Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

04 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

3. Results

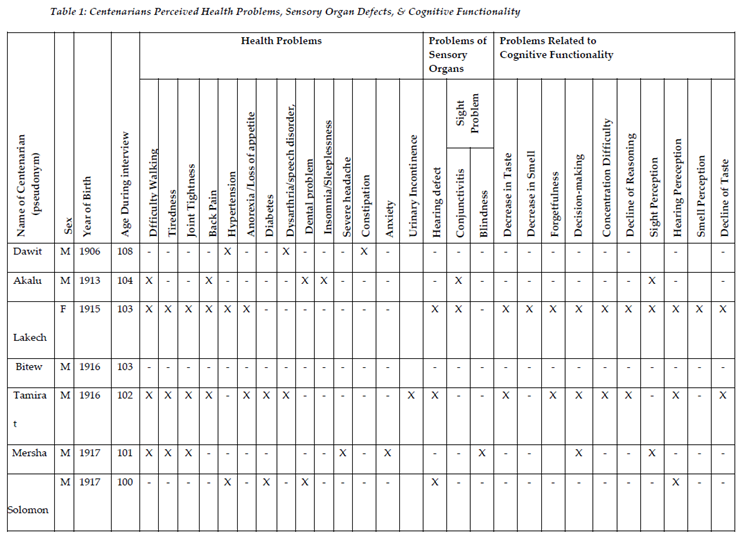

3.1. Description of Respondents

3.2. Perceived Health Problems

3.3. Decline of Sensory Functioning

3.4. Decline of Cognitive Functionality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cho, J., Martin, P., & Poon, L.W. The older they are, the less successful they become? Findings from the Georgia Centenarian Study. Journal of Aging Research, 2012, 695854. [CrossRef]

- Engberg, H., Christensen, K., Andersen-Ranberg, K., & Jeune, B. Cohort changes in cognitive function among Danish centenarians: A comparative study of 2 birth cohorts born in 1895 and 1905. Dementia & Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 2008, 26, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J. B., Poulain, M., Grinberg, D., Balcells, S., Busquets, X., Romaguera, D., Alonso-Fernandez, A., Busquets, X., Balcells, S., Gingberg, D. & Poulain, M. Description of extreme longevity in the Balearic Islands: Exploring a potential Blue Zone in Menorca, Spain. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 2014, 14(3), 620-627. [CrossRef]

- Stathakos, D., Pratsinis, H., Zachos, I., Vlahaki, I., Gianakopoulou, A., Zianni, D., & Kletsas, D. Greek centenarians: Assessment of functional health status and life-style characteristics. Experimental Gerontology, 2005, 40(6), 512–518. [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, G. Counting to 100: A first look at Cuba’s National Centenarian Study. MEDICC Review, 2009 11 (4), 1-19 https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/medicreview/mrw-2009/mrw094e.pdf.

- Serra, V., Watson, J., Sinclair, D. & Kneale, D. Living Beyond 100: A Report on Centenarians. London: International Longevity Centre, 2011.

- Green, C. M. Longevity Blue Zone Centenarians: An expository paper. Inquiries Journal, 2021, 13(05). http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1899.

- Freeman, S., Garcia, J. & Marston, H.R. Centenarian self-perceptions of factors responsible for attainment of extended health and longevity. Educational Gerontology, 2013, 39(10), 717-728. [CrossRef]

- Sadana, R., Foebel, A. D., Williams, A.N., & Beard, J. R. Population aging, longevity, and the diverse contexts of the oldest old. Public Policy & Aging Report, 2013, 23(20), 18-25. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Population ageing and development 2009. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations., 2009.

- Robine, J.M. & Cubaynes, S. Worldwide demography of centenarians. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 2017, 165 (Part B), 59-67. [CrossRef]

- Tanprasertsuk, J., Johnson, E.J., Johnson, M.A., Poon, L.W., Nelson, P.T., Davey, A., Martin, P., Barbey, A.K., Barger, K., Wang, X-D., & Scott, T.M. Clinico-neuropathological findings in the oldest old from the Georgia centenarian study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 70, 2019, 35–49. [CrossRef]

- Aboderin, I. Understanding and Responding to Ageing, Health, Poverty and Social Change in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Strategic Framework and Plan for Research. Outcomes of the Oxford Conference on Research on Ageing, Health and Poverty in Africa: Forging Directions for the Future. Oxford, 2005.

- Ferreira, M. & Kowal., P. Minimum Data Set on Ageing and Older Persons in Sub-Saharan Africa: Process and outcome. African Population Studies, 2013, 21 (1), 19-36. [CrossRef]

- 2021; 15. Author’s Own, 2021.

- Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. (CSA). The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia-Statistical Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2007.

- Jopp, D.S., Boerner, K., Cimarolli, V., Hicks, S., Mirpuri, S., Paggi, M., Cavanagh, A., & Kennedy, E. Challenges experienced at age 100: Findings from the Fordham Centenarian Study. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 2016, 28, 3, 187-207. [CrossRef]

- Richmond, R.L., Law, J., Kay-Lambkin, F. Morbidity profiles and lifetime health of Australian centenarians. Australian Journal on Ageing, 2012, 31(4), 227–232. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L., Teixeira, L., Ribeiro, O., & Paúl, C. Objective vs. subjective health in very advanced ages: Looking for discordance in centenarians. Front Medicine, 2018, 5 (189), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Haslam, A., Hausman, D.B., Davey, A., Cress, E.M., Johnson, M.A., & Poon, L.W. Associations between anemia and physical function in Georgia centenarians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2012, 60(12): 2362-2363. [CrossRef]

- Sebastião, E. Perceived poor health is positively associated with physical limitations and chronic diseases in Brazilian nonagenarians and centenarians. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 2015, 16, 1196–1203. [CrossRef]

- Selim, A.J., Fincke, G., Berlowitz, D.R., Miller, D.R., Qian, S.X., Lee, A., Cong, Z., Rogers, W., Selim, B.J., Ren, X.S., Spiro, A., & Kazis, L.E. Comprehensive health status assessment of centenarians: Results from the 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 2005, 60A(4), 515–519. [CrossRef]

- Takayama, M., Hirose, N., Arai, Y., Gondo, Y., Shimizu, K., Ebihara, Y., Yamamura, K., Nakazawa, S., Inagaki, H., Masui, Y., & Kitagawa, K. Morbidity of Tokyo-area centenarians and its relationship to functional status. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Science, 62A, 2007 (7), 774–782. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S., Kurosawa, H., Ebihara, S., & Kohzuki, M. Understanding the oldest old in northern Japan: An overview of the functional ability and characteristics of centenarians. Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 2010, 10 (1), 78-84. [CrossRef]

- Richmond, R.L., Law, J., & Kay-Lambkin, F. Physical, mental, and cognitive function in a convenience sample of centenarians in Australia. American Geriatrics Society, 2011, 59, 1080–1086. [CrossRef]

- Riberio, O., Duarte, N., Teixeira, L., & Paúl, C. Frailty and depression in centenarians. International Psychogeriatrics, 2018, 30, 1, 115–124. [CrossRef]

- Martin, P., Gondo, Y., Arai, Y., Ishioka, Y., Johnson, M.A., Miller, L.S., Woodard, J.L., Poon, L.W., & Hirose, N. Cardiovascular health and cognitive functioning among centenarians: A comparison between the Tokyo and Georgia centenarian studies. International Psychogeriatric, 2019, 31, 4, 455–465. [CrossRef]

- Evert, J., Lawler, E., Bogan, H., & Perls, T. Morbidity profiles of centenarians: Survivors, delayers, and escapers. Journals of Gerontology, 2003, 58, 3, M232-M237. [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, M., Darviri, C., Pelekasis, P., & Tigani, X. Demographic and anthropometric variables related to longevity: Results from a Greek centenarians’ study. Journal of Basic & Applied Sciences, 2015, 11, 381-388. [CrossRef]

- Duran-Badillo, T., Salazar-González, B.C., Cruz-Quevedo, J.E., Sánchez-Alejo, E.J., Gutierrez-Sanchez, G., & Hernández-Cortés, P.L. Sensory and cognitive functions, gait ability and functionality of older adults. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem, 2020; 28:e3282. [CrossRef]

- Herr, M., Arvieu, J.J., Robine, J.M., & Ankri, J. Health, frailty and disability after ninety: Results of an observational study in France: Health after ninety. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 2016, 66, 166-175. [CrossRef]

- Madrigal-Leer, F., Martìnez-Montandòn, A., Solìs-Umaña, M., Helo-Guzmàn, F., Alfaro-Salas, K., Barrientos-Calvo, I., Camacho-Mora, Z., Jimènez-Porras, V., Estrada-Montero, S., & Morales-Martìnez, F. Clinical., functional., mental and social profile of the Nicoya Peninsula centenarians, Costa Rica, 2017. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Italian Multicentric Study on Centenarians. Assessment of sense of taste in Italian centenarians. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 1998, 26(2), 177-183. [CrossRef]

- Kliegel, M., Moor, C., & Rott, C. Cognitive status and development in the oldest old: A longitudinal analysis from the Heidelberg Centenarian Study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 2004, 39, 143–156. [CrossRef]

- Jopp, D.S., Boerner, K., & Rott, C. Health and disease at age 100: Findings from the Second Heidelberg Centenarian Study. Deutsches Arzteblatt International, 2016, 113, 203–210. [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.H., Jilinskaia, E., & Perls, T.T. Cognitive functional status of age-confirmed centenarians in a population-based study. Journals of Gerontology, B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001, 56(3), 134-40. [CrossRef]

- Aladejare, S. A. Does external debt promote human longevity in developing countries? Evidence from West African countries. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 2023, 16, 213–237. [CrossRef]

- Perls, T. Successful aging and its subtypes in centenarians: The Chinese experience. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2023, 71 (5), 1362-1364. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. Sage. 2003.

- Saldana, J. Fundamentals of qualitative research. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2011.

- Yin, R. K. Case study research: Design and methods. (3rd Ed.) Sage, 2003.

- Dello Buono, M., Urciuoli, O., & De Leo, D. Quality of life and longevity: A study of centenarians. Age and Ageing, 1998, 27, 207-216. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Li, L., & Sun, J. Sensory impairment and all-cause mortality among the elderly adults in China: A population-based cohort study. Aging, 2020, 12(23), 24288-24300. [CrossRef]

- Toyoshima, A., Martin, P., Sato, S. & Poon, L.W. The relationship between vision impairment and well-being among centenarians: Findings from the Georgia Centenarian Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 2018, 33 (2), 414-422. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.K., Jones, R.N., Milberg, W.P., Tennstedt, S., Talbot, L., Morris, J.N., & Lipsitz, L.A. Effect of blood pressure and diabetes mellitus on cognitive and physical functions in older adults: A longitudinal analysis of the advanced cognitive training for independent and vital elderly cohort. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2005, 53(7), 1154-1161. [CrossRef]

- Cimarolli, V.R., & Jopp, D.S. Sensory impairments and their associations with functional disability in a sample of the oldest-old. Quality of Life Research, 2014, 23(7), 1977-1984. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J., Chang, P.S., Griffith, C.F., Hanley, S.I., & Lu, Y. The nexus of sensory loss, cognitive impairment, and functional decline in older adults: A scoping review. Gerontologist, 2021, 62 (8), 457-467. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L., Ribeiro, O., Teixeira, L., & Paúl, C. Predicting successful aging at one hundred years of age. Research on Aging, 2016, 38(6), 689-709. [CrossRef]

- McCormack, J. The emergence of centenarians and supercentenarians in Australia. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 2005, 4 (1), 178-179. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).