Submitted:

03 June 2024

Posted:

04 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- In the process of contribution measurement using Shapley, gradient multiplexing is performed: we use gradient approximation to reconstruct the model, which saves a lot of time. The reconfigurable model can be used to evaluate its performance more easily.

- Considering the heterogeneity of data distribution, a new aggregate weight is used to mitigate the impact of data heterogeneity on contribution measurement and improve the accuracy of contribution measurement.

- We propose a novel metric for measuring participant contributions in federated learning. By utilizing new aggregation weights, this method effectively mitigates the issue of data heterogeneity and enables a fairer assessment of participants’ contribution levels in the federated learning process.

2. Background

2.1. IID and Non-IID Data

2.2. Shapley Value

2.3. Federated Learning

3. Related Work

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Contribution Measurement Method based on Shapley Value

- Group Rationality: The value of the entire dataset is completely distributed among all users, i.e. .

- Fairness: (1) Two users who are identical with respect to what they contribute to a dataset’s utility should have the same value. That is, if user i and j are equivalent in the sense that: i.e., if , then i=j; (2) Users with zero marginal contributions to all subsets of the dataset receive zero payof: i.e., if , then i=0 for all .

- Additivity: The values under multiple utilities sum up to the value under a utility that is the sum of all these utilities: i.e., where are two utility tests.

4.2. Gradient-Based Model Reconstruction

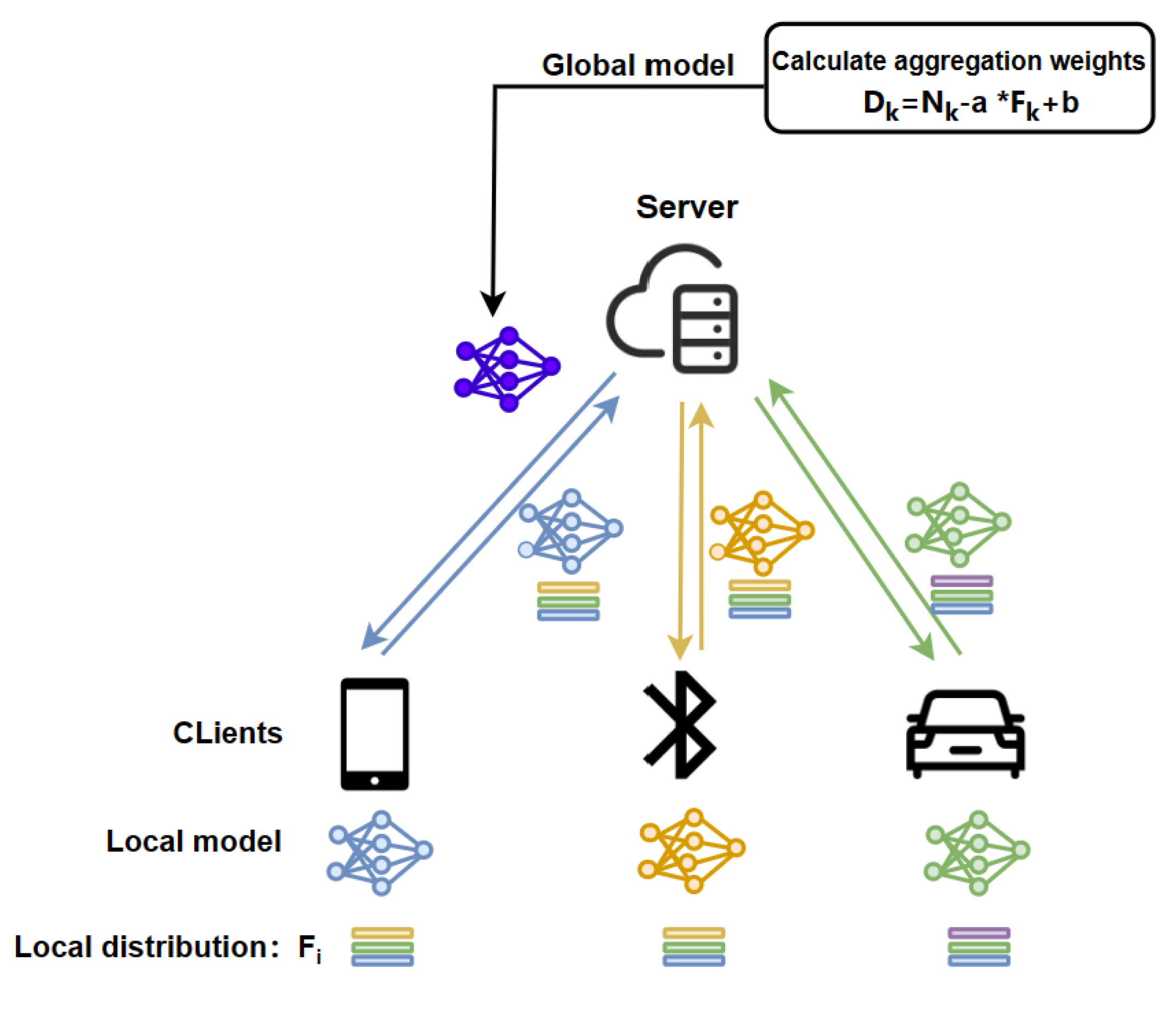

4.3. Build a new aggregate weight

4.4. New Aggregate Function

4.5. Contribution Measurement Algorithm based on Shapley Value

|

Algorithm 1: FL Participant Contribution Evaluation

|

|

Input: B is the local minibatch size, E is the number of local epochs, and is the learning rate, is the global distribution we set.

Server executes:

|

5. Experiment and Result

5.1. Dataset

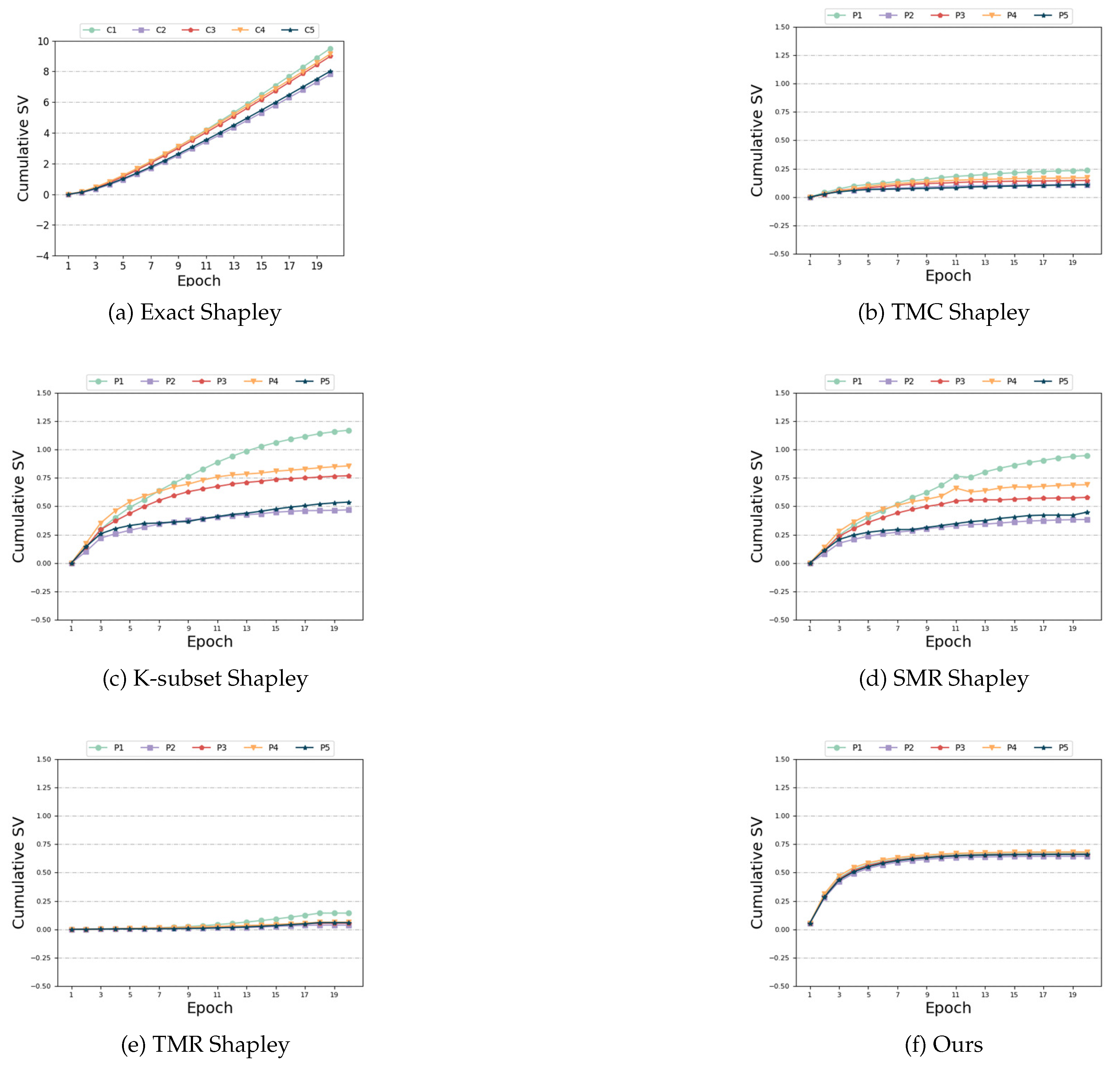

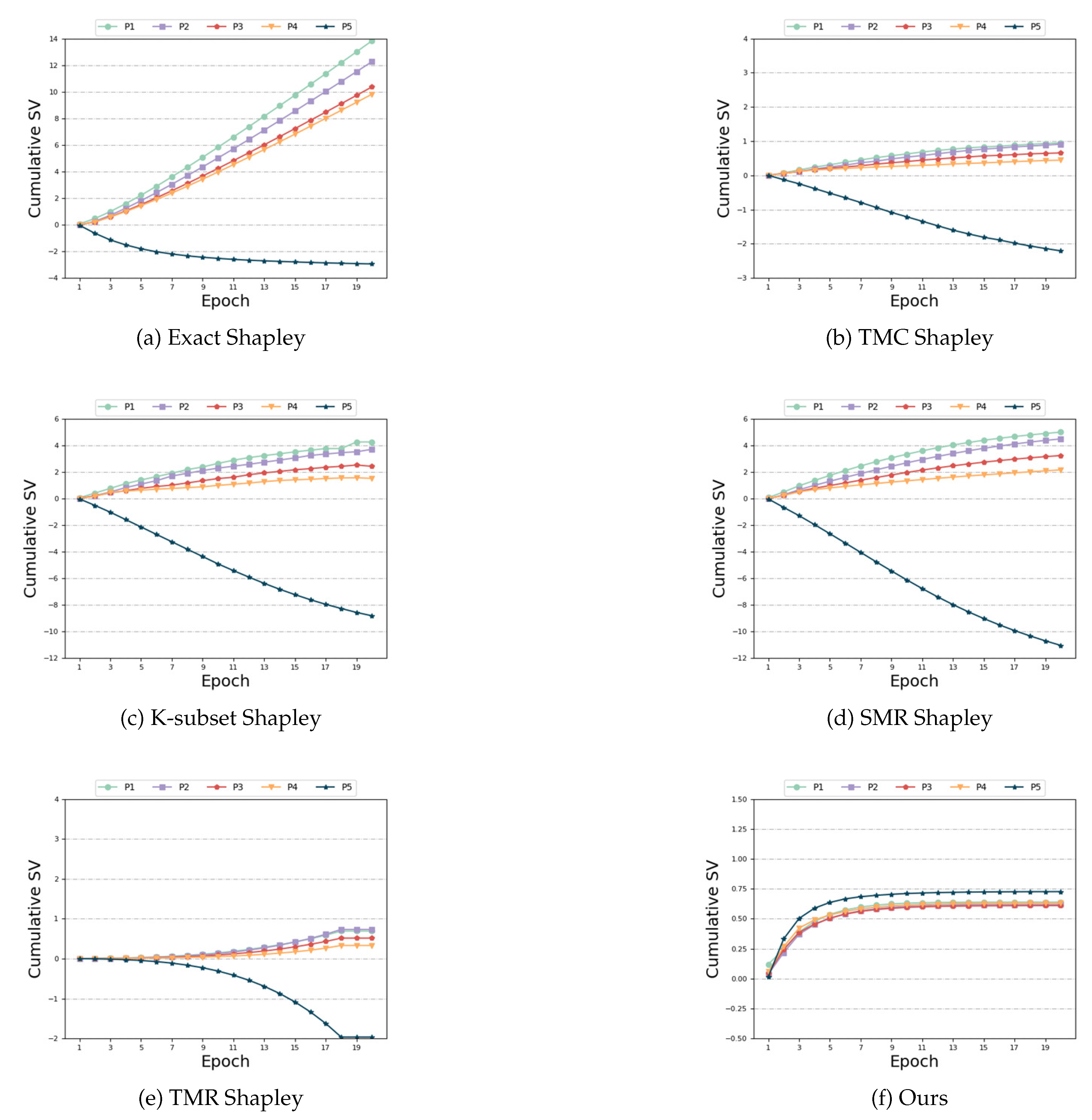

- Same Distribution and Same Size: In this setup, we randomly partitioned the dataset into five equally sized subsets, each containing the same number of images and maintaining the same label distribution.

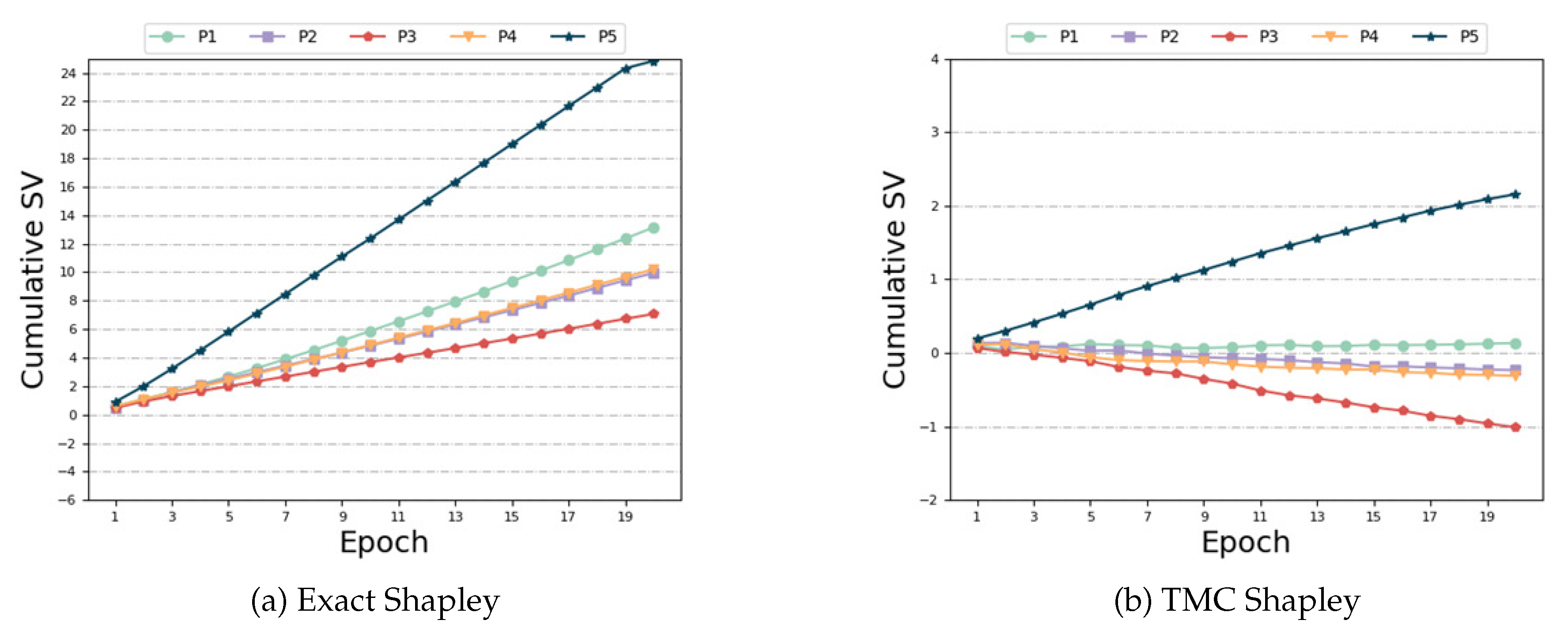

- Same Distribution and Different Size: We randomly sampled from the training set according to predetermined proportions to create a local dataset for each participant. We ensured that each participant has an equal number of images for each digit category. Participant 1 had a proportion of 2/20; Participant 2 had a proportion of 3/20; Participant 3 had a proportion of 4/20; Participant 4 had a proportion of 5/20; and Participant 5 had a proportion of 6/20.

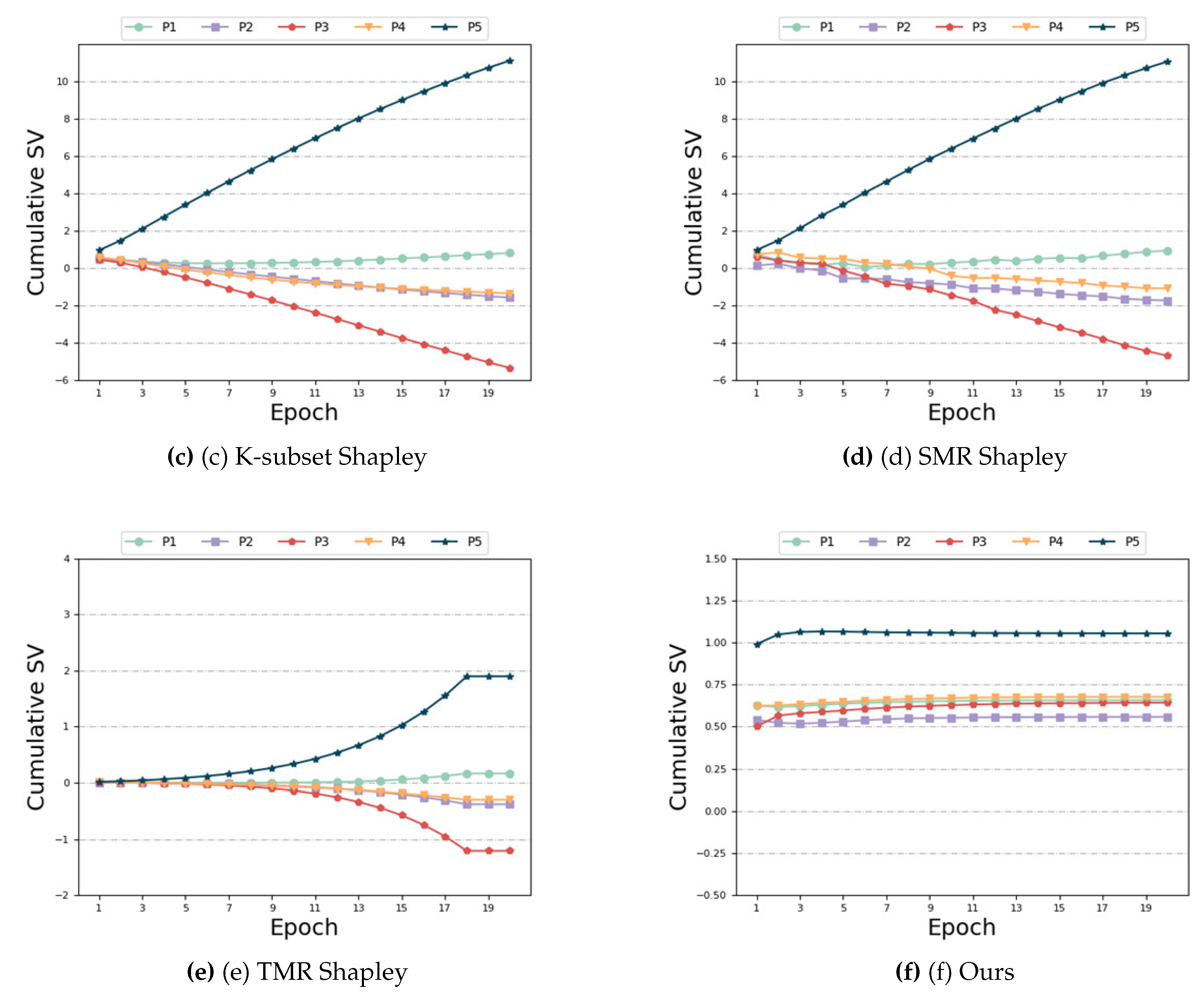

- Different Distributions and Same Size: In this setup, we divide the dataset into five equal parts, with each part having a distinct distribution of feature data. To be specific, the dataset for participant 1 comprises 80% of the samples labeled as ’1’ and ’2’, while the remaining 20% of the samples are equally distributed among the other numbers. This distribution strategy also applies to participants 2, 3, and 4. The final client exclusively contains handwritten numeric samples labeled as ’8’ and ’9’.

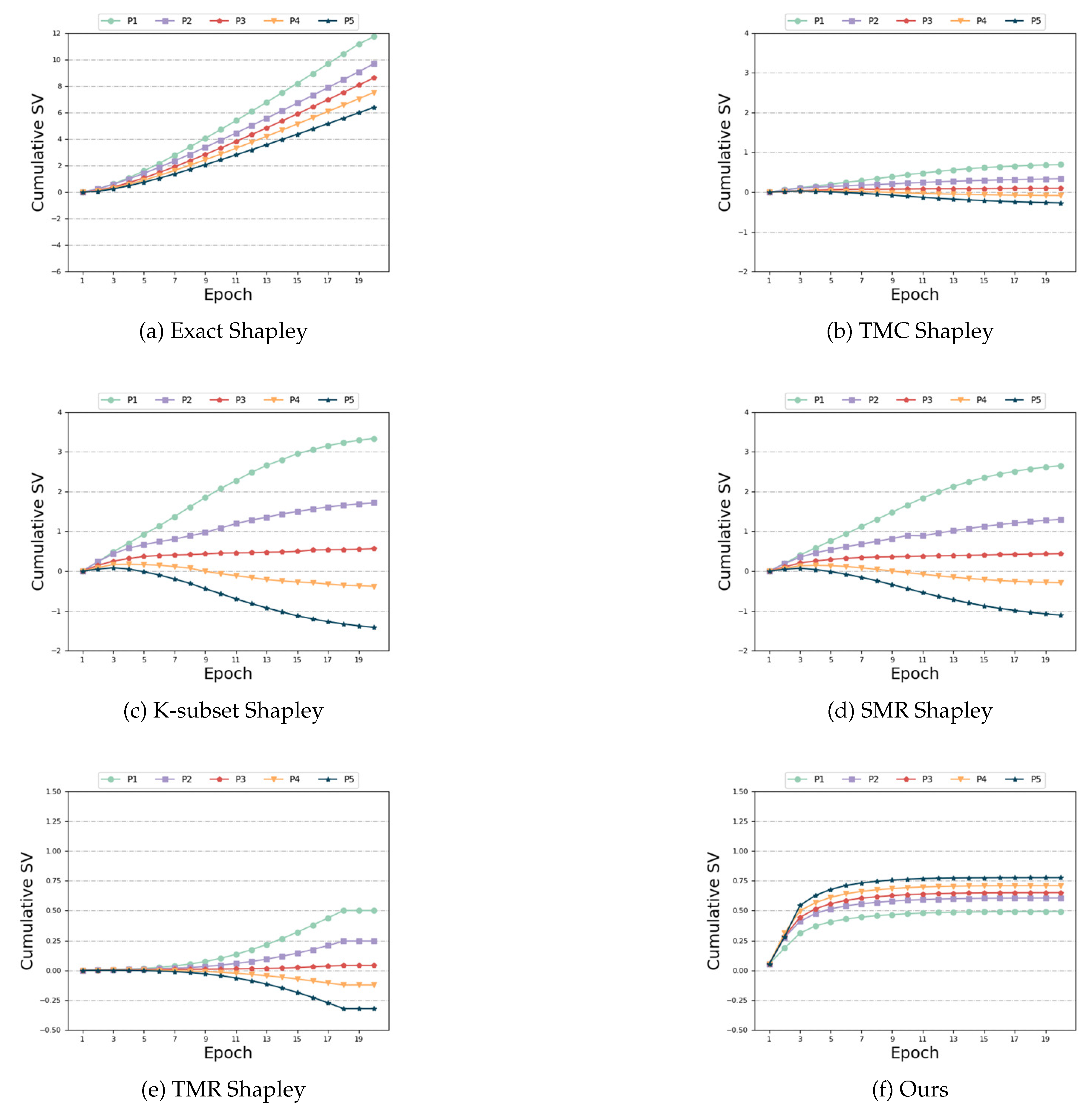

- Biased and unbiased: This method builds upon the ’Different Distributions and Same Size’ method by aiming to enhance the heterogeneity of data distributions among clients. Under the condition that each participant possesses an equal number of samples, the method employs a more heterogeneous setup. It includes four biased clients, each containing two categories of non-overlapping data, and one unbiased client with an equal number of samples from all ten categories.

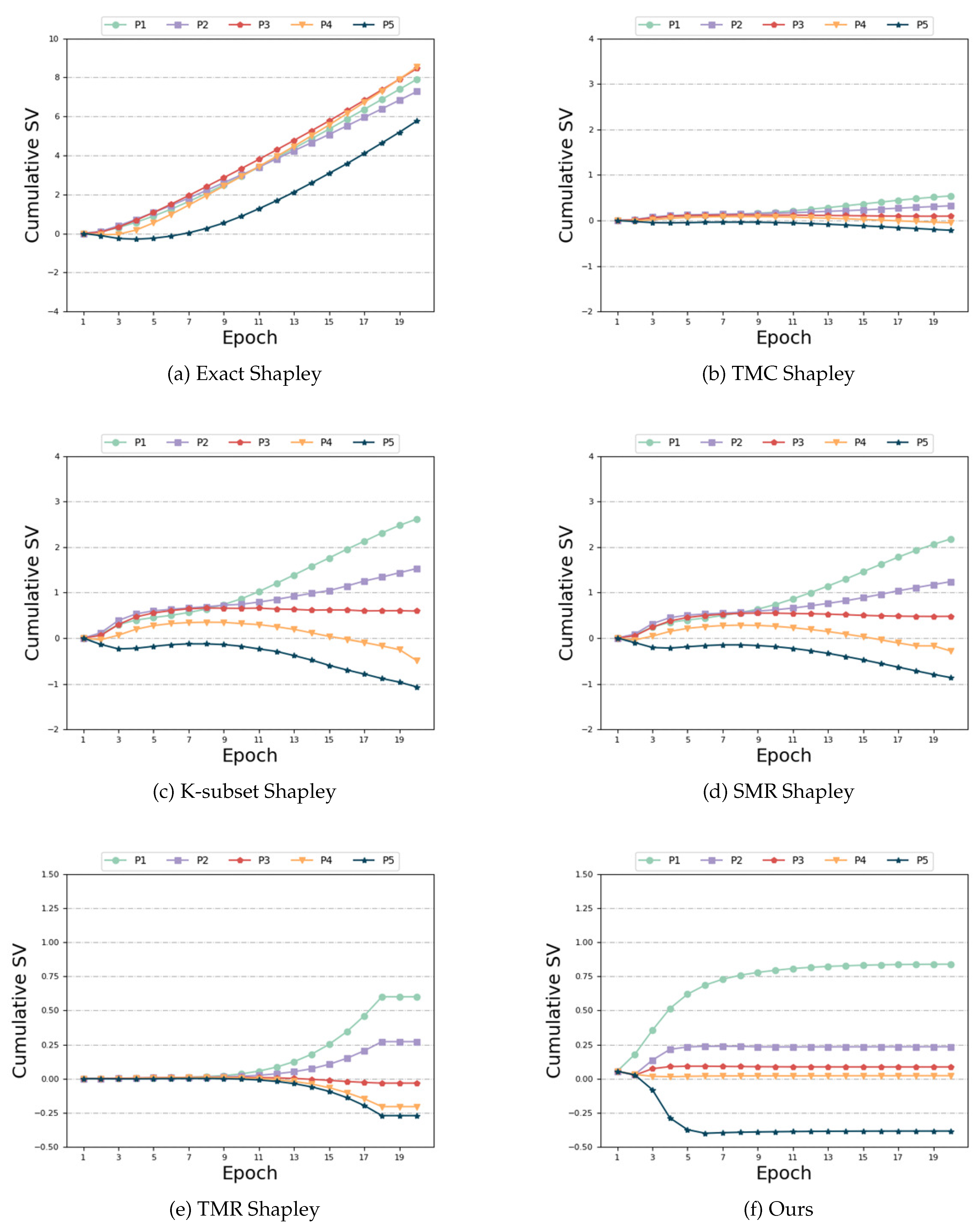

- Noisy Labels and Same Size: The data partitioning in this setting is identical to that in the ’Same Distribution and Same Size’ method. Subsequently, varying proportions of Gaussian noise are introduced to the input images. The specific configuration is as follows: participant 1 has 0% Gaussian noise ; participant 2 has 5% ; participants 3 have 10% ; participant 4 has 15% ; and participant 5 has 20%.

5.2. Baseline Algorithm

- Exact Shapley : This is the exact computation method proposed in literature[25]. This method calculates the original Shapley Values according to formula (3), which involves a large amount of sub-model reconstruction. It evaluates all possible combinations of participants, and each submodel is trained using their respective datasets.

- TMC Shapley: In this approach [25], models of a subset of FL participants are trained using their local datasets and the initial FL model. Mont-carlo’s Shapley Value estimation is performed by randomly sampling permutations and truncating unnecessary submodel training and evaluation.

- K-subset Shapley: This method [27] randomly takes every possible size subset of a participant, strictly records the occurrence time of size K, and reconstructs the participant’s Shapley Value to his expected contribution to a K-size subset with a random base. The way retains the hierarchical structure of Shapley Value, it has high approximation precision.

- SMR Shapley: Similar to the MR method in the literature [6], gradients are utilized to update subsets of the global model, thereby avoiding the need for local users to retrain and conserving computational resources. The Shapley Value of each participant is calculated in each training epoch, and the results are recorded. The sum of these contributions is aggregated to reflect the overall performance of each client across the federated training process.

- TMR Shapley: The method is the Truncated Multi-Round (TMR) construction introduced in [28], which is an improvement of the MR algorithm. It uses a decay factor and the accuracy of each round to control the weights of the round-level in the final result. Once the round-level become negligible for the final result, the model is no longer constructed or evaluated.

5.3. Performance Evaluation Metrics.

5.4. Experimental Result

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simeone, O. A very brief introduction to machine learning with applications to communication systems. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking 2018, 4, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, B.; Tiwari, P.; Ning, X.; Muhammad, K. Quantum detectable Byzantine agreement for distributed data trust management in blockchain. Information Sciences 2023, 637, 118909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, J.; Sun, H.; Li, T.; Li, Z. WTDP-Shapley: Efficient and effective incentive mechanism in federated learning for intelligent safety inspection. IEEE Transactions on Big Data 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Liu, H.; Jia, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. Incentivizing proportional fairness for multi-task allocation in crowdsensing. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Tong, Y.; Wei, S. Profit allocation for federated learning. 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE, 2019, pp. 2577–2586.

- Hussain, G.J.; Manoj, G. Federated learning: A survey of a new approach to machine learning. 2022 First International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Information and Communication Technologies (ICEEICT). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–8.

- FedAI. Online. Available at https://www.fedai.org.

- Xiao, Z.; Fang, H.; Jiang, H.; Bai, J.; Havyarimana, V.; Chen, H.; Jiao, L. Understanding private car aggregation effect via spatio-temporal analysis of trajectory data. IEEE transactions on cybernetics 2021, 53, 2346–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström, H.; da Silva Jr, J.M.B.; Amiri, M.M.; Chen, M.; Fodor, V.; Poor, H.V.; Fischione, C.; others. Wireless for machine learning: A survey. Foundations and Trends® in Signal Processing 2022, 15, 290–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, H.; Wen, W.; Xia, W.; Wang, B.; Zhu, H. Contract Theory Based Incentive Mechanism for Clustered Vehicular Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Xu, M.; Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Feddisco: Federated learning with discrepancy-aware collaboration. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 39879–39902.

- Yong, W.; Guoliang, L.; Kaiyu, L. Survey on contribution evaluation for federated learning. Journal of Software 2022, 34, 1168–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Clauset, A. Inference, models and simulation for complex systems. Lecture Notes CSCI 2011, 70001003. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, F.; Wiedemann, S.; Müller, K.R.; Samek, W. Robust and communication-efficient federated learning from non-iid data. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2019, 31, 3400–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L. A value for n-person games. <italic>Classics in Game Theory</italic> <bold>2020</bold>, pp. 69–79.

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Cui, L. Gtg-shapley: Efficient and accurate participant contribution evaluation in federated learning. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2022, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, Z.; Zhong, D.; Li, C.; Yuan, Y. Shapley-value-based Contribution Evaluation in Federated Learning: A Survey. 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Digital Twins and Parallel Intelligence (DTPI). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Verbraeken, J.; Wolting, M.; Katzy, J.; Kloppenburg, J.; Verbelen, T.; Rellermeyer, J.S. A survey on distributed machine learning. Acm computing surveys (csur) 2020, 53, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE signal processing magazine 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learning, F. Collaborative machine learning without centralized training data. Publication date: Thursday, April 2017, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Uprety, A.; Rawat, D.B.; Li, J. Privacy preserving misbehavior detection in IoV using federated machine learning. 2021 IEEE 18th annual consumer communications & networking conference (CCNC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–6.

- Lyu, L.; Xu, X.; Wang, Q.; Yu, H. Collaborative fairness in federated learning. <italic>Federated Learning: Privacy and Incentive</italic> <bold>2020</bold>, pp. 189–204.

- Kearns, M.; Ron, D. Algorithmic stability and sanity-check bounds for leave-one-out cross-validation. Proceedings of the tenth annual conference on Computational learning theory, 1997, pp. 152–162.

- Ghorbani, A.; Zou, J. Data shapley: Equitable valuation of data for machine learning. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 2242–2251.

- Wang, G.; Dang, C.X.; Zhou, Z. Measure contribution of participants in federated learning. 2019 IEEE international conference on big data (Big Data). IEEE, 2019, pp. 2597–2604.

- Jia, R.; Dao, D.; Wang, B.; Hubis, F.A.; Hynes, N.; Gürel, N.M.; Li, B.; Zhang, C.; Song, D.; Spanos, C.J. Towards efficient data valuation based on the shapley value. The 22nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics. PMLR, 2019, pp. 1167–1176.

- Wei, S.; Tong, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Song, T. Efficient and Fair Data Valuation for Horizontal Federated Learning. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, <italic>10</italic>, 139–152. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Niyato, D.; Xie, S.; Zhang, J. Incentive mechanism for reliable federated learning: A joint optimization approach to combining reputation and contract theory. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2019, 6, 10700–10714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Niyato, D.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guizani, M. Reliable federated learning for mobile networks. IEEE Wireless Communications 2020, 27, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, S.; Jin, Y. Federated learning on non-IID data: A survey. Neurocomputing 2021, 465, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR, 2017, pp. 1273–1282.

- Castro, J.; Gómez, D.; Tejada, J. Polynomial calculation of the Shapley value based on sampling. Computers & Operations Research 2009, 36, 1726–1730. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Hou, Z.; Guo, S.; Chen, H.; Li, Z. SWATM: Contribution-Aware Adaptive Federated Learning Framework Based on Augmented Shapley Values. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME). IEEE, 2023, pp. 672–677.

- Dong, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yassine, A.; Hossain, M.S. Affordable federated edge learning framework via efficient Shapley value estimation. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 147, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Cortes, C.; Burges, C. MNIST handwritten digit database. ATT Labs [Online]. Available: http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist 2010, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Qu, Z.; Zeng, D.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Akerkar, R. Adaptive federated learning on non-iid data with resource constraint. IEEE Transactions on Computers 2021, 71, 1655–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Time | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Exact Shapley[25] | 10840.24s | 84.93% |

| TMC Shapley[25] | 720.56s | 86.95% |

| K-subset Shapley[27] | 601.76s | 86.87% |

| SMR Shapley[6] | 636.94s | 86.70% |

| TMR Shapley[28] | 574.05s | 86.69% |

| Ours | 646.35s | 90.64% |

| Name | Time | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Exact Shapley[25] | 11570.86s | 85.43% |

| TMC Shapley[25] | 737.58s | 86.71% |

| K-subset Shapley[27] | 630.42s | 86.32% |

| SMR Shapley[6] | 600.94s | 86.83% |

| TMR Shapley[28] | 587.43s | 86.72% |

| Ours | 729.98s | 88.38% |

| Name | Time | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Exact Shapley[25] | 10865.56s | 84.42% |

| TMC Shapley[25] | 659.58s | 85.53% |

| K-subset Shapley[27] | 679.24s | 85.72% |

| SMR Shapley[6] | 695.14s | 85.83% |

| TMR Shapley[28] | 564.35s | 85.68% |

| Ours | 655.78s | 86.96% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).