1. Introduction

As we all know, population increases and economic growth naturally provoked increases in energy consumption [

1]. Today, 70–80% of all energy produced in the world comes from fossil fuels, such as natural gas, oil and coal [

2] and at the same time the cost of hydrogen synthesis is too high. As fossil fuel reserves decline, dependence on renewable energy has become crucial, while the continued use of fossil fuels leads to considerable environmental and economic costs. The increasing costs of our current energy systems highlight the potential of hydrogen proton-exchange membrane fuel cells as a viable alternative to internal combustion engines, though they require a reliable H

2 supply [

3]. Consequently, having a liquid hydrogen source that can provide H

2 on demand is beneficial, with hydrogen production from methanol via steam reforming over copper-based catalysts emerging as a notable method.

Currently, hydrogen is indispensable due to its efficient and clean properties as an energy carrier [

4]. The most used process in production organizations is steam reforming, which, in turn, involves the decomposition of molecules of hydrocarbons, alcohols, in particular methanol and ethanol, using superheated steam. The result of which is hydrogen and carbon oxides. But these processes are energy-consuming, since they take place at high temperatures and, in addition to the target products, produce a large number of undesirable accompanying and by-products. Alternatively, hydrogen can be synthesized using the process of electrolysis of water [

5] (which breaks down into O

2 and H

2) - a less cost-effective method due to the amount of electricity required for electrolysis. The approach we propose can completely or partially solve all these problems. This method requires only an inexpensive catalyst and a mixture of methanol and water.

Under much milder conditions, catalytic processes of steam reforming of aliphatic alcohols take place, which, moreover, can be obtained from renewable raw materials - biomass (bioalcohols). Compared to gaseous hydrogen carriers, methanol, an affordable hydrocarbon liquid hydrogen carrier (a low-carbon alcohol) with high hydrogen content, can react with water to release H

2 under relatively mild conditions. This is due to methanol's lack of a strong C-C bond, unlike other multi-carbon hydrocarbon resources [

6]. Steam reforming of methanol (SRM) seems attractive because the process is characterized by low energy costs and relatively cheap raw material itself [

7], in addition to traditional methods, is combined with a wide range of alternative sources for methanol synthesis [

8]:

- biomass (agricultural waste, timber);

- household waste with a high organic content;

- waste gases from enterprises.

Their gasification will make it possible to obtain a gas mixture for the subsequent synthesis of methanol along the “green” route, without using fossil organic fuel. Most likely, in the near future, alternative sources of methanol synthesis in the form of biogas will become one of the few solutions to energy supply problems in the world. It is no secret that reserves of natural hydrocarbons are being depleted every year and this direction may well become the only variable method of producing both motor fuel and petrochemical products.

A promising direction for using the resulting methanol is its use as a motor fuel for internal combustion engines and fuel cells. Compared to traditional fuels, methanol has a number of advantages such as renewability, smaller carbon footprint and high calorific value [

9]. All of them are the main drivers of demand for methanol for use as a raw material and energy carrier in hydrogen production. It is expected that by 2030, methanol production in the world will exceed 130 million tons per year.

The SRM process involves following chemical reactions:

Reactions (1) and (2) are endothermic and reversible, accompanied by an increase in volume, while the exothermic reaction (3) without a change in volume is known as a water gas shift reaction [

10]. As a result, a mixture of hydrogen and carbon oxides is formed, the ratio between which depends on the process conditions and the nature of the catalyst.

A development of a new effective catalyst for the process of steam reforming of methanol into hydrogen-containing gas is aim of this work, which will contribute to the further development of a new environmentally friendly, energy-saving method for hydro-gen production.

Bulk metals [

11,

12] and oxides [

13,

14] as well as supported ones on various types of carriers [

15] are used as catalysts for the conversion of hydrocarbons. However, in the recent years, new types of highly active catalysts made in the combustion process have appeared. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) [

16] and in particular its modern modification – solution combustion synthesis (SCS) [

17,

18,

19] is a new method for obtaining a modern class of catalysts of various uses based on metals, alloys, oxides, spinels, etc. The mode of a strong exothermic reaction (combustion reaction), in which the heat release is localized in the layer and transferred from layer to layer by heat transfer is carried out in the SHS process. Structures with a high concentration of defects, which are one of the reasons for the high activity of SCS catalysts, are formed under conditions of rapid rates of combustion and cooling reactions. Studies of the physicochemical and mechanical properties of a wide range of synthesized SHS and SCS catalysts were reported in the literature [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. As a result of these studies, SHS materials with high catalytic activity, promising for many industrial processes, such as partial oxidation, reduction, carbon dioxide conversion of methane, etc., were developed [

27,

28]. In this study a series of catalysts based on Cu, Ce and Al was synthesized by SCS and traditional impregnation methods and characterized by a range of physico-chemical methods. The catalysts were investigated in methanol steam reforming in a continuous fixed bed reactor.

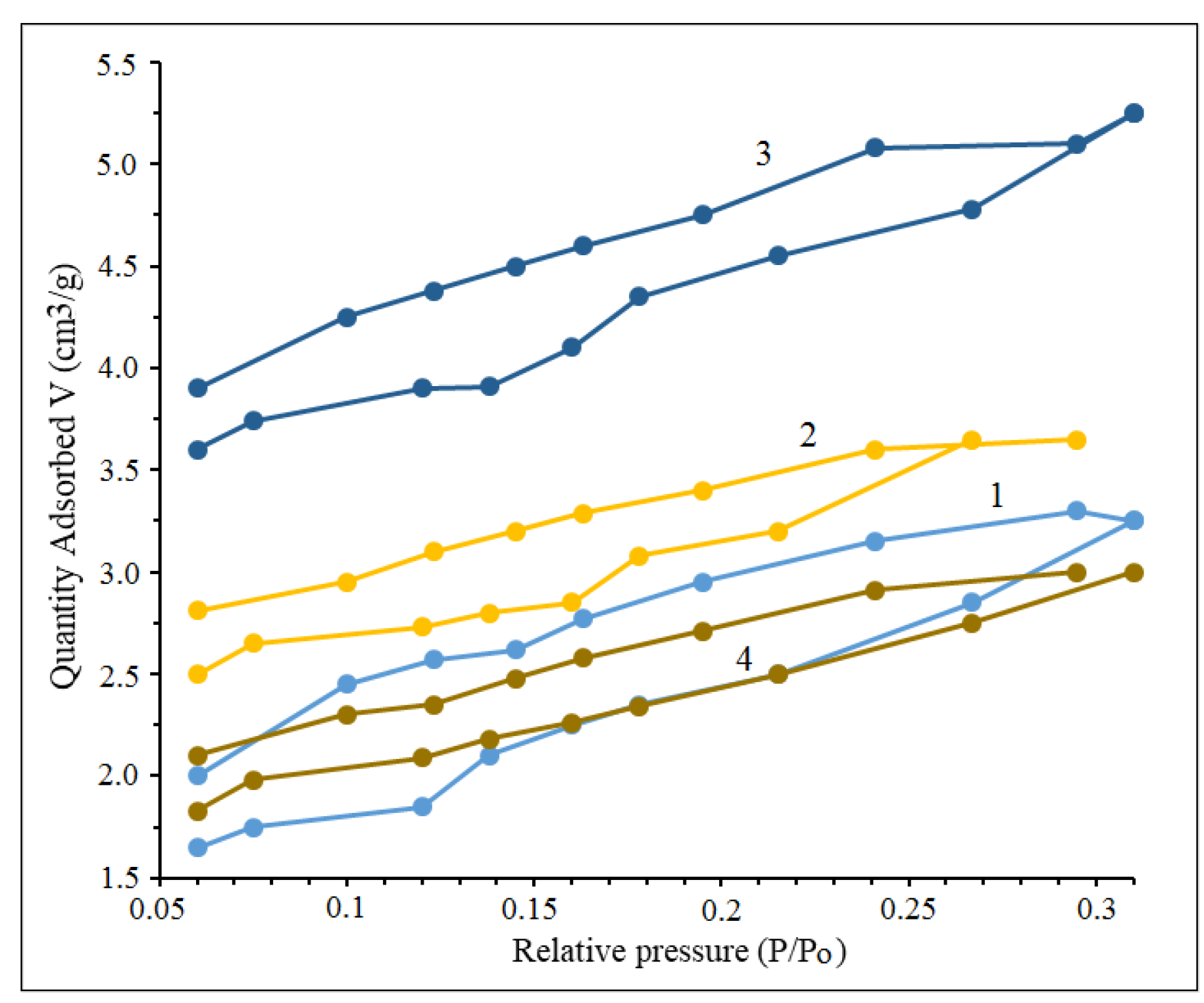

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of catalysts

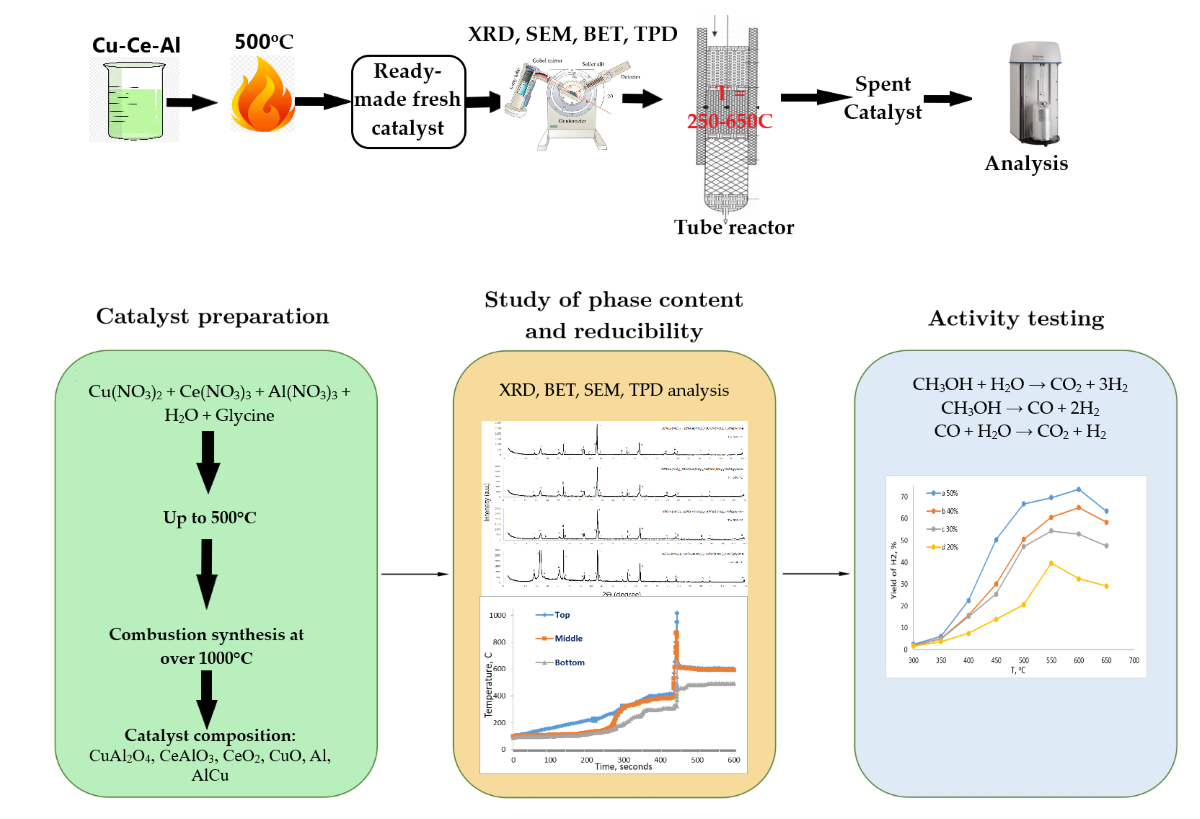

The study presents the results of catalysts based on the Cu-Ce-Al system, obtained through solution combustion synthesis method. Post-combustion, the catalysts were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) to identify and determine the phases. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis were employed to ascertain the composition and specific surface area of the catalysts. The following reactions are possible in the process of solution combustion synthesis (

Table 1).

The composition of the initial mixture, combustion conditions and the final catalyst compositions are shown in

Table 2.

2.1.1. XRD and BET analysis

The resulting catalysts had a similar qualitative composition, but different in the phase ratio. The approximate ratio between the phases was determined from the relative intensities of the X-ray diffraction peaks for each phase (

Figure 1).

In

Figure 1 which demonstrates the XRD diffraction patterns of the synthesized catalysts were shown that after preparation of catalyst by the solution combustion method Cu(NO

3)

2 species were identified as CuO, Al-Cu (intermetallic) and CuAl

2O

4 (spinels). As for aluminum nitrate, it mainly passed through an intermediate product in the form of aluminum oxide into cerium and copper spinels, as well as into intermetallites. Evident overlap between these diffraction peaks and other diffraction peaks points to a low concentration of Al

2O

3.

Research on methanol adsorption and decomposition on copper-based surfaces revealed that methanol undergoes dissociative adsorption, resulting in the formation of methoxy species (CH

3O) [

29]. It is assumed that absorbed O is the initiator of the formation of methoxy forms. Studies by some authors [

30] have shown that the O could be available from an incomplete reduction of the catalyst, such as the lattice oxygen of ceria, or from moisture that was present in the methanol feed.

The cerium species in prepared catalysts system of Cu(NO

3)

2 + Ce(NO

3)

3 + Al(NO

3)

3 + glycine in each options were recognized as cerium oxide (CeO

2) and spinel (CeAlO

3). As it is shown in the XRD patterns of catalysts the wide diffraction peaks of CuO indicates that cerium reduced crystalline size of Cu and increased the degree of dispersion, which is also mentioned in previous studies [

31].

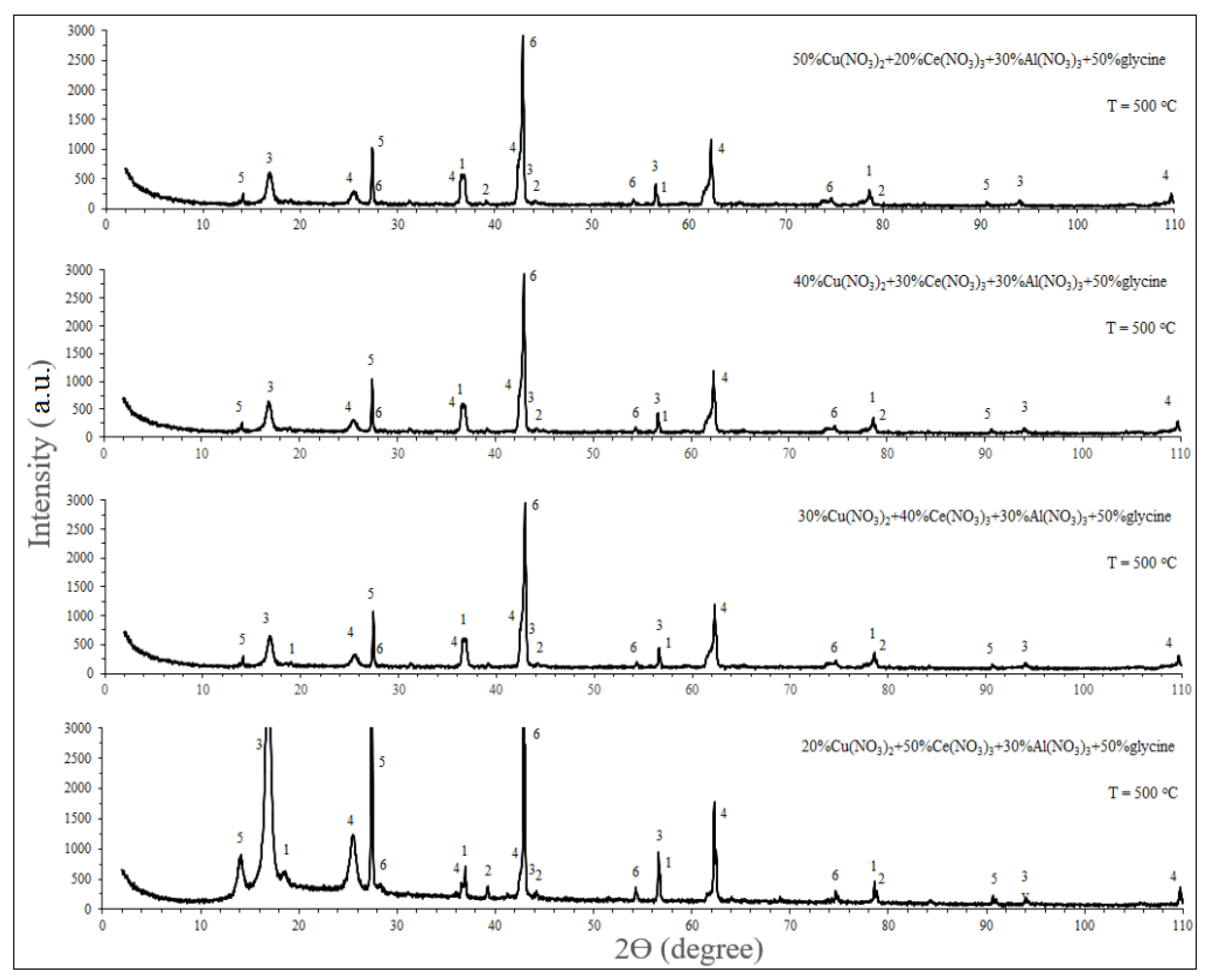

The temperature curves recorded during SCS exhibit a second peak following the SCS, as shown in

Figure 2. This can only be accounted for by the reaction between carbon and metal oxides. In this case the reaction Al

2O

3 + C → Al + СО

2 may give an explanation for presence of Al in the product of reaction, because hydrogen, which appears during reaction can’t reduce Al

2O

3 under conditions of synthesis. This has already been found in early studies [

32].

The catalysts of this series were prepared in a muffle furnace heated to 500 oC. Temperatures were measured by 3 different thermocouples, which were placed in a glass with a solution of nitrates and glycine. During the synthesis process, two combustion modes were carried out: volumetric explosion and self-propagating mode. In the volume of the explosive mode, the solution is heated and the water evaporates. After the water evaporates, a gel forms. The temperature in the furnace gradually increases to a critical point, and then the exothermic reaction occurs throughout the entire volume of the catalyst.

As shown in

Figure 2, during the synthesis of the catalyst, the solution evaporates when it reaches T = 100

oC, and when it reaches 172

oC, a gel is formed. The maximum temperature peak reaches at 445 seconds and the main synthesis reactions take place in this zone.

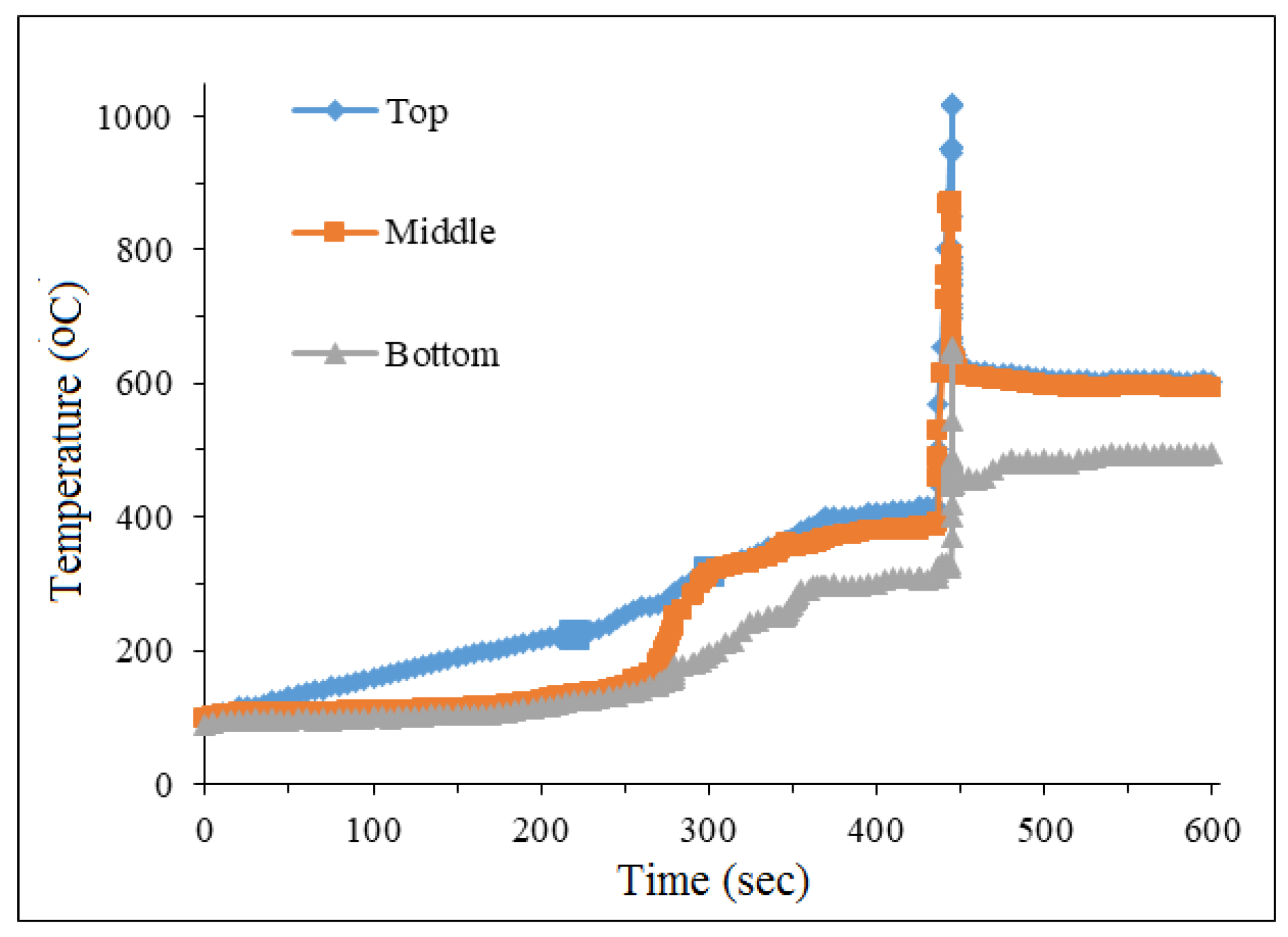

Unspent catalysts were examined by the BET method and adsorption and desorption isotherms by nitrogen were plotted for those catalysts (

Figure 3). According to the IUPAC classification, all samples were identified and classified as type IV isotherms, suggesting the presence of mesoporous structures.

The synthetic catalysts all exhibited H

2 hysteresis rings, indicating that their pore sizes were broad and varied. These included different pore types such as "ink bottle" pores, tubular pores with uneven sizes, and tightly packed spherical particle gap pores [

33].

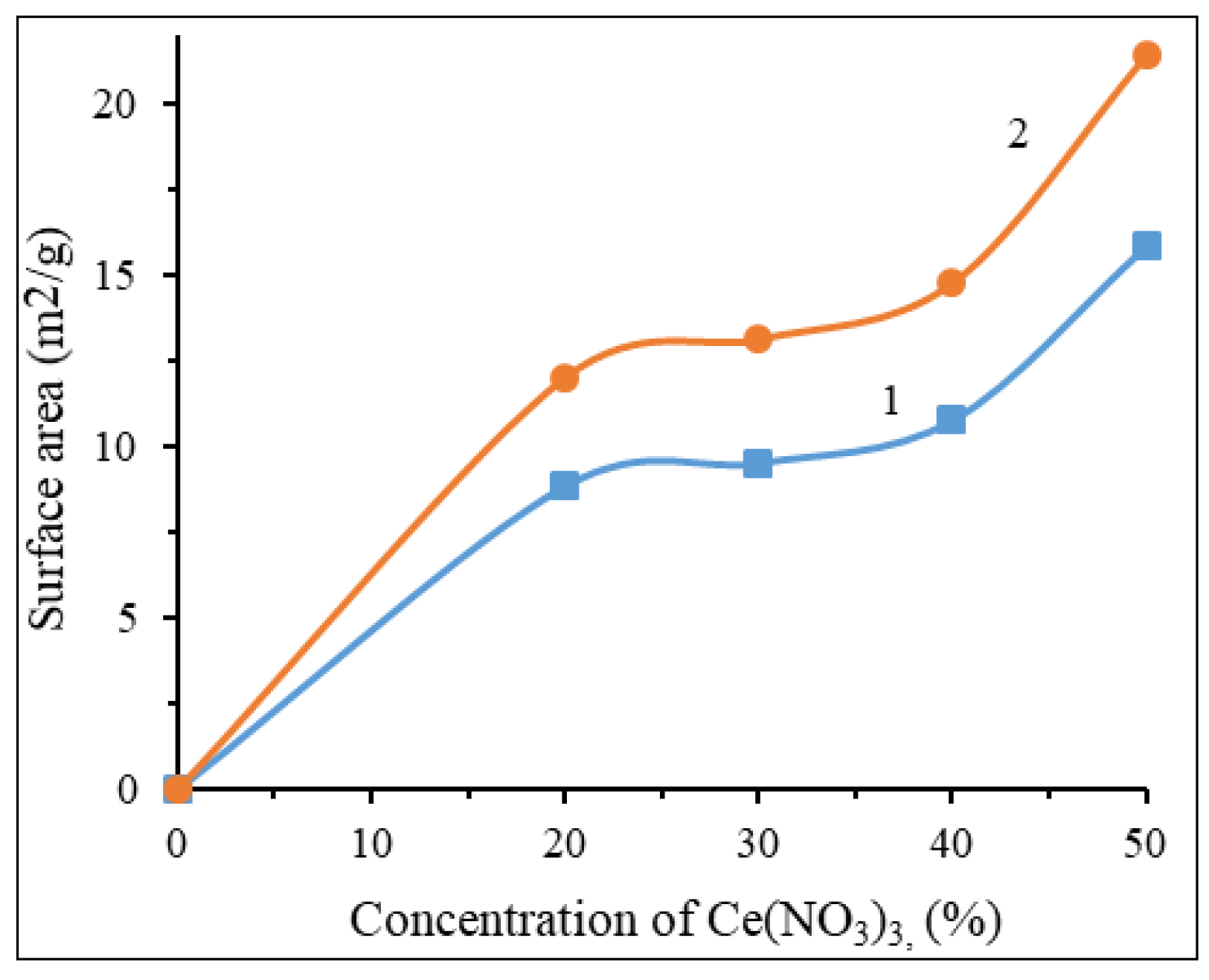

The surface area of all obtained catalysts was measured by the BET method. The areas are shown in the

Figure 4.

The concentration of cerium nitrate directly affects the surface area of these catalysts. As can be seen from the

Figure 4, an increase in Ce(NO

3)

3 content leads to an increase in surface area, which further affects the activity of the catalyst. As it is clear, 20% Cu(ΝO

3)

2 + 50% Ce(NO

3)

3 + 30% Al(NO

3)

3 + 50% glycine catalyst had the largest specific surface area between them. It should be noted that the specific surface area of the catalysts in this system is relatively low. This is explained by the high combustion temperatures during the preparation of the catalyst. Despite this, the synthesized catalysts have high activity, which allows them to be on par with expensive catalysts.

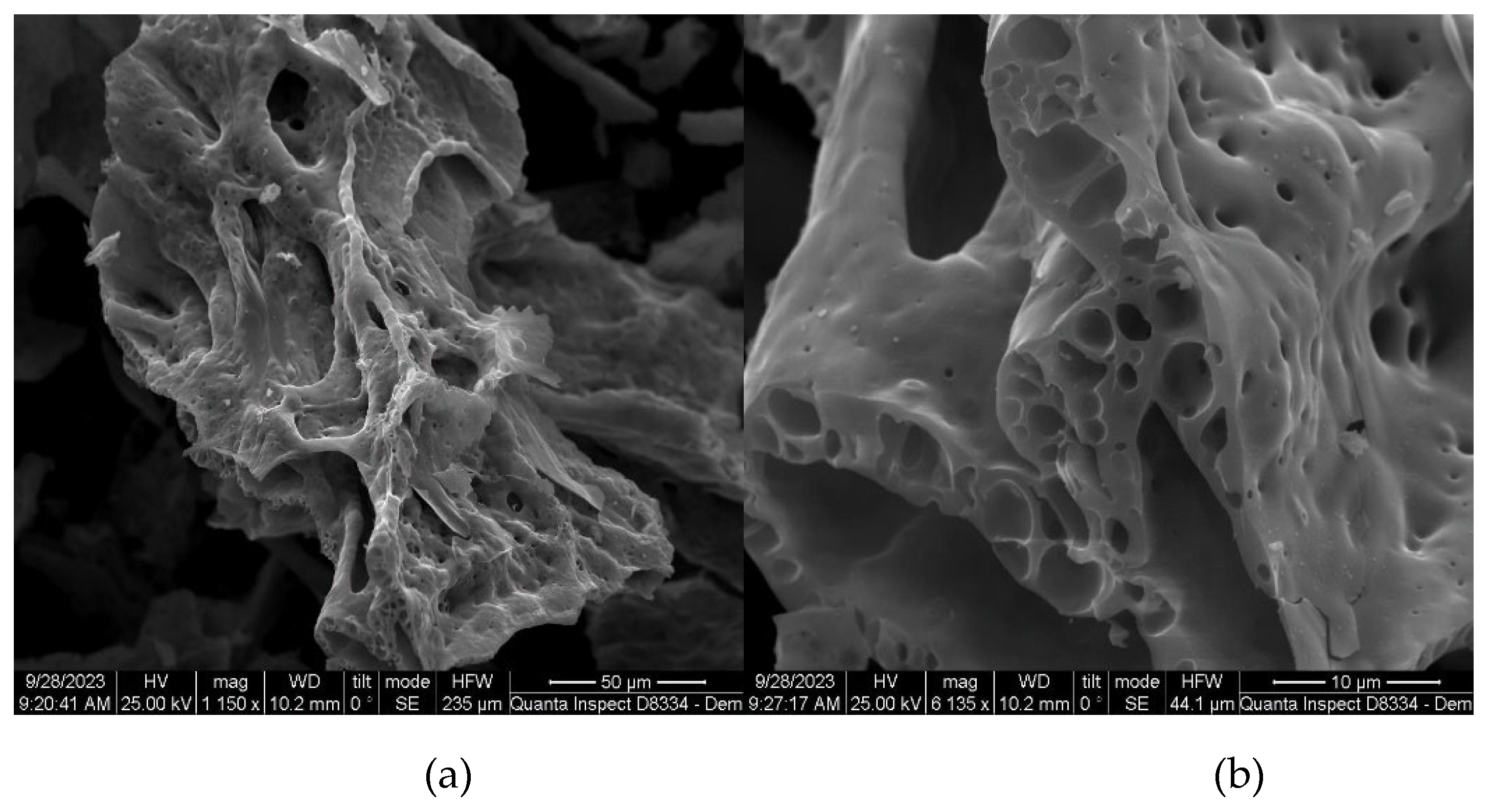

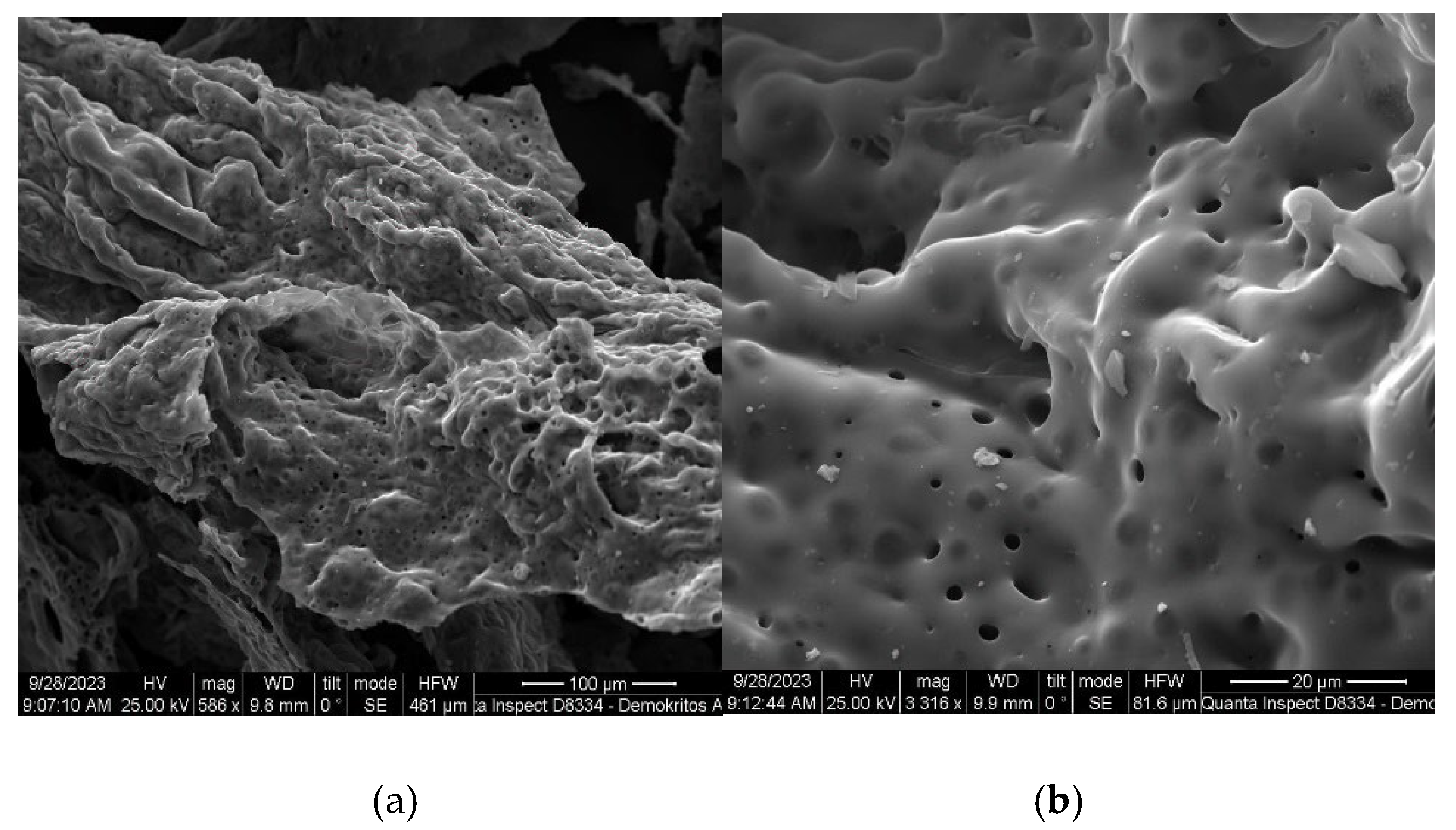

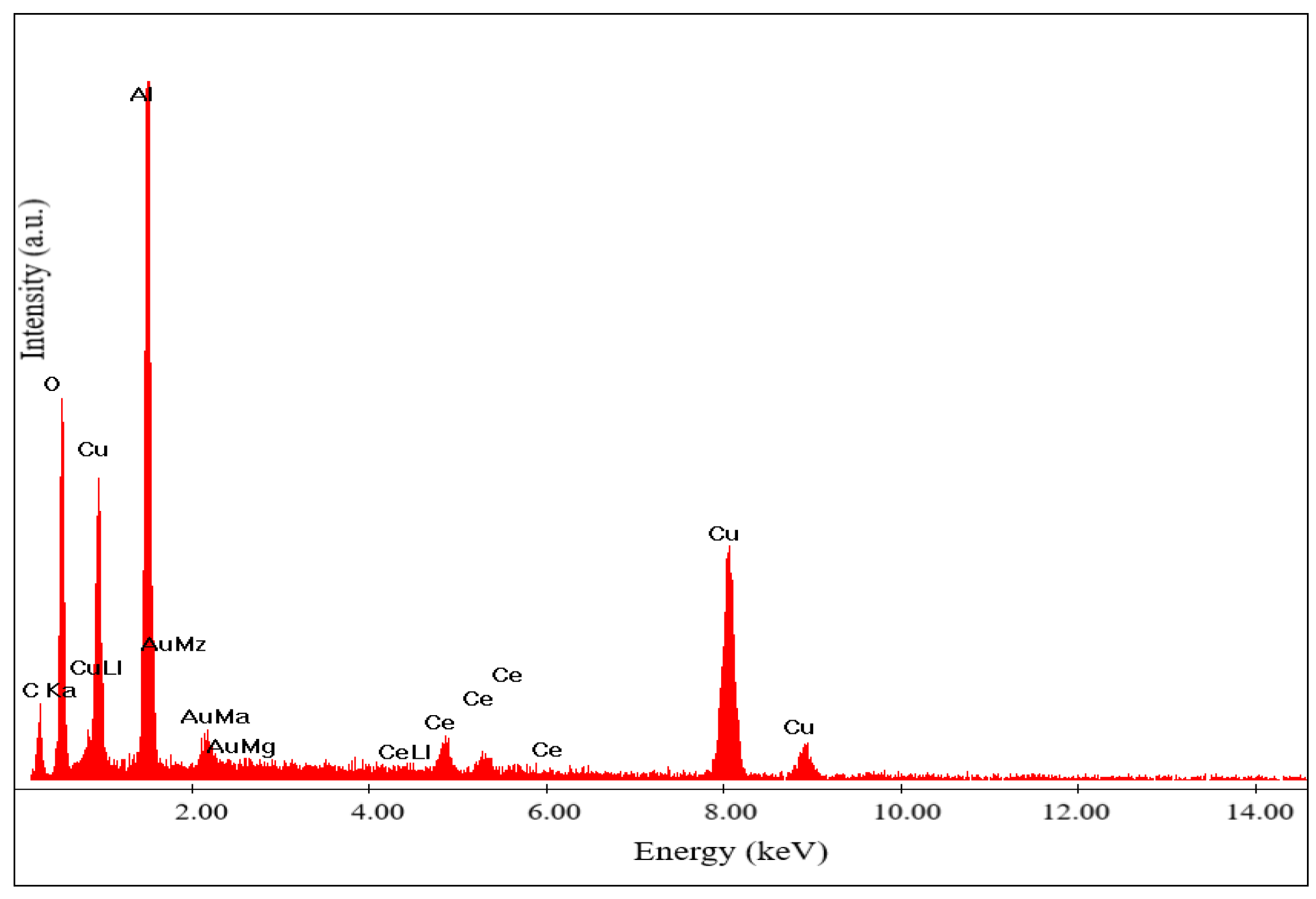

2.1.2. SEM analysis

The surface structure and morphology of the synthesized catalysts were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy. The results of SEM analyzes for catalysts containing 50% cerium nitrate and 20% copper nitrate are presented in the

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. Chemical analysis confirmed that the phase composition (CuAl

2O

4, Al, Al-Cu, CuO, CeO

2, CeAlO

3) aligns with the XRD data.

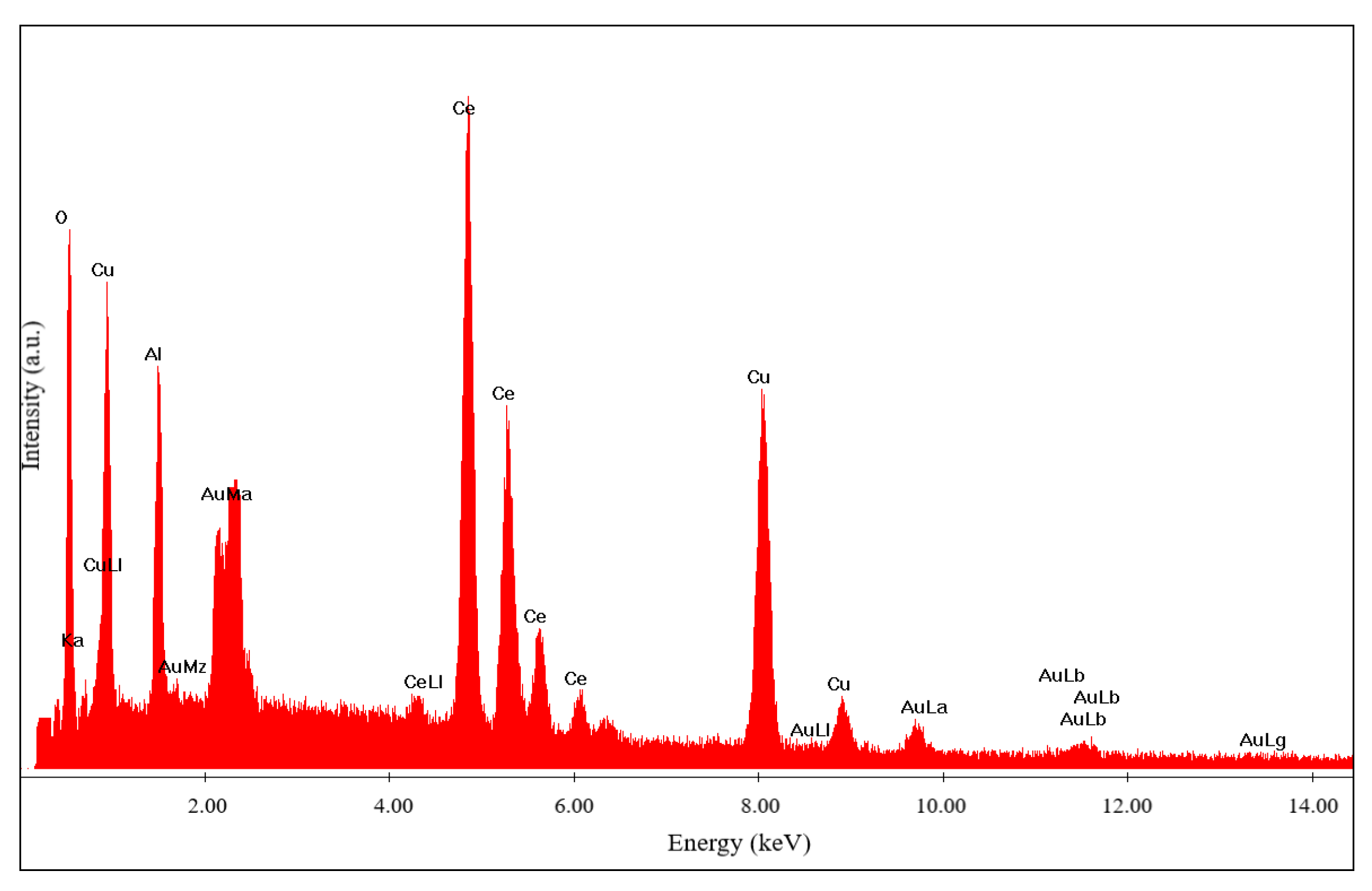

The contents of cerium, copper, aluminum and oxygen located and identified in different areas (

Figure 6). Very high content of these components match to the mentioned above spinel phases.

Chemical analysis (

Figure 8) was carried out for the catalyst shown in

Figure 7.

Thus, Cu(ΝO3)2-Ce(NO3)3-Al(NO3)3 catalysts with different element ratios were synthesized, and their combustion characteristics, composition, structure, and specific surface area and pores were analyzed.

2.2. Catalytic results

For determining of activity of synthesized series of catalysts were studied in the process of steam reforming of methanol at temperature range between 250-650

oC. According to the data [

34] the catalytic activity of the catalyst is directly affected by the methanol’s steam reforming temperature.

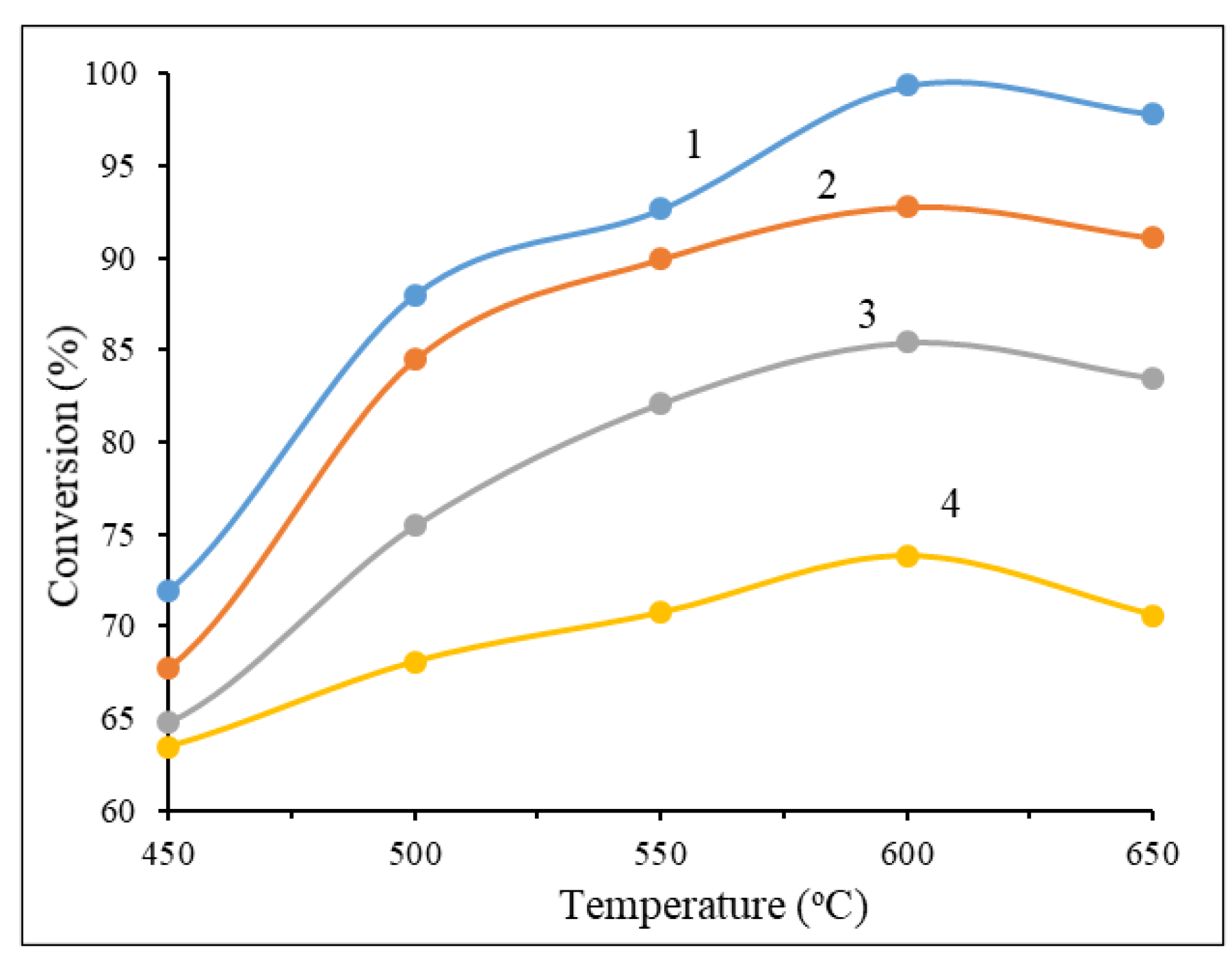

Figure 9 shows the results of these catalyst series activity on the conversion of methanol depending on the process temperature.

As its demonstrated in

Figure 9 the highest CH

3OH conversion (99.3%) is observed on a catalyst containing 20% Cu(NO

3)

2 + 20% Ce(NO

3)

3 + 30% Al(NO

3)

3 at the 600 °C temperature and then it starts to falling down. Actually, the good results shown between 500-650 °C for all samples, but the amount of the cerium nitrate plays a big role in this system of catalysts. Decreasing the content of Ce(NO

3)

3 naturally leads to a decrease in catalyst activity, which confirms the previously discussed results of BET analyzes. The results of studies of the influence of temperature and component content of catalysts on the yield of the target product are shown in

Figure 10.

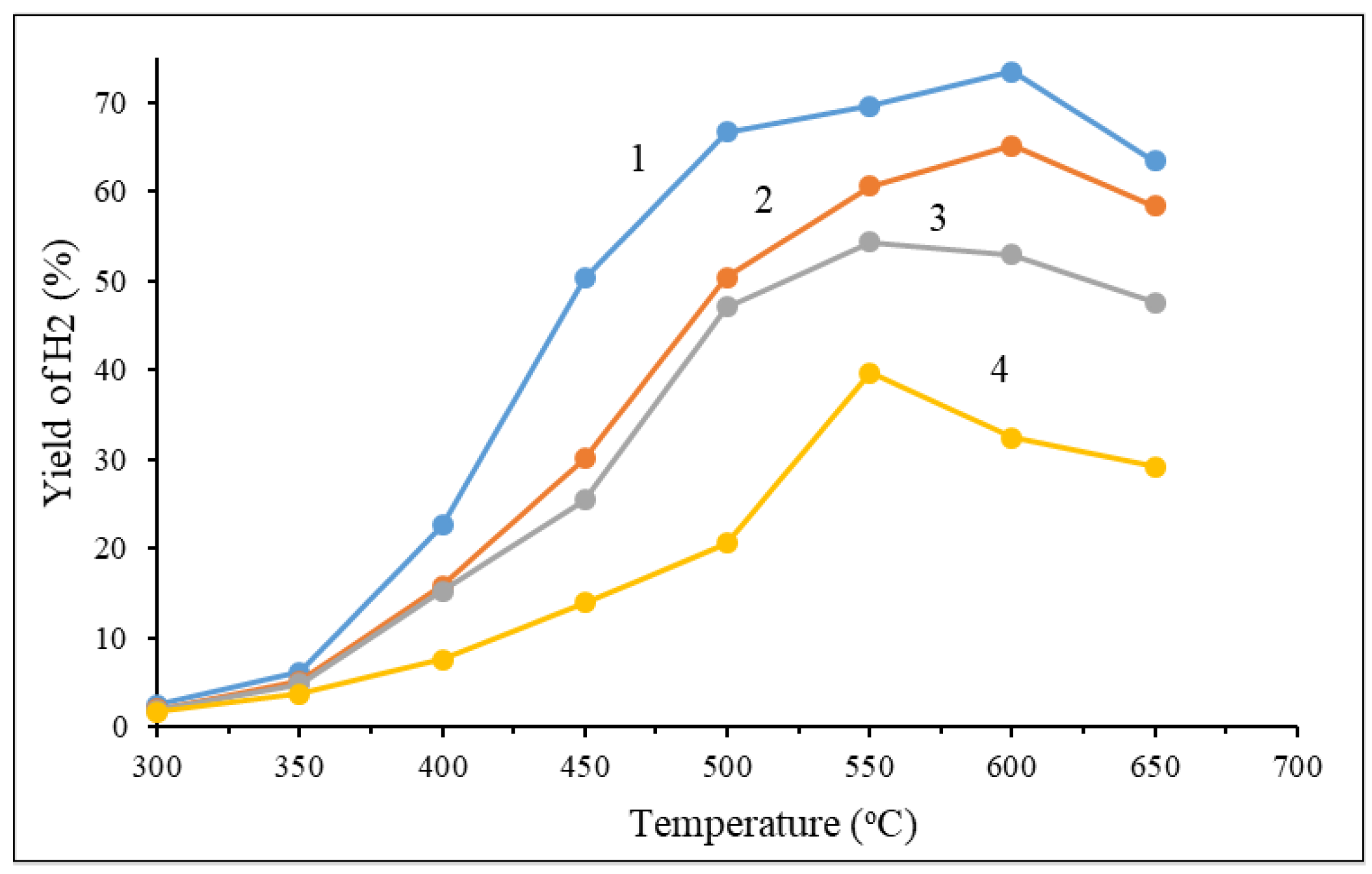

As disgplayed in

Figure 10, the hydrogen yield of the four catalysts showed a trend of first increasing and then reducing (600 °C) with the increase in temperature. 50% Cu(ΝO

3)

2 + 20% Ce(NO

3)

3 + 30% Al(NO

3)

3 + 50% glycine has a larger difference with the change of temperature. This may be due to the sintering of the active components of Cu at high temperature, which caused the reducing of hydrogen yield. In this case, also the content of Ce shows the same effect as in the conversion of methanol. The sample, which has 50% of cerium nitrate, had a higher catalytic activity than the 20% sample it might be explained by the dispersion of Cu was improved by increasing the content of cerium. The yield of carbon oxide is shown in

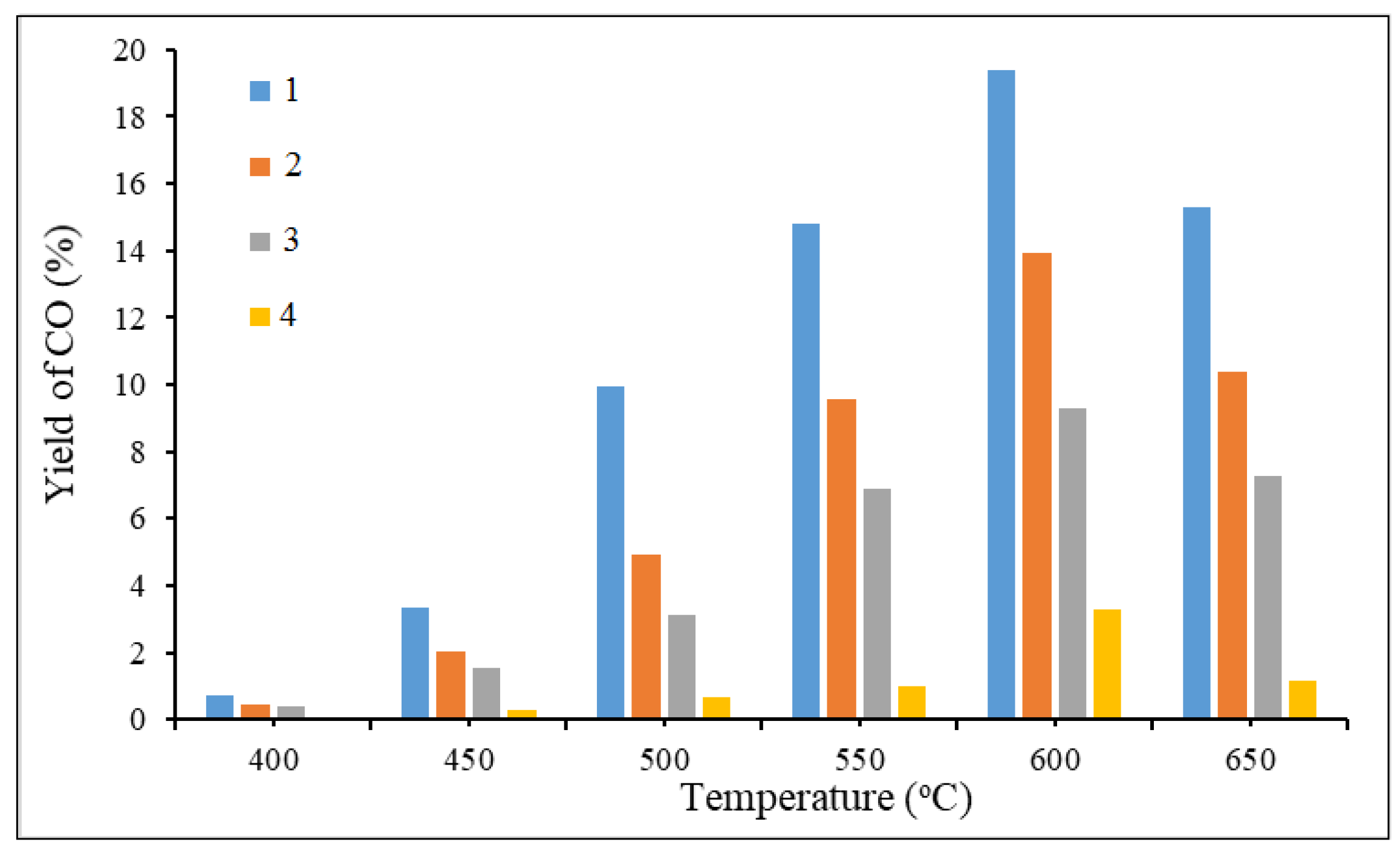

Figure 11.

From the

Figure 11, it can be seen that an increase in temperature promotes carbon oxide generation. Also, it can be recognized that an increase in the concentration of cerium nitrate in the composition of the initial catalyst unexpectedly leads to a decrease in the ratio of hydrogen to carbon monoxide (H

2/CO) in this series of catalysts for almost three times. It is because of cerium may suppress the methanol decomposition and reverse water gas shift reactions eventually end-up with the low CO and hydrogen rich product stream.

Based on the results of the above-described analyses, the most active catalyst (20% Cu(ΝO

3)

2 + 50% Ce(NO

3)

3 + 30% Al(NO

3)

3 + 50% glycine sample) among those synthesized by the SCS method was identified, and additional analysis was carried out for it in the form of temperature programmed desorption of oxygen. Results of it is shown in the

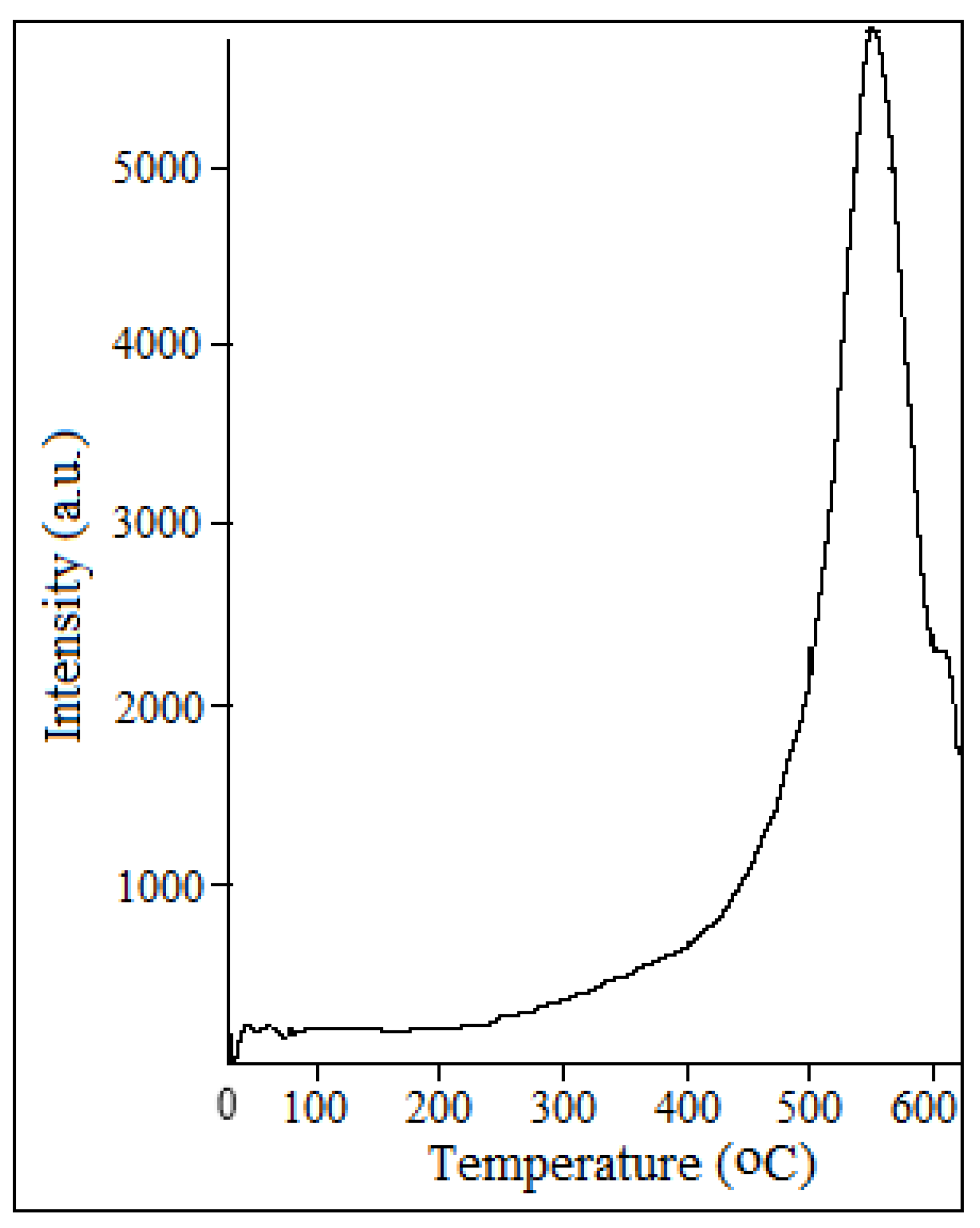

Figure 12.

The high intensity (over 5000) of oxygen desorption were noticed at 550-570 °C, but in spent catalyst sample the intensity decreased. The total amount of released oxygen monotonously changes in this heat treatment temperature range.

The catalysts maintained a constant weight following the catalytic studies, indicating no coke formation. The stability of the catalysts was tested over a span of 70 hours. During this period, the conversion rates of CH3OH exhibited minor fluctuations. Further, more comprehensive investigations into coke formation are currently being conducted.

The best SCS catalyst was evaluated against samples of identical composition that were prepared using the impregnation and self-propagating high temperature methods. The steam reforming of methanol was carried out in the reaction mixture of it with H

2O in ratio 2.5 : 1 respectively under Ar flow with 50 ml/min rate.

Table 3 presents the results of the study.

Methanol conversion values are the best on the SCS catalysts, then and for samples prepared by SHS and the impregnation methods, respectively. The H2 selectivity is higher also for SCS catalysts and is at 88%, compared to 63–74% for the other catalysts. The largest surface (Langmuir) area had a catalyst synthesized by impregnation method and its over 100 m2/g and the next is SCS catalyst with almost 26 m2/g then SHS sample with 18 m2/g. Therefore, new composite materials produced through the SCS method possess a notable advantage. The generated hydrogen and CO mixture is pure and does not need further purification.

3. Materials and Methods

Catalysts based on Cu, Ce and Al were prepared by solution combustion synthesis method. For the preparation of catalysts, pre-calculated amounts of nitrate salts were used: Cu(NO3)2 × 6H2O (98-99% Sigma, Aldrich), Ce(NO3)3 × 6H2O (98-99% Sigma, Aldrich), Al(NO3)3 × 9H2O (98-99% Sigma, Aldrich), and glycine (98%, Oxford lab fine Chem LLP). These salts are pre-ground in an agate mortar and then mixed in a porcelain cup. Thereafter 10 mL of distilled water was gradually added to this mixture of salts, the resulting mixture was stirred in air for several minutes until complete dissolution. The muffle furnace was preheated to the required temperature (up to 500 °C). The prepared mixture was transferred from a porcelain cup to a heat-resistant glass beaker with a volume of 200 mL and placed in a heated muffle furnace. After 2-3 minutes, when the muffle furnace door was not fully opened, it was visually possible to observe combustion in the solution, in which this mixture rised over the walls of the glass when boiling. Urea was added to the composition of SCS catalysts to improve the combustion process. The presence of urea in the catalyst promoted a change of the solution into brown color during combustion. The beaker is then cooled in air and the prepared catalyst was placed in a glass jug.

The second series of catalysts was prepared by the incipient wetness impregnation. Analytically pure copper nitrate hexahydrate Cu(NO3)2 × 6H2O (98-99% Sigma, Aldrich), cerium nitrate hexahydrate Ce(NO3)3 × 6H2O (98-99% Sigma, Aldrich) were used for preparing the catalyst. The catalyst was prepared by using the equal amount impregnation method. Cu(NO3)2 × 6H2O and Ce(NO3)3 × 6H2O were weighed on an electronic balance, and a needed concentration of the metal element active component precursor solution was prepared, controlling the molar ratio of Ce : Cu. The pretreated activated alumina was placed in a conical flask, and the precursor solution was poured in until it was submerged in the activated alumina. The conical flask was shaken in a water bath shaker for 2 h, and the water bath temperature was set at 25 °C. The supporter was dried at 110 °C for 8 h. The catalyst was roasted in a muffle furnace at a controlled roasting temperature of 500 °C for 6 h.

SHS catalysts from the same material composition. Uniaxial pressing under a pres-sure of about 10 MPa was used to prepare cylindrical specimens that were 10 mm in diameter and 20 mm long. The initial reaction mixture was preliminarily heated in a muffle furnace at a temperature of 500-700 °C for 3–5 minutes before initiating the SHS reaction.

Temperature profiles were recorded during SCS in a muffle furnace preheated to 500 °C. Three thermocouples were positioned at the top of the muffle furnace, all placed within the glass. These thermocouples monitored the bottom, middle, and top layers of the solution. During the catalyst synthesis by solution combustion, two combustion modes were observed: a volumetric explosion and a self-propagating mode. In the volumetric explosion mode, the solution was heated and water evaporated. After the water evaporated, a gel formed. The temperature in the muffle furnace gradually rose to a critical point. Once this critical temperature was reached, an exothermic reaction occurred throughout the entire volume of the catalyst.

Atomic structure of the catalysts was determined by X-ray diffraction measurements on a Siemens Spellman DF3 spectrometer with Cu-Kα radiation. 10% KCl was added to samples as an internal standard to allow for a semi-quantitative XRD analysis. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area was carried out on a GAPP V-Sorb 2800 Analyser using nitrogen as a carrier gas. In the process of solution combustion synthesis, the nanopowders were obtained, and therefore the porosity for them was not measured. The microstructure of the materials was examined after spatter coating with gold (coating thickness 5–10 nm) by a scanning electron microscope (Quanta Inspect from FEI) together with point EDX elemental analysis.

Experiments on the steam reforming of methanol to hydrogen and carbon oxides were carried out on flow type installation at atmospheric pressure in a tubular quartz reactor with a fixed catalyst bed without any pre-reduction. Catalyst was placed in the central part of reactor and quartz wool placed above and below the catalyst bed. The catalytic reaction was carried out at temperature range between 250-650 °C using a mixture of CH3OH : H2O in the ratio of 2.5 : 1 as the feed. Such by-products were observed for majority of catalysts in very small amounts, indicating very high selectivity for H2.

The analysis of the initial mixture and reaction products was carried out using a chromatograph "Chromos GC-1000" with the "Chromos" software and on a chromatograph "Agilent Technologies 6890N" (USA) with the corresponding computer software. Chromatograph "Chromos GC-1000" is equipped with packed and capillary columns. The packed column was used for the analysis of Н2, О2, N2, СН4, С2Н6, С2Н4, С3-С4 hydrocarbons, СО and СО2, while the capillary column was used to analyze hydrocarbons. Temperature of the TC detector was 200 oС, the evaporator temperature 280 oС, column temperature 40 oС. Carrier gas Ar velocity was 10 mL/min. A HP-PLOT Q capillary column 30 m long and 0.53 mm in diameter filled with polystyrene-divinylbenzene was used for analysis on an "Agilent Technologies 6890N" chromatograph.

The chromatographic peaks were calculated from the calibration curves plotted for the respective products using the "Chromos" software for pure substances (accurately measured quantities of pure component or mixture of substances with known concentrations was injected into the chromatograph using a microsyringe). Based on the measured areas of the peaks corresponding to the amount of the introduced substance, a calibration curve V = f (S) was constructed, where V - amount of substance in ml, S - peak area in cm2. Concentrations of the obtained products were determined on the basis of the obtained calibration curves. The balance of regulatory substances and products was ± 3.0%.

4. Conclusions

The catalysts prepared by SCS method based on Cu(NO3)2-Ce(NO3)3-Al(NO3)3 systems in different ratio of components were investigated in steam reforming of methanol. The analysis of the catalysts using XRD, SEM, TPD and BET methods provided useful information in understanding the catalytic activity. Influence of the composition of initial components on formation of spinels, which were active in steam reforming of methanol was established. The best results showed the catalyst with 50% content of Ce(NO3)3 at T - 450-550 oС and P – 0.27 bar. Those conditions are very suitable for industry. There are advantages of SСS catalysts in comparison with the catalysts prepared by traditional impregnation and SHS methods in steam reforming of methanol. SCS is a rapid synthesis method, completing the catalyst production within minutes. It is cost-effective, utilizing exothermic reactions to create spinels at lower temperatures. The process allows for the synthesis of spinels by forming oxides from nitrates with a high defect structure, enabling reactions at significantly lower temperatures compared to oxides with well-formed crystal lattices. Due to the exothermic nature of SCS, temperatures exceed 1000 °C, resulting in a fast reaction rate and the formation of a defective crystal lattice, which is highly active in catalysis. These conditions are also ideal for adjusting the crystal lattice of spinels and enhancing the catalysts' activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.X. and S.T.; methodology, G.X.; validation, Y.A.; formal analysis, M.Zh. and Y.As.; investigation, Y.As.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.As.; writing—review and editing, Y.As.; supervision, S.T.; project administration, T.B.; funding acquisition, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number AP19677006.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are especially grateful to the staff of the laboratory of physical and chemical research methods.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mombekova, G.; Baimbetova, A.; Nurgabylov, M; Keneshbayev, B. The relationship between energy consumption, population and economic growth in developing countries. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J. Exnovating for a renewable energy transition. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, G.; Xie, M.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, G. A probabilistic analysis method based on Noisy-OR gate Bayesian network for hydrogen leakage of proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Reliab. Eng. & System Safety 2024, 243, 109862. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Li, G.; Ma, S.; Zhao, Z.; Li, N.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. Effect of hierarchical pore structure of oxygen carrier on the performance of biomass chemical looping hydrogen generation. Energy 2022, 3, 124301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, K,; Bae, S. ; Lee, J. Classification and technical target of water electrolysis for hydrogen production. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 95, 554–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G,; Wang, F. ; Li, L.; Zhang, G. Experiment of catalyst activity distribution effect on 8 methanol steam reforming performance in the packed bed plate-type reactor. Energy 2013, 51, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wu, Q.; Mei, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Development of pure hydrogen generation system based on methanol steam reforming and Pd membrane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 69, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tang, Y.; Ma, X.; Tang, J.; Yue, W. Biomass gasification based on sorption-enhanced hydrogen production coupled with carbon utilization to produce tunable syngas for methanol synthesis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 309, 118428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S.; Turner, J.; Sileghem, L.; Vancoillie, J. Methanol as a fuel for internal combustion engines. Prog. Energy Combust. 2019, 70, 43–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, C.; Yu, H.; Wu, H.; Jin, F.; Xiao, F.; Liao, Zh. Enhancement of methanol steam reforming in a tubular fixed-bed reactor with simultaneous heating inside and outside. Energy 2022, 254, 124330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, A.; Reyero, I.; Alfaro, C.; Bimbela, F.; Gandía, L.M. Syngas production by means of biogas catalytic partial oxidation and dry reforming using Rh-based catalysts. Catal. Today 2018, 299, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, M.; Onsan, Z.I.; Avci, A.K. Microchannelautothermal reforming of methane to synthesis gas. Top. Catal. 2013, 56, 1716–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tathod, A.P.; Hayek, N.; Shpasser, D.; Simakov, D.S.A.; Gazit, O.M. Mediating interaction strength between nickel and zirconia using a mixed oxide nanosheets interlayer for methane dry reforming. Appl. Catal., B 2019, 249, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touahra, F.; Chebout, R.; Lerari, D.; Halliche, D.; Bachari, K. Role of the nanoparticles of Cu-Co alloy derived from perovskite in dry reforming of methane. Energy 2019, 171, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, B.M.; Bulushev, D.A.; Beloshapkin, S.; Chansai, S.; Ross, J.R.H. Potassium-doped Ni-MgO-ZrO2catalysts for dry reforming of methane to synthesis gas. Top. Catal. 2013, 56, 1686–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkatova, L.A.; Pakhnutov, O.V.; Shmakov, A.N.; Naiborodenko, Y.S.; Kasatsky, N.G. Pt-implanted intermetallides as the catalysts for CH4-CO2 reforming. Catal. Today 2011, 171, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, G.; Thoda, O.; Roslyakov, S.; Steinman, A.; Kovalev, D.; Levashov, E.; Vekinis, G.; Sytschev, A.; Chroneos, A. Solution combustion synthesis of nano-catalysts with a hierarchical structure. J. Catal. 2018, 364, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manukyan, K.V.; Cross, A.; Roslyakov, S.; Rouvimov, S.; Rogachev, A.S.; Wolf, E.E.; Mukasyan, A.S. Solution combustion synthesis of nano-crystalline metallic materials: Mechanistic studies. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013, 117, 24417–24427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, A.; Roslyakov, S.; Manukyan, K.V.; Rouvimov, S.; Rogachev, A.S.; Kovalev, D.; Wolf, E.E.; Mukasyan, A.S. In situ preparation of highly stable Ni-based supported catalysts by solution combustion synthesis. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014, 118, 26191–26198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasyan, A.S.; Roslyakov, S.; Pauls, J.M.; Gallington, L.C.; Orlova, T.; Liu, X.; Dobrowolska, M.; Furdyna, J.K.; Manukyan, K.V. Nanoscale metastable ε-Fe3N ferromagnetic materials by self-sustained reactions. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 5583–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shteinberg, A.S.; Lin, Y.C.; Son, S.F.; Mukasyan, A.S. Kinetics of high temperature reaction in Ni-Al system: Influence of mechanical activation. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010, 114, 6111–6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, A.; Mukasyan, A.S.; Rogachev, A.S.; Manukyan, K.V. Solution combustion synthesis of nanoscale materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14493–14586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanasios, K.; Xanthopoulou, G.; Vekinis, G.; Zoumpoulakis, L. Co-Al-O catalysts produced by SHS method for CO<sub>2</sub> reforming of CH<sub>4</sub>. Int. J. Self-Prop. High-Temp. Synth 2014, 23, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, G. Some advanced applications of SHS: an overview. Int. J. Self-Prop. High-Temp. Synth. 2011, 20, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungatarova, S.A.; Xanthopoulou, G.; Karanasios, K.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; Zhumabek, M.; Kaumenova, G. New composite materials prepared by solution combustion synthesis for catalytic reforming of methane. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 61, 1921–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou, G.; Karanasios, K.; Tungatarova, S.; Baizhumanova, T.; Zhumabek, M.; Kaumenova, G.; Massalimova, B.; Shorayeva, K. Catalytic methane reforming into synthesis-gas over developed composite materials prepared by combustion synthesis. React. Kinet., Mech. Catal. 2019, 126, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deorsola, F.A.; Andreoli, S.; Armandi, M.; Bonelli, B.; Pirone, R. Unsupported nanostructured Mn oxides obtained by solution combustion synthesis: Textural and surface properties, and catalytic performance in NOx SCR at low temperature. Appl. Catal., A. 2016, 522, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Wang, C.; Ding, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z. Enhanced activity of MnxW0.05Ti0.95−xO2−δ for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with ammonia by self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Catal. Commun. 2015, 64, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russel Jr., J. N.; Gates, S.M.; Yates Jr., J.T. Reaction of methanol with Cu(111) and Cu(111)+O(ads). Surf. Sci. 1985, 163, 516–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.D.; Cheng, H.; Hsiao, T.C. In situ DRIFTS study on the methanol oxidation by lattice oxygen over Cu/ZnO catalyst. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2011, 342-343, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, С.; Weng, J.; Liao, M.; Luo, Q.; Luo, X.; Tian, Z.; Shu, R.; Chen, Y.; Du, Y. Configuration of coupling methanol steam reforming over Cu-based catalyst in a synthetic palladium membrane for one-step high purity hydrogen production. J. Energy Inst. 2023, 108, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumabek, M.; Xanthopoulou, G.; Tungatarova, S.A.; Baizhumanova, T.S.; Vekinis, G.; Murzin, D. Biogas Reforming over Al-Co Catalyst Prepared by Solution Combustion Synthesis Method. Catalysts 2021, 11(2), 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xi, H. Research progress of gas-solid adsorption isotherms. Ion Exchange and Adsorption 2004, 20, 376–384. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, M.V.; Fermoso, J.; Pevida, C.; Chen, D.; Rubiera, F. Production of fuel-cell grade H2 by sorption enhanced steam reforming of acetic acid as a model compound of biomass-derived bio-oil. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 184, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

X-ray spectra for the Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3 + Al(NO3)3 + glycine + H2O system at a preheating temperature of the initial mixture of 500 °C.

Figure 1.

X-ray spectra for the Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3 + Al(NO3)3 + glycine + H2O system at a preheating temperature of the initial mixture of 500 °C.

Figure 2.

Temperature curves during SCS of sample with initial batch 30% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 2.

Temperature curves during SCS of sample with initial batch 30% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 3.

N2 adsorption isotherm of synthesized catalysts: 1 - 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 2 - 40% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 3 - 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 4 - 30% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 3.

N2 adsorption isotherm of synthesized catalysts: 1 - 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 2 - 40% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 3 - 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 4 - 30% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 4.

The influence of the Ce(NO3)3 content in Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3 + Al(NO3)3 + glycine + H2O system on the surface area: 1 – multi-BET area, 2 – Langmuir area.

Figure 4.

The influence of the Ce(NO3)3 content in Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3 + Al(NO3)3 + glycine + H2O system on the surface area: 1 – multi-BET area, 2 – Langmuir area.

Figure 5.

SEM images of the catalyst with the initial composition of 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 at T = 500 oC with different magnification: (a) 1150, (b) 6135.

Figure 5.

SEM images of the catalyst with the initial composition of 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 at T = 500 oC with different magnification: (a) 1150, (b) 6135.

Figure 6.

Chemical analysis of the 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 catalyst.

Figure 6.

Chemical analysis of the 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 catalyst.

Figure 7.

SEM images of the catalyst with the initial composition of 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 at T = 500oC with different magnification: (a) 586, (b) 3316.

Figure 7.

SEM images of the catalyst with the initial composition of 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 at T = 500oC with different magnification: (a) 586, (b) 3316.

Figure 8.

Chemical analysis of the 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 catalyst.

Figure 8.

Chemical analysis of the 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 catalyst.

Figure 9.

Temperature dependence of methanol conversion for a series of catalysts: 1 - 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 2 - 30% Cu (ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 3 - 40% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 +50% glycine; 4 - 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 9.

Temperature dependence of methanol conversion for a series of catalysts: 1 - 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 2 - 30% Cu (ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 3 - 40% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 +50% glycine; 4 - 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 10.

Influence of temperature and component content of catalysts on H2 generation: 1 - 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 2 - 30% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 3 - 40% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 4 - 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 10.

Influence of temperature and component content of catalysts on H2 generation: 1 - 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 2 - 30% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 3 - 40% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 4 - 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 11.

Influence of temperature and component content of catalysts on CO yield: 1 - 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 2 - 30% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 3 - 40% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 4 - 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 11.

Influence of temperature and component content of catalysts on CO yield: 1 - 20% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 2 - 30% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 3 - 40% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine; 4 - 50% Cu(ΝO3)2 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% glycine.

Figure 12.

Intensity of oxygen desorption from the surface of catalyst depending on temperature.

Figure 12.

Intensity of oxygen desorption from the surface of catalyst depending on temperature.

Table 1.

Solution combustion reactions of the Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3 + Al(NO3)3 + H2O + urea system.

Table 1.

Solution combustion reactions of the Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3 + Al(NO3)3 + H2O + urea system.

| Reactions |

Remarks |

| 2Al(NO3)3 + 5C2H5NO2 + Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3 → Сu$$$+ CuO + CuxAly + CuCeOx + Ce2O3 + CuxAl2–xO3$$$+ CeAlO3 + 5CO2 + 8N2 + 10H2O |

500 °C. The total reaction of the SCS process |

| Al2O3 + C → Al + СО2, СuО + С → Сu + СО2

|

Carbon is formed by burning urea and reduces oxides to metal |

| Al + O2 → Al2O3

|

ΔНo278 = -3352 kJ/mol, exothermic reaction. The reduced metals can partially oxidize or react with another metal |

| Cu + O2 → CuO |

ΔНo278 = -475.8 kJ/mol, exothermic reaction |

| Al2O3 + CuO → CuAl2O4, Al2O3 + Ce2O3 → CeAlO3

|

Synthesis of spinel, endothermic reaction |

| Cu + Al → CuxAly

|

Synthesis of intermetallic compound |

Table 2.

The initial compositions of salts and final catalyst composition at 500 oC preheating temperature of solution.

Table 2.

The initial compositions of salts and final catalyst composition at 500 oC preheating temperature of solution.

| Starting compounds |

Catalysts composition |

| 50% Cu(NO3)2 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 20% Ce(NO3)3 + $$$50% glycine + 10 mL H2O |

CuAl2O4, CeAlO3, CeO2, CuO, Al, AlCu |

| 40% Cu(NO3)2 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 30% Ce(NO3)3 + $$$50% glycine + 10 mL H2O |

CuAl2O4, CeAlO3, CeO2, CuO, Al, AlCu |

| 30% Cu(NO3)2 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 40% Ce(NO3)3 + $$$50% glycine + 10 mL H2O |

CuAl2O4, CeAlO3, CeO2, CuO, Al, AlCu |

| 20% Cu(NO3)2 + 30% Al(NO3)3 + 50% Ce(NO3)3 + $$$50% glycine + 10 mL H2O |

CuAl2O4, CeAlO3, CeO2, CuO, Al, AlCu |

Table 3.

Comparison of Cu-Ce-Al catalysts prepared using the SCS, SHS and impregnation methods.

Table 3.

Comparison of Cu-Ce-Al catalysts prepared using the SCS, SHS and impregnation methods.

| Catalyst preparation method |

Conversion of CH3OH (%) |

Selectivity of H2 (%) |

Specific surface area (m2/g) |

| SCS |

99.3 |

88.8 |

25.8 |

| Impregnation |

75.6 |

74.7 |

102.9 |

| SHS |

83.8 |

63.2 |

18.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).