Submitted:

30 May 2024

Posted:

31 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

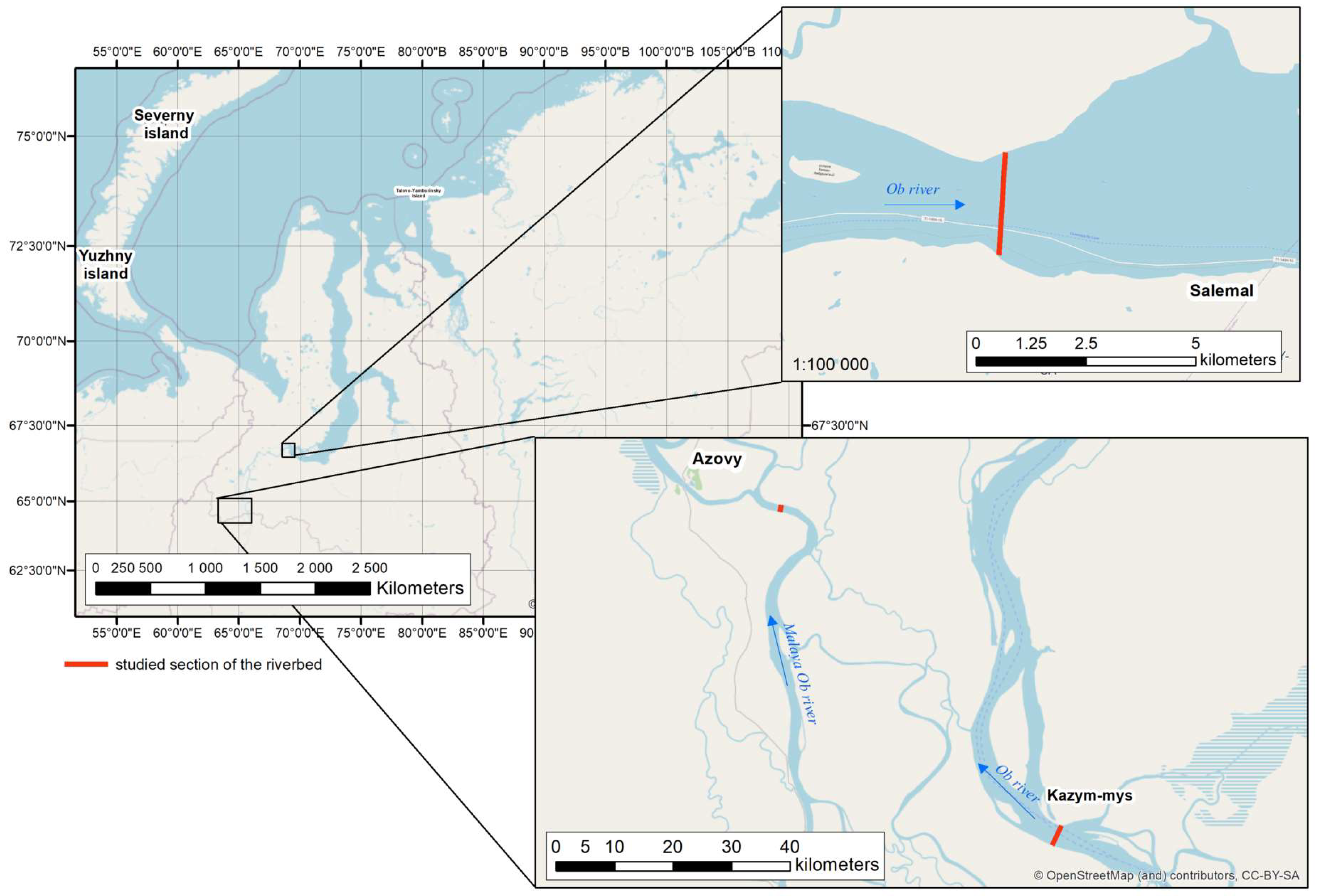

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling and Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Physico-Chemical Parameters

3.2. Elemental Composition of the Dissolved Fraction

3.3. Concentrations of Suspended Elements

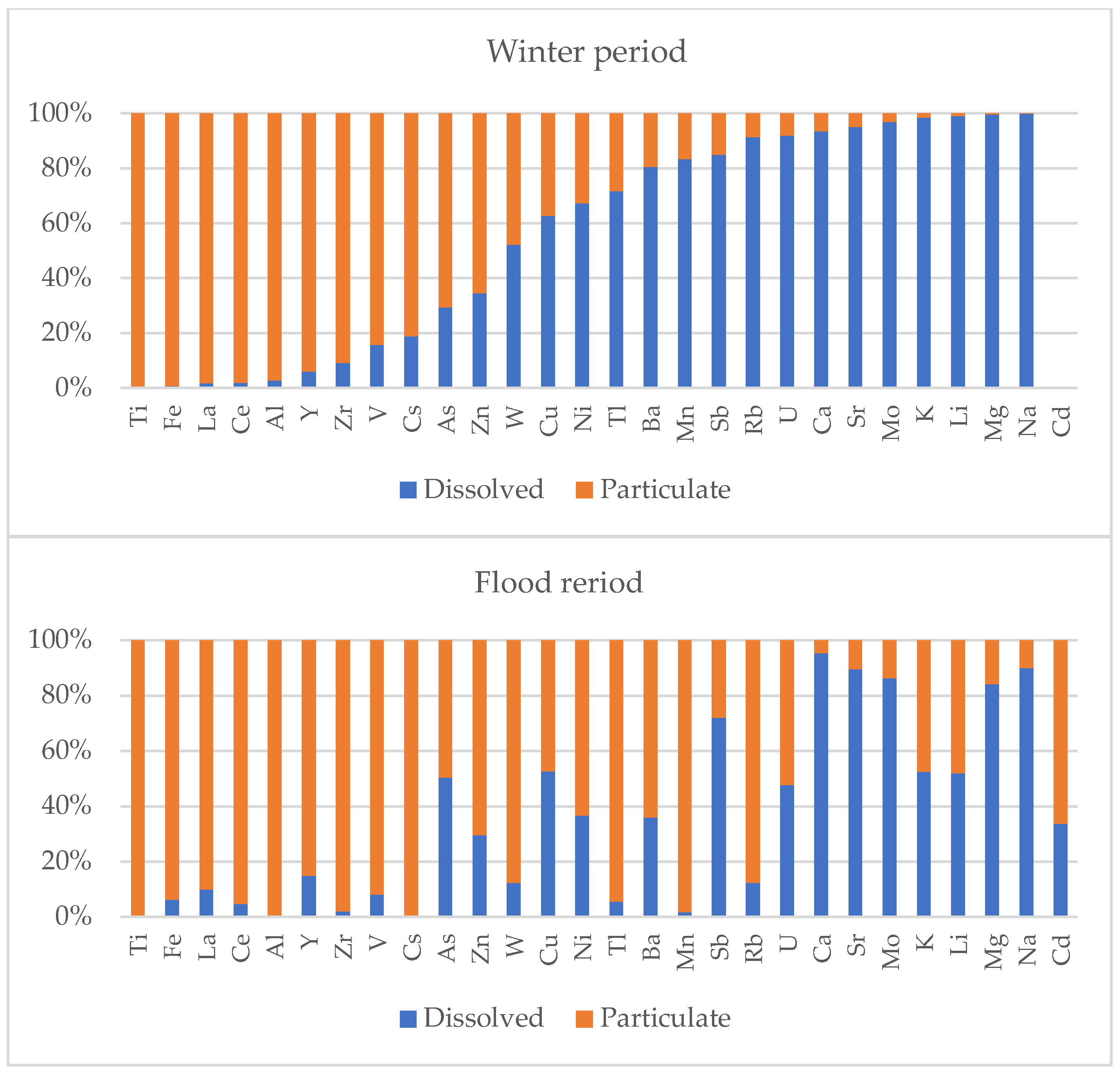

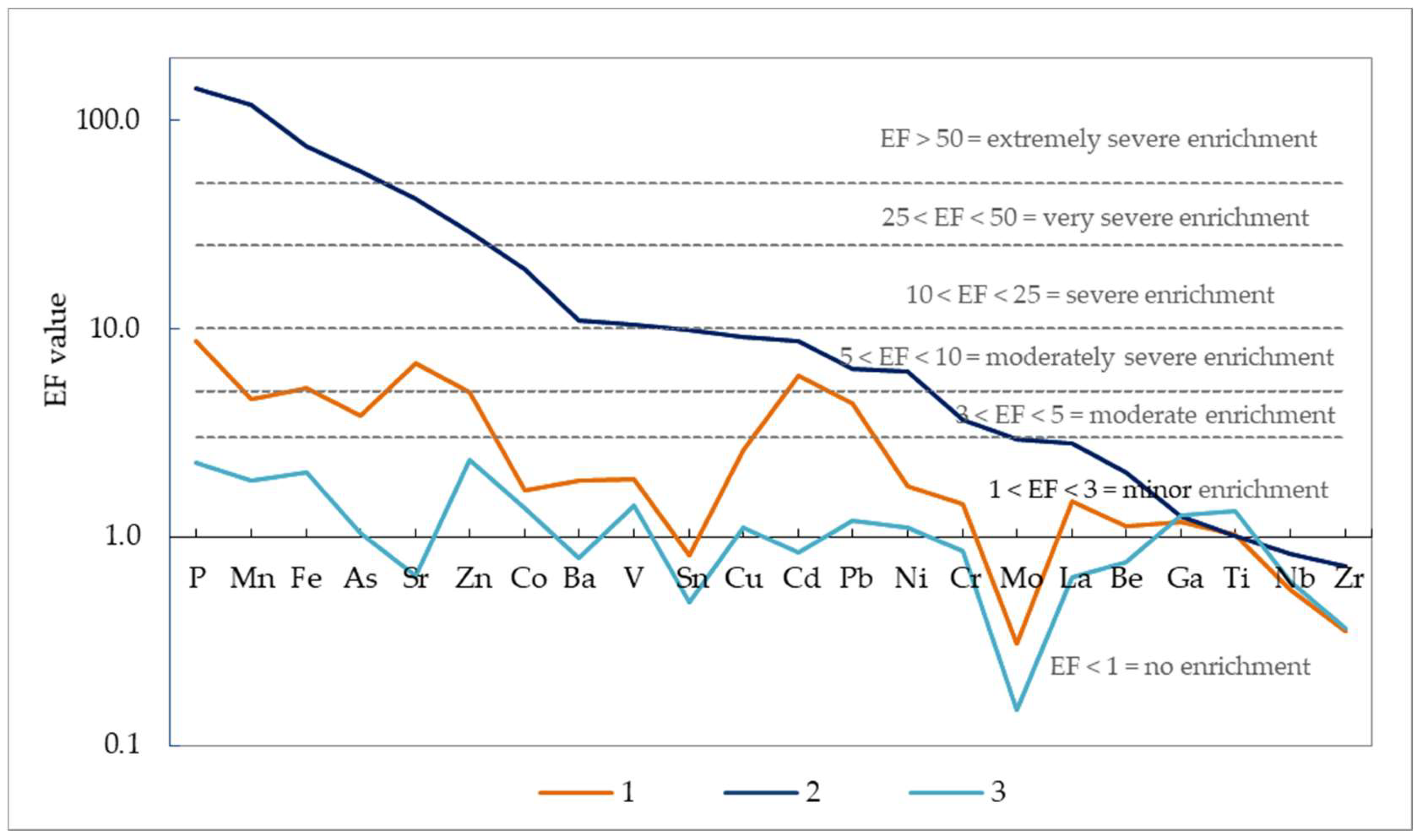

3.4. Composition of Suspended Matter

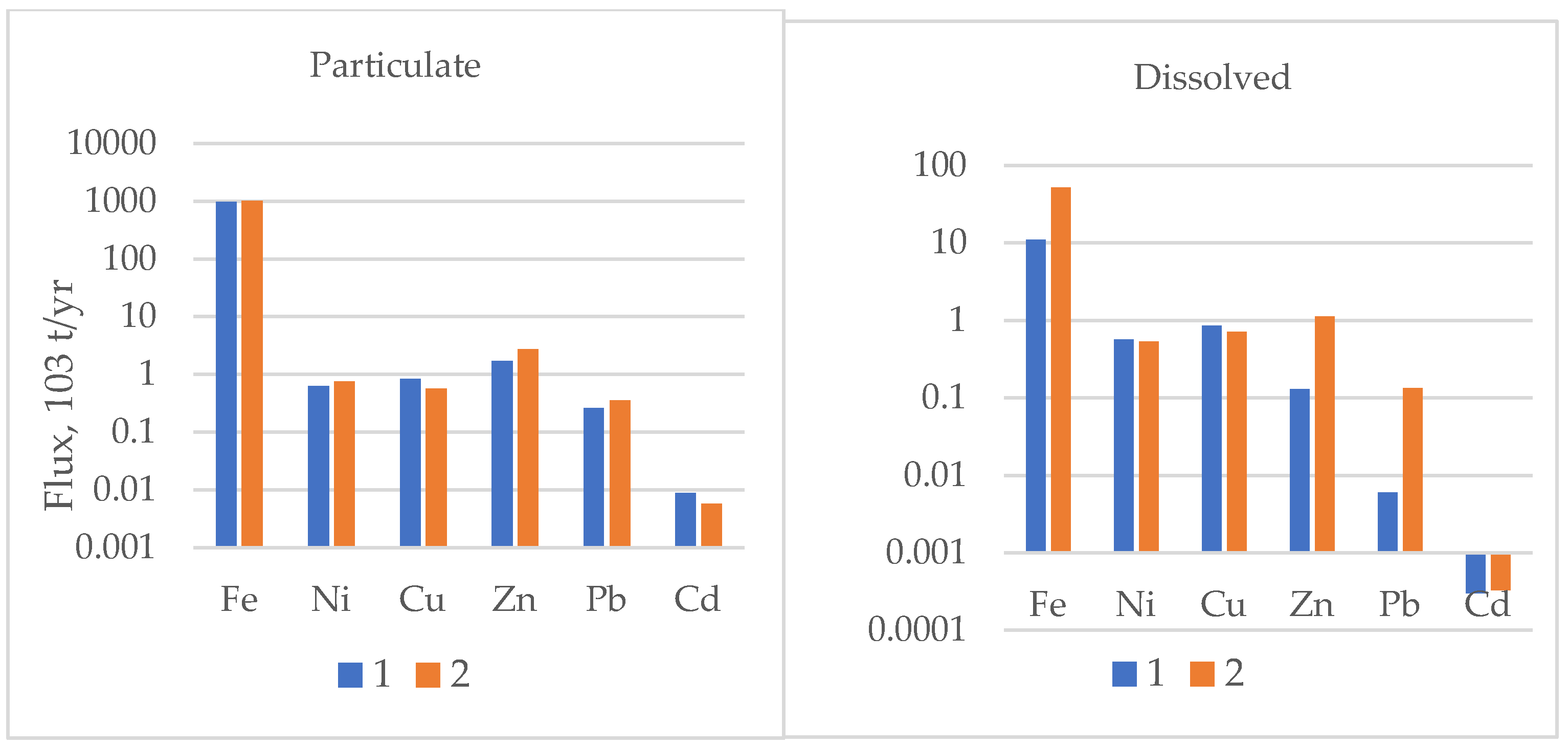

3.5. Element Transport

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- White, D.; Hinzman, L.; Alessa, L.; et al. The Arctic Freshwater System: Changes and Impacts. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, G04S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiklomanov, A.I.; Lammers, R.B.; Rawlins, M.A.; Smith, L.C.; Pavelsky, T.M. Temporal and Spatial Variations in Maximum River Discharge From a Bew Russan Dataset J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, V.V.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Zhulidov, A.V.; Filippov, A.S.; Gurtovaya, T.Y.; Holmes, R.M.; Kosmenko, L.S.; McClelland, J.W.; Peterson, B.J.; Tank, S.E. Dissolved Major and Trace Elements in the Largest Eurasian Arctic Rivers: Ob, Yenisey, Lena, and Kolyma. Water 2024, 16, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiklomanov, I.A.; Shiklomanov, A.I.; Lammers, R.B.; Peterson, B.J.; Vorosmarty, C.J. The Dynamics of River Water Inflow to the Arctic Ocean. In The Freshwater Budget of the Arctic Ocean. NATO Science Series (Series 2. Environment Security); Lewis, E.L., Jones, E.P., Lemke, P., Prowse, T.D., Wadhams, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, V.P.; Pikinerov, P.V.; Gennadinik, V.B.; Babushkin, A.G.; Moskovchenko, D.V. Runoff over Siberian river basins as an integrate proxy of permafrost state. Doklady Earth Sci. 2019, 487, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovsky, O.S.; Manasypov, R.M.; Kopysov, S.; Krickov, I.V.; Shirokova, L.S.; Loiko, S.V.; Lim, A.G.; Kolesnichenko, L.G.; Vorobyev, S.N.; Kirpotin, S.N. Impact of permafrost thaw and climate warming on riverine export fluxes of carbon, nutrients and metals in western Siberia. Water 2020, 12, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnichenko, I.; Kolesnichenko, L.G.; Vorobyev, S.N.; Shirokova, L.S.; Semiletov, I.P.; Dudarev, O.V.; Vorobev, R.S.; Shavrina, U.; Kirpotin, S.N.; Pokrovsky, O.S. Landscape, soil, lithology, climate and permafrost control on dissolved carbon, major and trace elements in the Ob River, Western Siberia. Water 2021, 13, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoroshavin, V.Y.; Moiseenko, T.I. Petroleum hydrocarbon runoff in rivers flowing from oil and gas producing regions in Northwestern Siberia. Water Resour. 2014, 41, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskovchenko, D.V.; Babushkin, A.G.; Yurtaev, A.A. The impact of the Russian oil industry on surface water quality (a case study of the Agan River catchment, West Siberia). Environ. Earth Sci., 2020, 79, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surface Water Resources of the USSR, Volume. 15; Altai and Western Siberia. Issue 2: Middle Ob. N.A. Panina, Ed., Leningrad: Gidrometeoizdat, 1972. (in Russian).

- Gordeev, V.V.; Martin, J.-M.; Sidorov, I.S.; Sidorova, M.V. A reassessment of the Eurasian river input of water, sediment, major elements, and nutrients to the Arctic Ocean. Am. J. Sci. 1996, 296, 664–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.M.; Peterson, B.J.; Gordeev, V.V.; Zhulidov, A.V.; Meybeck, M.; Lammers, R.B.; Vorosmarty, C. J. Flux of nutrients from Russian rivers to the Arctic Ocean: Can we establish a baseline against which to judge future changes? Water Resour. Res. 2000, 36, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.M.; McClelland, J.W.; Peterson, B.J.; Tank, S.E.; Bulygina, E.; Eglinton, T.I.; Gordeev, V.V.; Gurtovaya, T.Y.; Raymond, P.A.; Repeta, D.J.; Staples, R.; Stiegl, R.G.; Zhulidov, A.V.; Zimov, S.A. Seasonal and Annual Fluxes of Nutrients and Organic Matter from Large Rivers to the Arctic Ocean and Surrounding Seas. Estuaries and Coasts 2012, 35, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, V.V. River Input of Water, Sediment, Major Ions, Nutrients and Trace Metals from Russian Territory to the Arctic Ocean. In The Freshwater Budget of the Arctic Ocean. NATO Science Series. Lewis, E.L., Jones, E.P., Lemke, P., Prowse, T.D., Wadhams, P.; Eds., Springer, Dordrecht, 2000, Volume 70, pp. 297–322. [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, V.V.; Rachold, V.; Vlasova, I.E. Geochemical Behaviour of Major and Trace Elements in Suspended Particulate Material of the Irtysh River, the Main Tributary of the Ob River, Siberia. J. Appl. Geochem. 2004, 19, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, V.V.; Beeskow, B.; Rachold, V. Geochemistry of the Ob and Yenisey estuaries: A comparative study. Ber. Polarforsch. Meeresforsch (Reports on Polar and Marine Research) 2007, 565, 235. [Google Scholar]

- Gordeev, V.V.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Zhulidov, A.V.; Filippov, A.S.; Gurtovaya, T.Y.; Holmes, R.M.; Kosmenko, L.S.; McClelland, J.W.; Peterson, B.J.; Tank, S.E. Dissolved Major and Trace Elements in the Largest Eurasian Arctic Rivers: Ob, Yenisey, Lena, and Kolyma. Water 2024, 16, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demina, L.L.; Gordeev, V.V.; Galkin, S.V.; Kravchishina, M.D.; Aleksankina, S.P. The Biogeochemistry of Some Heavy Metals and Metalloids in the Ob River Estuary–Kara Sea Section. Oceanology 2010, 50, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savenko, A.V.; Savenko, V.S. Trace Element Composition of the Dissolved Matter Runoff of the Russian Arctic Rivers. Water 2024, 16, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovsky, O.S.; Manasypov, R.M.; Loiko, S. V.; Krickov, I. A.; Kopysov, S. G.; Kolesnichenko, L. G.; Vorobyev, S. N.; and Kirpotin, S. N. Trace element transport in western Siberian rivers across a permafrost gradient. Biogeosciences 2016. 13, 1877–1900. [CrossRef]

- McClelland, J.W.; Tank, S.E.; Spencer, R.G.M.; Shiklomanov, A.I.; Zolkos, S.; Holmes, R.M. Arctic Great Rivers Observatory. Water Quality Dataset. Version 20230314. Available online: https://arcticgreatrivers.org/data (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Syso, A.I. General regularities of the distribution of microelements in the surface deposits and soils of West Siberia. Contemporary Problems of Ecology 2004, 11, 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Opekunova, M.G.; Opekunov, A.Y.; Kukushkin, S.Y.; Ganul, A.G. Background Contents of Heavy Metals in Soils and Bottom Sediments in the North of Western Siberia. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syso, A.I. Patterns of Distribution of Chemical Elements in Soil-Forming Rocks and Soils of Western Siberia. Publishing House of SB RAS, Novosibirsk, 2007. (In Russian).

- Vinokurov, Y.I.; Tsymbaley, Y.M.; Zinchenko, G.S.; Stoyasheva, N.V. General Characteristics of the Ob basin. In The Current State of Water Resources and the Functioning of the Water Management Complex of the Ob and Irtysh Basin; Vinokurov, Y.I., Puzanov, A.V., Bezmaternykh, D.M., Eds.; Publishing House SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia, 2012; pp. 9–11. (In Russian).

- Soromotin, A.; Moskovchenko, D.; Khoroshavin, V.; Prikhodko, N.; Puzanov, A.; Kirillov, V.; Koveshnikov, M.; Krylova, E.; Krasnenko, A.; Pechkin, A. Major, Trace and Rare Earth Element Distribution in Water, Suspended Particulate Matter and Stream Sediments of the Ob River Mouth. Water 2022, 14, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-García, S.S; Pérez-Escamilla, P.A.; Sujitha, S.B. ; Godwyn-Paulson, P,.;Zúñiga-Cabezas, A.F.; Jonathan, M.P. Geochemical elements in suspended particulate matter of Ensenada de La Paz Lagoon, Baja California Peninsula, Mexico: Sources, distribution, mass balance and ecotoxicological risks. J Environ Sci (China) 2024, 136, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Z. Heavy metals in suspended particulate matter in the Yarlung Tsangpo River, Southwest China. Geosystems and Geoenvironment 2024, 3, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niencheski, L.F.; Baumgarten, M.G.Z. Distribution of particulate trace metal in the southern part of the Patos Lagoon estuary. Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management 2000, 3, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskovchenko, D.; Shamilishvilly., G.; Abakumov, E. Soil biogeochemical features of Nadym-Purovskiy province (Western Siberia), Russia. Ecologia Balkanica 2019, 11, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Sakan, S.M.; Dordević, D.S.; Manojlović, D.D.; Predrag, P.S. Assessment of heavy metal pollutants accumulation in the Tisza river sediments. J Environ Manage 2009, 90, 3382–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Water quality standards for water bodies of fishery importance (In Russian). Available online: https://base.garant.ru/71586774/53f89421bbdaf741eb2d1ecc4ddb4c33 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Uvarova, V.I. Contemporary Status of the Water Quality in the Ob River Within Tymen’ Oblast. Vestn. Ekologii, Lesovedeniya Landshaftovedeniya 2000, 1, 18–26. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Babushkin, A.G.; Moskovchenko, D.V.; Pikunov, S.V. Hydrochemical Monitoring of the Surface Waters of the Khanty-Mansiisk Autonomous Okrug—Yugra. Nauka Publ: Novosib. Russ. 2007, 152 p. (In Russian).

- Papina, T.S.; Galakhov, V.P.; Tsymbaley, Y.M.; et al. Comprehensive Assessment of Water-Resource and Water-Ecological Potential. In The Current State of Water Resources and the Functioning of the Water Management Complex of the Ob and Irtysh Basin; Vinokurov, Y.I., Puzanov, A.V., Bezmaternykh, D.M., Eds.; Publishing House SB RAS: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2012; pp. 61–92. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Magritsky, D.V.; Chalov, S.R.; Agafonova, S.A. Hydrological Regime of The Lower Ob in Modern Hydroclimatic Conditions and Under the Influence of Large-Scale Water Management. Sci. Bull. Yamalo-Nenets Auton. Okrug. 2019, 1, 106–115. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krickov, I.V.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Manasypov, R. M.; Lim, A.G.; Shirokova, L.S.; Viers, J. Colloidal transport of carbon and metals by western Siberian rivers during different seasons across a permafrost gradient. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2019, 265, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magritsky, D.V.; Frolova, N.L.; Evstigneev, V.M.; Povalishnikova, E.S.; Kireeva, M.B.; Pakhomova, O.M. Long-Term Changes of River Water Inflow into the Seas of the Russian Arctic Sector. Polarforschung 2017, 87, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkova, G.; Drozdov, D.; Vasiliev, A.; Gravis, A.; Kraev, G.; Korostelev, Y.; Nikitin, K.; Orekhov, P.; Ponomareva, O.; Romanovsky, V.; et al. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Permafrost in the Western Part of the Russian Arctic. Energies 2022, 15, 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papina, T.S.; Eirikh, A.N.; Serykh, T.G.; Dryupina, E.Y. Space and Time Regularities in the Distribution of Dissolved and Suspended Manganese Forms in Novosibirsk Reservoir Water. Water Resour. 2017, 44, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovsky, O.S.; Manasypov, R.M.; Chupakov, A.V.; Kopysov, S. Element transport in the Taz River, Western Siberia. Chem. Geol. 2022, 614, 121180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, V.P.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Vorobyev, S.; Krickov, I.V.; Manasypov, R.M.; Politova, N.V.; Kopysov, S.G.; Dara, O.M.; Auda, Y.; Shirokova, L.S.; et al. Impact of snow deposition on major and trace element concentrations and elementary fluxes in surface waters of the Western Siberian Lowland across a 1700 km latitudinal gradient. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 5725–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskovchenko, D.V. Biogeochemical Properties of the High Bogs in Western Siberia. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 2006, 1, 63–70. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Viers, J.; Dupre, B.; Gaillardet, J. Chemical Composition of Suspended Sediments in World Rivers: New Insights from A New Database. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordeev, V.V.; Lisitzin, A.P. Geochemical interaction between the freshwater and marine hydrospheres. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2014, 55, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drits, A.V.; Kravchishina, M.D.; Sukhanova, I.N.; et al. Seasonal variability in the sedimentary matter flux on the shelf of the northern Kara Sea. Oceanology 2021, 61, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalov, G.S.; Ivanova, A.A.; Kolesnikov, T.H. Dissolved and Particulate Forms of Trace Elements in The Main Rivers of the USSR. In Geochemistry of Sedimentary Rocks and Ores; Strakhov, N.M., Ed.; Nauka Publishing: Moscow, Russia, 1968; Volume 5, pp. 72–87. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Krickov, I.V.; Lim, A.G.; Manasypov, R.M.; Loiko, S.V.; Vorobyev, S.N.; Shevchenko, V.P.; Dara, O.M.; Gordeev, V.V.; Pokrovsky, O.S. Major and trace elements in suspended matter of Western Siberian rivers: first assessment across permafrost zones and landscape parameters of watersheds. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 269, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krickov, I.V.; Lim, A.G.; Shevchenko, V.P.; Starodymova, D.P.; Dara, O.M.; Kolesnichenko, Y.; Zinchenko, D.O.; Vorobyev, S.N.; Pokrovsky, O.S. Seasonal Variations of Mineralogical and Chemical Composition of Particulate Matter in a Large Boreal River and Its Tributaries. Water 2023, 15, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symader, W.; Strunk, N. Determining the source of suspended particulate material, erosion, debris flows and environment in mountain regions. In Proceedings of the Chengdu symposium, July 1992. IAHS Publ. no. 209. 1992.

- Lanzerstorfer, C. Heavy metals in the finest size fractions of road-deposited sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 239, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudry, M.A.; Zwolsman, J.J.G. Seasonal dynamics of dissolved trace metals in the scheldt estuary: Relationship with redox conditions and phytoplankton activity. Estuaries and Coasts 2008, 31, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viers, J.; Dupre, B.; Gaillardet, J. Chemical Composition of Suspended Sediments in World Rivers: New Insights from A New Database. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papina, T.S. Ecological–Analytical Studies of Heavy Metals in Water Ecosystems of Ob River Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia, 2004. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T.H.; Lin, C.L. Dissolved and particulate trace metals and their partitioning in a hypoxic estuary: the Tanshui estuary in northern Taiwan. Estuaries 2002, 25(4), 598–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.L.; Kessarkar, P.M.; Purnachandra Rao, V.; Suja, S.; Parthibana, G.; Kurian, S. Seasonal distribution of trace metals in suspended particulate and bottom sediments of four microtidal river estuaries, west coast of India. Hydrol Sci J. 2019, 64, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovsky, O.S.; Viers, J.; Shirokova, L.S.; Shevchenko, V.P.; Filipov, A.S.; Dupr´e, B. Dissolved, suspended, and colloidal fuxes of organic carbon, major and trace elements in Severnaya Dvina River and its tributary. Chem. Geol. 2010, 273, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMAP Assessment 2002: Heavy Metals in the Arctic. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Oslo, Norway. 2005.

- Pokrovsky, O.S. Measuring and Estimating Fluxes of Carbon, Major and Trace Elements to the Arctic Ocean. In: Novel Methods for Monitoring and Managing Land and Water Resources in Siberia. Mueller L., Sheudshen A., Eulenstein F., Eds.; Springer, Cham. 2016, pp. 185–212. [CrossRef]

- Stepanova, V.A.; Pokrovsky, O.S.; Viers, J.; Mironycheva-Tokareva, N.P.; Kosykh, N.P.; Vishnyakova, E.K. Elemental Composition of Peat Profiles in Western Siberia: Effect of the Micro-Landscape, Latitude Position and Permafrost Coverage. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 53, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | 2020 | 2022 | 2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition to autumn low flow | Flooding | Winter low flow | Flooding | |||||||

| S | K | A | S | K | A | S | K | A | S | |

| pH | 8.01 | 7.09 | 7.04 | 7.19 | 7.19 | 6.92 | 7.15 | 7.76 | 7.68 | 7.69 |

| Color index | 87 | 91 | 85 | 83 | 13 | 11 | 14 | 43 | 45 | 44 |

| DO, mg O2 L-1 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 10.7 |

| TDS, mg L-1 | 116.0 | 62.5 | 58.4 | 60.7 | 145 | 151 | 168 | 70.3 | 70.5 | 74.0 |

| TSS, mg L-1 | 21.0 | 58 | 86 | 65 | 29 | 30 | 11 | 69 | 61 | 40.0 |

| Elements | Dissolved | Particulate | Total | ||||||||||||

| Summer –autumn, | Spring flood | Winter | Year | Yields, | Summer - autumn,10 3 tons | Spring flood,10 3 tons | Winter,10 3 tons | Year,10 3 tons | Yields,kg km−2 y−1 | Summer - autumn,10 3 tons | Spring flood kg km−2 y−1 | Winter kg km−2 y−1 | Year kg km−2 y−1 | Yields,kg km−2 y−1 | |

| 10 3 tons | kg km−2 y−1 | 10 3 tons | kg km−2 y−1 | 10 3 tons | kg km−2 y−1 | ||||||||||

| B | 1.4 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 8.6 | 2.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 44.7 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 8.6 | 2.9 |

| Na | 442 | 1122 | 1088 | 2652 | 887 | 4.9 | 126 | 3.0 | 134 | 49.4 | 447 | 1248 | 1091 | 2785 | 932 |

| Mg | 304 | 720 | 744 | 1768 | 591 | 9.5 | 135 | 3.5 | 148 | 334.8 | 314 | 855 | 747 | 1916 | 641 |

| Al | 0.8 | 2.9 | 0.2 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 36.5 | 958 | 6.7 | 1001 | N/A | 37 | 961 | 6.8 | 1005 | 336 |

| Si | 156 | 626 | 676 | 1458 | 488 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 11.8 | N/A | 626 | N/A | 626.0 | 209 |

| P | 1.2 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 21.4 | 10.7 | 35.3 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 26 | 11 | 41 | 13.6 |

| S | 145 | 571 | 376 | 1091 | 365 | 2.2 | 9.4 | 5.3 | 16.8 | 72.4 | 147 | 580 | 381 | 1108 | 371 |

| K | 58 | 229 | 109 | 396 | 132 | 7.1 | 208 | 1.8 | 216 | 176 | 65 | 437 | 110 | 612 | 205 |

| Ca | 955 | 2862 | 2910 | 6727 | 2250 | 188 | 138 | 201 | 527 | 22.9 | 1143 | 3000 | 3111 | 7254 | 2426 |

| Ti | 0.02 | 0.11 | N/A | 0.13 | 0.043 | 2.0 | 66.1 | 0.4 | 68.4 | 0.66 | 2.0 | 66.2 | 0.40 | 68.5 | 23.0 |

| V | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.075 | 0.09 | 1.79 | 0.10 | 1.98 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 1.9 | 0.12 | 2.2 | 0.74 |

| Cr | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.08 | 1.28 | 0.04 | 1.39 | 11.0 | 0.09 | 1.28 | 0.04 | 1.39 | 0.47 |

| Mn | 0.03 | 0.36 | 50 | 51 | 17.0 | 2.0 | 20.9 | 10.1 | 33.0 | 339 | 2.1 | 21 | 60 | 84 | 28.0 |

| Fe | 1.0 | 49 | 1.3 | 52 | 17.3 | 70 | 743 | 201 | 1014 | 0.10 | 71 | 792 | 203 | 1066 | 356 |

| Co | 0.002 | N/A | 0.042 | 0.044 | 0.015 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.015 | 0.27 | 0.068 | 0.31 | 0.10 |

| Ni | 0.082 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 1.1 | 0.08 | 1.3 | 0.43 |

| Cu | 0.11 | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.71 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.15 | 1.0 | 0.08 | 1.3 | 0.43 |

| Zn | 0.038 | 0.96 | 0.12 | 1.1 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 2.28 | 0.23 | 2.70 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 3.8 | 1.3 |

| As | 0.068 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 1.3 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.58 | 0.2 |

| Sr | 6.3 | 18 | 18 | 42 | 14.2 | 0.85 | 2.12 | 0.96 | 3.93 | 2.6 | 7.2 | 20 | 19 | 46 | 15.5 |

| Ba | 0.8 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 0.57 | 6.61 | 0.64 | 7.82 | 0.12 | 1.4 | 10 | 3.3 | 15 | 5.0 |

| Pb | 0.072 | 0.062 | N/A | 0.133 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.36 | N/A | 0.49 | 0.19 |

| Li | 0.17 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.982 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.42 | 0.003 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 0.87 | 0.37 | 1.42 | 0.48 |

| Rb | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.304 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 1.24 | 0.01 | 1.29 | 117 | 0.09 | 1.41 | 0.09 | 1.59 | 0.53 |

| tons | g km−2 y−1 | tons | g km−2 y−1 | tons | g km−2 y−1 | ||||||||||

| Y | 1.1 | 54.5 | 0.7 | 56.3 | 18.8 | 24.2 | 314 | 11.3 | 349 | 566 | 25 | 368 | 12 | 405 | 0.14 |

| Zr | 3.8 | 31.7 | 2.1 | 37.5 | 12.6 | 53.6 | 1618 | 20.5 | 1692 | 4.0 | 57 | 1650 | 23 | 1730 | 0.58 |

| Mo | 24.5 | 62.1 | 40.4 | 127.0 | 42.5 | 0.7 | 9.9 | 1.4 | 12 | 1.9 | 25 | 72 | 42 | 139 | 0.046 |

| Cd | 1.1 | 2.2 | N/A | 3.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 4.4 | 0.3 | 5.8 | 11 | 2.1 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 9.1 | 0.003 |

| Sb | 12.0 | 71.9 | 18.9 | 102.9 | 34.4 | 2.8 | 27.9 | 3.4 | 34.1 | 23 | 15 | 100 | 22 | 137 | 0.046 |

| Cs | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 66.4 | 0.5 | 69.5 | 107 | 2.7 | 67 | 0.6 | 70 | 0.023 |

| La | 0.5 | 31.2 | 0.2 | 31.9 | 10.7 | 26.0 | 285 | 9.6 | 321.1 | 334 | 27 | 317 | 10 | 353 | 0.12 |

| Ce | 0.8 | 46.3 | 0.4 | 47.5 | 15.9 | 50.1 | 929 | 19.3 | 998 | 142 | 51 | 975 | 20 | 1045 | 0.35 |

| Nd | 0.4 | 37.8 | 0.3 | 38.5 | 12.9 | 25.5 | 391 | 9.4 | 426 | 30 | 26 | 429 | 10 | 464 | 0.16 |

| Sm | 0.1 | 8.9 | 0.1 | 9.1 | 3.0 | 5.6 | 82.5 | 2.2 | 90.2 | 25 | 5.7 | 91 | 2.3 | 99 | 0.033 |

| Gd | 0.1 | 10.3 | 0.2 | 10.6 | 3.5 | 5.3 | 66.6 | 2.2 | 74.1 | 20 | 5.4 | 77 | 2.3 | 85 | 0.028 |

| Dy | 0.1 | 9.0 | 0.2 | 9.3 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 54.8 | 1.8 | 60.9 | 11 | 4.5 | 64 | 2.0 | 70 | 0.023 |

| Er | 0.1 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 5.8 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 30.0 | 1.1 | 33.4 | 7.5 | 2.6 | 35 | 1.2 | 39 | 0.013 |

| W | 3.7 | 2.9 | 0.9 | 7.4 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 20.7 | 0.8 | 22.5 | 2.1 | 4.7 | 24 | 1.7 | 30 | 0.010 |

| Tl | 0.07 | 0.3 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 6.3 | 0.2 | 6.7 | 0.002 |

| Bi | 0.06 | 0.9 | N/A | 1.0 | 0.33 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 0.13 | 5.7 | 41.1 | 0.9 | 5.6 | 0.13 | 6.7 | 0.002 |

| Th | 0.11 | 4.3 | N/A | 4.5 | 1.5 | 5.5 | 116 | 1.6 | 123 | 12.3 | 5.6 | 120 | 1.6 | 127 | 0.043 |

| U | 17.3 | 28.0 | 49.8 | 95.1 | 31.8 | 1.6 | 30.7 | 4.4 | 36.7 | 44.7 | 19 | 59 | 54 | 132 | 0.044 |

| Elements | Data source and water body | ||

| Gordeev et al. (2024), Ob River [3] | Ob River tributaries [20] | 3 – present study, Ob River | |

| B | 2.5 | 4.3 | 2.88 |

| Al | 1.0 | 8.5 | 1.31 |

| Ti | 0.032 | 0.2 | 0.04 |

| V | 0.065 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Mn | 7.4 | 49 | 17.0 |

| Fe | 10.9 | 211 | 17.3 |

| Co | 0.019 | 0.17 | 0.015 |

| Ni | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.18 |

| Cu | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.24 |

| Zn | 0.175 | 4.2 | 0.38 |

| As | 0.1 | 0.19 | 0.10 |

| Sr | 12.2 | 14 | 14.2 |

| Rb | 0.056 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Y | 0.0084 | 0.019 | |

| Zr | 0.0096 | 0.033 | 0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).