Submitted:

29 May 2024

Posted:

30 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Studies

2.2. Mammary Gland Dissociation

2.3. Cell Culture and Transfection Experiments

2.4. Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

2.5. Immunocytochemistry

2.6. Alkaline Comet and FLARE Assays

2.7. ROS Assay

2.8. Western Blots

2.9. Quantitative Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.10. Glutathione Assay

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Acrylamide Does Not Enhance Obesity-Associated Changes to the Mammary Gland

3.2. Acrylamide Induces Systemic Changes in CYP2E1 Expression and DNA Damage

3.3. Acrylamide Exacerbates DNA Damage and Apoptosis in Mammary Glands from Obese Mice

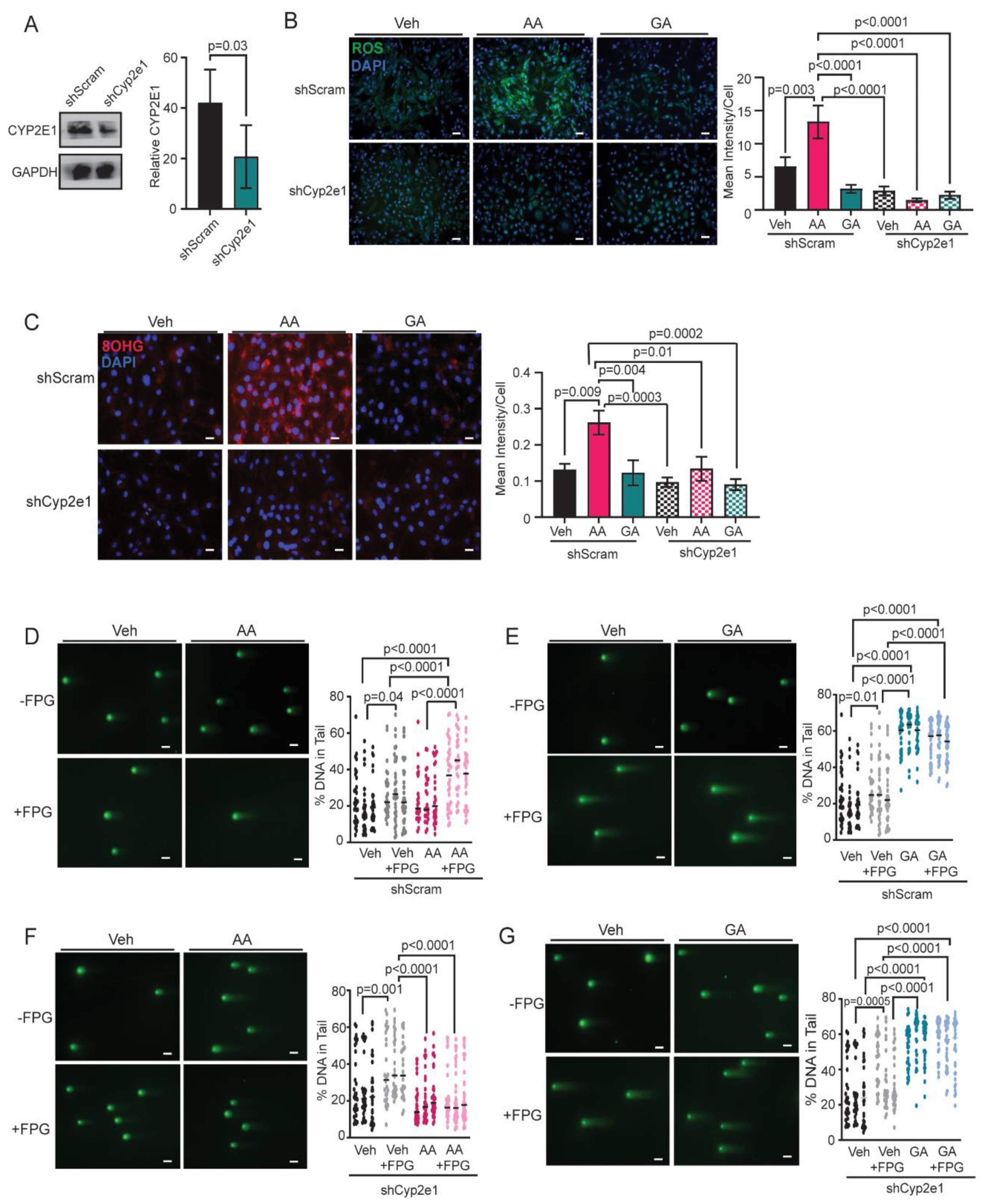

3.4. Glycidamide Increases Single and Double Strand DNA Breaks, but Acrylamide Enhances Oxidative Stress and Oxidative DNA Damage in COMMA-D Cells

3.5. Knockdown of CYP2E1 in COMMA-D Cells Rescues Acrylamide-Induced Oxidative Stress and Oxidative DNA Damage

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2022-2024. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-figures.html. Accessed on 04/28/2024.

- Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer? https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/risk_factors.htm. Accessed on 04/28/2024.

- Nindrea, R.D.; Aryandono, T.; Lazuardi, L. Breast cancer risk from modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors among women in Southeast Asia: A meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2017, 18, 3201–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.L.; Ross, R.K.; Paganini-Hill, A.; Bernstein, L. Effect of family history, obesity and exercise on breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. Int J Cancer 2003, 106, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandera, E.V.; Chandran, U.; Hong, C.C.; Troester, M.A.; Bethea, T.N.; Adams-Campbell, L.L.; Haiman, C.A.; Park, S.Y.; Olshan, A.F.; Ambrosone, C.B. , et al. Obesity, body fat distribution, and risk of breast cancer subtypes in African American women participating in the AMBER Consortium. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015, 150, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed on 04/28/2024.

- Persson, L.; Carney Almroth, B.M.; Collins, C.D.; Cornell, S.; de Wit, C.A.; Diamond, M.L.; Fantke, P.; Hassellöv, M.; MacLeod, M.; Ryberg, M.W.; et al. Outside the safe operating space of the planetary boundary for novel entities. Environ Sci Technol 2022, 56, 1510–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkoz, F.P.; Solak, M.; Petekkaya, I.; Keskin, O.; Kertmen, N.; Sarici, F.; Arik, Z.; Babacan, T.; Ozisik, Y.; Altundag, K. The prognostic impact of obesity on molecular subtypes of breast cancer in premenopausal women. J BUON 2013, 18, 335–341. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, S.; Erdem, G.U.; Karatas, F.; Aytekin, A.; Sever, A.R.; Ozisik, Y.; Altundag, K. The association between body mass index and immunohistochemical subtypes in breast cancer. Breast 2017, 32, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F. Association of physical weight statuses defined by body mass index (BMI) with molecular subtypes of premenopausal breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouckaert, O.; Van Asten, K.; Laenen, A.; Soubry, A.; Smeets, A.; Nevelstreen, I.; Vergote, I.; Wildiers, H.; Paridaens, R.; Van Limbergen, E.; et al. Body mass index, age at breast cancer diagnosis, and breast cancer subtype: a cross-sectional study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018, 168, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhouser, M.L.; Aragaki, A.K.; Prentice, R.L.; Manson, J.E.; Chlebowski, R.; Carty, C.L.; Ochs-Balcom, H.M.; Thomson, C.A.; Caan, B.J.; Tinker, L.F.; et al. Overweight, obesity, and postmenopausal invasive breast cancer risk: A secondary analysis of the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol 2015, 1, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglia, N.; Peano, E.; Sgandurra, P.; Moggio, G.; Pecchio, S.; Maggiorotto, F.; Sismondi, P. Body mass index (BMI) and breast cancer: impact on tumor histopathologic features, cancer subtypes and recurrence rate in pre and postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol 2013, 29, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaviani, A.; Neishaboury, M.; Mohammadzadeh, N.; Ansari-Damavandi, M.; Jamei, K. Effects of obesity on presentation of breast cancer, lymph node metastasis and patient survival: a retrospective review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013, 14, 2225–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, C.K.; Wiggins, C.L.; Nibbe, A.M.; Storlie, C.B.; Prossnitz, E.R.; Royce, M.; Lomo, L.C.; Hill, D.A. Obesity and survival among a cohort of breast cancer patients is partially mediated by tumor characteristics. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlin, T.; D'Amato, J.V.; Arendt, L.M. Obesity reversibly depletes the basal cell population and enhances mammary epithelial cell estrogen receptor alpha expression and progenitor activity. Breast Cancer Res 2017, 19, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehata, M.; Teschendorff, A.; Sharp, G.; Novcic, N.; Russell, I.A.; Avril, S.; Prater, M.; Eirew, P.; Caldas, C.; Watson, C.J.; et al. Phenotypic and functional characterisation of the luminal cell hierarchy of the mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res 2012, 14, R134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, S.M.; Haricharan, S.; Johnston, A.N.; Toneff, M.J.; Reddy, J.P.; Dong, J.; Bu, W.; Li, Y. Luminal epithelial cells within the mammary gland can produce basal cells upon oncogenic stress. Oncogene 2016, 35, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koren, S.; Reavie, L.; Couto, J.P.; De Silva, D.; Stadler, M.B.; Roloff, T.; Britschgi, A.; Eichlisberger, T.; Kohler, H.; Aina, O.; et al. PIK3CA(H1047R) induces multipotency and multi-lineage mammary tumours. Nature 2015, 525, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Keymeulen, A.; Lee, M.Y.; Ousset, M.; Brohee, S.; Rorive, S.; Giraddi, R.R.; Wuidart, A.; Bouvencourt, G.; Dubois, C.; Salmon, I.; et al. Reactivation of multipotency by oncogenic PIK3CA induces breast tumour heterogeneity. Nature 2015, 525, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendt, L.M.; McCready, J.; Keller, P.J.; Baker, D.D.; Naber, S.P.; Seewaldt, V.; Kuperwasser, C. Obesity promotes breast cancer by CCL2-mediated macrophage recruitment and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 2013, 73, 6080–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Sun, Y.L.; Ye, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, X.B.; Wang, J.M.; Wu, H.Y.; Zhang, W.J.; Yao, Y.Z. The relationship between white adipose tissue inflammation and overweight/obesity in Chinese female breast cancer: A retrospective study. Adv Ther 2020, 37, 2734–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillers, L.E.; D'Amato, J.V.; Chamberlin, T.; Paderta, G.; Arendt, L.M. Obesity-activated adipose-derived stromal cells promote breast cancer growth and invasion. Neoplasia 2018, 20, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Delgobo, M.; Agnes, J.P.; das Neves, R.N.; Falchetti, M.; Casagrande, T.; Garcia, A.P.V.; Vieira, T.C.; Somensi, N.; Bruxel, M.A.; et al. COX-2 promotes mammary adipose tissue inflammation, local estrogen biosynthesis, and carcinogenesis in high-sugar/fat diet treated mice. Cancer Lett 2021, 502, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Acrylamide; Lyon, France, 1994; Vol. 60, pp. 565.

- Rifai, L.; Saleh, F.A. A review on acrylamide in food: Occurrence, toxicity, and mitigation strategies. Int J Toxicol 2020, 39, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, M.; Levin, C.E. Review of methods for the reduction of dietary content and toxicity of acrylamide. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 6113–6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordain, L.; Eaton, S.B.; Sebastian, A.; Mann, N.; Lindeberg, S.; Watkins, B.A.; O'Keefe, J.H.; Brand-Miller, J. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 81, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Acrylamide. https://www.fda.gov/food/process-contaminants-food/acrylamide. Accessed 04/28/2024.

- Commission Recommendation (EU) 2019/1888 of 7 November 2019 on the monitoring of the presence of acrylamide in certain foods. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a8e890dc-045b-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1/language-en. Accessed on 04/28/202.

- Lee, H.W.; Pyo, S. Acrylamide induces adipocyte differentiation and obesity in mice. Chem Biol Interact 2019, 298, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.M.; Baek, J.M.; Lim, S.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Choi, I.; Cho, K.H. Modified lipoproteins by acrylamide showed more atherogenic properties and exposure of acrylamide induces acute hyperlipidemia and fatty liver changes in zebrafish. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2015, 15, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumner, S.C.; Fennell, T.R.; Moore, T.A.; Chanas, B.; Gonzalez, F.; Ghanayem, B.I. Role of cytochrome P450 2E1 in the metabolism of acrylamide and acrylonitrile in mice. Chem Res Toxicol 1999, 12, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennell, T.R.; Friedman, M.A. Comparison of acrylamide metabolism in humans and rodents. Adv Exp Med Biol 2005, 561, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Tungeln, L.S.; Churchwell, M.I.; Doerge, D.R.; Shaddock, J.G.; McGarrity, L.J.; Heflich, R.H.; Gamboa da Costa, G.; Marques, M.M.; Beland, F.A. DNA adduct formation and induction of micronuclei and mutations in B6C3F1/Tk mice treated neonatally with acrylamide or glycidamide. Int J Cancer 2009, 124, 2006–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Tungeln, L.S.; Doerge, D.R.; Gamboa da Costa, G.; Matilde Marques, M.; Witt, W.M.; Koturbash, I.; Pogribny, I.P.; Beland, F.A. Tumorigenicity of acrylamide and its metabolite glycidamide in the neonatal mouse bioassay. Int J Cancer 2012, 131, 2008–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.H.; Olsen, A.K.; Søderlund, E.J.; Brunborg, G. In vitro investigations of glycidamide-induced DNA lesions in mouse male germ cells and in mouse and human lymphocytes. Mutat Res 2010, 696, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beland, F.A.; Olson, G.R.; Mendoza, M.C.; Marques, M.M.; Doerge, D.R. Carcinogenicity of glycidamide in B6C3F1 mice and F344/N rats from a two-year drinking water exposure. Food Chem Toxicol 2015, 86, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Jumah, M.N.; Al-Huqail, A.A.; Abdelnaeim, N.; Kamel, M.; Fouda, M.M.A.; Abulmeaty, M.M.A.; Saadeldin, I.M.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Potential protective effects of Spirulina platensis on liver, kidney, and brain acrylamide toxicity in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021, 28, 26653–26663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Abo El-Ela, F.I.; Alshahrani, F.K.; Bin-Jumah, M.; Al-Zharani, M.; Almutairi, B.; Alyousif, M.S.; Bungau, S.; Aleya, L.; Alkahtani, S. Protective effects of thymoquinone against acrylamide-induced liver, kidney and brain oxidative damage in rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020, 27, 37709–37717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengul, E.; Gelen, V.; Yildirim, S.; Tekin, S.; Dag, Y. The effects of selenium in acrylamide-induced nephrotoxicity in rats: Roles of oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and DNA damage. Biol Trace Elem Res 2021, 199, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farag, O.M.; Abd-Elsalam, R.M.; Ogaly, H.A.; Ali, S.E.; El Badawy, S.A.; Alsherbiny, M.A.; Li, C.G.; Ahmed, K.A. Metabolomic profiling and neuroprotective effects of purslane seeds extract against acrylamide toxicity in rat's brain. Neurochem Res 2021, 46, 819–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acaroz, U.; Ince, S.; Arslan-Acaroz, D.; Gurler, Z.; Kucukkurt, I.; Demirel, H.H.; Arslan, H.O.; Varol, N.; Zhu, K. The ameliorative effects of boron against acrylamide-induced oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and metabolic changes in rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2018, 118, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.X.; Yue, W.B.; Ren, Y.S.; Zhang, C.X. Enhanced fat consumption potentiates acrylamide-induced oxidative stress in epididymis and epididymal sperm and effect spermatogenesis in mice. Toxicol Mech Methods 2010, 20, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adani, G.; Filippini, T.; Wise, L.A.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Blaha, L.; Vinceti, M. Dietary intake of acrylamide and risk of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2020, 29, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, P.T.; Olsen, A.; Frandsen, H.; Frederiksen, K.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A. Acrylamide exposure and incidence of breast cancer among postmenopausal women in the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study. Int J Cancer 2008, 122, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogervorst, J.G.; Baars, B.J.; Schouten, L.J.; Konings, E.J.; Goldbohm, R.A.; van den Brandt, P.A. The carcinogenicity of dietary acrylamide intake: a comparative discussion of epidemiological and experimental animal research. Crit Rev Toxicol 2010, 40, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, G.S.; Hogervorst, J.G.; Schouten, L.J.; Konings, E.J.; Goldbohm, R.A.; van den Brandt, P.A. Dietary acrylamide intake and estrogen and progesterone receptor-defined postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010, 122, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers, S.L.; Wiles, M.V.; Dunn, S.L.; Taft, R.A. Mouse estrous cycle identification tool and images. PLoS One 2012, 7, e35538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beland, F.A.; Mellick, P.W.; Olson, G.R.; Mendoza, M.C.; Marques, M.M.; Doerge, D.R. Carcinogenicity of acrylamide in B6C3F(1) mice and F344/N rats from a 2-year drinking water exposure. Food Chem Toxicol 2013, 51, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranford, T.L.; Velázquez, K.T.; Enos, R.T.; Sougiannis, A.T.; Bader, J.E.; Carson, M.S.; Bellone, R.R.; Chatzistamou, I.; Nagarkatti, M.; Murphy, E.A. Effects of high fat diet-induced obesity on mammary tumorigenesis in the PyMT/MMTV murine model. Cancer Biol Ther 2019, 20, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Delgobo, M.; Agnes, J.P.; das Neves, R.N.; Falchetti, M.; Casagrande, T.; Garcia, A.P.V.; Vieira, T.C.; Somensi, N.; Bruxel, M.A.; et al. COX-2 promotes mammary adipose tissue inflammation, local estrogen biosynthesis, and carcinogenesis in high-sugar/fat diet treated mice. Cancer Lett 2021, 502, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanos, T.; Rojo, L.; Echeverria, P.; Brisken, C. ER and PR signaling nodes during mammary gland development. Breast Cancer Res 2012, 14, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery, M.G.; Fisher, J.M.; Chien, J.Y.; Kharasch, E.D.; Dellinger, E.P.; Kowdley, K.V.; Thummel, K.E. CYP2E1 activity before and after weight loss in morbidly obese subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatol 2003, 38, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerge, D.R.; Gamboa da Costa, G.; McDaniel, L.P.; Churchwell, M.I.; Twaddle, N.C.; Beland, F.A. DNA adducts derived from administration of acrylamide and glycidamide to mice and rats. Mutat Res 2005, 580, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetsch, A.R.; Boulton, S.J.; Luscombe, N.M. Genomic landscape of oxidative DNA damage and repair reveals regioselective protection from mutagenesis. Genome Biol 2018, 19, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Grollman, A.P.; Shibutani, S. Comparison of the mutagenic properties of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyadenosine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2'-deoxyguanosine DNA lesions in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis 1999, 20, 2287–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norbury, C.J.; Zhivotovsky, B. DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2797–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia-Olvera, A.C.; Morán, J.; Camacho-Carranza, R.; Prospéro-García, O.; Espinosa-Aguirre, J.J. CYP2E1 induction leads to oxidative stress and cytotoxicity in glutathione-depleted cerebellar granule neurons. Toxicol In Vitro 2014, 28, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wu, S.; Sun, X.; Yin, R.; Ouyang, Z.; Yin, H.; Wei, Y. Amelioration of ethanol-induced oxidative stress and alcoholic liver disease by. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 3906–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grün, F.; Blumberg, B. Endocrine disrupters as obesogens. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2009, 304, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.L.; Lin, L.Y.; Chen, P.C.; Su, T.C.; Lin, C.Y. Negative association between acrylamide exposure and body composition in adults: NHANES, 2003-2004. Nutr Diabetes 2017, 7, e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Guan, T.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y. Relationship between gestational acrylamide exposure and offspring’s growth: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Public Health Nutrition 2020, 23, 1791–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Zhuang, P.; Jiao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Association of acrylamide hemoglobin biomarkers with obesity, abdominal obesity and overweight in general US population: NHANES 2003-2006. Sci Total Environ 2018, 631-632, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerge, D.R.; Young, J.F.; McDaniel, L.P.; Twaddle, N.C.; Churchwell, M.I. Toxicokinetics of acrylamide and glycidamide in B6C3F1 mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005, 202, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadry, A.M.; Friedman, M.A.; Abdel-Rahman, M.S. Pharmacokinetics of acrylamide after oral administration in male rats. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 1999, 7, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doerge, D.R.; Young, J.F.; McDaniel, L.P.; Twaddle, N.C.; Churchwell, M.I. Toxicokinetics of acrylamide and glycidamide in Fischer 344 rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2005, 208, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawi, S.M.; Marie, M.-A.S.; Fahmy, S.R.; El-Abied, S.A. Hazardous effects of acrylamide on immature male and female rats. African J Pharm Pharmacol 2012, 6, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Lin, Y.; Xue, C.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, J.; Lou, A.; Zeng, M.; He, Z.; Shen, Q.; Chen, J. Metabolic perturbations and health impact from exposure to a combination of multiple harmful Maillard reaction products on Sprague-Dawley rats. Food Funct 2022, 13, 5515–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbel, I.; Elwej, A.; Chaabene, M.; Boudawara, O.; Marrakchi, R.; Jamoussi, K.; Boudawara, T.S.; Zeghal, N. Effects of acrylamide graded doses on metallothioneins I and II induction and DNA fragmentation: Bochemical and histomorphological changes in the liver of adult rats. Toxicol Ind Health 2017, 33, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Heart Disease and Stroke. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/heart-disease-stroke.htm. Accessed 04/28/2024.

- Nichols, G.A.; Hillier, T.A.; Brown, J.B. Normal fasting plasma glucose and risk of type 2 diabetes diagnosis. Am J Med 2008, 121, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besaratinia, A.; Pfeifer, G.P. DNA adduction and mutagenic properties of acrylamide. Mutat Res 2005, 580, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanayem, B.I.; McDaniel, L.P.; Churchwell, M.I.; Twaddle, N.C.; Snyder, R.; Fennell, T.R.; Doerge, D.R. Role of CYP2E1 in the epoxidation of acrylamide to glycidamide and formation of DNA and hemoglobin adducts. Toxicol Sci 2005, 88, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manière, I.; Godard, T.; Doerge, D.R.; Churchwell, M.I.; Guffroy, M.; Laurentie, M.; Poul, J.M. DNA damage and DNA adduct formation in rat tissues following oral administration of acrylamide. Mutat Res 2005, 580, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Oliveira, N.G.; Pingarilho, M.; Gamboa da Costa, G.; Martins, V.; Marques, M.M.; Beland, F.A.; Churchwell, M.I.; Doerge, D.R.; Rueff, J.; et al. Cytogenetic damage induced by acrylamide and glycidamide in mammalian cells: correlation with specific glycidamide-DNA adducts. Toxicol Sci 2007, 95, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, Z.N.; Calgan, D.; Ozakat, E.; Varnali, T. Acrylamide and glycidamide adducts of Guanine. J Mol Structure: THEOCHEM: 2005; Vol. 728, pp 249-251.

- Patel, A.A.; Zhang, Y.; Fullerton, J.N.; Boelen, L.; Rongvaux, A.; Maini, A.A.; Bigley, V.; Flavell, R.A.; Gilroy, D.W.; Asquith, B.; et al. The fate and lifespan of human monocyte subsets in steady state and systemic inflammation. J Exp Med 2017, 214, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölzl-Armstrong, L.; Kucab, J.E.; Moody, S.; Zwart, E.P.; Loutkotová, L.; Duffy, V.; Luijten, M.; Gamboa da Costa, G.; Stratton, M.R.; Phillips, D.H.; et al. Mutagenicity of acrylamide and glycidamide in human TP53 knock-in (Hupki) mouse embryo fibroblasts. Arch Toxicol 2020, 94, 4173–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhivagui, M.; Ng, A.W.T.; Ardin, M.; Churchwell, M.I.; Pandey, M.; Renard, C.; Villar, S.; Cahais, V.; Robitaille, A.; Bouaoun, L.; et al. Experimental and pan-cancer genome analyses reveal widespread contribution of acrylamide exposure to carcinogenesis in humans. Genome Res 2019, 29, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marković Filipović, J.; Miler, M.; Kojić, D.; Karan, J.; Ivelja, I.; Čukuranović Kokoris, J.; Matavulj, M. Effect of acrylamide treatment on Cyp2e1 expression and redox status in rat hepatocytes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, N.; Nguyen, L.V.; Makarem, M.; Dong, Y.; Shih, K.; Eirew, P.; Raouf, A.; Emerman, J.T.; Eaves, C.J. Glutathione-dependent and -independent oxidative stress-control mechanisms distinguish normal human mammary epithelial cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 7789–7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.S.; Long, T.Y.; Chiang, S.Y.; Wu, K.Y. Characterization of primary glutathione conjugates with acrylamide and glycidamide: Toxicokinetic studies in Sprague Dawley rats treated with acrylamide. Chem Biol Interact 2021, 350, 109701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennell, T.R.; Sumner, S.C.; Snyder, R.W.; Burgess, J.; Spicer, R.; Bridson, W.E.; Friedman, M.A. Metabolism and hemoglobin adduct formation of acrylamide in humans. Toxicol Sci 2005, 85, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, F.C.; Dip, R.; Naegeli, H. Expression profile of human cells in culture exposed to glycidamide, a reactive metabolite of the heat-induced food carcinogen acrylamide. Toxicology 2007, 240, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, F.J. Role of cytochromes P450 in chemical toxicity and oxidative stress: studies with CYP2E1. Mutat Res 2005, 569, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, A.A.; Cederbaum, A.I. Oxidative stress, toxicology, and pharmacology of CYP2E1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2004, 44, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjumäki, R.; Pridgeon, C.S.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. CYP2E1 in alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver injury. Roles of ROS, reactive intermediates and lipid overload. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Symptoms & Causes of NAFLD & NASH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/nafld-nash/symptoms-causes. Accessed 04/28/2024.

- Orellana, M.; Rodrigo, R.; Varela, N.; Araya, J.; Poniachik, J.; Csendes, A.; Smok, G.; Videla, L.A. Relationship between in vivo chlorzoxazone hydroxylation, hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 content and liver injury in obese non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Hepatol Res 2006, 34, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, N.M.; Quiñones, L.A.; Orellana, M.; Poniachik, J.; Csendes, A.; Smok, G.; Rodrigo, R.; Cáceres, D.D.; Videla, L.A. Study of cytochrome P450 2E1 and its allele variants in liver injury of nondiabetic, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis obese women. Biol Res 2008, 41, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, K.; French, S.W.; Morgan, T.R. Production of a cytochrome P450 2E1 transgenic mouse and initial evaluation of alcoholic liver damage. Hepatology 2002, 36, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butura, A.; Nilsson, K.; Morgan, K.; Morgan, T.R.; French, S.W.; Johansson, I.; Schuppe-Koistinen, I.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M. The impact of CYP2E1 on the development of alcoholic liver disease as studied in a transgenic mouse model. J Hepatol 2009, 50, 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, T.; Kumar, N.; Perriotte-Olson, C.; Casey, C.A.; Donohue, T.M.; Harris, E.N.; Talmon, G.; Kabanov, A.V.; Saraswathi, V. Nanoformulated SOD1 ameliorates the combined NASH and alcohol-associated liver disease partly via regulating CYP2E1 expression in adipose tissue and liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2020, 318, G428–G438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minato, T.; Tsutsumi, M.; Tsuchishima, M.; Hayashi, N.; Saito, T.; Matsue, Y.; Toshikuni, N.; Arisawa, T.; George, J. Binge alcohol consumption aggravates oxidative stress and promotes pathogenesis of NASH from obesity-induced simple steatosis. Mol Med 2014, 20, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmiel-Haggai, M.; Cederbaum, A.I.; Nieto, N. Binge ethanol exposure increases liver injury in obese rats. Gastroenterology 2003, 125, 1818–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Maza, M.P.; Hirsch, S.; Petermann, M.; Suazo, M.; Ugarte, G.; Bunout, D. Changes in microsomal activity in alcoholism and obesity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000, 24, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarver, D.G.; Byun, R.; Hines, R.N.; Hichme, M.; Wegenek, W. A genetic polymorphism in the regulatory sequences of human CYP2E1: association with increased chlorzoxazone hydroxylation in the presence of obesity and ethanol intake. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1998, 152, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).