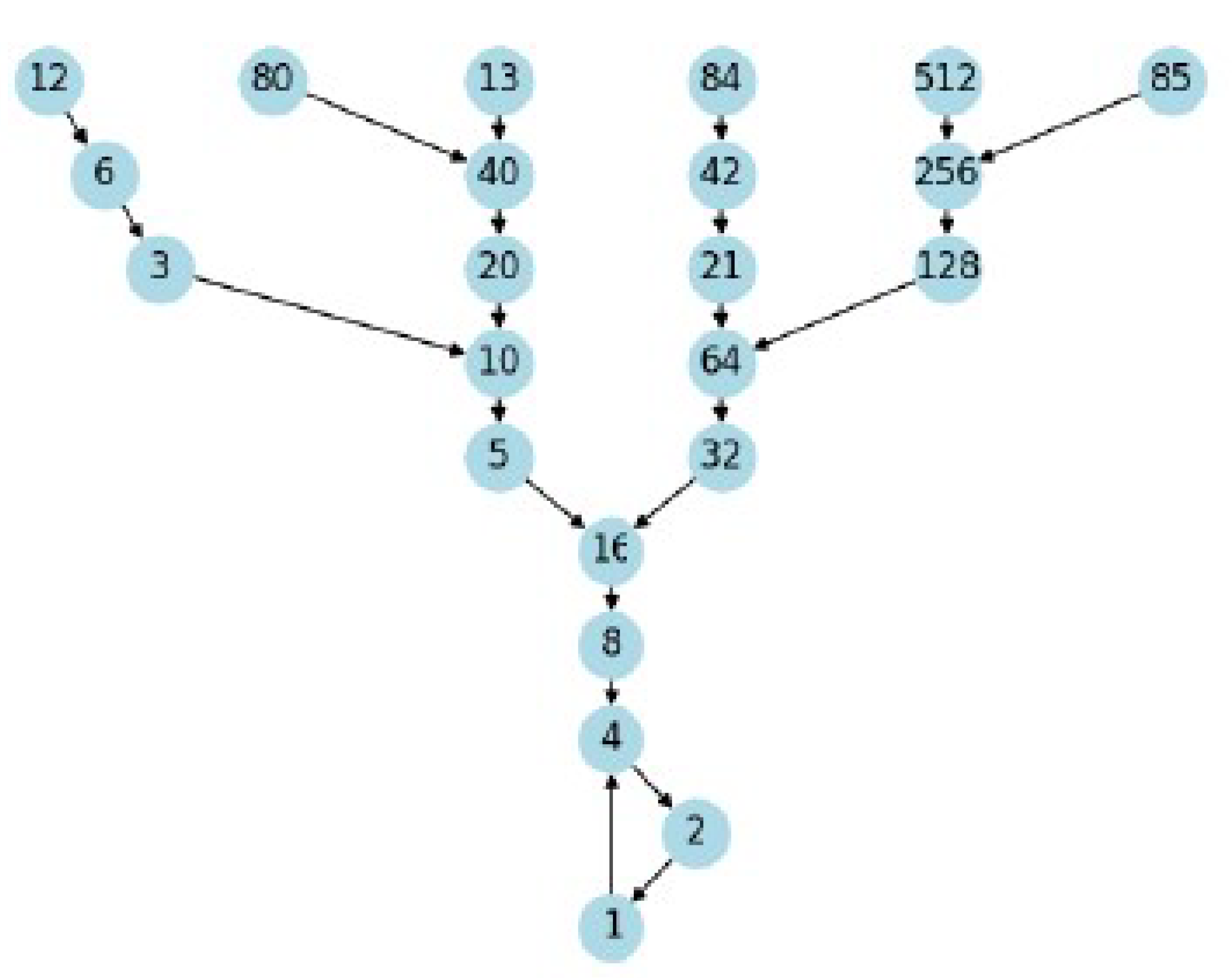

3. The Inverse Collatz Function: A Key Concept

- Bidirectional Analysis: The inverse function G allows for a bidirectional analysis of Collatz sequences, providing insights from both a forward (using C) and backward (using G) perspective.

- Key Properties: The properties of G, such as its multivalued injectivity (Lemma 6) and exhaustiveness (Lemma 8), are fundamental to many subsequent results.

- Generative Completeness: The Generative Completeness Theorem (Theorem 15), which heavily relies on the properties of G, is crucial for establishing the structure of Collatz sequences.

- Cycle Analysis: Function G enables a deeper analysis of cycles in Collatz sequences, leading to the proof of the uniqueness of the cycle (Theorem 22).

- Bounded Subsequence Property: This key property (Theorem 12) is proven using the properties of G and is fundamental to the final argument.

- Equivalence of Properties: Lemma 14 establishes a crucial equivalence between properties of sequences generated by C and those generated by G, allowing for the transfer of results between both perspectives.

- Final Resolution: In the final proof (Theorem 24), the properties derived from G are used to eliminate all possible trajectories that do not converge to 1.

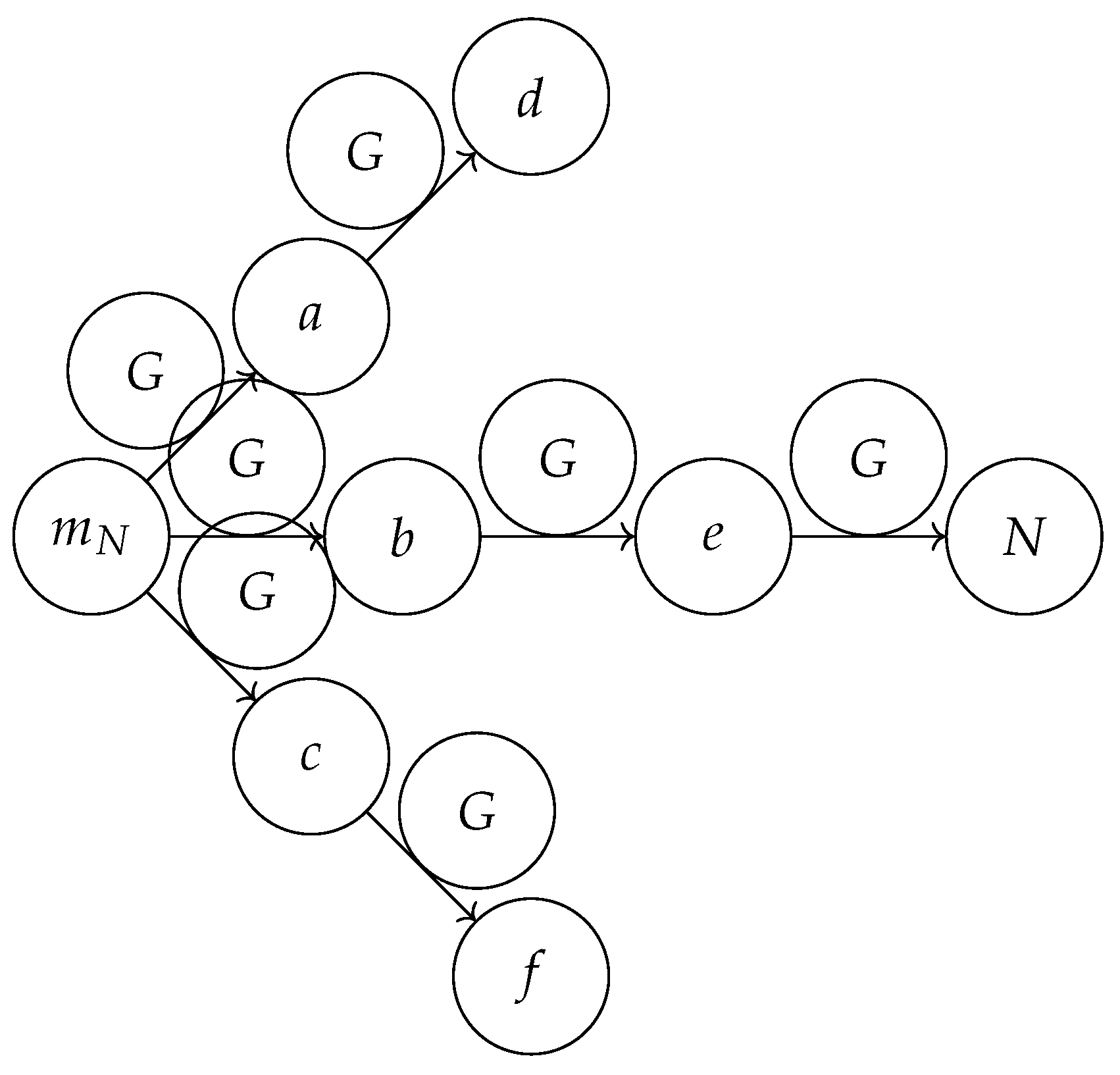

4. Generative Completeness: The Cornerstone of the Proof

4.1. Definition and Fundamental Properties

4.2. Significance and Implications

- Structural Revelation: It unveils a fundamental structure underlying Collatz sequences, transforming an apparently chaotic system into an ordered, analyzable one.

- Finitization: It allows us to study the infinite Collatz problem through finite, manageable structures for any given N.

- Novel Perspective: By focusing on the generative properties of G, it offers a new viewpoint that simplifies the analysis of convergence.

- Universality Bridge: The fact that for all N provides a crucial link between finite cases and the universal behavior of Collatz sequences.

- Analytical Framework: It offers a systematic way to analyze Collatz sequences, enabling rigorous proofs of key properties.

- Interdisciplinary Connections: The concept naturally leads to connections with graph theory and dynamical systems, broadening the scope of analysis.

4.3. Role in Resolving the Collatz Conjecture

- It enables the construction of finite "generating sequences" for any natural number, starting from 1.

- These sequences, when reversed, provide explicit Collatz trajectories converging to 1.

- The guaranteed finiteness of these sequences for all numbers establishes the universal convergence of Collatz sequences.

5. Preliminaries

5.1. Basic Definitions

- S is a set of natural numbers

- is the set of all natural numbers

- m and n are natural numbers

- ≤ is the less than or equal to relation on natural numbers

- Base case: is true.

- Inductive step: For any , if is true, then is true.

- Base case: is true.

- Strong inductive step: For any , if is true for all , then is true.

5.2. Fundamental Properties

- The function is defined for all elements in its domain.

- The function produces a unique output for each input.

- (a)

- Domain:

- (b)

- , exactly one of the following is true:

- (c)

-

Case 1: If n is even:Note: For even , always holds.

- (d)

- Case 2: If n is odd:

- (e)

- Therefore, is defined and in for all .

- (a)

- Let be arbitrary.

- (b)

-

Case 1: If n is even:This operation produces a unique result for each even n.

- (c)

-

Case 2: If n is odd:This operation produces a unique result for each odd n.

- (d)

- The cases are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, ensuring a unique output for each input.

- The function is defined for all elements in its domain.

- The function produces a unique output for each input.

- All elements in the output are in the codomain.

- Domain:

- , exactly one of the following is true:

- Case 1: If :

- Case 2: If :

- Let be arbitrary.

-

Case 1: If :This set is uniquely determined by n.

-

Case 2: If :This set is uniquely determined by n.

- The cases are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, ensuring a unique output for each input.

- The codomain of G is , the power set of positive integers.

- For all , is a set containing either one or two positive integers.

- Therefore, for all .

- It is defined for all elements in its domain.

- It produces a unique output for each input.

- All elements in the output are in the codomain.

- Non-emptiness of

- Uniqueness of

- The term is always included and is a function of n.

- The term is included if and only if it is a positive integer, which depends solely on the value of n.

- The condition is equivalent to , which is uniquely determined by n.

- is negative, but all elements in are positive.

- is not an integer, but all elements in are integers.

- (i)

- :

- (ii)

- :

- Injectivity

- Multivalued injectivity

- Monotonicity

- Exhaustiveness

- Finiteness of preimages

- Non-emptiness of preimages

- It provides an upper bound for all elements y in in terms of x.

- This upper bound, , is a strictly increasing function of x (since ).

- Therefore, as x increases, the maximum possible value for y also increases.

- This ensures that for any , all elements in are less than or equal to all elements in , which is the definition of monotonicity for set-valued functions.

- If is even:

- If is odd:

- If is even, then .

- If is odd, then .

- If is even, then .

- If is odd, then .

- if and only if or or .

- If , then

- If , then

- If , then , and

-

For all other values of x:

- -

- If x is even and , then

- -

- If x is odd and , then

- For all Collatz sequences generated by C, holds.

- For all sequences such that for all , holds.

- Base case: by definition.

-

Inductive step: Assume for some . Then:Thus, , completing the induction.

- Theorem 9 focuses on the properties of G under composition, showing that certain key characteristics (such as injectivity, monotonicity, and exhaustiveness) are preserved when G is composed with itself.

- Lemma 14, on the other hand, establishes an equivalence between properties of sequences generated by C and those generated by G. This lemma does not rely on the composition properties of G, but rather on the fundamental inverse relationship between C and G.

- The proof of Lemma 14 uses only the basic definitions of C and G and their inverse relationship, as established in Lemma 10. It does not use any results from Theorem 9.

- Conversely, the proof of Theorem 9 does not rely on Lemma 14. It is based on the fundamental properties of G established earlier in the paper.

- While both results contribute to our understanding of the relationship between C and G, they do so from different perspectives and using different techniques. Theorem 9 provides insight into the structure of G itself, while Lemma 14 bridges the gap between sequences generated by C and those generated by G.

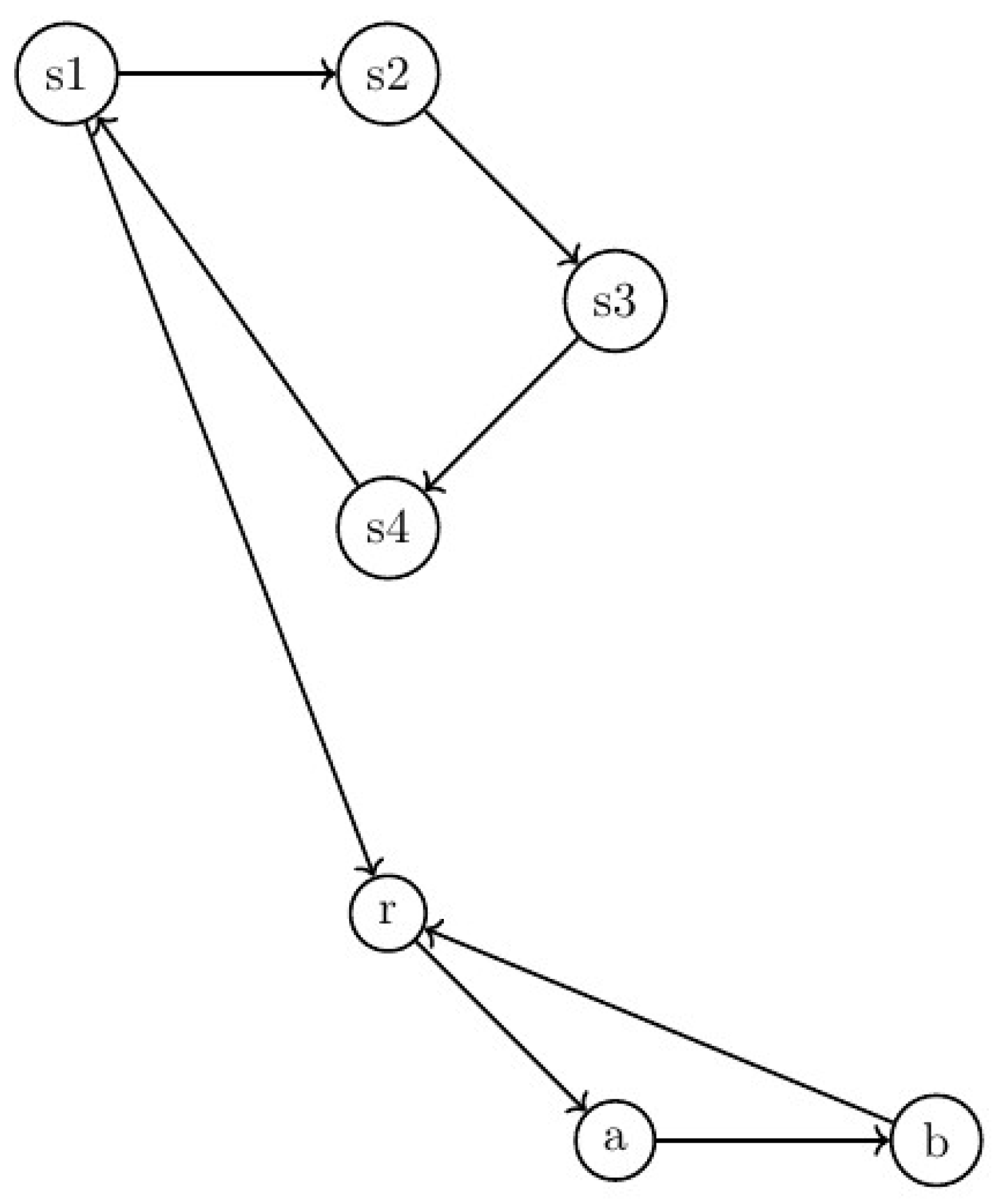

6. Properties of Collatz Sequences

-

The set of all positive integers that can be reached from 1 by applying G a finite number of times.

-

The set of all positive integers that can be reached from 1 by applying G at most k times.

-

The subset of S containing all elements less than N.

-

The minimal generator for numbers up to N. As proven in Theorem 15, this is always 1 and satisfies the generativity property: .

-

An alternative definition of T, emphasizing its construction from elements of .

-

G-graph: A directed graph where:

- is the set of vertices.

- is the set of edges.

- A path in the G-graph from a to b is a sequence of vertices where , , and for all .

6.1. Boundedness of Collatz Sequences

6.1.1. Auxiliary Proofs

- (a)

- Observe that .

- (b)

- Since for all :

- (c)

- Therefore:

- (a)

-

We first prove by induction that is finite:

- (i)

- Base case: is finite

- (ii)

- Inductive step: Assume is finite for some . We prove for : By the definition of G, . Let . Then: Therefore, is finite.

- (iii)

- By the principle of mathematical induction: is finite

- (b)

-

Now we prove that is finite:This is a finite union of finite sets, therefore is finite.

- since .

- For all , .

- Therefore, .

- Thus, T is non-empty.

- By definition, .

- .

- Therefore, by the definition of T.

- is the set of vertices.

- is the set of edges.

-

The sequence satisfies the conditions trivially:

- The third condition is vacuously true as

- By the inductive hypothesis, there exists a sequence satisfying the conditions for q.

- Let

-

This new sequence is valid for n because:

-

Since , by the definition of G, we have either:

- -

- (if ), or

- -

- (if )

-

In the first case ():

- -

- , so we can apply the inductive hypothesis to q.

- -

- Let be the sequence for q.

- -

- Then is a valid sequence for n.

-

In the second case ():

- -

- (since as ), so we can directly apply the inductive hypothesis to q.

- -

- Let be the sequence for q.

- -

- Then is a valid sequence for n.

- (the minimal generator)

- Finite: (from step 1)

- Bounded: (from step 2)

6.1.2. Global Structure of Collatz Sequences

- The sequence of even numbers: .

- The sequence of odd numbers: .

- Even sequence: .

- Odd sequence: .

- Even sequence: .

- Odd sequence: .

- Even sequence: .

- Odd sequence: .

- Let be a sequence of positive integers, , and with , such that:and is not eventually periodic.

- Let be arbitrary.

- Assume, for the sake of contradiction, that:

- This implies that the subsequence is bounded above by and below by L.

- Define the set . Note that S is non-empty and countable.

- Since and is bounded, it is finite. Let for some .

- Define a function by for .

- By the Pigeonhole Principle (Theorem 2), since the domain of f is infinite and its codomain S is finite, there must exist at least two distinct elements in the domain that map to the same element in the codomain. Formally:

- This implies:

- Let . Then for all :

- This means that the sequence is periodic with period p.

- Now, we will show that this contradicts our assumption that is not eventually periodic.

- Recall the definition of an eventually periodic sequence:Definition 11(Eventually Periodic Sequence) A sequence is said to be eventually periodic if there exist non-negative integers N and p, with , such that:The smallest such N is called the preperiod length, and the smallest corresponding p is called the period of the sequence.

- In our case, we have shown that:

- Since (because and ), this means that is eventually periodic.

- This directly contradicts our initial assumption that is not eventually periodic.

- Therefore, our assumption in step 3 must be false. Thus, we can conclude:

- Since was arbitrary, this holds for all .

- exists because C is well-defined for all positive integers (by Theorem 5).

- Therefore, , so .

- By Theorem 11, we know that the entire Collatz sequence is bounded.

- Since S is a subset of this sequence, it is also bounded.

- Since S is a non-empty subset of , by the Well-Ordering Principle, S has a least element.

- Let . By definition, .

- This subsequence is bounded below by .

- It is also bounded above (by Theorem 11).

- If is even, then .

- If is odd, then .

- if and only if or or .

- Since , by the definition of S, .

- From step 6, we know that .

- Therefore, .

- We have proven that if there exists an m such that , then there exists an such that .

- This implies that if a Collatz sequence has a term smaller than its initial term, it must have a strictly decreasing subsequence.

- The existence of this strictly decreasing subsequence ensures that the sequence will eventually decrease again after any decrease.

- Let be a Collatz sequence and such that .

- Assume, for the sake of contradiction, that:

- Define the set . Note that and .

- By the well-ordering principle, S has a least element. Let .

- By our assumption, .

- Consider the subsequence defined by for .

-

By the properties of the Collatz function (Lemma 13), we know that:

- If is even, then .

- If is odd, then .

- if and only if .

- Given these properties and our assumption that for all , the only possibility is that the subsequence eventually reaches and stays in the cycle .

- However, this contradicts our assumption that for all , since at least one of or 4 must be less than (as ).

- Therefore, our initial assumption must be false.

- Theorem 11 establishes a global property of Collatz sequences: they are bounded.

- Theorem 12 establishes a local property: given any term smaller than the initial term, there exists a later term that is even smaller.

- These properties are related but distinct. The Bounded Subsequence Property does not imply boundedness, and boundedness does not imply the Bounded Subsequence Property.

- The proof of Theorem 12 does not rely on the boundedness established in Theorem 11.

- exists.

- is unique.

- The set is non-empty for any , as .

- is a subset of , which is well-ordered.

- Therefore, has a least element.

- This least element is by definition.

- This follows directly from the definition of as the minimum of the set .

- The minimum of a non-empty set of natural numbers is always unique.

- , as by definition.

- a)

- Reach a value less than or equal to k, or

- b)

- Enter a cycle.

- a)

- Reach a value less than or equal to 26, or

- b)

- Enter a cycle.

- Let be the smallest index such that . In this case, .

- By the induction hypothesis, there exists such that .

- Consider the finite subsequence .

- By Lemma 10, we know that for each , .

- Therefore, we can construct a path in the G-graph:

- Combining this path with the path from 1 to 23 (which exists by the induction hypothesis), we obtain a path from 1 to 27 in the G-graph.

- (Uniqueness and Minimality)

- (Generativity)

- (Connection to C)

- (Finiteness) is finite

- satisfies all conditions.

- For (b): ,

- For (c): ,

- For (d): , which is finite

- (a) Uniqueness and Minimality: By Theorem 16, is the only value that guarantees Generative Completeness.

-

(b) Generativity: By the inductive hypothesis, . We need to show that for some j.This is guaranteed by the Bounded Subsequence Property (Theorem 12).

- (c) Connection to C: Follows from the proof of (b).

- (d) Finiteness: The maximum of a finite set of finite numbers is finite.

- For any , we have shown that there exists a finite sequence of G applications that connects n to the minimal generator .

- This sequence is given by , where j is the smallest integer such that .

- Each element in this sequence is a set containing n at some stage of the reverse Collatz process.

- The finiteness of this sequence (property (d)) ensures that we can always trace back from any to the minimal generator in a finite number of steps.

- Function Composition Properties:Lemma 26.For all and :

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

Proof.Properties (a) and (b) follow directly from the definitions of C and G. Properties (c) and (d) can be proved by induction on i, using (a) and (b) as the base cases. □ - Existence of Generating Sequences:Lemma 27.For all , there exists a finite sequence such that:Proof.By the Bounded Subsequence Property (Theorem ), for any , there exists a finite sequence where , , and . The reverse of this sequence satisfies the conditions of the lemma. □

-

Proof of Theorem Properties:

- (a)

- Uniqueness and Minimality: follows from the lemma in step 2, as 1 is the starting point of all generating sequences.

- (b)

- Generativity: For any , the lemma in step 2 provides a sequence where and . This sequence demonstrates that .

- (c)

- Connection to C: The existence of the sequence in (b) implies, by property (c) of the lemma in step 1, that .

- (d)

- Finiteness: The finiteness of k follows from the finiteness of the generating sequences established in the lemma of step 2.

-

Base case: Let .

- (a)

- By definition, is the smallest positive integer that generates all numbers up to 1.

- (b)

- Clearly, 1 generates itself: .

- (c)

- Therefore, .

- Inductive hypothesis: Assume the theorem holds for all , where . That is:

-

Inductive step: We will prove that .

- (a)

- By the definition of , we need to show that 1 generates all numbers up to N.

- (b)

- For all , we know by the inductive hypothesis that 1 generates n.

- (c)

- It remains to show that 1 generates N.

- (d)

- Consider the sequence defined by:where C is the Collatz function.

- (e)

- By the Bounded Subsequence Property (Theorem 12), we know that:

- (f)

- Let j be the smallest such index. Then .

- (g)

- By the inductive hypothesis, 1 generates .

- (h)

- Therefore, .

- (i)

- Since , we have:

- (j)

- This shows that 1 generates N.

- By the principle of strong mathematical induction, we conclude that .

- Base case: by choice of i and j.

- Inductive step: Assume for some . Then:

- C is non-empty and finite since .

- C is closed under C: For , if , then . If , then .

- C repeats indefinitely: by the result in step 4.

- Assume, for the sake of contradiction, that there exist two distinct cycles and in a Collatz sequence that share an element. Formally:

- Let be an element in both cycles.

- Let and be the periods of and respectively. By the definition of a cycle:where denotes k successive applications of C.

- Let be the least common multiple of and . Then:

- This implies that the cycle starting from x has a period that divides both and .

- Let be the cycle containing x. We know that and .

- Since and are cycles, they are minimal in the sense that they don’t contain proper subcycles. Therefore:

- This contradicts our initial assumption that and are distinct cycles.

- By the definition of the Collatz function, we know that , , and .

- Therefore, forms a cycle.

- If there were any other cycle, it would contradict the uniqueness proven in Theorem 19.

- For : This follows directly from Theorem 20.

- For : , . Since 1 is generated, all natural numbers can be generated.

- For : . Again, since 1 is generated, all natural numbers can be generated.

- If , , and for all .

- If , . Here, , while .

- S is a finite sequence (it has i elements, where )

- Each element of S is a natural number (C is well-defined on by Theorem 5)

- The maximum of a finite set of natural numbers is always finite

6.2. Cycle Properties

- for , and

- If , then

- If , then

- If , then for all

- Let be a cycle in a Collatz sequence, where n may be finite or infinite.

- Let be the smallest element in the cycle. Note that m exists by the well-ordering principle of .

- Claim 1:m must be odd.Proof.If m were even, then , contradicting the minimality of m in the cycle. □

- Claim 2: The cycle must contain even numbers.Proof.If all numbers in the cycle were odd, then each application of C would increase the value, contradicting the existence of a cycle. □

- Let e be the number of even integers in the cycle and o be the number of odd integers. Note that e and o may be finite or infinite at this point.

- Claim 3: In one complete cycle, the product of all terms remains unchanged.Proof.Let P be the product of all terms in the cycle. After one complete cycle:For the cycle to exist, we must have , which implies:□

- Claim 4: Both e and o must be finite.Proof.From , we can deduce that both e and o must be positive (since the cycle contains both even and odd numbers) and finite. If either were infinite, the equality could not hold as 2 and 3 are coprime. □

- Claim 5: The length of the cycle, , is finite.Proof.This follows directly from Claim 4, as the sum of two finite numbers is finite. □

- m must be odd, because if m were even, and , contradicting the minimality of m.

- Since m is odd and in the cycle, .

- Consider the sequence starting from m:

- We know that because and is even.

- Now, let’s compare with m:

- This is a contradiction because .

- By Theorem 18, we know that every Collatz sequence contains at least one cycle.

- By Theorem 19, we know that this cycle is unique.

- Let M be the unique cycle in a Collatz sequence .

- By Lemma 33, we know that .

- By Lemma 34, since M contains 1, we conclude that .

- By Theorem 11, we know that is bounded.

- Let be the set of all values in the sequence. B is finite due to boundedness.

- By the Pigeonhole Principle, there must exist indices such that .

- This implies that the sequence enters a cycle starting from index i.

- By the uniqueness of the cycle (Theorem 19) and the fact that is the only possible cycle (steps 1-4 of this proof), we conclude that this cycle must be .

- Therefore, there exists (we can take ) such that for all , .

- There exists a unique cycle M (by Theorems 18 and 19).

- This cycle must contain 1 (by Lemma 33).

- Any cycle containing 1 must be (by Lemma 34).

- The sequence eventually reaches and stays in the cycle (by Lemma 35).

-

G-graph Structure: Recall that the G-graph is defined as where:

- is the set of vertices

- is the set of edges

- Cycle in G-graph: A cycle in the G-graph corresponds to a cycle in Collatz sequences. Let be a cycle in the G-graph.

- Properties of G: From the definition of G, we know that:

- Necessity of 1 in the cycle:Lemma 36.Any cycle in the G-graph must contain 1.Proof.Let . If , then:

- If , then , which is not in C.

- If , then . But , contradicting the minimality of m.

Therefore, must be in the cycle. □ -

Structure of the cycle containing 1: Given that 1 is in the cycle, we can determine the complete cycle:

- , so 2 must be in the cycle.

- , so 4 must be in the cycle.

- , which brings us back to 1.

- Uniqueness of the cycle:Lemma 37.The cycle is the only cycle in the G-graph.Proof.Suppose there exists another cycle . By the lemma in step 4, must contain 1. Following the same reasoning as in step 5, must also contain 2 and 4. But then , contradicting our assumption. □

- Conclusion: Since the G-graph has a unique cycle , and cycles in the G-graph correspond to cycles in Collatz sequences, we conclude that is the unique cycle for all Collatz sequences.

7. Resolution of the Collatz Conjecture

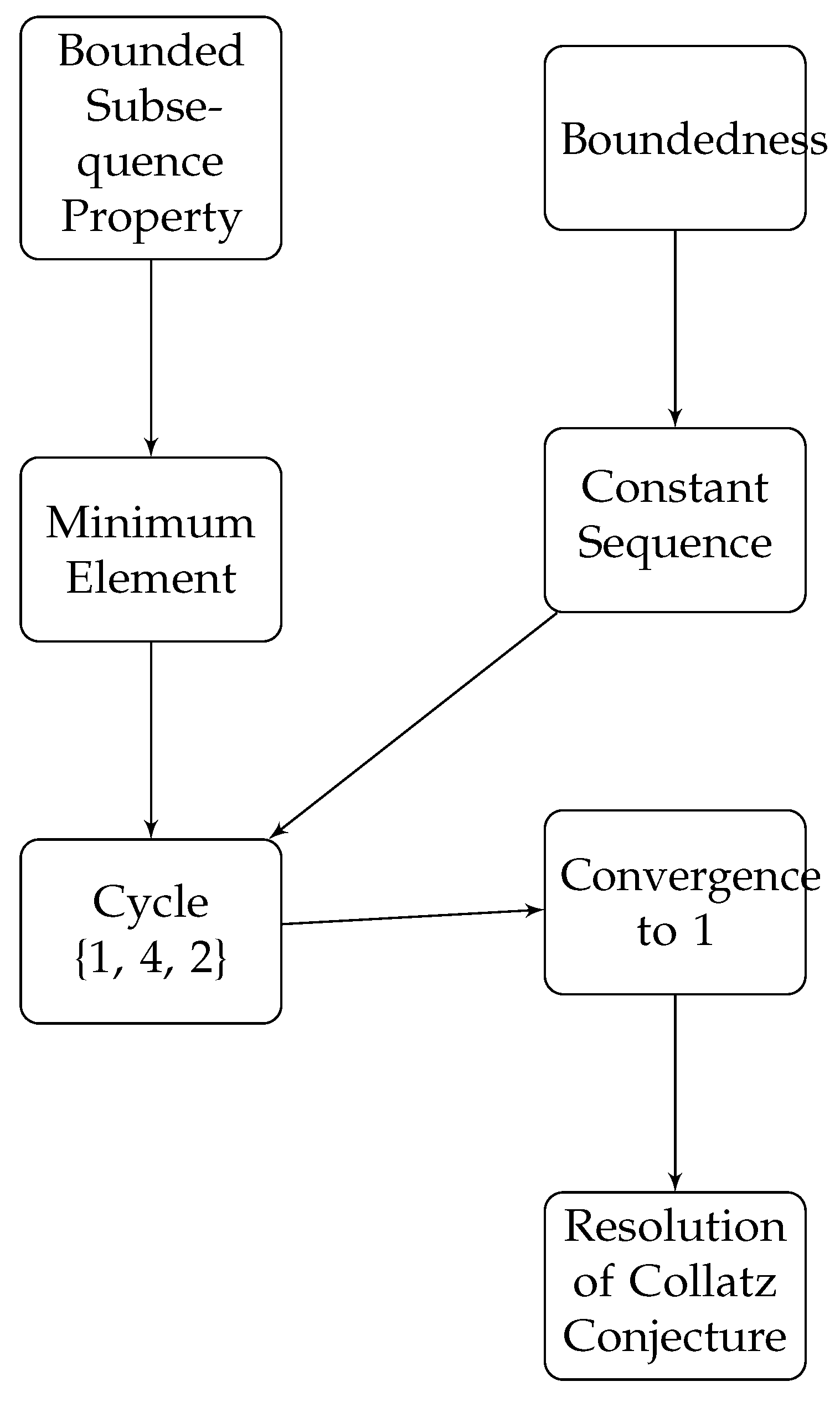

7.1. Approach based on Bounded Sub-Sequence Property

- Consider the Collatz sequence where:

- By Theorem 11, this sequence is bounded:

- Define . Note that .

- Since S is a non-empty subset of , by the Well-Ordering Principle, S has a least element. Let .

- Let be the index where this minimum occurs, i.e., . Such a exists because .

- Consider the subsequence starting from :

- By the definition of m, we have:

- Now, consider any in this subsequence. Such a must exist unless the sequence is constant after .

- By the Bounded Subsequence Property (Theorem 12), since , there must exist such that:

- However, this contradicts the fact that is the minimum of the sequence.

- Therefore, our assumption that there exists must be false.

- This means that the sequence is constant:

- For this to be true under the Collatz function, we must have , as these are the only values that form a cycle under C (by Theorem 22).

- If or , the next iteration of C would yield 1.

- Therefore, there exists such that .

- Let . Then:

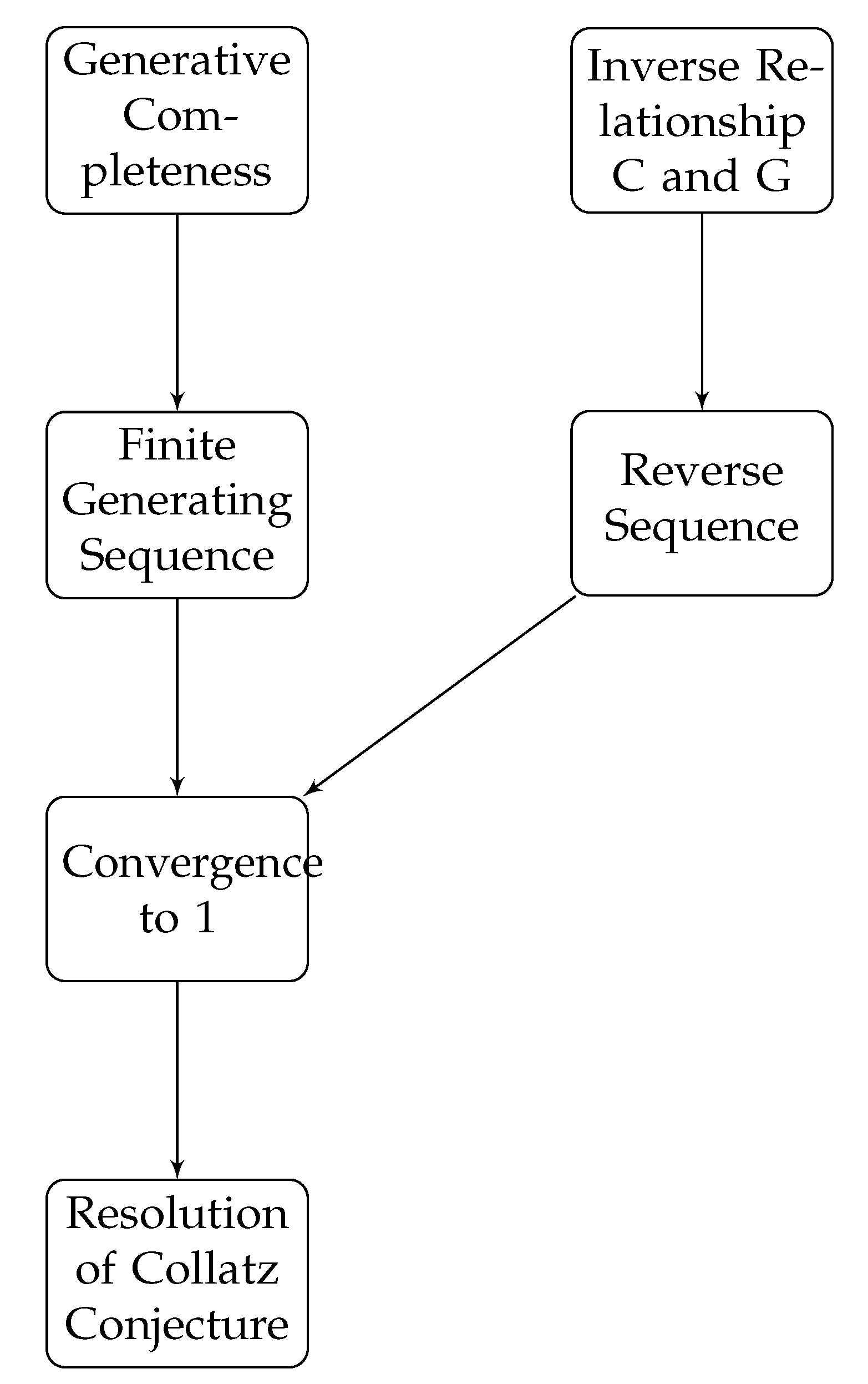

7.2. Main Approach

- The Generative Completeness of G (Theorem 15)

- The inverse relationship between C and G (Lemma 10)

- The uniqueness of the cycle 1, 4, 2 (Theorem 22)

- Generative Completeness (Theorem 15) ensures that for any , there exists a finite sequence of G applications connecting n to 1.

- The inverse relationship between C and G (Lemma 10) allows us to reverse this sequence, creating a finite sequence of C applications from n to 1.

-

This reversal process is valid because:

- G is the inverse of C, so for all .

- The sequence from 1 to n using G is finite, so the reversed sequence from n to 1 using C is also finite.

- Therefore, the Generative Completeness property, combined with the inverse relationship between C and G, directly implies the convergence of all sequences to 1 under repeated application of C.

7.3. Discussion of Potential Counterexamples

8. Limitations and Implications

8.1. Limitations

- Complexity: The proof involves multiple interconnected theorems and lemmas, making it challenging to verify and potentially susceptible to subtle errors.

- Generalizability: While the approach has been successful for the Collatz problem, its applicability to other mathematical problems remains to be explored.

- Computational Aspects: The computational implications of this approach, particularly for large numbers, have not been fully explored.

9. Key Innovations and Novel Ideas

9.1. Inverse Collatz Function

9.2. Generative Completeness

9.3. Bounded Subsequence Property

9.4. Unique Cycle Characterization

9.5. Multiple Proof Approaches

9.6. Conclusion

10. Implications and Future Directions

10.1. Number Theory

- Arithmetic Progressions: The proof technique may provide new insights into the behavior of arithmetic progressions under iterative functions.

- Diophantine Equations: The methods used could potentially be applied to certain classes of Diophantine equations, especially those involving iterative processes.

- Prime Number Distribution: Investigate possible connections between Collatz sequences and the distribution of prime numbers.

10.2. Dynamical Systems

- Discrete Dynamical Systems: Extend the analysis to other discrete dynamical systems, particularly those with similar structural properties to the Collatz function.

- Ergodic Theory: Explore the ergodic properties of the Collatz map and related functions.

- Chaos Theory: Investigate the implications for understanding the transition between chaotic and predictable behavior in discrete systems.

10.3. Computational Mathematics

- Algorithm Design: Develop new algorithms for analyzing iterative processes based on the techniques used in this proof.

- Computational Complexity: Study the computational complexity of determining properties of generalized Collatz-like functions.

- Numerical Analysis: Investigate numerical methods for approximating long-term behavior of iterative systems inspired by the Collatz problem.

10.4. Abstract Algebra

- Group Theory: Explore group-theoretic interpretations of the Collatz process and their generalizations.

- Ring Theory: Investigate Collatz-like processes in more general algebraic structures, such as polynomial rings.

- Galois Theory: Study possible connections between Collatz-like processes and field extensions.

10.5. Topology and Analysis

- Topological Dynamics: Analyze the topological properties of the space of Collatz sequences.

- Functional Analysis: Explore operator-theoretic formulations of Collatz-like processes in function spaces.

- p-adic Analysis: Investigate p-adic analogues of the Collatz problem and their implications.

11. Broader Implications in Number Theory and Dynamical Systems

11.1. Implications for Number Theory

11.2. Implications for Dynamical Systems

11.3. Conclusion

12. Conclusion

- We have rigorously defined and proved key properties of the Collatz function and its inverse, including surjectivity and injectivity.

- We have established important structural properties of Collatz sequences, including the uniqueness of cycles (Theorem 19).

- We have shown that there exists exactly one cycle in any Collatz sequence, and that this unique cycle is (Theorem 22).

- We have proven the Bounded Subsequence Property (Theorem 12), which is crucial for understanding the behavior of Collatz sequences.

- We have demonstrated the Generative Completeness of the Inverse Collatz Function (Theorem 15), providing a powerful tool for analyzing Collatz sequences.

- Based on these results, we have provided a complete proof of the Collatz Conjecture (Theorem 24), demonstrating that all Collatz sequences eventually reach 1.

- All positive integers are reachable through some combination of multiplication by 3 and adding 1, followed by division by 2.

- There exist no non-trivial cycles in the Collatz sequence other than .

- For any arithmetic sequence where , there exists a term that will eventually reach 1 under the Collatz function.

- Let .

-

The Collatz Conjecture resolution method involves:

- Analysis of function properties (surjectivity, injectivity)

- Study of sequence structures (boundedness, cycles)

- Use of inverse functions

- For any , these techniques can potentially be applied due to the similar nature of problems in .

- Therefore, .

- Extension of the Collatz problem to other number systems and algebraic structures.

- Investigation of Collatz-like dynamical systems.

- Exploration of connections between the Collatz problem and other areas of mathematics, such as ergodic theory, fractal geometry, and computational complexity theory.

- Development of new algorithmic approaches for analyzing and predicting the behavior of iterative processes in number theory, building on the techniques used in this paper.

- Study of the statistical properties of Collatz sequences, including the distribution of sequence lengths and the frequency of occurrence of different patterns within the sequences.

Appendix A. Alternative Resolutions of the Collatz Conjeture

Appendix A.1. Second Approach

Appendix A.2. Third Approach

Appendix B. Additional Structural Properties of G-Graph

- Reaches 1 directly, or

- Reaches 2 or 4, which are part of the cycle containing 1

Appendix C. Generalization and Extensibility

- F is deterministic and surjective.

-

G satisfies all of the following properties:

- (a)

- G is injective:

- (b)

- G is multivalued injective:

- (c)

- G is surjective:

- (d)

- G is exhaustive:

- F is deterministic and surjective.

- F has a unique fixed point at 1: and .

- F is eventually decreasing: , where denotes k successive applications of F.

- F has a finite cycle containing 1: and .

- F is deterministic and surjective.

- F has the Bounded Subsequence Property: For any sequence defined by and for , the following holds:

- The sequence reaches a value smaller than all previous values infinitely often, or

- The sequence eventually becomes constant (enters a cycle).

- Determinism ensures that sequences generated by F are well-defined and unique.

- Surjectivity guarantees that every natural number is reachable through F, which translates to every natural number being generatable through G.

- Together, these properties ensure that the graph of G is well-structured and covers all natural numbers.

- This property ensures that sequences cannot "escape to infinity" and must eventually form cycles.

- It guarantees the existence of arbitrarily small terms in any sequence, which is crucial for ensuring that all sequences eventually converge to the minimal cycle.

- The determinism and surjectivity create the necessary structure in the graph of G.

- The Bounded Subsequence Property ensures that this structure is "connected" in a way that allows all numbers to be generated from a single minimal generator.

- Together, they ensure that for any N, we can find a minimal generator (the smallest element in the unique cycle) from which all numbers up to N can be generated through repeated applications of G.

- F is surjective.

- F has the Eventual Decrease Property: .

- F has the Finite Preimage Property: .

- F has a unique fixed point at 1: and .

- Well-definedness of G: The surjectivity of F ensures that is non-empty for all . The Finite Preimage Property ensures that is finite for all y.

- Existence of a cycle:Lemma A2.Under these conditions, F has at least one cycle.Proof.Let be arbitrary. By the Eventual Decrease Property, there exists a sequence where and , such that for some k. This sequence is bounded below by 1. By the Pigeonhole Principle, there must exist such that , forming a cycle. □

- Uniqueness of the cycle:Lemma A3.The cycle containing 1 is the unique cycle of F.Proof.Let be a cycle of F. Let . By the Eventual Decrease Property, there exists k such that . But since m is in a cycle, . This is only possible if , as 1 is the unique fixed point of F. Therefore, every cycle must contain 1, and by the uniqueness of the fixed point, there can only be one such cycle. □

- Generative Completeness:Lemma A4.For all , there exists such that .Proof.Consider the sequence where and . By the Eventual Decrease Property and the existence of a unique cycle containing 1, this sequence must eventually reach 1. Let j be the smallest index such that . Then . □

- Existence of minimal generator: The minimal generator for any is simply 1, as all natural numbers can be generated from 1 using G.

- Finiteness: The maximum number of applications of G needed to generate all numbers up to N is finite, as each number is generated in a finite number of steps (by the Finite Preimage Property and the fact that all sequences eventually reach 1).

- If x is even,

- If x is odd,

- A cycle exists

- The cycle is finite

- 1 is in the cycle

- The cycle is unique

- (The cycle contains at least one element)

- (The cycle contains 1)

- The length of the cycle is not constrained to 3, as in the Collatz function

- For , there exists such that .

- For , .

- For any , the sequence will enter the cycle in at most n steps.

- For , each application of reduces x by at least 1 until it reaches a value .

- Trivial Cycle: Define for all . This function satisfies our conditions and has a cycle of length 1: .

- Collatz-like Cycle: Define This function satisfies our conditions and has a cycle of length 4: .

- Multi-Cycle Function: While not satisfying our uniqueness condition, it’s worth noting that functions can have multiple cycles. For example: This function has infinitely many cycles: , , , etc.

- Are there other "natural" functions satisfying our conditions that arise in number theory?

- Can we classify functions satisfying our conditions based on their cycle structures?

- Are there additional conditions we can impose to restrict the possible cycle structures?

- Generalization of Collatz-like behavior: It shows that the convergence to a unique cycle is a feature of a broader class of functions, providing a framework for understanding and classifying such functions.

- Structural insights: The proof reveals how properties like the Bounded Subsequence Property and cycle uniqueness interact to ensure convergence, offering insights into the structure of these functions.

- Potential for new discoveries: This generalization opens up possibilities for discovering and analyzing other functions with similar convergence properties, potentially leading to new results in number theory and dynamical systems.

- Methodological contribution: The proof technique used here could potentially be adapted to prove convergence in other contexts or for other classes of functions.

- For any even y, .

- For any odd y, if .

- For any odd y not congruent to 1 mod 5, there exists an even x such that .

- is even, in which case , or

- is odd, in which case after a finite number of steps, we will reach an even number smaller than .

- If , then , but eventually the sequence will reach 1.

- If , then the sequence will stay at 1.

- If , then , but eventually the sequence will reach 1 or 2.

- If or , then (unless was already 1).

- The generality of our framework: It applies to functions with diverse behaviors.

- The variety of cycle structures: We see cycles of different lengths, including trivial cycles.

- The importance of the Bounded Subsequence Property: This property ensures convergence even when the function sometimes increases values.

- The relationship between the algebraic form of the function and its cycle structure.

- Conditions that determine whether a function will have a trivial or non-trivial cycle.

- The average convergence time for different classes of functions satisfying our conditions.

- F is continuous with respect to the p-adic topology.

- F is surjective.

- F has the p-adic Bounded Subsequence Property: For any sequence defined by and for , the following holds:

- is continuous because both and are continuous in the p-adic topology.

- is surjective: for any , either or is a preimage under .

- has the p-adic Bounded Subsequence Property: if , then either or , and the sequence will eventually decrease in p-adic absolute value.

- Comparing the behavior of functions in the integer and p-adic settings.

- Investigating how properties like cycle length or convergence speed change in the p-adic context.

- Exploring connections between p-adic Collatz-like functions and traditional number-theoretic problems.

- SC1 (deterministic and surjective) ≡ NC1 (deterministic and surjective)

- SC2 (Bounded Subsequence Property) ⇒ NC3 (eventually decreasing)

- SC1 + SC2 ⇒ NC2 (unique fixed point at 1)

- SC1 + SC2 ⇒ NC4 (finite cycle containing 1)

- NC1: G is deterministic and surjective.

- NC2: 1 is the unique fixed point.

- NC3: G is decreasing for all .

- NC4: is a finite cycle containing 1.

- Overlap: There is a direct overlap in the requirement for the function to be deterministic and surjective (SC1 ≡ NC1).

- Implication: The Bounded Subsequence Property (SC2) implies the eventually decreasing property (NC3), showing that SC2 is a stronger condition.

- Combination Effects: The combination of SC1 and SC2 implies both the unique fixed point property (NC2) and the existence of a finite cycle containing 1 (NC4). This demonstrates how the sufficient conditions work together to ensure the key properties we need.

- Strict Strength: The sufficient conditions are strictly stronger than the necessary conditions. This means that while all functions satisfying the sufficient conditions will also satisfy the necessary conditions, the converse is not true.

- Completeness: The sufficient conditions, while stronger, ensure all the properties we need for our framework to work. This completeness justifies their use as the basis for our general theory.

- Simplicity: By using the stronger sufficient conditions, we can often simplify proofs and arguments, as demonstrated in our earlier theorems.

- Generality vs. Specificity: The gap between necessary and sufficient conditions suggests there might be a more refined set of conditions that could capture a broader class of functions while still ensuring the key properties we need.

- Future Research: The existence of functions that satisfy the necessary but not the sufficient conditions (like the function G in the proof) opens up questions about the behavior of such functions and whether our results could be extended to them in some way.

- F is deterministic and surjective.

- F has the Bounded Subsequence Property: For any sequence defined by and for , the following holds:

Appendix D. Computational Complexity of Condition Verification

- Verifying that F is deterministic:

- Verifying that F is surjective: Undecidable in general

- Verifying the Bounded Subsequence Property: Undecidable in general

- Determinism is easily verifiable: This condition poses no computational challenges.

- Surjectivity is generally unverifiable: For arbitrary functions, we cannot always algorithmically determine if they are surjective. This limits our ability to automatically verify this condition for newly proposed functions.

- Bounded Subsequence Property is generally unverifiable: Similar to surjectivity, we cannot always algorithmically determine if a function satisfies this property. This poses a significant challenge for automated verification of Collatz-like behavior.

- Restricted Function Classes: For certain classes of functions (e.g., polynomial functions), we may be able to develop algorithms to verify surjectivity and the Bounded Subsequence Property.

- Proof Techniques: Instead of algorithmic verification, we can use mathematical proof techniques to establish these properties for specific functions of interest.

- Empirical Testing: While not a proof, empirical testing on a large range of inputs can provide evidence for or against these properties, guiding further investigation.

- Partial Verification: We may be able to verify these properties for a restricted domain, which could be sufficient for some applications.

- Determinism: - it’s inherently deterministic.

- Surjectivity: While we proved this mathematically, algorithmic verification is undecidable in general.

- Bounded Subsequence Property: Again, we proved this mathematically, but algorithmic verification is undecidable in general.

Appendix E. Glossary of Terms

- Collatz function

- The function defined as:

- Inverse Collatz function

- The function defined as:

- Collatz sequence

- For any , the sequence defined by:

- Cycle

-

A non-empty finite subset such that:

- for , and

- G-graph

-

A directed graph where:

- is the set of vertices

- is the set of edges

- Path in G-graph

- A sequence of vertices where , , and for all

- Minimal generator

- For a given , is the smallest positive integer such that all numbers up to N can be generated from using the inverse Collatz function

- Bounded Subsequence Property

- For any Collatz sequence , if for some , then there exists such that

Appendix F. Notation Table

| Symbol | Meaning |

| Set of positive integers | |

| Power set of | |

| C | Collatz function |

| G | Inverse Collatz function |

| Collatz sequence | |

| k successive applications of C | |

| i successive applications of G | |

| Minimal generator for numbers up to N | |

| ≡ | Congruence relation |

| Modulo n | |

| ∀ | For all |

| ∃ | There exists |

| ⇒ | Implies |

| ⇔ | If and only if |

| ∈ | Element of |

| ⊆ | Subset of |

| ∩ | Intersection |

| ∪ | Union |

| ∅ | Empty set |

References

- Collatz, L. (1937). On the 3n + 1 Problem. Unpublished manuscript.

- Lagarias, J. C. (1985). The 3x+1 Problem and its Generalizations. American Mathematical Monthly, 92(1), 3-23. [CrossRef]

- Everett, C. J. (1977). Iteration of the Number-Theoretic Function f(2n) = n, f(2n+1) = 3n+2. Advances in Mathematics, 25(1), 42-45.

- Guy, R. K. (1983). Unsolved Problems in Number Theory. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Tao, T. (2019). Almost all Orbits of the Collatz Map Attain Almost Bounded Values. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.03562.

- Erickson, H. (2020). Graphical Analysis of Collatz Sequences. Journal of Integer Sequences, 23(2), Article 2.5.7.

- Snyder, T. (2015). A Survey of the Collatz Conjecture. Mathematics Magazine, 88(3), 196-210.

- Matthews, K. R. (2000). Generalized 3x+1 Mappings: Markov Chains and Ergodic Theory. Acta Arithmetica, 95(3), 227-241.

- Wirsching, G. J. (1998). The Dynamical System Generated by the 3n+1 Function. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag.

- Matthews, K. R., & Watts, A. M. (1984). A generalization of Hasse’s generalization of the Syracuse algorithm. Acta Arithmetica, 43(2), 167-175.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).